James L. Cambias's Blog, page 17

November 16, 2020

PhilCon 2020 Goes Virtual

This year's PhilCon ��� the venerable Philadelphia-era science fiction con now in its 84th year ��� is going to be all-online. On the plus side that means no New Jersey traffic and mall food; on the minus side it means no spontaneous conversations in the hotel lobby, no room parties, and no basic human contact. But a virtual convention is better than none at all.

Still, as in past years I will be participating, from my office in Massachusetts. Here's my schedule:

Friday November 20, 5:30 p.m.: Online Gaming: Not Just for Pandemics

Michael Ryan (moderator), Robert Hranek, James L. Cambias, Debby Lieven

The four of us will be discussing how the ongoing epidemic has affected how people play games -- will we go back to tabletops and rec rooms again, or is online gaming the future?

8:30 p.m.: From the Iron Bank to CHOAM: Business in Fiction

James L. Cambias (moderating), Anthony Dobranski, Elektra Hammond, Tom Doyle, Ian Randal Strock

A panel about the role of business and economics in fantastic fiction. How does a world's economy affect the stories one can tell? What does fiction get right and wrong?

Saturday November 20, 5:30 p.m.: The Oceans of Space

James L. Cambias, Tom Purdom, Kelli Fitzpatrick

I think I'm moderating this one. The three of us will discuss famous maritime science fiction, and how new discoveries in and beyond the Solar System may influence future ocean stories.

Sunday November 21, 1:00 p.m.: The Search for the Philosophers' Stone

Robert Hranek (moderator), Anastasia Klimchynskaya, James Prego, James L. Cambias, Elizabeth Crowens

We'll look at the history of alchemy, how discoveries in chemistry and physics changed our understanding of how matter works, and look at some other concepts which have shifted over time.

4:00 p.m.: Reading

I'll give con goers a glimpse into my forthcoming novel The Godel Operation, and the amazing far-future setting The Billion Worlds.

November 13, 2020

Ancient Alien Astronauts

When does speculative science cross the invisible line and become pseudoscience? That's a topic I grapple with when writing science fiction, and one which crops up whenever scientists air some of their wilder theories.

When does speculative science cross the invisible line and become pseudoscience? That's a topic I grapple with when writing science fiction, and one which crops up whenever scientists air some of their wilder theories.

For example, Dr. James Benford recently published a paper on searching for alien "technosignatures" on Near-Earth Objects in our own Solar System. In short, he wants to look for ancient alien space probes. Benford is a scientist, and his paper got published in The Astronomical Journal. It's speculative, but it's Real Science.

Fifty years ago, Erich Von Daniken published Chariots of the Gods?, a book asserting that artworks and artifacts of ancient human cultures contain evidence of contact with alien visitors. Von Daniken's book was pure pseudoscience, and it spawned a whole branch of pseudoscience with thrives to this day. His stuff has been debunked over and over but the idea continues to fascinate the public.

The maddening thing about the "Ancient Astronauts" pseudoscience is that it's not even crazy. The idea that the Solar System may have been visited in the distant past is entirely plausible. (Hence Benford's paper.) It's an interesting hypothesis which points to some very promising areas of research: detailed surface surveys of Near-Earth Objects, especially the Moon; radar mapping of other objects; the search for life on other planets; possibly even a search for chemical anomalies in ancient rock strata here on Earth.

If Erich Von Daniken had proposed those ideas the SETI community would honor him as a visionary. But he didn't. His "theory" is based on ignorance and flat-out lies about ancient civilizations on Earth, ignoring mountains of solid investigation and analysis by archaeologists and historians. The best analogy would be someone trying to prove that America was discovered and colonized by the Roman Empire, using the architecture of Federal buildings and Caesar's Palace casino in Las Vegas as proof.

And speaking as a science fiction writer, I have to say that Von Daniken's ideas of alien contact don't convince me. Like most pseudoscience involving contact with aliens, it simply isn't weird enough. His alien "chariots" are too similar to 1970s aerospace technology. His visiting space gods have two arms, two legs, and a head on top. If he'd cited artwork showing entirely non-human beings I might be persuaded.

So what? A dude writes a book of crackpot science and makes a fortune off it. What's the harm? Why do I care?

