Ed Gorman's Blog, page 155

July 1, 2012

Changing Hammett stroies

Ed here: Mike Nevins is the Edgar-winning novelist/short-storywriter/biographer/historian whose work with the fiction and life of Cornell Woolrich has been acclaimed as definitive. Here's a small piece of what MIke does so, this a reprint from Mystry-File, one of the truly great sites of all time.

Mike Nevins:

I recently attended a convention in suburban Baltimore but arrived before my hotel room was ready. Luckily there was a bookstore with comfortable chairs in the mall across the street, and I killed some time in the mystery section with “Arson Plus,” the first of Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op stories, originally published in Black Mask for October 1, 1923 and recently reprinted in Otto Penzler’s mammoth Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories.

For decades this was one of the rarest of Hammett tales, revived only by Fred Dannay (in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, August 1951, and in the Queen-edited paperback collection Woman in the Dark, 1951).

Today it’s in the Penzler anthology and a major hardcover Hammett collection (Crime Stories and Other Writings, Library of America 2001) and can also be downloaded from the Web in a few seconds.

The other day I felt an urge to compare the e-text with theEQMM and Library of America versions, and made a discovery that startled but didn’t really surprise me. The Web version I downloaded is identical with Fred’s except for a few changes in punctuation and italicization, but both are quite different from the Library of America text, which uses the version originally published in Black Mask.

Fred believed that every story ever written was too long and therefore tended to trim the tales he reprinted, even those by masters like Hammett. Some of the bits and pieces he cut were perhaps redundant, but he also axed part of the Continental Op’s explanation at the end of the story.

Reprinting “Arson Plus” in 1951, he must have felt a need to update some of the price references to reflect post-World War II inflation. At the very beginning of the original version, the Op offers a cigar to the Sacramento County sheriff, who estimates that it cost “fifteen cents straight.” The Op corrects him, giving the price as two for a quarter. Fred raised these figures to “three for a buck” and ”two bits each” respectively.

He also added a cool ten thousand dollars to the purchase price of a house that in the 1923 version sold for $4,500. Where a Hammett character disposes of $4,000 in Liberty bonds (sold by the government to finance World War I), Fred has him sell $15,000 worth of common or garden variety bonds.

Whenever Hammett refers to an automobile as a “machine,” Fred changes it to “car.” Where three men in a general store are “talking Hiram Johnson,” Fred has them merely “talking.” (Hiram Johnson, as we learn from a note in the Library of America volume, was governor of California between 1911 and 1917 and later served four terms as senator.)

He also unaccountably changes the name of a major character from Handerson to Henderson. A quick check of Fred’s versions of a few other Continental Op stories with the original texts yielded similar results and a clear conclusion: to read Hammett’s tales as they were meant to be read, you have to read them in the Library of America collection. This doesn’t help, of course, with the eight Op stories not collected in that volume, but it’s a start.

In every version of “Arson Plus” the plot is of course the same: a man insures his life for big bucks, assumes another identity, sets fire to the house he bought, and the woman named as beneficiary demands payment.

Did these people really think any insurance company would be fooled for a minute when there were no human remains in the ashes of the destroyed house? Didn’t Hammett with his experience as a PI realize that this plot was ridiculous? Was Fred ever bothered by its silliness?

***11 Authors Who Hated Movie Versions of Their Books

by Stacy Conradt - June 22, 2012 - 10:44 PMStephen King probably made movie buffs cringe

when he said he hated what Stanley Kubrick did to The Shining. “I’d admired Kubrick for a long time and had great expectations for the project, but I was deeply disappointed in the end result. … Kubrick just couldn’t grasp the sheer inhuman evil of The Overlook Hotel. So he looked, instead, for evil in the characters and made the film into a domestic tragedy with only vaguely supernatural overtones. That was the basic flaw: because he couldn’t believe, he couldn’t make the film believable to others.” He was also unhappy with Jack Nicholson’s performance – King wanted it to be clear that Jack Torrance wasn’t crazy until he got to the hotel and felt that Nicholson made the character crazy from the start. With director Mick Garris, King ended up working on another version of The Shining that aired on ABC in 1997.

3. After casting was completed for the movie

version of Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire

she said Tom Cruise was “no more my vampire

Lestat than Edward G.

Robinson is Rhett Butler.” The casting

was “so bizarre,” she said, “it’s almost impossible

to imagine how it’s going to work.” When she

saw the movie, however, she actually loved

Cruise’s portrayal and told him what an

impressive job he had done. She still hasn’t

come around to liking Queen of the Damned,

though, telling her Facebook fans to avoid

seeing the film that “mutilated” her books.

Read the full text here:http://www.mentalfloss.com/blogs/archives/131167#ixzz1zPBumyUg

--brought to you by mental_floss!

June 30, 2012

Look Back In Nastiness

Look Back in Anger by John Osbourne

This is the play that really started the whole Angry Young Men movement that took place in Britain in the 50s and brought us such classic movies as This Sporting Life, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Saturday Night, Sunday Morning (also known as Kitchen Sink cinema). This is the story of a couple and their friend who all live on a small working class flat. The husband, Jimmy, is lively, intelligent and bitter with resentment to the point that he is almost constantly abusive to his upper-class wife (who married him against her parents's wishes). They live with a third friend, Cliff, who is a simpler, calmer soul and puts up with Jimmy's tirades against the upper classes, society in general, Alison, her family, her friends.

This is the play that really started the whole Angry Young Men movement that took place in Britain in the 50s and brought us such classic movies as This Sporting Life, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Saturday Night, Sunday Morning (also known as Kitchen Sink cinema). This is the story of a couple and their friend who all live on a small working class flat. The husband, Jimmy, is lively, intelligent and bitter with resentment to the point that he is almost constantly abusive to his upper-class wife (who married him against her parents's wishes). They live with a third friend, Cliff, who is a simpler, calmer soul and puts up with Jimmy's tirades against the upper classes, society in general, Alison, her family, her friends.As a stand-alone story or theatre piece, I wasn't really sure what to make of it. In context, with my limited knowledge of the period and the books and films that came out of it, I get what is being conveyed here. This play launched a new voice and a new representation of what England was going through at the time and it caused a lot of controversy. But by itself, it did seem just kind of depressing. The guy is such a jerk! I mean, I get his frustration and the shittiness of the system and the culture in Great Britain back then. But he has an attractive wife who irons and makes tea and all he can do is shit on her because her parents are socially uptight. I guess that's just my modern perspective speaking. There is also a strange element where Jimmy is constantly railing against the rich and is a total jerk, but of course gets the hot upper class babe and then gets her friend as well. And once he gets them, all they do is iron and make tea and try and understand and tolerate why he is treating them like shit all the time. The 50's - they were bugging.Posted by OlmanFeelyus at 3:32 PM

June 28, 2012

Classic Hollywood Quotes from Actors - Dean Brierly

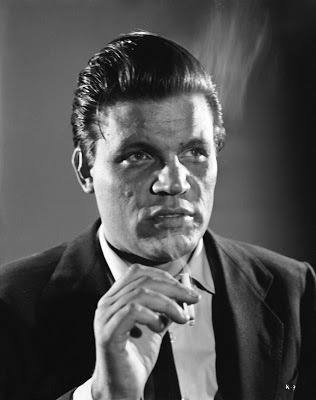

A beautiful mug.

A beautiful mug.“With this kisser, I knew early in the game I wasn’t going to make the world forget Clark Gable.”

Ed here: Dean Brierly always does a great job with his movie article. This is an especially good one. To read all of it go here: http://classichollywoodquotes.blogspo...

Joseph Cotten (1905-1994)

Talented beyond a shadow of doubt.

Talented beyond a shadow of doubt.“Orson Welles lists Citizen Kane as his best film, Alfred Hitchcock opts for Shadow of a Doubt, and Sir Carol Reed chose The Third Man — and I’m in all of them.”

June 27, 2012

Forgotten Books:American Cinema by Andrew Sarris

Posted by R. Emmet Sweeney on June 26, 2012 TCM MOVIE MORLOCKS

Posted by R. Emmet Sweeney on June 26, 2012 TCM MOVIE MORLOCKSThe influence of Andrew Sarris’ film crticism has become so omnipresent it is now invisible, part of the received wisdom of how we approach and watch movies. This has only become clearer after his death last week at the age of 83. You can see his mark in the marketing of the upcoming “Hitchcock Masterpiece” Blu-Ray collection from Universal, and in every movie review that even mentions the name of the director. The auteur theory will be his legacy, regardless of how often it is misinterpreted as some kind of iron law rather than the policy of “perpetual revaluation” that he proposed it as. Enough has been written about auteurism though, and not enough about the constant sense of discovery in reading his seductively winding prose. He approached films like an explorer, traveling down a multitude of paths, be it historical, stylistic or even personal, searching methodically for flashes of insight or originality, whether from the director or any of the film’s collaborative artists. His sentences would gather long strings of actors, colors and themes, as list-happy as in The American Cinema, seemingly sussing out his opinion along the way – a perambulating, open-air kind of criticism where interruption, digression and contradiction are welcome.

Ed here: I'm letting Mr. Sweeny do the heavy lifting here so I can get to some illuminating quotes about Andrew Sarris. As I've written before I wasn't alone in finding some of Sarris' opinions bizarre. He never did find much worht inthe films of Billy Wilder to name just one his failings. I always wondered if Sarris had been influenced by all the bad personal press Wilder got. He was certainly an arrogant prick no doubt about it but if that's the measure of worth half the directors in Hwood would be out of work. Come to think of it that might not be a bad idea. No Michael Bey sounds pretty good to me.But I still remember the joy I felt reading America Cinema for the first time back in college. Here were the directors and the movies I'd grown up with that reviewers paid so little attention to. Crime and suspense and westerns, too, and even some of the B comedies. Sarris not only wrote about them, he exalted them and had little good to say about many of the big stuffy star-driven A movies that got all the attention. So he was always my hero and never less though as the years went by I disagreed with him more and more. I felt sorry for him when Pauline Kael became the critic of choice for intellectuals and psuedo-intellectuals alike. Kael was good but she also knew how to market herself. She was four-inch heels to Sarris' Hush Puppy loafers.

With the death last night of Nora Ephron, two major players in two major eras of film have passed on. Botn Andrew Sarris and Nora Ephron gave me many hours of pleasure and I thank them for it.

Here's a little more from Mr. Sweeny and friends. For the whole TCM Movie Morlocks article go here: http://moviemorlocks.com/2012/06/26/a...

Guest Selections of Sarris’ work

Tom Gunning, A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, Department of Art History, Department of Cinema and Media Studies

Entry on Ernst Lubitsch (Pantheon), The American Cinema:

For Lubitsch, it was sufficient to say that Hitler had bad manners, and no evil was then inconceivable.

Besides showing how concise and precise he could be, it shows Sarris’ ultimate values. In an era when it was claimed films were valuable only if they had Big Ideas (e.g.. Ingmar Bergman) or made Big Statements (e.g. Stanley Kramer), Sarris upheld film style, not simply as a decorative function, but as the true means of expressing a judgement on the world and the people in it. He showed that the great directors of American cinema were great because they had style. Sarris had style. -Tom Gunning

***

Adrian Martin, writer, film critic, teacher

Q&A at the University of Washington, 1987 (transcription at Film Comment):

People talk about Platoon being a great war film. A great war film is Madame de… – the Stendhalian battle of love.

***

Miriam Bale, editor of Joan’s Digest, freelance  critic and programmer

critic and programmer

Review of Robert Aldrich’s …All the Marbles (Village Voice, 1981):

I cannot explain my feelings exactly, but when I left that theater of gutter trash, The National Theater, after a showing of …All the Marbles, I felt cleansed, exhilarated, almost sanctified.

***

Michael J. Anderson, Ph.D. candidate at Yale University, proprietor of the blog Tativille

Entry on John Ford (Pantheon), The American Cinema:

A Ford film, particularly a late Ford film, is more than its story and characterizations; it is also the director’s attitude toward his milieu and its codes of conduct. There is a fantastic sequence in The Searchers involving a brash frontier character played by Ward Bond. Bond is drinking some coffee in a standing-up position before going out to hunt some Comanches. He glances toward one of the bedrooms, and notices the woman of the house tenderly caressing the Army uniform of her husband’s brother. Ford cuts back to a full-faced shot of Bond drinking his coffee, his eyes tactfully averted from the intimate scene he has witnessed. Nothing on earth would ever force this man to reveal what he had seen. There is a deep, subtle chivalry at work here, and in most of Ford’s films, but its never obtrusive enough to interfere with the flow of the narrative. The delicacy of emotion expressed here in three quick shots, perfectly cut, framed and distanced, would completely escape the dulled perception of our more literary-minded critics even if they designed to consider a despised genre like the Western. The economy of expression that Ford has achieved in fifty years of film-making constitutes the beauty of his style. If it had taken any longer than three shots and a few seconds to establish this insight into the Bond character, the point would not be worth making. Ford would be false to the manners of a time and a place bounded by the rigorous necessity of survival.

***

Gina Telaroli, filmmaker and video archivist

Gina Telaroli, filmmaker and video archivist

Review of Psycho (Village Voice, August 11, 1960):

Psycho should be seen at least three times by any discerning film-goer, the first time for the sheer terror of the experience, and on this occasion I fully agree with Hitchcock that only a congenital spoilsport would reveal the plot; the second time for the macabre comedy inherent in the conception of the film; and the third for all the hidden meanings and symbols lurking beneath the surface of the first American movie since “Touch of Evil” to stand in the same creative rank as the great European films.

A wonderful riff on the importance and joys of repeat viewings, with my favorite movie as the subject. -Gina Telaroli

***

C. Mason Wells, IFC Center

Entry on Buster Keaton (Pantheon), The American Cinema:

The difference between Keaton and Chaplin is the difference between poise and poetry, between the aristocrat and the tramp, between adaptability and dislocation, between the function of things and the meaning of things, between eccentricity and mysticism, between man as machine and man as angel, between the girl as a convention and the girl as an ideal, between the centripetal and the centrifugal tendencies of slapstick.

***

Brynn White, film researcher and writer

Review of Marnie (Village Voice, July 9, 1964):

Eisenstein may be spinach, pure iron for aesthetic corpuscles, and Dreyer high protein for the soul, but Hitchcock has always been pure carbohydrate for the palate

June 26, 2012

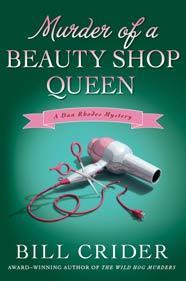

New Books: Murder of A Beauty Shop Queen by Bill Crider

As much as I'm a child of books, movies and comic books, I am also a child of radio. Growing up I probably heard several hundred hours of radio shows of all types from adventure to suspense to western to comedy to even a few soap opera (when my Mom had them on).

Most of the shows had one thing in common. They created worlds for me to inhabit with my imagination. I loved living in those worlds. Sergeant Preston of The Mounties, The Shadow, Superman and the comedies. They were y favorites. The Great Gildersleeve, Fibber McGee and Molly and best of all Jack Benny--I loved being in Benny's household with all his goofy friends, listening to him lose all most if not all of his duel of wits with Rochester, trying to understand the scatterbrain dialogue of Dennis Day--and going down to the vault in the basement. I loved the sound effects. The vault seemed to be a mile deep. I painted it with cobwebs and treacherous, lapping water with the stone steps clinging to the wall. And I couldn't wait to hear the vault itself screeching open.

I mention all this by saying that when I read a certain kind of mystery I want it to give me a world I can inhabit the same way--only this time the author does all the heavy lifting. He or she paints all the pictures for me.

Clearview, Texas is one of my favorite worlds to visit because Bill Crider and his Sheriff Rhodes make it so much fun while giving it real depth by quietly noting, generally with amused compassion, some of the foibles being human entails.

In Murder of a Beauty Shop Queen Rhodes--while simultaneously dealing with a goat who is in a bad mood and a thief who can't be accused of great aspirations--tries to unravel the murder of a fetching young thing whose day job was working at The Beauty Shack but whose night time job appeared to be getting to know an impressive number of men.

In addition to his skills with characterization and milieu, Crider is a master plotter of fair clue mysteries. I say this with abiding envy. One of the many reasons I enjoy and admire his work so much is that I always pick up a few pointers when I read his books and stories..

A final point. He show Yankees a Texas we rarely see or hear or read about. An average small town with average small town people. Decent, hard working people with all the mixed good and bad most of us have, making their way through lives that few outside their circle of friends and coworkers pay much attention to. Crider makes them interesting and entertaining and memorable. No small feat. And he does it with skill and grace.

June 25, 2012

Joseph Lewis

Most evaluations of Lewis' career speculate what he would have done with A picture budgets. He ended up doing a lot of TV work. He made a good deal of money but presumably wasn't as satisfied with his Bonanza stories as he was with his more personal work. He started in westerns and finished in westerns.

As for what he would have done with A-picture money...who knows. But there's at least a chance that he was most comfortable working with the money he was given. Hard to imagine that pictures as gritty as Gun Crazy and The Big Combo could have been shot the way he wanted them to be in an A-picture environment. These are films that took no prisoners and Hwood, especially in those days, wasn't real keen on grim movies.

I found this evaluation of Lewis by David Thomson, my favorite film critic:

"There is no point in overpraising Lewis. The limitations of the B picture lean on all his films. But the plunder he came away with is astonishing and - here is the rub - more durable than the output of many better-known directors...Joseph Lewis never had the chance to discover whether he was an "artist," but - like Edgar Ulmer and Budd Boetticher - he has made better films than Fred Zinnemann, John Frankenheimer, or John Schlesinger." - David Thomson (The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, 2002)

June 24, 2012

John Fraser: John McPartland

McPartland deserves the attention. He seems rather to have slipped through the critical net, maybe

because he didn't deal in the to my mind rather cliched noir depressiveness,

with the inevitable failure of love. I'm glad you yourself have been onto

him.

He can really SCARE you, can't he?

Best,

John.

John Fraser has a very readable and wise website devited to books of various kinds. http://www.jottings.ca/john/thriller_...

John McPartland by John Fraser

John McPartland

She was the kind of woman a man noticed, mostly because of her eyes. Dark, almost black pools, they had a warmth that I felt could turn to fire. She had turned her head, looking over the shoulder of the man she was with, and we looked at each other. The third or fourth time it happened he noticed it and I paid some attention to what he was like.

He was a type. You find guys like him driving ten-wheeler transport trucks, or flying, or sometimes as chief petty officers in the Navy, on a sub or a destroyer. Square-built, tough tanned skin, big hands with knuckles that are chunks of stone.The type—what makes him recognizable as a wanderer, a fighter, sometimes a killer—shows in his face.

Big white teeth, yellow a little from cigarettes like his fingers, and he smiles with his teeth closed, talking through them when he’s angry. A thin line of short black hairs for a mustache, sideburns of curling hair, hair black and curly, a face that is rough and yet young, and it won’t change much if he lives to be fifty. The eyes are fierce, amused, hard.

It’s a special breed of man, and the breed are men. Maybe a mixture of German, Irish, French-Canadian, with a streak of Comanche, Ute, or Cheyenne in there about three generations back. You meet men like this one in the truck-stop cafés along U.S. 40, with the diesels drumming outside; or you meet them walking toward the plane on the airstrip; or in jail, still smiling, still ready for a fight.

This guy was laughing as he swung off the bar stool. He was still laughing as he walked over to me.

The Face of Evil (1954)

I

McPartland is that rarity, a writer of tough novels who feels tough himself. (Was Spillane a barroom brawler? If so, did he win?)

McPartland was one of the Gold Medal blue-collar writers; had served in Korea; obviously knew the black-market milieu of that war; came back and wrote raw, rugged, at times very powerful novels; obviously drank, lived with a mistress and illegitimate kids before it was OK to do so; and died young of a heart attack. He was the kind of person who knew what it meant to be in trouble with the law, doing dumb impetuous things, getting into fights.

What comes across again and again in his novels is his understanding of power, the hard masculine will to dominate others, break them, destroy them. His bad guys are some of the most frightening in thriller fiction: Southern rednecks, syndicate “troopers,” the Mob. His fights are fights in which the loser can get hurt very badly.

When a black-marketing non-com says he’s going to scramble someone’s eggs with his combat boots (crush his testicles), or the middle-echelon syndicate enforcer Whitey Darcy tells the fixer Bill Oxford, “We’re going to make you cry, feller,” or when Buddy Brown, the twenty-year-old petty crook in Big Red’s Daughter (1955) tells Jim Work that he’s going to make him crawl, we know that’s just what they intend to do.

They are hard men.

King McCarthy in The Face of Evil (1955) is a natural fighter. Buddy Brown wins his first two fights with the hero—knocks him down with a sucker punch; gets a painful lock on his knuckles and punches him in the throat while they’re sitting drinking beer in a barroom booth. And the Syndicate, the Mafia, punish offenders ruthlessly. Oxford knows what it will be like to go to prison and have your kidneys smashed by an inmate, crippled with pain for the rest of your life every time you pee. Johnny Cool’s end in The Kingdom of Johnny Cool is dreadful.

However, in most of the novels there isn’t just violence, there’s also love, and things work out all right in the end for the hero and heroine. They very easily couldn’t, though. A strong, focussed counter-energy on the part of the heroes is necessary.

II

McPartland’s best book is The Face of Evil, about the fixer Bill Oxford, who’s been on the long downward slide of compromise, complicity, corruption, and has been sent to Long Beach by the PR agency to which he’s attached to ruin a genuinely decent reform candidate, upon pain of being stripped of all his high-living perks and slammed into prison. It is tense and well-made throughout.

The Kingdom of Johnny Cool is his other best novel. When it appeared, I wrote to Ross Macdonald (a total stranger, but he’d done a Ph.D. in English himself) to ask him to review it for a student journal I was co-editing. He declined, saying that it seemed to be simply Spillane-type melodrama. He was wrong.

The novel is a powerful account of a Sicilian criminal’s rise and fall in America—a more interesting one than W.R. Burnett’s Little Caesar (1929)—and it takes us into dark cold waters full of predators. McPartland was on to the Mafia as a subject twelve years before The Godfather, and his attitude towards it is far healthier than Puzo’s sentimental power worship. There’s nothing cute or admirable about McPartland’s Italianos.

Ed here: From Time Magazine‘s Milestones : “Died. John McPartland, 47, husky, bushy-haired chronicler of suburban sex foibles (No Down Payment), successful freelance journalist; of a heart attack; in Monterey, Calif. McPartland, who once wrote, “Sex is the great game itself,” lived as harum-scarum a life as any of his characters, had a legal wife and son at Mill Valley, California, a mistress at Monterey who bore him five children and who, as “Mrs. Eleanor McPartland,” was named the city’s 1956 “Mother of the Year.” Later, McPartland’s legal widow submitted the daughter of an unnamed third woman as one of the novelist’s rightful heirs. (9/14/58)”

June 23, 2012

Brave Hearts by Carolyn Hart

[image error]

Oconee Sprit Press continues to publish the early Carolyn Hart novels and does a fine job of it. Brave Hearts, the newest one, is for me the strongest so far.

Maybe because American Diplomat Spencer Cavanaugh plays so well into my suspicions about diplomats in general, his first appearance has almost as much dramatic effect as the ward going on in 1941. A truly unappealing guy because of the way he deals with his wife Catherine--master and slave--and the way he uses the war (or hopes to) to advance his career. She doesn't want to follow him to Manilla but has no choice. The plantation boss has spoken.

But it is there she meets story-tramp Jack Maguire, a reporter of some standing who comes equipped not only with pencil and paper but also wit and compassion. She is smitten from their few first minutes together at a ball.

The hallmark of this novel is Hart's handling of the history involved. Here she deals with the Japanese assault on the Philippines. For all the romance of the story, there is brute realism in the war scenes. I'd put the chapters aboard a ship--With Catherine and some German women aboard and the possibility of an enemy submarine--up against anything in macho war novels. Really great craft and fascinating interplay with the Germans.

Another big winner from Carolyn Hart and Oconee Spirit Press.

June 21, 2012

Forgotten Books:Home Town by Simenon

deRitter has lived on the edges of the underworld for many years. He is basically a small-time con artist who needs particularly gullible victims to be successful. For a reason even he can't understand, he returns to his home town with Leah, a prostitute, in tow. He has a fake emerald he hopes to make serious money with.

The story moves up and down the timeline. The reader sees deRitter as a boy growing up in a small, dull town--very much like the one that Madame Bovary despised--filled with and trouble. Off to war he went in his later teen years and after that he discovered how to beat the monotony of regular employment by working minor cons short and long.

In town again he sees old friends and old relatives; his strange relationship with his mother being the most disturbing. He also runs his con with the emerald and here the reader comes to see that he is not good at his work at all. And even when he scores he's unhappy. Which is where Leah the prostitute comes in.

She is plump--as he never forgets or forgives--she is ignorant in many ways and she is eager to get out of the town and back to what she consider civilization. But she also understands deRitter in ways he never understands himself.

He does not seem to know, for example, that he is afraid to let go of her. They have sex occasionally but their real bond is a version of the familial. More than girl friend she is mother/sister/consoler. And forgiver. She even manages to be amused about the occasional shame he feels for traveling with a prostitute. And she knows that the con he's running will lead to the tragedy that ends the short novel.

deRitter is a familiar figure in hardboiled crime fiction. The nickel-dime grifter that the real players use and toss away. Simenon turns the stereotype into a real human being. And his story into a bleak snapshot of self-unawareness and despair.

Ed Gorman's Blog

- Ed Gorman's profile

- 118 followers