Kathryn Mockler's Blog, page 23

October 14, 2024

2024 GG Award for Poetry Finalists

This year I had the great honour of being on the peer selection committee for the Governor Genera’s Award for Poetry with Heather Nolan and Tolu Oloruntoba. I feel very fortunately to have been in conversation with these two poets that I admire.

The selection process was difficult as there are so many wonderful books that came out this year in 2023-24.

These were the finalists that we chose.

Their books are beautiful and important, and I urge you to read them.

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedThe Work (Gaspereau Press) by Bren SimmersPrecedented Parroting (Palimpsest Press) by Barbara TranThe All + Flesh (House of Anansi Press) by Brandi BirdSonnet from a Cell (Brick Books) by Bradley PetersScientific Marvel (House of Anansi Press) by Chimwemwe Undi

Support Send My Love to Anyone

Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

Making Sense of the World Through Short Fiction at Victoria Festival of Authors | October 20, 2024

Send My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this project, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I’m thrilled to be moderating Making Sense of the World Through Short Fiction at the Victoria Festival of Authors with Carleigh Baker, Shashi Bhat, and Debbie Bateman!

TicketsTickets are on a sliding scale, and this event will be both in person and live-streamed. Reserve your spot now.

Date and timeStarts on Sunday, October 20 · 7:30pm PDT

LocationLangham Court Theatre, 805 Langham Court Victoria, BC V8V 4J3

About This EventJoin us for a conversation with Carleigh Baker, Debbie Bateman, and Shashi Bhat who will read from their exciting new story collections and discuss how they use the short form to grapple with some of the most pressing issues of our times such as bodily autonomy, consent, white supremacy, the climate crisis, aging, grief, disability, and loneliness.

Whether it’s Baker’s harrowing and satirical disaster tales in Last Woman, Bateman’s raw portraits of middle-age women and their bodies in Your Body Was Made for This, or Bhat’s unflinching take on dating and relationships in Death by a Thousand Cuts, these urgent and timely stories offer visceral, biting, and often humorous depictions of contemporary life.

Moderated by Kathryn Mockler

Carleigh Baker is an nêhiyaw âpihtawikosisân/Icelandic writer who lives as a guest on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh, and səlilwətaɬ peoples. Her debut story collection, Bad Endings, won the City of Vancouver Book Award, and was a finalist for a BC Book Prize, an Emerging Indigenous Voices Award, and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Award.

Shashi Bhat has written three books of fiction, most recently the story collection Death by a Thousand Cuts. Her fiction received the Writers’ Trust/McClelland & Stewart Journey Prize and was a finalist for the Governor General's Award for fiction, the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award, the National Magazine Award for fiction, and the RBC Bronwen Wallace Award, and was longlisted for the Giller Prize. She is the editor of EVENT and teaches creative writing at Douglas College.

Debbie Bateman graduated from The Writer’s Studio at SFU. Her short stories have appeared in literary magazines and an anthology. Your Body Was Made for This is her first book. A quiet rebel and a Buddhist, Debbie lives in Quw’utsun (Cowichan) on Vancouver Island with her husband and soulmate.

Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

Send My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

October 12, 2024

Where Do I Start? Writing Prompts

Where Do I Start? is a section of Send My Love to Anyone that includes prompts and resources for any genre of creative writing by Kathryn Mockler and sometimes guest authors.

I named this section Where Do I Start? because this is the question I ask myself before I begin any writing project.

No matter how long I’ve been writing, at the outset of any creative undertaking, I always feel lost, confused, excited, and terrified—just like I did when I first began writing in my early 20s. And I always have a moment of wonder in the process when I ask—where do I even start?

Over the years, I’ve learned this is part of my writing process. Writing for me is about feeling lost and then finding my way through an idea.

I hope these writing prompts and resources help you along your journey no matter where you’re at.

About Kathryn MocklerKathryn Mockler has taught creative writing for 23 years and is currently an Associate Professor at the University of Victoria where she teaches short fiction and screenwriting.

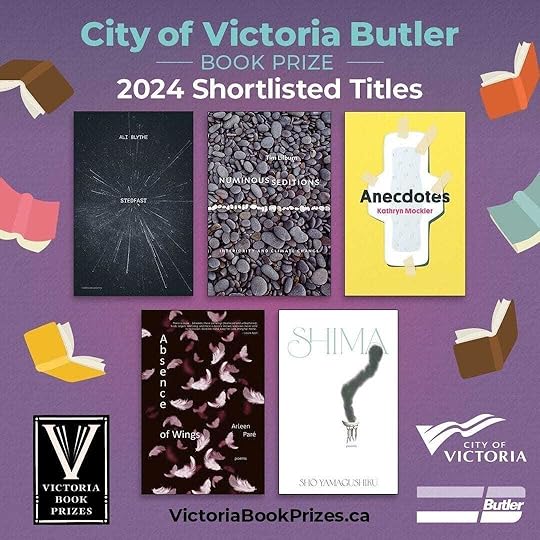

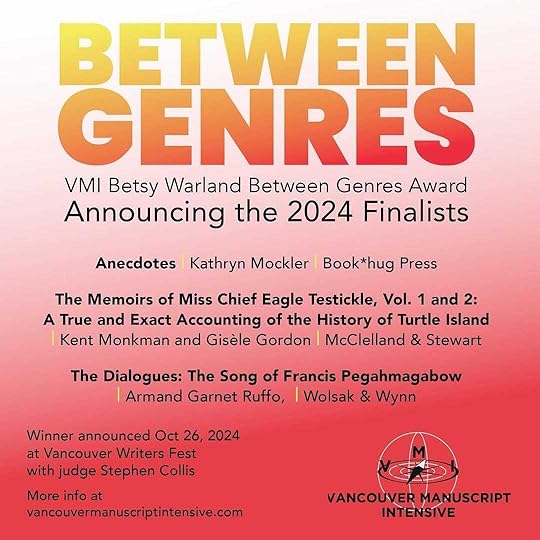

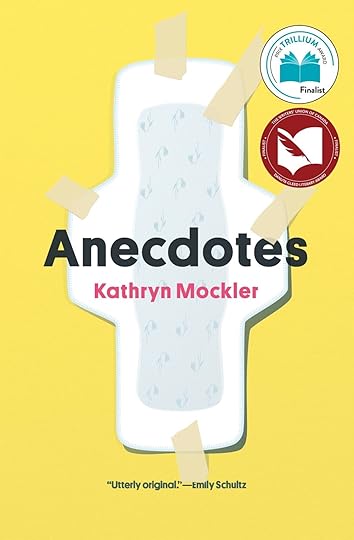

She is the author five books of poetry, several short films, and the story collection Anecdotes (Book*hug Press, 2023), which won the 2024 Victoria Butler Book Prize and was a finalist for the 2024 Trillium Book Award, 2023 Danuta Gleed Literary Award, 2024 Fred Kerner Award, and 2024 VMI Besty Warland Between Genres Award.

She is a graduate of UBC’s MFA program, an alum of the CFC Screenwriter’s Lab, and a TIFF Talent Lab participant. She won the San Francisco Film Society Screenwriting Fellowship and was a Nicholl semifinalist and a Zoetrope and BlueCat Quarterfinalist. Her films and experimental videos have screened at such festivals as TIFF, EMFA, Palm Springs Film Festival and most recently at the Arizona Underground Film Festival and REELPoetry/HoustonTX.

She published The Rusty Toque from 2011-2017, was the Joyland Canada Editor from 2013-2020, and published Watch Your Head from 2019-2023.

She co-edited the print anthology Watch Your Head: Writers and Artists Respond to the Climate Crisis (Coach House Books, 2020) and she runs Send My Love to Anyone, a literary newsletter which was a featured Substack in 2023.

Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

October 9, 2024

Gatherings | Issue 41

I have a busy month ahead. Looking forward to things slowing down in November.

