Mike Duran's Blog, page 16

May 5, 2016

Amish Romance Recovery Network Helps Fiction Readers Cope with 21st Century

“It started like most addictions,” Nancy (last name withheld) admitted. “Only, in this case, the pusher was my local Christian bookstore.”

“It started like most addictions,” Nancy (last name withheld) admitted. “Only, in this case, the pusher was my local Christian bookstore.”

Apparently, looking for “escapist” reads can be dangerous in today’s world. Especially if you’re an evangelical Christian. For Nancy, escaping into the world of Amish fiction became an escape from reality. “At first,” she said, “the stories about tight-knit communities where families sat around the dinner table without the distractions of television and cell phones, became a respite from my hectic schedule.” Soon, however, she found herself reading nothing but Amish fiction. “Men named Malachi and Lemuel became my Fabio. Instead of throwing a scantily clad female over their shoulder, it was a bale of hay. My Amish addiction was like mommy porn, only without the porn.”

Many have sought to explain the Amish romance craze among evangelical readers. Even with the trend recently slowing, it is estimated that Amish fiction comprises up to one-third of all Christian novels. Acquisitions editor Phil Short suggested that the going motto of Christian publishers has become, “When all else fails, put a bonnet on it.” While Short admits that the trend is an odd match for an audience typically picky about theological content, he conceded that in Christian publishing circles doctrinal integrity is often massaged by the bottom line. “It’s easy to justify catering to odd fictional trends when your house also publishes Bibles.”

According to religious sociologist Zola Smart, the factors that have bolstered the Amish trend among evangelical readers are the rise of hypermodernity, hypersexualization, and biblical illiteracy. “Culture’s hectic pace, the increase of incivility and sexual immorality, and the glut of technologies have propelled many spiritually weary readers to escape into novels about a simpler, purer way of life.” Compound this with a reactionary view of culture, a superstitious approach to holiness, and terrible hermeneutics, Smart concludes, “The exponential growth of Amish fiction among Evangelicals during the first decade of the twenty-first century cannot be understood apart from these ‘hyper’ cultural developments and Fundamentalist views of holiness.”

“I fell hard for Amish fiction,” Nancy acknowledged. “The twenty-first century seemed to be becoming less and less real to me. I would find myself daydreaming about a world without zippers, laptops, and profanity. But I was living in a fantasy world.” It was this realization that caused Nancy to admit she had a problem. “I was having withdrawals,” she confessed. “I couldn’t drive past my local Christian bookstore without thinking of young bearded Christian men in overalls.”

At first, Nancy was ostracized by her reading partners. Just the suggestion that Amish Romance could be an addiction which perpetuated a false caricature of the real world led to accusations of ‘worldliness.’ “They questioned my faith,” she said tearfully. “They insinuated that I was watching PG-13 movies and possibly even having wine with my dinner. It was painful.” But the heartbreak gave way to hope as Nancy eventually formed her own group for similar addicts. “Truth is, the devil doesn’t always appear with horns and sulfur. Sometimes he disguises himself with a straw hat, overalls, and rock hard abs.” While she does not recommend going cold turkey, Nancy admits that sometimes it’s necessary to simply avoid the ‘Christian Romance’ section altogether.

Now the Amish Romance Recovery Network exists to help other addicts, like Nancy. “You’re never ‘recovered,’” she said. “But always ‘recovering.’” And as for her goals? “One day I hope to visit a Barnes & Noble. Eventually, Lord willing, I might read a Military Suspense, Science Fiction, or maybe even a Classic.”

May 2, 2016

Are the Dead Aware of the Living?

At that moment, I knew — although the word know seemed so feeble in describing the certainty I felt — that everything Ellie had said was true. My father had seen it too, this land just beyond the great river. I was here because of them. And others.

Surrounded now by a great cloud of witnesses.

A single tear coursed my cheek. In later days, I would describe it as a baptism of sorts. That tear, washing me of my unbelief.

— Excerpt from The Ghost Box, Chapter 25

The Ghost Box is not Christian fiction. But there’s lots of Easter eggs for the faithful. One is found in the scene above. In it, an important character dies and Reagan Moon, my snarky hero, with the help of some peculiar old goggles, is able to watch that character’s soul actually leave their body, bound across a “golden river,” and begin a sojourn into a new, glorious estate. The experience is a turning point for my spiritually skeptical protag.

In the novel, I use a phrase that’s lifted straight out of Scripture. Here’s the verse it was taken from:

Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles. And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us (Heb. 12:1 NIV)

So Reagan Moon realizes that his own life is a “race,” that others have gone on before him, and that he is “surrounded by… a great cloud of witnesses.” In the previous chapter (Heb. 11), the biblical writer listed the long succession of saints and martyrs that have preceded us — Abel, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Sarah, Moses, Joshua, Rahab, Samson, etc., etc. Hebrews 11 is often called the “Hall of Faith” because of the vast array of “witnesses” it describes. The imagery is that of a coliseum filled with the faithful departed, a “great cloud of witnesses” who are looking down upon us, urging us forward.

Question: Is this imaginary or actual? Are the saints of the past actually looking down upon us, witnessing our travails, cheering us on, or is this simply a metaphor used to encourage us to “follow in their footsteps,” so to speak?

I tend to see this, and similar biblical images, as literal. That somehow, in some fashion, the holy dead are aware of the living. No, I can’t confidently say that this is a “proof text” for such a position. Nor do I think there IS a definitive one. Nevertheless, I don’t think the Scripture definitively states that the dead have no knowledge of the realm of the living. In fact, I believe just the opposite.

I realize this is an uncomfortable position for many evangelicals. We have this penchant for demystification. Unexplained phenomenon is best cordoned off behind cautionary Scriptures. It’s why ghosts, for example, are typically viewed as demons in evangelical circles. The notion that a disembodied soul can impinge upon and/or interact with our dimension is unsettling. If not flat-out heretical. Of course, the Bible is clear in forbidding necromancy, consultation with the dead, and the seeking out of occult seers and mediums. That’s indisputable. Nevertheless, there are several biblical occurrences that lend some credence to the idea that deceased saints are aware of the living.

The “spirit” of Samuel — The most famous and perhaps the most puzzling “ghost incident” in Scripture is Saul and the Witch of Endor (I Samuel 28). When Saul compels a seer to summon the prophet Samuel, they witness “a spirit coming up out of the ground” (vs. 13). The spirit is recognized as the dead prophet who seemingly validates himself by prophesying against Saul and predicting the king’s death in battle (vss. 16-19). Not only does the encounter suggest that the holy dead exist in close proximity to earth, but that they are conscious, and aware of a timeline of events, both past and (possibly) future.

The Mount of Transfiguration — In Mark 9:2-8, two dead prophets—Moses and Elijah—manifest alongside Jesus. Scripture is unclear as to their state, being that they appear neither ghosts nor resurrected bodies. Complicating matters is the fact the prophets “were talking with Jesus” (vs. 4), interacting within an earthly timeline and a physical estate.

The Rich Man and Lazarus — Because this is a parable, we must be careful not to force too much literalism into the tale. Nevertheless, in Luke 16:19-21, Jesus tells the story of a rich man who dies and is sent to Hades “where he was in torment” (vs. 23). From this state, the rich man appeals to Father Abraham to “send Lazarus to my family, for I have five brothers. Let him warn them, so that they will not also come to this place of torment” (vss. 27-28). If we assume Jesus is illustrating a real condition in the afterlife, then the deceased rich man remains conscious after death, aware of his five brothers, and requests they be reached in “real time.”

The souls under the altar of God — The Book of Revelation offers up a remarkable glimpse of heaven, in particular after the opening of the fifth seal of wrath the apostle John sees “under the altar the souls of those who had been slain because of the word of God and the testimony they had maintained. They called out in a loud voice, ‘How long, Sovereign Lord, holy and true, until you judge the inhabitants of the earth and avenge our blood?'” (Rev. 6:9-10) Again, some may object on the grounds that Revelation is largely metaphorical. Even so, we are given a picture of souls who are at rest, conscious, quite aware of a timeline of earthly events and awaiting the culmination of their avenging.

