Erika Mailman's Blog, page 14

November 11, 2013

News!

It's been a whirlwind the last few days--a trip out of town to see my best friend who I haven't seen in several years, trying to catch up on some pretty hefty freelance deadlines, cleaning our house and getting rid of stuff in preparation for a move, grading a backlog of student essays...oh, and talking to a wonderful editor in New York!

I'm delighted to announce that a young adult novel of mine has been picked up by Michaela Hamilton of Kensington in a three-book deal. The series is about a young American teen and her family who must go live in the ancestral mansion in England, only to learn that it's not....quite...uninhabited. It's Gothic fun and the series is tentatively titled The Arnaud Legacy. We have to come up with a new title for the first book. We also have to come up with a new title for me; this book will go under a pen name to separate my adult fiction from my young adult fiction.

Michaela's wonderful, and I'm so happy my tormented teen has found a home at Kensington.

More later... the book was based on a nightmare I once had.....

. . . . .

I'm delighted to announce that a young adult novel of mine has been picked up by Michaela Hamilton of Kensington in a three-book deal. The series is about a young American teen and her family who must go live in the ancestral mansion in England, only to learn that it's not....quite...uninhabited. It's Gothic fun and the series is tentatively titled The Arnaud Legacy. We have to come up with a new title for the first book. We also have to come up with a new title for me; this book will go under a pen name to separate my adult fiction from my young adult fiction.

Michaela's wonderful, and I'm so happy my tormented teen has found a home at Kensington.

More later... the book was based on a nightmare I once had.....

. . . . .

Published on November 11, 2013 20:10

November 4, 2013

Interview on Illuminations by Mary Sharratt

I’m so happy to host Mary Sharratt today. She and I are both witchcraft authors; her novel The Witching Hill focused on the Pendle (England) witches of 1612. Because of our witchy connection, we presented together at the Historical Novels Society and have developed a warm camaraderie. Besides being a well-spoken advocate for witches, Mary’s a fantastic writer (I also loved her earlier novel The Vanishing Point, set in Colonial America).

Her latest book Illuminations focuses on perhaps the best-known anchoress of all time, Hildegard of Bingen. Anchoress, you say? So…she was a sailor in charge of the anchor?

Her latest book Illuminations focuses on perhaps the best-known anchoress of all time, Hildegard of Bingen. Anchoress, you say? So…she was a sailor in charge of the anchor?No, an anchoress was someone who chose to remove herself from society for religious reasons and often was permanently enclosed in a cell attached to a church. She bricked herself in to meditate, pray, and offer counsel through a window to the outside world. Says Wikipedia,

“In the Germanic lands from at least the tenth century it was customary for the bishop to say the office of the dead as the anchorite entered her cell, to signify the anchorite's death to the world and rebirth to a spiritual life of solitary communion with God and the angels.”

An anchorite is a male anchoress (so Wikipedia messed up! Surprise.)

Hildegard of Bingen (Germany) lived a rich life despite her confined adulthood. Let’s learn more from Mary…

Who was Hildegard of Bingen?

Born in the Rhineland in present-day Germany, Hildegard (1098–1179) was a visionary abbess and polymath. She composed an entire corpus of sacred music and wrote nine books on subjects as diverse as theology, cosmology, botany, medicine, linguistics, and human sexuality, a prodigious intellectual outpouring that was unprecedented for a 12th-century woman. Her prophecies earned her the title Sybil of the Rhine. An outspoken critic of political and ecclesiastical corruption, she courted controversy. Late in her life, she and her nuns were the subject of an interdict (a collective excommunication) that was lifted only a few months before her death. Hildegard nearly died an outcast.

In October 2012, over eight centuries after her death, the Vatican finally canonized her and elevated her to Doctor of the Church, a rare and solemn title reserved for the most distinguished theologians. Presently there are only 33 Doctors of the Church, and only three are women (Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Ávila, and Thérèse of Lisieux).

What inspired you to write a novel about this 12th-century powerfrau?

For 12 years, I lived in Germany where Hildegard has long been enshrined as a cultural icon, admired by both secular and spiritual people. In her homeland, Hildegard’s cult as a “popular” saint long predates her official canonization.

I was particularly struck by the pathos of her story. The youngest of 10 children, Hildegard was offered to the Church at the age of eight. She reported having luminous visions since earliest childhood, so perhaps her parents didn’t know what else to do with her.

Mary Sharratt

Mary SharrattAccording to Guibert of Gembloux’s Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, she was bricked into an anchorage with her mentor, the 14-year-old Jutta von Sponheim, and possibly one other young girl. Guibert describes the anchorage in the bleakest terms, using words like “mausoleum” and “prison,” and writes how these girls died to the world to be buried with Christ. As an adult, Hildegard strongly condemned the practice of offering child oblates to monastic life, but as a child she had absolutely no say in the matter. The anchorage was situated in Disibodenberg, a community of monks. What must it have been like to be among a tiny minority of young girls surrounded by adult men?

Disibodenberg Monastery is now in ruins and it’s impossible to say precisely where the anchorage was, but the suggested location is two suffocatingly narrow rooms built on to the back of the church. Hildegard spent 30 years interred in her prison, her release only coming with Jutta’s death. What amazed me was how she was able to liberate herself and her sisters from such appalling conditions. At the age of 42, she underwent a dramatic transformation, from a life of silence and submission to answering the divine call to speak and write about her visions she had kept secret all those years.

In the 12th century, it was a radical thing for a nun to set quill to paper and write about weighty theological matters. Her abbot panicked and had her examined for heresy. Yet, miraculously, this “poor weak figure of a woman,” as Hildegard called herself, triumphed against all odds to become one of the greatest voices of her age.

What special challenges did you face in writing about such a complex woman?

Hildegard’s life was so long and eventful, so filled with drama and conflict, tragedy and ecstasy, that it proved mightily difficult to squeeze the essence of her story into a manageable novel. My original draft was 40,000 words longer than the current book. I also found it quite intimidating to write about such a religious woman. In the end, I found I had to let Hildegard breathe and reveal herself as human.

If Hildegard has long been venerated as a “popular” saint in Germany, why did it take the Vatican so long to canonize her? Why Hildegard and why now?

The first attempt to canonize Hildegard began in 1233, but failed as over 50 years had passed since her death and most of the witnesses and beneficiaries of her reported miracles were deceased. Her theological writings were deemed too dense and difficult for subsequent generations to understand and soon fell into obscurity, as did her music. According to Barbara Newman, Hildegard was remembered mainly as an apocalyptic prophet. But in the age of Enlightenment, prophets and mystics went out of fashion. Hildegard was dismissed as a hysteric and even the authorship of her own work was disputed. Pundits began to suggest her books were written by a man.

Newman states that Hildegard’s contemporary rehabilitation and resurgence were due mainly to the tireless efforts of the nuns at Saint Hildegard Abbey. In 1956, Marianna Schrader and Adelgundis Führkötter, OSB, published a carefully-documented study that proved the authenticity of Hildegard’s authorship. Their research provides the foundation of all subsequent Hildegard scholarship.