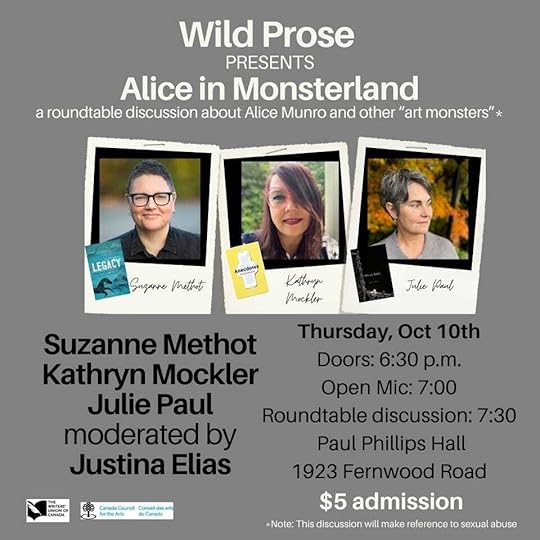

I’ll be participating in this event in Victoria on October 10, 2024.

Wild Prose presents: Alice in Monsterland. A roundtable discussion about Alice Munro and other “art monsters” with Suzanne Méthot, Kathryn Mockler, and Julie Paul; moderated by Justina Elias

I'm grateful to be included in this panel.

It's going to be a difficult discussion but one well worth having I believe.

I appreciate the care and nuance that the organizers have taken with this event.

Event Details: Thursday, October 10th Doors: 6:30 p.m. Open mic: 7:00 p.m. Readings: 7:30 p.m. at Paul Phillips Hall, 1923 Fernwood Rd. Victoria $5 admission (CASH)

I'm honoured to have Anecdotes shortlisted for the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize with these writers and authors I admire greatly!This is especially meaningful since I am relatively new to the city and in awe of its welcoming literary community. Congratulations to all!

The winners will be announced during a gala event on Wednesday, October 16, 2024, at 7:30 p.m. at the Union Club of British Columbia. Tickets are available on eventbrite.

So grateful to Deborah Vail for interviewing me and reviewing Anecdotes (Book*hug Press) in

PRISM international.

So grateful to Deborah Vail for interviewing me and reviewing Anecdotes (Book*hug Press) in

PRISM international.

I love her questions, and at the end, I get the opportunity to share some books by writers whose work I admire (Saeed Teebi, Shashi Bhat, and Jacob Wren).

I’m thrilled to moderate this event at the Victoria Festival of Authors

Making Sense of the World Through Short Fiction with Carleigh Baker, Shashi Bhat, and Debbie Bateman

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedJoin us for a conversation with Carleigh Baker, Debbie Bateman, and Shashi Bhat who will read from their exciting new story collections and discuss how they use the short form to grapple with some of the most pressing issues of our times such as bodily autonomy, consent, white supremacy, the climate crisis, aging, grief, disability, and loneliness.Whether it’s Baker’s harrowing and satirical disaster tales in Last Woman, Bateman’s raw portraits of middle-age women and their bodies in Your Body Was Made for This, or Bhat’s unflinching take on dating and relationships in Death by a Thousand Cuts, these urgent and timely stories offer visceral, biting, and often humorous depictions of contemporary life.Moderated by Kathryn MocklerTickets through eventbrite

I’m beyond honoured to be a finalist for the VMI Betsy Warland Between Genres’s Award with Kent Monkman and Gisèle Gordon for their book The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Vol. 1 and 2: A True and Exact Accounting of the History of Turtle Island, McClelland & Stewart, and Armand Garnet Ruffo for The Dialogues: The Song of Francis Pegahmagabow, Wolsak & Wynn!

Thanks to Stephen Collis who judged the awards! Congrats to all!

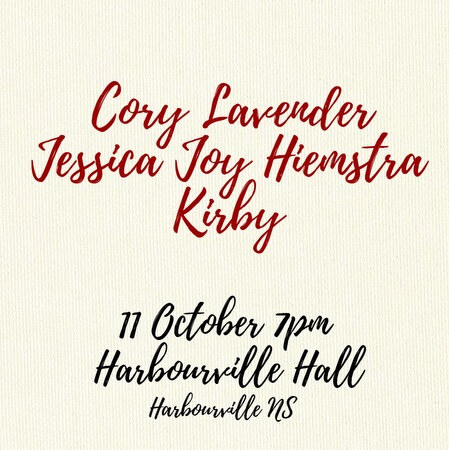

Kirby News

Kirby NewsKirby reads with Cory Lavender, Jessica Joy Hiemstra in Harbourville, NS at 7pm at Harbourville Hall

Kirby and Sue Goyette at The Trident in Halifax, N.S. at 7pm.

Send My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this project, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

GatheringsRoom is hiring a new Managing Editor! - Deadline October 11, 2024

Join Workshops for Gaza for our first poetry reading featuring a small fraction of the many U.S.-based poets in solidarity with the people of Gaza: Fady Joudah, Solmaz Sharif, Wendy Trevino, Juliana Spahr and Joshua Clover. All proceeds will go to Hamza, a Palestinian writer and student of the late and beloved poet Refaat Alareer. Hamza is currently raising funds to help his family of 40 survive the ongoing genocide.

To register for “A Poetry Reading for Gaza,” donate to Hamza (suggested donation $25 USD, please donate more if you can!) then fill out the registration form.

The first time I travelled outside of Gaza, I was twenty-seven years old. Growing up, I had always thought of “travel” as riding a taxi, bus, or bike within the borders of the Gaza Strip. My family lived not far from Railway Street, but there were no trains there. I had heard stories about the Gaza International Airport, but Israel had bombed it when I was eight. I remember asking my childhood friend Izzat, a soccer fan, about the places he wanted to visit one day. “Barcelona,” he told me. “I want to play alongside Messi, Xavi, and Iniesta.” In 2014, a few days after Izzat graduated from college, he was killed in an Israeli air strike. Our freedom of movement was just another victim of the occupation.

Read The Pain of Travelling While Palestinian by Mosab Abu Toha in The New Yorker

Author Jhumpa Lahiri declines NYC’s Noguchi Museum award after keffiyeh ban No More Abysses, No More WallsWhy I Withdrew My Book From the GillersWhen I first became aware that authors were pulling their books from consideration for the Giller this year—in protest of the principal sponsor Scotiabank and their holdings in Elbit Sytems, an Israeli weapons company—I knew immediately I would remove my latest book…Read more8 days ago · 4 likes · 1 comment · Aaron Kreuter

No More Abysses, No More WallsWhy I Withdrew My Book From the GillersWhen I first became aware that authors were pulling their books from consideration for the Giller this year—in protest of the principal sponsor Scotiabank and their holdings in Elbit Sytems, an Israeli weapons company—I knew immediately I would remove my latest book…Read more8 days ago · 4 likes · 1 comment · Aaron Kreuter

Read An open letter from Michael Ondaatje, Madeleine Thien and six other Giller winners: It’s time for the prize’s funders to divest from companies whose products are enabling the mass killing in Gaza in The Toronto Star

I didn’t know and nobody told me and what

could I do or say, anyway?

Read “Apologies to All the People in Lebanon” by June Jordan in Poetry

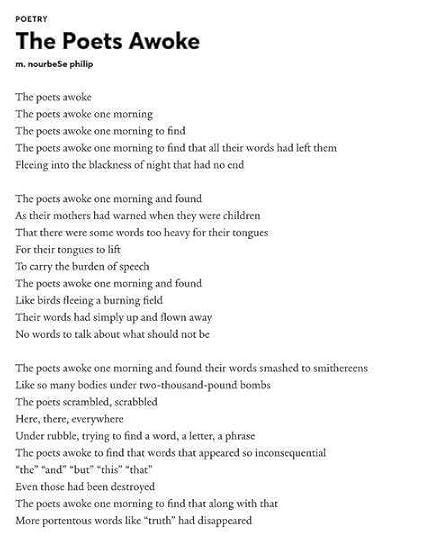

Read m. nourbSe philip in The Yale Review yalereview A post shared by @yalereview

A post shared by @yalereviewIn 1953, Roald Dahl published “The Great Automatic Grammatizator,” a short story about an electrical engineer who secretly desires to be a writer. One day, after completing construction of the world’s fastest calculating machine, the engineer realizes that “English grammar is governed by rules that are almost mathematical in their strictness.” He constructs a fiction-writing machine that can produce a five-thousand-word short story in thirty seconds; a novel takes fifteen minutes and requires the operator to manipulate handles and foot pedals, as if he were driving a car or playing an organ, to regulate the levels of humor and pathos. The resulting novels are so popular that, within a year, half the fiction published in English is a product of the engineer’s invention.

