Paul Vitols's Blog, page 6

February 8, 2020

when reading is not just reading

It’s 5:17 p.m., and I’m in the midst of my daily “reading” block. I put it in quotation mark because I also do things other than reading in the strict sense.

My reading block is structured. The first part of it is dharma reading: I continue to study the Buddhist teachings. I put this first as a sign to myself that, because it concerns my spiritual welfare and my ultimate good, it is the highest priority. (Whether I truly live that outlook in the rest of my life is less clear.) Right now I’m reading The Four Noble Truths by Geshe Tashi Tsering, a Tibetan monk who, according to the book’s Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, is a year older than I am: born in 1958.

Second is fiction reading. My current novel is The Subtle Knife by Philip Pullman, book 2 of the series His Dark Materials. I’m enjoying it, the more so because the series title and the subject matter of the trilogy are taken from Milton’s Paradise Lost. I think that’s a fantastic idea for a “young adult” fiction project. The work makes a big deal of the distinction between children and adults—much like my own television series, The Odyssey.

The third part of my reading block is devoted to the Great Books, that is, the Encyclopedia Britannica Great Books of the Western World series, published in 1952. I have a used set of these books (54 volumes) in my library (the word I use to designate our freezer room, which does have three Ikea Billy bookcases standing in it), and I intend to read the whole thing, and read it carefully.

The specific task I have left off doing just now is, what’s the word, processing Aristotle’s Poetics. For my reading of the Great Books is not just about reading. I read the books with a yellow highlighter (I use Sharpie highlighters made in the United States), and I highlight them in a specific way. I highlight complete sentences in such a way as to compress the book into a condensed, Reader’s Digest version of itself. In effect I read each book as an editor, which makes me pay careful attention to what I’m reading.

I’m just about done with you, Aristotle

Highlighting done, I then type the highlighted text into a Word document, one document for each book. Now I have my own Reader’s Digest version—but I’m still not done. There is a final step.

One of the exciting parts of the Brittanica Great Books series is a pair of volumes near the beginning of the set: volumes 2 and 3 constitute the Syntopicon of the Great Books. It’s a word formed from Greek words to mean “a collection of the topics.” The editor of the Syntopicon, Mortimer J. Adler, along with his staff, combed through all the Great Books to identify the ideas or topics that they addressed in each part, and created a kind of concordance that lets you find all the places in the whole set of books where each topic is treated. It’s an amazing, one-of-a-kind thing, and represents a huge amount of intellectual labor. For my own part, I decided to create a kind of Syntopicon of my own—a set of Word documents that mirrors the topics in the Syntopicon. The final phase of my reading process is to go through my newly typed condensed book, copy each part of it, and paste each part into the relevant Syntopicon documents by topic.

This is the process I’m now involved with in Aristotle’s Poetics. Some parts of this I’ve pasted into my document for Tragedy; other parts I’ve pasted into my document for Poetry; other parts I’ve pasted into my document for Comedy. And so on. I call this process indexing. When I have copied and pasted all the passages in a given book, I type at the top of the condensed-book document: “Book completely keyed & indexed.” For me, that book is then done.

As I process different books, my own Syntopicon (or, simply Research, as I call them) documents gradually get fleshed out. For example, my document on Tragedy now contains extracts from 20 different books, from The Anatomy of Story by John Truby to The Varieties of Religious Experience by William James.

So: right now it’s Aristotle’s Poetics that occupies the Great Books block of my reading period. It’s quite a short work and I’m most of the way through.

Friends, this is my idea of having fun. It’s a scholarly, librarianlike task that feels profoundly wholesome to me. It’s my own personal library of ideas, and I love the prospect of spending the rest of my life, however much remains to me, doing this.

There’s more to my reading period—and to my life—but I will talk about those things another time.

The post when reading is not just reading appeared first on Paul Vitols.

February 2, 2020

page fright

The above title is an expression I came up with as an alternative to the familiar phrase “writer’s block.” I thought that it encapsulated the emotional quality of the experience, rather than the more psychoanalytic or even engineering tone of a “block,” while also punning cleverly on the familiar term “stage fright.” For it you look at what keeps (us) writers from writing, I think in every case you will find that it is fear.

I’ve never really thought of myself as suffering from writer’s block or page fright; writing has always been easy for me, and I don’t find it difficult to turn my thoughts and experiences into words. And yet, and yet. Look at this here blog, a thing that I not only write but also publish. If writing is easy for me, what could be simpler than to crack off a blog post and publish it? No obstacle of any kind hinders me. And yet I published my last post here on December 6, 2019, almost two months ago. What happened—or failed to happen? According to my just-presented theory, fear happened.

Fear of what? What am I afraid of? Let me think. I’m just searching my mind. One thing that swims up: fear of being boring. I think I have a fear that if I just write and publish any old thing, it may be half baked and uninteresting. This may come from a deep-seated anxiety, stemming from earliest childhood, that I need to impress. To be humdrum or ordinary is to be somehow worthless or even nonexistent. The astrologer in me can see signs of this in my birth chart.

I think I took a wrong turn at Albuquerque. . . .

Another possible fear is of being unfocused or off message. I created this website and blog in order to promote myself and my works. It exists to promote my “brand.” This “marketing” outlook subtly affects how I approach topics here and what I feel I can write about. And so I prune away ideas, even unconsciously, that I think might not fit with the “mission” of my site.

I’m not sure whether I have discovered all my blog-related fears here, but this is already enough, I think, to explain my hesitations and absences. I think: “What can I come up with that is both interesting and on message?” And often the answer is: “Well, nothing, right now.” And another week slips by, and another—and another.

Well, I want to break with that hangup. Call it a New Year’s resolution if you will, but I want to post more often and more freely. Here is where I need to be myself, with all of my too-many interests, inconsistencies, and warts.

I just thought of another fear. It’s that if I started talking about all the things that I think about and that interest me, I will unleash a torrent. For I am a man of many and diverse interests. And there is an anxiety that my blog and my writing and my career may, in dishing out everything, wind up being about nothing.

Well, and what if they do? It will mean that that’s what I was about all along—nothing. So be it.

So I suppose this is a mini manifesto for this blog. Brace yourself for a torrent of nothing!

Help me create more by becoming one of my Patreon patrons. If you’d like to support my work without spending money, I have just the page for you.

The post page fright appeared first on Paul Vitols.