Two reasons. First, the whole "Ancient Astronauts" pseudoscience has tainted the well for actual scientific research into the subject. Until the arrival of tech billionaires who were science fiction nerds willing to spend millions of dollars to finance searching for aliens, there was virtually no support for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. It stank of woo. It has taken half a century for SETI research to overcome the "looking for little green men" stigma that people like Mr. Von Daniken helped pin on it.

And second, it's just wrong. Chariots of the Gods? is full of errors and misrepresentations ��� and not just about things which were disproved by subsequent decades of archaeology, but things which were known to be false when Von Daniken was writing. I'm pretty sure he knew it, too. Getting things right is important, or at least it should be.

One of the most dependable lines in the woo business is that "orthodox scientists" are too stodgy and unimaginative to accept the revolutionary ideas of the pseudoscientists. But that's actually the reverse of the truth. It's the pseudoscientists who are unimaginative, and their transparently bogus ideas get in the way of actual research into the speculative edges of science.

I've always been fascinated and amused by pseudoscience, but I think the practitioners could do a better job. Do your research! Come up with weirder ideas! Who knows, you might turn out to be right . . .

November 5, 2020

The Godel Operation Is Coming!

The Godel Operation, the first full-length tale of the Billion Worlds, is on the Baen release schedule for May 2021. I'm already working on a second Billion Worlds novel and a short story.

Best of all, we have cover art! Watch this space for new developments as the release date gets closer.

October 31, 2020

Twenty Years!

Today marks a significant anniversary. Twenty years ago, on October 31, 2000, the first crew launched to the International Space Station. Station crews are called "Expeditions," so Expedition 1 began on that date. We're currently on Expedition 64, with three in the pipeline and many more planned. The Expeditions overlap, so that the new crew arrives and can get acclimated before the old crew leaves. More recently, people have switched between Expeditions while aboard, to remain behind when the rest of their team goes home.

What all this means is that for twenty years now, there have been at least three humans living off Earth at all times. It's a small colony, and it's not self-sufficient, but one must crawl before learning to walk.

I called it a significant anniversary, but in time I hope "20 years in space" becomes an insignificant anniversary, as the human presence beyond Earth passes 50 years, a century, two centuries . . .

There will come a time when it is a matter of historical curiosity that there was ever a time when humans did not live off Earth. The date may someday be as obscure as the anniversary of the first time a human walked out of Beringia into North America, or when the first humans crossed the Suez isthmus to discover a whole planet beyond Africa. So let's honor the occasion in the fond hope that it will someday be forgotten.

October 30, 2020

Snow

It's snowing outside as I write. Feh.

The leaves aren't all off the trees yet. I was waiting for all of them to fall before raking. Now there's a layer of wet unraked leaves under the snow.

Feh.

October 28, 2020

The Need For Long Campaigns

Here's an interesting ��� and, I think, important ��� brief essay on the value of long things. Listening to long pieces of music, reading long books, and (for us nerds) playing long roleplaying campaigns. It's by David McGrogan, better known as "Noisms," the somewhat mysterious author of the amazing Yoon-Suin game setting.

Possibly revealing confession: in the course of writing this blog post I got distracted and managed to go down two different online "rabbit holes." This post is only 81 words long.

October 22, 2020

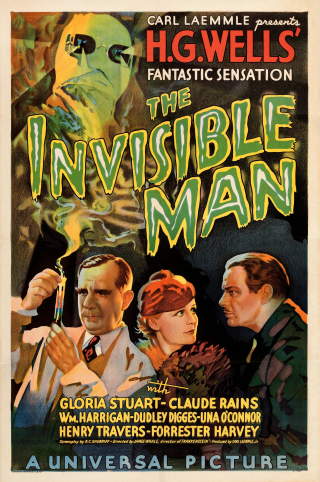

Notes on the Invisible Man

On Friday evenings my wife and I have a regular Movie Night. We've been doing it ever since it became impossible to go out to a real movie theater, and I expect we'll continue after (if) they re-open. To avoid conflicts over what to watch ��� or, worse yet, an "Abilene Paradox" situation where in an effort to find common ground we would end up seeing something that neither of us wanted to watch ��� we adopted a simple system. She picks the movie one week, I pick the next, we both watch whatever was picked, and no argument. It works pretty well and I recommend it.

Two weeks ago we watched the 1933 film The Invisible Man, directed by the peerless James Whale, based on H.G. Wells's 1897 novel. It was Claude Rains's breakout role ��� which is a testament to his physical acting and his amazing voice, because his face only appears for about five seconds at the very end.

Two weeks ago we watched the 1933 film The Invisible Man, directed by the peerless James Whale, based on H.G. Wells's 1897 novel. It was Claude Rains's breakout role ��� which is a testament to his physical acting and his amazing voice, because his face only appears for about five seconds at the very end.

As it was quite short, only 90 minutes or so, we spent a little time afterward looking at the special features on the disk, including the inevitable "making of" documentary. Like most specimens of the genre, this one included a couple of film critics trying to act like intellectuals, discussing the metaphorical significance of the Invisible Man in the film and Wells's novel.

And, as so many people do when discussing H.G. Wells, they kind of ran off the road into a ditch. One of them intoned quite solemnly that since H.G. Wells was a "progressive," the book is obviously about how oppressed "others" in society are "invisible."

Oppression as invisiblity was a great metaphor when Ralph Ellison used it for his 1952 novel about being black in America, Invisible Man (no "the"). But I don't think it has much relevance to Wells's book.

Why not? Several reasons.

First, Griffin, the Invisible Man of the title, isn't an "outsider" in the novel. He's short of cash for his research, but he's still a gentleman. An English gentleman in the 1890s was the ultimate insider, part of the class that literally ruled the world. He bosses around his social inferiors with unshakeable assurance and nobody thinks the worse of him for it.

Second, until he starts robbing houses and threatening to murder people, the people in the novel are very accomodating of Griffin. When he checks into a small country inn, all wrapped up to hide his invisibility, the proprietor isn't shocked or frightened ��� she's pleased at the unexpected windfall of a customer in the off-season. And when she glimpses his bandage-wrapped face she makes a point of mentioning that she has helped care for people with injuries before.

(By contrast, the film does make Griffin very much an outsider ��� a frightening intruder at the inn, the object of fear and suspicion from the start. Insert boilerplate reference to James Whale's sexuality here, although I suspect the real reason was that Whale was making a horror movie. That means something in the movie has to be scary, and the titular Invisible Man is the obvious choice. Also, Whale apparently loved to film having hysterics in front of the camera, and she got the chance to really let it rip in this one.)

Finally, the novel has three genuine outsiders in it, and H.G. Wells does not treat them with much sympathy. The first is a tramp, "Mr. Thomas Marvel," who is depicted as ignorant, cowardly, and dishonest. Griffin, the Invisible Man, bullies Marvel into being his henchman, but he betrays and robs Griffin at the earliest opportunity, ultimately getting away with money and the scientist's notebooks which he cannot understand.

The second is Griffin's landlord in London, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, who is also depicted as ignorant and cowardly, and gets his house set on fire. The third outsider is the "hunchback," the owner of a small and struggling costume shop in London. Unlike the other two, he is shown to be brave and resourceful, but Griffin beats and robs him anyway.

Griffin isn't the outsider, he's the one beating up outsiders ��� and the author invites the reader to sympathize with him when he does.

So, if it wasn't a parable against "othering" people, what axe was H.G. Wells grinding in The Invisible Man? Because this is H.G. Wells we're talking about, so there's definitely an axe and it's definitely going to get very thoroughly ground.

Well, it's important to remember that Wells's readers would instantly recognize the source of his idea of an Invisible Man. It's in The Republic, by Plato: the Ring of Gyges, which makes its wearer invisible. In Plato's dialog, his brother Glaucon uses it as part of a thought experiment about morality. The ring of invisibility meant that the wearer could commit any crime ��� in Gyges's case, seducing a queen and murdering a king to take the throne ��� with no fear of punishment. Nobody could identify the criminal, nobody could capture him. Glaucon posits that only the fear of punishment makes men behave justly, and with the Ring of Gyges any man would be unjust and feel no guilt.

As Plato has Glaucon say, "If you could imagine any one obtaining this power of becoming invisible, and never doing any wrong or touching what was another's, he would be thought by the lookers-on to be a most wretched idiot, although they would praise him to one another's faces, and keep up appearances with one another from a fear that they too might suffer injustice." (Note that Glaucon is asking Socrates to defend justice as a worthwhile good for its own sake; he's just "steelmanning" the side of injustice.)

Socrates's reply goes on for the rest of The Republic, and digresses into the organization of an ideal state, music, the role of fiction, and various other topics. You should read it, if you haven't. Any educated Englishman of the 1890s would know the story of the magic ring and be familiar with the rest of the book.

Now, H.G. Wells was a hard-core materialist. He didn't have any truck with God or divine justice. So, for a materialist, how to answer Glaucon's question? In a Godless universe, is justice merely a social construct, a kind of "mutual assured destruction" system in which humans agree to behave justly because they don't want to be the victims of injustice?

I think The Invisible Man is Wells's attempt to provide an answer. He does that by trying to refute the very premise of the Ring of Gyges: no man can truly escape the consequences of his actions. Not even an Invisible Man.

The novel constantly emphasizes the practical difficulties of Griffin's invisibility. He can't wear clothes, he can't carry things. If his feet get muddy someone will notice. In a crowded city like London he must be hyper-alert because nobody will avoid bumping him, and no driver will swerve to avoid running hi down. What should be a superpower is a curse.

The one deliberate murder Griffin personally commits in the novel is of a gentleman in the countryside who apparently catches sight of something the invisible man is carrying, and keeps following, trying to figure out what's going on. Griffin is already shown to be paranoid and psychopathic, but the thing which drives him to smash a man to death with an iron fence post is that his victim won't leave him alone. He's an invisible man who can't get any privacy!

And ultimately Griffin's "reign of terror" is ended by a road-mender hitting him with a shovel. No superweapon needed. The very idea of a man ��� even one with the power of invisibility ��� setting himself in opposition to society and conquering it is shown as absurd, the fantasy of a madman. Ordinary people are quite capable of stopping the invisible man, and I think that was Wells's entire point. People can get away with crimes only if the rest of us allow it.

October 8, 2020

Great Filters, Part 9: Odds and Ends

Well, I think I've come to the end of my series on the Great Filters and the Fermi Paradox. There are a few bits which didn't quite fit into any of the earlier posts. So here they are, in more or less random order.

Have We Looked?

First, there's the issue of what Michael Hart called "Fact A" ��� we don't observe any extraterrestrial civilizations. But the actual fact is that we haven't detected them, not that they don't exist.

The shocking truth is that we haven't actually looked very hard. For the first fifty years of SETI, searches for extraterrestrial signals were small, spare-time affairs, involving a few hours of instrument time now and then, aimed at a handful of stars. More recently, donations by whimsical tech billionaires and a thin trickle of government funds have finally made it possible to set up dedicated radiotelescopes scanning the skies.

But even the mighty Breakthrough Listen project has only managed to search about 700 stars for signs of radio transmissions comparable to modern radar systems. That's the biggest SETI survey ever attempted, representing a decade of work. It represents one quarter of one-billionth of the stars in the Milky Way. Another billion years or so and they'll be done!

We don't know if there are any other civilizations in the Milky Way. We can't even really be sure there aren't any alien probes parked at Earth's Lagrange points or on the surface of a near-Earth asteroid, calmly watching us.

The actual, known facts are really as follows:

1: We are reasonably certain there are no giant omnidirectional beacons using the entire energy output of a star to power transmissions. At least not on this side of the Galaxy.

2: We are sure there are no civilizations within a few hundred light years beaming messages directly at us with an antenna the size of the Arecibo radiotelescope.

3: We know Earth was not colonized by an alien civilization eons ago (Or was it? See below!), nor dismantled by Von Neumann machines.

Other than that, we don't know!

Someone's Got To Be First

Someone's got to be the first species to reach a level of technology capable of interstellar communication. Maybe it's us. I've even toyed with a mathematical argument in favor of that. If you're born randomly in the Galaxy, which species are you most likely to be born into? Obviously, the odds favor the species which lasts the longest and exists in the greatest numbers. So the fact that I am a human supports the idea that humanity is the Elder Race of the Milky Way.

Of course the same argument can be used to demonstrate that we're on the verge of going extinct, since the odds favor being born at the time of humanity's greatest population. I suspect the entire argument is bogus, but I haven't been able to prove it yet.

Anyway, if my earlier estimates about the number of civilizations in the Milky Way are in the right ballpark, then there's about a 1 in 50 chance we're the oldest technological species. Those are long odds . . . but they're not impossible ones. Unless and until we do detect another civilization, this seems like the best assumption.

A Wizard Did It

Or God, or the programmer of the simulated reality we're all living inside, or whatever. The assumption, again, is that the Galaxy (if not the whole Universe) was either created specifically for us, or the simulation was run over and over and we're the first ones to appear this time (see above). Amusingly, one of the arguments in favor of the simulation hypothesis is exactly the same as my mathematical proof that we're the first.

Once you add a supernatural component, two things happen. First, any analysis based on the observed Universe becomes pointless, because the only elements that matter are the choices of whatever intelligence is directing and arranging things. Study theology instead of astronomy.

Second, all the questions just get moved up a level. Where did that creator or simulator come from? What are the rules of the "real" universe in which the simulation is running? Again, study theology.

We're Them

Or, perhaps we've been ignoring a key possibility. Maybe life didn't originate on Earth or in the Solar System. Maybe we owe our existence to some seeding expedition a couple of billion years ago. Rather than disproving the existence of ancient starfarers, maybe life on Earth is evidence they stopped off here.

That doesn't really negate any of the other Great Filters I've discussed, but it would change the numbers around. We could expect to find life everywhere, which makes intelligence and technology even less likely.

Of course, as Arthur C. Clarke suggested in 2001, perhaps our intelligence is also the result of alien meddling. Again, if we are made rather than the result of evolution, see the section on supernatural creators above.

They're Everywhere

One topic which keeps cropping up in discussions of the Fermi Paradox is that even if the aliens aren't interested in transmitting messages in our direction, we should still be able to detect any large-scale activities of theirs. Dyson spheres, stellar mining, laser-launched interstellar missions, and so forth. But (so far) we don't. See above for not looking much.

Unless, maybe we have but don't know it yet. One of my personal theories is that some astronomical phenomenon we've attributed to natural processes is really the work of intelligence elsewhere in the Galaxy. If any astronomers can think of something which is uncommon but shows up in other galaxies and has only tentatively been explained, maybe that should be re-examined as a potential sign of extraterrestrial intelligence.

All right, I'm done now. What now? Now we wait and see.

October 1, 2020

Great Filters, Part 8: Space Filters

Wow, I've been doing this for two months and am not done yet. Now I know how Proust must have felt. Assuming Proust was writing blog posts about the Fermi Paradox, of course. So far I've looked at all the Great Filters which lie in our past ��� barriers to the evolution of life, barriers to intelligence and technology, and potential civilization-ending disasters. They certainly do reduce the number of possible advanced civilizations in the Milky Way, but only to a point.

Right now we're stuck at an estimate of about fifty civilizations out there among the stars, of which perhaps two-thirds have the wealth and ability to construct radiotelescopes or interstellar probes. Call it thirty. That's an awkward number because there's a very strong chance that many of them would be thousands if not millions of years older and more advanced than we are, which should make their activities easy to spot even across interstellar distances. But as yet we see nothing.

Today I'd like to consider three possible Great Filters which might explain why those civilizations ��� assuming they exist ��� are not doing anything we can detect. So these are Space Filters.

The first is the simplest, and most likely. Space travel, particularly interstellar travel, is just really hard. We may be able to send microchip-sized probes to nearby stars, but no colonists, no flag-planters. And given that it's likely to be tens of lightyears to the nearest world with even simple microbial life, maybe the effort is too great.

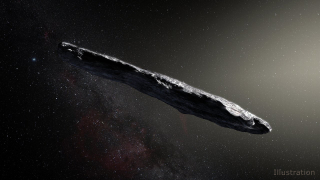

We do know that dangers wait in interstellar space: in the past few years we've detected two comets originating outside the Solar System. Now since presumably they didn't just start showing up right after humans invented ways to detect them, this suggests that interstellar wanderers are fairly common, and that space between the stars may be studded with rocks and shoals.

This would certainly put a damper on fast interstellar travel. Hitting a full-sized comet nucleus at any large fraction of the speed of light wouldn't just damage the starship, it would literally vaporize it. Even small rocks, pebbles, and dust grains ��� which, statistically, are undoubtedly far more common than visible objects like Oumuamua ��� would be catastrophic obstacles for star voyagers.

This would certainly put a damper on fast interstellar travel. Hitting a full-sized comet nucleus at any large fraction of the speed of light wouldn't just damage the starship, it would literally vaporize it. Even small rocks, pebbles, and dust grains ��� which, statistically, are undoubtedly far more common than visible objects like Oumuamua ��� would be catastrophic obstacles for star voyagers.

So go slowly, then. One thing which Oumuamua did demonstrate is that it's entirely possible to travel between the stars, as long as you don't mind spending tens or hundreds of thousands of years doing it. But is it really possible for any civilization to create a self-contained ship which can keep running that long? Or for any civilization to want to send out an expedition which won't report back for a thousand centuries?

Those are strong objections. Even the notion of firing off a bunch of Von Neumann self-replicating probes gets a little unattractive if your civilization might not last long enough to get the data they send back.

Now, it's possible that individuals in a sufficiently rich civilization might be able to launch their own interstellar missions. Right now a few tech billionaires on Earth are funding interstellar research essentially out of personal whims. The inhabitants of a Dyson Sphere with the full energy output of their home star to play with could do it as the equivalent of a high school science club project. But it's very hard to imagine any sustained, large-scale, systematic interstellar project under those circumstances.

I am going to call this one another Great Filter. Let's assume that half of those thirty advanced civilizations out there find the prospect of interstellar exploration too difficult, and so never do it. That cuts the number down to fifteen. Still awkward.

The second Space Filter is what some have called the "Dark Forest" problem. The idea goes like this: if you make yourself known across interstellar distances, some other civilization might decide to conquer or annihilate you. So everyone just keeps silent. The analogy is of a group of armed men stumbling around in a dark forest at night. None of them dares turn on a flashlight or call out, because anyone who draws attention could become a target.

I've written another long-winded series of blog posts about why I don't buy the Dark Forest idea at all. In addition to the reasons cited, there's another factor which I've only become aware of since writing those original pieces. Quite simply, our existence disproves it.

An advanced civilization can construct immense space-based telescopes, both radio and optical. Our own observatories are already looking for "biosignatures" and "technosignatures" on exoplanets within several hundred light-years. A civilization with kilometer-wide telescopes could do the same across a significant fraction of the Galaxy. This would be an especially important project for a paranoid xenophobic civilization planning to shoot first ��� the equivalent of night-vision goggles for that dark forest.

Our planet has had biosignatures in its atmosphere for billions of years. It has had detectable technosignatures for a few centuries, depending on how clever any potential observers are. The point is, we can already be seen across hundreds of light-years. Maybe thousands. Yet here we are. No interstellar killer probes yet.

Also, the detection and industrial infrastructure needed to monitor the whole Galaxy and zap any emerging civilizations should itself be detectable. So I'm calling the Dark Forest filter a dud. I just don't think it's likely.

And now the final filter, the one that I actually do worry about. In my discussion of civilization filters a couple of weeks ago I mentioned the danger that some civilizations might reach some kind of local optimum and simply stop advancing. No Scientific/Industrial/Economic/etc. Revolutions, just endless generations of Iron Age peasants, ruled by an endless series of alternating warlords and bureaucrats, until the Sun swells in the sky and the oceans dry up. Not a bad life, really, but one which leaves no mark on the Galaxy.

We got through that filter . . . or did we? It's possible there are several such dead ends in history, including one or more in our future. We may be on the cusp of one right now.

It's alarmingly easy to imagine a future for humanity in which we never leave Earth at all. Unmanned probes explore the Solar System a few square kilometers at a time, but that's all. No space colonies, no terraforming Mars, no Dyson Sphere Kardashev II civilization for us. Just endless "sustainable" generations of Information Age consumers, ruled by an endless series of alternating demagogues and bureaucrats, until the Sun swells in the sky and the oceans dry up (because nothing is really sustainable over time).

And across the Galaxy there may be dozens of civilizations caught in just the same trap, stuck on a single planet and unable to bootstrap themselves up to becoming interplanetary. Maybe . . . all of them?

That's a Great Filter I can see coming, and one we may be able to avoid. It means taking action ��� investing, donating, and letter-writing. If the Universe isn't worth fighting for, what is?

September 27, 2020

A Prediction

If you read this article ��� "The Bias that Divides Us," by Keith Stanovich ��� you will nod sagely about the cognitive bias it describes. And then you will spend ten or fifteen minutes reassuring yourself that you aren't affected by it.