Read Why AI Isn’t Going to Make Art by Ted Chiang in The New Yorker

Each of Sally Rooney’s novels writes back to a novel that she admires: Conversations with Friends to Jane Austen’s Emma; Normal People to George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda; Beautiful World, Where Are You to Henry James’s The Golden Bowl; and Intermezzo to James Joyce’s Ulysses. But while Rooney is delightfully conversant in the history of the novel, it is not, she says, her first thought when she starts to write. Her characters simply walk into her mind and stay there until she has puzzled out the precise nature of their relationships to one another. In Intermezzo, as in the novels that preceded it, her characters—Peter and Ivan Koubek, and the women they love—are often self-deceiving, misguided, and dishonest. No one’s intentions are pure. No one’s actions are consistent. Yet amid this tangle of secrets and lies there is, every so often, a glimmer of mutual understanding—a minor triumph in a world designed to erode all human exchanges and emotions. It is the burden and the pleasure of the novel, from Austen to Rooney, that it can animate these triumphs and the unbeautiful world from which they arise, so long as we keep turning the pages.

Read Loving the Limitations of the Novel: A Conversation between Sally Rooney and Merve Emre in the Paris Review

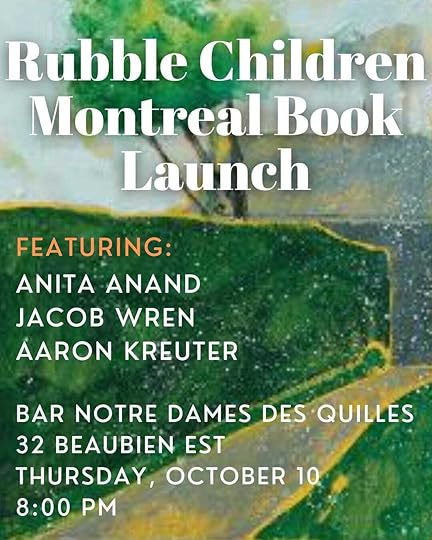

Thurs Oct 10 at 8pm: Aaron Kreuter's Montreal Launch for Rubble Children with Jacob Wren and Anita Anand at Bar NDQ

Chelene Knight on self-discovery for writing strategies that stick!

Chelene Knight on self-discovery for writing strategies that stick!I love all things breaking the rules! Check out the latest from

Looking back, Smith sometimes marvels that Dickinson was made at all. “It centers an unapologetic, queer female lead,” she said. “It’s about a poet and features her poetry in every episode—hard-to-understand poetry. It has a high barrier of entry.” But that was the time. Apple, like other streamers, was looking to make a splash. “I mean, they made a show out of I Love Dick,” Smith said, referring to the small-press cult classic by Chris Kraus, adapted into a 2016 series for Amazon Prime Video. “That doesn’t happen because people are using profit as their bottom line.”

Read The Life and Death of Hollywood; Film and television writers face an existential threat by Daniel Bessner in Harpers

Love these essay prompts by !

Werk-In-ProgressHere Are Some Ideas For Essays You Could WriteHey y’all — I’ve been quiet for a while, too quiet actually, but I had a good reason. I’ve gotten started on a new book and I moved from Columbus to Cambridge, MA to be the artist-in-residence at Harvard Medical School. Long story, maybe I’ll explain later. Probably won’t, I’m hella busy…Read more18 days ago · 374 likes · 33 comments · Saeed Jones

Werk-In-ProgressHere Are Some Ideas For Essays You Could WriteHey y’all — I’ve been quiet for a while, too quiet actually, but I had a good reason. I’ve gotten started on a new book and I moved from Columbus to Cambridge, MA to be the artist-in-residence at Harvard Medical School. Long story, maybe I’ll explain later. Probably won’t, I’m hella busy…Read more18 days ago · 374 likes · 33 comments · Saeed JonesWe should rid our writing of the domestication of atrocity, rid our writing of the tense that insists on the innocence of its perpetrators, the exonerative tense of phrases like “lives were lost” and “a stray bullet found its way into the van” and “children died.” We should rid our writing of this dreadful innocence. We should refuse the logic that produces a phrase like “human animals” and a “four-year-old young lady.”

Read The Shapes of Grief: Witnessing the Unbearable by Christina Sharpe in The Yale Review

does the Questionnaire!

Oldster MagazineThis is 52: Author and #1000wordsofsummer Leader Jami Attenberg Responds to The Oldster Magazine QuestionnaireFrom the time I was 10, I’ve been obsessed with what it means to grow older. I’m curious about what it means to others, of all ages, and so I invite them to take “The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire…Read more21 days ago · 142 likes · 22 comments · Sari Botton

Oldster MagazineThis is 52: Author and #1000wordsofsummer Leader Jami Attenberg Responds to The Oldster Magazine QuestionnaireFrom the time I was 10, I’ve been obsessed with what it means to grow older. I’m curious about what it means to others, of all ages, and so I invite them to take “The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire…Read more21 days ago · 142 likes · 22 comments · Sari BottonSMLTA contributor Christine Estima on What Happened Next

SMLTA contributor Deborah Dundas on What Happened Next

From the ArchiveSupport Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

October 2, 2024

Send My Love to Anyone | Issue 40

Hello friends,

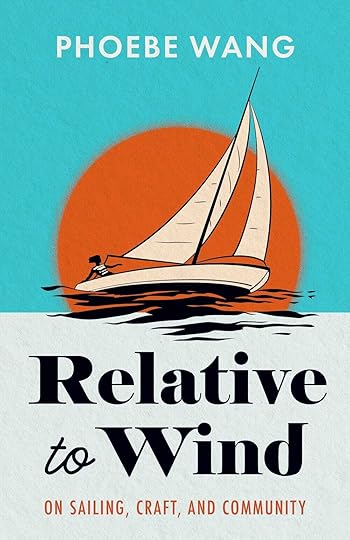

I’m excited to share Issue 40 with you which includes Phoebe Wang’s essay “Becoming Crew” from her new collection Relative to Wind: On Sailing, Craft, and Community; Hollay Ghadery “On Writing While Neurodiverging”; two poems from Myna Wallin’s latest collection, The Suicide Tourist; three poems from Kirby’s latest collection, she, translated into French by poet Jérôme Melançon; “A Young Boy on Whose Father a Tree Has Fallen,” an old story of mine from 2002, and ICYMI Issue 40’s Gatherings.

Thanks to all the Send My Love to Anyone subscribers who make this newsletter possible!

If you enjoy this newsletter, please share, comment, or subscribe!

And let me know if you have your own news to share in the comments!

xo

Kathryn

Send My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this project, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Will I make it will I make it will I?

It’s a few minutes past five on a sharp spring afternoon. I gaze ahead at the dove-grey slice of lake. It’s not far, but there are so many crosswalks and intersections slowing me down. Every time a big red hand goes up, I’m forced to stop running. I suck in big breaths of air, check my phone, and wedge my body ahead of the other pedestrians. People—there are so many people in my way. Office workers power-walking to Union Station, tourists walking three or four abreast, couples arm in arm, Blue Jays fans clogging York Street near the stadium. I jog underneath the Gardiner Expressway and across streetcar tracks toward the waterfront. To anyone watching, I look like another irritable, impatient Torontonian. I feel like I’m fleeing and chasing something at the same time.","size":"lg","isEditorNode":true,"title":"Phoebe Wang | Issue 40","publishedBylines":[],"post_date":"2024-09-28T04:45:49.592Z","cover_image":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f... My Love to Anyone","publication_logo_url":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f...

When my first book came out in 2021—Fuse, a memoir of mixed race identity and mental illness that dove into my long history of eating disorders, addiction, OCD, self-harm, and anxiety—many readers commented on its unusual structure. Unlike many memoirs, it’s not chronological. It's structured thematically. A veritable Jackson Pollock of feeling. Any loose chronological organization owes thanks to my editor, who convinced me that as a memoir, I needed to root the reader in some vague notion of time.

