Colleen Anderson's Blog, page 6

February 24, 2019

Women in Horror: Tracy Fahey

[image error]

The Past is Always Present: New Music for Old Rituals

This is a story of folk horror and of its roots in much older tales. It’s a story of how these old, cautionary tales still cast long shadows in contemporary culture. And of course, it’s part of the story why I wrote my second collection, the nineteen tales of folk-horror that make up my second collection, New Music for Old Rituals (Black Shuck Books 2018).

[image error]

New Music For Old Rituals (Black Shuck Books 2018)

This collection grew organically from my own upbringing as a child in rural Ireland, where the very landscape was infused with myth and folklore. I grew up on the site of the great Irish saga of the Táin Bó Cúailnge halfway between two towns, Dundalk, where the Táin hero, Cuchulainn was born and Ardee, where he slew his best friend Ferdia at a pivotal battle−even my secondary school sits beside an ancient burial ground where mounds marked the site of Cuchulainn and his wife Emer’s graves.

But even more so, New Music for Old Rituals was influenced by the stories I grew up with, curses, stories of na Sidhe, the dark Irish fairies and their interactions with human, tales of jumping churches, of banshees, of curses and of graves cracked by a hungry Devil. These stories were told in my neighbourhood, within my family, and they formed the cornerstone of my childhood experience.

[image error]

The site of Wildgoose Lodge. Photograph © Tracy Fahey 2015

The first piece of short fiction I published in 2013, ‘Looking for Wildgoose Lodge,’ (in Hauntings, Hic Dragones Press) was based on a story originally told to me by my grandmother; a tale of a two hundred-year-old atrocity. I was fascinated by the idea of the persistence of memory in a small community, and the fact that these stories were still told. I was drawn to this topic by the fact that in folklore the past was always present−that these stories still operated strongly as cautionary tales that warned of the dangers of secrecy and of secret organisations, and the untrustworthiness of neighbours. I spent three years working on a memory project with these families and recording their variant stories of this event as part of my PhD thesis.

At the same time I was also researching the folklore and how it echoes through contemporary Irish art and literature, and have since published five academic essays on this topic in edited collections by Palgrave, Routledge, Peter Lang Publishing, Aguaplano, and Boydell and Brewer. However, this research kept inspiring new ideas for fresh fiction, and so in 2016 I started writing in earnest on a new collection that would focus on the survival of past narratives in contemporary Ireland.

[image error]

Cuchulainn, The Hound of Ulster, art by Jim Fitzpatrick

In putting together this collection, I’ve only obliquely referenced ‘real’ Irish folktales. I was more interested in the nature and character of folktales; how they seep upwards from the very landscape, how they’re mapped by real sites that act as portals to other worlds; dolmens, passage graves, fairy mounds. In 2015 I’d spent time armed with a copy of Tarquin Blake’s Haunted Ireland, visiting and photographing local spectral sites; many of these photographs would later act as triggers for some of the stories that I would write, most notably ‘The Green Road,’ ‘Graveyard of The Lost,’ and ‘The Black Dog.’

[image error]

The Black Dog. Photograph © Tracy Fahey 2015

I was conscious when writing of other contemporary Irish authors like Patrick McCabe, who creates evocative dark, small towns with a savage magic realism, and Peadar Ó Guilín whose dystopian novels are influenced by his erudite knowledge of Irish folklore. The stories that I wrote between 2016 and 2018 all feature the pervasive power of the past; how old, bitter stories ripple outwards and continue to shape our culture. Some reference the Irish fairies, but the tales that do so consider them in contemporary contexts; man-made fairy villages (‘The World’s More Full of Weeping’), children’s games (‘Under The Whitethorn’), burial rites (‘The Cillini’) and gender identity (‘The Changeling’). The collection also references modern Irish phenomena like ghost estates (‘Scarecrow, Scarecrow’) and the Celtic Tiger economy (‘What Lies Beneath’). What all stories do is consider the ties between the past and present, and how certain themes are both repetitive and timeless; ideas of loss, love, sacrifice, family, inheritance and transmission.

There were also two things that were important to me in writing this collection; I wanted it to have a strong female voice (most of the protagonists and narrators are women), and also that it represented the Irish lived experience of folklore as a continuum between past and present. The reason for this is that New Music for Old Rituals sits squarely within the canon of folk horror, a term that has gained popularity since the BBC4 TV series A History of Horror of 2010 where Mark Gatiss used it with reference to Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and also Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968) and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). Folk horror is also characterised in terms of contemporary contributions towards the genre: Ben Wheatley’s Kill List and A Field in England, Robert Eggers’ The VVitch (2015), David Bruckner’s The Ritual (2017), and The League of Gentlemen (1997-2017).

However, there are two interesting things to consider when looking at this genre since the 1960s: the fact it tends to be Anglo-centric and male-dominated. This isn’t to say that women are omitted in the canon−especially in terms of literature with Angela Carter’s marvellous The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories (1979) and Susan’s Cooper’s The Dark is Rising sequence (1965-77)−but there Carter’s contribution, as with so many other outstanding works by female writers like Margaret Atwood, Tanith Lee, Gemma Files, Kelly Link and Helen Oyeyemi tend to be categorised under the heading of ‘revisionist fairy tales.’ Not that there’s anything wrong with revisionist fairy tales−the rewriting and re-questioning of these forms is a valuable part of the feminist canon of writing−but it’s strange that many of these are not considered as folk horror. James Gent’s definition of folk horror could be used to sum up some remarkable short stories by women including Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’ or Angela Carter’s ‘Wolf Alice.’

Hermetically sealed (usually rural) communities; imagery of agriculture, fertility and the soil; modern man standing on the precipice of deeper, hidden, horrors and the friction that arises; a haunting of the present by the past; and the arrival of an innocent outsider drawn into this hinterland. (Gent 2017)

[image error]

The Cillini. Photograph © Tracy Fahey 2015

Women in Horror Month is more than just about celebrating the women who are or have been active in the field; it’s also about honestly examining whether female achievement is correctly attributed across horror. The horror genre−and the folk horror genre−is richest when it encompasses a breadth of diversity and experience−from across genders and nationalities.