January 1, 2020

page fright

The above title is an expression I came up with as an alternative to the familiar phrase “writer’s block.” I thought that it encapsulated the emotional quality of the experience, rather than the more psychoanalytic or even engineering tone of a “block,” while also punning cleverly on the familiar term “stage fright.” For it you look at what keeps (us) writers from writing, I think in every case you will find that it is fear.

I’ve never really thought of myself as suffering from writer’s block or page fright; writing has always been easy for me, and I don’t find it difficult to turn my thoughts and experiences into words. And yet, and yet. Look at this here blog, a thing that I not only write but also publish. If writing is easy for me, what could be simpler than to crack off a blog post and publish it? No obstacle of any kind hinders me. And yet I published my last post here on December 6, 2019, almost two months ago. What happened—or failed to happen? According to my just-presented theory, fear happened.

Fear of what? What am I afraid of? Let me think. I’m just searching my mind. One thing that swims up: fear of being boring. I think I have a fear that if I just write and publish any old thing, it may be half baked and uninteresting. This may come from a deep-seated anxiety, stemming from earliest childhood, that I need to impress. To be humdrum or ordinary is to be somehow worthless or even nonexistent. The astrologer in me can see signs of this in my birth chart.

Another possible fear is of being unfocused or off message. I created this website and blog in order to promote myself and my works. It exists to promote my “brand.” This “marketing” outlook subtly affects how I approach topics here and what I feel I can write about. And so I prune away ideas, even unconsciously, that I think might not fit with the “mission” of my site.

I’m not sure whether I have discovered all my blog-related fears here, but this is already enough, I think, to explain my hesitations and absences. I think: “What can I come up with that is both interesting and on message?” And often the answer is: “Well, nothing, right now.” And another week slips by, and another—and another.

Well, I want to break with that hangup. Call it a New Year’s resolution if you will, but I want to post more often and more freely. Here is where I need to be myself, with all of my too-many interests, inconsistencies, and warts.

I just thought of another fear. It’s that if I started talking about all the things that I think about and that interest me, I will unleash a torrent. For I am a man of many and diverse interests. And there is an anxiety that my blog and my writing and my career may, in dishing out everything, wind up being about nothing.

Well, and what if they do? It will mean that that’s what I was about all along—nothing. So be it.

So I suppose this is a mini manifesto for this blog. Brace yourself for a torrent of nothing!

The post page fright appeared first on Paul Vitols.

December 6, 2019

novel vs. novel 4: journeys local and galactic

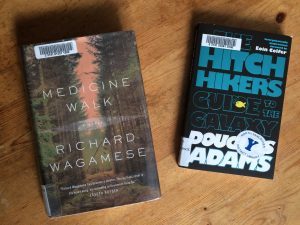

The two recently read novels I look at today, Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, are, in many ways, like night and day. The two works do have some similarities: they are both relatively short and written in lean, minimalist prose; they both, as the title of this post suggests, are accounts of adventurous journeys. Also, the authors were men who died at relatively young ages, Wagamese in 2017 at age 61, and Adams in 2001 at age 49. And, in a certain way, both novels are the products of suffering: Wagamese writes from a well of firsthand knowledge of the pain and injustices borne by aboriginals in Canada, while Adams, like many another comedian, grappled with depression throughout his life.

Men on the move

Despite these parallels, it would be hard to find two books that differ so much in outlook and mission as these two. Wagamese, a half-breed Indian who lived in the city of Kamloops in the interior of my own home province of British Columbia, writes with great depth of feeling and knowledge about the backcountry of B.C. It seems clear that his protagonist, 16-year-old Franklin Starlight, gets his own love of that world from his creator. There is a strong sense here of the power of nature to heal, and nature has her work cut out in this case, for Franklin finds himself suddenly taking on an unwelcome burden: to take his sick, estranged father Eldon deep into the woods so that he can die and be buried there. A life of alcoholism and dissipation have killed the still young Eldon—or, more likely, the wounds that led to that feckless life are finally proving fatal. Although Eldon knows nothing about Indian traditions, his journey into the woods, guided by his son, for death and burial, is the “medicine walk” of the title. A past surfaces, filled with pain, guilt, and remorse.

Adams, for his part, makes light of the conception, birth, and career of the franchise he created with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Like the story itself, he portrays it as a series of serendipitous events, chance encounters, and flukes. As a science-fiction-loving backpacking youth in Europe, he hit on the idea of a hitchhiker’s guide for traveling the galaxy, and some years later turned this idea into a series of radio sketches for the BBC. It quickly found an audience, and Adams, a hitherto marginal and struggling writer, had discovered his magnum opus.

I like to compare novel openings, so let’s do that. Starting with Medicine Walk, here’s the beginning of chapter 1:

He walked the old mare out of the pen and led her to the gate that opened out into the field. There was a frost from the night before, and they left tracks behind them. He looped the rope around the middle rail of the fence and turned to walk back to the barn for the blanket and saddle. The tracks looked like inkblots in the seeping melt, and he stood for a moment and tried to imagine the scenes they held. He wasn’t much of a dreamer though he liked to play at it now and then. But he could only see the limp grass and mud of the field and he shook his head at the folly and crossed the pen and strode through the open black maw of the barn door.

The old man was there milking the cow and he turned his head when he heard him and squirted a stream of milk from the teat.

“Get ya some breakfast,” he said.

“Ate already,” the kid said.

“Better straight from the tit.”

“There’s better tits.”

The old man cackled and went back to the milking. The kid stood a while and watched and when the old man started to whistle he knew there’d be no more talk so he walked to the tack room. There was the smell of leather, liniment, the dry dust air of feed, and the low stink of mould and manure. He heaved a deep breath of it into him then yanked the saddle off the rack and threw it up on his shoulder and grabbed the blanket from the hook by the door. He turned into the corridor and the old man was there with the milk bucket in his hand.

The prose is clean, plain, and vivid. The farmstead comes alive with sensory details and a couple of striking metaphors: the “inkblots” of the footsteps in the frost, the “black maw of the barn door.” There is a certain sense of mystery, perhaps a fairy-tale quality, evoked by the fact that the characters are not named; so far they are only a “kid” and an “old man.” This raises the question of their relationship, which is clearly familiar and close without, seemingly, being in the nature of a family tie. It also suggests a missing element: the adult man who naturally stands between the kid and the old man. The story will show that this man—the kid’s father—is missing indeed, and this absence lies at the crux of the story. And the relationship between the kid and the old man is a mystery which will the story will only gradually resolve.

