Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 129

February 6, 2013

The lesson of Petraeus for other generals?

I've

said before the lessons I think other

generals will draw incorrectly

from the fall of David Petraeus. His real mistake, I think, was going directly

from four-star command to the directorship of the CIA. Rather, he should have

taken some time out and reoriented himself. So the real lesson, I think, is

that the time of retirement from high position is a vulnerable moment.

I didn't

think much of Dick Cheney as a vice president, but I think he was a good

defense secretary. I remember being told that when he left that job, he got in

a car and drove across the country alone. Another thing to do might be to go

camping or sailing for a few weeks. The point is to get out of the bubble,

re-connect to the world, and most of all, catch your breath.

Being a Quaker missionary for peace in Fayetteville, N.C., is like...

Well, let's just say

it looks like a tough gig.

February 5, 2013

Question of the day: Was removing Saddam Hussein in fact a good thing?

Recently I was at a foreign policy discussion in which a

participant said that everybody agrees that the removal of Saddam Hussein was a

good thing, despite everything else that went wrong with the boneheaded

invasion of Iraq.

I didn't question that assertion at the time, but found

myself mulling it. Recently I had a chance to have a beer

with Toby Dodge, one of the best strategic thinkers

about Iraq. He said something like this: Well, you used to have an oppressive

dictator who at least was a bulwark against Iranian power expanding westward.

Now you have an increasingly authoritarian and abusive leader of Iraq who

appears to be enabling Iranian arms transfers to Syria.

And remember: We still don't know how this ends yet. Hence

rumors in the Middle East along the lines that all along we planned to create a

"Sunnistan" out of western Iraq, Syria, and Jordan.

Meanwhile, the Iraq war, which we left just over a year ago,

continues. Someone bombed police headquarters in Kirkuk over the weekend, killing 33. And

about 60 Awakening fighters getting their paychecks were blown up in Taji. As my friend Anthony Shadid used to

say, "The mud is getting wetter."

What Max Boot missed: A response about the future shape of the U.S. military

By Billy Birdzell

Best Defense guest respondent

I believe Max

has missed Das Boot.

1. If COIN is 80 percent political, then the political

construct is most important. French and British in Algeria and Malaya were

conquerors with political and military control over the place for 124 years

(ironic) before their insurgencies began. Please talk about expeditionary COIN.

Russia in Afghanistan, U.S. Afghanistan, U.S. Vietnam, U.S. Iraq. Where else? The

United States in the Philippines 1898-1913 was the Malaya example because we

owned the place. Mixing up political contexts = fail.

2. No matter how good our tactics, cultural training,

language ability, etc., we will never get out of the dilemma that the harder we

try, the worse it gets. More money for AID and development = more corruption. More

troops = accidental guerrillas and al Qaeda in Iraq type organizations. Joe Meyers

and UBL call it defensive jihad, but whatever. Our very presence delegitimizes

the government we are trying to prop up. It's a failed model and one that

Galula said was the worst of all possible worlds. FM 3-24 is a manual for the

worst case scenario -- that in which the military gets stuck with an

insurgency that it didn't see coming. It can, at best, direct military

force to get a slightly better political situation than running away. It is not

a doctrine around which to structure the military.

3. I disagree that language, culture, etc. materially impact

success. Using the military instead of the State Department for diplomacy is

inherently flawed. The military's main contribution is destroying armed groups

who challenge the government's monopoly on force and I'd like to see what

percentage of intelligence was developed by native speakers/culture experts.

4. Tanks are fabulous for killing guerrillas in urban areas.

Artillery is your friend and outbound rounds still make the sound of freedom. Flying

machines are cool. Max fundamentally does not understand that COIN involves

high intensity combat and our technology/firepower, USED APPROPRIATELY, gives

us an edge.

5. I agree with Nagl that advisors a la Landsdale during Huk

(20 PAX, later increased to 56), El Sal (55 PAX), JSOTF-P, and Columbia

are great. However, like all other uses of military force, what is the

strategy? What is the United States trying to achieve? What are we going to

give up to do more/longer/better engagements with which partner nation forces? We

can have the best advisors in the world, if the partner nations do not have

real governments and a military with the will to fight, we're pissing in the

wind.