In the 1980s, in the wake of a wider women’s spirituality movement, Hildegard’s star rose as seekers from diverse faith backgrounds embraced her as a foremother and role model. The artist Judy Chicago showcased Hildegard at her iconic feminist Dinner Party installation. Medievalists and theologians rediscovered Hildegard’s writings. New recordings of her sacred music hit the popular charts. The radical Dominican monk Matthew Fox adopted Hildegard as the figurehead of his creation-centered spirituality. Fox’s book Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen remains one of the most accessible and popular books on the 12th-century visionary. In 2009, German director Margarethe von Trotta made Hildegard the subject of her luminous film, Vision. And all the while, the sisters at Saint Hildegard Abbey were exerting their quiet pressure on Rome to get Hildegard the official endorsement they believed she deserved.

Pope John Paul II, who had canonized more saints than any previous pontiff, steadfastly ignored Hildegard’s burgeoning cult, possibly because he was repelled by her status as a feminist icon. Ironically, it is his successor, Benedict XVI, one of the most conservative popes in recent history—who, as Cardinal Ratzinger, defrocked Matthew Fox—finally gave Hildegard her due. Reportedly, Joseph Ratzinger, a German, had long admired Hildegard.

What relevance does Hildegard have for us today?

I think that Hildegard’s legacy remains hugely important for contemporary women. While writing this book, I kept coming up against the injustice of how women, who are often more devout than men, are condemned to stand at the margins of established religion, even in the 21st century. Women priests and bishops still cause controversy in the Episcopalian Church while Pope John Paul II called a moratorium even on the discussion of women priests.

Modern women have the choice to wash their hands of organized religion altogether. But Hildegard didn’t even get to choose whether to enter monastic life—she was thrust into an anchorage at the age of eight. The Church of her day could not have been more patriarchal and repressive to women. Yet her visions moved her to create a faith that was immanent and life-affirming, that can inspire us today.

The cornerstone of Hildegard’s spirituality was Viriditas, or greening power, her revelation of the animating lifeforce manifest in the natural world that infuses all creation with moisture and vitality. To her, the divine was manifest in every leaf and blade of grass. Just as a ray of sunlight is the sun, Hildegard believed that a flower or a stone was God, though not the whole of God. Creation revealed the face of the invisible creator.

Hildegard’s re-visioning of religion celebrated women and nature and even perceived God as feminine, as Mother. Her vision of the universe was an egg in the womb of God.

Hildegard shows how visionary women might transform the most male-dominated faith traditions from within.

What’s next? Do you have a new novel in progress?

I’m working on a new novel, The Dark Lady’s Masque, which explores the life of Aemilia Bassano Lanier (1569–1645), reportedly the Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The highly-cultured daughter of an Italian court musician, she was also an accomplished poet and the first English woman to publish a collection of poetry under her own name.

Mary, thanks so much. I wish the best success for your novel and for the world to get to know Hildegard, who was so deeply extraordinary.

To view a book trailer for Illuminations, click here.

. . . . . .

Published on November 04, 2013 19:49

November 2, 2013

Shelters of the Donner Party

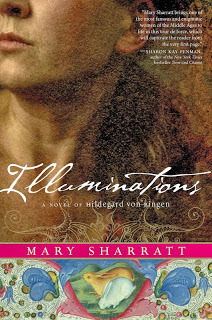

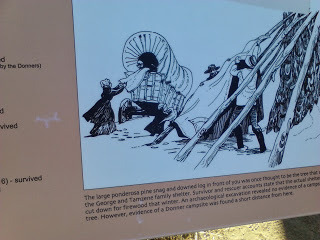

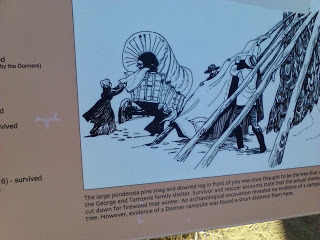

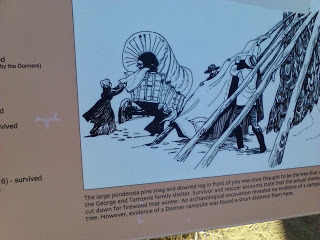

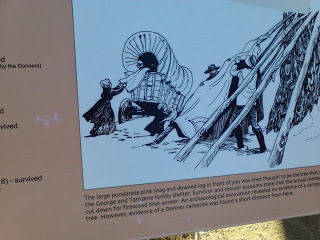

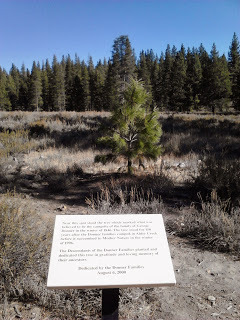

Members of the Donner Party were not all housed together. Far from it. The literal Donners--George and his family, and Jacob and his family, and their teamsters and a few others--fell behind the others and were forced to create makeshift shelters as snow literally piled up on them. They built those shelters at Alder Creek. George and his family built their shelter against a tree. The images show the tree that was long believed (but since disproved) to be that tree, and a drawing of how it could've worked. Jacob and his family built a separate shelter.

The tree? Probably not.

The tree? Probably not.

Building against the tree trunk

Building against the tree trunk

Gratuitous selfie in Alder Creek parking lot

Gratuitous selfie in Alder Creek parking lot

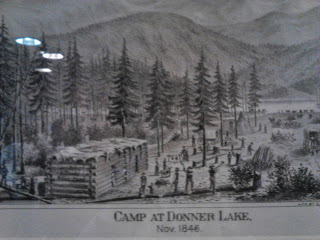

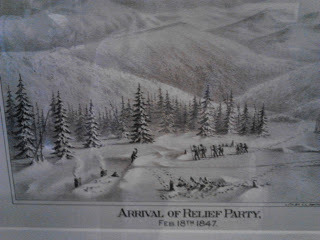

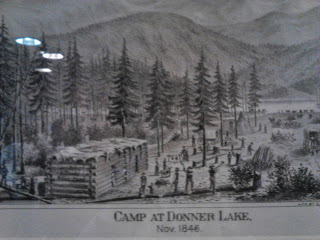

A full seven miles away, on the shores of what is now Donner Lake, three other shelters served the non-Donner members. One was a fairly decent log cabin used by Moses Schallenberger two winters before (like the Donners, he wintered at the lake, and his memoirs make good reading). Patrick Breen and his family were presumably the first to arrive at the lake, and first come-first served. On the site of the Breen cabin now stands the Pioneer Monument, a fairly ghastly depiction of man, woman and child groping their way to California.

Pioneer MonumentFamously, the base of the statue is 22 feet, the snowfall the winter of 1846. Lots of people dispute that number, saying it was the accrued snowfall that melted and refell--that at no time would 22 feet of snow stand. But check out this factoid from Truckee's wikipedia entry: "The maximum 24-hour snowfall was 34.0 inches (86.4 cm) on February 17, 1990." Unfortunately, there were no meterologists monitoring things at Donner Lake that year, but we have reports of unrelenting snowfall from Breen's extant diary.

Pioneer MonumentFamously, the base of the statue is 22 feet, the snowfall the winter of 1846. Lots of people dispute that number, saying it was the accrued snowfall that melted and refell--that at no time would 22 feet of snow stand. But check out this factoid from Truckee's wikipedia entry: "The maximum 24-hour snowfall was 34.0 inches (86.4 cm) on February 17, 1990." Unfortunately, there were no meterologists monitoring things at Donner Lake that year, but we have reports of unrelenting snowfall from Breen's extant diary.