Speaking for myself, I found the opening of the novel intriguing and inviting; I wanted to read on.

Let’s compare it now with the opening of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. This edition of the book included a preface by the author, then the book proper begins with a 2-page prologue. I’ll skip those and present the first part of chapter 1, where the story begins:

The house stood on a slight rise just on the edge of the village. It stood on its own and looked out over a broad spread of West Country farmland. Not a remarkable house by any means—it was about thirty years old, squattish, squarish, made of brick, and had four windows set in the front of a size and proportion which more or less exactly failed to please the eye.

The only person for whom the house was in any way special was Arthur Dent, and that was only because it happened to be the one he lived in. He had lived in it for about three years, ever since he had moved out of London because it made him nervous and irritable. He was about thirty as well, tall, dark haired and never quite at ease with himself. The thing that used to worry him most was the fact that people always used to ask him what he was looking so worried about. He worked in local radio, which he always used to tell his friends was a lot more interesting than they probably thought. It was, too—most of his friends worked in advertising.

On Wednesday night it had rained very heavily, the lane was wet and muddy, but the Thursday morning sun was bright and clear as it shone on Arthur Dent’s house for what was to be the last time.

It hadn’t properly registered yet with Arthur that the council wanted to knock it down and build a bypass instead.

Here too the prose is lean and clear. Unlike the opening to Medicine Walk, here there is no figurative language to speak of, but we do have a narrator who is ironic and funny. We are introduced to the principal character (we won’t really be able to call him a hero), Arthur Dent, an ill-at-ease 30-year-old. And we learn, before Arthur does, that the powers that be have decided to bulldoze his house to build a bypass. Later this will become funnier when we discover that Arthur’s house is the type of a greater bulldozing about to come: that of planet Earth, which is to be demolished to make way for a galactic bypass! Even when Arthur finds out that his house is set for demolition, his citizen’s outrage is still only a dwarf version of what he should really be feeling.

Medicine Walk proceeds more or less as a classic archplot: Robert McKee’s term for a classically structured story. There is a hero, 16-year-old Franklin, who grapples with a difficult problem, with the stations of his journey marked by painful revelations. The Hitchhiker’s Guide is structured as what McKee would call an antiplot: it is an anti-story in which ridiculous coincidences, freak occurrences, and impossibilities take the place of the logical flow of cause and effect that drives conventional stories. In this way it bears resemblance to such works as Wayne’s World or Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

I rated both these books as 4 stars out of 5 on Goodreads. I decided that I would like to read another book by Richard Wagamese, and added one to my reading list; but I’m not sure about Douglas Adams. I appreciated his cleverness and did get some chuckles while reading, but I wonder whether reading more of the same would be the best use of my limited reading time. I’m not a—what’s the term, “hikey”?—that much is sure. One thing that might tempt me back is to see more of the best character in the book: the morose robot Marvin, who I feel pretty sure is the author’s proxy in the story, a kind of techno-Eeyore.

These two works are a great example of what a wide range is embraced by the term novel. Nonetheless, my sense is that these authors are both men of serious purpose. In the case of Wagamese this is obvious; in the case of Adams it’s concealed under the play of comedy. He looks out at the universe—all of it—in search of some kind of sense. He doesn’t find it, which failure provides laughs for the reader, but one suspects that Adams’s struggle with depression meant that, deep down, he didn’t think it so funny.

The post novel vs. novel 4: journeys local and galactic appeared first on Paul Vitols.

November 30, 2019

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese: the painful path to forgiveness

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A powerful and unflinching tale of healing and forgiveness. This novel had special interest for this reader for a couple of reasons. For one thing, it is set in British Columbia, where the author eventually made his home near Kamloops, and is filled with a powerful and immediate intimacy with the backcountry of the interior of B.C. For another, the story deals with the sometimes fraught terrain of the relationship between father and son. I was slow to realize that this was a deep theme of my 1990s TV series, The Odyssey. In a wider sense, it also looks at the world of maleness more generally. Where other writers tiptoe around this, Wagamese rolls up his sleeves and gets under the hood.

The prose is lean, poetic, and self-assured. The hero is a 16-year-old boy, Franklin Starlight, a half-breed Indian (“breed,” as these characters call themselves) who lives and works on the farmstead of a white character identified only as “the old man.” It’s a good life: Franklin has become a skilled farmhand and woodsman, and can’t imagine anything better than living and working in this country. But there are unhealed wounds lying beneath the idyllic surface of life: Franklin’s father, Eldon, a feckless alcoholic, makes the occasional appearance in his life, creating feelings of shame and bitter disappointment in the boy. Of his mother he knows nothing; no word has ever been said about her, except that it is Eldon’s place to tell Franklin about the circumstances of his birth and early life—which he has not done.

Now liver disease has caught up with Eldon, and he has not much time left. And Franklin finds himself making a final trek with his father into the bush so that Eldon can die in a special place there. On that journey, the issues between them come to light, along with the history that has led to their situation. It’s a painful journey, but a necessary one.

The author, Richard Wagamese, who, sadly, died in 2017 at age 61, knew whereof he wrote, for he was an aboriginal who grew up with the full measure of tragedy borne by so many Indians in Canada, including the systematic abuses of the residential school system. He became an addict, a street kid, and a jailbird. Eventually he became a journalist and writer, and moved from his native Ontario to B.C. When he writes about pain and about emotional scarring, he writes what he knows, and it comes through as deeply authentic.

There are many “5-star” aspects to this novel, but in the end I have rated it with 4 stars. One issue with a tale of this kind is that it deals quite a lot in flashbacks, and these are difficult to handle, since they slow down a story. Another slight issue for me was that the dialogue, although authentic and gutsy, is too similar between all the characters: they all speak the same way. It would have been good to distinguish between the characters in this respect. In other ways the characters are well drawn and distinct, but I think the author could have done more here.

But I admired many things about this book. One was that the characters do not dwell on the social causes of their suffering. They don’t spend time blaming society or white people, or even full-blood Indians who also look down on “breeds”; they play the cards that have been dealt to them, and take personal responsibility for their lives, no matter how difficult or mismanaged these might be. They have drunk the cup of suffering to the bottom, but they are soldiering on. There is courage here, and benevolence, and wisdom, along with the squalor and vice of exploded lives.