These verses aren’t enough to make a slam dunk case that a real cloud of deceased witnesses is really aware of us and cheering us on toward the finish line. Conversely, I’m not sure there’s an airtight case against such a point of view either. In fact, some faith traditions view the “Communion of the Saints” as not simply a metaphorical fellowship, but a vibrant reality.

In his book, For All Saints: Remembering the Christian Departed, N.T. Wright says this:

By the end of the fourth century some believed that the presence of the martyrs’ relics in their midst conveyed what one writer has called ‘the veritable and gracious presence of the martyrs themselves, and through them of the Godhead with Whom they were united.’ The church on earth believed itself privileged to enjoy an intimate fellowship with those who had gone on ahead. Hilary and Augustine, in the fourth and fifth centuries, both elaborated this doctrine. The angels and saints, the apostles, prophets and patriarchs, they argued, surrounded the church on earth and watched over it. Christians here are to be conscious of their communion with the redeemed in heaven, who have already experienced the fullness of the glory of Christ. this, or something like it, is the doctrine which we affirm when we say ‘the Communion of the Saints’ towards the end of the Apostles’ Creed. (For All Saints: Remembering the Christian Departed, N.T. Wright, pg. 16)

Of course, this view can give rise to beliefs such as prayers for the dead and even purgatorial indulgences. But in the broader sense, All Saints Day and the Communion of the Saints is built off of a clear biblical idea that

Deceased saints are conscious after death

Deceased saints are at rest

Deceased saints are in fellowship with God

Deceased saints have some awareness of the living and the present

Those who ‘die in the Lord’ enjoy fellowship — both present and future — with the saints

While there is no biblical precedent for praying to departed saints, the recognition that we are “privileged to enjoy an intimate fellowship with those who [have] gone on ahead” and should “be conscious of [our] communion with the redeemed in heaven” is rooted in Scripture and church history. So I suppose the bigger question isn’t whether the dead are aware of the living, but what forms our “intimate fellowship” and “communion with” the “great crowd of witnesses” should take.

April 27, 2016

When is Fictional Magic Promoting the ‘Occult’?

The rods of Moses and the Magicians turned into Serpents

A while back, I received this letter from a pastor who follows my blog. At the time, he was unfamiliar with the debates inside Christian writing circles concerning speculative fiction, the use of tropes containing magic, and the characteristics of Christian fiction in general. That changed when he entered the ministry:

I am a brand spanking new pastor, and I am already engaged in a divisive discussion with one of my congregants about fiction, particularly the use of “supernaturalism” in fiction. For example, this person believes that when Aslan uses “magic” or does things “supernaturally” like breathing on Mr. Tumnus, and does NOT give glory and honor and credit to Jesus Christ IN THE STORY, that it is occultism, since his power is derived from elsewhere than from the one true God. I think this is a bit, shall I say, crazy. I was just wondering if you have encountered such thought elsewhere, or am I the only one so uniquely blessed!!! And what would you say about the claim that any “powers” that occur in a fictional novel, especially Christian novels, are subtly promoting occultism. Thanks for your work.

This pastor may find solace in the fact that not only is he NOT alone in this debate, but that the position assumed by this congregant is, sadly, all too common among Christian readers.

As much as I’d like to offer a definitive answer to this question — How can we know when “‘powers’ that occur in a fictional novel… are subtly promoting occultism”? — I don’t think there is one. In fact, the more we demand a definitive answer, the more we create (inadvertently?) a “magical” scoring system to sanitize our fiction for “discerning” readers.

Before I proceed, let me back up and clarify. The reason I placed the word discerning in quotations above is not because I advocate for ignorance. The Scripture is clear about our need to “test the spirits” (I Jn. 4:1), “test everything” (I Thess. 5:21), and “have [our] senses trained to discern good and evil” (Heb. 5:14). Because of this, I applaud the congregant above who asks the question. At least they are taking such biblical charges to heart. In fact, it could be said that the reader / cultural consumer who never asks hard questions about their literary and visual diet could find themselves worse off than the individual they decry as puritan. So in this sense, taking seriously the commands to be critical and discerning of what we put into our mind is healthy.

Nevertheless, there’s a couple problems with the approach and/or conclusion reached by this discerning congregant.

For one, many “Christian” things — not just fantastical stories — can be twisted to “promote the occult.” A good example could be the story of the bronze serpent in Numbers 21:6-9. A plague of serpents was sent among the rebellious Israelites. God provided a way of escape from this punishment by commanding Moses to build a bronze serpent on a pole. Whoever looked upon this image would be saved. However, years after this incident we learn that the bronze serpent was being worshiped and in a series of reformations, King Hezekiah destroyed it.

He removed the high places and broke the pillars and cut down the Asherah. And he broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had made offerings to it (it was called Nehushtan). 2 Kings 18:4

This story illustrates what is all too common among our fallen species — we worship what we shouldn’t. In many cases, even good things, sacred things, or simply neutral objects, can be deified. Whether its religious icons like crosses or statues, people whom God has used, or even systems and rituals, just about anything can be vested with a “power” never intended. Point is, fictional magical powers aren’t the only things that can be used for occult purposes.

In fact, that approach itself can become a type of superstition. Let me explain this by asking a question: Does attributing a supernatural incident to God or the devil actually change its power source? Or to use the example above, if Aslan had stopped and given glory to God, would that have turned his magic from “bad” to “good”? If so, what made the supernaturalism bad in the first place?

To follow this line of reasoning, the real “occultism” resides not in the supernatural event (Aslan breathing upon Mr. Tumnus and bringing the faun back to life), but in the author’s defining of it. Or more clearly, NOT defining it. Thus, to the more conservative Christian reader, the greatest potential “evil” for a Christian writer is to depict ambiguous magic, i.e., supernatural power not directly attributed to God.

Which makes fiction, “magic.”

However, this creates huge problems for authors, the least of which is feeling bound to clarify the source of every character’s supernatural action. Spells, miracles, alchemy, and enchantment are only tolerable in Christian fiction as long as we’re clear where they are coming from. However, this type of approach not only potentially strips our stories of mystery and nuance, we treat our readers like auditors who’ll be combing our novels for pesky heretical gnats.

The point here is to highlight how our approach to fiction can often be as problematic as the stories themselves. The congregant above who worried over Aslan’s apparent lack of Divine attribution is emblematic of a breed of religious reader who approaches fiction with a rather rigid doctrinal lens. Am I suggesting that we should put down our “theological” guard when we read and be less discerning? Absolutely not. But we need to see fiction as doing something different than simply illustrating and reinforcing Bible doctrine.

Truth is, if Aslan had explained that the power came from Jesus Christ he would have been lying. Why? Because Jesus never breathed on the faun. You see, fauns aren’t even real. And neither is Aslan. So how can we say Jesus breathed life into Tumnus the Faun? Such a charge carries its own sort of blasphemy in assuming that a fictional character can be attributed with the actual power of Jesus.

(To be fair, some have pointed out the difference between allegory and fantasy fiction. The Christian claiming her story as allegory is more bound to theological rigor as it is intended to parallel some existing doctrinal truth. This is the grounds upon some object to The Shack. So this may or may not apply depending upon one’s view of Narnia, its mode of fictional transport, and how far one is willing to turn Tumnus from a fictional faun into an allegorical archetype.)

Such discussions can quickly become an exercise in endless hair-splitting. So let me return to my basic point: In their attempt to maintain theological integrity, many have embraced superstition, a “touch not, taste not” mentality (Col. 2:21) that purports a magic all its own. In other words, we believe there is magic in biblical (?) formulas. As if God was bound by incantations, recipes, rituals, and our personal holiness program.

How is this any different from sorcery?

Yes, Scripture is clear that there can be false prophets and false miracles. The world of occultism, we are warned, is not a plaything. Nevertheless, the Bible is not always clear in defining the source of real magic or the trappings for conjuring it.

Take the case of Moses’ encounter with the Pharaoh’s magicians (Ex. 7). Both sides produced, more or less, the same “magic,” turning staffs into snakes. Question: Is it wrong to turn staffs into snakes? Answer: It can’t be because Moses did it! So the problem wasn’t necessarily with the “magic” (i.e., staff charming), but with the intent, motivations, and allegiances of those who wielded it.