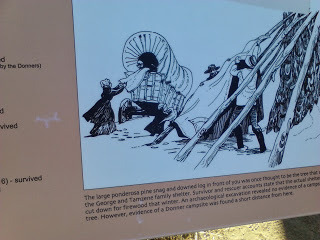

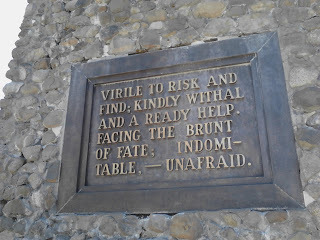

Here's a close-up of the plaque on the monument. I cannot believe it mentions virility, since it was the men who made the disastrous decision to take the fatal Hasting's Cut-off, while poor Tamsen Donner clearly advocated staying on the proven trail. A fellow traveller's journal reports her sour disposition as the men overruled her.

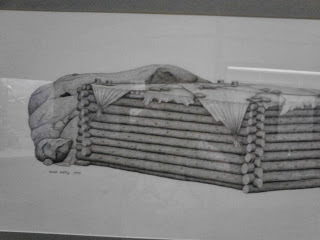

Here's a drawing of the Schallenberg cabin as it might've appeared when the emigrants first arrived, before it dawned on them that they weren't going over that mountain range anytime soon...

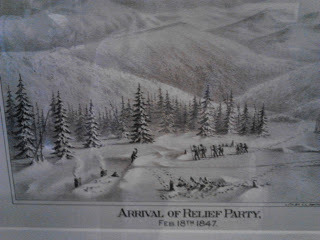

And the same cabin now covered in snow, only its two chimneys visible. Sobering sight.

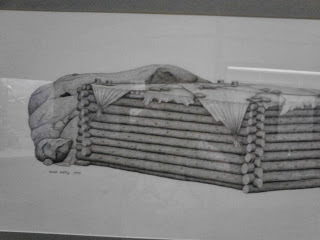

The Breen cabin, windowless, with no true roof and covered by buffalo hides, was the best of the shelters. The Murphy family built their shelter against the side of an enormous rock.

Murphy cabin site with docent

Murphy cabin site with docent

Here's a drawing of how the rock/cabin combo might've worked.

Yet a third structure was built, for the Graves and Reed families. Here's what's so extraordinary. Of course the Donners were far away at Alder Creek; George had become injured fixing his wagon, so they had to stop and reassess. But the families that made it to the lake--why did they build their structures so far apart? After all, there is safety in numbers, especially for people that had seen firsthand how Native Americans could endanger them (major historical irony). Historian Kristin Johnson thinks they were just so exhausted by dealing with each other--after the worst.roadtrip.ever.--that they chose to set their cabins far apart, even if meant terrible slogs through 22-foot snow to reach each other with news or to ask for food.

Standing at the Pioneer Monument (i.e, the Breen family cabin), you can barely see in the distance the tall Shell gas station sign (a yellow blob atop a pole in the center of this photo: look just to the right of the green road signs) which marks the approximate spot of the Graves-Reed site. In the opposite direction, walking from the Breen site to the Murphy site is a good, brisk walk in decent weather, and would be quite an undertaking in snow.

The layout:

Murphy rock ---> Breen (pioneer monument) -------> Graves-Reed

Walking from the Murphys to the Graves? You'd need a car.

At Breen site, looking towards Graves-Reed

At Breen site, looking towards Graves-Reed

Tired of the Donners yet? There's more to come.

. . . . .

The tree? Probably not.

The tree? Probably not. Building against the tree trunk

Building against the tree trunk

Gratuitous selfie in Alder Creek parking lot

Gratuitous selfie in Alder Creek parking lotA full seven miles away, on the shores of what is now Donner Lake, three other shelters served the non-Donner members. One was a fairly decent log cabin used by Moses Schallenberger two winters before (like the Donners, he wintered at the lake, and his memoirs make good reading). Patrick Breen and his family were presumably the first to arrive at the lake, and first come-first served. On the site of the Breen cabin now stands the Pioneer Monument, a fairly ghastly depiction of man, woman and child groping their way to California.

Pioneer MonumentFamously, the base of the statue is 22 feet, the snowfall the winter of 1846. Lots of people dispute that number, saying it was the accrued snowfall that melted and refell--that at no time would 22 feet of snow stand. But check out this factoid from Truckee's wikipedia entry: "The maximum 24-hour snowfall was 34.0 inches (86.4 cm) on February 17, 1990." Unfortunately, there were no meterologists monitoring things at Donner Lake that year, but we have reports of unrelenting snowfall from Breen's extant diary.

Pioneer MonumentFamously, the base of the statue is 22 feet, the snowfall the winter of 1846. Lots of people dispute that number, saying it was the accrued snowfall that melted and refell--that at no time would 22 feet of snow stand. But check out this factoid from Truckee's wikipedia entry: "The maximum 24-hour snowfall was 34.0 inches (86.4 cm) on February 17, 1990." Unfortunately, there were no meterologists monitoring things at Donner Lake that year, but we have reports of unrelenting snowfall from Breen's extant diary.Here's a close-up of the plaque on the monument. I cannot believe it mentions virility, since it was the men who made the disastrous decision to take the fatal Hasting's Cut-off, while poor Tamsen Donner clearly advocated staying on the proven trail. A fellow traveller's journal reports her sour disposition as the men overruled her.

Here's a drawing of the Schallenberg cabin as it might've appeared when the emigrants first arrived, before it dawned on them that they weren't going over that mountain range anytime soon...

And the same cabin now covered in snow, only its two chimneys visible. Sobering sight.

The Breen cabin, windowless, with no true roof and covered by buffalo hides, was the best of the shelters. The Murphy family built their shelter against the side of an enormous rock.

Murphy cabin site with docent

Murphy cabin site with docentHere's a drawing of how the rock/cabin combo might've worked.

Yet a third structure was built, for the Graves and Reed families. Here's what's so extraordinary. Of course the Donners were far away at Alder Creek; George had become injured fixing his wagon, so they had to stop and reassess. But the families that made it to the lake--why did they build their structures so far apart? After all, there is safety in numbers, especially for people that had seen firsthand how Native Americans could endanger them (major historical irony). Historian Kristin Johnson thinks they were just so exhausted by dealing with each other--after the worst.roadtrip.ever.--that they chose to set their cabins far apart, even if meant terrible slogs through 22-foot snow to reach each other with news or to ask for food.

Standing at the Pioneer Monument (i.e, the Breen family cabin), you can barely see in the distance the tall Shell gas station sign (a yellow blob atop a pole in the center of this photo: look just to the right of the green road signs) which marks the approximate spot of the Graves-Reed site. In the opposite direction, walking from the Breen site to the Murphy site is a good, brisk walk in decent weather, and would be quite an undertaking in snow.

The layout:

Murphy rock ---> Breen (pioneer monument) -------> Graves-Reed

Walking from the Murphys to the Graves? You'd need a car.

At Breen site, looking towards Graves-Reed

At Breen site, looking towards Graves-ReedTired of the Donners yet? There's more to come.

. . . . .

Published on November 02, 2013 23:45

October 30, 2013

Halloween posting on witches

I'm featured at Stephanie Renee dos Santos's blog today, part of a three-part series where three witchcraft authors weigh in on the connection between Halloween and witches. (The other authors are: yesterday, Suzy Witten, and tomorrow, Mary Sharratt.)

Click on over to read! The link is here.

