Sarah Zama's Blog, page 63

April 28, 2016

Thursday Quotables – The Sorceress and the Skull

Dante walked home through the dense fog and sensed someone followed. Yet, each time he slowed and looked back, he saw and heard nothing suspicious. Eyes and ears on full alert, he hesitate at the front steps of his house. A persistent meowing came from the front door. Dante went to the burnt sienna, yellow-eyed cat sitting still on its haunches stiff as a sentinel. It reminded him of Egyptian cat-goddess statuettes.

Dante bent and petted the cat, which rewarded him with relentless purring. The cat arched its back under his hand, and he discovered its gender was female. “Cat, I can use some company, so whoever you are, you may stay the night, or longer if you wish.”

Dante opened the door, and the cat rushed inside ahead of him as if she knew where to go. He switched on the lights, grateful his father’s partners had notified PG&E and the telephone company to connect their services. Dante next went into the library, where the cat observed him from the mantle above the cold fireplace.

“If you intend to stay, I must give you a name. No idea what you were called before.”

What intrigued me the most about this story when I first learned about it it’s the same thing I appreciated the most when I read it: its very strong ‘occult’ feeling. There are a lot of classic elements of the story of the occult here: Nostradamus’s prophecies, Egyptians cats, sentient gargoyle statuettes, seers, ancient Byzantium lineage, secret Masonic-like societies. Add a 1940s San Francisco setting and it makes for a very definite atmosphere.

What intrigued me the most about this story when I first learned about it it’s the same thing I appreciated the most when I read it: its very strong ‘occult’ feeling. There are a lot of classic elements of the story of the occult here: Nostradamus’s prophecies, Egyptians cats, sentient gargoyle statuettes, seers, ancient Byzantium lineage, secret Masonic-like societies. Add a 1940s San Francisco setting and it makes for a very definite atmosphere.

The plot is packed full of events, there are many characters and it looks like everyone is up to something. Although Nostradamus’s descendant and powerful seer in the making Michele is clearly the centre of the story, the character I liked the most and the one I related to the best is Marco Dante, a veteran of the Great War whose face has been disfigured on the battlefield. Now dismissed from the army, he has turned a painter of great success and after he meets Michele his paintings become kind of mystic. He’s a very caring character, and that’s what I like about him.

So this is an enjoyable story, but I think it could have been even more so if the narrative style had been more direct. The author relies a lot on recounting the story rather than letting it play in front of the reader’s eye, and this didn’t allow for a lot of involvement, in my opinion. But in spite of this, the eventful plot makes for an easy read.

——————————

In addition to be part of the Thursday Quotables meme at Bookshelf Fantasies, which I often take part to, this post is also part of the Book Tour for the launch of the book

————————————————————————–

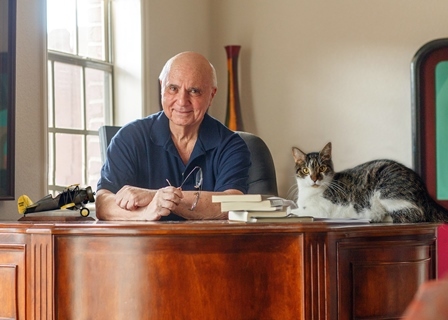

Donald Michael Platt

Donald Michael Platt is an award wining author of five published novels: “Rocamora,”an International Book Awards Finalist, and its sequel “House of Rocamora” set in 17th century Spain and Amsterdam during their Golden Ages. “Close to the Sun,” a WWII novel about USAAF and Luftwaffe fighter aces has garnered three Indie Book Award Finalist Awards. The Historical Novel Society named his novel “Bodo the Apostate” an Editor’s Choice title, calling it “a masterfully-controlled narrative” of the Carolingian Empire. “A Gathering of Vultures,” a contemporary horror novel set in Florianópolis, Brazil, was also selected as an Indie Book Award Finalist in Horror.

Donald Michael Platt is an award wining author of five published novels: “Rocamora,”an International Book Awards Finalist, and its sequel “House of Rocamora” set in 17th century Spain and Amsterdam during their Golden Ages. “Close to the Sun,” a WWII novel about USAAF and Luftwaffe fighter aces has garnered three Indie Book Award Finalist Awards. The Historical Novel Society named his novel “Bodo the Apostate” an Editor’s Choice title, calling it “a masterfully-controlled narrative” of the Carolingian Empire. “A Gathering of Vultures,” a contemporary horror novel set in Florianópolis, Brazil, was also selected as an Indie Book Award Finalist in Horror.

Donald and his wife Ellen currently reside in Winter Haven Florida along with his cat, Bodo, a loquacious tyrant.

website | twitter | facebook

The post Thursday Quotables – The Sorceress and the Skull appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 27, 2016

XX Century (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - XX Century #AtoZChallenge #jazz the sound of a new era

Click To Tweet

Detractors and supporters of jazz argued on many aspects of the music and on its value as a form of art, but they all agreed on one thing: its popularity was tightly linked to the changes in society that had started after WWI. Whether these changes were perceived as positive or negative depended largely on the critic being modernist or traditionalist.

In any case, jazz was often credited as expressing a break with the past and the introduction of a new time and speed that took place after the Great War.

This new rhythm was the expression of life in the city as opposed to life in rural areas. It was the rhythm of machines, the sound of more modern times. The new rhythms were not simply faster. The irregularity and syncopation also gave a sense of hurry, the sense of the unpredictability this new life seemed to bring about.

Many artists of the 1920s caught this sense of constant shifting and changing, a sense of insecurity. The changing conception of time was central to the 1920s sensibility in many fields, and art in particular. This ‘lost’ generation of artists despaired about their fate. They felt confused in the transition from valued already fixed to values that had to be created, uncertain in that diffuse insecurity.

Many artists of the 1920s caught this sense of constant shifting and changing, a sense of insecurity. The changing conception of time was central to the 1920s sensibility in many fields, and art in particular. This ‘lost’ generation of artists despaired about their fate. They felt confused in the transition from valued already fixed to values that had to be created, uncertain in that diffuse insecurity.

Jazz was already firmly placed in this feeling. It was very often associated with the transition form rural to urban life, from slow to faster times, from before to after, and so it provided a strong symbol for that transition to new values. Jazz became not just a language of music but also a language of visual arts and of storytelling. In the Jazz Age, it was a pervasive presence.

Jazz was the language of this generation. It was an experience that conveyed change – not merely an aspect of a culture affected by change. In its syncopated, totally new rhythms, it lost generation found itself.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

RESORCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post XX Century (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 26, 2016

White Audience (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - White Audience #AtoZChallenge In the #1920s white and black #jazz were never the…

Click To Tweet

The history of jazz in the 1920s always ran on two separate tracks: black jazz on the one hand, white jazz on the other, and really very seldom they crossed paths.

These were almost two separate forms of art, happening in very different environments and following very different performing practices.

Black jazz was much more intuitive, was often more lively and relied on call-and-response both among musicians and between performers and audience.

White jazz sought more symphonic orchestrations, tended to be more mellow and less syncopated, and the call-and-response especially between performers and audience was less prominent.

Nick LaRocca

Nick LaRoccaIn many respects, it could be argued that white jazz in the 1920s was less revolutionary than black jazz, and still it was far more popular and received a lot more recognition.

One of the reasons is that the first instrumental recordings specifically labelled ‘jazz’ featured the Original Dixieland Jass Band, a white band from New Orleans lead by Nick LaRocca. This record was a huge success, it sold over one million copies and made jazz known to a wide public, even the one who didn’t frequented nightclubs and speakeasies.

Paul Whiteman

Paul WhitemanAlthough subsequently many black jazzmen recorded their music, white musicians had always an easier access to recording.

One of these musicians, Paul Whiteman, is probably the most popular of his time. In the 1920s, he was the King of Jazz in most people’s mind. Besides, a large part of the public didn’t’ even have access to black-and-tan and black clubs, where most black musicians were more popular. Slumming was in vogue, but only a small amount of the public actually did it. So, between the limited access to authentic black jazz and the actual attempt at appropriation that white musicians and especially white critics were pursuing, a large part of the 1920s public were never aware that jazz had originated in the black community and was still prominently an African American form of art.

Some white performers perfected what became known as ‘nut jazz’. They consciously distorted blue notes and turned them into grossly exaggerated groans, growls, moans and laugh.

On the other side of the spectrum, other performers adopted the opposite strategy and ‘diluted’ or ‘refined’ blue notes by de-emphasising them. Because this kind of jazz was what was more often recorded (because it was played prominently by whites), it was also what became more popular, which marginalised most black and some white musicians who remained wedded to participatory and improvisational jazz performance.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

RESORCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

PBD Official Site – The Devil’s Music: 1920s jazz

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post White Audience (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 25, 2016

Vaudeville (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Vaudeville #AtoZChallenge Between the minstrel shows and the new #jazz

Click To Tweet

Vaudeville is a form of entertainment that flourished in the United States from the 1880s to the 1930s, though its roots go further back, into one of the first forms of musical in America, the minstrel show.

Beginning in 1828, Thomas D. Rice, a white man, presented a show where only black characters were featured, the most popular of which was Jim Crow, the caricature of a lame black man who would sing and dance. These shows relied heavily on racial and ethnic stereotypes to produce what was then perceived as a comic show.

Although all characters were black, very few African Americans ever performed in minstrel shows before the end of the Civil War. Performers were white men in blackface, which they achieved by rubbing burn cork on their faces. No woman ever performed in minstrel shows, all female characters were performed by men.

Minstrel show had a three parts structure:

First section: included comic patter among the actors, songs and comic skits.

Olio: The second section consisted of specialty acts: songs, dances and comic speeches and dialogue. Because this part was less schematic and leaned more heavily on the actual ability of the performers, olios of different companies could vary greatly in regard to quality.

Afterpiece: the third act was a short, farsical play on antebellum plantation life, usually featuring the popular characters Jim Crow and/or Zip Coon.

Bert Williams

Bert WilliamsBecause the olio was the part of the show that allowed more artistic freedom and variety, by the end of the Civil War, this was the part of the show most popular with the audience, so it had kept growing in length, eating away time on the other two sections.

At a certain point in the last part of the 1800s, the olio took up a life of its own. That’s how vaudeville was born.

By the turn of the century, minstrelsy had all but died out and vaudeville had become the most popular American entertainment.

But another source had a defining influence on the vaudeville show: burlesque.

Burlesque had began with a series of sketches parodying current social and artistic trends. Soon it turned into a show where scantily clad women who were required little skill in dancing and singing would parody the soubrettes of ‘higher’ form of theatre.

Vaudeville consisted of songs, dances and comic routines each of about three minutes in length, and like minstrelsy, it was a touring art form. Theatres were organised in circuits specialised in white or black entertainment, and ‘big time’ or ‘small time’ entertainment. Producers were normally centred in New York City and owned the entire circuit on which they would send headliners and supporting entertainers.

The tradition of minstrelsy and vaudeville would cling to jazz all though the 1920s… and it wasn’t a good one. Many jazzmen and especially blueswomen, formed and found their fame on these circuits. Because of the reliance of both vaudeville and especially minstrelsy on racial stereotypes, black intellectuals didn’t see these performing arts very favourably, while white critics considered them to belong to a lower kind of art. During the 1920s, jazz and blues never shed this stigma off of them.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

RESORCES

Virginia Edu – Vaudeville

American Masters – About Vaudeville

Musicals 101 – Vaudeville (part IV)

Geneseo Edu – Musical Theatre (part I)

Scaruffi.com – A bried history of blues music

Madame Pickwick – Vaudeville: American culture is performance

YouTube – Blacks and Vaudeville (PBS documentary)

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Vaudeville (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 24, 2016

Union (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Union #AtoZChallenge In the #1920s the first attempts at unionising jazz musicians

Click To Tweet

The 1910s and 1920s was the time when the first timid attempts to unionise workers took place. Unions tried to unite workers so to give them the power of numbers against employers, but they also tried to put rules on workers’ behaviour. And because they enforced rules and standardisation, unions also tried to apply sanctions when rules were not met.

These first attempts had very varied results and generally quite a hard time. This was made worst by the fact that most unions were segregated, so many workers (especially African Americans) refused to enter unions on this ground.

The American Federation of Musicians (the musicians’ union) was organised in many ‘locals’ designated with a number. Locals had all a very distinctive life based on regional situations.

Two of the most important were located in the two foremost cities where jazz was played.

Duke Ellington

Duke EllingtonNew York City – Local 802

New York Local 802 was quite unique in that it exhibited a great degree of tolerance to internal division. A great variety of ethnic interests and groups coexisted more or less peacefully. There were Irish and Jewish organisations, but also flutist organisations. Ethnic minorities and instrumental minorities could retain their identity and voice and still belong to the union.

This allowed to individual musicians to sometimes maintain separate commitments while still being part of the union.