The similar distinction is made in the apostles’ encounter with Simon the Sorcerer (Acts 8:9-25). Simon “had practiced sorcery in the city and amazed all the people of Samaria” (vs. 9) with his magic, so much so that he was called “the Great Power of God” (vs. 10). But after Simon “believed and was baptized” (vs. 13), he coveted the power of the Holy Spirit and asked to pay for it (vs. 19). Notice carefully Peter’s response:

Peter answered: “May your money perish with you, because you thought you could buy the gift of God with money! You have no part or share in this ministry, because your heart is not right before God. Repent of this wickedness and pray to the Lord in the hope that he may forgive you for having such a thought in your heart. For I see that you are full of bitterness and captive to sin.” (Acts 8:20-23 NIV)

Interestingly enough, throughout this record Simon’s power is never attributed to Satan. However, he is upbraided “because [his] heart is not right before God.” So what was Simon’s sin? Apparently sorcery wasn’t the big one; his magic was less at issue than his sinful heart.

A case could be made, I think, that supernatural powers (and their fictional depictions) aren’t bad in themselves (see staff charming). It is the hearts and motives of the handlers that is evil. Not all staff charmers are wicked. Which means staff charming is up for debate.

The concerned congregant above (and the “anti-magic” crowd in general), go astray when they focus on forms of magic (levitation, incantations, objects, staff charming, breathing upon petrified fauns, etc.), more than the purveyors. It is far easier to make an external checklist — You know your character’s supernatural powers are NOT occult when you _________ (fill in the blank with preferred magic you avoid or attribution you render) — than to allow internal assessment and potential ambiguity.

Either way, no amount of attribution can prevent some readers from misinterpreting you. Heck, even the Bible is misinterpreted to say things it doesn’t. So why should our stories be any different? The truth is, readers can potentially mistake anything I write about as endorsing something I don’t.

April 18, 2016

Top 5 Clichés Christians Use About Their Writing

This past weekend I was privileged to be part of the faculty for the Orange County Christian Writers Conference (OCCWC) 2016. I had a great time and met lots of cool people. Writers are odd enough, Christian writers even more so. You see, Christian writers have their own cluster of cliches and secret ciphers known only to “initiates.” Not only do we often speak in “Christianese” about our writing, but we’re always dragging God into the biz. Of course, I’m not suggesting that Christian writers leave God on the stoop when they write or market. The problem is when we over-spiritualize the craft and use God as a scapegoat for procrastination, unprofessionalism, and even lack of sales. Like the person who believes God’s “given” them a story and “called” them to write (#5), but are treating that “God-given” story and God-breathed “calling” as if it was optional. Like Moses at the burning bush they find excuse after excuse for either a.) shining or b.) doing a crappy job on what Heaven has laid hold upon them to do. You know, because of the kids, their job, their health, their school — whatever — they just can’t follow through. They say they’re “waiting on God” for the “right timing” but they’re really just waiting on God to sit down at the keyboard and write the darned book for them. Listen, if God’s really “called you to write,” He wants YOU to learn the craft and make the time to do it, and do it well. Maybe you should stop “waiting on Him” and put your hand to the plow. Anyway, that’s just one example of the unique, sometimes screwy approach that Christian novelists bring to their craft.

This past weekend I was privileged to be part of the faculty for the Orange County Christian Writers Conference (OCCWC) 2016. I had a great time and met lots of cool people. Writers are odd enough, Christian writers even more so. You see, Christian writers have their own cluster of cliches and secret ciphers known only to “initiates.” Not only do we often speak in “Christianese” about our writing, but we’re always dragging God into the biz. Of course, I’m not suggesting that Christian writers leave God on the stoop when they write or market. The problem is when we over-spiritualize the craft and use God as a scapegoat for procrastination, unprofessionalism, and even lack of sales. Like the person who believes God’s “given” them a story and “called” them to write (#5), but are treating that “God-given” story and God-breathed “calling” as if it was optional. Like Moses at the burning bush they find excuse after excuse for either a.) shining or b.) doing a crappy job on what Heaven has laid hold upon them to do. You know, because of the kids, their job, their health, their school — whatever — they just can’t follow through. They say they’re “waiting on God” for the “right timing” but they’re really just waiting on God to sit down at the keyboard and write the darned book for them. Listen, if God’s really “called you to write,” He wants YOU to learn the craft and make the time to do it, and do it well. Maybe you should stop “waiting on Him” and put your hand to the plow. Anyway, that’s just one example of the unique, sometimes screwy approach that Christian novelists bring to their craft.

And there’s more where that came from.

This last weekend reminded me of the many ways we Christians attempt to hijack God, “baptize” our writing with the “spiritual” seal of approval, and conveniently justify mediocrity. Having frequented Christian writing circles for some time now, I’ve heard all the spiritualized slogans we believers like to regurgitate. So here’s my Top 5 clichés that Christians use about their writing.

5.) “God’s called me to write.” — It’s funny how God never “calls” Christians to be plumbers, landscapers, nursery workers, ad agents, or write obituaries for the local newspaper. After all, being “called to write” sounds way more spiritual than being “called to clean toilets.” And then there’s the issue of discerning a genuine “calling” from your own inclinations or dreams. I mean, couldn’t your “call from God” really just be a desire to see your name on a book cover, in a bookstore? Or maybe you’re just wired to write in the same way a chef is wired to cook — it’s not so much a divine summons as it is in your DNA.

4.) “It just wasn’t God’s will that I… (fill in the blank).” — “God’s will” is a favorite “out” for Christian writers. Most often, the saying is followed by things like “find an agent,” “sell a lot of books,” “get published by a traditional press,” “finish the manuscript,” or “advertise aggressively.” Authors love to leverage this against “God’s called me to write,” as in, “God called me to write the book, but I guess it wasn’t His will that I sell very many.” Poor God. I wish He’d get His act together so your career can finally flourish.

3.) “Marketing is not my spiritual gift.” — Then you might reconsider #5. Unless God’s also “gifted” you with spare change to hire publicists and marketing strategists, it’s best to assume that if God wants you to write novels, He also wants you to find readers. It’s amazing how many Christian writers feel called to the mountaintop to hear from God only to justify leaving the sacred tablets unread. Perhaps the “call to write” also comes with a “call to market.” Hearing from God means getting the docs into people’s hands. It doesn’t require a spiritual gift, just effort. Funny how hard work can make up for the absence of “spiritual gifts.”

2.) “I want to glorify God in my writing.” — Usually this is code for “clean,” alternative, G-rated fare containing redemptive resolutions, biblical references, salvation events, spiritual themes, or subliminal Bible messages imbedded in the story. The question I have is whether God is also “glorified” in a good, well-crafted story. If we can only “glorify God” by specifically writing about God, quoting Scripture, making sure our characters don’t curse and, if they do, get saved by the end of the tale, we reduce God-honoring lit to simply religious tracts. If a Christian writer can only glorify God by writing about explicitly “Christian” stuff, then freelancers, sports reporters, obit writers, corporate copywriters, trade magazine columnists, and even game coders had better find some other way to “glorify God,” because they can’t do it in their writing.

1.) “I write for an audience of One.” — Sounds great. But unless He’s also giving you direct revelations, critiquing your novels, correcting your grammar, dialog, characterization, and plot elements, and buying your books, all this means is that you never have to answer to anyone but yourself.

So there you have it! A quintet of cop-outs. My advice to Christian writers: Maybe it’s time we stop over-spiritualizing our craft, hanging the blame on God, and just start digging in.

April 15, 2016

Christianity’s Internal and External Witness

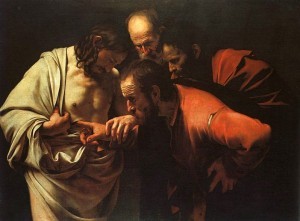

Public Domain, Caravaggio – The Incredulity of Saint Thomas

Christianity, unlike the Eastern religions I was weaned on as a young adult, appeals to and requires both physical and historical evidence — archaeological discoveries, geographical locations and recorded customs, real figures and events, written history, laws and instruction — as well as heart change, spiritual transformation, and personal revolution. The balance between those two — Internal and External witness — is incredibly important to the validity and uniqueness of the Christian faith.

As a spiritual seeker in the late 70’s, it was Eastern religion’s lack of historical, external, rational grounding that inevitably left me unsatisfied. In his book, Autobiography of a Yogi, when Paramahansa Yogananda speaks of things like gurus levitating or transporting, it inspires but rings somewhat hollow. Why? There just isn’t enough actual evidence for it. Whereas, in the case of the Resurrection of Christ for example (the central claim of Christian testimony), there were over five hundred witnesses (I Cor. 15), many of whom would go on to be martyred, substantive documentation of the names and events in question, as well as references to verifiable customs, locations, and figures. Furthermore, the alleged event propelled a ragtag group of followers without political or financial clout to explode onto the historical scene and quickly become one of the world’s great religions, influencing human history in more ways, perhaps, than any other.

Pursuing enlightenment (or detachment) — a central tenet of many Eastern religions — is an entirely subjective experience. As a spiritual seeker in the late 70’s, tail-end of the 60’s counter-cultural shifts, most of my religious / spiritual experiences had been subjective. It was research into the authenticity and reliability of the Bible which rocked my world. I quickly discovered that there was more to Christianity than just a bunch of outlandish claims made in a dusty old document. There was objective evidences! Of course, this didn’t make Christianity infallible and absolutely compelling. I mean, many people look at the evidence and reject the claims of Christ and Scripture. However, it was Christianity’s emphasis upon subjective and objective evidences that made it both open to criticism and, ultimately for me, satisfying.

I’ve since come to believe that Christianity, unlike other world religions, presents a significant, compelling balance between objective and subjective witness, reason and intuition, proofs and faith. Or to put it another way, Christianity appeals to both meta-narratives and micro-narratives—meta-narrative being a grand, all-encompassing story, theory, or point, micro-narrative being a personal, individual story that may or may not buttress the bigger point. However, those external evidences (biblical meta-narrative) didn’t mean much until I had an internal experience, change of heart, revelation (personal micro-narrative).

Some (perhaps most) religions rely heavily on internal evidence for their validation. I personally know quite a few Mormons. If you ask a Mormon how they know Mormonism is true, they will often mention a “burning in the bosom” experience. This internal witness is incredibly important to the average Mormon’s testimony. While evangelical Christians consider Mormonism heterodox, Christians often (I think mistakenly) approach their faith in a similar way. They will say, “I believe Christianity is true because I know it in my heart, I’ve changed, and God has spoken to me.” Of course, God may indeed have spoken to them! But how is this any different from the Mormon, the Hindu, or the Unitarian Universalist who makes a similar claim? The problem is obvious: Any beliefs can be justified if they don’t require external validation.

On the other hand are religions that rely too heavily on external evidence, tradition, or custom. There is no revelation required, just compliance; a shell of ritual devoid of transformation. Yet when you ask for validation, persuasion is lacking. So an angel spoke to Mohammed or Joseph Smith. So Buddah was enlightened. So the Maharishi spoke to an ascended master a long, long time ago. So the fundamentalist cult leader claims he is receiving direct messages from God. The question is how are these claims to authority and revelation tested? How is Mohammed’s credibility as a prophet tested, Buddah’s status as an enlightened master validated, or Christ’s claim to deity verified?

Of course, this does not mean that the objective, historical evidences for Christianity persuades everyone and can’t be challenged. As Pascal suggested, God provides us with enough evidence to believe, but not so much that we don’t need faith. Once again, it’s a balance between the internal and external. And this is one thing I find uniquely compelling about Christianity: It respects the fact that I am both a physical and a spiritual being, my head and my heart need engaged. Jesus Christ actually lived, performed miracles, and rose from the dead. But he still requires my faith and says I must be born again.

We are in danger whenever we lose this balance and emphasize the subjective, experiential elements of Christianity over the objective, rational elements of Christianity. Or vice-versa. A religion that is built entirely upon a historical event but lacks transformative power is flawed and inevitably bound to lifeless tradition. Conversely, a religion that is entirely about enlightenment without any grounding in reason or external evidences, is not worth believing.

April 4, 2016

Why You Should Consider Registering for Realm Makers 2016

Last year, I attended Realm Makers for the first time. In fact, I was privileged to teach two electives there. There’s a bit of a story behind our intersection. While my first two novels were published in the CBA (Christian Booksellers Association), I have for years vocally expressed concern about the lack of representation of the spec genre in Christian publishing circles. This goes WAY back. For example, in 2010 I asked Why ‘Supernatural Fiction’ is Under-Represented in Christian Bookstores and also conducted a Speculative Fiction Panel in which I queried about the state of the spec genre in Christian publishing and why, with the genre’s prolific representation in mainstream culture, it was so poorly repped in Christian circles. After attending the ACFW (American Christian Fiction Writers) conference in Dallas in 2012 (that was my third or fourth writers conference), part of my “debriefing” included these thoughts:

Christian publishers have absolutely no idea what to do with speculative fiction. Or YA. Both are a very thin slice of the industry pie and often a marketing headache. A couple examples. Randy Ingermanson was one of the first authors to write speculative Christian fiction (some novels over a decade ago). He admitted he was planning to edit the books and re-introduce them into the general market. Why? Because spec-fic doesn’t sell well in the CBA. Another example: During the agent panel I attended, the question arose about YA lit and the agents’ response was sort of meh. In fact, Rachelle [my agent] mentioned that one of her teenage daughter’s all-time favorite series was Lisa Bergren’s River of Time (the first which won the 2012 Christy Award for best YA) which was later dropped by Cook… before the series ended. Her daughter was heartbroken. Bergren has since self-published the remainder of the series through CreateSpace. It’s a sad reminder of how orphaned those who write genres other than Romance or Historicals really are.

Issues had been brewing for some time between mainstream CBA / ACFW loyalists and writers of speculative fiction who continued to feel like misfits trapped in a parallel world of Romance and Amish fangirls. Even the Christy Awards, the premiere literary awards for Christian fiction, dropped their speculative fiction category saying that there simply were not enough entries. The Christys later re-introduced a “Visionary” Category which encompassed all the speculative fiction subgenres. This did not soften the continued sense that speculative fiction was an odd fit in contemporary Christian publishing circles.

In 2012, after attending the ACFW conference in Dallas, things appeared to come to a head. After a brief run-in between the spec cosplay crowd and the ACFW staff (which you can dig around elsewhere for), “the board [was] set, the pieces [were] moving,” to quote a famous wizard. Of course, I did the curmudgeonly thing and challenged spec writers to get more serious. I suggested Maybe It’s Time We Hung Up the Ol’ Spock Ears, and my ears were roundly boxed. Sort of. Anyway, here’s what I wrote:

It’s bad enough that Christian publishers are unsure what to do with speculative fiction writers. But must we compound this by acting like outsiders?

The first ever Christian writers conference I attended back in 2006 had a workshop for speculative fiction writers. Frankly, I was a little embarrassed to be in it. Why? Not only did it seem a tad cliquish and groupie-ish, next to the cerebral, visionary sci-fi and fantasy writers I’d come to love, these folks seemed liked goofballs.

And it didn’t help that some of them were wearing costumes.

Yes, I know that conventions and conferences draw out the nerds. And there’s nothing wrong with wearing a toga or brandishing a foam sword to the banquet. If dressing up like C3PO and rolling out the British accent is your thing, go for it. Also, I realize that spec writers dwell in a sort of perpetual Neverland, seeing the world through a unique prism of imagination that Historical Romance authors would run, shrieking from, with petticoat girded appropriately. Yeah, I get all that.

But being that Christian speculative fiction writers already seem out of place in the industry, it doesn’t help our cause to act so… out of place.

This kind of give-and-take, along with the angsty noodling of people who enjoy dressing up like elves and robots, finally gave way to something that had been in the works for a while. Realm Makers held its first ever conference in 2013. Including staff, roughly 90 participants attended. Pretty good for a first-time effort. The two years following has continued to see significant numerical growth (I believe that last year attendance was in the 150 range). Logging this kind of progressive growth is an important indicator of the health, vision, and relevance of a fledgling organization like RM.

According to their vision statement, Realm Makers exists,

To provide a faith-friendly symposium for writers and artists, focused on science fiction, fantasy, and all their sub-genres. Whether participating artists wish to gear their content for the inspirational or mainstream marketplace, they have a place at Realm Makers.