The image:

Credit: Brian Levack: The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe (Longman 1987)A demon encourages witches –including men—to trample the cross, depicted in the 1610 book Compendium Maleficarum, by an Italian monk.

Published on October 30, 2013 09:25

October 27, 2013

The movie Donner Pass

A few nights ago, I watched "Donner Pass," since it streams for free on Netflix. I want my hour and a half back. Besides being a hardly-scary horror movie (they filmed some stuff in broad daylight, which was so corny it was laughable....at least give us some darkness to lend an air of fright. I guess it's harder to figure out lighting in night scenes and this was a low-budget film.)

But instead of taking pot shots at its quality (two words: fish and barrel), I'd like to focus attention on something far more deplorable. In the opening scene of the movie, George Donner shoots three other men and sinks to his knees to ferociously rip out their innards and eat them.Worse, modern-day characters later say that he lured the party to the mountains to eat them.

Really? George Donner? That poor elderly man whose world came to a halt after his hand got cut? Antibiotics would save his life today, but in 1846 he and his family had to hunker down in the snow at Alder Creek, seven miles from the rest of the people trapped at Donner Lake, while the infection traveled from his palm to his shoulder and killed him. He made a lot of mistakes, but undergoing endless months of strength-stripping travel simply to feast on flesh at the end does not make a lot of sense.

The Donner Party people were victims. They did not kill each other to eat (oh wait, yeah, it's believed a small subgroup of the party, far from the camps and trying to make it out through the pass, did intentionally murder Luis and Salvador. And those were two men who had come in relief parties to try to help them. Horrible! But the people trapped in the camps only ate flesh of corpses, and that with great reluctance.)

They were victims. They were starving to death, trapped in snow so high that they could barely walk. Try to hunt in that. Try to cut down a tree for firewood in that (it sinks down through the snow and you have to dig to retrieve it). Try to locate your lost cattle in that so you can eat their frozen carcasses--you won't be able to find them although you'll endlessly try with a nail stuck to a pole, sinking it into the snow and hoping to feel the pole stick on something.

A movie like this is kind of like a movie about the Titanic disaster in which the people deliberately try to drown each other with demented glee.

This movie made me outraged on behalf of the Donners. Had I lived through such suffering, I would be bitter that the circumstances of my months of terror were now fodder for a cheap horror movie.

. . . .

Published on October 27, 2013 01:20

October 21, 2013

Halloween op/ed

Witches burn town in 1610 Compendium Maleficarum

Witches burn town in 1610 Compendium MaleficarumI've posted this before, but as Halloween is approaching, I'd like to take a break from the Donner Party and switch gears to witchcraft. Here is a link to my op/ed on our modern take on witches at Halloween time. It appeared in the Chicago Tribune in 2008 and several other newspapers nationally.

Ding, Dong, The Witch Isn't Dead

Last October, my neighbor stretched synthetic cobwebs among the branches of her tree. Against this creepy backdrop, she hung a broomstick and a badly made female figure, clearly a witch. The sight made me wince.

How did we evolve to find this display lightly amusing? Our forebears did hang women from trees. I imagine the devastation a time-traveler might feel as she realizes people crudely pantomime the appalling circumstances of her death each Halloween.

body{margin:0px;}

body{margin:0px;}

I may take this more personally than some. Townspeople accused my ancestor, Mary Bliss Parsons, of witchcraft in Massachusetts, three decades before the Salem hysteria. The court acquitted her, but neighbors pointed the finger at her again, 18 years later. I imagine she never relaxed in the interim. When the woman in the next cottage averts her eyes because she believes you know the devil, you can't exactly run over to borrow a cup of sugar.

Surprisingly, the courts freed her a second time. Our stereotype of witchcraft times presumes that once someone is accused, they are sure to hang (or burn, if in continental Europe -- England and New England were the only places that did not burn their witches). But magistrates acted fairly reasonably, releasing more than a quarter of the accused in 17th Century New England, according to author John Putnam Demos. Due to luck or power, my ancestor walked past the tree that might have hanged her.

Twice.

Scholars argue about how many executions occurred during Europe's 400-year holocaust (consider that the United States has not been a country for that long). In "The Da Vinci Code," author Dan Brown caused great controversy when he put the number at 5 million, describing it as a relentless effort by the Roman Catholic Church to subjugate women. Far fewer died, but this was at a time when minuscule Europe was repopulating from cyclical scourges of the Black Death. We do know that two German towns slaughtered their women until only one per town remained.

How much time must elapse before these tortures ripen enough to be entertaining? Several summers ago at a carnival, I watched kids gleefully glide down an inflatable slide in the shape of the Titanic ... isn't that funny, kids? Ooh, they struggled to swim in water so cold it produced icebergs! In his novel "The Last Witchfinder," James Morrow mocks Salem's annual Haunted Happenings. This monthlong "festival" capitalizes on the famous witch trials where 19 people hanged, one suffocated by rocks piled on his chest and five perished in prison. Currently, the Haunted Happenings Web site promises "a month of fun for the entire family."

Today, parts of Africa still persecute witches, with attempted lynchings in Congo as recently as April 2008.

Last month, police fired shots into the air at a soccer game in eastern Congo, attempting to break up a melee of rioters who believed one of the players was a witch: 15 fans died from trampling. The latest trend is penis theft, where witches either steal outright, or render smaller, a male's member. Deja vu. The Malleus Maleficarum, the famous witch-hunting bible from 1400s Germany, spends an inordinate amount of print on this issue, concluding that the best remedy is to ask the witch to restore the phallus. And then, of course, burn her.

In the western world, we stuggle to imagine thinking someone could work evil spells or creep out at night to meet Satan. Harder still to imagine testifying about that spell-casting, knowing the result could be death. Instead of a stuffed, painted pillowcase, my neighbor down the block could've wanted me in her tree swinging.

So while spirits run high at Halloween -- actually one of my favorite holidays -- please consider those who were not of green tint, with wart-ridden noses, cackling maniacally while riding a broomstick straight into a tree (another "funny" decoration where the witch breaks her skull in an accident that would not be survivable if real) ... but who suffered incredibly for the same word: witch.

*Note: these dates are from October 2008. There have been many more recent occurrences of witchcraft persecutions and executions since then (including in February 2013, when a woman in Papua New Guinea was burned alive in front of hundreds who watched and jeered. If you are interested, please see the Labels archive on the righthand side; if you click on "Modern Day Witchcraft Persecutions" you will see posts where I covered media reports as they happened.

. . . .

Published on October 21, 2013 22:52

October 14, 2013

The Patty Reed Doll

My registration with the annual Donner Party Hike permitted me free entrance to the Emigrant Trail Museum. I think this was my third visit. Each time, I watch their half-hour video in the theater and each time I regret it. Why don't I learn?!

Seriously, although small, this is a fascinating collection. And there are dioramas, which I can never get enough of. History + Dollhouses = Diorama. Please don't get me started on the gigantic, ever-circling diorama at the O.K. Corral, narrated by Vincent Price. I hope it's still there.

