Elizabeth Winthrop's Blog, page 6

May 11, 2014

Mother’s Day

It’s Mother’s Day in the States, but not, it turns out, in England. They had theirs about a month ago. It’s called Mothering Sunday and always falls on the fourth Sunday in Lent.

My mother  was very dismissive of what she called, “another Hallmark holiday.” “Every day should be mother’s day,” she’d remark with a sniff, and I must say I agree with her. Whenever I noted the day with a call or a visit or a flower delivery, we’d have the exact same conversation and it became our own kind of Mother’s Day ritual.

was very dismissive of what she called, “another Hallmark holiday.” “Every day should be mother’s day,” she’d remark with a sniff, and I must say I agree with her. Whenever I noted the day with a call or a visit or a flower delivery, we’d have the exact same conversation and it became our own kind of Mother’s Day ritual.

So, on this Mother’s Day, I’ll just list the bits and pieces of my mother that I brought with me on this tour of the places she lived in England.

-a pale blue satin nightgown that Zuni, her faithful Paraguayan caregiver, urged me to take when we were clearing out her house. It’s become one of my favorites.

-the two gold link bracelets with the initials of each of her fifteen grandchildren and the four great-grandchildren that were alive when she died. I’ve worn them ever since her death 19 months ago.

-the last bottle of her favorite perfume

-and finally the pink cotton shoe bags, that travelled with her to Poles Convent School in April, 1939 and stayed with her the rest of her life. She always took them when she went on trips. I remember them most recently when I helped her pack for our trip to the island of Guernsey in 2004 to visit Bee, her oldest and dearest friend.

“Where did you get these, Mummy?” I asked as I slipped her black flats into the two worn, but still serviceable, shoe bags.

“The dressmaker in Gibraltar made them for me when I left for Poles. She made all my clothes. And of course, the initials are hand embroidered. ”

PBH for Patricia Barnard Hankey.

Of course.

May 10, 2014

My mother’s convent school, Part 2

Angela and Lynda, who work in the shop at the Marriott Hanbury, were very helpful. They gave me a long historical report on the house and directed me to the nuns’ cemetery where I found the headstone of the Reverend Mother, to whom my mother must have curtsied many a time. Philomena of all names, for those who have seen the recent movie starring the incomparable Judi Dench.

Angela and Lynda, who work in the shop at the Marriott Hanbury, were very helpful. They gave me a long historical report on the house and directed me to the nuns’ cemetery where I found the headstone of the Reverend Mother, to whom my mother must have curtsied many a time. Philomena of all names, for those who have seen the recent movie starring the incomparable Judi Dench.

I realize now what I’m feeling as I walk down these halls where my thirteen-year-old mother (can you find her?)

where my thirteen-year-old mother (can you find her?) dressed in her school uniform, ran to answer the call of the bells, the stern demands of the nuns and where, when she looked out the window at the cold Hertfordshire hills, must have longed for the ocean breezes and the orange trees of Gibraltar.

dressed in her school uniform, ran to answer the call of the bells, the stern demands of the nuns and where, when she looked out the window at the cold Hertfordshire hills, must have longed for the ocean breezes and the orange trees of Gibraltar.

I’m way ahead of her. I know what happened and where she went from here while she knew nothing that was to come, the way none of us do. Neville Chamberlain declared war on September 3, 1939, the week before she returned to Poles  for her second year. It was better than the first. She’d made fast friends with Bee Mowbray, she’d proven to be quite the scholar and she’d survived one term away from home. It was the time of the Phony War when everybody trudged about London with clumsy gas masks hitched over their shoulders, but Hitler was still thinking he might bring England around so the Blitz hadn’t begun.

for her second year. It was better than the first. She’d made fast friends with Bee Mowbray, she’d proven to be quite the scholar and she’d survived one term away from home. It was the time of the Phony War when everybody trudged about London with clumsy gas masks hitched over their shoulders, but Hitler was still thinking he might bring England around so the Blitz hadn’t begun.

However, by her final year, when she placed high enough in the rankings to be considered for the Oxford entrance exams, the war arrived at her doorstep. Girls in England had to do their bit too. So she and Bee were forced to enroll in the Carr Saunders Secretarial School in Gloucestershire to start in the fall of 1942. That summer, the two girls would stay with the Mowbrays at Allerton Park in Yorkshire. My grandmother was grateful to know Tish would be well away from drab and dangerous London that summer, never suspecting of course how much that visit would shift the trajectory of her sixteen-year-old daughter’s life. Those years away from home in the drafty halls of the Jacobean house toughened her up for all that was to come. Love yes, but so much loss too.

