Simon Sylvester's Blog, page 17

May 9, 2014

Thievery

I’m honoured and delighted to have contributed a post to Kirsty Logan‘s long-running series of story inspirations, Thievery. It’s entirely possible to drown yourself in the wealth of stories Kirsty has curated, and I thoroughly recommend you do.

For my post, I confessed about a novel I abandoned at 50,000 words, because I no longer knew what it was about. One day, it will be reborn as The Year Of The Whale.

Here’s the story so far: Northern Lights / The Year Of The Whale.

May 8, 2014

Keaton Henson – To Your Health

Lindzee Poi – Amelymeloptical illusion

May 3, 2014

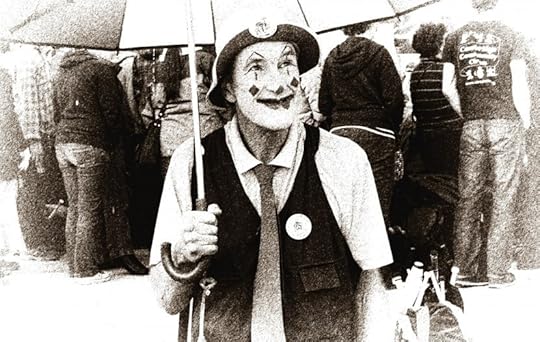

Playing the clown

Last month, at Dreamfired, I saw storyteller Fred Versonnen perform the amazing Elephant Story. The next morning, I attended his clowning workshop in Arnside. This had almost nothing to do with the stereotypical idea of clowning – no silly noses, no silly shoes – and was essentially a 101 on delivery, performance and body language.

Fred warned us at the start of the session that it might take us to some uncomfortable places. I didn’t believe him, but he was right. It’s taken me this entire month to process some of the things that happened in that class. I’m not sure I’ll ever totally get to grips with it, but at the same time, I no longer think I need to. I just wanted to record a few thoughts on what clowning means to me.

I’m not going to talk about the specific activities Fred led us through. They were plentiful, varied, invigorating, intense and brilliantly useful, but they will mean different things to each person who attended, and I don’t feel the need to dissect the actual workshop. I want to talk about what I learned.

I learned that I’m frightened of embarrassment. Most of us are, probably. During the workshop, we performed tasks specifically designed to undermine dignity and strip away the topmost layers of self-respect. I found myself trying to rationalise the embarrassment by imposing a narrative upon it, but every time, Fred forced me to confront it.

‘For a clown, embarrassment is a gift,’ he said.

In this way, I learned that clowns are truly fearless.

I also learned to wait.

In a world consumed with noise and signals, the clown is silent. She waits, absorbing everything, and then she waits some more, until the wait itself becomes excruciating – until the pause itself becomes the embarrassment – and then she responds. In that pause, the clown is naked. Every part of her is laid open for the world to see. The clown waits long enough for the audience to connect, to project their own feelings onto the situation, to drown in empathy, to cringe in anticipation. Every part of them is laid wide open. This is the tragedy of the clown, and the triumph. It has nothing to do with face paint or comedy trousers. Laurel and Hardy are clowns, and Pennywise is not.

I couldn’t live that way, but I’m trying to bring some of it into in my own readings. At the Flashtag story slam, I made myself pause, and wait, then wait some more. I took a stupid hat onstage for my final story, and I forced myself to wear it. I tried to share anticipation of what was coming next with the audience. It was, without a doubt, the happiest I’ve ever been with my performance – the best I’ve ever read my stories. For everything I learned, I’m not sure I’ll ever know how to apply it properly. But I think I understand, now, that not knowing is itself part of clowning. It is Zen – pure action, without thought. I think too much.

At the start of this post, I said that the workshop had nothing to do with silly noses. That isn’t entirely true. At the very start of the session, as people were still arriving, we gathered in the kitchen to wait. Fred began to ransack the drawers, looking for props to use in the workshop. He found an orange ping pong ball. In a single, fluid motion, he spun to face me, bringing the ball to his nose, and he grinned. Just as quickly, he replaced the ball and closed the drawer. But in that second, or half a second, he’d become a clown. His face changed, his body changed - with the sheer, magnificent, wondrous joy of finding a ping pong ball in a kitchen drawer.

I don’t think I’ll ever be able to articulate what happened in that workshop. I don’t need to articulate it, of course, but I want to; and that is why I will never be a true clown. A clown wouldn’t need to analyse it, because they wouldn’t be scared of it. A clown would simply shrug, smile, and turn to embrace the vastness of this mad, sad, glorious thing that we call life.

Stop motion

This is a stunning portrait of life and love and grief, and two of the best minutes you’ll spend today:

The Sprint Mill Sessions

I love this: my friend Dom has been filming the grassroots Cumbrian folk scene. Last summer he gathered dozens of people for a campfire session at Sprint Mill, and this was the result – young musicians, sharing their songs by firelight. The sessions so far can be found right here, but I’ll leave you with Paddy Rogan and The Way You Used To Do…

May 2, 2014

Islands

Islands are everything. Each of us lives on an island, and moves between them constantly. Your island might be called London, or Northumberland, or Withington. Or it might called the office, the supermarket, the bus. For a little while, your island might be as big as a cinema screen, and the population is the audience around you. Sometimes, it’s an island of three – my wife, and my daughter and me, drinking tea by the stove. Sometimes it’s an island of one, contained within the covers of a book. You know the shores of your island entirely, and you look beyond them often. All of life is an archipelago.

April 27, 2014

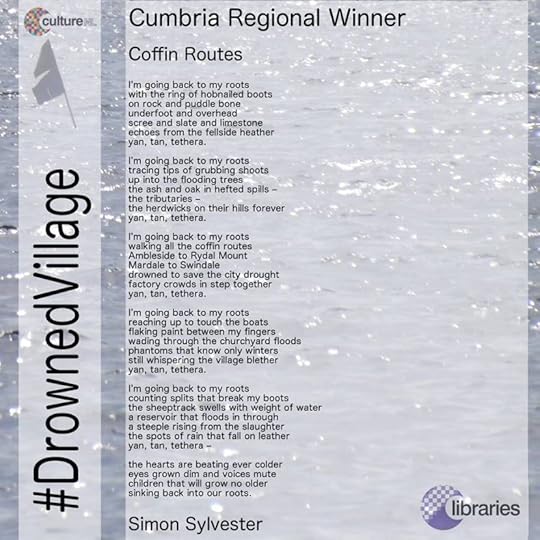

Coffin Routes

A couple of months ago, I posted about the Drowned Villages Poetry Competition. There are drowned villages in Cumbria, Gwynned and Lanarkshire; the competition was open to poets within those library regions, working with that theme. The top prize was having your poem soundtracked by Mogwai. I’m very guarded about my poetry, but Mogwai are one of my favourite ever bands and creators of my all-time favourite album, and so I entered the contest.

Rounding up what’s been an astonishing month for me, I’m both delighted and devastated to reveal that I won the regional contest for Cumbria. I’m absolutely elated that the judges enjoyed my work. I’m still brewing, awestruck, on the momentous thought that Liz Lochhead, Ian McMillan and Nicky Wire have read my poem. But I’m also utterly gutted that having come so close, top prize went to the contestant from North Lanarkshire.

I feel bad even writing that. The first place piece, Never Come Home, is a really striking poem, and I’m sincerely happy for winning writer Catherine Baird. I didn’t expect to feature in the competition at all, so taking a place as runner-up is excruciatingly bittersweet. Having Mogwai do something with my work would have been astonishing - I can’t even frame the shape of it in my mind. I can’t articulate the joy I would have felt. Coming so close has turned me upside-down. I’m genuinely thrilled for Catherine Baird, and delighted with my own poem doing so well, but this one hurts. So near, and yet so far.

I know this sounds churlish. I don’t mean it to. But I discovered Come On Die Young in 1999, and Mogwai have soundtracked the last fifteen years of my life. Without exaggeration, Mogwai’s music has accompanied at least half of my entire writing output. I feel ecstatic to have come so close, and I feel heartbroken to have come so close.

For Facebook users, here’s the winning poem by Catherine Baird. My heartfelt congratulations to Catherine, and I can’t wait to hear the finished song. Like all of Mogwai’s work, it will be extraordinary.

When I was writing the poem, I played Hungry Face from Les Revenants on repeat in the background, hour after hour. I’m listening to Come On Die Young as I write this blog post. May Nothing But Happiness Come Through Your Door is playing. It’s the pivotal point in the album. Next comes the calm before the storm of Oh! How The Dogs Stack Up, and then the astonishing, burning, towering trio of Ex-Cowboy, Chocky and Christmas Steps. I will never stop listening to this album – or the others – the otherworldly Rock Action, the ferocious Happy Songs For Happy People, the dreamworld EP+6, the snarling Young Team, the smouldering Les Revenants, the muscular Hardcore Will Never Die, the reflective Hawk Is Howling, the utter majesty of Government Commissions, the blistering uppercut of Rave Tapes.

I will never stop listening to Mogwai, and I will never, ever stop what wondering what if…

What if.

Here’s my poem.

April 23, 2014

Slamming

After a wild and wonderful night in Manchester, I’m bowled over to report that I somehow managed to win the Flashtag Short Short Story Slam. It’s still sinking in, but I’m delighted.

It was something of a journey - we left Dora with her grandparents, and drove down from Cumbria in the afternoon. Mon and I met friends Steve and Clare in the Northern Quarter, ate in the revelation that is V Revolution, then headed across the road to Gullivers to scope the venue: a brilliant space of worn floorboards and ornate plaster ceilings. The stage was bathed in blue and red light, creating corners from which the writers would prowl to read their stories. For the first round, competitors were paired off at random, with names plucked from a bowl and a coin toss to decide who read first. Once each writer had performed their story, the audience voted blue or red to decide a victor, and that writer continued to the next round.

It started ferociously, with the amazing Joy France reading an intimidatingly strong story about cleanliness (and willies). Her opponent was good, but that story would have annihilated all comers. I was very, very glad I hadn’t been drawn against her. She was duly voted through, and set the bar for the rest of the night. The stories were consistently excellent. Hand on heart, there wasn’t a bum note. Mark Mace Smith and Mark Powell, Joe Daly, Abi Hynes, Sarah Stuart, Geraint Thomas, Trisha Starbrook, Thomas Jennings and Ailish Breen all read absolute belters.

My name was drawn in the fourth bout. I read a piece called What I’ll Do To Be In Love With You, about a boy who turns into a harmonica. I was anxious, as always, but I’d been practicing, and I made myself take the time to enjoy it. My opponent was Thomas Jennings, who read a brilliant piece about the end of the world as experienced through last orders in a MacDonalds. It was a funny and affecting story, and I would have been happy to lose to it; but I scraped through into round two, where I was paired off with Mark Mace Smith. Mark is a vivacious slam poet who often performs under the name Citizen Mace – check out his stuff here – and he made for another tough competitor. I was up first, with a story called Charlie Loved The Circus. This is a 200-word nasty about why you shouldn’t be mean to clowns. Mark’s piece was a sweet wee story about a man falling – literally – for a girl. Another close vote, but I made it to the third round.

In the final, I read against Mark Powell and Joe Daly. Both are stalwarts of the Manchester literary scene – Mark runs Tales Of Whatever, and Joe is one half of Bad Language – and their stories were excellent. I was last to read, and went with a story called The Jubilee Best Bake Competition. I always planned to read this with an accent, but bottled it at Verbalise. So I bought a frumpy hat onstage. It’s made of green wicker, has a broad brim and is covered with flowers. Once I’d donned the hat, I couldn’t back down from the accent; and so I launched into my idea of what happens when the village baking competition takes a turn for the worse. The audience (joined, at this late point, by three exceedingly stocious men who thought they’d come to a boxing match) kindly gave me some laughs, and that helped me relax into the story. The hat helped, too.

The vote was tight again, but I sneaked it. I’m still thrilled, delighted and surprised – as well as humbled and happy to have shared my stories with such an amazing crowd. We stayed for a couple of hours after the slam, happily chatting away with the Flashtaggers, audience and contestants. It made me wish, once again, that I’d made more of the astoundingly vibrant Manchester literary scene when I actually lived there; then again, I’d barely started writing when we lived in Withington.

It was after 11 when we left Manchester, and we drove a deserted motorway in the dark. The journey gave me time to think. I’m over the moon to have won, but there are two things that burn brighter. Firstly, I won’t forget the sense of community I experienced at the slam; it’s a real thrill to share my love of stories with friends and strangers, and events like the slam are a howl of affirmation that stories are alive and people are hungry to share them.

Secondly, and quite honestly, I would have been proud to have been knocked out at any point, from round one onwards. This is because, for the first time, I read my stories the way I want them read. I used to gabble or murmur my way through a reading. A year or so ago, I set out to be better. I haven’t shaken the nerves, but I’m learning to manage them, and I’m coming to trust my stories. I’m not a confident person, but running a gauntlet of open mics has given me some confidence in my work.

Back at home in Cumbria, I tiptoed in to see my daughter. She snuffled in her sleep, and buried herself in the blanket. All journeys, no matter how big, are measured in stages and steps. For all the things I would change about myself – to write more often, to be more focused, to perform better - I wouldn’t change a step of the path I’ve taken to where I stand now.

Here’s a picture of me with a cheesy grin and my cheque for £1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. I’ll be cashing this tomorrow, Flashtag – if there’s any trouble at the Post Office, I’ll be back with my bat.

April 18, 2014

A sealskin coat

The Visitors is a little bit about selkies. Selkies are seals, and they are also people. They have a fur coat that allows them to take the form of a seal. When they step out of the coat, they become human. Selkies can be men or women, but they are always extraordinarily beautiful.

There are a multitude of selkie stories, but the most common starts with a selkie woman removing her coat and dancing on the shore. A young man – usually a fisherman or crofter – spies her dancing, and steals the coat. With her fur held hostage, the selkie has no choice but to marry the man. They live together for a while, but then the selkie finds her skin and escapes back into the sea. The man is left to nurse a broken heart. Often, the couple have children. In some stories, it is a child that finds the coat, and returns it to the mother. Sometimes the selkie takes her children back into the ocean, and sometimes they are left behind. In that version of the story, the mother and children meet in the surf to play.

In the other typical selkie story, an island woman cries seven tears into the sea to attract a selkie mate. Selkie men give children to barren women.

I love the idea of selkies, but I struggle with some aspects of these traditional stories. They crush female independence. In the first, the selkie is kidnapped and loses years of her life to captivity. The man takes what he wants, and is punished only by the accident of her escape. In the second story, the male selkie is a god, and the woman summons him on bended knee. Either human men dominate supernatural women, or supernatural men dominate human women. Both men and women mean more to me than that. When I started writing The Visitors, I wanted something different from selkie stories. I wanted equality. That’s been my guiding light for the novel, from start to finish. John and Izzy share traditional tales, but Ailsa and Flora question the validity of that tradition, and take a closer look at what it means to be a selkie.

I love the idea of selkies, but I struggle with some aspects of these traditional stories. They crush female independence. In the first, the selkie is kidnapped and loses years of her life to captivity. The man takes what he wants, and is punished only by the accident of her escape. In the second story, the male selkie is a god, and the woman summons him on bended knee. Either human men dominate supernatural women, or supernatural men dominate human women. Both men and women mean more to me than that. When I started writing The Visitors, I wanted something different from selkie stories. I wanted equality. That’s been my guiding light for the novel, from start to finish. John and Izzy share traditional tales, but Ailsa and Flora question the validity of that tradition, and take a closer look at what it means to be a selkie.

Selkies are special. I watched the seals hunting in the bay at Grogport, and saw them bask and splash in Portnahaven harbour. There is life and knowledge in their eyes. When you look at them, they look back. On Kintyre, we walked the coast around Skipness on a grey, steely day, and we were followed by a seal. For half a mile or more, as we skirted the coast, the seal stayed twenty or thirty yards away from us. It seemed to move without locomotion, so that dark snub head simply kept pace with us, looking towards the shore. We sat on old stones to eat our lunch, and the seal bobbed and ducked at one end of the headland. It didn’t move away until we struck back inland, and then it vanished in a wink. I looked back to seek it out, but the seal had gone.

I asked my friends about seals and selkies, and they swamped me with stories. Chris gave his first pocket money to Save The Seals. Tom talked to the seals in a sealife centre, and the seals talked back. Dan’s friend confused swallows for seals in a dream, so he drew her a picture of a swallow with a seal’s head. Kirstin’s father whistled to the seals in Shetland, and they popped to the surface to see what all the fuss was about. Jon was kissed by a sealion. Sakina can’t shake the tale of the seal maiden. Ross works in Copenhagen, and daydreams that commuters with sealskin coats are modern-day selkies. Amy holidayed on Mull when she was seven, and spent the summer playing with a selkie called Della.

Why do we give seals such humanity? They are manifestly foreign to us, but the connection is overwhelming.

When I was 25 or 26, I spent a year working and backpacking in Australia. I remember snorkelling on Ningaloo Reef, diving as far down as I could go. I looked up exactly as the sun dropped behind a cloud. The water turned suddenly cold and pressed against me, and I felt very afraid, scared of the deep and the dark and the cold and the blue. When I think of selkies, they are underwater, floating with perfect neutral buoyancy, and shafts of sunlight sway woozy on the surface above. The darkness drops away behind them, and the selkie exists in two places: as a seal, utterly unafraid, and as a human, drawn against the current, compelled to the surface. Selkies live in thresholds. The selkie woman, when she escapes, returns to embrace her children in the surf. The shoreline, changing always with the tide, is where seals and people meet as selkies. It is a nowhere place, and yet it is all they have.

A hunter doesn’t know his wife is a selkie. While hunting, he sees her as a seal, and harpoons her. She becomes human, and dies in his arms.

A hunter doesn’t know his wife is a selkie. While hunting, he sees her as a seal, and harpoons her. She becomes human, and dies in his arms.

The crofter is left heartbroken on the shore, and his selkie wife returns by stealth to see her children.

This selkie is allowed only one night of the year to be human.

Two lovers share a single skin, so that they can never be together in the same form; always one as a seal, and one as a human.

Selkies are born from the souls of drowned sailors.

Selkies are cousins to the muc-sheilche, the kelpie, the nokken, the finfolk. Those creatures are killers and enemies to men. So what makes the seal a victim? A romance? A tragedy?

When we visited Islay, we drove out to Portnhaven. We clambered across the rocks to the weedy edge of the harbour, and we watched the seals. Half a stone’s throw across the water, they gathered to sunbathe by the dozen. They winked as though the Atlantic was a hot tub. They flickered in the water, phantoms bound in straps of kelp. They came so close that I found myself laughing aloud – laughing in wonder, joy and disbelief.

When I started writing The Visitors, I wanted to explore that connection with the seals, that projection of knowledge, and emotion, and empathy. I don’t know if I succeeded, but I’ve fallen more in love with seals and selkies.

My wife found this picture of a seal. It was taken in California, rather than Coll, but it’s the way I see a selkie. Curious and cautious, incredibly close, and impossibly distant.

Simon Sylvester's Blog

- Simon Sylvester's profile

- 39 followers