6. The most important factors for success against irregulars

-- partner nation governance and the local military's will -- are out of our

hands. Those two issues are not discussed by people who want to rearrange the

military and create all kinds of nonsense. If eliminating safe havens and

supporting stable governments is our policy, then what kind of military

deployments maximize the host nation's ability to create legitimacy and find

their will to win? I argue that Max's

concepts minimize them.

Billy Birdzell

served eight years in the Marine Corps, was a platoon commander during OIF I

and II and a team leader in

MARSOC

. He

is now

doing that Security Studies thing at Georgetown University.

FDR as a strategic analyst of the Balkans

I was

reading Robert Sherwood's Roosevelt

and Hopkins,

and was struck that in March 1943, President Roosevelt made a prescient

observation about the future of Yugoslavia. Harry Hopkins, his close aide,

quotes him as saying in a meeting with Anthony Eden that, "the Croats and Serbs

had nothing in common and that it is ridiculous to try to force two such

antagonistic people to live together under one government."

February 4, 2013

Hagel before Senate Armed Services: A confirmation hearing or a mugging?

I just

finished reading the transcript of last week's hearing on the confirmation of

former Sen. Charles Hagel to be defense secretary. The question in the headline

is what I asked myself as I read it.

I heard

a lot on Friday about what a poor job Sen.

Hagel did in his confirmation hearings to be secretary of defense. So I sat

down with the transcript over the weekend. I was surprised. I've spent many hours

covering confirmation hearings, but I never have seen as much bullying as there

was in this hearing. The opening thug was Sen. Inhofe (which I expected -- he's

always struck me as mean-spirited), but I was surprised to see other Republican

senators kicking their former Republican colleague in the shins so hard.

Here's

John McCain badgering his erstwhile buddy:

Senator MCCAIN. ...Even as late as August

29th, 2011, in an interview -- 2011, in an interview with the Financial Times, you said, "I disagreed

with President Obama, his decision to surge in Iraq as I did with President

Bush on the surge in Iraq." Do you stand by those comments, Senator Hagel?

Senator HAGEL. Well, Senator, I stand by

them because I made them.

Senator MCCAIN. Were you right? Were you

correct in your assessment?

Senator HAGEL. Well, I would defer to the

judgment of history to support that out.

Senator MCCAIN. The committee deserves your

judgment as to whether you were right or wrong about the surge.

Senator HAGEL. I will explain why I made

those comments.

Senator MCCAIN. I want to know if you were

right or wrong. That is a direct question. I expect a direct answer.

Senator HAGEL. The surge assisted in the objective.

But if we review the record a little bit--

Senator MCCAIN. Will you please answer the

question? Were you correct or incorrect when you said that "The surge would be

the most dangerous foreign policy blunder in this country since Vietnam." Where

you correct or incorrect, yes or no?

Senator HAGEL. My reference to the surge

being the most dangerous--

Senator MCCAIN. Are you going to answer the

question, Senator Hagel? The question is, were you right or wrong? That is a

pretty straightforward question. I would like an answer whether you were right

or wrong, and then you are free to elaborate.

Senator HAGEL. Well, I am not going to give

you a yes or no answer on a lot of things today.

Senator MCCAIN. Well, let the record show

that you refuse to answer that question. Now, please go ahead.

Senator HAGEL. Well, if you would like me

to explain why--

Senator MCCAIN. Well, I actually would like

an answer, yes or no.

Senator HAGEL. Well, I am not going to give

you a yes or no. I think it is far more complicated that, as I have already

said.

Tom

again: FWIW, Hagel later got in the point that his comment was that "our war in

Iraq was the most fundamental bad, dangerous decision since Vietnam." I think

that assessment is correct.

(Senator

Chambliss then took a moment to abuse the English language: "We were always

able to dialogue, and it never impacted our friendship.")

Then

Lindsay Graham waded in.

Senator GRAHAM. ...You said, "The

Jewish lobby intimidates a lot of people up here. I am not an Israeli senator.