Anyway, the museum displays a doll that apparently once claimed to be (well, the doll herself didn't claim; her humans did) the original one hidden by Patty Reed when her parents demanded they leave everything behind when they had to abandon the wagon(s).*

Let's back up. A few weeks prior, I visited Sutter's Fort. The true Patty Reed doll is on display there. I asked a docent if it was really was, because I knew there had been some controversy over the two museums' displaying of the doll. He rolled his eyes and diplomatically reported that there had been much trouble over the doll. Patty Reed left it to Sutter's Fort upon her death, in thanks for the free and generous care given to the emigrants when they finally made their way down to Sacramento--not to mention the fact that Sutter organized and funded the rescue parties--but apparently the museum at Donner Lake had it for a while and wanted to keep it. It's also traveled to Washington, D.C., to be exhibited at the Smithsonian.

This is from Gabrielle Burton's fine memoir, Searching for Tamsen Donner:

"A sign said that the original doll was on display at Sutter's Fort, but the ranger told me privately that over the years and the swapping back and forth, the original and the replica had gotten mixed up; no one knew anymore which museum had the original. I was appalled that even the experts didn't know, even more appalled when I got to Sutter's Fort and saw a shiny wooden copy of the doll that no one could possibly mix up with the weathered doll at Donner Pass. The ranger, training for his summer job, was passing on a good story, but not a true one."

I don't know much about object sharing between museums, but I believe a paper trail must accompany any shipment of an artifact. I don't buy the ranger's story that they got confused over the years--he makes it sound like they threw the doll in a cardboard box and sent it over the pass in a pickup truck. Also, possibly the two dolls have been switched since 2009 when Burton's book published, but I'd wager the Emigrant Trail Museum doll is the shiny one with overly-bright cheeks, and with a dress that looks like someone rubbed some dirt on it to make it look vintage. Who knows? I don't have an expert's eye and I believe that's why I was never asked back to be an evaluator on Antiques Roadshow. ;)

Judge for yourself. Below is the Emigrant Museum's doll in her fabricated snow habitat, and below that is the Sutter's Fort doll (supposedly the original).

I wish I had been able to obtain better images--you can google around and find excellent professional photographs. One last thought: the Sutter's Fort doll is certainly treated like she's the real deal. She's in an enclosed, temperature-controlled exhibit case (see below). The doll itself is surprisingly small, perhaps 3-4 inches.

*It's maybe just me, but I'm sure the parents knew. How can you not play with a doll you have when you're snowbound for four months, and how can your parents not notice? Perhaps they smiled privately and enjoyed letting her think she had gotten away with it. After all, in Ethan Rarick's book he closes with the lovely anecdote that after the rescue, Patty sat by the fire enacting the voices of the rescuers, using her doll. That shows that she played with the doll by voicing it--something she surely hadn't been able to suppress during the long entrapment. She was only eight, after all.

. . . . .

Published on October 14, 2013 21:34

October 10, 2013

The Donner Party encampment at Alder Creek

Last weekend I did the annual Donner Party hike, and wanted to talk briefly about the tent the George and Tamsen Donner family wintered in, 1846-47.

Here's the plaque that shows an artist's rendering of how they might have fashioned their shelter, by propping poles diagonally against an existing tree trunk, and covering it with the wagon canvas, branches and buffalo hides.

The only problem is, that structure simply isn't large enough. Into that space went George and Tamsen and their five children. Eliza Donner Houghton, three at the time, wrote in her book that sleeping platforms were built by driving poles straight into the ground and then lying branches horizontally: the depiction above would not permit such platforms. George Donner was an invalid from his hand-injury-turned-infection and surely had to lie down: a grown man takes quite a bit of space when resting on his back. Add in the fire--and the space around it which is too hot for human occupancy--and you've run out of room. Did the tent possibly completely encircle the tree?

I'm wondering if perhaps the poles were much longer and hit the tree further up, creating a wider, taller space. In one of the sources, I read that when visitors came--such as rescuer Clark, who spent two weeks with the Donners--there was not enough space for everyone unless if they laid in their beds. That says to me that besides the beds, there was open space.

There's also question about whether a teamster or two sheltered with them. One of the sources says that besides the nearby tent for the Jacob Donner family, there might have been a third structure for the teamsters. Given that they had tried first to construct a genuine cabin and abandoned the effort when it was four logs high, thanks to the fast-flying snow, it's hard to imagine that they bothered to make a third structure. But maybe they did...as we know, emotions were running high and maybe nuclear families wanted to withdraw and be with their own.

EITHER WAY, this was a terrible place to ride out the incredible storms of the Sierras. They couldn't have been very windproof, and they were soon covered with snow (like, completely buried in the snow, and they had to dig their way out to try to hunt or cut firewood): as the sun came out and warmed the snow, it would drip into their lodging. One source says Tamsen once despaired because her children had been wearing wet clothes for two weeks straight.

So, the tree itself...

There's a tree still extant that purports to be the exact tree the George Donner family built their structure against. This is it:

It's labeled with a sign from Peter Weddell, who says he was shown the tree by Charles McGlashan, the Truckee man who compiled survivor testimony in the first book about the Donner Party.

There are several problems with this identification. McGlashan had been unable to locate the site as late as 1879: after three decades in a woodland area with repeated snowfalls and melts, it might be pretty dicey to locate such a temporary shelter. Moreover, the area had been unceasingly picked by relic hunters and scavengers: both human and animal. The fourth relief--who brought out the sole survivor Lewis Keseberg-- reported that the Alder Creek encampment had clothing and property strewn across the snow: the camp's demise was coming as quickly as that of its unlucky inhabitants.

In 1884, McGlashan walked the Alder Creek area with Jean Baptiste Trudeau and still couldn't determine the precise spot for George's shelter. The same was true in 1892 when John Breen visited McGlashan.* Weddell may have misunderstood McGlashan.

Another key bit of data that had been forgotten and then rescusitated by Donner Party historian Kristin Johnson: the mention in Eliza's book that relief party men had cut down the tree their shelter rested against, for firewood. If so, there would be no tree to label and revere. This is problematic too: how could they remove the tree that everything rested upon, without the entire structure collapsing? Is it possible they cut the tree farther up, above the snow line and above where the supporting poles rested?

One of the frustrating things about this story is that much of the information is confusing or in some cases contradictory.

Meadow at Alder Creek

Meadow at Alder Creek

Guide Carrie Smith holds up a tiny piece of bone found at Alder Creek

Guide Carrie Smith holds up a tiny piece of bone found at Alder Creek

There has been a lot of archeology in the meadow. Our guides told us that a hearth was located: of course, nothing so blatant as a circle of stones, but instead an accumulation of orange dirt that indicated long-term fire that changed the composition of the soil (I'm only halfway through An Archeology of Desperation or I'd probably be able to write something smarter). Long-term fire is key: the Donners were here for four months, but many others have trooped through the area and built their fires. The discovery of the hearth almost certainly means one of the Donner sites was found: but which one? The site is not labeled and that's intentional. After a century and a half of people disturbing the site in their quest for Donner money or Donner relics, they want to protect it. An object, once taken from its original resting place, is of no use to an archeologist; it must remain in situ.

Sidenote: the guides told me of a similar situation, the nearby petroglyphs by the Washoe people. After a decision to plaque it and mark it for others, the holy site has been ravaged. "We have a sign saying please don't climb on the rock, and then I see 20 people up there," said one of the guides sadly.

So...the bones. They located thousands of fragments of cooked bone--and not one of them was human. That fact, when first released, caused a sort of hubbub where people jumped to the conclusion that cannibalism had not taken place at Alder Creek. The important distinction is that only cooked bone (and the guides talked about the "pot polish" on the bones, showing they had been boiled and stirred so much that they took on a surface from the metal pot) can survive. An uncooked bone--and anecdotal evidence seems to suggest that viscera were removed, and tissue cut from the bone, for consumption--would not have survived all these years.

My shadow: holding a bone fragment

My shadow: holding a bone fragment

There was a little Tupperware that went around our group, holding bone fragments and even a piece of clear bottle glass. So remarkable to hold these things!

Disclosure: not my hand

Disclosure: not my hand

Shoemaker's arm? No, just a branch

Shoemaker's arm? No, just a branch

*An Archeology of Desperation: Exploring the Donner Party's Alder Creek Camp, edited by Kelly J. Dixon, Julie M. Schablitsky and Shannon A. Novak. This very recent (2011) book was recommended to me by Kristin Johnson, and represents the latest knowledge about Alder Creek, fortified by the archeological digs performed there.

Here's the plaque that shows an artist's rendering of how they might have fashioned their shelter, by propping poles diagonally against an existing tree trunk, and covering it with the wagon canvas, branches and buffalo hides.

The only problem is, that structure simply isn't large enough. Into that space went George and Tamsen and their five children. Eliza Donner Houghton, three at the time, wrote in her book that sleeping platforms were built by driving poles straight into the ground and then lying branches horizontally: the depiction above would not permit such platforms. George Donner was an invalid from his hand-injury-turned-infection and surely had to lie down: a grown man takes quite a bit of space when resting on his back. Add in the fire--and the space around it which is too hot for human occupancy--and you've run out of room. Did the tent possibly completely encircle the tree?

I'm wondering if perhaps the poles were much longer and hit the tree further up, creating a wider, taller space. In one of the sources, I read that when visitors came--such as rescuer Clark, who spent two weeks with the Donners--there was not enough space for everyone unless if they laid in their beds. That says to me that besides the beds, there was open space.

There's also question about whether a teamster or two sheltered with them. One of the sources says that besides the nearby tent for the Jacob Donner family, there might have been a third structure for the teamsters. Given that they had tried first to construct a genuine cabin and abandoned the effort when it was four logs high, thanks to the fast-flying snow, it's hard to imagine that they bothered to make a third structure. But maybe they did...as we know, emotions were running high and maybe nuclear families wanted to withdraw and be with their own.

EITHER WAY, this was a terrible place to ride out the incredible storms of the Sierras. They couldn't have been very windproof, and they were soon covered with snow (like, completely buried in the snow, and they had to dig their way out to try to hunt or cut firewood): as the sun came out and warmed the snow, it would drip into their lodging. One source says Tamsen once despaired because her children had been wearing wet clothes for two weeks straight.

So, the tree itself...

There's a tree still extant that purports to be the exact tree the George Donner family built their structure against. This is it:

It's labeled with a sign from Peter Weddell, who says he was shown the tree by Charles McGlashan, the Truckee man who compiled survivor testimony in the first book about the Donner Party.

There are several problems with this identification. McGlashan had been unable to locate the site as late as 1879: after three decades in a woodland area with repeated snowfalls and melts, it might be pretty dicey to locate such a temporary shelter. Moreover, the area had been unceasingly picked by relic hunters and scavengers: both human and animal. The fourth relief--who brought out the sole survivor Lewis Keseberg-- reported that the Alder Creek encampment had clothing and property strewn across the snow: the camp's demise was coming as quickly as that of its unlucky inhabitants.

In 1884, McGlashan walked the Alder Creek area with Jean Baptiste Trudeau and still couldn't determine the precise spot for George's shelter. The same was true in 1892 when John Breen visited McGlashan.* Weddell may have misunderstood McGlashan.

Another key bit of data that had been forgotten and then rescusitated by Donner Party historian Kristin Johnson: the mention in Eliza's book that relief party men had cut down the tree their shelter rested against, for firewood. If so, there would be no tree to label and revere. This is problematic too: how could they remove the tree that everything rested upon, without the entire structure collapsing? Is it possible they cut the tree farther up, above the snow line and above where the supporting poles rested?

One of the frustrating things about this story is that much of the information is confusing or in some cases contradictory.

Meadow at Alder Creek

Meadow at Alder Creek Guide Carrie Smith holds up a tiny piece of bone found at Alder Creek

Guide Carrie Smith holds up a tiny piece of bone found at Alder CreekThere has been a lot of archeology in the meadow. Our guides told us that a hearth was located: of course, nothing so blatant as a circle of stones, but instead an accumulation of orange dirt that indicated long-term fire that changed the composition of the soil (I'm only halfway through An Archeology of Desperation or I'd probably be able to write something smarter). Long-term fire is key: the Donners were here for four months, but many others have trooped through the area and built their fires. The discovery of the hearth almost certainly means one of the Donner sites was found: but which one? The site is not labeled and that's intentional. After a century and a half of people disturbing the site in their quest for Donner money or Donner relics, they want to protect it. An object, once taken from its original resting place, is of no use to an archeologist; it must remain in situ.

Sidenote: the guides told me of a similar situation, the nearby petroglyphs by the Washoe people. After a decision to plaque it and mark it for others, the holy site has been ravaged. "We have a sign saying please don't climb on the rock, and then I see 20 people up there," said one of the guides sadly.

So...the bones. They located thousands of fragments of cooked bone--and not one of them was human. That fact, when first released, caused a sort of hubbub where people jumped to the conclusion that cannibalism had not taken place at Alder Creek. The important distinction is that only cooked bone (and the guides talked about the "pot polish" on the bones, showing they had been boiled and stirred so much that they took on a surface from the metal pot) can survive. An uncooked bone--and anecdotal evidence seems to suggest that viscera were removed, and tissue cut from the bone, for consumption--would not have survived all these years.

My shadow: holding a bone fragment

My shadow: holding a bone fragmentThere was a little Tupperware that went around our group, holding bone fragments and even a piece of clear bottle glass. So remarkable to hold these things!

Disclosure: not my hand

Disclosure: not my hand Shoemaker's arm? No, just a branch

Shoemaker's arm? No, just a branch*An Archeology of Desperation: Exploring the Donner Party's Alder Creek Camp, edited by Kelly J. Dixon, Julie M. Schablitsky and Shannon A. Novak. This very recent (2011) book was recommended to me by Kristin Johnson, and represents the latest knowledge about Alder Creek, fortified by the archeological digs performed there.

Published on October 10, 2013 11:27

October 8, 2013

Getting to the Donner Party Hike 2013

Last weekend, I returned to the annual Donner Party Hike which I last did many years ago, when we still lived in Oakland. This hike (which has now evolved into many different hike selections over two days, depending on your preferred level of strenuousness) follows part of the emigrants’ trail. I remember last time spending all day hiking to sites where the guides pointed out scars on tree trunks, from where the wagons scraped through, and where we saw the infamous Roller Pass.

Our group: there were maybe 25 of us

Our group: there were maybe 25 of usThis year I chose to do the hike (maybe more like a tour--not much walking involved) that focused on Alder Creek, the separate encampment area seven miles from Donner Lake, where the two Donner families and a few others set up their fragile domiciles to wait out the winter of 1846-47.

Tree long thought to be where Tamsen and family built shelter against

Tree long thought to be where Tamsen and family built shelter againstI was obliged to leave the house at 6:45 a.m. in order to get there in time. Just like the Donners leaving Springfield, Missouri, I got a bit of a late start. My delay was only 10 minutes, but still…

Barely a mile from my house, I looked down at my gas gauge. I had a third of a tank. Definitely enough to make it there, but maybe not enough to make it back? I reasoned I could fill up on the return trip, but maybe I’d be rushing even more then, so I stopped to fill up my tank. This might be akin to the Donners during one of their many time-killers: maybe the reason they were so late starting on the trail was that they stopped for the equivalent of gas. Remember Tamzene wrote that, “Indeed, if I do not experience something far worse than I have yet done, I shall say the trouble is all in getting started.”

Plaque: how the shelter may have been constructed against tree trunk

Plaque: how the shelter may have been constructed against tree trunkNow, you’ll think I’m making this up for purposes of parallelism, but as I drove along I began to feel excruciatingly hungry. I had left the house without breakfast because of the early hour, reasoning I’d grab coffee and something quick along the way. But I was really, really hungry. I let the feeling sit for a while, thinking it was good practice to imagine how the Donners felt this way for months on end. Ultimately, I had to stop. I was trying for a breakfast burrito, but driving around the strip mall I couldn’t locate the intended purveyor, so instead I went to a donut shop in that outlet. I picked a cake donut, thinking it looked a little healthier than its fluffier peers (I got it chocolate frosted; I’m not a martyr), and some decaf coffee and was back on the road.

Close-up of tree: aging Peter Weddell sign and Earl Rhoads blazeI made good time, but my “Wasatch Mountains/Great Salt Desert” was the fact that I couldn’t determine the proper exit off the highway. I got off and suddenly somehow thanks to a roundabout found myself back on it. I drove, I looked at the time, I started to panic. I pulled into a ranger station and got some good advice, unlike the Donners. I made it to the hike rendez-vous with 15 minutes to spare.

Close-up of tree: aging Peter Weddell sign and Earl Rhoads blazeI made good time, but my “Wasatch Mountains/Great Salt Desert” was the fact that I couldn’t determine the proper exit off the highway. I got off and suddenly somehow thanks to a roundabout found myself back on it. I drove, I looked at the time, I started to panic. I pulled into a ranger station and got some good advice, unlike the Donners. I made it to the hike rendez-vous with 15 minutes to spare.At their registration table ("Johnson Ranch")? Coffee and donuts. Ha!

Their restroom was completely locked up thanks to the government shutdown. I had to walk into the woods and wonder if I was watering the same soil the Donners had.

Where I guiltily ate almonds. Excellent guides: Carrie Smith, left, and Gayle Green

Where I guiltily ate almonds. Excellent guides: Carrie Smith, left, and Gayle GreenAnd there the coincidences stop. I was not entrapped at Alder Creek. Snow did not fall. No one’s hand was injured. Buffalo hides were not eaten, nor were shoestrings nor fire rugs. I had brought a little sack lunch in my backpack that satisfied. I did feel like a turncoat standing there at the tree once thought to be the one the George Donner family had built their structure against, munching on a handful of almonds. If I could’ve slipped that food back in time, believe me, I would have.

This young tree was planted by Donner descendantsThis story pulls at my gut, has me obsessively reading three books at a time on the topic, carrying on a wonderful email correspondence with a highly-regarded Donner Party historian, and even giving my poor community college students writing assignments like, “Write a letter to Lansford Hastings, pretending you’re a survivor.”

This young tree was planted by Donner descendantsThis story pulls at my gut, has me obsessively reading three books at a time on the topic, carrying on a wonderful email correspondence with a highly-regarded Donner Party historian, and even giving my poor community college students writing assignments like, “Write a letter to Lansford Hastings, pretending you’re a survivor.”Not too long ago, I told my husband a particularly disturbing anecdote from the Donner Party annals—not about cannibalism; oddly enough, I don’t find that aspect that compelling or interesting—and he said, “That’s why you can’t sleep at night. You read this stuff right before you go to bed.” He was, well, suggesting I stop doing so. It was a gentle suggestion on his part, so I didn't say what I thought, which was, “If you want me to stop reading about the Donner Party, then you married the wrong woman!”

He just wants me to sleep soundly. In our warm bed, where we can hardly even hear the wind blow outside, where a few rooms away cupboards await us, filled with food.

. . . . .

Published on October 08, 2013 22:34

The serendipity behind The Witch's Trinity

At the Historical Novels Society, I met a wonderful fellow writer, Stephanie Renee Dos Santos. Recently, she approached me because she was writing a series of articles on serendipity in fiction. She had looked at my website and learned that I had not known about my witchcraft ancestor, Mary Bliss Parsons, until after I was already underway with my novel about witchcraft, The Witch's Trinity. That counts as an item of uncanny serendipity, and so she included me in her series--which I think is extraordinary. Although I'll link to my post in the series, I highly recommend all of them! They are available through the Historical Novels Society website, here.

Enough time has elapsed that I think it's okay to go ahead and re-post here. Thanks again to Stephanie for including me in the series.

Stories of Serendipity: Writing Historical Fiction Series Featuring author Erika MailmanStephanie Renee dos Santos

Welcome to the third week of our series where writers share stories of serendipity and synchronicity while writing, researching and publishing historical fiction, and the exploration of possible reasons for such occurrences.

This Sunday we are delving into the world of the female shaman: amulets, witches, magic.

Come read on…

Muiraquita amulet

My final tale to impart for the series has to do with an Amazon talisman: a green frog amulet. The last third of my novel, Cut From the Earth (working title), takes place in the Brazilian Amazon in 1756, at a time when Catholic missions of multiple sects proselytized along the immense river and her tributaries. Writing my book’s first draft, I had given a fictional female shaman character a lichen-colored stone necklace in the shape of a frog and located the scene of her appearance in the Tapajos River region of the Amazon, at the historically documented Jesuit Mission of Tapajos– all things, but the mission, I thought I’d made up. But after completing my novel’s first draft, I flew to the great river mouth of the Amazon, to the town of Belém, to travel the river section of my book, to take in the surroundings and further investigate the places of my story. And while in Belém I came across a museum I hadn’t read about in any literature prior to my trip. While visiting the museum’s displays, I came across a story that explained that the indigenous women of the Tapajos River were known to possess jade-colored, frog-shaped stone pendants called a muiraquitã and that the gemstone it was made out of, nephrite, was found only in the Tapajos region of the Amazon. Bewildered, dumbfounded, I stared at the physical example of the amulet of my character in the showcase and read about her, gaining more insight into the powers associated with the real life revered stone and its holders.

It is my pleasure to hand you over to Erika Mailman, author of The Witch’s Trinity, and her uncanny and bewitching story of serendipity and coincidence…

“My novel The Witch’s Trinity was well underway when I got an odd email from my mother. “We’re related to a witch!” she reported. I was stunned. All my life I’d been fascinated by witchcraft, and had even pretended that a particular name on the family tree that hung in the stairwell was the dark mistress in question. My mother had learned about Mary Bliss Parsons, our ancestor, via a friend who sent a link to an extraordinary website UMass website which contains testimony—both typed and scanned-in originals—from Mary’s neighbors, condemning and protecting her. Mary was accused of myriad crimes, such as going into the river and coming out dry, and causing a farmer’s sow to die when formerly she was a “lusty swine and well fleshed.” She dispatched a rattlesnake to bite an ox, made a young boy trip in the woods and hurt his knee, and made spun yarn diminish in volume after it had been sold. That’s just a minor catalogue of her doings.

Calling down the rain”: in the 1489 edition of De Lamiis, witches create

a brew to bring down the rain.

Two things were extraordinary to me. The first was that I had never heard of Mary Bliss Parsons before, and we were a family that was very proud of our heritage…including Mary’s husband Cornet Joseph Parsons, a founding father of Northampton, Massachusetts, where Smith College is today. We knew all about his life, but not one word about his wife’s witchcraft accusations—yes, plural, because 18 years after she was acquitted from her first trial, she was accused again. There’s even some evidence she may have faced a third accusation, but she died under the label “innocent” as an old woman, aged 85. Why was her story suppressed in the oral pass-down of our family history? And why would I learn about it while I was in the middle of writing a novel about witchcraft?

The other extraordinary thing to me was that I learned about my own ancestor through an educational website. I shiver to think of how our technology would appear to the people of 1656, the year of Mary’s first witchcraft trial. The testimony, handwritten by the court’s recorder, has now been scanned in and we can examine his every quillstroke. How is it possible that the deeds of a town consisting of only 47 households—Springfield, Massachusetts—are now freely available to a world of 7 billion people? As she died, she must’ve thought the rumors and tensions would die with her. Instead, they have been resuscitated and revived for a new audience. That is its own kind of witchery.

I’m at a loss how to explain such a coincidence. I kept using the word “uncanny” at the time (which Merriam-Webster asserts means “seeming to have a supernatural character or origin”). I wrote The Witch’s Trinity in nine months; how unusual that after decades of not knowing about my ancestor, I learned about her in this very narrow window of time when I was focused on the unfair and cruel situation she faced?

My editor asked me to write a brief essay about Mary Bliss Parsons, and it is included in my

novel’s Afterword. I appreciated the official request to learn more about my ancestor. It was sobering to learn that she was outspoken and freely dispensed advice, and that probably spelled her downfall. For instance, she scolded a neighbor for whipping borrowed oxen so hard—surely not a woman’s purview—and he accused her of causing his own ox to die. She was said to be “a proud and nervous woman, haughty in demeanor and inclined to carry things with a high hand”: in short, a woman who was confident and didn’t meekly bow her head as the culture then expected. I’d like to think my book is a form of apologia for Mary. She would doubtless fit into today’s world far better, and it’s sad that her era did not support her strength.”

. . . .

Enough time has elapsed that I think it's okay to go ahead and re-post here. Thanks again to Stephanie for including me in the series.

Stories of Serendipity: Writing Historical Fiction Series Featuring author Erika MailmanStephanie Renee dos Santos

Welcome to the third week of our series where writers share stories of serendipity and synchronicity while writing, researching and publishing historical fiction, and the exploration of possible reasons for such occurrences.

This Sunday we are delving into the world of the female shaman: amulets, witches, magic.

Come read on…

Muiraquita amulet

My final tale to impart for the series has to do with an Amazon talisman: a green frog amulet. The last third of my novel, Cut From the Earth (working title), takes place in the Brazilian Amazon in 1756, at a time when Catholic missions of multiple sects proselytized along the immense river and her tributaries. Writing my book’s first draft, I had given a fictional female shaman character a lichen-colored stone necklace in the shape of a frog and located the scene of her appearance in the Tapajos River region of the Amazon, at the historically documented Jesuit Mission of Tapajos– all things, but the mission, I thought I’d made up. But after completing my novel’s first draft, I flew to the great river mouth of the Amazon, to the town of Belém, to travel the river section of my book, to take in the surroundings and further investigate the places of my story. And while in Belém I came across a museum I hadn’t read about in any literature prior to my trip. While visiting the museum’s displays, I came across a story that explained that the indigenous women of the Tapajos River were known to possess jade-colored, frog-shaped stone pendants called a muiraquitã and that the gemstone it was made out of, nephrite, was found only in the Tapajos region of the Amazon. Bewildered, dumbfounded, I stared at the physical example of the amulet of my character in the showcase and read about her, gaining more insight into the powers associated with the real life revered stone and its holders.

It is my pleasure to hand you over to Erika Mailman, author of The Witch’s Trinity, and her uncanny and bewitching story of serendipity and coincidence…

“My novel The Witch’s Trinity was well underway when I got an odd email from my mother. “We’re related to a witch!” she reported. I was stunned. All my life I’d been fascinated by witchcraft, and had even pretended that a particular name on the family tree that hung in the stairwell was the dark mistress in question. My mother had learned about Mary Bliss Parsons, our ancestor, via a friend who sent a link to an extraordinary website UMass website which contains testimony—both typed and scanned-in originals—from Mary’s neighbors, condemning and protecting her. Mary was accused of myriad crimes, such as going into the river and coming out dry, and causing a farmer’s sow to die when formerly she was a “lusty swine and well fleshed.” She dispatched a rattlesnake to bite an ox, made a young boy trip in the woods and hurt his knee, and made spun yarn diminish in volume after it had been sold. That’s just a minor catalogue of her doings.

Calling down the rain”: in the 1489 edition of De Lamiis, witches create

a brew to bring down the rain.

Two things were extraordinary to me. The first was that I had never heard of Mary Bliss Parsons before, and we were a family that was very proud of our heritage…including Mary’s husband Cornet Joseph Parsons, a founding father of Northampton, Massachusetts, where Smith College is today. We knew all about his life, but not one word about his wife’s witchcraft accusations—yes, plural, because 18 years after she was acquitted from her first trial, she was accused again. There’s even some evidence she may have faced a third accusation, but she died under the label “innocent” as an old woman, aged 85. Why was her story suppressed in the oral pass-down of our family history? And why would I learn about it while I was in the middle of writing a novel about witchcraft?

The other extraordinary thing to me was that I learned about my own ancestor through an educational website. I shiver to think of how our technology would appear to the people of 1656, the year of Mary’s first witchcraft trial. The testimony, handwritten by the court’s recorder, has now been scanned in and we can examine his every quillstroke. How is it possible that the deeds of a town consisting of only 47 households—Springfield, Massachusetts—are now freely available to a world of 7 billion people? As she died, she must’ve thought the rumors and tensions would die with her. Instead, they have been resuscitated and revived for a new audience. That is its own kind of witchery.

I’m at a loss how to explain such a coincidence. I kept using the word “uncanny” at the time (which Merriam-Webster asserts means “seeming to have a supernatural character or origin”). I wrote The Witch’s Trinity in nine months; how unusual that after decades of not knowing about my ancestor, I learned about her in this very narrow window of time when I was focused on the unfair and cruel situation she faced?

My editor asked me to write a brief essay about Mary Bliss Parsons, and it is included in my

novel’s Afterword. I appreciated the official request to learn more about my ancestor. It was sobering to learn that she was outspoken and freely dispensed advice, and that probably spelled her downfall. For instance, she scolded a neighbor for whipping borrowed oxen so hard—surely not a woman’s purview—and he accused her of causing his own ox to die. She was said to be “a proud and nervous woman, haughty in demeanor and inclined to carry things with a high hand”: in short, a woman who was confident and didn’t meekly bow her head as the culture then expected. I’d like to think my book is a form of apologia for Mary. She would doubtless fit into today’s world far better, and it’s sad that her era did not support her strength.”

. . . .

Published on October 08, 2013 14:44