Chicago – Local 208

In Chicago, New Orleans musicians, who were a majority of jazzmen, seemed to be largely uninterested in the union. Despite the union guaranteed higher incomes, black performers worked in a community where segregation greatly circumscribed employment and attitudes toward black entertainment.

The management of Local 208 was also heavily influence by the music ideals of a Defender columnist, Dave Peyton. He upheld an idea of proper music that was more adherent to the European classic standard and although he was not a union man, his ideas appear to have had great influence on the Local’s attitude toward music. The union had authority in finding jobs, so jazzmen ended up being penalised on this ground. This was probably why many Chicago jazzmen never cared to join the union.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

RESORCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

Associated Musicians of Greater New York – Local 802 at the time of the Harlem Renaissance

Black Past – Race, Gender, Jazz & Local 493: Black Women Musicians in Seattle 1920-1955

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Union (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 22, 2016

Tempo (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Tempo #AtoZChallenge It was #jazz a new tempo or a new time

Click To Tweet

Early jazz was strongly connected to sensuality. Its fast tempo, its syncopation, brought it a lot of trouble, because in many respects, that rhythm was associated with sensuality.

At the very beginning, jazzmen would perform in brothels, which connected jazz with sexuality from the start. The music itself was syncopated and meant to be danced with transport and freedom. In fact, jazz became so popular because of the popularity of dancing, which, by the way, happened in questionable environments – like speakeasies – where different forms of rules were routinely broken. It was quite clear that jazz was something disreputable that nice people wouldn’t want to be involved with.

Most critics of the 1920s exhorted listeners to resist the devil or wicked power jazz could exert on human behaviour through its fast, entrancing tempo. They believed that this music reduced moral restrains and encouraged sexual permissiveness and a state of mind similar to alcoholic intoxication.

It isn’t surprising then that some 1920s reformers hoped to pass a legislation that – similar to the prohibition of alcohol – would control, limit and hopefully stop the flow of jazz.

It isn’t surprising then that some 1920s reformers hoped to pass a legislation that – similar to the prohibition of alcohol – would control, limit and hopefully stop the flow of jazz.

The dances themselves were often criticised, if not cried against. Most of the Jazz Age dances were meant to be danced in couple, most were meant to have the partners’ bodies touch and rub against each other. Most of these dances were fast and exhilarating.

Raids against dance places weren’t uncommon, as were outcries on newspapers.

What critics never thought about wondering was why people, especially youths, liked these dances. Why they sought the exhilaration of the dance itself and the shiver of the prohibited.

These youths were the same who wanted to break with the past and with their parents’ values. The same youths that had known war and wanted to forget it.

Jazz was their language. The language of their body and their minds. The tempo of this music was their tempo, which was widely different from that of any previous generation. Jazz music broke the rules and sought ever new ways to express the present and the future. Jazz tempo was the tempo of a new era and a new world.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

RESORCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Tempo (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 21, 2016

Sensuality (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Sensuality #AtoZChallenge Blueswomen and the power of stereotypes

Click To Tweet

It isn’t very hard to see why one of the most controversial figures of the Roaring Twenties ended up being the black woman who sang the blues.

The blueswoman gathered in herself most of the controversial issues of the time. She was a modern kind of woman. Like the flapper, she sought her freedom of expression and self determination. She was a black woman subject to the spersonalization of Primitivism, and she was a show business woman, trapped in the new modern consumer society.

It wasn’t an easy balance.

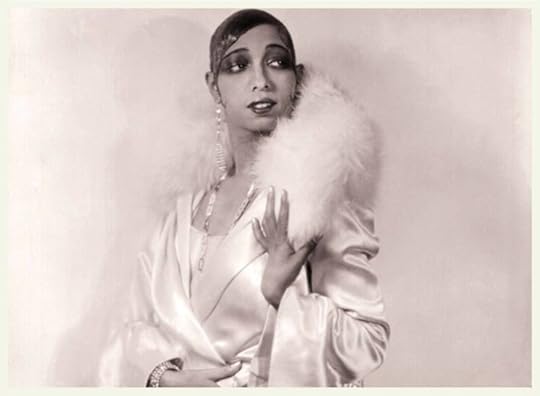

Josephine Baker

Josephine BakerOn the one hand, the blueswoman had the strength and character to create herself. Her talent, ambition and audacity helped her become prominent and visible inside the very competitive show business, and her deep roots in African American tradition asserted her cultural character.

But on the other hand, this alone wouldn’t have been enough. The Twenties liked to celebrate the personality, but also privileged the exotic and the open display of the body and sexuality… and blueswomen certainly didn’t hold back from it.

Although the blueswoman was indeed, partly, her own creation, especially in the shifting of genre and sexual mores discussion, she was also shaped by the strong imagination of the primitivist’s mind. She was a particular manifestation of the New Negro.

Bessie Smith

Bessie SmithThis position made the blueswoman both an actor and a victim of her circumstances, which she fought with every means possible.

In 1920s, Josephine Baker became extremely famous by playing the Primitivism game. She was not opposed to the commodification of the black female body, rather she exploited white eroticization by basing her shows on racial stereotypes.

Ma Rainy, who was famous for her many affairs with both young men and women, sang song – often written by white men – that played on the theme of the sexually aggressive woman, a stereotype that came down to black women from the time of slavery. Black female body as an object, originally in slavery, then in minstrel and vaudeville shows, must be kept in mind when considering how black performers succeeded on national stages.

The greatest power of the sex-race marketplace was its ability to wholly obscure the distinction between real, human black woman and their glamorous, exotic, erotic representations. Blusewomen were aware of this, and if in some respects they simply accepted it in return for fame, in other respects they used that fame to make their voice be heard. Once they had allowed stereotypes to make them visible, they used that visibility to forward a more authentic view of themselves.

Not an easy balance at all.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

RESOURCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

Chapman, Erin D. Prove It on Me – New Negros, sex and popular culture in the 1920s. Oxford University Press, New York, 2012

Westerns Libraries – The Politics of Black Sexuality in Classic Blues (PDF)

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Sensuality (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 20, 2016

Race Records (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Race Records #AtoZChallenge A stunning success of #jazz #AtoZChallenge

Click To Tweet

The 1920s were the golden age of the recording industry. True, it was the dawn of that business, it was still rough and clumsy, but it offered an array of completely new possibilities to make money.

Offerings of recording aimed to a particular audience began when record companies realised there was an untapped market of new immigrants yarning for the sound of home. Catalogues of ethnic records were produced specifically for this market and included re-pressed recordings form Europe and new recording by American immigrants artists. These records were marketed directly to the specific ethnic community and seldom found their way outside of that context.

Harry H. Pace – Founder of Balck Swan Records

Harry H. Pace – Founder of Balck Swan RecordsThe first jazz record specifically labelled as such was recorded in 1917 by the Original Dixieland Jass Band, a white band originally from New Orleans. Not until 1920 black musicians and singers started to be recorded with any regularity. That was the year in which black composer and pianist Perry Bradford championed a young entertainer named Mamie Smith, who recorded a version of Bradford’s Crazy Blues with the General Phonographer’s Company OKeh label. It was a huge success. It sold 75.000 copies the first week in Harlem alone and prompted OKeh Records to launch their own ‘race records’ line, the first ethnic line specifically produced for African Americans.

Soon, other white-owned record companies followed in OKeh’s footsteps and the outstanding success of these records had in African American communities across the nation made it possible for smaller – and often short-lived – black-owned companies to open business. Among these, Black Swan was the most pre-eminent.

Race Records were sold practically only to African Americans and based their appeal to authenticity to a variety of qualities including musical characteristics, performer reputation, the race of performers and even the race of the company employees and owners. In fact the name ‘race records’, that whites might have connected to segregation, probably had a very different meaning for African Americans who in the 1920s were strongly called to upholding the Race pride.

Race records didn’t just offer blues, although that was the main and more popular subject. They also featured sermons, minstrel songs, spirituals and gospel tunes, popular song and some early jazz.

Sales reached 5 million copies a year. Newsboys sold blues records. So did door-to-door salesmen. Pullman porters carried copies south with them and paddled them in whistle shops.

They were hugely popular.

————————————————————————————————————————————–

RESOURCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

Shmoop – Race in blues music history

Encyclopedia Britannica – Race Records

The Library of Congress – African American Performers on Early sound Recordings (1892-1916)

The People History – 1920s Music

PBS – Jazz

CentreStage – Race Records

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Race Records (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 19, 2016

Quotes (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Quotes about jazz #AtoZChallenge Can #jazz be explained with words?

Click To Tweet

But playing with John [Johnny Dodds] was a hard assignment for everyone. There was no outstanding individual in the outfit, everybody had to work in harmony. With a small outfit like that [four men] we either had to work together or we wouldn’t make music

– Baby Dodds (The Baby Dodds Story)

They hear it come out, but they don’t know how it got there. They don’t understand that’s life’s way of talking. You don’t sing to feel better. You sing ’cause that’s a way of understanding life.– Ma Rainey

“A problem is a chance for you to do your best.” ― Duke Ellington #quote #jazz

Click To Tweet

The rhythm persisted, the unfaltering common meter of blues, but the blueness itself, the sorrow, the despair, began to give way to hope– Rudolph Fisher

An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he might choose.– Langston Hughes

If a man isn't faithful to his own individuality, he cannot be loyal to anything - C. McKay #quote

Click To Tweet

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Quotes (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.

April 18, 2016

Primitivism (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz)

JAZZ AGE JAZZ - Primitivism #AtoZChallenge The illusion of a simpler life

Click To Tweet

In the 1920s, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis became very popular even outside of his professional field. This was true especially in the US and may be one of the factors that cause a revival of Primitivism.

In the 1920s, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis became very popular even outside of his professional field. This was true especially in the US and may be one of the factors that cause a revival of Primitivism.

Primitivism argued that emotional repression had become endemic in the Western world and invested ‘primitive’ cultures with ‘uncivilized values’ that could cure this illness and rejuvenate the tired Western society by freeing its more natural desires – particularly sexuality.

Primitivism pre-dated the 1920s. American writers had created many primitive worlds and characters. In these stories, Native Americans and African Americans often played the idealised role of the noble savage or the fearsome barbarian. It was a depiction that had nothing realistic to it. In the light of Primitivism, different cultures were idealized (for good and bad) so to match a particular idea and stereotype, not to actually describe them as they were. They became a vehicle of an ideology, not the portrayal of real people.

Carl Van Vechten

Carl Van VechtenFor this reason, Primitivism never sparkled any true interest in the culture being depicted.

It was mostly a fantasy that often referred back to other ideas important to the artist.

Writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Carl Van Vechten, for example, were noted for their forays into Primitivism. Although keenly interested in the jazz culture, they mostly displayed a more general interest in modernism and supernaturalism than true interest in jazz culture. To them, jazz was a symbol, a metaphor of the life as they experienced it. It never became the experience as it was for many Harlem Renaissance innovators. Authors like Langston Hughes and Claude McKay not only depicted jazz as a significant experience in itself, but they went as far as using jazz as a language for their stories.

Entrepreneurs played the idea of Primitivism to such an extent that the plantation life – or rather the stereotyped ideal of plantation life – haunted black entertainment for a long time. Vaudeville, minstrelsy and other stage performances had prepared white audience to expect a certain kind of stereotype. While this certainly damaged African American culture, it may even have trapped both blacks and whites into roles that were not ‘authentic’ but staged.

Jazz became part of this game.

Claude McKay

Claude McKayThe clubs where jazz was played bore names (The Cotton Club, the Plantation Club, the Alabama Club) that used words geographically separated from North and East and culturally unfamiliar to many patrons. The interior décor also played the idea of a different place, unknown and exotic. Everything was constructed so to suggest a displacement, almost a relocation in a different world, a recognizable fantasy. But structure of clubs didn’t encourage participation, it was rather voyeurism. Patrons assumed they were part of black music and performance, that they had entered that exotic world to enjoy whatever unusual experience it had to offer. They were in fact just viewers watching in from a safe, separate position. Patrons could witness and sometimes act in behaviour that were typically ‘off limits’ in everyday life and this created the illusion that the ‘civilised’ barrier had gone down and one would connect with the other. But that’s exactly what it was: a well orchestrated illusion.

To the larger public, African arts were an ideal of a simpler, more intense, more primeval experience of life. African American performance was a natural extension of this ideal… and closer to home, definitely more accessible. The logic of Primitivism made blackness itself a spectacle which made the adventure of ‘slumming’ very popular. Professional of all entertainment industries sought to harness the new blackness – the New Negro – as a lucrative new business.

————————————————————————————————————————————

RESOURCES

Ogren, Kathy J., The Jazz Revolution. Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989

Chapman, Erin D. Prove It on Me – New Negros, sex and popular culture in the 1920s. Oxford University Press, New York, 2012

Smashwords | Barnes&Nobles | Kobo | iBookStore

And many other stores

The post Primitivism (AtoZ Challenge 2016 – Jazz Age Jazz) appeared first on The Old Shelter.