Which was fair enough.","size":"lg","isEditorNode":true,"title":"Hollay Ghadery | Issue 40","publishedBylines":[{"id":21201715,"name":"Kathryn Mockler","bio":"Kathryn Mockler is the author of Anecdotes (Book*hug Press) which was a finalist for the 2024 Trillium Book Award and shortlisted for the 2023 Danuta Gleed Literary Award. She teaches creative writing at the University of Victoria.","photo_url":"https://substack-post-media.s3.amazon... My Love to Anyone","publication_logo_url":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f...

Lithium—my saviour,

mummified me in cotton batting,

weightless.

I leave softer footprints.

The bloodhounds quiet,

curl up at my feet.

I feel blackness

peel off the walls,

and I am grateful.

\t","size":"lg","isEditorNode":true,"title":"Myna Wallin | Issue 40","publishedBylines":[{"id":108762125,"name":"Myna Wallin","bio":"Myna Wallin has published 4 books, including Confessions of a Reluctant Cougar (Tightrope Books, 2010) Anatomy of An Injury (Inanna Publications, 2018), and The Suicide Tourist (Ekstasis Editions, 2024).","photo_url":"https://substack-post-media.s3.amazon... Substack","primaryPublicationId":1504557}],"post_date":"2024-09-15T19:32:52.205Z","cover_image":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f... My Love to Anyone","publication_logo_url":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f...

Then, one morning, I woke up to these beauteous translations by Jérôme to three poems from my new collection, she. It’s the first time (I’m aware of) my work has ever been translated (here, from English to French) and we’re delighted to share them with you. Enjoy.","size":"lg","isEditorNode":true,"title":"3 poems from \"she\"","publishedBylines":[{"id":16955065,"name":"KIRBY","bio":"The pansy. Not the cream puff. poetryisqueer.com ","photo_url":"https://bucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-... First Time","id":149634339,"type":"newsletter","reaction_count":0,"comment_count":0,"publication_name":"Send My Love to Anyone","publication_logo_url":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f...

I wrote this story many years ago, and it was one of the rare writing experiences I’ve had where I felt like I was channelling the story or rather the story was being channeled to me—not quite sure how channeling works, but that’s what it felt like.

Has that ever happened to you? It’s quite and experience, and I’m not sure I’d even believe it if it hadn’t happened to me.","size":"lg","isEditorNode":true,"title":"A Young Boy on Whose Father a Tree Had Fallen","publishedBylines":[{"id":21201715,"name":"Kathryn Mockler","bio":"Kathryn Mockler is the author of Anecdotes (Book*hug Press) which was a finalist for the 2024 Trillium Book Award and shortlisted for the 2023 Danuta Gleed Literary Award. She teaches creative writing at the University of Victoria.","photo_url":"https://substack-post-media.s3.amazon... My Mind","id":149696033,"type":"newsletter","reaction_count":0,"comment_count":0,"publication_name":"Send My Love to Anyone","publication_logo_url":"https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f... the ArchiveSupport Send My Love to Anyone

Support Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

Hollay Ghadery | Issue 40

When my first book came out in 2021—Fuse, a memoir of mixed race identity and mental illness that dove into my long history of eating disorders, addiction, OCD, self-harm, and anxiety—many readers commented on its unusual structure. Unlike many memoirs, it’s not chronological. It's structured thematically. A veritable Jackson Pollock of feeling. Any loose chronological organization owes thanks to my editor, who convinced me that as a memoir, I needed to root the reader in some vague notion of time.

Which was fair enough.

But this grounding impulse didn't come naturally to me. I don’t set out to be purposely abstruse, it's just the narrative drive of the stories I tell originate in the how and why more often than the when and where.

I'm not sure I’m explaining this clearly. I feel myself—the self I speak with in my head—slide out of frame like one of Dali's deflated clocks. Let’s try again.

Once upon a time, I tried to write a novel.

I did write a novel.

The novel I wrote was not the novel I set out to create.

But I need to go further back than this.

After my collection of short fiction, Widow Fantasies, was accepted for publication, my editor said he'd like to see what I could do with a longer form. Understand: if I'd written traditionally-sized short stories instead of stories that ran the gamut between flash and the unseeming length of about three pages and that (unintentionally, in retrospect) challenge many narrative traditions, maybe I wouldn't have internalized my editor’s statement the way I did. At the time, though, when he said he’d liked to see what I could do with a longer form, what I heard was: this is cute, but can you do anything normally?

Which is of course not at all what he actually said. Or meant, I'm sure.

My squirrely interpretation has more to do with the fact that I am aware of the fact that I don't seem able to do things normally. And don’t say “what’s normal” because we all know. There’s a narrative standard. A convention. A tradition. And I know it because I have tried to harness it many times and it eludes me.

When I write, I am aiming to create something fresh, yes, exciting, yes, but I am never trying to confound.

I have these ideas that float about me, and they appear within a range of normal, but when I feed them through my fax-machine brain, what comes out the other side is seldom recognizable as what went in.

About that novel I mentioned.

I meant to write some sort of family saga that examined how women uphold the patriarchy told through the perspective of at least three women.

I ended up with one perspective. And it is the perspective of a sock puppet. The person the sock puppet is attached to says nothing directly the whole book. Not a word. The sock speaks or remembers for this person. Though, of course, the sock is the person, so the human is speaking the entire time.

I toyed with the idea of adding an omnipresent narrator to the mix. A couple of beta readers suggested one might be good to afford the story another perspective, but I recoiled at the very thought. Examining my reaction, I realized that I felt as though people didn't trust the puppet. As though they thought because the puppet was not a reliable narrator of its own experience. I felt strongly that no one should be allowed to delegitimize the puppet's experiences.

During the early drafts of the novel, I'd made a prototype of the puppet and had grown rather attached to its fuzzy and fraying rain-cloud coloured self. Where the puppet ended and I began to blur about the edges. So, when people said the puppet wasn't a reliable narrator, I felt like I was being accused of being unreliable. To my mind, the puppet was the only reliable even-headed character in the whole story.

I began to think about how so many people like myself—and women in particular—who are neurodivergent, historically and even now, are seen as unreliable narrators of our own lives. We aren't trusted to tell our stories: to reliably assess our own lives. We are patted on the head. Appeased. Drugged. Institutionalized. But not believed. At least not fully.

I’m happy to say the sock remains the sole narrator of the novel. I am and will continue to be open to edits that will add clarity and enhance the writing, but I have arrived at a place in my creative life where I refuse to use neurotypical scaffolding (e.g. a longer story or an omnipresent narrator) to make my neurodivergent mind more palatable.

I mean, let's be honest: I wouldn't know how to if I tried.

Hollay Ghadery is a multi-genre writer living in Ontario on Anishinaabe land. Fuse, her memoir of mixed-race identity and mental health, was released by Guernica Editions in 2021 and won the 2023 Canadian Bookclub Award for Nonfiction/Memoir. Her collection of poetry, Rebellion Box was released by Radiant Press in 2023, and her collection of short fiction, Widow Fantasies, is scheduled for release with Gordon Hill Press in fall 2024. Her debut novel, The Unraveling of Ou, is due out with Palimpsest Press in 2026, and her children’s book, Being with the Birds, with Guernica Editions in 2027. Hollay is the host of The Neighbourhood Bookclub on 105.5 FM, as well as a co-host HOWL on CIUT 89.5 FM. She is also a book publicist and the Poet Laureate of Scugog Township. Learn more about Hollay at www.hollayghadery.com. Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

October 1, 2024

A Young Boy on Whose Father a Tree Had Fallen

Photo by Justin Ziadeh on Unsplash

Photo by Justin Ziadeh on UnsplashSend My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this project, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“A Young Boy on Whose Father a Tree Had Fallen” is fictionalized account of a family story about the loss of a beloved pet.

I wrote this story many years ago, and it was one of the rare writing experiences I’ve had where I felt like I was channelling the story or rather the story was being channeled to me—not quite sure how channeling works, but that’s what it felt like.

Has that ever happened to you? It’s quite an experience, and I’m not sure I’d even believe it if it hadn’t happened to me.

It took a year to write this, and whomever was channeling me (perhaps and most likely my grandfather) demanded that I go slow, paragraph by paragraph, revising and rewriting at what felt like a snail’s pace.

I did not feel in control of the process at all, but rather more like a witness to the process. I even surprise myself by saying these words. I have never had a writing experience like this again.

But, hey, universe I’m open to it!

Hope you enjoy!

A Young Boy on Whose Father a Tree Had FallenEverything's different now, even the rain. It's cold and Jim's used to the warmth of summer rain. He's never lived in the city, but he knows the air will taste like metal. He also knows the house he and Vye bought is on a street with houses as close to each other as the length of his body.

The hinges on the barn door are about to give way. He opens it carefully; he doesn't want to have to fix it before Thursday. Jim has come to see Boxer before church. His once warm body lies in the middle of the barn floor. Jim doesn't get too close. He half-expects the dog to jump up as always and lick his face. He wants so badly to say Boxer the cows, to see the tail go and the dog nip at the heels of the Holsteins.

—Is he dead? Vye meets Jim by the drive house. She likes the Pontiac warmed up. Jim smokes a Du Maurier while Vye climbs in the passenger side. —Boxer was such a good dog. It's a shame the Reeves didn't take him.

At church Jim mouths the words to the hymns. He watches the others and takes in a breath when they do, turns the page when they do. Vye's in the choir. She stands at the back, to the right. Jim wonders if she ever watches, if she knows he doesn't sing.

Jim hasn't talked all morning, and he feels that if he opened his mouth, he'd never be able to speak again. He imagines this is the way someone's throat would feel had they done nothing but talk all day. Sometimes he'll go days barely uttering a word. It's not like Vye has to ask what he wants in his coffee or for breakfast. She knows. They carry on like two people moving through the dark in a house they've lived in all their lives. Where they know the rooms better than the sight of their own faces and there's no need to bother with lights.

When the minister says “Our Father” Jim can't help but picture his own father dressed for church in a white shirt with suspenders. Jim was only fourteen years old when the tree fell and broke his father's neck. He was home for the holidays. The first snow had come and gone, and the bare ground had reminded Jim more of an early spring than of Christmas. They were in the woods, just the two of them, sawing a Maple for firewood to sell in town. The money was to be put away to help Jim through school. He had wanted to be a vet.

They cut down the first tree. Jim, heeding instructions from his father, managed the saw like a pro. They watched the next tree fall and tangle itself in another tree. The moment unfolded briefly, precisely with an undeniable fate. This was the way things were going to happen, and no matter how badly anyone wanted to change them, nothing on God's green earth, Jim’s mother would say years after the incident, could change the way that damn tree landed. When the heavy branch got Jim's father under the chin, Jim held his breath. His father was silent, eyes shut as peacefully as if he were sleeping. A bird sound hung above him in the trees. Jim was afraid to move, but he knew he had to. As he crept toward the scene, a twig under Jim's foot broke in two, and as if on cue, Jim's father opened his eyes and barked for Jim to fetch Clive Reeves, the man who owned the farm next to theirs. Jim froze, and it was a moment before he could even get the courage to run. But when his father shouted Clive Reeves for the second time, with what sounded like his last breath, Jim ran. He never looked back. He ran with the force and determination of a sprinter, of someone being chased, of a young boy on whose father a tree had fallen.

Clive Reeves and his son slid a wood board under the limp but conscious man and carried him through the dense woods to the clearing where the horse cart was waiting. The three months that followed are clearer than any other time he can think of. It wasn't the fact that his father was paralyzed, or that he was barely conscious, or the burning fevers, or even the daily visits from friends and neighbours. It was seeing the small, black leather bag peak around the top of the stairs that first night, and a low voice whisper to his mother in the hall, Comfort him as best you can, that made Jim realize, for his father, it was only a matter of time.

After the service, the minister announces that there will be a gathering, a goodbye party in honour of Jim and Vye's move to the city. Everyone claps. Jim looks down, away from the stares and smiling faces. Vye has belonged to this church all her life. She will miss it.

Lorne Johnston, a wealthy farmer who sits two pews back, pats Jim's shoulder in a way that would suggest they were friends. Although Vye doesn't like Jim to hate anyone, Jim has despised Lorne Johnston ever since he set foot in this township. He was born and raised in the city and runs his farm like a factory. It's men like him, Jim has been know to say after a few shots of whiskey, that run the real farmers out of the county with their tail between their legs. Little did Jim know that he would be talking about himself, or maybe he did know and resented the Lorne Johnston's of the world all the more for it.

The choir with the help of Mrs. Owen's Sunday school class has made a papier-mâché piñata in the shape of a hammer. Though they've told everyone they're buying the store, the owner doesn't want to sell for a year or so, and working there, Jim and Vye have decided, would be a good way for Jim to learn the business. —t's not lying, Vye said. —It's just not revealing all the truths at once.

Jim and Vye are blindfolded and both turned around. Vye takes a crack at the hammer and misses. —You have a go now, Jim, Vye says.

Perhaps it's beginner’s luck or the instinct, usually reserved for the blind, of knowing the location of an object without seeing it. Or maybe under the darkness of the blindfold it's Lorne Johnston's face he imagines when he takes hold of the stick. But whatever the force behind him, whatever the luck or unluck depending on the way one chooses to see it, Jim takes once swing at the glorious papier-mâché hammer and brings it down intact.

Jim removes his blindfold and looks at the piñata on the floor. Everyone stands around grim-faced. Jim feels like the spoilt child who has thrown a tantrum at his own birthday party. In the moment before anyone has a chance to speak, Jim sees a young boy, the Keller boy, not much older than five or six standing beside him. He hands the stick to the child who bashes the hammer with all his might, at which point all laughter and gaiety is resumed, leaving Jim officially off the hook.

The goodbye party is in full swing. They've even broken out some of Gillespie Keller's homemade beer for the occasion. Someone's put the phonograph on and everyone is dancing to Guy Lombardo and remembering. Even Jim is dancing despite himself. Vye smells the same as she did twenty-five years ago. She smells of Lily-of-the-Valley talc: her luxury. A small luxury that sits on the back of the toilet in a round pink tub that she has used after her bath all these years. For a brief moment, Jim can't help but feel young.

When the song ends everyone changes partners except Jim who slips over to a corner table and watches. There's something about the dog that he can't get out of his mind. As he was leaving the barn this morning, he swears he saw Boxer's tail twitch. If he mentions it to Vye she will say he is crazy. She will say it's his eyes playing tricks on him or wishful thinking. And she will be right. He knows that as well as he knows anything else.

The day before last, before the vet came to put Boxer down, Vye said Boxer placed his paws on her shoulders and looked into her eyes as if to say save me, save me. When Jim brought the shovel around the back of the house, Boxer followed. What bothered Jim as he dug the hole that would eventually be the dog’s grave was that Boxer probably thought he had done something wrong, that somehow, he were to blame for the events that were about to unfold. The dog's eyes didn't plead with Jim the way they had with Vye. But the guilt ate at him all the same. They couldn't take Boxer to the city. If the cars didn't kill him, the confinement would be something close to suffocation. He couldn't have done that to this dog. And if no one wanted him then a quick, painless death was the next best thing.

For the last three hours Vye’s been keeping an eye on Jim. He's moved from his corner only once since they danced and that was to use the toilet. Jim can't help it if she's social and he's not. Usually he leaves right after church and someone from the choir drives Vye home. He's staying today because it's special—because they're leaving. In some ways it might have been better for Vye, more fun, if he had just gone on home as usual. He knows it would have been better for him. He feels bad that she feels she has to watch him. On the ride home she won't say anything about it, and neither will he.

As they drive down the gravel lane toward the farm, Jim feels a calm and quietness that has never been there before. He stops the car in front of the house to let Vye out. She is annoyed with him for the way he behaved at church. Jim parks in the drive house. He turns the ignition off and sits for a moment holding the steering wheel, for dear life. He shuts his eyes, and all he can think of is the barn and having to carry his dog to the hole that he dug and covered with tarp.

If Jim could change everything, he would. He would stay by his father's side as he lay dying on the cold, damp ground. He would wait for someone to come because the help that did come didn't make a difference in the long run. How he would have loved to hold his father's hand and hear his last words. If Jim could change everything, he would keep the farm or at least save his dog. Events have a way of spinning out of control like contract you can't get out of no matter how hard you try. There is no such thing as chance, Jim decides, no such thing as chance at all.

Jim hears what he thinks is a low growl coming from under the car. It's sound he's heard before, in the woods, the sound of a wolf gone mad. Jim opens and shuts the car door and waits. Whatever was under there is gone. He walks out of the drive house and lights a cigarette.

Noticing the barn door open halfway, Jim walks over to it. When he steps inside and looks for Boxer on the floor and sees only the empty space where the dog had lain, for a moment, the thrill of a second chance overcomes him. He decides right then and there he will do whatever it takes to keep Boxer alive; if he can't get the dog a good home, then Boxer will come with them to the city.

As Jim runs toward the house to tell Vye, he hears the growl again. He turns and finds Boxer, teeth bared, foaming at the mouth, and ready to attack. Vye appears at the screen door. She cups her hand over her mouth while Jim speaks softly to the dog. —Boxer, it's me. Where's my good boy? Where's my dog? Boxer.

If the dog recognizes Jim, he doesn't show it.

Vye heads to the Reeves for a gun. There is no time to get the vet. Jim stands still holding his breath barely keeping the dog at bay.

When Vye returns with the gun she passes it to Jim, and the dog doesn't seem to notice. Jim holds the rifle the way a surgeon holds a knife before he cuts. His hands are steadier than they've been all afternoon. And dry, it surprises him that his hands are dry. He points the gun at the head of the frothing and mad animal before him. He touches the trigger. The metal is cold and smooth. He can hear everything and nothing at once. A bird drops a twig on the rear of the car, and to Jim it's as loud as a branch falling from a tree. But Boxer's growl, which he knows is loud, sounds to him as muffled and soft as breathing. He shuts his eyes and stands for a moment, unmoving.

Then, Jim puts the gun down. Whatever fire Boxer has left, Jim cannot be the one to smother it. Without looking at her husband, Vye gently removes the rifle from Jim's hand. She raises it slowly, methodically, and then aims at the dog. She's a good shot. She's been shooting at tin cans ever since Jim can remember. As he walks toward the farmhouse, he hears the bullets leave the gun and break the dog's flesh like stones.

Jim sits on the edge of the bed waiting for everyone to leave the yard. Reade Reeves is shoveling the last of the dirt over Boxer's grave. Jim can see this from the window, and he knows this will be one of those moments he will remember for a long time. He will remember the bed squeaking when he leaned toward the window to watch his neighbour burying his dog and how the quilt felt as he clutched the side of the bed. He will remember wanting to crawl under the covers, wanting to shut his eyes and forget his whole life but not wanting to muss the bedding that Vye washed and ironed and made up only this morning.

The news of Vye shooting Boxer because he couldn't has spread through the entire Reeves clan so that now Reade's daughter is standing on the grass beside her father, watching. Watching, if Jim can believe his eyes, with a finger up her nose. He thinks she's the one who wets the bed every time she stays over the night. So much so that Vye's taken to laying down green garbage bags underneath the sheets.

Though he should be relieved this will be the last time he will see her, he is not. He's as resentful of her standing by the barn, picking her nose over Boxer's grave as he would be if she were sitting here pissing on Vye's clean sheets. Jim puts his hand over his face. He can't watch this. He can't wait for them to leave. It will be a whole new life he tries to console himself. It will be a whole new life when they move to the city.

Vye comes out of the house with lemonade and small bowl of sugar cubes. Reade, who has just finished with the grave, wipes his brow and accepts the drink thankfully. Later, Vye will say, —Wasn't that nice of Reade to bury Boxer? But what she will mean is he should have done it himself. He would have if everyone had left the yard. Jim had wanted to bury Boxer, but Reade just took over. The same way Reade's father, Clive, took over all those years ago. Though he knows it shouldn't, it burns Jim that the Reeves are so good. Is Jim good? Vye would say that he was, but Jim doesn't know. He doesn't think so.

It's been almost an hour since Vye shot Boxer, and Jim realizes this will be how he measures time from now on. As it was when his father died, so it will be again—one chapter closes, another opens, not necessarily better than what came before.

Originally published in Prism international, Issue 41, 2002Kathryn Mockler is the author of the story collection Anecdotes (Book*hug Press, 2023), which was a finalist for the 2024 Trillium Book Award, the 2023 Danuta Gleed Literary Award, the 2024 Fred Kerner Award, and the 2024 City of Victoria Bulter Book Prize. She co-edited the print anthology Watch Your Head: Writers and Artists Respond to the Climate Crisis (Coach House Books, 2020) and runs the literary newsletter Send My Love to Anyone. Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

September 30, 2024

3 poems from "she"

Poets Jérôme Melançon & Kirby on the balcony.

Poets Jérôme Melançon & Kirby on the balcony.Send My Love to Anyone is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support this project, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Poet, Jérôme Melançon and I met, quite by chance a couple of years ago. They were in town for a conference (“profs who always find ways to work more...”) and emailed he was sad to have missed knife | fork | book as a physical place, asking for bookshop recommendations, and, missing KFB as a place myself, I invited him over since my living room is the next best thing. We lunched on the balcony, I supplied him with poetry and he was kind enough to write about his engagement with Poetry is Queer (later posted in Carousel Magazine). We’ve been in touch sporadically since then.

Then, one morning, I woke up to these beauteous translations by Jérôme to three poems from my new collection, she. It’s the first time (I’m aware of) my work has ever been translated (here, from English to French) and we’re delighted to share them with you. Enjoy.

GrisText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publisheddans la pluie du villageles tablettes de pain de la veille vides presqu’une piastrepour un oeuf mains se tendent pas de sous sur la rueon ne peut pas taper une main se cogne rien là làrien la communauté électronique ne crée riencette affaire supposée être la grosse affaire pasla moindre affaire maintenant la seule absent tout à coupassis ici sans soupçon sans envie sans goûtd’aller où n’importe ou parké à un serviceà l’auto une cloison un cubicule à part je ne pouvais pascroire que ça existerait pour une raison humaine “qu’est-ceque cela veut dire ici? Humaine?” Amir le chercheen farsi écrase sa cigarette exhale.“Oui, oui, c‘est ça.”Milieu de nulle part [Ohio]Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedjasmin-trompette rafraîchit retournele ciment du patio trous champlibre aux tamias jardinsà peu près disparus une énormemauvaise herbe mi-trottoir de nouveauxpropriétaires des jeunes s’en occuperont“mérite d’être entretenu” comme lamaison sur Paisley une autre sur une collineque nous ne pouvions pas nous payer suffisamment d’espace croissancede la famille trois sortes de lilacs des asperges des champs sauvageshautes comme ses genoux jamais n’ont été aussi douceselle pense que nous ne nous souvenons de rientrempant son pinceau dans l’eau verte bleuâtreverre en styromousse du magasin à un dollar.GentillesseText within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedAttend de monter dans l’autobusporte d’en arrière avec passeoù le sentier est dégagé.Le conducteur qui n’ouvre pas la porte.Traverse la glace pour aller àla porte avant, glisse tombedur, glisse sous l’autobus.Le conducteur qui ne fait rien.En montant on me voit,“Attendez!” On me redonnemon chapeau,“Est-ce que ça va, monsieur?”C’est exactement comme cela que ça arrivera.Les derniers mots que j'entendrai.Une étrangère qui me prend poliment pour monsieur.Jérôme Melançon writes, teaches, and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. Chapbooks include, Bridges Under the Water (2023), Tomorrow’s Going to Be Bright (2022) and Coup (2020) above/ground press, and the poetry collections, En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021), De perdre tes pas (2011) and Quelques pas quelque part (2016) both Éditions des Plaines. His social media handle is @lethejerome.

Kirby’s she is out now from knife | fork | book and can be found at your local or request it at your library home branch and/or at Asterism Books.

See Kirby this fall at Poetry Weekend (Fredericton Oct 5&6) Harbourville NS Oct 11 (w/Jessica Joy Hiemstra & Cory Lavender) The Trident (Halifax Oct 12) w/Sue Goyette.

Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

September 27, 2024

Phoebe Wang | Issue 40

Will I make it will I make it will I?

It’s a few minutes past five on a sharp spring afternoon. I gaze ahead at the dove-grey slice of lake. It’s not far, but there are so many crosswalks and intersections slowing me down. Every time a big red hand goes up, I’m forced to stop running. I suck in big breaths of air, check my phone, and wedge my body ahead of the other pedestrians. People—there are so many people in my way. Office workers power-walking to Union Station, tourists walking three or four abreast, couples arm in arm, Blue Jays fans clogging York Street near the stadium. I jog underneath the Gardiner Expressway and across streetcar tracks toward the waterfront. To anyone watching, I look like another irritable, impatient Torontonian. I feel like I’m fleeing and chasing something at the same time.

I’m going to make it. The Algonquin Queen II is rounding the Sundial Folly sculpture and pulling up at the dock. A biker dings his bell through the seagulls and club members with Sobeys bags flapping at their feet. I’ve made it. I fill and refill my lungs while looking out at the lake criss-crossed by island ferries. In the early part of the century, the harbour was crowded with docks, wharves, and sheds, and watercraft of all shapes and sizes—paddle steamers, passenger steamboats, lumber carriers, skiffs, and, in winter, iceboats. But today, I take in a view uncluttered by history.

Still out of breath, I join the loose hoop of members and guests waiting for Queen City Yacht Club’s tender boat. The schedules aren’t a secret, but since only members or their guests can book a ticket and board the tender, not many Torontonians know about these club ferries. On race nights, the tender runs every half-hour and drops off passengers right in front of the club on Algonquin Island. There are other options to reach the island, such as the city ferries or the water taxis, but they’re not as convenient or as pleasant. Following an unspoken etiquette, we wait while people with bikes and grocery carts board first. Senior members flash their membership cards and board while the rest of us line up to pay with cash or tickets. The Algonquin Queen II has a capacity of forty-nine and I have to admit I like the feeling of exclusivity. As I slowly move down the ramp to the tender, I leave behind another Phoebe, the stressed-out, overworked Phoebe, like a shadow that cannot leave shore.

During sailing season, I hurry from tutoring centres and ESL schools and offices across the city. I bike from different apartments to arrive on time. I arrange work schedules to have Wednesday evenings at liberty, and when I can’t leave students or escape a meeting early, my mind wanders to the lake, where the rest of the crew are unwrapping lines and sails. From early May to late September, sailors around Lake Ontario understand these rituals. We pack bags with Sperrys, sunglasses, lanyards, sunscreen, gloves, and snacks. We dress in layers. We text boat owners looking for extra crew. We work through lunch so we can power down our laptops at 4:00 p.m. to get over to the island and ready our boats before the race committee makes its starting signals. We don’t take this for granted. Sailing season is short as a Canadian summer. A change of state comes over me when, after a prolonged winter, I step onto the tender and feel its tilt and sway. I’m on the water now. I stand among chit-chatting crew. If I’m in a social mood, I’ll ask after kids and winter vacations. But often I’m silent, watching the city retreat and squinting to see if I recognize any of the Vikings and Beneteaus heeling on the lake. I note the wind direction and the stack of clouds over Humber Bay. I estimate how many knots of wind might be fanning the tender’s flag, though when the sun lowers, it’ll inevitably drop off.

There are many rituals. In the weeks leading up to launching their boats, owners don workpants and old sweaters. They’ll climb ladders to their boats nestled high in their cradles and peel back the covers, hoping not to find too much ice in the cockpit or to have to evict a family of rodents or birds. Rubbing their chilly hands, they’ll start investigating for dampness, rot, mould, and rust, adding to the list of repairs and tasks made when the boats were hauled out of the water at the end of last season. As the ground warms and the trees start to bud, the boatyard will become vocal with hammers, sanders, and the occasional bad word. Owners depressed and flummoxed by a task can usually find a sympathetic ear, a bit of advice, a spare part, or all three. Owners who left their boats in good repair take pleasure in the brightwork and polishing and varnishing the wood trim. On launch weekends, teams of senior members push each boat cradle onto rails so they can be driven down the marine railway and launched with their owners sitting in the cockpits like minor royalty on a parade float. Eager to be in the proximity of a sailboat again, I too have done my bit of sanding and painting of keels and hulls. Though I’m not a boat owner, I’m just as impatient to see them afloat again, lined up in their moors and slips.

After a fifteen-minute crossing, the Algonquin Queen II draws up alongside the white-painted, two-storey clubhouse. My gaze takes in the balconies and planters of flowers. I thank the crew as I step onto the dock, make my way to the club washrooms for one last stop, then shortcut along the marine railway toward the south gate. I pass the bigger boats in their slips, the cottonwood trees that drop sticky yellow buds each spring. The long line of masts shifts in the breeze along Algonquin and Ward’s Island, accompanied by the tinkling sound of metal snaps and stays. Boats that don’t race expectantly await their owners, like unopened gifts. I pass other crews unplugging extension cords and unzipping sail covers. When I reach Panache, the 26-foot Niagara I crew on, I don’t have to ask permission as I step over the lifelines and onto the deck.

Mark, the owner and skipper, feels my weight on the boat before his eyes crinkle in greeting. Because he is my friend and roommate, I frequently ignore and make fun of him, but because he is also my skipper and the person responsible for steering the boat and instructing the rest of us to carry out manoeuvres, I have to pay attention to him. We grin at each other in silent acknowledgement of this shift, then he continues a story he was in the middle of telling to Phil or to Pat, already on board. I leap down to the cabin, stow my knapsack on the floor, put my beer in the locker, and peer up at Mark with jib sheets under my arm.

“There was a lot of breeze in the harbour,” I report. “We’ll go with the number two then,” Mark says, lowering the outboard motor and plugging in the fuel line. Handing the jib sheets to Phil, who starts unwrapping them, I find the right sail and haul it up onto the foredeck, or the bow of the boat, unzipping the bag to find the tack and clew ends. I clip the jib to the forestay with the snap hooks along the edge of the leech, then sit on the deck tying bowline knots on the jib sheets, which I run outside of the shrouds but inside the lifelines, through the blocks, loosely around the winches, ending with a figure-eight knot to keep the lines from sliding out. This was the first knot I learned, and I can make them without thought now.

In my first season crewing, I felt a plunging disbelief that I was able to spend time on a sailboat, and the feeling still hasn’t quite left me. I didn’t grow up sailing, and I believed that no one in my family had either. But my parents are islanders, and my mother tells me that my great-grand-mother lived on a houseboat in Hong Kong’s Aberdeen Harbour. Like most people unfamiliar with the sport, I imagined uniformed crew outfitted in hundreds of dollars worth of Gore-Tex, moving in coordination on a huge yacht slicing through ocean waves. I imagined millionaires’ playthings, Olympic athletes in bright jerseys, and lone, eccentric teenagers embarking on oceanic journeys.

I’m not old, white, or rich. I don’t think I fit anyone’s expectations of a sailor, as evidenced by the looks of surprise I get when I bring it up to family, friends, and fellow writers. Their assumptions exhaust me, and I don’t always have the energy to explain how I began racing, how active the sport of sailing is on the Great Lakes, or the special atmosphere at Queen City. As a result, some people have known me for years and not known that I’ve sailed. In the mirror is a petite Asian woman with a round, serious face who looks like she spends more time in the library than doing rigorous physical activity. Peering closer, I see the bruises on my shins and my foul-weather gear hanging on hooks. But on occasion, someone corners me with their curiosity. “I hear that you sail,” they say, and the words spill out of me. They ask how I started, where I sail, whether it’s an expensive sport. I watch for bewilderment or eyes glazing over at the stream of boat words that I can’t help using and that I try to define for them, but curiosity is a hatch I could pull someone through to a club visit or race, where they too might surprise themselves.

I tell people that QCYC is one of the oldest sailing clubs in Toronto, as comfortable and informal as a hoodie softened by the sun. There’s no dress code—I sail in a uniform of old jeans and a ball cap, and my foul-weather gear consists of a $20 pair of rain pants, hand-me-down gloves of dissolving leather, and a Columbia hiking jacket. No makeup, just sunscreen and my hair in a ponytail. Nor is there a need to be particularly athletic, though it helps. Racing is a few compressed minutes of adrenaline-inducing activity interspersed with long intermissions of sitting, crouching, waiting, and watching.

On a racing boat, there’s a variety of roles to suit strength, agility, and ability. These roles can include skipper, tactician, mainsail and jib sail trimmers, and foredeck, which I’ll explain in more detail later. Among my assets as a sailor, other than my ass itself, which is useful for ballast, is that at five foot three-and-a-half inches tall, my low centre of gravity makes me comfortable balancing on the foredeck. Generally, there aren’t many women who helm or crew on race nights, and even fewer women of colour. Members nod and smile at me in recognition, and I wonder if that’s because there are so few Asian Canadian women my age in the community. I’m used to the visibility and foreignness of my body, having attended literary events and art openings for decades where I’d hardly see another Asian woman. I enjoy undoing other people’s expectations, and even my own.

I didn’t expect to move to Toronto in the summer of 2008—my intention was only to stay a few months. I sublet a room in a Bloordale duplex full of ex-New Brunswick actors and musicians. Shortly after I’d moved in, one of my new roommates invited the household for a sail on a second-hand boat he’d bought the year before. Mark had saved for a year on his “peanut butter and jelly sandwich plan.” It turns out that it’s possible to buy a boat at the age of thirty by saving for a year, not eating out, and living with roommates, so his oft-told story goes. He’s a Maritimer, so tall tales and storytelling are his heritage. Though we’d barely interacted—I was working three jobs at the time—I eagerly responded to his invitation. All I remember of that sail is the evening light on the waves, the laughter of my roommate Amber, her best friend Michelle, and Mark, who was steering us into the middle of the harbour. I hadn’t yet made up my mind about living in Toronto, but being on water gave me a feeling I’d been searching for. The next spring, when Mark sent out an email inviting friends and roommates to crew the club’s Wednesday-night races, I started showing up. That’s how I tell it. I have a sailing story now. And sailing stories are the best stories.

With just half an hour before the race starts, it’s time to get off the dock. Amanda and Tim hurry aboard as I step up to the bow to find the mooring lines beneath the weight of the jib. I unhook and hold them taut while Mark starts the motor, and only when he gives me the go-ahead do I toss the lines onto the grass. Panache backs slowly out, jostling the boats on either side of us with her bumpers. Other crews wave to us, wishing us a good race and a good time. Some yell out a joke that is lost over the sound of the motor. We keep buoys to port and motor past the Ward’s Island ferry dock, where passengers watch us and sometimes wave or take our photo. When we’re in sight of the race committee boat, Mark shuts off the engine and tells us to hoist the sails. We pause our chatting to fit the handle into the main halyard winch, pulling and grinding, tilting our heads back to see when the sail reaches the top.

What makes a crew? When do we become a crew? Is it the moment we step onto the boat, performing our various duties? Or is it when we adjust the sails so that they fill out, the boat heeling with the force of the breeze? I’m not sure. I do know at some point I stopped being a passenger. I became— am becoming—a maker of knots, a trimmer of stories.

Published with the permission of Assembly Press from Relative to Wind: On Sailing, Craft, and Community by Phoebe Wang.© 2024. Phoebe Wang is a first-generation Chinese-Canadian currently based in Toronto, Canada. She is the author of the poetry collections Admission Requirements (McClelland and Stewart, 2017), shortlisted for the Gerald Lambert Memorial Award, the Pat Lowther Memorial Award, and nominated for the Trillium Book Award, and Waking Occupations (McClelland and Stewart 2022). Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The Globe & Mail, The New Quarterly, Brick and The Unpublished City, shortlisted for a Toronto Book Award, and she co-edited The Unpublished City: Volume II, The Lived City. She is currently on the editorial board with Brick Books. She has been a mentor with Diaspora Dialogues and is an adjunct professor and mentor in the University of Toronto Creative Writing MA program. Wang lives and sails in Toronto, Ontario. Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

Relative to Wind: On Sailing, Craft, and Community

by Phoebe WangAssembly Press, 2024

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

Relative to Wind: On Sailing, Craft, and Community

by Phoebe WangAssembly Press, 2024A lingering, long-haul collection of writing about sailing for readers of Julietta Singh and Kyo Maclear.

In Relative to Wind, Phoebe Wang delivers a poetic rendering of her decade-long journey of learning to sail and a deep dive into what it means to be a newcomer to an old tradition. From working alongside crewmates in tempestuous conditions to becoming an avid racer and organizer to drafting a wistful love letter to a Wayfarer dinghy—while examining the loose tether between sailing and a creative life—Wang delivers a book for sailors and would-be sailors that is thoughtful and surprising at every tack.

"A thoughtful, illuminating look at life away from land."—Kirkus

"Although it takes place mostly on the water, Phoebe Wang’s absorbing Relative to Wind covers a lot of ground. In formally inventive chapters, Wang touches upon the history of sailing, the legacies of colonization and discrimination, the emergence of North American yacht clubs, and the evolution of Toronto’s waterfront. She does so with poetic prose."—The Literary Review of Canada

“A riveting book about our parallel lives, the side passions that steer our hearts and right our balance. I am not a good sailor, have honestly rarely sailed, but I can say without hesitation that you will not find a book that better captures the sport—or the vagaries of wind, collaboration and creative practice. Phoebe Wang’s expansive prose is wise and guiding, and I was very happy to have travelled with her.”—Kyo Maclear, author of Unearthing

"Wang's book demystifies sailing and the process of learning to sail in a fresh and inviting way. Her story will encourage anyone inclined to step on a boat without experience, and her perspective paves the way for much-needed diversity and accessibility in the sport. Her love for this new nautical world reminds all sailors why we yearn again and again for the wind to fill our sails."—Captain Liz Clark, author of Swell

“For readers like me who are unfamiliar with the intricacies of sailboat culture and its boat speak, poet Phoebe Wang offers a headlong introduction into the world of winches and jib sheets. Relative to Wind is an obsession turned lyrical meets technical that sails into the gust with no looking back.”—Amy Fung, author of Before I Was a Critic I Was a Human Being

Support Send My Love to AnyoneSupport Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

September 19, 2024

Book Giveaway to help Palestinian Families in Gaza - Donate by October 31!

Finalist for the 2024 Fred Kerner Book Award

Finalist for the 2024 Trillium Book Award

Finalist for the 2023 Danuta Gleed Literary Award

I'm hosting a book giveaway for two GoFundMe Campaigns to help two Palestinian families. Email me a receipt of your donation of 10 dollars or more and you will be entered in a draw to win a copy of my story collection, Anecdotes.

Abdalaziz Abuaskar’s Campaign

Abdalaziz Abuaskar is organizing this fundraiser on behalf of his cousin, Azza.

Azza is a school teacher and Mohammad is a pharmacist. Both Azza’s school and Mohammad’s pharmacy were destroyed. They have four children and Azza is 6 months pregnant and has asthma. Join me in donating to Azza and Mohammad’s campaign.

Yasmeen Ouda’s Campaign

Yasmeen Ouda moved to London, Ontario from Gaza City four years ago with her husband. She is running this campaign on behalf of her brother who is expecting his first baby and her sister, a 4th year medical student. She hopes to bring them to Canada through a program initiated by the Canadian Government. Join me in donating to Yasmeen Ouda’s campagin.

If you donate at least 10 dollars to either of these fundraisers by October 31, 2024 and email me your donation receipt, you’ll be entered in a draw for a signed first edition copy of my book, Anecdotes, which was a finalist in the Duanta Gleed Prize, the Trillium Book Award, and the 2024 Fred Kerner Award.

This giveaway is available to Canada and US residents.

I found out about these campaigns from Gaza Funds and Operation Olive Branch where you can organize your own fundraiser.

ConnectBluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA