James L. Cambias's Blog, page 35

April 25, 2018

April 19, 2018

Comic Timing

My talented wife was leaving early this morning on a trip, and I was getting ready to drive her to meet her ride. She glanced outside and said, "Ugh. It's raining." But then she brightened up and added, "At least it isn't snowing."

Five minutes later, as we were about to leave, I opened the door and saw snow falling.

When the weather has the comic timing of Jack Benny, it's hard to complain about having to drive in a snow shower.

April 15, 2018

Aristocracy in Space!

Why are there so many aristocrats in science fiction?

They're all over the place. In books you've got David Weber's Honor Harrington (who works for a Royal space navy and eventually becomes a Countess), Lois McMaster Bujold's Miles Vorkosigan (a Count who works for an Emperor), Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle's Rod Blaine (the son of a Marquis, who works for an Emperor), Frank Herbert's Paul Atreides (son of a Duke, and later Emperor himself).

They're all over the place. In books you've got David Weber's Honor Harrington (who works for a Royal space navy and eventually becomes a Countess), Lois McMaster Bujold's Miles Vorkosigan (a Count who works for an Emperor), Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle's Rod Blaine (the son of a Marquis, who works for an Emperor), Frank Herbert's Paul Atreides (son of a Duke, and later Emperor himself).

In films you've got Princess Leia from Star Wars, and Princess Aura from Flash Gordon. And on television Star Trek was positively infested with aristocrats. The Federation and the Romulans were practically the only civilizations in the Galaxy which weren't run by some kind of autocrat.

I'm puzzled by this because science fiction began as the most anti-aristocratic literature there has ever been. Between Wells's working-class/lower-middle-class emphasis on self-improvement and a rational new world of Science, and Verne's bourgeois love of "self-made" men rising in the world by pure merit, science fiction's DNA is staunchly egalitarian. Transplanted to America, it thrived among readers not unlike Wells and Verne themselves ��� working-class and petit-bourgeois strivers reading about the marvels of Radio! Airplanes! The Atom! Thinking Machines! Spaceships! And it worked, too: many of those striving young men actually did become successful in the new technologies.

So where do the aristocrats come from?

Well, one answer is that it's simply easier to have a society in which authority is individual rather than collective. Miles Vorkosigan works for the Emperor, and the chain of command is very short and clear. (Although Mrs. Bujold did show us some nice parliamentary maneuvering in A Civil Campaign.) There's no bureaucracy in the way.

It's more satisfying when evil authority is individual, too. When Paul Atreides takes revenge on his father's murderers in Dune, he can hardly track down and wipe out every soldier involved. Putting him in a society with an Emperor and a wicked Baron means there's a single neck to sever, so to speak.

Another reason for the aristocrats lies in those two first examples of noblewomen in science fiction films. Since time immemorial, what have heroes of romance done? They save Princesses. So a Planetary Romance has to include at least one monarchy with a Princess in need of saving from something. It didn't take long for that trope to be subverted, reversed, parodied, deconstructed, and who knows what else, but the seed had taken root.

In more recent years, the hereditary aristocrat has taken on a new form, especially in film: the autocratic corporate executive, who can scheme and plot if he's the bad guy, or reward the hero if he's the reasonable authority figure. He can even have a spoiled but good-hearted daughter if there's saving to be done.

I doubt we'll ever completely outgrow aristocrats in fiction, whatever form they take. Humans are social creatures, and we form hierarchies. One of the most ancient and satisfying stories (Heinlein called it "The Little Tailor" plot) is of someone rising in status and gaining a high-status partner. Whether you call it A Princess of Mars or Pride and Prejudice, that story will be with us as long as we are human.

For stories about bourgeois and working-class strivers, check out my ebooks Outlaws and Aliens and Monster Island Tales!

April 12, 2018

Search For The Old Ones

One of the great revolutions in human thought was the concept of "Deep Time" ��� the notion that the Earth and the Universe are vastly older than recorded human history, and even the origins of the human species lie long before the invention of writing. Charles Lyell, the Victorian geologist, was probably the first person to really understand the true age of the Earth, and his ideas in turn informed Charles Darwin's theories of the evolution of species.

But the first fiction writer to really grapple with the concept appears to be H.P. Lovecraft. In his novel At the Mountains of Madness he threw a crew of Antarctic explorers into a face-to-face confrontation with the original creators of life on Earth, a tentacled species called the Old Ones whose history spans not a paltry few thousand years, but close to a billion.

And once one starts looking into the history of life on Earth, the question does arise: why did it take so long for an intelligent species (us) to evolve? There's no strong reason why intelligence couldn't have appeared in some contemporary of the dinosaurs ��� or even a species of the Carboniferous era, as far from the dinosaurs in time as they are from us. They had brains; why didn't some species get a bigger one? (My explanation is that intelligence is simply not as inevitable or even as advantageous as we like to think. That's also my solution for the Fermi Paradox.)

The famous British TV series Doctor Who imagined intelligent reptiles from Earth's deep past, dubbed the "Silurians" because TV writers are terrible about looking things up. (There were no reptiles in the Silurian age.) They weren't bad chaps really, they just woke up from hibernation and were horrified to find their planet overrun by primates.

All good fun. Except . . .

Why are we so sure that we are the first technological civilization on Earth? In a paper for the Journal of Astrobiology, scientists Gavin Schmidt and Adam Frank tackle the question of how we might identify signs of past civilizations. We think of our cities and roads as durable things, but geology laughs at that. Over sufficiently long timescales, all artifacts get ground into dust. Schmidt and Frank identify some markers for past civilizations . . . and consider some otherwise mysterious events in Earth's prehistory which fit those markers. Hmm . . .

You can download the paper here.

April 8, 2018

There's No Pleasing Some People

I do most of the grocery shopping for my family. Yesterday I went on my usual big monthly run to the discount club, to stock up on stuff that comes in large packages. One of the items my talented wife asked me to pick up was cereal.

Was my return with cereal greeted with cries of rapture and gratitude? Were there squeals of delight? No. I got a lot of guff, that's what I got. You give someone magic-cupcake-flavored rainbow unicorn cereal, and you get guff. Rank ingratitude, I call it. Next time they'll get Grape-Nuts and like 'em.

April 7, 2018

Huh?

Can anyone explain why my Thursday post apologizing for missing a week of posting got more than 600 hits? That's about ten times more than anything since my gripe about Marty McFly's dad.

April 6, 2018

Still Bunk After All These Years

So here's an article from Quillette about "social constructionism" ��� in particular how postmodernists have applied the concept to the sciences, and how bad an idea it is. I was amused to see that one of the examples cited in the piece is Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar's book Laboratory Life, because that book was one of the course readings in my introductory History of Science course at the University of Chicago. I even wrote a paper about it (on a typewriter, so no copy survives).

What I remember about the book was its thundering disingenuousness. The authors reduced the work of a biochemistry laboratory to nothing more than making measurements and writing papers, which got them funding to do more measuring and writing. I was struck by the fact that the concept of information simply never came up in Latour and Woolgar's analysis.

It's particularly odd since of course that is exactly how the two authors would describe their own work. They weren't hanging around someone's lab taking notes, then writing a book for which they were paid. If you asked Latour and Woolgar what they were doing, they'd answer that they were gaining, and communicating, an understanding of how science works ��� in short, they were producing information. Just like the subjects of their study!

Way back in 1985 I concluded that social constructionism was bunk, and nothing I've seen in the past thirty years has changed my mind about it. Glad to see contemporary commentators are catching up with 19-year-old me.

If you're looking for entertaining stories guaranteed to be 100% bunk-free, check out my ebooks Outlaws and Aliens and Monster Island Tales!

April 5, 2018

We Apologize For The Interruption

Apologies for my absence. I was traveling and didn't have the time (or reliable Internet access) for 'blog posts. But because I was traveling on my own, I wound up having a lot of time to think about various things, and one of them was this 'blog. Up to now I have focused on "long form" pieces here, and used Facebook for any "here's a cool link" posts. I have decided to change that. From now on, everything goes up on the 'blog. I'll still link it to Facebook, but I want to keep more material in a medium I can control better.

So: expect more short "here's something" posts, some of which may have a little more political content than this 'blog has featured in the past. No full-bore polemics, though. I don't want to be a Moron With A Bullhorn.

I will still be doing longer pieces as I think of them, and the Random Encounter Tables will return. I'll be going back to my shelves for more Lost Games, and I'll be doing more book reviews.

Just to kick things off in this new, improved manner, here's a neat video! If these guys aren't crazy (and they did build the greatest airplane ever) the energy world is about to be flipped over like a card table in a tornado.

For some stories which aren't going to revolutionize the energy world, check out my ebooks Outlaws and Aliens and Monster Island Tales!

March 13, 2018

Random Encounters: On the Fantastickal Moon

We know what you'll find on the Moon if you get there via a Saturn rocket and Apollo Program Lunar Module lander. But what if you sail to the Moon aboard an elven galleon or step there through an enchanted silver door?

ENCOUNTERS ON THE FANTASTICKAL MOON

(Roll 1d20 when roving about the Lunar surface, 1d10 when stationary.)

Roll Twice and Combine

Plot-Advancing Encounter: Someone or something connected with whatever mission brought you to the Moon in the first place.

Bat-Men: 2d6 slender, hairy humanoids who fly by means of a membrane stretching from feet to wrists. They are armed only with claws and small stones they drop with great accuracy. Bat-men are curious, mischievous, and greedy, but their fragile bones make them flee any armed foes.

Fog: Dense fog lasting 1d4 hours (during the day) or until dawn (at night). You can't see more than a dozen feet in any direction.

Giant Hounds: A pack of 2d6 white hounds as tall as a man. During the day they scavenge and are quite friendly; at night they hunt and pursue anything they encounter.

Giant Moth: A moth with a 20-foot wingspan, looking for a suitable incubator for her eggs. If she scores a hit with her ovipositor, next Lunar dawn a brood of giant caterpillars hatch within her victim.

Lunar Elves: 1d6 Small and silver-haired elves armed with bows and sabers; during the day they are noble and benevolent, but when darkness falls they become cunning and evil.

Lycanthrope: During the day he takes the form of a giant black wolf. At night he reverts to human form.

Mooncalfs: 1d6 ugly, translucent-skinned quadrupeds about the size of a horse. They are harmless, but if threatened they give off a hypnotic cry which puts other creatures to sleep.

Rival Explorers: 1d8 visitors from Earth whose goals conflict with yours. They'll do anything to keep you from getting back before they do.

Cheese Mine: an open-pit mine worked by 1d8 dwarves with sharpened spades. The dwarves are protective of their claim, but have plenty of cheese to spare and will eagerly trade for wine and crackers.

Dust Pool: You stumble into a deep pool of fine grayish dust, too light to swim in and too dense to breathe. What's worse is that there's a giant Dust Worm at the bottom of the pool, coming to eat you up.

Enormous Mushrooms: They only open during the Lunar day, and send out clouds of hallucinogenic spores.

Giant Caterpillar: The last stage of life before it transforms into a moth, this caterpillar is the size of a bus. It rears out of the hole where it has been eating cheese and growing for years, hungry for protein.

Pathway into the Dreamlands: If you think this place is weird, you haven't seen anything.

Ruin: Huge shattered crystal domes and towers, built by the ancestors of the underground Lunarians, inscribed with their ancient runes.

Seashore: The black waters of a Lunar sea stretch before you. You can continue travel along the shore, or improvise a boat and take to the strangely calm sea.

Temple of Hecate: A vast pillared hall where 1d100 witches come to worship their dread goddess. Non-worshippers are sacrificed if they can't get away in time.

Tunnel Entrance: An opening into the caves of the insectile and telepathic Lunarians, who are perpetually on the verge of starvation and envy Earth's abundance.

Tracks/Aftermath: Reroll to see what you just missed.

SITUATIONS ON THE FANTASTICKAL MOON

A desires B

A wants to capture B

A wants B dead

A wants to go somewhere

A wants to solve a mystery

A wants X

If you're interested in stories which don't take place on the Moon, check out my ebooks Outlaws and Aliens and Monster Island Tales!

March 10, 2018

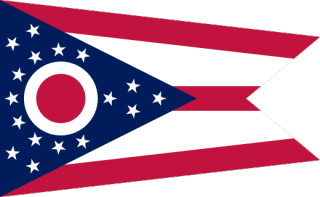

A Vexillic Issue

Most State flags are awful. There, I've said it and I'm not sorry. Even my home State of Louisiana has an awful flag. There are fifty States in the United States, and two-thirds of them have awful flags.

What makes an awful State flag? Well, twenty-nine States have flags that are horribly boring. You can blame the otherwise amazing 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Some bright person decided that the flags of the States should be on display ��� and promptly discovered that most of the States didn't actually have flags to display. Weirdly, in a nation which is legally and officially a union of sovereign States, most of those States never bothered to adopt a flag until some busybody from Chicago came nosing around.

The solution adopted by most States at the time was to just adopt the flag of the State militia. Those all have a depressing sameness: the State seal on a field of blue (for infantry) or white (for cavalry). A couple of States went wild and chose different background colors (New Jersey, Washington, Delaware), but that didn't really help. Nevada tried to get clever by putting the seal up at the canton (the upper-right corner) but didn't fool anyone.

The big problem with the seal-on-blue/white design is that State seals are terrible graphic elements. They're all horribly busy and fiddly, impossible to make out from a distance. So most State flags reduce to "a multicolored blob on a blue or white field." Five States tried to get around that problem by literally writing the name of the State on the flag. That's not a flag, that's a sign. You paint that on sheet steel and put it up at the border so people know what jurisdiction they're in.