So while the tenuous history between spec authors and the CBA / ACFW may play a part, RM is less a reaction against and more a response to a much larger vision. What Christian spec authors have been saying for the longest — that speculative fiction is a powerful and popular genre for readers and writers across the faith spectrum — is the power source behind the RM steamship. While it is acknowledged that mainstream Christian fiction is a viable genre, with many fine authors, serving a valid purpose, we also wish to acknowledge the vast, under-represented lovers of faith and speculative fiction who often feel displaced by the consensus demographic of mainstream publishing.

Possibly the best reason I can give for considering to choose to attend Realm Makers 2016 is that developing relationships with other writers who have similar faith and fiction passions is incredibly important. Look, I am not a big conference person, I lean more to introvert than extrovert, don’t do cosplay, can be socially awkward, and take stress meds. (Wow. This makes me sound like a head case!) I taught two electives at last years’ conference. It was my first time in attendance. I was nervous. I sweat a lot. Yes, it helped that I knew so many people from online interaction. But that also contributed to the nerves. Nevertheless, by far my biggest takeaway was meeting and interacting with so many cool people. Yes, being yoked by our penchant for the weird played a part. It’s a big relief to be able to mention Miskatonic University or a Rancor without being looked at like a loon. However, the sense of camaraderie and curiosity and friendliness is what lingered. Sure, this is probably the same spiel given by many conference reps. However, I found it to be hugely important. I know many writers are like me — not a big people person, prefer to stay home and read or write, somewhat socially awkward. But let me encourage you — Not only are writerly relationships important, but you may have more to offer to someone else than you think. So first I’d suggest that developing relationships with other writers who have similar faith and fiction passions is a huge thing.

Which leads to a second reason I’d suggest you consider registering for RM2016 — Developing long-term industry connections is huge to your writing career. At this stage, RM is “small” enough to provide access to many talented and influential people. Last year, I rubbed shoulders with Robert Liparulo, Tosca Lee, Steve Laube, Kirk DouPonce, Dave Long, and others. These kinds of relationships can prove incredibly valuable to a long-term writing career. (No, I’m not elevating Ben Wolf to celebrity status quite yet.) Perhaps my biggest surprise was when Donita Paul said that she’d read my blog. Gulp! There’s plenty of attendees who will not fit the “celebrity” bill (sorry Ben), but can be valuable travelers along the journey (I hope this doesn’t come off as me suggesting to we “use” people to climb the ladder of success, cause I’m not.) Aspiring cover artists, great editors who are just now forging a career, future beta readers and online critique partners, even indie press publishers will all be relatively accessible during the conference. In fact, one of the neat things about RM (and one reason they’re able to keep their prices low) is because they utilize university campus facilities and dorms (this years’ is Villanova). Because most attendees bunk in the dorms, it allows for lots of after hours discussions (something I’ll be doing more of this year). All that to say, RM is a great place to meet industry folks and develop relationships with like-minded authors and editors that could prove valuable to a long-term career.

Finally, let me go out on a limb and say that the reason RM has shown continued growth over the last three years is because it has identified a genuine niche. Christian artists have long embraced the speculative genres. Whether it was George MacDonald’s fairy tales, Tolkein’s epic fantasy, or C.S. Lewis’ space trilogy, believers have often seen the spec genres as a powerful tool of apologetic and inspirational storytelling. Which is one of the reasons why spec’s under-representation in the Christian market is so troubling. You can find plenty of conferences on speculative fiction — DragonCon, ComicCon, etc., etc. However, conferences that seek to integrate issues of faith, a biblical worldview, and theology with sci-fi, fantasy, and horror, are virtually non-existent. At the expense of sounding like an infomercial, RM may be tapping into an important growing trend in Christian art — equipping and populating mainstream culture with “Christian” voices, ideas, representatives, and stories of the speculative, fantastical genre.

Anyway, there’s a few reasons why I think you should consider attending Realm Makers 2016. Yes, I’ll be teaching there again. (You can see my class descriptions HERE.) Yes, I’ll definitely be bringing my stress meds and appearing socially awkward. And, no, I won’t be dressing up like Robin Hood. (However, I may wear my Marvel socks.) Nevertheless, I’m looking forward to meeting new friends, seeing “old” ones, and encouraging a new breed of author to blaze new trails. You can register HERE.

March 30, 2016

I Like Big ‘Buts’ — An Evangelical Counter-Argument to Sex & Nudity in Cinema (Pt. Three)

I’ve divided the common evangelical arguments against watching sex and nudity in film into these four:

I’ve divided the common evangelical arguments against watching sex and nudity in film into these four:

“Would you let your mother, spouse, or child do that?” — The Golden Rule argument

“But the images on the screen are REAL.” — The Nudity Isn’t Fake argument

“Seeing naked people on screen causes people to sin.” — The Seeing is Sin argument

“Nudity is not required to make the story better.” — The Cleaner the Better argument

In my last post in this series, I concentrated on the Golden Rule argument. In this post, let’s focus on the second:

II.) The Nudity Isn’t Fake argument — “But the images on the screen are REAL.”

Gregory Shane Morris in his recent article No Buts About It juxtaposed onscreen nudity against onscreen violence:

Here’s how this one goes: Baby-boomers raised their kids with violence in their breakfast cereal. They let us watch “Tom and Jerry” and play “Halo” and “Call of Duty,” took us to see “The Passion of the Christ,” and taught us to vote for George W. Bush. Moral majoritarian parents have raised a generation of children bathed in blood and gore. But they clutch their pearls every time a nipple slips out onscreen. “How is that consistent?” some ask.

I usually pose a counter-question: How many people has director Michael Bay—the sultan of cinematic pyrotechnics—actually blown up? How many victims’ lives did Alfred Hitchcock claim? Now, how many women have actually stripped in front of cameras for nude scenes?

John Piper makes the crucial point that media sexuality, by its very nature, is real in a way that media violence is not. Death and dismemberment in Hollywood are accomplished through prosthetics, makeup, rubber knives, and CGI-wizardry. By contrast, nude scenes really happen. Real actors and actresses remove real clothes from their real bodies.

While I admit there’s a case to be made against overusing or glorifying violence, the comparison with graphic nudity is apples-to-kumquats. Human nature is not programmed to react to violence in the way it is programmed—hardwired even—to react to explicit sexual imagery.

As with many of these arguments, there’s a lot of connective tissue which needs examined. Briefly, here’s three assumptions that are imported into this objection which need clarified:

An assumption that nudity is inherently shameful or sinful.

An assumption that nudity is always sexual in its expression.

An assumption that nudity is always of the same (i.e., explicit) gradation in film.

The power of the aforementioned argument — “But the images on the screen are REAL” — often assumes one of these three things, that because nudity is inherently sinful / shameful, sexual in its expression, and/or of the same gradation and not fake, therefore it is wrong to watch it onscreen. But do those assumptions hold water? For the sake of time, and being that the arguments are all inter-connected, let’s focus mainly on that first assumption.

Does the Bible teach that nudity is inherently shameful or sinful? In a recent Facebook “discussion” on this subject, one commenter said to me, “Nudity is shameful in the bible almost without exception.” Is it? This is usually the big question for if it can be shown that ALL occurrences of nudity in Scripture are seen as shameful, or that being seen nude is almost always a sin, this would be a compelling argument against watching all onscreen nudity. Some of the most common proof texts for this position are:

The shame felt by Adam and Eve after they sinned (Gen. 3:7)

The nakedness of Noah and the cursing of Canaan (Genesis 9:20-27)

General laws of sexual morality (Lev. 18)

Not exposing oneself on an altar (Ex 20:26)

Isaiah’s public nakedness as a sign of shame (Is. 47)

Covering of nakedness takes away shame, spiritually (2 Cor. 5, Rev. 5)

There are others, but these are perhaps the most oft-referenced. Several things should be noted here. First we should note that there is no explicit statement in any of these verses condemning nakedness or nudity in general. (By this I mean something along the lines of ‘Thou shalt not publicly disrobe,’ or something similar.) Yes, public nudity is often viewed as shameful and definitely not endorsed. And covering someone’s, or our own, nakedness, is seen as virtuous (Ezekiel 16:7-9). That seems pretty clear. But whereas the Bible explicitly condemns specific sexual acts (lust, adultery, incest, homosexuality,etc.) it does not explicitly condemn nakedness. For example, while some use the incident of Noah as an example that nakedness is sin, it has been debated for thousands of years exactly what the sin of Ham was. The four most common theories are incest, castration, mockery, and patriarchal disrespect. The inference that nakedness is inherently evil may be extrapolated from this incident, but this is hardly a proof text for such a position. Perhaps the most unfortunate cause of this is interpretation is that earlier versions of the Bible translated condemnation of sexual immorality in terms of nakedness. Here’s some examples from Leviticus 18, one of the most common sources of “proof texts” for this position, contrasting the KJV and the NIV.

Lev. 18:6 — None of you shall approach to any that is near of kin to him, to uncover their nakedness: I am the LORD. (KJV) / No one is to approach any close relative to have sexual relations. I am the LORD. (NIV)

Lev. 18:7 — The nakedness of thy father, or the nakedness of thy mother, shalt thou not uncover: she is thy mother; thou shalt not uncover her nakedness. (KJV) / Do not dishonor your father by having sexual relations with your mother. She is your mother; do not have relations with her. (NIV)

Lev. 18:9 — The nakedness of thy sister, the daughter of thy father, or daughter of thy mother, whether she be born at home, or born abroad, even their nakedness thou shalt not uncover. (KJV) / Do not have sexual relations with your sister, either your father’s daughter or your mother’s daughter, whether she was born in the same home or elsewhere. (NIV)

So as you can see, if we use the KJV translation “uncovering the nakedness” as reference to literal nakedness, we have a strong case. However, upon closer inspection, it’s clear that the term commonly used to condemn all nakedness as sin / shame is a euphemism for “having sexual relations.” Studying parallel commentaries on this section of Scripture is helpful, clearly revealing that the phrase is not a blanket condemnation of nudity. For example, Barnes simply defines the phrase:

To uncover their nakedness – i. e. to have sexual intercourse. The immediate object of this law was to forbid incest.

Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary goes into more details, but renders the same result:

None of you shall approach to any that is near of kin to him—Very great laxity prevailed amongst the Egyptians in their sentiments and practice about the conjugal relation, as they not only openly sanctioned marriages between brothers and sisters, but even between parents and children. Such incestuous alliances Moses wisely prohibited, and his laws form the basis upon which the marriage regulations of this and other Christian nations are chiefly founded. This verse contains a general summary of all the particular prohibitions; and the forbidden intercourse is pointed out by the phrase, “to approach to.” In the specified prohibitions that follow, all of which are included in this general summary, the prohibited familiarity is indicated by the phrases, to “uncover the nakedness” [Le 18:12-17], to “take” [Le 18:17, 18], and to “lie with” [Le 18:22, 23]. The phrase in this sixth verse, therefore, has the same identical meaning with each of the other three, and the marriages in reference to which it is used are those of consanguinity or too close affinity, amounting to incestuous connections.

My point here, again, is not to support or advocate for public nudity. I am not a Christian nudist. My point is that such “proof texts” are flimsy, at best. Misleading, at worst.

Then you have the issue of non-condemnatory (let’s call them neutral) occurrences of nudity in Scripture.

Saul, along with the Prophets of his day, went nude — “He stripped off his garments, and he too prophesied in Samuel’s presence. He lay naked all that day and all that night. This is why people say, ‘Is Saul also among the prophets?'” (1 Sam. 19:24)

David danced before the Lord wearing nothing but a ‘revealing’ linen ephod — There is considerable dispute as to whether or not David danced naked or immodestly (2 Sam. 6:14)

Isaiah went naked for 3 years as “a sign and portent” of Egypt’s captivity and shame — (Isa. 20:2,3)

The Garasene demoniac lived naked among the tombs — (Lk. 8:26-27).

Jesus was stripped naked on the cross — (Matt 27:28; Luke 10:30)

Peter appears to have been fishing naked — “Therefore that disciple whom Jesus loved saith unto Peter, ‘It is the Lord.’ Now when Simon Peter heard that it was the Lord, he girt his fisher’s coat unto him, (for he was naked,) and did cast himself into the sea” (John 21:7 KJV)

The Apostle Paul and Barnabas tear their clothing to show their humanness to the townspeople of Lystra when they thought they were the Greek gods Hermes & Zeus — (Acts 14:14) While not typically interpreted as stripping naked, some note that philosophers would, on occasion, publicly strip themselves to prove they were not immortal.

We could include in this list the ritualistic aspects of circumcision and baptism, both of which were often performed publicly, in community, as a statement of faith. Starting with Abraham, God instituted circumcision for every male, with some of this occurring during adulthood. In fact, the apostle Paul spoke openly about circumcising Timothy himself (Acts 16:3). There is also much evidence that early Christian baptisms were performed with the recipient naked. So is nudity “shameful in the bible almost without exception” as my Facebook friend said? Not exactly. And even if it is shameful, seeing it, speaking about it, or the impact it has on us (see: Isaiah’s three-year naked prophecy!) is not described as automatically defiling. These verses, of course, are not proof texts for endorsing public nudity, only possible evidence that nakedness does not carry the blanket condemnation or stigma which some conservative Evangelicals like to suggest.

Furthermore, those who use the Nudity is Sin argument will usually concede exceptions. Doctors seeing patients naked is an exception. Parents seeing their children naked is an exception. Spouses seeing each other naked is an exception. And really, the list can go on. When I go to the gym, I often see other men naked in the locker room. Is this an automatic sin — for me AND them?

The Catholic Geeks summarize it this way in their essay The Body on Screen:

If nudity were evil in itself, then a man would be guilty of wrongdoing every time he bathed or changed his clothing, and every infant born into this world would commit sin as soon as he left his mother’s womb. If nudity were evil, married couples would have no choice but to resort to evil every time they tried to fulfill God’s command to “Be fruitful and multiply.”

So, if nudity is not wrong, why does man wear clothing? He wears clothing to guard against concupiscence. Adam’s sin caused an imbalance between man’s body and soul, so that the soul no longer has the control over the bodily passions it once had. Images may arouse illicit or inappropriate passions, providing temptations. When an image (meaning something seen by the eye; not necessarily art) involves the human body, particularly when it is unclothed, it can lead to sexual temptations.

This has led many Christians to condemn nudity on the charge that it leads to sexual sins, whether physical or mental. But an universal condemnation is impossible, because the sight of the unclothed human body is not evil. The body is created by God, and everything He creates is good. Seeing the body of another is seeing something good, and that sight does not incur sin. If misused, that sight can lead to sin, but it is never sinful in itself. (emphasis mine)

This undermines the Nudity Isn’t Fake argument in this way — If nakedness is not categorically evil and seeing it is not automatically defiling, then watching real nakedness in cinema is also not categorically sin.

I will agree with conservative proponents that God has clothed us for a reason and that one of those reasons has to do with shame. When Adam and Eve sinned, they were aware of themselves and their bodies in ways God never intended. This was not, however, because their bodies had suddenly become evil, but because they had. Jesus was clear when He said, “Anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Matt. 5:28 NIV). It was not the “looking at a woman” that Jesus described as sin, it was the looking “lustfully.”

Jesus did not draw the line at nakedness. He drew it at lust.

That is important in this discussion because one of the assumptions often imported is that all cinematic nudity is designed to inspire lust. Of course, many Hollywood portrayals of nudity are indeed sensual and intended to arouse “concupiscence.” Attempting to argue for more license (whether the filmmaker’s, actor’s, or viewer’s) without acknowledging the vast amounts of improper, gratuitous nudity is conveniently short-sighted. That said, it also must be admitted that cinematic nudity is simply not all the same. The nudity in The Bible is different than the nudity in The Graduate, is different than the nudity in Schindler’s List, is different than the nudity in The Wolf of Wall Street. Yes, Morris uses the term “graphic nudity” (I’m assuming to distinguish it from partial or non-gratuitous nudity). Yet those who object to watching any onscreen nudity often take no care to distinguish between tasteful or partial nudity and “graphic nudity.” Instead, watching ALL cinematic nudity is condemned.

In order to discuss this issue honestly and fully, we simply must acknowledge that onscreen nudity comes in lots of different forms, some mild, some suggestive, some tasteful, some explicit. Broad-brushing all cinematic nudity ignores the intentions and craft of the filmmakers (which is a violation of the Golden Rule argument). One reason why such concessions are not made is that to do so would be to undermine an important plank in their argument — that all nakedness is shameful or sinful.

This argument also breaks down when its connection to art becomes dismissive. While some concede that “fake” nudity — CGI nudes, sculpted nudes, painted nudes — should be given a pass, others do not. In his article, Morris writes

…art, like anything else, can be bent to serve good or evil. Indeed, art has a particular penchant for training our minds how to think, our bodies how to behave, and our souls what to love. This is why I also object to fully CGI nude scenes with no flesh-and-blood people depicted (something already common in the gaming world). To habituate our minds to lust is to warp them.

I think Morris’ objection is more compelling than those who want to conveniently throw out “images” and “reproductions” of nudity on the grounds that this nudity is fake. Again, he writes,

We’ve conditioned ourselves to look at pixels or projections and see objects rather than people—objects that exist for our pleasure. But as many a grieving wife and divorcee can tell you, that instinct to treat people as objects rarely stays in the virtual world. It warps the way we look at those around us, and defiles the secret and sacred bed of marriage where God meant us to enjoy nudity.

And here we agree: If nakedness is categorically shameful then ANY reproduction of it invokes, appeals to and potentially conjures REAL images and impulses.

In his post Nudity in Film, Joshua Gibbs unpacks this forced disconnect between fake nudity and real nudity:

So far as the actors working on sets are concerned, Russell Crow didn’t actually die at the end of Gladiator (to be carried off and eulogized by Ridley Scott), although Kirsten Dunst is actually nude for about half a second on the set of Marie Antoinette(a fact attested to by Coppola’s camera). However, while Dunst was actually nude on the set of Marie Antoinette, we don’t see the actual living Kirsten Dunst actually nude when we watch the film. Rather, we see an image of Dunst nude— an image in exactly the same way that American realist painter Andrew Wyeth created images of Helga Testorf nude, or Titian created images of Mary Magdalene nude by way of a nameless model. A painting of a nude and a statue of a nude and a photograph of a nude and a film of a nude are not variously real; all are, quite simply, genuine and very real images. A photo of a nude is not more real than a painting of a nude.

For this reason, it appears convenient how proponents of a “no nudity in cinema” position can so easily dismiss the classics. For example, one FB commenter challenged me this way:

How about you produce 3 examples of nudity in art which are not exploitative and we can discuss them. Just as a hint of where I will take you in this exercise, if you produce 2 works of art produced prior to 1800, I’ll call you bluff and ask you to name even one example which treats the human body that way since 1916 (the last 100 years). Trying to justify Renaissance art does not justify 21st century art at all — but I can also explain why those pieces are also not your friend in this discussion.

Best wishes with that.

So in what ways is nudity in “Renaissance art” different than nudity in “21st century art”? Has the human body changed? Have our sexual proclivities changed? Have the biblical injunctions changed? This position requires me to see the Bible’s approach to the human body and art (which is very pre-Renaissance) as binding, the Renaissance view of the body as irrelevant, but the 21st century view as accurate? Truth is, if the Bible categorically condemns viewing ANY nudity, then nude representations in Renaissance art should be just as subject to scrutiny condemnation as should the nudity in Deadpool.

Such objections beg the question. In fact, there is plenty of evidence of a puritanical purging of nudity in Renaissance art. For example, one art history blogger compiled a Timeline of Early Modern Censorship. they include,

c. 1504: Objections arose regarding the nudity of Michelangelo’s “David” (to the point that people threw stones at the statue). It is reported that a skirt of copper leaves was created to cover the statue at one point

Around 1541: Cardinal Carafa and Monsignor Sernini (Ambassador of Mantua) work to have Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” censored, due to the nudity. 1547:

In Spain, the first edition of the Index of Prohibited Books (written in 1547, published in 1551) does not mention nudity specifically, but condemns “all pictures and figures disrespectful to religion”

1555-1559: Pope Paul IV undertakes censorship of nude works of art, which includes the castration of ancient statues.

Dismissing nudity in Renaissance art begs the question and conveniently eliminates a possible argument for a positive (or at least, neutral) representation of nudity in art (which I hope to take up in my final post in this series).

I must admit, the more I listen to objections to cinematic nudity from my evangelical friends, the more it smacks of “white magic.” This is the same “call to purity” that Christian authors and readers have which I addressed in ‘Clean Fiction’ as White Magic. It is the belief that certain words and images have “magical powers” to defile us. It is evangelical superstition. Thus, if I avoid reading profanity, I keep myself unspoiled from the world. Likewise, the same call for “clean fiction” is the one being made by others for “clean cinema.” But is this call inherently superstitious? Is simply seeing a naked or partially nude person — either real or “fake” — an ad hoc sin? I concluded in that article:

The desire to keep our minds focused on what is “pure, lovely, and admirable” is a great thing. Heck, it’s biblical! Nevertheless, that same Bible says that Satan disguises himself as an “angel of light” (II Cor. 11:14). In other words, Satan is more likely to deceive us with something that looks good (“clean”), than something that looks evil. Just because some stories are free of profanity, violence, and nudity, does not make them impervious to spiritual deception. In fact, the desire to read only what is “free of profanity, violence, and nudity” may itself be a spiritual deception. (emphasis in original)

In the same way that Isaiah’s nakedness (Isa. 20:2,3) was intended to shock the moral senses of his audience, isn’t it possible that cinematic nudity can do the same? In my opinion, the full-frontal nudity in Schindler’s List did just that. It did not summon lust. It invoked shame and disgust. Which is what I think the director and actors intended. But to admit this is to concede that some cinematic nudity might be tolerable from a Christian point of view.

The Nudity Isn’t Fake argument suffers on multiple fronts. First is the assumption that nudity is inherently shameful or sinful. While the Bible definitely does not endorse public nudity and exhorts modesty, there are neutral instances of nudity in Scripture. Furthermore, Jesus did not draw the line of “sin” at seeing someone’s nakedness, but at “lusting.” It should also be acknowledged that nudity in cinema is not all the same. The nudity in Deadpool is different than the nudity in The Bible or Children of Men. This concession is extremely important. Yes, juxtaposing fake violence against real nudity has some validity. But even fake nudity appeals to something real and can evoke the same sinful responses. And finally, the Golden Rule argument also applies here: If nudity is not categorically sinful, if it can be shown for artistic (Michelangelo) or emotive purposes (Schindler’s List), if there is a healthy moral intent on the part of the director and actors, if the images are not intended to arouse lust or “concupiscence,” the Nudity Isn’t Fake argument loses some punch.

overseas viagra , what is viagra used for , united healthcare viagra , buy real viagra , buying viagra in canada , viagra mail order uk , where did viagra come from , buy viagra alternative , cost of viagra , cialis transdermal , viagra generic brand , viagra suppliers , purchase cialis overnight delivery , hysterectomy libido viagra , buy viagra now online , brand viagra , buy pfizer viagra , buy prescription viagra , real cialis online , viagra generic , alternative search viagra , professional cialis online , homemade viagra , viagra recipe , viagra sales , one day delivery cialis , h h order viagra , cialis daily , where can i purchase cialis , viagra price comparison , how much is viagra , get viagra avoid prescription , viagra soft tabs 100 mg , viagra rx in canada , viagra in canada , how much cialis , book buy guest sign viagra , viagra buy in uk online , vipps pharmacy , generic viagra in canada , cheapest viagra in uk , viagra pills , cialis soft pills , similar cialis , viagra india , cyalis levitra sales viagra , viagra uit india , buying cialis on line , what color is viagra , get viagra avoid prescription , buy viagra china , express viagra delivery , viagra deaths - Best Price, Fast Delivery , Viagra India

March 26, 2016

Is C.S. Lewis’ ‘Space Trilogy’ a Good Example of ‘Christian Speculative Fiction’?

C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy is often viewed as one of the earliest and best examples of what “Christian speculative fiction” could look like. It’s only reasonable for Christian authors to want to reclaim their literary heritage. But is this a fair comparison?