Franklin Starlight is on a hero’s journey in the backwoods of B.C., fraught with perils and with pain. It’s a strong and searching tale.

The post Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese: the painful path to forgiveness appeared first on Paul Vitols.

November 21, 2019

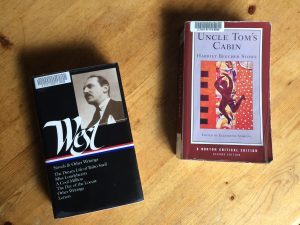

novel vs. novel 3: souls in chains

The last two novels I read were The Day of the Locust by Nathanael West and Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Again, I do my best to read the novels on my reading list in the order in which they’re added; something about this approach, which feels both systematic and random, gratifies me. Does it put me somewhere on an OCD spectrum? Ah well, it’s harmless—and it’s fun!

American dream—or nightmare?

Here again we have two works that appear to have very little in common, one a short work published in 1939, the other a more massive work of “activist” fiction published in 1852. They both qualify very well, though, as Americana: West’s novel looks at a few obscure denizens of the Oort Cloud of bit players, wannabes, and parasites of 1930s Hollywood; Beecher Stowe’s novel takes aim at the polarizing institution of slavery as it existed in the United States of the early 1850s. Locust is humorous, ironic, dark, and apocalyptic; Uncle Tom is passionate, self-assured, spiritual, and heartfelt.

Let’s look at how these two novels open. First, The Day of the Locust:

Around quitting time, Tod Hackett heard a great din on the road outside his office. The groan of leather mingled with the jangle of iron and over all beat the tattoo of a thousand hooves. He hurried to the window.

An army of cavalry and foot was passing. It moved like a mob; its lines broken, as though fleeing from some terrible defeat. The dolmans of the hussars, the heavy shakos of the guards, Hanoverian light horse, with their flat leather caps and flowing red plumes, were all jumbled together in bobbing disorder. Behind the cavalry came the infantry, a wild sea of waving sabretaches, sloped muskets, crossed shoulder belts and swinging cartridge boxes. Tod recognized the scarlet infantry of England with their white shoulder pads, the black infantry of the Duke of Brunswick, the French grenadiers with their enormous white gaiters, the Scotch with bare knees under plaid skirts.

While he watched, a little fat man, wearing a cork sun-helmet, polo shirt and knickers, darted around the corner of the building in pursuit of the army.

“Stage Nine—you bastards—Stage Nine!” he screamed through a small megaphone.

There’s a lot here. It starts in seeming confusion, with some kind of military rout taking place outside a man’s office. The scene pays off with the comic revelation that these are actors—we’re in Hollywood. The narrator lingers with a certain obsessive glee over the details of the soldiers’ kit, and it’s not completely clear whether this glee is the narrator’s own or Tod Hackett’s; but as the book goes on, the narrator will show a continuing concern with how people dress and groom themselves. I sensed that this was a preoccupation of West himself, a man who died young (age 37) in a car crash, but it is a fitting concern too for image-obsessed Hollywood. The question simmers implicit: what’s underneath the clothes? Anything?

The first sentence is constructed with care; let’s take a look at it:

Around quitting time, Tod Hackett heard a great din on the road outside his office.

Quitting time is the time we knock off work, but it could also refer to a time when we give up a job or the pursuit of a dream; it can also serve as a metaphor for death. All of these notions will prove relevant to the coming story.

The character is named Tod Hackett. According to Wikipedia, the name Hackett is thought to derive from hake, a codlike fish. But the verb phrase hack it means “to cope” or “to be successful,” and, again, both these senses will prove relevant. The name Tod means “fox,” but it’s also German for “death”; and this feels the more relevant, since Tod is more usually spelled Todd. In the first five words, then, we have the issues of life and death, success and failure.

The great din on the road foreshadows events in the climax of the novel. It suggests public disorder, rioting, or at least partying. A din is “a welter of discordant sounds”: sound without meaning, sense, or purpose. Noise. It is loud without communicating anything. As for the road, it was built to go somewhere, but here it is merely a place where disorder is happening; it’s not going anywhere. Tod first hears the din, then looks out on the seeming rout. He is a witness to it; and this too points to his function in the story ahead.

All of that is in the first sentence, which tells us that The Day of the Locust is a significant literary work.

Now let’s look at the opening of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Chapter 1 is entitled “In Which the Reader Is Introduced to a Man of Humanity”:

Late in the afternoon of a chilly day in February, two gentlemen were sitting alone over their wine, in a well-furnished dining parlor, in the town of P——, in Kentucky. There were no servants present, and the gentlemen, with chairs closely approaching, seemed to be discussing some subject with great earnestness.

For convenience sake, we have said, hitherto, two gentlemen. One of the parties, however, when critically examined, did not seem, strictly speaking, to come under the species. He was a short, thick-set man, with coarse, commonplace features, and that swaggering air of pretension which marks a low man who is trying to elbow his way upward in the world. He was much over-dressed, in a gaudy vest of many colors, a blue neckerchief, bedropped gayly with yellow spots, and arranged with a flaunting tie, quite in keeping with the general air of the man. His hands, large and coarse, were plentifully bedecked with rings; and he wore a heavy gold watch-chain, with a bundle of seals of portentous size, and a great variety of colors, attached to it,—which, in the ardor of conversation, he was in the habit of flourishing and jingling with evident satisfaction. His conversation was in free and easy defiance of Murray’s Grammar, and was garnished at convenient intervals with various profane expressions, which not even the desire to be graphic in our account shall induce us to transcribe.

His companion, Mr. Shelby, had the appearance of a gentleman; and the arrangement of the house, and the general air of the housekeeping, indicated easy, and even opulent circumstances. As we before stated, the two were in the midst of an earnest conversation.

Here we have a much different narrator, although the narrators do share certain traits, and indeed the two openings are not as different as they may appear. One big difference is that West is a self-conscious literary artist, while Beecher Stowe is not. Beecher Stowe’s first sentence is not packed with symbolic meaning; it is scene-setting, plain and simple. But her narrator, like West’s, is a humorist; but the glee that West’s narrator lavishes on the faux soldiers of his scene is lavished here instead on the kit and comportment of one of the characters (whose name will prove to be Haley). And while West’s narrator comes across as a bemused student of militaria, Beecher Stowe’s is a right-thinking, middle-class Christian woman who knows who is who and what is what. Her arch references to Haley’s vulgarity are funny, like watching a prim but knowing schoolteacher hold up a stink-bomb with a pair of tongs. She knows these men, Shelby and Haley, inside and out; she knows them better than they know themselves.

West, the literary artist, has more recourse to figurative language than does Beecher Stowe. His short first paragraph contains the groan of leather and the tattoo of a thousand hooves: instances of metaphor and hyperbole (unless there really were 250 horses out there). And as Locust proceeds, striking figures of speech pop up repeatedly to jolt the imagination. Uncle Tom’s Cabin makes relatively little use of figures; its power derives from its plain portrayal of a fascinating and emotionally charged world.

On Goodreads I wound up giving The Day of the Locust 4 stars, while I gave Uncle Tom’s Cabin 5 stars. I appreciated West’s artistry and looked on with a mixture of amusement and horror at his depiction of anomie in the wasteland surrounding the Hollywood dream factory, but when I read Uncle Tom’s Cabin I laughed, I wept, and I was inspired. What would Uncle Tom make of the “free” white folks blundering their way through life in West’s Hollywood? Tod Hackett develops a fixation with a sexy walk-on actress; when he gets drunk he even considers raping her. Uncle Tom would no doubt shake his head. He may not be much at reading, but he understands clearly that freedom means, first of all, freedom from sin; if we have that, then our soul is emancipated, and what happens to our body is a comparative trifle. The characters in The Day of the Locust have a certain complexity, but they’re shallow; Uncle Tom is simple but deep. We all need to tend to our souls—even if we don’t think we have one.

The post novel vs. novel 3: souls in chains appeared first on Paul Vitols.

November 17, 2019

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe: telling it like it was

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I was in high school when I learned the word didactic: “intended to convey instruction and information as well as pleasure and entertainment.” I’m not sure that we were taught to frown on didactic works of literature as inferior, but I certainly developed a negative stance toward it. The idea of using the art of literature to preach a sermon of some kind—of any kind—disgusted me. “Didactic” literature was obviously inferior to works that explored the mysterious and gray areas of life: the world that we all actually live in.

I thought this even as some of my favorite books of that time, that is, my teen years, were things like Nineteen Eighty-four by George Orwell and Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand: poster children for didactic literature. I continued to think it right into adulthood and up to the present time—right up to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Here is a work of literature that makes no bones about its didactic mission: to wake the reader up to the fact that slavery is an evil institution and a great and hypocritical blot on any society, but especially one that prides itself on the values of freedom and the rights of man. I forget exactly how it made its way onto my reading list, but it may have been while watching an episode of Jeopardy! two years ago, and an answer on the show reminded me that I had not read this classic work. When I finally got a rather massive and imposing-looking critical edition from the library, I was not optimistic. The name Harriet Beecher Stowe sounded like the name of a prim schoolmarm of the era—1852 (although the little vignette photo on the back cover looks more thoughtful and poetic, a 19th-century Virginia Woolf)–and I was expecting a long sermon telling me something I already knew perfectly well: that slavery is Wrong and a Bad Idea.

There’s an old adage in storytelling that you should give the audience what they want, but not the way they expect. Well, with Uncle Tom’s Cabin this might need to be revised: give the audience what they expect—but not the way they expect it.

For the reader can be in no kind of doubt of what the mission of the novel is: the word “activist text” is in the first line of the blurb on the back cover, and the book’s preface starts by announcing that “Harriet Beecher Stowe had to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her political convictions and religious faith, she believed, gave her no choice.” Okay, antislavery tract it is—408 dense pages of it. Let’s go!

From the start I was drawn in by the author’s vivid portrayal of the time, the place, and especially the people. The opening scene has two men negotiating the sale of some slaves in Kentucky: the seller a cultured and decent man who has been driven to this pass by financial pressure, the buyer a vulgar but prosperous slave trader. The chief item of sale: one Uncle Tom, a mature slave of strong ethics and impeccable character. The seller, Mr. Shelby, hates to see him go, and knows he is sending him to an unpleasant fate by “selling him down the river”–meaning down the Mississippi to New Orleans, where slaves were auctioned for hard toil and a short life on the plantations of the Deep South.

Soon we are introduced to Tom, and to other slaves on the place, such as his wife Chloe, the cook, all rendered vividly in their behavior and dialogue. My main exposure to American slave culture had been via Gone with the Wind, which has generated some controversy over its allegedly cartoonish portrayal of slaves, but an early thought in reading Beecher Stowe’s book was, “Holy smokes—Margaret Mitchell boosted her slave material right out of Uncle Tom’s Cabin!” Here we have those quaint and comical portrayals, but in this case offered by an author who was familiar with them at first hand, and who had no hostile or satirical intent (not saying that Mitchell had these, either). For while she portrays the white owners sympathetically—those who are deserving of sympathy—her heart is with the slaves, and this comes through strongly from first to last. The slaves are various: some roguish, others foppish, deceitful, superstitious, irritable, or evasive, and the uneducated ones do indeed talk much like Mammy of Gone with the Wind. The point is that they’re human beings doing the best they can, living in captivity, mostly uneducated, without rights, and routinely subjected to harsh injustice. Two common forms of this are the rending of families, especially the taking of children from their mothers and selling them off, and the pressing of attractive girls into the role of concubines.

Friends, I was hooked. Although I read for hours each day, I almost never have the experience of reading a book that I can’t stop reading. Again and again with Uncle Tom’s Cabin I found myself saying, “Okay, I’ll just read to the end of this chapter,” only to break my promise to myself and keep going because I couldn’t stop! I don’t read that way; I’m not that type of reader; but Uncle Tom’s Cabin made me one for the duration of this book.

The novel follows the fate of Uncle Tom and a few other slaves who make their way from the Shelby estate to other places. Tom wants only to return to Chloe back in Kentucky; the others have the ambition of making it to Canada and liberty. It’s all keenly suspenseful, and your heart—my heart—is with those poor slaves all the way.

The novel is not without its imperfections. Harriet Beecher Stowe made no literary claims—quite the reverse. She had married an erudite but poor man, and as her family grew (she had seven children), she felt the pinch of poverty, and found that she was able to make money by selling pieces of writing. She had a knack that helped her squeak by. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not a potboiler, though; it was a work of passion and conviction which its author had no notion of making money from. No one was more surprised than she was when it became an instant bestseller, earning her $10,000 in its first month out. (The book has never been out of print since then.) Beecher Stowe did not see herself as a literary figure or an artist. Asked to describe herself, this is what she came up with:

To begin with, then, I am a little bit of a woman,–somewhat more than forty, about as thin and dry as a pinch of snuff—never very much to look at in my best days and looking like a used up article now.

Beecher Stowe was not an author, but a Christian woman who saw her own country and society as living in appalling sin, and in deep denial about it. She saw a lot of people sleepwalking to damnation, drugged with ease and comfort, carrying a large toolkit of rationalizations that they wielded with well-practiced skill. The slave states of the South were of course in a bad way, but she was galvanized to action by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required all U.S. citizens to return runaway slaves to their owners. This law made Northerners complicit in the institution of slavery, making criminals out of those who refused to act as slave-catchers. Beecher Stowe could not remain silent, and she didn’t. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not a work of art but a cri de coeur; and Harriet Beecher Stowe was not an artist but a genius.

One of the most powerful aspects of the novel is its spirituality. Uncle Tom and other slaves have an unshakable Christian faith. He can barely read but he knows his Bible and can quote it right to the point when he needs to. Christian virtue pervades his being, and no force on Earth can stamp or whip it out of him. All the while he remains a very human and humble character. For me, a growing mystery, as I read, was how the label “Uncle Tom” has become a term of abuse: for a black American to be called an Uncle Tom is a grave insult, suggesting a fawning subservience to white people. It’s true that Uncle Tom is deferential toward his masters—his owners. But he is this way because it’s the situation that God has placed him in, and so he lives it with integrity. In one of the novel’s most powerful moments, Tom observes that his masters have a Master of their own, to whom they will have to render an account in due course. No matter how he is abused, if he were free to choose, he would much rather be himself than any of them. For this reader, this is what being an “Uncle Tom” really means. Tom knows something that his oppressors and most of us readers don’t: the world is much vaster than what we see, and we are all spiritual beings first and foremost. This perspective runs as a ground note underneath the whole novel.

As I reflected further on didacticism in art, it dawned on me that what may be the greatest work of imaginative literature of all time, namely the Divine Comedy of Dante, is also, arguably, the most didactic. Writers write because they have something to say. If it is something definite, then perhaps their work could be called didactic. But if it is said with power, conviction, and great emotional force, then it could be called brilliant. Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a work in this class.

The post Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe: telling it like it was appeared first on Paul Vitols.

November 9, 2019

my reading list and how it gets that way

Right now I’m reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. I’ve borrowed the Norton Critical Edition from the North Vancouver District Public Library (the only edition that was on the shelves when I went looking), and I’ve made it to page 60. So far, I must say, I’m surprised at how much I’m enjoying it: an overtly didactic work published in 1952—how good could it be? Rather good!

But if I didn’t expect to enjoy it, how did I end up reading it? you might ask. Well, it was on my reading list. But how did it get there? Now things get foggy. I had long been aware of it and knew it was a classic novel, and something in particular must have prompted me to add it to my list a couple of years ago. It will have been in 2017, for I added it not long after I added A Man Called Ove, which was in June 2017, since I remember the occasion on which I added that. Most likely I read a reference to it somewhere that jogged my memory, or, just as possibly, it was an answer on Jeopardy! that prompted me to think, “Oh yeah—I’ve always wanted to read that.” Out with the iPhone, and I typed the title and author in a Note labeled, simply, “Books.” Looking at the list now, there I see it, sandwiched between The Book of the Courtier by Baldesar Castiglione and a book called Description by one Monica Wood, which I have yet to acquire or read.

I got my iPhone 5S in November 2014: my first smartphone and indeed my first cellphone. Noticing the Notes app that came preinstalled, I got the idea of creating a reading list for myself—something I had never created in the world of paper and ink. My very first entry says simply “Penelope Fitzgerald”: no title attached. I recall too how this entry got there. I had read an article about Penelope Fitzgerald, possibly in The Times Literary Supplement, and was interested in her because of her late-starting career and the seeming literary depth of her writing. I no longer had the Supplement and could not remember any of her books’ titles, but I remembered Penelope Fitzgerald, and so, casting around my mind for something to start my official reading list with, I picked her name and typed it in. List started!

An iPhone making itself useful

(I did go on to read a couple of books by Penelope Fitzgerald, and enjoyed them quite well—but that’s another subject.)

The next entry was Augustus by Adrian Goldsworthy, a highly readable and prolific author of ancient history. This book I still don’t have. I will have been encouraged to add it because of how much I enjoyed Goldsworthy’s Caesar, which I acquired in 2008; but as for what specifically prompted me to add this one, I don’t recall. Possibly it was referenced in another book, and I typed it in.

There are different paths to my reading list: reviews, references in other books, the results of Amazon searches, even the odd personal recommendation, as in the case of A Man Called Ove. I thought it might be fun to look at some more recent additions whose provenance I do remember.

Let’s start at the end: the most recent addition:

The Stages of Higher Knowledge by Rudolf Steiner

This one I added this morning while typing notes from last night’s reading period. I had just started Steiner’s book How to Know Higher Worlds, first published in 1909, and in his preface he mentions a succeeding work that would be a continuation of his discourse. I highlighted the title while I was reading, then, this morning, as I was typing the highlights into a Word document, I paused to add this work to my iPhone reading list. So this was a reference from a book I’m currently reading.

The item that precedes it is:

The Book of the New Sun by Gene Wolfe

This too is an entry I made this morning. It’s unusual for me to make 2 entries on the same day, although not unprecedented. Usually days or weeks go by without my adding to the list. But if something grabs my attention, I add it. This book came from an answer on Quora. The question was “Why do some people believe that Dune is the greatest sci-fi novel ever written?” and it showed up in the Quora Digest e-mail that I get each day. The top answer was by one Eric Van, someone who plans sci-fi conferences. He takes a good stab at surmising why some people regard Dune as the greatest, but he notes in a postscript that his own pick for greatest sci-fi novel—something which he distinguishes from best sci-fi novel—is the above-named work. Intrigued by this knowledgeable recommendation, I hastened to add it to my reading list.

Maybe one more. It’s an entry I made 2 or 3 days ago:

Plot vs. Character by Jeff Gerke

This was another reference from a book, specifically Creating Character Arcs by K. M. Weiland. Lately I’ve been putting intense (for me) effort into sorting out the plot of my epic, The Age of Pisces, and in the course of doing this I have been reviewing the various texts in my library on the art of structuring stories. Weiland’s is one of these—a very good one—and her quoting Gerke’s work in a couple of places made me curious to see more of his book. On the list it went.

So there you have it: a snapshot of my reading list. I’ll never read them all, but neither are they consigned to oblivion. If ever I want to decide what to read next, the answer is right at my hip.

The post my reading list and how it gets that way appeared first on Paul Vitols.

October 21, 2019

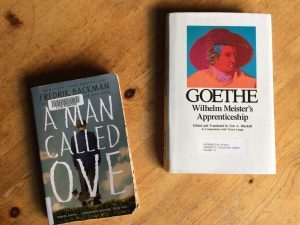

novel vs. novel 2: men with attitude

Back in August I wrote a post in which I compared two random novels that I happened to have read back to back. Well, that was so much fun I’m going to do it again.

How do I happen to choose the fiction I read? The works come to my reading list (a document I keep on my phone) from various sources, which I then read in the order in which they were added, because that’s the kind of person I am. Today’s brace of novels are A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman, published in 2012, and Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, published in 1795–96. The former was recommended to me by an old classmate of mine when I met him at a high-school reunion in 2017; the latter came I remember not how, but probably from some book or article that was talking about Goethe’s views on art. Anyway, Goethe is one of the Great Books authors, and so I have a predisposition to reading his works.

Guy stuff

So: another random juxtaposition, which perhaps might not seem fair to either author. But I think it is fair, just because I did read them back to back, and because I think any work of poetry, of creative writing, of storytelling, can be compared with any other.

Despite their seemingly great differences, there are commonalities between these books. They are both works in translation, for one thing—Ove from the Swedish and Wilhelm from the German. And they are both about men: title characters with strong outlooks on life. Ove is a grumpy 59-year-old widower who is set in his ways; Wilhelm Meister is a young man with a romantic, philosophical nature and a passion for theater. And the two books, in very different ways, are comedies, at least in the most basic sense of having (mostly) happy endings. There are ironies in there, but I don’t want to be a spoiler so I won’t go into that further.

Unlike last time, I finished both these books, which meant that I considered them both to be good enough to be worth reading, and I wound up giving them both 4 stars out of 5 on Goodreads. So I’ve had some pretty happy reading lately.

To give a flavor of these books, I will again present their openings. Let’s look at A Man Called Ove first. Chapter 1 is entitled “A Man Called Ove Buys a Computer That Is Not a Computer”:

Ove is fifty-nine.

He drives a Saab. He’s the kind of man who points at people he doesn’t like the look of, as if they were burglars and his forefinger a policeman’s torch. He stands at the counter of a shop where owners of Japanese cars come to purchase white cables. Ove eyes the sales assistant for a long time before shaking a medium-sized white box at him.

“So this is one of those O-Pads, is it?” he demands.

The assistant, a young man with a single-digit Body Mass Index, looks ill at ease. He visibly struggles to control his urge to snatch the box out of Ove’s hands.

“Yes, exactly. An iPad. Do you think you could stop shaking it like that . . . ?”

Ove gives the box a skeptical glance, as if it’s a highly dubious sort of box, a box that rides a scooter and wears tracksuit trousers and just called Ove “my friend” before offering to sell him a watch.

Here we have comic writing that is quite effective. By the end of the third sentence we already have a strong impression of the character; indeed we may feel that we already know him as much as we want to. In most stories he would be a minor character whose grumpiness raises a few chuckles as we pass by, following other characters who are more engaging and likable, but here he has the starring role. What gives?

Ove’s grumpiness is offset by the comic detachment of the narrator. The author shows himself to creative in coming up with unexpected and illuminating figures of speech, such as the simile about the policeman’s torch, or “the owners of Japanese cars,” which is the figure known as antonomasia, the use of an epithet instead of a proper name. This points back to the second sentence, contrasting these people with the Saab-driving, and thus patriotic, Ove. The sales assistant is described as having “a single-digit Body Mass Index,” an instance of hyperbole, as well as, perhaps, prosopographia, the lively description of a person. All of these make the book’s opening vivid and suffused with the main character’s attitude.

Now let’s look at the opening of Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship:

The play lasted for a very long time. Old Barbara went to the window several times to see if the coaches had already started leaving the theater. She was waiting for Mariane, her pretty mistress who was that night delighting the audience as a young officer in the epilogue—waiting for her with more impatience than usual, when she merely had a simple supper ready. For this time a surprise package had come in the mail from a wealthy young merchant named Norberg, to show that even when he was away, he was still thinking of his beloved. A trusty servant, companion, adviser, go-between and housekeeper, Barbara had every right to open the package. And this evening she could not resist, for the favors of this generous lover meant even more to her than they did to Mariane. To her great delight she found in the package not only fine muslin and elegant ribbons for Mariane, but for herself a length of cotton material, scarves and a roll of coins. She thought of the absent Norberg with great affection and gratitude, and eagerly resolved to praise him to Mariane, to remind her of what she owed him, and of his hopes and expectations that she would be faithful to him.

Interestingly, this story about a young man opens on a scene featuring women, specifically the servant of an actress. The narration is much less immediate than that of the modern A Man Called Ove; where Ove’s narrator steeps us in the hero’s view of the world, even if it is at a comic remove, here the narrator is disinterestedly telling us about the action. There may be a touch of irony—when the narrator says “Barbara had every right to open the package,” he is certainly expressing Barbara’s point of view, but it’s not quite clear whether he is expressing his own as well—but overall there is a feeling of calm detachment.

These books are comedies, and one of the hallmarks of comedy, as I learned by reading Edith Hamilton’s excellent book The Roman Way, is that the story portrays typical situations, for people only laugh at what they recognize. This is what makes comedy especially useful for historians, including ancient historians such as herself. Here we have the modern grumpy Swede Ove at a loss in a computer store, a situation typical of our current tech-obsessed society. But in 1795 Germany, the typical situation portrayed is that of an attractive actress, her sugar-daddy admirer, and her go-between personal maid who has her own stake in the relationship. In Goethe’s day this situation would have been familiar to readers and would have set up a number of expectations based on that familiarity.