I am a U.S. Senator. This pressure makes us do dumb things at times." You have

said the Jewish lobby should not have been -- that term shouldn't have been

used. It should have been some other term. Name one person, in your opinion,

who is intimidated by the Israeli lobby in the U.S. Senate.

Senator HAGEL. Well, first--

Senator GRAHAM. Name one.

Senator HAGEL. I don't know.

Senator GRAHAM. Well, why would you say it?

Senator HAGEL. I didn't have in mind a

specific--

Senator GRAHAM. First, do you agree it is a

provocative statement? That I can't think of a more provocative thing to say

about the relationship between the United States and Israel and the Senate or

the Congress than what you said.

Name one dumb thing we have been goaded into

doing because of the pressure from the Israeli or Jewish lobby.

Senator HAGEL. I have already stated that I

regret the terminology I used.

Senator GRAHAM. But you said back then it

makes us do dumb things. You can't name one Senator intimidated. Now give me

one example of the dumb things that we are pressured to do up here.

Senator HAGEL. We were talking in that

interview about the Middle East, about positions, about Israel. That is what I

was referring to.

Senator GRAHAM. So give me an example of where

we have been intimidated by the Israeli/Jewish lobby to do something dumb

regarding the Mideast, Israel, or anywhere else.

Senator HAGEL. Well, I can't give you an

example.

Next to

throw some punches was David Vitter:

Senator VITTER. In general, at that time

under the Clinton administration, do you think that they were going ‘‘way too

far toward Israel in the Middle East peace process"?

Senator HAGEL. No, I don't, because I was

very supportive of what the President did at the end of his term in

December-January, December 2000, January of 2001. As a matter of fact, I

recount that episode in my book, when I was in Israel.

Senator VITTER. Just to clarify, that's the

sort of flip-flop I'm talking about, because that's what you said then and you're

changing your mind now.

Senator HAGEL. Senator, that's not a

flip-flop. I don't recall everything I've said in the last 20 years or 25

years. if I could go back and change some of it, I would. But that still

doesn't discount the support that I've always given Israel and continue to give

Israel.

Near the end of the day's verbal beating,

Senator Manchin said, "Sir, I feel like I want to apologize for some of the tone

and demeanor today." That was good of him.

You all know I was not that much of a Hagel fan before. But now I feel more inclined to

support him, if only to take a stand against the incivility shown by Senators Inhofe,

McCain, Graham, and Vitter, the SASC's own "gang of four."

'American Sniper' author shot dead

I don't know what to say about this murder of the Navy SEAL sniper, committed by a former

Marine at a Texas gun range. I do think our culture is sick with guns.

Avast! What Tom should have been reading about the age of fighting sail

By

Jeff Williams

Age

of fighting sail bureau

"C. S. Forester" (AKA Cecil

Louis Troughton Smith) was a delightful writer of fiction but a less successful writer of naval history. His Age of Fighting Sail has long received mixed reviews among modern naval

historians interested in that period. Forester had a tendency towards "received

wisdom" and was careful not to contradict technical details he had already

incorporated into his marvelously successful "Hornblower" series novels.

As we all know,

there is a tendency for nations to inflate their victories and diminish their

defeats. Consequently, it had become customary in re-telling the extraordinary

saga of the British Navy in the age of sail to emphasize the superiority of

French-built ships versus those of the Royal Navy. It made the long period of

English naval victories even more amazing and intrepid. Even still, like most

myths, the lore of superior French and Spanish ship design did in fact contain

an element of truth for a period.

In the past thirty

to forty years a great deal of intense academic research has been performed

concerning the ship building and construction practices of the French, Dutch,

Spanish, and American sailing navies, but most particularly into the British

Navy of the sailing era. Much legend (knee deep when it comes to

naval affairs) has been stripped away by contemporary naval historians

such as Brian Lavery, Robert Gardiner, and others.

Brian Lavery is undoubtedly the world's leading authority on the sailing ships of

the line, having spent decades researching the subject to its smallest detail. He

has a number of volumes to his credit but the ones that directly address the

subject of this article would be:

The

Ship of the Line -- The Development of the Battlefleet 1650 -1850, Vol. One

The Ship of

the Line -- Design, Construction & Fittings, Vol. Two

Nelson's

Navy, The Ships, Men and Organization 1793-1815

In Building

The Wooden Walls -- The Design and Building of the 74-Gun Ship Valiant, Lavery uses his

first two chapters to describe how the Royal Navy entered the 18th century

undefeated but with ships that were generally poorly designed. Their design

patterns had become rigidly conservative with little scope for experimentation.

This was partly due to a complacency derived from long success in battle. Why

fix what's not broken?

The French on the

other hand, understanding that they could not defeat the British Navy because

of the need to finance large standing armies and a shortage of ports and seamen,

decided on a policy of building speedier and more powerful ships. Later in the

century, the new American Navy facing the same problems as the French adopted a

similar policy in lieu of a battle fleet.

For the British

the end of that complacency came in 1755 with a new surveyor of the Navy, the

redoubtable Sir Thomas Slade, and his partner William Bately. The creative

logjam in the hidebound surveyors office, that controlled the design protocols

for the Navy, was removed and British shipbuilding moved into a new era.

At the time of the

Seven Years War, the Royal Navy as a result of the through defeat of both the

French and Spanish in battle had captured many of the latest French and Spanish

ships. As standard practice, the Navy took the lines off those ships, repaired

them if possible and incorporated them into its own fleet. With the practical

experience of having these captured ships now as part of the British fleet it

became apparent that they contained many advantageous qualities. Slade merged

many of those French ideas with his own into a new British building practice.

As an example, it

was customary in that era for French battleships to be more "weatherly"

(meaning how close they can sail to the wind) by being able to sail 6 points (on

the 32 point compass rose) to the wind, while the average British battleship

could usually manage only 7 points. That weatherliness was usually largely a

function of the relationship between the length and breadth of a vessel. That

feature was very important for ships trying to achieve the "weather gauge" (upwind)

on an enemy vessel -- rather like a Spitfire fighter trying to gain an altitude

advantage on a ME 109.

Slade's new

renaissance in British naval construction is usually considered to have been

initiated with the building of HMS Valiant.

This ship's lines were actually taken from the captured French Invincible. Valiant,

along with her sister Triumph, were

the lead ships in a new 74-gun class that began to standardize the British

battle line for the next 70 years. British ships were lengthened, their

armament re-ordered to be more formidable, and the ships became nearly as fast

and weatherly as their French peers but more robustly built.

It should be noted

that while French ships were fast and Weatherly, there was a price to pay for

those features. One of the costs was "hogging," a circumstance where the bow

and stern of the ship actually droops down from a lack longitudinal strength,

thus destroying its sailing qualities over time. Generally, British shipwrights

tried to keep the scantlings and timbers stouter than French practice and also

maintained narrower room and space (the space between frames) than the French

in order to minimize the hogging of the keel. Later, British dockyards used the

Sepping's method that allowed a greater length to be built into their ships by

using a very strong diagonal framing process. Also, in the new class of ships,

the British lower main gun decks were designed to be a little higher above the

waterline in order to make them less wet and more available when the ship

heeled in the wind. Often the lower gun decks of French ships were so low to

the water that even in a moderate breeze the gun ports were unusable.

Importantly, I

might add that the British were the first to completely copper the bottoms of

their entire fleet beginning around the time of the American War for Independence.

This factor had a radical impact upon hull durability and speed, comparable

with almost any changes in actual ship design. It was hugely expensive but kept

ships out of dry-dock and improved their weatherliness and speed and helped

assist uniform the speed characteristics of the whole battle fleet when in

formation. This crucial change in itself was comparable in impact to the 20th

century's incorporation of the microprocessor into modern naval electronics.

In consequence of

these changes, the battles fought by the British Navy from the period of the

American Revolution, French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic wars were

generally fought with ships of equal or superior design characteristics to

those of their assorted opponents. This was particularly true of British

frigate designs that evolved even faster and were the blue water cruisers of

their era.

As most people who

have an interest in naval history know, ship design was only one factor -- important

as it was in the development of naval superiority. Unlike armies, navies cannot

be improvised. They required factors such as the availability of trained and

experienced seamen, gunnery science, navigation skills (advanced mathematics),

seamanship, signaling (an area of complete British superiority), and a

developed and practiced doctrine of aggressive leadership. These were all

crucial in achieving and maintaining superiority at sea. As the superlative

American Admiral Nimitz said, "better good men on a bad ship than bad men on a

good ship."

As a final note,

Spanish ships (many British considered Spanish captures superior to those of

the French) and Dutch ships to a lesser extent were also very interesting in

their own right and deserve coverage. The Dutch naval tradition is outstanding

though their ships had a tendency to be rather small and shallow of draft to

allow them to clear the mud flats off the Dutch coast. The American

contribution to naval design in the age of sail was both unique and of

generally very high quality and is a full story in itself.

Incidentally, Robert Gardiner, a superb historian of naval architecture, has a number of books out on the specific

design elements of various classes of ships such as frigates, brigs, ships of the line, etc., of this period. His work is excellent and

spares no detail.

February 1, 2013

How a rogue pilot misbehaved for years in a B-52 squadron, and so killed 4 people

Of all

the military services, the one I know least about is the Air Force, which

doesn't get a lot of electrons on this blog. So I was especially intrigued to

finally sit down and go through a study sent to me months ago by a Best Defense

reader. "Darker Shades of Blue: A Case Study of

Failed Leadership"

is a thorough, careful study of how leadership lapses over the course of

several years ultimately led to disaster in an Air Force bomber wing. It's also

a beautiful if horrifying exploration of how bad shit can happen despite

volumes of rules and regulations aimed at ensuring safe practices are followed.

Even if

you care nothing about the Air Force, it is a fascinating study of leadership,

and applicable to many different situations. Basically, it is the tale of how

an out-of-control pilot managed to consistently break the rules, but did so

with a clever understanding of how to manipulate the system. So, for example,

he would push the limits until his commander sat him down and gave him an oral

warning. But these were not recorded. So the pilot, who had a reputation as

perhaps the best B-52 pilot in the Air Force, would lay low a bit and then,

when the next commander came in, the pattern would repeat itself. The rogue

pilot got by on a series of these "last chance" reprimands. Subordinates knew

what was going on, and found themselves in the position of either risking their

lives by flying with him, or risking their careers by refusing to do so.

When a

senior officer was told about video evidence showing a recent instance of

flight indiscipline by the free-styling pilot, he responded, "Okay, I don't

want to know anything about that."

Eventually,

on June 24, 1994, a B-52 with the rogue pilot at the controls went down at Fairchild

Air Force Base while attempting a tight 360 degree left turn around the control

tower at 250 feet above the ground. It "banked past 90 degrees, stalled,

clipped a power line with the left wing and crashed," killing four crew members

-- three lieutenant colonels and a colonel.

The key

thing to watch, warns the author, Tony Kern, is "incongruity between senior

leadership words and actions." That is a very important lesson for any

organization.

(A big tip of the official BD baseball

cap to the person who sent me the link a couple of months ago -- I searched all

four of my e-mail accounts and couldn't find who it was, but I appreciate it.)

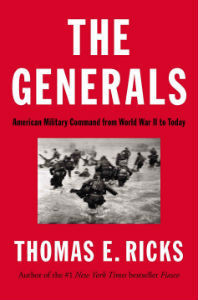

From Stars & Stripes and NPR's 'Talk of the Nation': The latest news on my book

Here's a nice review of my new book from Stars & Stripes. (Sorry, Hunter.)

They get to the point quickly: "The idea that

people who aren't good at their jobs must be fired shouldn't be a revolutionary

concept in a place like the Army, where failure gets people killed." The bottom

line: "Army leaders would do well to take notes."

I also was on NPR's Talk

of the Nation earlier this week with two novelists whose

work I admire, Karl Marlantes and Tim O'Brien. They are both Vietnam vets. It

was a moving show. I teared up during one of the phone calls.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers