Mary Sisson's Blog, page 119

April 24, 2012

Two hours of sleep and a sick kid...

...left me with some free time but no ability to concentrate. So, I noodled with the flyer (I think I'm going to slap a big ole portal on there) and tried to set things up so that I can waste time on-line more efficiently by plugging most of the blogs I look at into the RSS feeder. I also had to fix Twitter: TweetDeck stopped working for me, only God knows why, and I really hate the regular Twitter interface (honestly, it's slow, it's clunky--when multiple companies exist selling new interfaces to your Web site, that means yours sucks). So I went to HootSuite, which seems to work fine.

I also am trying to get it together to query reviewers, but that above-mentioned problem with concentration is making it hard to...what was I talking about?

The hardening of a position

It's been interesting for me to read the recent posts by Dean Wesley Smith and Kristine Katheryn Rusch and Lawrence Block, because they're all basically saying that, at this point, they wouldn't bother to traditionally publish a novel. This is definitely a shift--before they were of the "Why not keep a foot in both camps?" mentality, but now they're saying, gee, the contracts are really bad and the money really sucks and there aren't actually any advantages to being traditionally published.

And I've had a similar shift: Obviously, on a personal level I had already decided against trying to be traditionally published by a small press in favor of self-publishing, but when someone like Amanda Hocking got a traditional publishing contract, I said rah-rah! There were people whose reactions were more like, OH NO, but I thought they were being unduly negative.

But now, I've realized, my reaction would also be OH NO. And I was wondering why that is--is it just the echo-chamber effect? Is it a reaction to all the stupid anti-Amazon stories out there?

I think, though, that it's more a reaction to recent events, and their implications.

Event #1: The DOJ's agency-pricing lawsuit. What bothered me about this was just how stupid the publishers were. They did something that was quite obviously illegal, and they did it very publicly. And now, predictably enough, they're going to have federal prosecutors climbing all over them for years to come, which is not going to be good for business.

And why did they do it? Well, the world was changing, and they couldn't cope with the changes.

Do you how bad that is for a business? What this means is that they looked at the future, and they saw no room for themselves. They looked at industry trends, and they looked at their own particular business model, and they said, "Holy crap, we're going to go under."

That is their take on the situation. They are expecting disaster. And what they did in their panic can conceivably only make that disaster worse.

I don't know about you, but I'd rather not sign a long-term contract with a company that believes it is going to go under, especially since, if they do, I may never get my book back. They may be wrong about their prospects, but it's never a good sign when a business is expecting the world to end.

Event #2: The IPG/Amazon debacle. Seriously--your publisher's choice of distributor could cause you to lose half your income? How the hell can you protect yourself against something like that? You could do background checks until the cows come home and it's not going to help you. "Hey, Ted, don't worry, we've been in business for 40 years, we're very respectable, and our distributor is a totally above-board industry leader. Oh, sorry about those Kindle sales--sucks to be you! Good luck with the foreclosure!"

Event #3: Gee, we can't sell your book after all! Yeah, Boyd Morrison--he may not actually have to pay back that advance, but it's hardly a happily-ever-after ending here, is it? More importantly, it points to the serious limitations of traditional publishers--with their high costs, they can't afford moderate successes, and they can't reliably create major ones.

Event #4: Math is your friend. Oh my God, the post I did guesstimating Stephanie Meyer's share of the Twilight money in 2010. Holy crap. What's the upside supposed to be, again? Against all odds, you write a huge blockbuster and your publisher keeps 90% of the money, if not more? Isn't this the reason pimping is frowned upon?

And don't say, "Well, she got $21 million, she should be happy!" ("Yeah, bitch, you got your 10%!" Slap!) There is a pot of money there. It exists. The question is simply, how should it be divided? The $160 million Meyer's publisher took did not vaporize or go to charity or anything--it went into the pockets of publishing company executives and shareholders, who have no greater moral or ethical claim on that money than the woman who created those books out of thin air.

April 23, 2012

I was a little productive

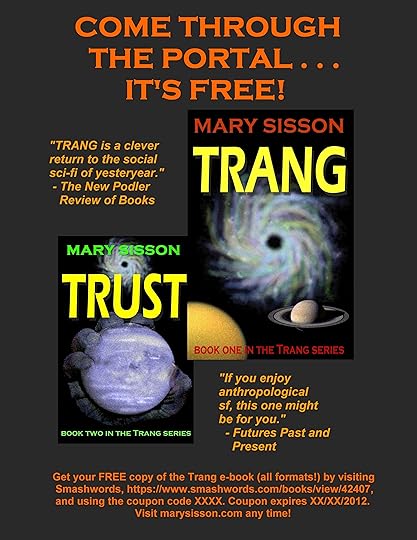

I made up a flyer for when I go to sci-fi cons. I'm still noodling with it, but this is the general idea.

Writers' incomes

The other night I was hanging out with a group of writers and would-be writers. One of them was a self-published novelist who is making a living that way. And she was talking about how it's pretty amazing to see these "self-published midlisters, who are making $10,000 a month, while a traditionally-published midlister...."

"Would be making $10,000 a year," I finished. (I wasn't interrupting, I swear. She had trailed off.)

Anyway, the majority of the other people there had little to no experience in publishing, and they were all shocked by what I said. A published author! Making $10,000 a year! A pittance!

And it is, of course, but that's not an unrealistically low number. Between my work background and the fact that I have befriended a lot of literary types over the years, I know quite a number of people who have had books traditionally published, in many different genre. Romances, memoirs, journalism, fiction, nonfiction--you name it. Good books, too!

None of those people have been able to quit their day job and write books for a living. None of them.

Which is why, when self-published writers are able to go from "no books" to "quit the day job" within about a year, it astounds me.

It's one thing for someone with a huge backlist and an established fan base to become successful. It's one thing for someone to get lucky and hit the jackpot with a runaway bestseller. But for people who have no big hits, and who aren't coming into this business with a big infrastructure behind them, to be able to make a living, oh, a year or so after publishing their very first book--that is amazing.

No-progress report

Yeah, sorry--it's supposed to rain tomorrow, so I had to go leak-hunting (this is one of the things with the house that is going to require an expensive permanent fix--yes, there are others) and I took care of some stuff in the yard while I was at it. In the process I got to deal with a lovely lady at Home Depot who wanted to make sure I had "someone at home" to help me carry all those bulky things I purchased, because, of course, one can't carry things and ovulate at the same time.

After adding that blog archive, I looked at it and thought, Jesus, I blog a lot! Imagine if I put all that effort into writing books instead! But the thing is, if you look at the months when I wasn't blogging much, I wasn't writing, either. Again, I think lots of blogging is just a sign that I am in Book Mode....

If you're looking for a little background....

The Wall Street Journal has a great article on U.S. antitrust law and how Apple & Co. really, really violated it very badly with their agency-pricing agreement. If you can't read it, Passive Voice has an excerpt. It's really worth reading, because one of the basic premises of U.S. antitrust law is that it's geared toward protecting consumers, not businesses--"competition, not competitors" in the words of the article. If you don't understand that basic concept, nothing that antitrust regulators do will make any sense.

And the article notes that books are not really all that special:

Even if publishers did seek an exemption [from antitrust law], it isn't clear that lawmakers would agree that consumers should pay more for e-books in order to save publishers or physical bookstores. The list of companies that have vanished at least in part because of digital distribution grows longer each year: Tower Records, Borders, Circuit City, local travel agents. How would Congress decide which ones should be protected from online competition?

"Why this guy and not that guy?" asks Mark Cooper of the Consumer Federation of America, a nonprofit advocacy group. "You'd end up saving everybody."

I would add only that, if you are going to commit a red-flag, must-prosecute sort of offense, have the sense to do so quietly--law enforcement does read the paper.

And this (via PV) is a great history of book publishing and book retail. It manages to be both very informative and very, very, VERY funny. Rusch has a less-funny but equally informative history of what she calls the book trade--how book publishing and book retail affect each other.

I think the larger lesson from this is that the publishing industry has always changed--it's changing very rapidly right now, but change has been constant. What we call traditional publishing has only been the tradition for the past few decades, and in the form it is in now, really only the past 10-15 years. That's why I could peg the publication date of Jodi Picoult's first novel so accurately: She was obviously published when publishing looked more or less the same as it does today but was somewhat easier to enter; ergo, she was published 20 years ago.

April 12, 2012

Same planet, different worlds

OK, I realize that I'm turning into a media wonk here, but.....

Both the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times are running stories on the Department of Justice lawsuit/settlement and its likely impact on book prices.

Here's the Wall Street Journal's take:

The popular $9.99 price for best-selling e-books may be back in a big way soon.

A settlement announced Wednesday between the Justice Department and three big book publishers will almost certainly lead to lower e-book prices on an array of best-selling titles that now cost anywhere from $12 or $13 and more.

Most important for consumers who like to read, it could mean the $9.99 price point championed by Amazon.com Inc. when it kicked off the e-reader market with its Kindle device in 2007 will once again be common.

The $9.99 price for best sellers largely disappeared after Apple Inc. struck deals with major publishers that changed pricing models for e-books, ahead of Apple's release of its iPad and its iBooks digital store. Instead of letting retailers set prices, as they have long done in the print book world, publishers began setting prices—with best sellers usually priced either at $12.99 or $14.99.

And here's the New York Times' take:

The government's decision to pursue major publishers on antitrust charges has put the Internet retailer Amazon in a powerful position: the nation's largest bookseller may now get to decide how much an e-book will cost, and the book world is quaking over the potential consequences.

As soon as the Department of Justice announced Wednesday that it was suing five major publishers and Apple on price-fixing charges, and simultaneously settling with three of them, Amazon announced plans to push down prices on e-books. The price of some major titles could fall to $9.99 or less from $14.99, saving voracious readers a bundle.

But publishers and booksellers argue that any victory for consumers will be short-lived, and that the ultimate effect of the antitrust suit will be to exchange a perceived monopoly for a real one. Amazon, already the dominant force in the industry, will hold all the cards.

"Amazon must be unbelievably happy today," said Michael Norris, a book publishing analyst with Simba Information. "Had they been puppeteering this whole play, it could not have worked out better for them."

It's just beyond parody! Amazon may drop prices...because it's eeeeeevil!!!! Evil puppetmaster Amazon! Poor little mega-billion-dollar publishing companies!

Call me naive, but I am happy that the DOJ is more worried about consumers being taken advantage of than it is about whether businesses are forced to make unpleasant adjustments--and maybe even shut down--in response to change. As for Amazon's eeeeevilness, my feeling about this is that the antitrust people over at the DOJ are now very focused on books. If Amazon starts engaging in predatory, monopolistic business practices, that will presumably get noticed. In fact, Charles Petit (via Rusch) points out that some of the business practices Amazon engages in now are not kosher according to the DOJ's filing--that's the problem when the feds get involved in your industry, everything they do cuts both ways. And of course people don't have to sit around waiting for the DOJ to take action--they can file antitrust suits themselves.

Hey, look! New jargon!

You know, when you write something that generates praise like, "though I can't put my finger quite on why, this book felt surprisingly unique within the genre," you know you are in the realm of Beyond Easy Categorization. There's nothing wrong with this (presuming one exists outside the traditional-publishing matrix), but it does mean that people looking for a neat categorization might get kind of stymied. So in addition to the "60's social sci-fi" thing, I have updated the Amazon, et al. tags to include the Futures Past and Present categorization as "anthropological sci-fi."

No idea if this is a category with traction, but LET'S EXPERIMENT! 'Tis what this is all about!

April 11, 2012

Reporters and their conflicts of interests

David Gaughran has a great post up (via PV) about a recent Salon story about Amazon, in which the fact Amazon donates money to charities is taken as proof that it is "a rapacious, horrible company from top to bottom" and "evil." Gee, I though the fact that Amazon didn't give to charity was proof that it is evil!

(Gaughran also has a good post up about Jodi Picoult's ignorant remarks on self-publishing. I was thinking of posting about that and changed my mind, but the thing that impressed me was that I hadn't heard of Picoult before, and I guessed from her comments that she had first been published 20 years ago. I was exactly right. I'm getting a little too good at this.)

Anyway, the Salon story was written by Alexander Zaitchik. In addition to the terrible news that Amazon does, in fact, give back, Zaitchik notes that Amazon wants to charge traditional publishers more to market their e-books. The publishers are refusing. And then--and this is how you know that Amazon is really and truly evil--instead of providing marketing services for free, Amazon is not providing the services they are not getting paid for! I know--never before in the history of capitalism has a company refused to provide a service that they weren't paid to provide! This post should be rated R because it is just so shocking!!!

Zaitchik is a freelancer who, not at all shockingly, lives in New York City. I've noted a hometown bias with other NYC-based coverage of the publishing industry. And I'll note additionally that Zaitchik has a book out, published by Wiley.

How much do you want to bet that he'd love to get another book contract?

Is this a tit-for-tat thing? I hope not. I would not be at all surprised that Zaitchik has convinced himself that every word he writes is true, and that he honestly believes that Amazon is evil, and not only because they are damaging his prospects of getting another advance check.

But they are. And that's something I think readers need to keep in mind whenever they read anything about traditional publishing--many reporters either have written or would like to write a book. The same thing is true of their editors. If you get a book published, then your profile is higher, and then you can get a job at a fancier publication, sell stories to more lucrative outlets, and maybe even quit your full-time job to write what you want.

And it's still the case that when many people think of publishing a book, they assume that they're going to need a traditional publisher. They have a dog in this fight.

It's a problem in journalism, and I think it's worse because it's often not the sort of explicit conflict that an employer can easily ban. You'll see, say, somebody get elected governor, and then, wow, half the political reporters who covered his campaign go to work in his press office. I doubt that an actual deal was struck, but I think you'd have to be a robot not to have your perceptions and therefore your coverage affected by the fact that you view someone as a potential employer.

Who hit the rewind button?

I'm feeling better and the surprise guest went home, which left me in the same place I was a few weeks ago, with the layout due back from the copy editor soon but nothing much to do in the meantime. So I shot the copy editor an e-mail to see if she was on track to get it back to me mid-April, and the answer is no, the horrible life crap she's dealing with still has her buried, but she promises I will have it in my hot little hands May 1.

On to Trials, then!