But despite certain similarities, these two stories are as different in their respective missions as they are in their narrative styles. A Man Called Ove is a character study, the story of a man who is pulled from a living death back to engagement with life by the caring people around him. Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, though also concerned with its hero’s character, is much more a novel of ideas. It addresses the issues of education and vocation in the widest sense, and often depicts thoughtful, educated characters discussing and disputing points in these subjects. Based in part on these interactions, Wilhelm switches vocations a couple of times in the course of the story, wavering between his passion for art and his sense of responsibility to the bourgeois world that produced him. His path is shaped too by his overwhelming attraction to certain women. His “apprenticeship” is long and has many twists and turns.

These books are both comedies, but in most respects are as different as can be. To be honest, I had some credibility problems with them both. In Ove‘s case, I found many of the characters to be too cartoonish and unbelievable. Too many people seem to warm up to Ove, who really is a prickly customer. The developments are also rather predictable.

In Wilhelm‘s case, there are too many strange coincidences and mysteries. While Goethe is a master of creating believable surprises, truly unexpected and lifelike twists, he also brings in far-fetched and incredible developments. The story as a whole cannot really be called believable, even extending the author all the credit you can. But Goethe can be funny, although in a completely different manner than Backman. I laughed out loud at some of Wilhelm’s passionately delivered criticisms of actors and their lifestyle. I’m sure his observations would apply just as much today as they did then.

Bottom line: I liked these books quite well. What’s next on my reading list? Watch this space.

View all my reviews on Goodreads

Help me create more by becoming one of my Patreon patrons. If you’d like to support my work without spending money, I have just the page for you.

The post novel vs. novel 2: men with attitude appeared first on Paul Vitols.

September 25, 2019

appointment at Dendera

I continue to work on the climax of The Age of Pisces. I think I have the main climax pretty much roughed in, and I’m focusing on a subplot climax for the same character. In the process of working on this, I discover how much I don’t know about my story or its characters, which shocks me, considering how long I’ve been working on this thing. But that’s reality, and the only cure for ignorance is to seek truth—or at least to seek information.

Her biographies were written by the victors

This search takes twists and turns as I reach for materials from which to build my story. Years ago I realized that Cleopatra—yes, that Cleopatra, Cleopatra VII Philopator, final monarch of the Ptolemaic empire of Egypt—was a character in my story. I thought that she was a minor character for me, though, so I didn’t spend much effort on learning about her. When I visited Chapters bookstore at Park Royal in November 2008, and saw Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend by Joann Fletcher on a shelf there, I felt that the relatively steep new-book price (the Canadian equivalent of the preprinted cover price of £12.99) was too high to justify the expense, and left the book behind. But when I got home I had qualms about my decision, and when my wife asked me a few days later whether there was anything she could pick up for me while she visited Park Royal, I said yes, and that day I took possession of a copy of Joann Fletcher’s book.

I read about two thirds of it at the time—as far in Cleopatra’s life as I saw my story taking me. I enjoyed reading it, appreciating the author’s well-informed and passionate style and her wish to push back against the negativity associated with Cleopatra from a long line of more or less hostile histories. The book is filled with many interesting details and asides, and Fletcher makes bold to fill in gaps in the record with plausible conjectures and shrewd inferences, all of which I really liked. But as other, more pressing research questions came to occupy me I shelved the book in the ancient-history section of my office bookcase, where it rested until about 2 weeks ago, when I discovered that Cleopatra was becoming a bigger deal in my story.

Now I’ve pressed on almost to the end; indeed, I’m all the way to the epilogue, with only 20 pages left to read—but the book is again being pushed aside by other more urgent reading! Thus my reading life. Nonetheless, I intend to finish it this time, for even though Cleopatra’s death in 30 BC is well after the end of what I’m calling Season 1 of The Age of Pisces, the events surrounding that end are key in forming my own theory of Cleopatra’s motives and actions in life.

Is it too much of a spoiler to say that in my story Cleopatra forms the intention of becoming the queen of the world, originally with Julius Caesar as her coruler and later, after Caesar’s death in 44 BC, with Mark Antony? There are grounds for believing, as Joann Fletcher suggests, that Cleopatra saw herself as a direct descendant of Alexander the Great, the first and only emperor to rule over both West and East (as far as was then known), and that her ambition was to restore his domain with the help of Roman power.

I believe further that Cleopatra saw the birth of this new world empire as coinciding with the imminent astrological Age of Pisces, which was to dawn in the latter half of the first century BC. Cleopatra and her son by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, are prominent in the artwork at the temple of Hathor at Dendera, 60 km north of Luxor, which is famous for the zodiac carved there on the ceiling of the Osiris chapel. After the Alexandrian War of 47 BC, in which Julius Caesar defeated the forces of Cleopatra’s little brother Ptolemy XIII and installed her on the throne of Egypt, Caesar famously took a prolonged voyage up the Nile with his new mistress the young queen—a leisurely trip that puzzled his countrymen, since he was still embroiled in a civil war for control of the Roman Empire. It’s not recorded exactly where they went or what they did, but I believe they traveled to Dendera, and there conceived their world empire for the new Age of Pisces (their son Caesarion had already been conceived, and would be born about 3 months later).

When Caesar was assassinated, his will made the unusual provision of posthumously adopting Octavian as his son. But Caesar already had a son: Caesarion in Egypt, thought to be a descendant of Alexander the Great on his mother’s side and of Venus on his father’s, for the Julii regarded themselves as the offspring of that goddess. When the forces of Octavian finally defeated Antony and Cleopatra in 31 BC, he had to make sure that the line of Caesar was clear and single—and passed only through himself. Caesarion, aged 17, was accordingly executed. (In this he was unlike his mother, whom Octavian wanted preserved alive to be displayed in his triumph in Rome. To prevent this humiliation, Cleopatra killed herself, as did her personal maids, but not, Fletcher surmises, with an asp, as ancient writers supposed, but probably with poisoned hairpins.)

This was the real birth of the emperor who would come to be called Caesar Augustus, and of the Roman Empire itself, properly so called. In a certain sense Cleopatra could be called its mother, who died in childbirth. Her vision of a cosmic, world-spanning empire that embraced a divine mission would happen in an unexpected way: by the flowering in Rome of a strange new religion from the East.

View all my book reviews on Goodreads

Help me create more by becoming one of my Patreon patrons. If you’d like to support my work without spending money, I have just the page for you.

The post appointment at Dendera appeared first on Paul Vitols.