I’m glad to see that recent folk horror collections; Green and Pleasant Land (2016, Black Shuck Books), The Fiends in The Furrows (2018, Nosetouch ress) and This Dreaming Isle (2018, Unsung Stories) all feature a very balanced number of contributions by outstanding female writers. I’m also delighted to see the accolades coming in for Alma Katsu’s The Hunger (2018), which draws upon oral folklore of The Dinner Party and ideas of the Wendigo, and Gwendolyn Kiste’s The Rust Maidens (2018), a meditation on urban folklore.

And of course, I’m very grateful to my publisher Steve J. Shaw of Black Shuck Books for taking a chance on my ode to Irish folk horror, Old Music for New Rituals, and to all who have bought, read and reviewed it. Folklore continues to evolve and to be part of our lived experience, and I’m proud to have offered a small reflection on it with this collection.

References

Gent, James. ‘Robin Hardy, The Wicker Man and Folk Horror.’ Etext at http://wearecult.rocks/robin-hardy-the-wicker-man-and-folk-horror. Last accessed 9.05, 29/06/2018.

[image error]Tracy Fahey is an Irish writer of Gothic fiction. In 2017, her debut collection The Unheimlich Manoeuvre was shortlisted for a British Fantasy Award. Two of her short stories were long listed by Ellen Datlow for honourable mentions in The Best Horror of the Year Volume 8. She is published in over twenty Irish, US and UK anthologies and her work has been reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement. Her first novel, The Girl in the Fort, was released by Fox Spirit Press in 2017. Her second collection, New Music for Old Rituals was published in 2018 by Black Shuck Books. Her website is at www.tracyfahey.com

February 23, 2019

Women in Horror: Caitlin Marceau

[image error]Canadian Caitlin Marceau talks about horror in film and a few Canadian authors of horror fiction today for Women in Horror Month.

Great Canadian Horror

When you think of great American horror authors, a myriad of names come to mind: Stephen King, Edgar Allan Poe, Anne Rice, Dean Koontz, Shirley Jackson… the list goes on and on. When we think of great British horror authors, there’s also no shortage of names: Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker, Clive Barker, M. R. James, Neil Gaiman, Susan Hill… you[image error] get the picture.

But how many popular Canadian horror authors can you come up with?

It’s okay if you need a moment to think about it, most people do.

In truth, there aren’t many Canadian horror authors who are as popular or internationally renowned as those from other English language countries. Australia has the likes of Angela Slater, Kirstyn McDermott, and Greig Beck, and even New Zealand has Maurice Gee, but when you mention Canadian horror most people stare into the distance and come up empty.

Although there are a few powerhouse names that can be found here in the great white [image error]Instagram.

February 22, 2019

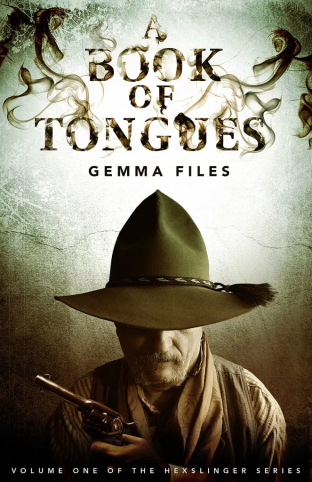

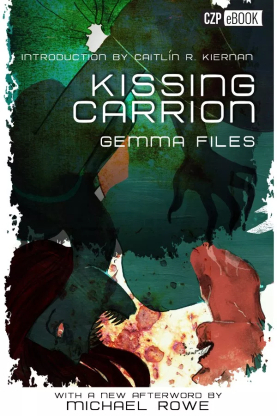

Women in Horror: Gemma Files

[image error]Award winning Canadian author Gemma Files talks about growing up, dealing with puberty and becoming a horror writer.

Women in Horror Month: Woman/Horror Writer

It took me a long time to think of myself as a woman, and getting my period at age ten and a half was part of that. As I blew straight through puberty over the next six months, it didn’t help my already awful social cred even a little: I was still angry, still “too smart” and still didn’t understand what made a person popular, except now I also had glasses, braces, pimples, cramps, my full height and breasts before anyone else, at a time when it was guaranteed to seem creepy rather than cool. Boys didn’t try to look down my shirt so much as they picked fights with me, while the girls I invited to my birthday party found a box of my maxi-pads and used them as impromptu decorations.

Which perhaps goes a way towards explaining why I soon decided that my gender had nothing much to recommend it overall, and nothing to do with me. I spent the next twelve years thinking of myself as a brain on top of a spine before blundering into a group of friends just as Aspergian as myself, one of whom I eventually married. And all of them liked fantasy and science fiction and comics, movies and music and role-playing games, fandom and collecting and various branches of academic study—which was great, because so did I. But out of all these people, I was pretty much the only one whose thoughts almost always tended (as Yukio Mishima so beautifully put it) to Night, and Death, and Blood. Out of all of them, I was the person who called myself a horror writer.

Which perhaps goes a way towards explaining why I soon decided that my gender had nothing much to recommend it overall, and nothing to do with me. I spent the next twelve years thinking of myself as a brain on top of a spine before blundering into a group of friends just as Aspergian as myself, one of whom I eventually married. And all of them liked fantasy and science fiction and comics, movies and music and role-playing games, fandom and collecting and various branches of academic study—which was great, because so did I. But out of all these people, I was pretty much the only one whose thoughts almost always tended (as Yukio Mishima so beautifully put it) to Night, and Death, and Blood. Out of all of them, I was the person who called myself a horror writer.

I was a woman as well, though, and (since I’m cis) will always remain one. I was a woman when I fixated on vampires and studied black magic, a woman when I read my way through Tanith Lee’s back catalogue at Toronto’s Judith Merrill Collection or collected Fangoria magazine to educate myself about directors I idolized (like David Cronenberg, weird and Canadian!), a woman when I applied for my first film critic gig by writing unsolicited reviews of Silence of the Lambs and Pumpkinhead. So when I first started to send out the horror stories I wrote, part of the dreadfulness of embodiment I concentrated on very much had to do with the specific ins and outs of my own female flesh—and just describing things like menstruation, cunnilingus or childbirth in detail was enough to disgust and terrify, I soon found, especially when playing to what most people still assume is a mainly-male audience.

Back in the early 1990s, the genre was full of extremity, Splatterpunk, “erotic horror”…people were always trying to push the envelope, to deliberately shock and offend, and where that automatically seemed to take a lot of authors’ minds was back to the female body, but always from the outside: as a prop, an artefact, a plot twist. Skimming through my local bookstore’s horror section, I mainly saw stuff that focused on the destruction and befoulment of people who looked like me, our inevitable and luxurious transmutation from sugar, spice and everything nice to a rotting corpse with a vagina full of teeth. When I sold five stories to The Hunger (an erotic horror anthology show produced by Tony and Ridley Scott for Showtime, which ran from 1997 to 2000 and shot out of Montreal), I got to visit the production office, where the writers’ room had a list of rules pinned up on the wall. I can’t remember all of them, but “If a woman gets naked, she’s evil” was definitely number one.

Though I’d cut my literary teeth on Stephen King and Peter Straub, like almost everyone [image error]else in my generation, the people I increasingly drew direct inspiration from were exceptions rather than rules: non-default in terms of gender, sexuality and outlook. They were body-horror poets like Clive Barker, Caitlín R. Kiernan, Melanie Tem, Kathe Koja and Poppy Z. Brite; they were decadents from the underside of the 1980s horror boom like Michael McDowell and Douglas Clegg (both gay, I later found out), or forgotten mistresses from earlier ages like Marjorie Bowen and Vernon Lee, along with all the other ladies published in Virago Press’s two collections of ghost stories. And slowly but surely, I realized I was attracted to these people because the things which fascinated me also fascinated them. I’d never been mainstream, not in my life—but was that because I personally was singular, perverse, different from the norm? Or was it possible that all people who identified as different from the norm were just more likely to have interests which crossed over with mine, women very much included?

And at every point on this journey, I got asked the exact same series of questions: Why horror, and why horror for me, a woman? Why not write something else, something less upsetting and declassé, something less firmly located at the intersection of Gore and Porno Streets? What could I possibly get out of it, or assume anyone else would get out of it?

Here’s a sad fact: when you love a thing that supposedly only men love but you’re not “a man”…by which I mean the same limiting, parodic mainstream image of what a straight cis white male should be that makes even straight cis white males sometimes doubt their ability to live up (or down) to it…it makes it hard to love yourself. When the only image of someone like you you’re likely to trip across inside that thing you love is a joke, a sidekick, a monster or a dead body, it makes it hard for you as a person who loves horror and wants everything any other person who loves horror wants—transformation and apotheosis, power in darkness, revelry and revenge, (fictional) death to your enemies—to want to have anything to do with those characters, that gender, yourself. It makes you want to be sexless, a brain on a spine, a ghost. It makes you want to be a man.

But here’s how things have changed since I started writing horror, thankfully: much though I enjoy writing from their POV (particularly while watching them have sex with each other), I don’t actually want to be a man anymore. I want to be me. Because, as has always been the case, horror really is for women too, and queer people, and diverse people of all kinds—the whole intersectional non-default brigade. It doesn’t mean we hate ourselves by loving it, and it doesn’t have make us hate ourselves to love it, either. Because it shows us we can love ourselves all the better by not only embracing our own inherently monstrous-coded differences from “the norm,” but by understanding that the greatest trick mainstream culture ever played was convincing us there really was a norm to deviate from, in the first place.

But here’s how things have changed since I started writing horror, thankfully: much though I enjoy writing from their POV (particularly while watching them have sex with each other), I don’t actually want to be a man anymore. I want to be me. Because, as has always been the case, horror really is for women too, and queer people, and diverse people of all kinds—the whole intersectional non-default brigade. It doesn’t mean we hate ourselves by loving it, and it doesn’t have make us hate ourselves to love it, either. Because it shows us we can love ourselves all the better by not only embracing our own inherently monstrous-coded differences from “the norm,” but by understanding that the greatest trick mainstream culture ever played was convincing us there really was a norm to deviate from, in the first place.

Horror is for everyone, it turns out, because everyone’s equally afraid of their body, the universe, each other and themselves—because we all love things, and know we’re going to lose them; because we all know we’re going to die, and we all hate it. Because we all know this is going nowhere good, much as we may hope like hell otherwise. Horror is for everyone, male, female or otherwise, because it’s the genre that teaches us not to trust blindly, that behind every pretty lie is an uncomfortable yet freeing truth. That all of us could be monsters, and as long we let ourselves be aware of that fact, we also know we don’t have to be. That just as the grave has room enough for all of us, the grave’s rim has more than enough space for everybody who wants to take their turn donning masks and telling stories in the dark.

So many people just like me, all getting the same thing out of what I love that I do. It took me a long time to think of myself as a woman, far longer than it did for me to think of myself as a horror writer. Yet here I am.

In fact…I’m here all year.

February 21, 2019

Women in Horror: Sarah Read

[image error]

Today, Canadian Sarah Read talks about creepy crawlies and their unjust bad rap. From Shelob to Spider-Man, spiders play a significant role in fiction and our homes.

Cellar Spiders: Your Secret Best Friends

[image error]Whenever I finish a new story, the first thing my reader friends usually ask is, “Are there spiders in this one?” Because, yeah, usually. I have a bit of a spider reputation. I love them and I think our culture has unjustly vilified them. They often feature as protagonists or positive symbols in my work, as they have in much of mythology throughout the world. My recently released novel, The Bone Weaver’s Orchard features a lot of spiders (and other crawlies) as well as a protagonist who loves them. Like Charley Winslow in my book, I keep a menagerie of spiders, though mine roam freely through my house. My basement is full of Cellar Spiders−thousands of them.

Cellar Spiders, often referred to as Daddy Long Legs, are members of the Pholcidae family. They are often found hanging upside down in their non-sticky webs in cool, damp places like cellars, attics, under sinks, or in any tucked-away corner of your home. Their long, spindly legs give them a definite creep factor, but these small heroes have received a bad rap from generations of misconceptions and urban myths.

Spiders play a major role in creation myths, no doubt inspired by their web-weaving. [image error]There are benevolent spider gods and goddesses in Sumerian myths, in the ancient Islamic oral traditions, in African and Native American legends. For some indigenous Australian tribes, a Lord Spider created the entire universe. From the West African Ananse to the Hopi Spider Grandmother, spiders play a key role in our storytelling. Even our language for story is inspired by them−spinning and weaving tales and our webs of deceptions. Despite our modern discomfort with spiders, they still turn up as heroes in our stories. Charlotte’s Web and Spider-Man are as iconic to us as Arachne was to the Greeks. So while the spider seems to feature more often these days as a monster or a figure to induce fear in an audience, that wasn’t always the case. They deserve to reclaim their old reputation as clever, kind, and creative. The spiders lurking around your home and garden are certainly all those things, and most of them aren’t dangerous.

One of the common myths about Cellar Spiders is that they have the most potent venom in the world, but that their mouth parts are too small or weak to bite you. I have good news and bad news about that. The good news is that their venom has been shown to be very mild and definitely not at all harmful to humans. So, ease your mind on that. The bad news is that they definitely can bite you, if they want to. For an additional bit of good news: they don’t want to. It’s very rare to hear of anyone being bitten by a Cellar Spider−they are evasive, not aggressive. If their web is disturbed, they simply drop to the floor and skitter away. The only times they have been shown to bite is if they are cornered, trapped, and grabbed. Since most people don’t go around grabbing spiders with their bare hands, this isn’t a problem that arises often. If a Cellar Spider bites you, you probably deserved it. And, you’ll live.

There are better reasons, however, for leaving Cellar Spiders be. They are the best [image error]natural predators for the things you hate even more than you hate Cellar Spiders. They love to snack on centipedes, recluses, black widows−they eat the things you definitely don’t want in your house. They’ll even cut down on the dreaded mosquitoes. They keep their webs tidy and remove their leftovers, so you won’t even see their webs most of the time. That’s better than can be said for any human I’ve ever lived with.

While I’m sure it can be said that most people would prefer to have no spindle-legged critters in their homes, the fact remains that you are going to have them. Your preferences matter not to nature. But if you’re going to have leggy housemates, these are the ones you want. They are ultimately beneficial and not at all dangerous. So the next time you notice your basement ceiling is bristling with long-legged beasties, put down the broom and think for a moment. What is it in your basement that feeds such a [image error]population of predators? And would you want such things taking over unchecked? Then give these lithe-limbed ladies a salute and allow them to serve their role as stewards of the dark and dank spaces of the house.

Sarah Read is a dark fiction writer who lives in an old house full of spiders. Her debut novel The Bone Weaver’s Orchard, also full of spiders, has just been released from Trepidatio Publishing. You can keep up with her work at www.inkwellmonster.wordpress.com.

February 20, 2019

Women in Horror: Bianca Pheasant

[image error]Bianca Pheasant is a South African author who will talk about the beauty of horror for Women in Horror Month.

The Beauty of Horror

Horror, it’s such a beautiful thing. Most individuals would claim they do their best to avoid it as far as possible but deep in their souls, they know they want it, even if it was just a pinch. In fact, we not only want it, we need it.

When I was younger, I could not wait for the next Nightmare on Elm Street movie or the [image error]newest horror novel. Not only did I eat it up like cake, I lived for it. I must have been ten or eleven when I read Tommyknockers−my first Stephen King novel. After that, I discovered Dean R. Koontz’s The Bad Place. Then I started writing. And of course, it was only natural that I would write books dripping with horror, aimed to terrify.

I’ve often been asked why I don’t write “happier” stories and why my work is always so bloody and depressing. My answer is always… “Because that’s what my readers want!” Besides… books about how lonely woman meets hunky man with a dark past and never-ending issues are just plain boring.

The reason I love writing in the horror genre is because I never have to walk on eggshells when I write. I don’t have to be conservative or mindful. The words flowing from my imagination need not be filtered for fear of being too gory or crass because the demand for exactly those things are high.

But that’s not all.[image error]

I believe that every person has two sides. The one side we show to the world. The other, well… this is the one we hide. We push it so deep into our psyches we sometimes forget it exists. We chain it like a rabid beast, lock it up and swallow the key.

The problem with that is that those bars rust and grow frail. That is when I write my best horror work. Once the beast breaks free, I can delve into the darkest corners of my mind and not be afraid. The thoughts and ideas I’m expected to hide ignite every brain cell concealed within my skull and as fingertips marry keyboard, the beast…my beast, isset free.

[image error]Being a writer gives me the ability to give the darkest fantasies of my mind a voice and watch them as they come to life right in front of me. I set them free and they write the story for me. Trust me when I say the author is NOT always behind the steering wheel. We are string puppets manipulated by the fictional, and sometimes not so fictional, characters in our heads.

Once they are set into motion, I sit and marvel at the chaos they create. Like the infamous Dr Hannibal Lector, I’ll feel proud because I know they are my design.

The best part of being a writer of terrible things is the research. I once did a whole study on how to poison a grown man using hemlock extract and how much Acepromazine it takes to knock him out without killing him. (Acepromazine is a tranquilizer used on horses, by the way.)

If someone had to look at my browsing history without knowing that I write weird and [image error]creepy tales, I can only imagine the suspicion, and maybe even fear, running through their minds.

Think about it for a second…

You’re having wine with this amazing couple you met a week ago. Expecting an important email, you ask if you can use the laptop laying on the kitchen counter. Your hostess smiles and tells you, “Be my guest, dear.”

You check your mail and out of curiosity you check the browsing history and finds this:

[image error](Yes, that is my actual browsing history)

After a few minutes of awkward silence, you excuse yourself, never to enter that house again.

But… if you knew the user of the laptop was actually a horror writer, the weird subjects in the browsing history would not seem so scary anymore.

This brings me back to the point I tried to make earlier.

We love horror. We enjoy being terrified by the unknown and whether we like to admit it or not, we cannot get enough of the dark and twisted minds of the legendary fathers of horror like Stephen King, Edgar Allan Poe and Robert Bloch.

These are the people who twists our dreams into nightmares. They unsettle our comfort zones and tickle the monsters tucked far away in our subconscious, agitating them until they break free from the rusty old cages we rely on to keep them at bay.

As readers, we feed the imaginary evils we consume from the pages of novels written by these authors to our captive monsters. But as writers, we are able to share our dark creativity with the world without fear of being ridiculed, judged or burnt at the stake for being suspected of practicing witchcraft. I’m sure if this was the 16th or 17th century, no horror writer would have dared to pen their thoughts onto paper.

Can you imagine Edgar Allan Poe as a writer of romantic poetry?

So, dear reader, next time you read a novel filled with bloodlust and unexplained horrors, take a minute to realize one thing… every scene making you experience the slightest bit of discomfort… those are the mirror images of our minds. Know that we freed the untamed beasts so your need for horror could be fulfilled.

We expose our deepest and darkest fantasies for your entertainment and as our fingers dance over the keyboard in a tango of horrific beauty… we love every word, syllable and phrase.

[image error]Bianca Pheasant is an aspiring new author trying to make her mark in a world filled with great ones. She lives in South Africa with her husband of ten years, only daughter and her trusted Staffordshire terrier. She has a fascination with crime and murder mysteries, the criminal mind, reptiles, arachnids and of course tattoos. She is a humble being who detests writing biographies about herself and dislikes photos of herself even more. www.biancapheasant.co.za. Check out Bianca’s Facebook page as well as her audiobooks and E-books.

February 19, 2019

Women in Horror: Arinn Dembo

[image error]Arinn Dembo, game and fiction writer, hails from Canada. Today, for Women in Horror Month she talks about a very special house.

Haunting the House

Horror did not just spring up out the Earth like a mushroom. Horror was built by human hands. And I would argue that those hands belonged to women.

Women came to the Lonely Place of Dying and called it home. Isn’t Death always a female realm the world over–ruled by a pretty young queen and her doting husband? There is a reason for that, woven into human flesh and bone. They call it “the maternal mortality bump” for a reason.

[image error]

Illustration from Thasaidon: Tales of Death Magick by Clark Ashton Smith. Edited and annotated by Arinn Dembo, Kthonia Press

Our ancestors dug a foundation deep into black bedrock.

They built the walls from shipwreck timber and hanging trees.

They dug a cellar deep enough to keep wine and potatoes, and to soak up screams.

They hung windows that blankly reflected the bone white sky, and mirrors that reflected your true face.

In the warmth of evening firelight, women would spin thread and pass the time with ancient, bloody tales–the kind that we share when the children have gone to bed.

Men who smile, and flatter, and kiss, and kill.

Unlucky girls who marry a man in black.

Mad women. Mad men. Damned priests and cruel governesses. Girls who said “yes” to the wrong offer of employment. The unwanted…abandoned. The unloved…locked in freezing garrets or hurled bodily down the well.

In the 18th century parlors and the libraries, young women sat and scratched away with busy pens, writing the most popular novels of the age. Ann (Radcliffe) was the reigning champion, of course—the best-paid writer in the English language during her time, just as J.K. Rowling is today.

[image error]

“Proteans Attack” – Illustration from Black Section: The Complete Files, by Kerberos Productions

Ann retold those old stories, gave them winsome young heroines with pretty faces and salted the old meat with a dash of romance. She grew rich on her tales, traveled the world with a pretty husband and fine clothes. And with her wealth she plastered the bare beams and dark walls of the House with new paper, laid carpets in the drawing room, hung curtains to discourage the curious.

The stories of that generation are still being told today, over and over. I can turn to any movie channel and find a dozen stories about women fighting for their lives and their families against the forces of psychopathy and abuse. And those tales are not “thrillers” or “psychological dramas” or what-have-you. They are Horror, grounded in fears that still have teeth. Because women in any generation have to live with the same threats: when passion fades and love sours, women DIE.

Men have walled off those old rooms, of course. The only part of the house that they want to call “Horror” is the part they have appropriated for themselves. And they actually believe they can keep women out! They try to make us unwelcome. (Unless, of course, they need a limp doll to play the Victim in one their pathetic little puppet shows…then our bodies will do.)

But it was Mary (Shelley) who built the new wing that they strut around in today. She lit the first gas lamps, and split the night with the crackle of electricity and the shrieks of rebirth.

Just as Shirley (Jackson) is the reason that stones rain from the sky, that houses eat their owners and knives whistle through the air with no hand to hurl them.

There is no age or era of horror as a genre that you cannot find female excellence. The house of Horror is built from the flesh and bone and blood and sweat and tears of women. Small wonder, then, that women remain loyal to the House, and have never left it…no matter how male dominated and obnoxious the mainstream offerings of Horror have become.

Female readers still buy the books. Female viewers still come to the theatre. They still turn out to honor their great-grandmothers and the old ways. They come to watch the Final Girls run screaming through a Man’s World, and those footfalls echo through eternity.

Why?

[image error]

ICHTHYS – An Easter tale of horror in the catacombs of ancient Rome

Because every woman who exists on Earth today is the descendant of a Final Girl, even if her struggle is lost to memory.

Nothing has changed. The women in the stories still emerge alive. Bloodied and traumatized, crippled by loss and cynicism, older and wiser…but alive.

I would argue that the reason that women never abandon Horror is simple: Horror belongs to us.

Because Horror is the story of women’s lives.

Horror is the experience of being female in the world.

Horror is the genre where hypervigilance is a female super power and can be a guarantee of survival. Where Trauma becomes an asset, not a liability.

Horror is the genre where boundaries crossed result in the lethal consequences that women have always longed to see.

Horror is the school where we take night classes in Know Thy Enemy.

Women built this House. And we will always haunt this house.

We still prowl the oldest depths of the ancestral manse, telling stories of the poisons that leach from bad faith and black hearts.

We still kick open the doors that men try to nail shut and shout our stories into the room—even though we are seldom greeted with applause.

And women are still building new wings to this house. Sometimes the sounds that come from those new halls are unearthly, full of pain and terror…but sometimes they are orgiastic. In this brave new age, women are not always shy about pleasure as well as pain.

Women in Horror Month is a time of celebration, but I also see it as a time of truth and reconciliation. And really, if this is the only time of the year that you SEE Women in Horror…it’s because you know exactly Jack and Squat about Horror.

And Jack left town.

[image error]

Fort Zombie 2 – The royalty of Erebos. Queen Zombie concept art from Fort Zombie 2, by Kerberos Productions.

Arinn Dembo is a professional writer and game developer living and working in Vancouver BC. She was the lead writer of Fort Zombie, the cult classic indie game which spawned a legion of zombie base-building and defense titles, and has brought a little extra creepiness to many other PC games for her home studio, Kerberos Productions. Her short fiction has appeared in HP Lovecraft’s Magazine of Horror, F & SF, Mad Scientist Journal, Lamp Light, Deep Magic and a number of horror anthologies, including Gods, Memes and Monsters, She Walks in Shadows, and What October Brings. To sample her short fiction and poetry, you can try her single-author collection, Monsoon and Other Stories, or grab her horror one-shot ICHTHYS.

February 18, 2019

Women in Horror: Sara C. Walker

[image error]Today, for Women in Horror Month, we’re back to Canada with Sara C. Walker who gives a list of some inspiring female authors and Canadian writers who do science fiction horror.

[image error]

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is an early example of SF horror.

When asked to name a woman writer with stories at the intersection of horror and science fiction, Mary Shelley is first to come to mind. Author of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, originally published in 1818, Shelley is credited for writing the first science fiction story, though it’s often forgotten the story was intended to be horror. With that story, the sub-genre science fiction horror was born.

Science fiction horror ponders the current state of science and projects all the worst ways things could go wrong. As in Frankenstein, the true monsters of science fiction horror are human. From horrible dystopian societies to nightmare post-apocalyptic landscapes to brutal experimentation in the name of science, the stories are varied but also seek to answer the same question of every horror movie: who will survive?

Two hundred years since Mary Shelley’s creation, the genre crossing is a fertile playground for Canadian women writers, and while there are plenty of short stories that fit the science fiction horror genre, here are several suggestions for novel-length works to keep you up at night. This list is by no means exhaustive but is meant as a beginner’s guide.

[image error]

Real life SF horror–cancer ad from the 1800s

When looking for Canadian women who write science fiction horror, the first to come to mind is Margaret Atwood, specifically The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985, which has been adapted into a film, an opera, and now an HBO series, airing since 2017. This dystopian story imagines a pretty horrific future for women.

Ten years ago, the Canadian documentary Pretty Bloody: The Women of Horror interviewed actors and producers in the genre, along with Tanya Huff and Nancy Kilpatrick, two of Canada’s top horror writers. Huff’s contemporary vampire series was turned into Blood Ties, a television show that aired in 2007, but Huff also writes military science fiction series with a female protagonist—start with Valor’s Choice (DAW, 2000). Kilpatrick is also known for her vampire series, Thrones of Blood, but she also writes science fiction horror, as in Eternal City (Five Star, 2003).

Well known for her Otherworld series, especially her first novel, Bitten (Vintage Canada, 2009), which became a television show for three seasons in 2014 to 2016, Kelley Armstrong also dabbles in science fiction horror. The Darkness Rising series, beginning with The Gathering (Doubleday Canada, 2012), is a trilogy in which the main character, who lives in a medical-research town, finds strange things happening, beginning with the drowning of the swim team captain. Armstrong is also brilliant at writing psychological thrillers that will scare your pants off. Just try reading the beginning of Omens (Random House, 2013) or Exit Strategy (Seal Books, 2010).

Author Ada Hoffman’s novel The Outside, a science fiction horror, is due to be published June 2019 by Angry Robot. Hailed as “fast-paced, mind-bending Big Idea science fiction, with a touch of Lovecraftian horror”, The Outside features cyborg servants, a heretic scientist, and an autistic protagonist.

[image error]

The Handmaid’s Tale, base off of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel.

I do love Frankenstein, The Handmaid’s Tale, and stories that seek to show us what future might come of our choices, but my true love is for urban fantasy, a genre that’s a sibling to horror as both have roots in urban myths. So, with that in mind, I have one more reading suggestion for urban fantasy that fringes on horror, although this one leans more toward fantasy than science fiction.

These days she lives in Los Angeles and is more known for being the ex-wife of Elon Musk, however, Justine Musk is from Peterborough, Ontario and wrote horror back in 2005 with her first book, BloodAngel. The sequel was released in 2008, Lord of Bones (both published by ROC, in imprint of Penguin Books). We’re still waiting for more books from Musk.

[image error]Sara C. Walker writes fiction, usually urban fantasy, from short stories to novels. “True Nature” can be found in Alice Unbound: Beyond Wonderland (Exile Editions, ed. Colleen Anderson) and “If Wishes Were Pennies” in Canadian Creatures (Schreyer Ink Publishing, ed. Casia Schreyer). Forthcoming stories include “Stag and Storm” in Canadian Dreadful (Dark Dragon Press, ed. David Tocher) and “Call of the Ash” in Not Just A Pretty Face (Dead Light Publishing). She’s edited two anthologies of stories set in the Kawartha Lakes. When not writing, she works at a library and is always ready to give reading suggestions. You can find out more at www.sarawalker.ca.

February 17, 2019

Women in Horror: Halli Lilburn

[image error]Halli Lilburn, author and editor, speaks about what makes horror addictive.

Halli on Horror

Horror has its perks. A rush of hormones and adrenaline is addictive. The fight or flight mechanism in our brain is activated without ever being in danger. A good jump-scare is equal to extreme sports. But if you analyze the underlying conflicts behind monster versus man, the message can continue to disturb you for months and even years.

[image error]My parents wouldn’t allow me to go to a friend’s and watch Poltergeist, so I snuck out. I was thirteen. Curiosity and rebellion were my motivators. Mostly curiosity. I wanted to know what happened to human beings when their souls became corrupted and what kind of damage could they do to the living. I learned that it didn’t take much for a soul to cross the line from human to monster. It was the first time a show gave me nightmares. The morbidity rate on and off screen proved the truth of the rumors that demons had cursed the set. One actress was strangled to death by an ex-boyfriend, and the main character also died of mysterious health complications. I will never watch those movies again. The idea of retribution from beyond the grave will never not be scary. Thirteen is a very vulnerable time for a developing brain.

I am a vivid dreamer. Could be inherited from my dad or could be the anti-depressants [image error]I’m taking. Probably both. When people ask me where I get my bizarre ideas the answer is usually a nightmare. And the more outlandish the better. In horror, a writer can get away with anything. In my story Hidden Twin I found a way to make one body rip apart to find another body inside it like Donna in Poltergeist III (spoilers).

Still, there are areas in the genre that I avoid: (living) serial killers and body mashing are not my cup of tea. The thrill of witnessing a murder is petrifying but once you are dead, it’s over. The stories that get to me are the hauntings; images that churn in your mind over and over for years, being trapped inside your mind, not knowing what is real, losing control of your sanity. Ghosts are especially convincing when they reach out to their families for help, but their method of communication so cryptic it fails. When the dead stick around the living are bound to get hurt. Some examples include The Others, Sixth Sense, Delirium, and Haunting of Hill House. Like I said, if it gives me nightmares, it is well written.

SKULL SPEAK

A skull is what I see through

Through my hollow eyes

A skull is what I speak through

With chattering teeth

Always smiling

With no lips it’s impossible not to

A ribcage is what I love through

It is cold here in your heart

Can you find a way to love me?

The skeleton sits on my shelf

A corpse of me

Sporting a felt hat and smiling

Always smiling

Showing teeth in a carefree, neurotic way

“You are obsessed with me” it laughs

I tap its tiny noggin

I let you take up precious space on my shelf

Precious space meant for books.

It replied, “Ah, but the stories I could tell.”

[image error]Halli Lilburn writes speculative, sci-fi and poetry, but she always tries to spice it up with something horrific. Her most recent releases include stories in anthologies: We Shall be Monsters by Renaissance Press, Tesseracts 22: Alchemy and Artifacts by Edge Science Fiction and Fantasy. She is a freelance editor with essentialedits.ca and you can read more at her blog.

February 16, 2019

Women in Horror: Sara Townsend

Tod [image error]

Today we’re back in the UK for Women in Horror Month, where Sara Jayne Townsend talks about how she discovered horror and what draws her in.

WHY HORROR?

I was 13 years old when I discovered horror. Before then, I was scared of anything remotely creepy. But something changes in you when you hit puberty, and it’s not just about all the previously undiscovered angst coming out. That year, I picked up Stephen King’s Different Seasons while browsing in the school library. I liked it so much I went looking for more books by the same author and came across Carrie. After that, I was hooked.

The same year, my English teacher gave the class an assignment to write a horror story. [image error]Mine was about ten teenagers who went on a camping trip in a remote field and unearthed an ancient evil that possessed some of them, who then went around murdering the others. I really enjoyed writing it, and the teacher seemed to like it as well (she gave me an A+). It was something of a flawed story, but I was only 13 and had a lot to learn about the craft of writing.

That was 36 years ago, and I’ve been writing horror ever since. Over the years I’ve had many people ask some variation of the same question: “What’s a nice girl like you doing writing such nasty stories?”

So what is it about horror that’s so fascinating? I’ve asked myself the same question several times. Part of it is about exploring the dark nature of humanity. I am not interested in stories about people discovering love and living happy every after. I am much more interested in writing, and reading, about the darkness in people’s souls. What makes someone take the life of a fellow human being? The majority of people can’t imagine doing this, and yet it happens in our world, every day. Serial killers are fascinating to me because I want to understand what makes them do what they do. Is it some misfiring synapses in their b[image error]rain that makes them want to kill people? Or is it that such people are truly born evil?

Part of the appeal of horror on a personal level is being able to exorcise one’s own demons. I have certain recurring themes that seem to pop up in a lot of my stories−isolation; loneliness; despair. These seem to represent my own inner demons, and writing about them helps me to find a way to externalise them, and come to terms with them.

Another aspect of horror writing is escapism. A lot of readers like fantasy because it allows them to escape to a fantastical land of magic and strange and marvellous creatures, and a world that seems far more appealing than the one they live in. In horror, the reader escapes to a much darker world, of monsters and evil entities. [image error]Sometimes it puts your own problems into perspective. If you are reading a story about a world where a plague has wiped out all of humanity, and the few survivors face a daily battle of survival against brain-eating zombies, your own everyday worries seem somewhat insignificant in comparison.

And then of course there is the element of fear. We all like to be scared, but we much prefer to do it in a controlled environment, where we know the threat isn’t really real. That’s why people like roller coasters. The ride might be scary, but when it’s over you get off and the fear goes away. The same thing happens when you finish a scary book, although a really scary book might stay with you for a few days after you finish reading it. If I can do that to a reader, then I’ve done my job as a horror writer.

For all of these reasons, I love horror. I deal with my own fears by re-imagining them onto the page. And if I can write something that gives you nightmares–well, I’d take that as a compliment.

[image error]Sara Jayne Townsend is a UK-based writer, and someone tends to die a horrible death in all of her stories. She lives in Surrey with two cats and her guitarist husband Chris. She is author of several horror novels, the latest one being Outpost H311, the story of an oil exploration team who crashland on a remote island in the arctic to discover a hidden base that is hiding some sinister secrets.

Learn more about Sara and her writing at her website and her blog. You can also follow her on Twitter and Goodreads, and buy her books from Amazon UK and Amazon US.

February 15, 2019

Women in Horror: Colleen Anderson

[image error]It’s the ides of February. Well technically, that would be true possibly every four years, but it is halfway through the month and there are still many other women in horror to showcase. I would be remiss if I left myself out of the Women in Horror Month. So I too will talk about how I stumbled upon horror.

[image error]

Available on Amazon

Like many of the people who have already posted, The Haunting of Hill House and The Lottery were stories that stayed with me but I really don’t think I read them when I was a child. (And I have to mention the very good TV series of The Haunting of Hill House.) Most likely I watched these as a teenager. My first brush with horror was earlier with movies though. Not so much Dracula for me, though I do remember Frankenstein. When I was about six or seven my parents fought so badly that my mother would bundle us in jammies into the car and off to the drive-in we would go. The House of Seven Gables and The Fall of the House of Usher with Vincent Price, another king of horror, are forever conflated into one movie for me. I was that young and my mother certainly didn’t seemed worried about our young minds being warped.

Those two movies where Vincent’s character pickaxes his sister and buries her in the walls (or under the floors) stuck with me, along with the first nightmare I remember at age six. After that, the endless recycling of The Twilight Zone and the Outer Limits coupled with reading Edgar Allan Poe and Ray Bradbury made me who I am today.

[image error]

The Beauty of Death contains “Season’s End”

While I always liked the weird I was not a fan of horror. I detested most horror and gore movies. Slasher and murderer thrillers were not and still aren’t really my cup of tea. But the strange is and always has been, and that may be reflected more in the shows I watched and books I read.

When it came to writing, I was writing fantasy and SF. I wasn’t writing horror. I was a member of SFWA for a long time before I even knew of the Horror Writers Association (HWA). But I found stories I sent to magazines of SF or fantasy would be rejected with a note that they didn’t do horror. I was confused; maybe I still am, but my stories didn’t seem scary to me. Of course, they came from my mind so I knew where they were going.

[image error]

Colleen’s launch for A Body of Work takes place Feb. 23 at The Heatley.

Somewhere along the way I started to submit to some of the darker markets and like the sun setting on the longest day, I finally figured out that I sold more stories if I went darker. I have written a few truly terrifying depictions of horror in the gore sense, such as my flash piece “Amuse Bouche,” but while it was an exercise for me, it wasn’t where my heart lay. A writer friend once asked, “What theme are you exploring? We all explore a theme.” Hers were animals. Another writer’s was children…

I never thought I explored one theme until I put together my first collection of fiction Embers Amongst the Fallen. At that point, it became clear that I do morality tales. Not all of them but there is often a disturbing moral dilemma that a character must face (“The Healer’s Touch,” “An Ember Amongst the Fallen,” “Season’s End,” “Hold Back the Night”). In that sense, as opposed to the “other” outside of you invading your sanctity of life or home, it is the “other” inside. What deals with the devil will a character make to save something dear? I find that extremely interesting and personal, something to which we can all relate.

[image error]

Alice Unbound contains 22 speculative stories and poems inspired by the world and character of Lewis Carroll.

As with many of the writers here, we have a fascination with vampires, or werewolves, or creepy crawlies, or disturbing dolls, or clowns, or the dark, or subterranean depths or things hidden in fog or water or space. Just a readers do. It is as old as humankind–that fear and need to conquer it, and an intense curiosity about the unknown and the strange.

I have written several stories that also explore the psychopath/sociopath (modern studies don’t really distinguish between the two) intellect. The mind encased in a human body where that the person doesn’t think like a regular human. It is alien. I’ve look at aspects of this mind in such stories as “Exegesis of the Insecta Apocrypha,” “Sins of the Father,” “The Book With No End,” and “Gingerbread People.” The first was one story that very much disturbed me in the writing, and the last was an examination of the nature of evil based off of the two Canadian serial killers Paul Bernardo and Carla Homolka, where she was given a lighter sentence because she said he made her do the terrible crimes. Can you be made to commit horrors that go against your fundamental core, and who is more evil–the person committing the crime or the one making that person do it?

And this gets down to what is the scariest thing: to many it is man/woman as monster, the feral side, the side the loses control; like Dracula, like werewolves, like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. You could say my fascination with the weird is my fascination with people and that no matter how normal all of us look there is something that makes us individual, and sometimes it is disturbing. Thankfully though, most of us are just harmless eccentrics.

[image error]Colleen Anderson is a Canadian author with over two hundreds works published including fiction and poetry. She has two fiction collections, Embers Amongst the Fallen, and A Body of Work which was published by Black Shuck Books, UK in 2018. She has been longlisted for a Stoker Award and shortlisted for the Aurora and Gaylactic Spectrum Awards, as well as having placed in several poetry contests. A recipient of a Canada Council Grant, Colleen has served on Stoker and British Fantasy Award juries, copyedited for publishers, and edited three anthologies (Alice Unbound: Beyond Wonderland, Exile Publishing 2018).

Look for some of her work in Canadian Dreadful, Tesseracts 22, Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, The Pulp Horror Book of Phobias and By the Light of Camelot. A book launch for A Body of Work will take place in Vancouver of Feb. 23, at 3pm at The Heatley. Come by and say hi and hear Colleen read. Read a review of the collection here.