Anthony Biglan's Blog, page 3

January 8, 2015

“Why should I praise, compliment kids or students for things they should be doing anyway?”

My experience is that when someone says that or asks that, they—themselves—are feeling terribly un-praised and under appreciated for what they do in life. The comment really means, “I am unappreciated, so why should I appreciate others?” I don’t attack people for this blinded comment about themselves, nor do I try to argue back from the mountains of evidence showing that all living humans need this. The comment arises from a wound, and the wound needs a healing. How can one do that? Here are two examples: I’ve modeled for PAX Partner Coaches (people who help implement the PAX Good Behavior…

The post “Why should I praise, compliment kids or students for things they should be doing anyway?” appeared first on The Nurture Effect.

The Value of Government

My dear brother-in-law has inspired me to elaborate on the efficacy of government. When I read Milton and Rose Friedman’s “Free to Choose” sometime in the eighties, I became convinced that free markets have an important function for society in that they evolve efficient and innovative products and services; better products and services get selected by buyers who are trying to maximize their own benefit and sellers who are motivated to maximize their economic gain. Over time new and more efficient products and services evolve. Societies which have adopted free market principles have seen considerable improvements in their economic wellbeing.…

The post The Value of Government appeared first on The Nurture Effect.

Benefits of the Mindful Pursuit of Values

Recent research in clinical psychology reveals three basic principles thathave relevance for all of us. The first is that rather than trying to control troublesome thoughts and feelings it works better to accept them and not struggle with them. In dealing with most problems of human behavior we are hampered by thoughts and feelings that get in the way of change. If you have ever tried to quit smoking, you may have found that cravings and difficulty concentrating drove you back to smoking. If you have been depressed, your efforts to get moving (a well-established antidote to depression) might have been undermined by…

The post Benefits of the Mindful Pursuit of Values appeared first on The Nurture Effect.

My Brother’s Keeper: The Vital Role of Prevention Science

We were pleased to hear about the “My Brother’s Keeper” Initiative. It addresses a very significant need in society. As President Obama indicated, young men of color are particularly at risk for a wide variety of problems. There are many factors that influence the statistics, primary of which is their high rate of poverty, harsher living conditions, institutional racism, stressful family dynamics and lack of opportunities. The consequences for the nation are substantial. Economist Ted Miller estimated the cost of the most common problems for all youth, such as violence, drug abuse, high-risk sexual behavior, poor academic achievement, high school dropouts and…

The post My Brother’s Keeper: The Vital Role of Prevention Science appeared first on The Nurture Effect.

How Can A Nurturing Environment Reduce Bias, Prejudice and Conflict Between Groups?

The classic experiment that shows this happened in the 1950s, the Robbers Cave study (Sherif, Harvey, Hood, Sherif, & White, 1988). An excellent 3-minute video summarizes how this classic experiment worked, which you can view at http://bit.ly/robbers-cave. Now that study happened more than 60 years ago with some middle-class boys in state park by the name of Robbers Cave in Oklahoma. The experiment happened in three stages: Stage one: The boys were randomly assigned to two groups, and never knew about the other group for a week. During the first week, each “team” (self named as the Rattlers or the Eagles),…

The post How Can A Nurturing Environment Reduce Bias, Prejudice and Conflict Between Groups? appeared first on The Nurture Effect.

January 5, 2015

Freaky Evonomic Calculations Drive America’s Border Problems

Drugs, violence, and lots of scangry (scared+angry) people pretty much summarizes the “bad” in America’s border problems. The “solutions” on the daily shout-casts on TV and the Internet are unlikely to work, because they don’t conform to what I’d call freaky evonomics, which is the bastard child of freakonomics and evolutionary science. Now, before you roll your eyes and scream that I’ve taken leave of all sensibility, read some of the data assembled—even if you think evolution is the invention of the devil. So why are all the really poor people in the U.S. and Central American making lots of babies…

The post Freaky Evonomic Calculations Drive America’s Border Problems appeared first on The Nurture Effect.

November 3, 2014

Can Children Be Taught To Have Empathy?

How do we cultivate the skills and values that people need to deal patiently and effectively with others’ distressing behavior? If you look at how young children learn to be empathetic you can see the key skills they need. The first skill is simply having an awareness of their own emotional reactions. Imagine that four-year-old preschooler Ryan opens the lunch his mom prepared for him and starts to cry. In a high quality preschool, one of the adults might join him and talk emphatically about how he is feeling: “Oh are you feeling really sad?” In doing so, she is helping him learn the names for his feelings.

When asked why he is upset, he says that his mother promised to put a cookie in his lunch, but there isn’t one. His teacher might commiserate with him, acknowledging that that would make her sad too and showing through her tone of voice and facial expression that she feels sad about his predicament. Their interaction helps Ryan not only to be able to describe what he is feeling, but also to understand that feelings result from things that happen to us. And as he calms down and gets the comfort of a caring adult, he is learning to accept and move through his emotions—a small step in the development of his emotional regulation.

But being empathic also requires that you be able to see things from the perspective of the other person. If I am going to experience caring and concern about how you are feeling, I first have to know what you are feeling. Research on perspective taking suggests that young children learn that others see things from a different perspective—literally. As they become more adept at realizing that what others see is not what they see, they become better able to discern the emotions that others are feeling.

The process is illustrated by a test that three-year-olds usually fail, but five-year-olds easily pass. Show a three-year-old a video of an adult putting a pencil in a green box while a child named Charlie watches. Then, after Charlie leaves the room, the adult takes the pencil out of the green box and puts it into the red box. When the child is asked what box Charlie will look in to find the pencil, younger children say the red box. Older children will correctly say the green box. The younger child has not yet learned to see things from Charlie’s perspective. Just because I saw you move the pencil, doesn’t mean that Charlie did.

If children are able to notice and describe their own emotions and also able to take the perspective of another child, they may then be able to experience the emotions that another child is feeling. Suppose that Ryan sees Kaitlin is upset and learns that her mother didn’t put the treat in her lunch that she had expected: Ryan may then understand and even experience some of the emotion that Kaitlin is feeling.

These experiences form the foundation for empathy—the ability to perceive and experience what another person is thinking or feeling. But by themselves, they do not guarantee the loving kindness that we need to build in our society. A child who perceived that another was upset about her lunch might use that as an occasion to tease the other child. To build the compassionate and caring society, we need to promote, teach, and richly reinforce such loving kindness.

You might think that kind behavior that is praised or otherwise rewarded by adults doesn’t count as a genuine instance of compassion. But that is how these vital repertoires are built. Each time you appreciate a child’s kind behavior you have taken another step on the road to building the behaviors and values of compassion and caring.

By cultivating these patient, nurturing family and school environments, we can help young children learn to understand and regulate their own emotions, understand the emotions of others, and react to others’ distress with empathy and caring. We help them go from their automatic distressed and angry reactions to more patient, empathic, and skilled ways of dealing with others distressed and distressing behavior. In the process, we will cultivate their valuing of nurturance of themselves and others.

In sum, you can cultivate empathy and the kindness that can go with it by:

1. Helping children to learn about their emotions, by empathetically joining them when they experience emotions and teaching them the names for their emotions and the circumstances that prompt them.

2. Teaching them to see that other people see the world from a different perspective. Simple discussions about what you see and what they see can help.

3. Teach them to recognize emotions in others. You can ask them about what they think other people are feeling, for example, in reading stories to them or when the see something bad happen to another.

4. Ask them about the emotions they feel when they see others feeling sad, or angry.

5. Notice and express your appreciation and approval when you see them acting in kind ways to others or when they show that they are taking other people’s perspectives.

October 20, 2014

Punishment Is Not the Answer to Domestic Violence

There is a certain irony to the way our public discussion about the domestic violence of NFL players. The emphasis is on punishment in reaction to what they have done. Criminal prosecution, banishment from the league, firing of the commissioner, shaming of the league. But I have not heard one word about prevention or rehabilitation.

Don’t get me wrong, I think there has been egregious conduct on the part of many NFL players and obtuse and insensitive actions by NFL officials. But while this media circus will enhance the bottom line of media organizations, I doubt that it will contribute to less violence in families.

What would be the ideal outcome in the current public discussion about domestic violence? Wouldn’t it be good if more people learned that we have good ways to help parents learn gentle and effective ways to teach their children and that they could prevent much child abuse if they were made widely available? Wouldn’t it be ideal if the NFL adopted policies that influenced their players to become better fathers and husbands? And what might we wish for someone like Adrian Peterson? Wouldn’t the best outcome for him and his family be that he learned about gentle and effective ways to be a father, repaired his relationship with his son, raised a healthy and successful boy, and became a spokesperson nurturing parenting? Could it be that his redemption is as important an outcome as any?

There are numerous effective family interventions that can help families replace harsh discipline, with gentler, more effective, more reinforcing—more loving—ways of raising children. These programs teach us a lot about human behavior that can be applied not just to family relations, but to how we deal with each other throughout society. There is a place for criminal penalties and banishment both to punish the behavior of individual offenders and to warn others about the consequences of harmful behavior. But in a society that imprisons a larger percentage of its citizens than any other country, and yet continues to have higher rates of murder, rape, and assault than Austria, Germany, and the UK, we should stop to consider whether our punitive way of life is a problem.