The big problem with the seal-on-blue/white design is that State seals are terrible graphic elements. They're all horribly busy and fiddly, impossible to make out from a distance. So most State flags reduce to "a multicolored blob on a blue or white field." Five States tried to get around that problem by literally writing the name of the State on the flag. That's not a flag, that's a sign. You paint that on sheet steel and put it up at the border so people know what jurisdiction they're in.

Ranking slightly above the militia flags are a cohort of uninspiring designs, all of them obviously created by committees. This batch includes Iowa, North Carolina, and Missouri with their tricolors marred by fiddly bits; California with another road sign pretending to be a flag; and West Virginia and Wyoming, which just slapped a contrasting border on the basic seal-and-field model. Colorado's is good, though I take away points for putting the State's initial on it. A tricolor of blue, white, and gold would have been better.

Two States have what one might call "near-miss" flags. They are close to being good designs, but the creators couldn't keep from adding just one more thing, thereby shoving them off into mediocrity. Arkansas has a decent, distinctive flag marred by printing the name across the middle. Florida takes a nice strong design (Alabama's, in fact) and sticks another damned seal on it.

Two States have what one might call "near-miss" flags. They are close to being good designs, but the creators couldn't keep from adding just one more thing, thereby shoving them off into mediocrity. Arkansas has a decent, distinctive flag marred by printing the name across the middle. Florida takes a nice strong design (Alabama's, in fact) and sticks another damned seal on it.

Georgia's flag is one of the great "up yours" gestures of recent political history. After some residents, and a great many more non-residents, objected to the use of Confederate battle flag elements in the Georgia State flag, the legislature ditched the old design . . . and adopted a flag which is almost exactly the old national flag of the C.S.A. instead. Southern history buffs were satisfied, as were people who object to Confederate flags but wouldn't know the actual Stars and Bars if it bit them on the nose. All that said, sticking the State seal in the middle of the circle of stars on the Georgia flag makes it too busy, so points off for that. Mississippi also has a strong, if controversial design, but the Confederate battle flag in the canton now looks a little on-the-nose compared to Georgia's subtle trolling.

So which State flags do I like best? Here's my Top Ten:

Number Ten! ARIZONA has a good design, a little busy but certainly distinctive and colorful; it would look good painted on the side of a van.

Number Nine! TENNESSEE is a nice simple design, marred only slightly by the odd vertical blue stripe at the fly.

Number Eight! SOUTH CAROLINA breaks away from the seal-on-field pattern with a simple palmetto tree and moon. It obviously means something to somebody, and it's a complete departure from just rearranging elements of the U.S. flag.

Number Seven! OHIO can boast the only non-rectangular flag, a very jaunty-looking pennant. Even sneaking in the State's initial in the form of a circle doesn't spoil it (and makes a neat visual allusion to the Great Seal's all-seeing Eye).

Number Six! HAWAII's flag is a bit busy, but it has the honor of being an actual former national flag with some real history behind it, so that trumps mere graphics.

Number Five! MARYLAND has the greatest psychedelic eye-thrasher of a State flag ever created, with bonus historical points for being the actual coat of arms of the Calvert family, who founded the colony. If you're going to be busy, no half measures!

Number Four! TEXAS has a great flag, with tons of genuine historical importance riding on it. The design is strong and simple ��� it's such a good design that Chile used almost exactly the same thing. I think one reason Texans are always quick to consider secession is that they know they've got a killer flag to use as an independent nation.

Number Three! ALABAMA's flag could also be a nation's banner with no alteration. It's such a straightforward design I'm actually surprised no other polity grabbed it long before Alabama was even settled.

Number Two! NEW MEXICO shows how it's done: simple, completely distinctive, and very relevant to the people and history of the State.

But the best State flag of all belongs to . . .

But the best State flag of all belongs to . . .

ALASKA! It's wonderfully simple, but it throws a nice visual reference to the other boring seal-on-field flags with its blue background, and references the national flag (stars on blue), all with distinctive local relevance. There's even a visual multilingual pun: the stars are the constellation Ursa Major: the Bear. Which in Greek is Arktos, from which the word Arctic is derived. And Alaska, of course, lies on the Arctic Circle. Plus it has bears. The fact that this awesome flag was created by a thirteen-year-old orphan just makes it even cooler.

If you're interested in stories which don't actually involve flags, check out my ebooks Outlaws and Aliens and Monster Island Tales!