C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy is often viewed as one of the earliest and best examples of what “Christian speculative fiction” could look like. It’s only reasonable for Christian authors to want to reclaim their literary heritage. But is this a fair comparison?

In one sense, it is. The inclusion of biblical imagery and ideas is the most obvious. Although the Space Trilogy is not the most spiritually explicit of Lewis’ fiction — that would probably go to The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, or Narnia — there is nevertheless plenty of overt “Christian” ideas to be found in the Trilogy. In fact, one of Lewis’ motivations for writing the Trilogy was in response to what he perceived the lack of “Christian realism and Christian hope” in then-contemporary sci-fi and fantasy. In The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings, Philip and Carol Zaleski note that Lewis’ intention in writing Out of the Silent Planet, first book in the trilogy, was indeed to counter the secularism of his time and infuse a genre he loved with “spiritual adventures.”

The model for Out of the Silent Planet (1938) was a childhood favorite of Lewis’s: H.G. Wells ‘ s anti-imperialist First Men in the Moon (1901)… Lewis took his scaffolding from this tale, borrowing from more than a few details of setting and plot, but the edifice he built upon it was altogether different; for he had conceived, by reading David Lindsay ‘ s A Voyage to Arcturus, that the planetary romance could be a vehicle for profound ‘spiritual adventures.’ He thought he could use this form to counter the materialistic picture of the universe that dominated popular science writing.

… [Lewis] had been dismayed to discover that, for some of his own students, such Utopian fantasies [from contemporary science fiction authors] had supplanted both Christian realism and Christian hope. Lewis hoped, in this novel, to present an appealing imaginative alternative. “I like the whole interplanetary idea as mythology,” he told Roger Lancelyn Green, “and simply wished to conquer for my own (Christian) p[oin]t of view what has always hitherto been used by the other side.” (pgg. 253-254)

This desire to “counter” a specific trend or worldview with a biblical message, and employ a specific genre or medium to do so, is central to the motivations of many Christian authors today. Whether romance, historical, or suspense, most Christian fiction exists as an “alternative” to “secular” stories, their ideas and morals. While the particulars may be different, they all share Lewis’ desire to “conquer for [their] own” a point of view that “has always hitherto been used by the other side.” In this way, The Space Trilogy fits easily within the stated goals of many Christian fiction authors. In fact, the final book of the trilogy, That Hideous Strength, addresses head-on specific intellectual and scientific issues of Lewis’ era.

“…Lewis unfolds a broadly satirical supernatural tale that packs in the multitudinous moral and social concerns he had addressed in The Abolition of Man and in his controversial essays of the postwar years: the miseducation of young minds; the evils of eugenics, vivisection, social engineering, ‘humane’ rehabilitation of misfits, and police-state propaganda; the encroachment on the humanities of the fetish for ‘research’…” (pg. 326).

Owen Barfield (one of the Inklings) observed that in That Hideous Strength “somehow what [Lewis] said about everything was secretly present in what he said about anything.” Point being, the novel is more a rebuttal against “the multitudinous moral and social concerns” of his time than it was an escapist tale.

In these senses, it’s easy to include the Space Trilogy under the umbrella of Christian fiction. Not only do we encounter an author with a specifically biblical worldview incorporated into their fiction, but he shares the same goal of many contemporary Christian novelists — to infuse the genres he loves with “spiritual adventures.”

On the other hand, there are many reasons why the Space Trilogy is an extremely uncomfortable fit within today’s brand of Christian fiction.

One reason is the obvious differences between today’s cultural, religious, and publishing climate and that of Lewis’ day. Even though there were decidedly secular ideas (and authors who sought to further them) being embraced in 1930’s Europe, the animosity to religious ideas was not nearly as prolific as it is today. Unlike Lewis, Christian authors now publish in what has rightly been called a post-Christian culture. The complaint that religious content is often met with skepticism, if not antipathy, from general market publishers has some legitimacy. Part of the apologetic for why Christian fiction even exists — the legitimacy of this argument notwithstanding — is that mainstream publishers have grown hostile to the traditional “Christian message.” The Christian publishing industry exists as a reaction to the post-Christianizing of culture.

Furthermore, the publishing market of Lewis’ era was not nearly as partitioned as it is today. The “general market” and the “Christian market” did not exist to the degree they do now. Perhaps this is why Lewis’ books often received attention in “mainstream” literary circles. For example, in reviewing Perelandra, The Saturday Review of Literature raved about the book saying, “C.S. Lewis has gone down again into his bottomless well of imagination for a captivating myth.” Today’s Christian fiction rarely breaks into and receives such attention from mainstream critics and reviewers. Which is one reason it is often (disparagingly) referred to as a ghetto.

Another thing that would definitely work against the Trilogy’s inclusion into today’s Christian fiction would be the genre’s theological and moral strictures. Yes, Lewis’ faith is clearly on display throughout the Trilogy. However, he also integrated pagan mythological concepts into the story. For example, the Oyarsa, Perelandra‘s ruling Intelligence, is “comparable to an archangel or to the planetary archon of Hellenistic and Gnostic lore.” After discovering a reference to “Oyarses” in texts of a lecture by Christian Platonist Bernard Silvestris, Lewis decided to incorporate the concept of a “ruling essence” who “shapes things in the lower world after the pattern of the higher world.” The Zaleskis note,

“There was room for pagan gods in Lewis’s Christian cosmos, provided they appeared as angels or ‘middle spirits,’ archetypes or allegorical figures” (pg. 257).

Making room for “pagan gods” in today’s Christian market would indeed be tricky. At times, especially in the last book of the Trilogy, Lewis even tinkers with more esoteric theological concepts, possibly influenced by Charles Williams (fellow Inkling) who embraced unorthodox views of ritual magic and sex. Compounding this is the inclusion of Merlin in That Hideous Strength who personifies Arthurian elements of the story. Merlin appears as the seventy-ninth successor in history to King Arthur, now a servant to Ransom (the protagonist throughout the Trilogy) and, more importantly, as a wielder of old school magic. The theme of magic is notoriously prickly for many Christian readers and, if the book were published today, would indeed be subject to battery of scrutiny from reviewers and armchair theologians.

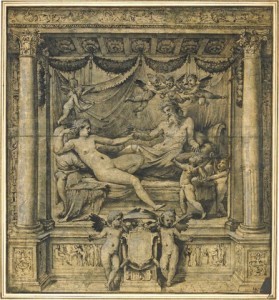

But perhaps the biggest strike against Lewis would be the Venusian Green Lady of Perelandra. She is meant to represent the female half of an unfallen, innocent couple. While this type of speculation would indeed push the boundaries of contemporary Christian fiction, it is the fact that the centerpiece to the story, the Green Lady of Perelandra, whom Lewis conceived as a cross between “a Pagan goddess” and “the Blessed Virgin,” appears naked alongside the protag for the course of the book. In many ways, the idea that a “Christian” character would, for weeks and months, interact with a beautiful naked woman would most likely deeply offend today’s mainstream Christian fiction readers.

The climactic scene of Perelandra is a “kitchen sink” of esoterica as Ransom joins Venus and Mars, bowing before the young King and Queen, before joining in “The Great Dance,” a virtual orgy of light, sound, animals, angels, and all Creation. Here he learns the new Adam and Eve are to be the beginning of a new mankind and will one day go to earth and redeem his planet. Needless to say, the high concepts evoked by Lewis are not only seldom found in much contemporary Christian speculative fiction, they push the doctrinal boundaries that many enforce upon the genre.

Which is why author and journalist Taylor Dinerman, writing for The Space Review, suggests that the contents of the Space Trilogy are an uncomfortable fit within the traditional “Christian morality tale.”

A story that begins with the hero committing an act of criminal trespass and ends with a multi-species festival of sexuality is not, at least superficially, a work that can be described as a Christian morality tale. It is also hard to reconcile orthodox Judeo-Christian monotheistic doctrine with the idea that the classic pagan gods like Venus and Mars were in some way angels of the Lord. Yet C.S. Lewis, best known as the author of The Chronicles of Narnia, managed to bring it off, he even mixed in a bit of the Arthurian matter of Britain and a reference to his friend JRR Tolkein’s mythic fiction.