Do I think Peterson should serve time in prison? I don’t, so long as he truly leans into to learning better ways. He and Charles Barkley have pointed out, what evidence shows is the true, that these kind of harsh techniques are common among African American families. If you are particularly sensitive to the problem of child abuse, perhaps because you were abused and don’t want that to happen to anyone else, you may feel strongly that there should be no hint of forgiveness, lest it suggest to others that abuse will be tolerated. I too feel strongly that we should create a society where abuse of children, spouses—or anyone else–is rare and effectively dealt with. But how likely is that that criticizing the African American community for their discipline practices will achieve that outcome?

Isabel Wilkerson’s book The Warmth of Other Suns tells the story of the migration of African Americans from the South to the North and West over a fifty year period. She tells us that in Florida alone 266 black people were lynched between 1882 and 1930. In one case, a young black boy sent a Christmas card to a white girl. When she showed it to her father, a posse of white men captured the boy, forced his father to watch as they tortured him and drowned him in the river. When I read her book, I realized why African American discipline practices were so harsh. If your five year old son could be beaten or even killed if he acted “uppity” to a white person, wouldn’t you beat him in a desperate effort to keep him from doing anything that would get him killed?

It is surely in the nation’s interest and in the interest of the African American community to adopt less harsh parenting practices. But just as a therapist does not get very far with a parent that they criticize, but does move them when they join the parent around their hopes and aspirations for their child, perhaps we need to find less harsh ways of dealing with domestic violence.

I realize that if you have experienced abuse at the hands of a parent or spouse, you may be so angry that you want to be sure that such behavior is always punished. But psychologists are increasingly adopting a pragmatic approach to these problems. The most productive question is not whether abusers are wrong and should therefore be punished, but how we can reduce the likelihood that they will abuse again. And when the abuse becomes a matter of public discussion, we should ask how we can deal with it that make it less likely not only that someone like Adrian Peterson will not abuse again, but how we can use this as teachable moment to prevent abuse in many other families.

October 16, 2014

We Can Greatly Reduce Child Abuse

Thanks to the NFL we have the opportunity to have a useful public discussion about punishment and violence in America’s families. I want to offer a somewhat different way of thinking about this than I have seen in media so far. So far the primary focus has been on punishing wrong doers. Prosecuting Adrian Peterson, banning him and Ray Rice from playing, demanding that Roger Goodell resign, establishing stronger penalties for off-the-field misbehavior.

Given that the NFL policies regarding domestic violence have the potential to reduce domestic violence going forward—both through direct effects on players and through changes in our national norms—I found the leagues proposed policies encouraging. But in general, I was struck by the fact that we mostly react to tragedies with punishment and fail to do the things that could prevent such tragedies from happening.

My first thought when I heard about the Adrian Peterson case is that I knew just how he could navigate this situation and come out the other end a better person and one who made a significant contribution to society. If I were hired to counsel him on his predicament, I would have him go to a therapist who was skilled in one of the numerous evidence-based family interventions that have been developed in recent years. For example, my friend Marion Forgatch and her colleagues developed Parent Management Training, Oregon, which is in use in growing use in a five U.S. states seven other countries. The program has shown numerous benefits for children and parents as much as nine years after it was delivered.

The key feature of this and every other effective family intervention is that it helps parents replace coercive parenting practices such as hitting and yelling with positive methods of developing children’s self-control, cooperation, and skill. The positive methods involve playing with children, learning to follow their lead, and richly reinforcing their positive behavior through attention, praise, and, when needed, explicit rewards such as stickers, time with a parent, and special privileges. These programs also teach parents how to reduce undesirable behavior with brief timeouts and chores.

In working with an angry or abusive parent, therapists seldom lecture or criticize. Why? Because as a practical matter, most families are free to leave therapy and they will do so if they feel attacked and criticized. A good therapist who was asked to see Adrian Peterson would begin by listening to him about his situation and his concerns. You might think that this would end up supporting his cruel behavior toward his son. But that is unlikely. My experience is that when people don’t feel threatened that they have to defend bad things they have done, they readily acknowledge that they would like to find better ways to raise their children.

Each year in this country six million children are discovered to have been abused and more than 4 children a day are murdered. We have the knowledge to prevent a huge number of these tragedies. Marion Forgatch’s program is only one of many that have proven benefit in helping parents replace harsh and inconsistent discipline with gentle and effective means of supporting children’s development. Slowly, states and communities are beginning to make these programs available to parents who need them. One good thing that could come of out of the Peterson case, is public demand for tested and effective programs that can prevent abuse.

As a society we invest far more in reacting to outrageous conduct than we do in preventing it. We investigate child abuse and domestic violence and punish perpetrators, but, thus far, we have failed to make programs that could prevent these problems widely available. Perhaps if we begin to abandon our fixation with punishment, we can begin to provide programs for families that truly reduce the rates of domestic violence.

July 23, 2014

Freaky Evonomics: Dopamine Genes Running Across the Border

What makes people flee violence and endure danger of illegal border crossings to come to the United States?

What makes people risk carrying illegal drugs across the border?

And, what makes the millions of American citizens in the US crave illegal drugs in the US?

One could blame bad parents, too lax or too harsh parents. One could blame believing in the wrong religion or no religion. Those judgments cannot see impossibly tiny dopamine genes that do not respond to social, physical, and biological events in a “moral way”. Those genes change how dopamine is expressed in our brains, and how we are embodied in the flesh and behavior. Those genes have spread in humans for good reason.

Perhaps you’ve noticed that a good portion of people exposed to violence, deprivation or human caused oppression become quite impulsive and violent—even fearless. Another good portion of humans may hunker down and try to hide or disappear under the same conditions, perhaps seeking drugs to soothe themselves.

Dopamine depletion or pruned dopamine receptors in the brain make people do things that seem illogical, dangerous. Except, it’s not so foolish from the dopamine gene’s perspective. These responses seem to be a function of variations, often called alleles of dopamine genes.

Not to be too technical, I have to remind folks, that genes struggle to survive just as individuals do. This is a great revolution in understanding of evolution of selfish genes that happened in the 1970s. Here’s the scoop, selfish genes make foolish people do, to paraphrase a line from Chris Isaacs’s song hit, “Wicked Game.” I’m none to happy to know that there are genes in me that care not one whit if I survive or thrive, only if they do.

I’ve yet to hear anyone talk about the underlying Freaky Evonomics driving our problems at the border. Remember, Freaky Evonomics is Freakonomics + evolutionary history that selects genes to solve problems. So I am going to, damn the torpedoes and full speed ahead.

So, here we go. You are in a group of humans. Bad things happen that threaten you and your peoples. Your neighboring humans want to kill you, eat you or enslave you. Or, the environment dramatically changes, which means there won’t be enough food, water or other resources to sustain you and yours.

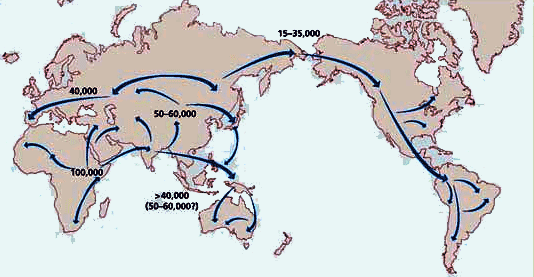

Your choice: Stay or move. Some of you have genes that scream “stay”, others have genes that say “leave.” Which genes spread across the planet: stayer or mover genes? Do the math!!! Lot’s of stayers die, and don’t reproduce in their dangerous settings in the same frequency. And a quite a few people who leave don’t make it, but enough make it to the promise land, where they have babies. Their babies have babies, and they move over the next hill and the next hill for each successive generation. You have just described the spread of dopamine receptor 7 and 2 repeats across the planet—along the routes humans took from Africa to Europe, Asia and the Americas. The further away from Africa humans are, the more likely they were to have either of these two dopamine versions. Check it out, http://bit.ly/dopamine-migration.

Stayer genes say, “don’t take risks.” Mover genes say, “move your butt and get the heck outta here.” Which humans went from the Siberia, Beringa and then to the tip of South America? Which genes boarded canoes for move all across the Pacific? Which genes left the original 13 colonies to cross the Cumberland Gap?

It wasn’t the stayer genes, and those moving genes are screaming to leave Central America where terrible threats are happening every moment. If you stay there in Honduras or other wretched, violent places, the chances are you will be killed or consumed or controlled parasitically. Please remember, dopamine gene variations 7 or 2 alleles have absolutely no understanding or care about national or “legal” boundaries. No, those alleles are all about survival, come what may. Again, recall the Jurassic Park movies, set in the same areas: “Life finds a way.”

Next installment of Freaky Evonomics: How and why the same dopamine 7 and 2 gene variations are the cause of the USA being the number one consumer of illegal drugs from across the border.