My mother couldn’t wait to get out of the place, but I feel an odd sadness at leaving Poles. For two days, I’ve walked along paths she walked before I ever knew her, I’ve looked through windows that she might have opened and seen much the same view that she saw, seventy odd years ago. I expect I won’t be back and yet, I don’t want to leave.

We stop at the end of the driveway for one last look. There’s that tree again. And the strange blue Xes on the walls that I’ve since learned are called, oddly enough, “blue brick diapers.” And the arched passageway that once led to the stables and now serves as the entrance to the hotel spa where my husband booked me a relaxing massage. That would have made my mother smile. She couldn’t stand anybody touching her, but loved it when I took care of myself. This entire trip is a way not just of finding her, but of taking care of myself. She would have approved.

This entire trip is a way not just of finding her, but of taking care of myself. She would have approved.

May 9, 2014

My mother’s convent school

My mother was not surprised when, in 1939, her parents decided to take her out of the simple day school in Gibraltar in order to send her to Poles, a Catholic boarding school in Hertfordshire, England, but she always remained mystified by the timing. Why in April? she wondered out loud to me years later. Why not when the school year began or at least the winter term?  In any case, the only good thing about it was that another girl named Patricia, nicknamed Bee, (my mother was always called Tish), arrived as a new girl on the exact same day. Their bond was instant and lifelong. Bee was my godmother and in 2004, I took my mother to the island of Guernsey so she could be there for Bee’s 80th birthday celebration.

In any case, the only good thing about it was that another girl named Patricia, nicknamed Bee, (my mother was always called Tish), arrived as a new girl on the exact same day. Their bond was instant and lifelong. Bee was my godmother and in 2004, I took my mother to the island of Guernsey so she could be there for Bee’s 80th birthday celebration.

And now, ten years later, I’ve decided to travel to all the places in England where my mother lived or went to school. So at three this afternoon, with my loyal and plucky husband at the wheel, we turned down Poles Lane and drove up to the front door of what used to be the Poles Convent, and is now the Hanbury Manor, a Marriott Hotel and Spa. My first reaction? Pure unbridled relief at having survived at least twenty roundabouts driving on the left hand side of the road.

I asked that we be put in the Manor House to insure we would be sleeping in the section of the hotel that housed the entire convent school. Might we be staying in a room my mother once occupied? It’s certainly possible, although the redecoration makes it hard to imagine. In those days, she didn’t have sumptuous tasseled curtains framing the windows of her dormitory room or wall-to-wall carpeting or a mini-bar or even a lift to carry the girls to their quarters. The shared bathrooms, down a long hallway, were always cold. In fact there was no heat at all in the school. You just added another layer of woollies if you had them.

Poles was run by a society of nuns called the Faithful Companions of Jesus. (My mother and Bee nicknamed them the Frightful Chums.) Our bedroom looks out on the sculpted greens of an eighteen-hole golf course. Remarkably enough, my mother looked out on the same scene as Henry King, the retired diamond merchant who bought the house from the Hanburys, the original owners, added the golf course. Sadly, Mr. King’s son was killed in World War I, and he himself died in 1920. The family seemed dogged by tragedy as the next year, their daughter, Muriel, died of severe burns when the smoker she was using to calm the bees in their hives, in malfunctioned and set her on fire. Soon after her death, her widowed mother put the house on the market. The Faithful Companions bought it two years later to set up Poles Convent.

My mother spent three years here. She dislocated her knee doing a spontaneous pirouhette on a stone floor while waiting for lunch one day. The nuns told her to take two aspirin and stop complaining which is probably the reason why her favorite phrase was always NO POINT FUSSING. She prayed daily in the chapel, now used as a dining hall.  She stood in front of this magnificent tree

She stood in front of this magnificent tree

for countless class pictures (she is second to the left from the small girl in front) and cast photographs from A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

and cast photographs from A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

and a production in which she played Anne Boleyn.

My grandmother yanked her out of Poles in April of 1940 in the hopes of getting her out of England during the war, but no sooner had she and her brother and her mother returned to Gibraltar, then they were evacuated right back to England. So on May 30,1940, she found herself back behind the sheltering walls of Poles where despite the nuns’ strict rule against radios or news of any kind, they could occasionally hear the bombs dropping thirty miles south in London. When the bombs got closer, the girls were all instructed to zip themselves into their combat suits, (which looked just like the one Winston Churchill often wore) so the nuns could herd them all down to the safety of the basement.

I’ve found two lovely ladies in the Marriott gift shop who are the only ones here who know anything about Poles Convent which closed in 1986. I hope to do some more exploring with their help.

May 2, 2014

Following in My Mother’s Footsteps: A Trip to England

As many of my readers know, I’ve been researching my mother’s childhood in Gibraltar and England for a number of years. While she was still alive I traveled to Gib, as she always called it, to see firsthand what it was like to grow up on the Rock on the edge of the Mediterranean where you lunched across the border in Spain and spent the afternoon watching polo in Tangiers. The Barbary apes loped down to town to snatch the laundry off the rooftops, oranges grew on trees and the breezes blew balmy and tasted of salt. I returned with lots of stories and a book of pictures that my mother pored over every day as her memory faded and her youthful existence felt more immediate than the visitor who’d just dropped in for tea.

As many of my readers know, I’ve been researching my mother’s childhood in Gibraltar and England for a number of years. While she was still alive I traveled to Gib, as she always called it, to see firsthand what it was like to grow up on the Rock on the edge of the Mediterranean where you lunched across the border in Spain and spent the afternoon watching polo in Tangiers. The Barbary apes loped down to town to snatch the laundry off the rooftops, oranges grew on trees and the breezes blew balmy and tasted of salt. I returned with lots of stories and a book of pictures that my mother pored over every day as her memory faded and her youthful existence felt more immediate than the visitor who’d just dropped in for tea.

I promised her that I would visit the places in England where she spent her childhood holidays and the years of the war, but as she grew increasingly frail and disoriented, I didn’t feel comfortable taking an extended trip out of the country. Now that she’s gone, I’m ready to keep that promise.

My fiction writing has always been enriched by an intimate knowledge of the place where I’ve chosen to set my books. Whether it’s my grandmother’s house in Connecticut or an island off the New England coast or the mill town in Vermont where Lewis Hine took some of his best known child labor photographs, an intimate acquaintance of setting enriches and expands my understanding of the characters in my fiction.

Now that I’ve come to the end of the first draft of my family history, A FRAGMENT OF WHAT YOU FELT, Searching for My Mother, I’m ready to see where she lived in the years between her exile from Gibraltar as a young teenager and her transatlantic crossing as an eighteen-year-old pregnant bride. If I walk through the rooms of her convent school, stand in her grandmother’s Cotswold garden and wander the hallways of the Yorkshire castle where she met my father, then surely, I’ll understand better the determined young British colonial who left her job as a decoding agent for MI5 so she could marry an American parachutist twelve years her senior who she barely knew.

When I began to plan this journey, I discovered to my amazement that all the important places in my mother’s life are open to the public. Her convent school is a hotel. Her grandmother’s house is a bed and breakfast. Her best friend’s home is a Gothic Revival castle, now open for tours.

Will I know her better if I walk in her footsteps? The only way to find out is to go.

May 8-10: We’ll be staying at the Hanbury Marriott in Hertfordshire. This building used to be Poles Convent, the school my mother attended from the age of 13 to 17. I’ve asked that we be put in the Manor House, the main hall, which means we might actually be sleeping in what was once my mother’s dormitory room.

Driving from Ware to Bourton, we will stop in Oxford on Saturday May 10th for lunch with Margaret and John Barnard Hankey, my mother’s second cousins who I have never met. We will also connect with them again at Fetcham Park later in the trip.

May 10-13th: We’ll be staying at Whiteshoots Bed and Breakfast in Bourton on the Water up in the Cotswolds. This was my great-grandmother’s last house. She was Ellen Gertrude Moon, the mother of Arthur Hankey, my paternal grandfather. My mother often visited her so we’ll most probably be sleeping in the one of the rooms where my mother stayed.

While in the Cotswolds, we’ll be visiting Stanway House in Broadway.

This is the home of the Earls of Wemyss. I’ve been in touch with the present Earl of Wemyss (pronounced Weems) who has kindly agreed to have us drop by for a private tour. Stanway is where my mother (and her good friend, Bee Mowbray) lived and went to secretarial school from August 1942-March 1943 when at the age of 17, my mother was taken on at MI5 as a decoding agent.

May 13-15: We’ll be staying with Edward and Nell Stourton, in the stable house at Allerton Park in Knaresborough, Yorkshire. In the summer of 1942, my parents met at Allerton Park as my father had enlisted in the Kings Royal Rifle Corps, training in nearby York, and my mother was visiting her best friend, Bee Mowbray. Bee’s father, Lord Mowbray and Stourton, was the Premier Baron of England and the owner of Allerton. On August 31, 1942, the night before the Royal Canadian Airforce requisitioned Allerton to use as a barracks, Lord and Lady Mowbray gave a farewell party and invited the “Yanks” from the regiment which was training nearby in York. My father (age 28) sat next to my mother (age 16), and the rest is history. The castle itself has been purchased by an American named Gerald Rolphe, but Edward Stourton and his wife, Nell, kept the stables and have kindly invited us to stay. We’ll join the public tour on May 14th, and the tour guide has promised to take us upstairs to see parts of the house not open to the public.

While in Yorkshire, I will also be visiting Ampleforth, which is the Catholic equivalent of Eton. This is where my uncle Ian, my mother’s only brother, went to school from the age of 9 to 18. He joined the Kings Royal Rifle Corps in May, 1940, soon after the family was evacuated from Gibraltar, and was killed in the western desert at the battle of Alma Halfa, on August 31, 1942, the same day my parents met in Yorkshire. He was 21 years old.

May 15-23: We’ll be in London for the last week meeting more cousins through the Gibraltar side who contacted me through the Internet. I’ve planned two day trips, the first to Winchester to visit my father and uncle’s regimental museum. The Kings Royal Rifle Corps were also known as the Green Jackets. The regimental historian, Christopher Wallace, who has been very helpful with my research over the last four years, will be giving us a tour.

The next day we’ll travel down to Fetcham Park in Surrey where my grandfather, Arthur Hankey, lived until he married my grandmother, Cecilia Mosley. The people at Fetcham are thrilled about our visit and are arranging a lunch for me to talk to the historian of the house as well as Hankey cousins. They will give us a tour of the house and the graveyard where many Hankeys are buried.

Stay posted. I’ll be writing more here about this very personal journey.

February 25, 2014

HARRIET THE SPY TURNS 50

I was thrilled when Random House asked me to contribute to the 50th anniversary edition of Harriet the Spy.

Harriet M. Welsch is a girl who says what she wants (in her spy book) and defies all the dictums of her time. She wears black, high topped sneakers and speaks the truth. I first encountered the book while applying for a job at Harper Junior Books, the division that under Ursula Nordstrom‘s wise editorial direction, had the sense to publish this first novel by Louise Fitzhugh. Re-reading it more than forty years later, Harriet still speaks to me the way she did to so many writers, be they spies or novelists or as is true in most cases, both. The lessons I learned from Harriet when I first met her on the page still hold true for me today.

Readers don’t have to live the exact life that Harriet does in order to understand what her story is telling us. Writers will recognize themselves just as easily when they read Harriet’s story today as they did fifty years ago when the book was first published. Even though readers today may be recording their findings on an electronic tablet or publishing their observations on social media sites, the hard truths that Harriet learns as she goes from a spy taking notes to a writer writing stories remain the same.

If you want to be a writer, write down everything. Find out all you can, because life is hard enough even if you know a lot. Put down the truth in your notebooks, but don’t use it against your friends.

And as Ole Golly tells Harriet, gone is gone. Don’t try to hold on to people or lie down in your memories. Make stories from them.

Happy Anniversary, Harriet. May just as many readers be clinging to your hard won truths in 2064.

December 19, 2013

My Favorite Memoirs

So since I’ve been working on memoir pieces for the last four years and since I recently read this blog post on the impossibility of listing your favorite memoirs, I thought it was time to come up with my own list. After all, it’s the end of the year, the time of the BEST of the BEST lists. My favorite memoirs go back a lot farther than this last year, but here’s my short list in no particular order.

THE LIAR’S CLUB by Mary Karr

THE DUKE OF DECEPTION by Geoffrey Wolff

THIS BOY’S LIFE by Tobias Wolff

UNDER A WING by Reeve Lindbergh

DON’T LET’S GO TO THE DOGS TONIGHT by Alexandra Fuller

THE GLASS CASTLE by Jeannette Walls

STAY OF EXECUTION by Stewart Alsop (full disclosure, this author is my father)

MY FATHER’S FORTUNE by Michael Frayn

LIFESAVING by Judith Barrington (who also wrote WRITING THE MEMOIR, an excellent writer’s guide to the form)

ELSEWHERE by Richard Russo

THE CENTER OF THE UNIVERSE by Nancy Bachrach

CLASS by Geoffrey Douglas

TRUTH AND BEAUTY by Ann Patchett

RATTLEBONE by Maxine Clair

THE TIGER IN THE ATTIC by Edith Milton

MEMOIR OF THE BOOKIE’S SON by Sidney Offitt

Why do these pop up for me from my “memoir bookshelves”, the ones online and physically at home? Because there’s no whining in any of them. The emotional truth as they see it is told objectively with grace and often with humor. There are scenes in these books I will never forget.

Beth Kephart put it this way, “Look for authors who understand that the big questions in life can often be approached, assessed, and entered into through seemingly small and always carefully chosen details. Look for writers who recognize that chronology is not necessarily structure, that the unsaid matters as much as the said, that instant decrees and damning judgments are not nearly as interesting as thoughtful, and thoughtfully rounded, ideas. Look for authors who write humanely, who seek out loud, who open their worlds to you in ways that open you unto yourself.”

These are the memoir writers who have much to teach me and from whom I wish to learn.

December 11, 2013

We need the Authors Guild now more than ever….

Dear Friends and Fellow Writers:

Please read this letter from Richard Russo.

If you’re a working writer, you need to join the Authors Guild. The support they have given me over the years in reviewing my children’s book contracts and answering my royalty questions has made an enormous difference. They taught me what I needed to know to negotiate directly with publishers.

Because of the monumental changes that have occurred in the publishing industry in the last ten years, we need the Guild now more than ever as Mr. Russo tells us below.

If you’re a writer, join. If you’re not, please pass the word to your friends who are.

Elizabeth Winthrop

An Open Letter to My Fellow Authors

It’s all changing, right before our eyes. Not just publishing, but the writing life itself, our ability to make a living from authorship. Even in the best of times, which these are not, most writers have to supplement their writing incomes by teaching, or throwing up sheet-rock, or cage fighting. It wasn’t always so, but for the last two decades I’ve lived the life most writers dream of: I write novels and stories, as well as the occasional screenplay, and every now and then I hit the road for a week or two and give talks. In short, I’m one of the blessed, and not just in terms of my occupation. My health is good, my children grown, their educations paid for. I’m sixty-four, which sucks, but it also means that nothing that happens in publishing—for good or ill—is going to affect me nearly as much as it affects younger writers, especially those who haven’t made their names yet. Even if the e-price of my next novel is $1.99, I won’t have to go back to cage fighting.

Still, if it turns out that I’ve enjoyed the best the writing life has to offer, that those who follow, even the most brilliant, will have to settle for less, that won’t make me happy and I suspect it won’t cheer other writers who’ve been as fortunate as I. It’s these writers, in particular, that I’m addressing here. Not everyone believes, as I do, that the writing life is endangered by the downward pressure of e-book pricing, by the relentless, ongoing erosion of copyright protection, by the scorched-earth capitalism of companies like Google and Amazon, by spineless publishers who won’t stand up to them, by the “information wants to be free” crowd who believe that art should be cheap or free and treated as a commodity, by internet search engines who are all too happy to direct people to on-line sites that sell pirated (read “stolen”) books, and even by militant librarians who see no reason why they shouldn’t be able to “lend” our e-books without restriction. But those of us who are alarmed by these trends have a duty, I think, to defend and protect the writing life that’s been good to us, not just on behalf of younger writers who will not have our advantages if we don’t, but also on behalf of readers, whose imaginative lives will be diminished if authorship becomes untenable as a profession.

I know, I know. Some insist that there’s never been a better time to be an author. Self-publishing has democratized the process, they argue, and authors can now earn royalties of up to seventy percent, where once we had to settle for what traditional publishers told us was our share. Anecdotal evidence is marshaled in support of this view (statistical evidence to follow). Those of us who are alarmed, we’re told, are, well, alarmists. Time will tell who’s right, but surely it can’t be a good idea for writers to stand on the sidelines while our collective fate is decided by others. Especially when we consider who those others are. Entities like Google and Apple and Amazon are rich and powerful enough to influence governments, and every day they demonstrate their willingness to wield that enormous power. Books and authors are a tiny but not insignificant part of the larger battle being waged between these companies, a battleground that includes the movie, music, and newspaper industries. I think it’s fair to say that to a greater or lesser degree, those other industries have all gotten their asses kicked, just as we’re getting ours kicked now. And not just in the courts. Somehow, we’re even losing the war for hearts and minds. When we defend copyright, we’re seen as greedy. When we justly sue, we’re seen as litigious. When we attempt to defend the physical book and stores that sell them, we’re seen as Luddites. Our altruism, when we’re able to summon it, is too often seen as self-serving.

But here’s the thing. What the Apples and Googles and Amazons and Netflixes of the world all have in common (in addition to their quest for world domination), is that they’re all starved for content, and for that they need us. Which means we have a say in all this. Everything in the digital age may feel new and may seem to operate under new rules, but the conversation about the relationship between art and commerce is age-old, and artists must be part of it. To that end we’d do well to speak with one voice, though it’s here we demonstrate our greatest weakness. Writers are notoriously independent cusses, hard to wrangle. We spend our mostly solitary days filling up blank pieces of paper with words. We must like it that way, or we wouldn’t do it. But while it’s pretty to think that our odd way of life will endure, there’s no guarantee. The writing life is ours to defend. Protecting it also happens to be the mission of the Authors Guild, which I myself did not join until last year, when the light switch in my cave finally got tripped. Are you a member? If not, please consider becoming one. We’re badly outgunned and in need of reinforcements. If the writing life has done well by you, as it has by me, here’s your chance to return the favor. Do it now, because there’s such a thing as being too late.

Richard Russo

December 2013

July 7, 2013

Me and the NSA

I’m amused by the way everybody is freaked out about the NSA watching when we send an email and who we’re writing. I grew up in Washington, D.C., during the 1950s, the child of a political journalist.

My father, Stewart Alsop, with LBJ

We always assumed we were being watched, our phones tapped, our conversations recorded, our mail opened. My father often reported from Communist countries where, in his hotel room, he found taping devices behind the pictures, cameras in the mirrors, microphones in the flower arrangements. My uncle Joe  was entrapped by the KGB on a visit to Moscow in 1957 and surprised in bed with a man. Photos were taken and disseminated in Washington years later. In 1965, Uncle Joe accused LBJ of tapping his phone. In a fascinating conversation between LBJ and his attorney general, Nick Katzenbach, the two men discuss Uncle Joe and his sexual exploits. ( See a transcript in REACHING FOR GLORY by Michael Beschloss.) LBJ announces that he doesn’t believe in wiretapping, but even as he says it, you can imagine him leaning closer to the microphone he’d implanted in his own desk to make sure the reception was clear. He was taping himself for history. Speaking of taping, my father bet my brother that he couldn’t bug a dinner party without being discovered. My oldest brother, Joe, won the bet and went on to more nefarious capers. A friend of ours, whose father worked for the CIA, dropped a microphone down his family’s living room chimney. We ran a private telephone line through the Washington storm sewers so nobody could listen in to our conversations. Stealing other peoples’ secrets? That’s what you did.

was entrapped by the KGB on a visit to Moscow in 1957 and surprised in bed with a man. Photos were taken and disseminated in Washington years later. In 1965, Uncle Joe accused LBJ of tapping his phone. In a fascinating conversation between LBJ and his attorney general, Nick Katzenbach, the two men discuss Uncle Joe and his sexual exploits. ( See a transcript in REACHING FOR GLORY by Michael Beschloss.) LBJ announces that he doesn’t believe in wiretapping, but even as he says it, you can imagine him leaning closer to the microphone he’d implanted in his own desk to make sure the reception was clear. He was taping himself for history. Speaking of taping, my father bet my brother that he couldn’t bug a dinner party without being discovered. My oldest brother, Joe, won the bet and went on to more nefarious capers. A friend of ours, whose father worked for the CIA, dropped a microphone down his family’s living room chimney. We ran a private telephone line through the Washington storm sewers so nobody could listen in to our conversations. Stealing other peoples’ secrets? That’s what you did.

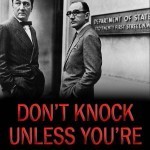

Fiction writers steal secrets in order to reveal them. I’d open lots of mail or listen to phone calls if it helped me develop a character. I certainly eavesdrop shamelessly. It’s a habit I developed when I was one of the children listening at the top of the stairs. It gave me memories revisited in DON’T KNOCK UNLESS YOU’RE BLEEDING, Growing up in Cold War Washington  and in an essay I wrote, entitled MY LIFE BEFORE TELEVISION, just published in an anthology BREAKFAST ON MARS and 37 Other Delectable Essays.

and in an essay I wrote, entitled MY LIFE BEFORE TELEVISION, just published in an anthology BREAKFAST ON MARS and 37 Other Delectable Essays.

And I know there will be more where those came from.

June 24, 2013

How I wrote an essay and lived to tell the tale…

I’ve never been very good at essays. I prefer to write stories with characters in them instead of essays where I feel I ought to come to some important conclusion. Even blog posts like this throw me. They don’t come easily. Perhaps it’s because my father, Stewart Alsop, was a columnist who wrote three 1,000 word essays a week for the Herald Tribune Syndicate and later in his career, the back page of Newsweek Magazine. He always came to important conclusions about politics and foreign affairs and government. I’ve never wanted to compete with him so, from the very beginning, I turned to fiction.

That meant that when a young editor called me up and asked me to submit an essay for an upcoming anthology to be published by Roaring Brook Press, I declined politely. More than once. But she was persistent. So I decided that I needed to stretch myself as a writer. I would give myself ONE DAY to write an essay. In the week leading up to my big day, I checked out collections of essays: Ian Frazier’s LAMENTATIONS OF THE FATHER, Calvin Trillin in the New Yorker , BEST AMERICAN ESSAYS. I read as many as I could. Then my big day came. I checked myself into a private writing room at my favorite library and I started writing.

In one day, I wrote the bare bones of my essay, MY LIFE BEFORE TELEVISION which is included in the just released anthology, BREAKFAST ON MARS AND 37 Other Delectable Essays edited by Rebecca Stern and Brad Wolfe. I was thrilled with my achievement, even happier with the excellent editing job and happiest at all the great attention the book is receiving. It’s received Starred Reviews and is a Publishers Weekly Best New Book of the Week “..a refreshing and useful tool for every middle- and high-school writing teacher to keep handy. Thirty-eight short essays—many humorous, some poignant—come from Sloane Crosley, Sarah Prineas, Ned Vizzini, Scott Westerfeld, Rita Williams-Garcia, and more.”

Hooray for me! I wrote an essay good enough to be included in an anthology with all these other talented authors. Teachers, grab a copy from your local bookstore. Maybe your students will learn earlier than I did how much fun essays can be.

March 7, 2013

The First of Three Mothers

I am losing three mothers this year.

My own mother died in November. One of my best “book mothers”, Nina Ignatowicz, the editor I’d worked with for forty years, died in January. And my other “book mother,” Margery Cuyler, a friend from college days and my other primary editor (The Castle in the Attic, The Battle for the Castle and many more) has announced she will be retiring at the end of 2013.

First, my biological mother. I decided to write the book I’ve just finished (first draft, on revision) about my mother’s childhood in Gibraltar and her life in London during the war because I didn’t want my mother to leave us with her stories untold. Her increasing dementia was taking her away from us inch by inch. I wanted to hold on to her somehow. A writer can do that with words.

Was my mother ever a child? She must have been, but it wasn’t until I was well into my fifties and my father had been dead for over twenty years, that I began to ask about her life. The stories that came spilling out of her, rich with specific detail and strong emotions, felt as if they had been dammed up for years in a deep pool of her memory…

In the last few years, she’s been telling people that I’m writing her autobiography. I don’t bother to correct her. It isn’t an autobiography, because of course, she’s not writing it. It’s not even a biography, because I’m in it too. The stories change because they’re coming through me. Another listener might have fastened on a different detail, seen some incident from a different angle. This book contains her memories, but I’m the one who’s choosing which story to hold up to the light first, and which one comes after that, and so on until they’ve all been told.

By telling her story, I’ve come to understand her better and isn’t that what every child wants? Why were you the way you were? Why didn’t you do it differently? It’s been an interesting and a painful exploration because some of the knowledge of her early tough years came too late for me to say I’m sorry, now I get it. Conversely, what I now know cannot necessarily explain or excuse some of the choices she made. While my memoir constitutes some sort of apology for the gaps between us, it also acknowledges that distance between parents and children is not only natural, but in fact inevitable and necessary.

My “book mothers”? Those stories in another post.