Elizabeth Sherrill's Blog

May 29, 2023

ELIZABETH "TIB" SHERRILL OBITUARY

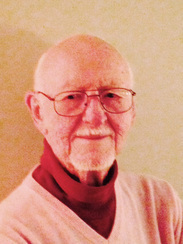

Elizabeth (“Tib”) Sherrill died peacefully on Saturday, May 20, 2023 in Hingham, Ma. at the age of 95.

Elizabeth (“Tib”) Sherrill died peacefully on Saturday, May 20, 2023 in Hingham, Ma. at the age of 95. She was a beloved author and speaker, writing inspirational true stories about people overcoming hardship through their faith. She published over 2000 articles and authored more than 30 books, including The Hiding Place, The Cross and the Switchblade, God’s Smuggler and They Speak With Other Tongues. Tib was a writer and editor for Guideposts Magazine for over 65 years and ran many of their Writer’s Workshops. In 1970, she and her late husband John founded Chosen Books, a publishing company dedicated to developing new Christian writers.

Tib and John, who died in 2017, worked as a writing and editing team. With their three children, the Sherrill’s spent a year as roving editors in Africa and another year in South America. They lived in England for a year and made numerous trips to the Near and Far East, as well as all 50 United States. In 2009, they moved from their home of 50 years in Chappaqua, New York, to Hingham, Ma.

Tib and John were married for 70 years. They met aboard the Queen Elizabeth en route to Europe in 1947 and were married three months later in Switzerland.

Tib was born February 14, 1928 in Los Angeles, CA. and grew up in Scarsdale, N.Y. She leaves a sister, Caroline Strout of Needham, Ma., and a brother, Donn Schindler, of St.Croix, VI. She leaves her three children: John Scott Sherrill of Nashville, Tennessee, Donn Hardwick Sherrill of Miami, Fl. and Elizabeth (Liz) Flint of Hingham, Ma., eight grandchildren: Kerlin Richter (Portland, Or.), Lindsay Hooten (Alpharetta, Ga.),Andrew Sherrill (Decatur, Ga.), Daniel Sherrill (Orlando, Fl.), Jeffery Flint (Hingham, Ma.). Sarah Flint (Pembroke, Ma.), Peter Sherrill (Nashville, Tn.), Spencer Sherrill (Nashville, Tn.), and seven great-grandchildren.

A Celebration of Life will be held at St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church, 172 Main St., Hingham, Ma. At 10:00 am on Saturday, June 3, 2023. All relatives and friends are invited to attend.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to:

St. John the Evangelist Church

172 Main St., Hingham, Ma. 02043

Published on May 29, 2023 13:51

March 7, 2018

Coming to the Table

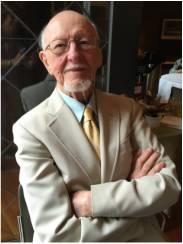

On December 2, 2017, I lost my beloved husband of 70 years. John was 94. He spent his final months with hospice care here in our apartment.

On December 2, 2017, I lost my beloved husband of 70 years. John was 94. He spent his final months with hospice care here in our apartment. In a snowstorm a week after his death, an overflow crowd of friends and family gathered at our church, St. John the Evangelist in Hingham, Massachusetts, for his funeral. Before the congregation went forward for the Eucharist (Communion, Lord’s Table) our granddaughter, Kerlin Richter, an Episcopal priest from Portland, Oregon, had this to say…

I have been asked this afternoon to do an impossible thing. I have been asked to say a few words about my grandfather, the man I called Papa John. A thousand words come to mind just with those two words. Everyone here has a thousand stories about him. They will tell you of his boundless curiosity, and his nearly pathological outgoing-ness, his ability to meet strangers and within seconds become friends. Papa John was able to see people with a clarity and compassion that was nothing short of holy.

As frequent as the people stories are the food stories, the meal preparation stories, the restaurant enthusiasms. He cooked and ate the way he saw people, eagerly and with his whole heart.

In his final years he became fascinated with the Eucharist, that place where prayer and dinner intersect. The Jesus we love was as fond of eating with friends as Papa John was. One day, during one of our “feet up” chats over the phone, I shared with him my favorite Eucharistic theology which I learned from an old Lakota priest one summer in South Dakota. Fr. Noisy Hawk said that the Eucharist is one eternal moment. The bread is only ever broken once. The cup is lifted up once. And every time we do this we are in that one moment. And there at the table with us in that moment is everyone who has ever held out their hands reaching for a taste of love.

Now again I am heading to that table. For a mystical feast where my grandfather and I and all of us here will eat together. Where we already are eating together as we always have been and always will be. And by the light of the love of God, we will see each other.

And so the last of my “few words” will be just these: “I miss you. I love you. I will see you in a few minutes at the table.”

Published on March 07, 2018 16:01

December 17, 2014

The Secret

Below, the text of John's story as recently published and copyrighted 2014 by Guideposts Magazine. All rights reserved.

Below, the text of John's story as recently published and copyrighted 2014 by Guideposts Magazine. All rights reserved.This Returning Vet came home 70 years ago. For the first time, with this story, he talks about his World War II experiences.

“Take cover!” The mortars began exploding seconds after the sergeant’s shout. Thunderclaps straight overhead. I ran with the rest of the platoon. Nearest foxhole -- that was the order in a mortar attack. We’d dug some 30 of these little slit trenches earlier in the day but in

the near-dark, shrapnel blasting everywhere, they were hard to spot. I saw one and dove for it, arms flailing. There was a cry of pain.

“John! John, wake up!”`

I blinked in the sudden glare of the lamp at our bedside. My wife Tib was clutching her ear. “You hit me!”

I stared at her, at the dresser, the wallpaper.

“Was it the same dream?” she said,

I nodded, part of me still back on that hillside in Italy.

“Can you talk about it?”

I shook my head. WWII was long over and yet, I thought, as I made a cold compress for Tib’s scarlet ear, the guilt over that night was as sharp as ever.

Actually, the guilt began before I reached Italy. I hadn’t waited for the draft. If you volunteered for the Army out of college, the promotional flyer went, you’d be sent to officers’ training. But I’d barely signed the enlistment papers before orders changed. Soon I found myself on a sooty, jam-packed troop train headed for basic training in the 110-degree heat of Camp Wolters, Texas. Three months later, with hundreds of other newly-graduated privates, I disembarked from a troop ship in Algeria, assigned to the Repple Depple in Oran.

Repple Depple?

Army slang, someone explained, for Replacement Depot. “Guess we’re headed for Italy.” Back in Texas we’d watched news reels of the amphibious landings on the Italian coast. These were “great victories,” of course, as were all reported battles in 1943, but apparently the successes had been bought at a staggering cost in lives. Replacements for these lost men, I realized, that’s what we green, hastily-trained kids were. I began the slow trek up the boot of Italy walking in dead men’s shoes.

At first we traveled in open trucks, strangers, facing each other with our M1 rifles between our legs. During basic training, and on the troop ship, I’d made friends, but we were separated, split up, assigned to fill out the ranks of decimated units. In front of me were battle-toughened soldiers returning to the front from rest-and-recuperation leave.

As we got closer to the combat zone, it was out of the truck and onto paths with 30-lb-plus packs on our backs. At the end of a day we’d bivouac in an open field or an abandoned farm, once outside a deserted, still smoking village. Occasionally we passed bodies. A German soldier stripped of coat and shoes. A blue-clad old man beside a dead donkey.

We seldom knew where we were. With road signs removed and town names painted over, we knew only that we were in rocky hill country somewhere south of Rome, and that the sound of artillery fire was getting closer. One morning our lieutenant assigned four of us to a reconnaissance patrol. An hour later we rounded a boulder and almost bumped into a Panzer. As the tank’s turret swung toward us we discovered undreamed-of skills of dodge-and-evade.

Foxholes became harder to dig as the paths became steeper, the ground stonier. “Keep digging, soldier!” the sergeant would bellow each time I slowed down. Once in a while one of the veterans would offer a bit of advice. “Never go into a field where you see onions. Jerry mines those.” “Mortar attack,” another old-timer advised as our shovels hacked at the scrabble on a hillside, “that’s the worst.” They were timed to explode at head-height, he explained, jagged shards of hot metal flying in every direction. “That’s when you’ll need a hole – any hole -- in a hurry.”

A hole! Any hole! It was the only thought in my head, the night the mortars hit. The night that would replay in my dreams forever after. With shrapnel thudding all around, I dove into the first foxhole I saw and flattened myself against the stones, jamming my fingers in my ears against the roar of what seemed one endless explosion.

Next instant the breath was knocked out of me as something landed on my back. The weight crushed me against the earth, rocks stabbing my chest.

It was a second before I realized that another soldier had dived into the foxhole on top of me. I struggled to breathe, spitting dirt from my mouth, as we cowered together in that shallow pit with the sky exploding above us.

Then there was a scream. “I’m hit! O God!”

The body above me was jerking. “O my God!” he screamed again. “O God!” Something wet and warm was soaking into the back of my shirt. The boy above me stopped shouting. My shirt got wetter.

It was a million years before the shelling stopped. The body pressing on mine didn’t move. I tried shouting “Medic!” and got a mouthful of dirt. For a long time it was totally dark. No movement, no sound above me. Then on the rim of the foxhole I saw moving lights, flashlighted medics coming close.

The weight on me lifted. A voice. “Are you hurt bad, soldier?”

“I’m okay,” I managed to get out. “The other guy. He was hit.”

“We got him. He didn’t make it.” I felt my shirt pulled up, fingers probing, voices conferring. “Looks like it’s the other guy’s blood.”

The other guy’s blood… The guy who took a hunk of shrapnel instead of me. By the time I got to my knees and looked around in the bobbing lights, they’d taken him away. I never saw his face, never knew his name. But since that night he’s never left my side.

There were other deaths. Three times -- perhaps because I could type -- I was asked to inventory the gear of some guy who was going home in a coffin. With every form I filled in, the question grew more acute. Why him? Why not me?

The closest I came to dying myself was not enemy fire but illness.

One day, instead of moving forward, we were herded into a field hospital for hypodermic shots. “What’s it for?” I asked. “Roll up your sleeve, soldier.” Two days later I was running a fever. In tents all around men were moaning and vomiting. It seemed our entire company was sick – high fever, chills, headache, eyes and skin strangely yellow. The deadly outbreak of hepatitis was eventually traced to a contaminated batch of Yellow Fever vaccine, given in anticipation of the European war ending and transfer to the Pacific.

They ambulanced us to the U.S. military hospital just outside Naples. And there again I watched others die. The guy on the cot next to mine. Another two cots away. Every morning, empty cots. Why them and not me?

It’s a question asked by combat veterans after every war. It even has a name. Survivor Guilt. Some ex-soldiers handle it by grouping together for support with other vets. Some handle it through their faith, but at that point I had none. I dealt with survivor guilt by clamming up. Willing none of it to have happened. Refusing to talk because that would make it real.

It doesn’t work, of course, silence. No one guessed my secret turmoil because in most ways my life was rich and full. Tib and I had a great marriage, children and grandchildren, rewarding jobs at Guideposts where we met hundreds of inspiring people and helped them tell their stories. In time we found our own church home; faith became the center of our lives.

And even with all this, the nightmare kept recurring. And with it, the question that haunts veterans of every war. Why not me? Every wedding Tib and I attended. Every baptism at our church. Every time I held a grandchild in my arms. The boy in my foxhole never held a grandchild.

One day in the spring of 1989 when Tib and I were on living in Normandy, our daughter, her husband and their 10-month-old came to visit. Our son-in-law was eager to visit the American Cemetery, so the four of us walked, little Jeffrey on his daddy’s back, along those long, long rows of white crosses and Stars of David stretching out of sight. The others went ahead, but I stopped before grave marker after grave marker: 1923-1945, 1923-1945, 1923-1945… Again and again, my birth year over the body of a 22-year-old who could have been – should have been? – me.

Twenty-five years later, when Guideposts asked me if I had anything to say to today’s returning soldiers, I discovered to my surprise that I did in fact have something to say to all of us who come home with memories we cannot talk about. Because we have another kind of secret, too. We have a window into the unspoken pain of others.

A simple example occurred back there in the American Cemetery. A few rows away I noticed a man, maybe in his mid-40s, standing alone like me, staring at a grave marker. I strolled over to him, asked him for the time, and we started chatting. Suddenly he began to cry. “I never knew my dad,” he said. At once our conversation became personal. But from the start, with my question about the time, I was praying. Not with words but with caring and listening. We kept in touch for years.

Ever since the war it’s as if I had a second set of eyes. I can spot a lonely person a mile away. Someone grieving at a grave site is obvious, but I can see through the heartiest, most glad-handed, all-smiles guy or gal in the room. When I’m granted this kind of vision, I wait, and if God opens a door, I step through. It’s led to some amazing, always private, friendships over the years.

That’s what I have to say to today’s returning vets: we have work to do. And the wonder, for us war-scarred types, is that it happens not in spite of the pain, but because of it.

Published on December 17, 2014 20:36

The Secret

Below, the text of John's story as recently published and copyrighted 2014 by Guideposts Magazine. All rights reserved.

Below, the text of John's story as recently published and copyrighted 2014 by Guideposts Magazine. All rights reserved.This Returning Vet came home 70 years ago. For the first time, with this story, he talks about his World War II experiences.

“Take cover!” The mortars began exploding seconds after the sergeant’s shout. Thunderclaps straight overhead. I ran with the rest of the platoon. Nearest foxhole -- that was the order in a mortar attack. We’d dug some 30 of these little slit trenches earlier in the day but in the near-dark,

shrapnel blasting everywhere, they were hard to spot. I saw one and dove for it, arms flailing. There was a cry of pain.

“John! John, wake up!”`

I blinked in the sudden glare of the lamp at our bedside. My wife Tib was clutching her ear. “You hit me!”

I stared at her, at the dresser, the wallpaper.

“Was it the same dream?” she said,

I nodded, part of me still back on that hillside in Italy.

“Can you talk about it?”

I shook my head. WWII was long over and yet, I thought, as I made a cold compress for Tib’s scarlet ear, the guilt over that night was as sharp as ever.

Actually, the guilt began before I reached Italy. I hadn’t waited for the draft. If you volunteered for the Army out of college, the promotional flyer went, you’d be sent to officers’ training. But I’d barely signed the enlistment papers before orders changed. Soon I found myself on a sooty, jam-packed troop train headed for basic training in the 110-degree heat of Camp Wolters, Texas. Three months later, with hundreds of other newly-graduated privates, I disembarked from a troop ship in Algeria, assigned to the Repple Depple in Oran.

Repple Depple?

Army slang, someone explained, for Replacement Depot. “Guess we’re headed for Italy.” Back in Texas we’d watched news reels of the amphibious landings on the Italian coast. These were “great victories,” of course, as were all reported battles in 1943, but apparently the successes had been bought at a staggering cost in lives. Replacements for these lost men, I realized, that’s what we green, hastily-trained kids were. I began the slow trek up the boot of Italy walking in dead men’s shoes.

At first we traveled in open trucks, strangers, facing each other with our M1 rifles between our legs. During basic training, and on the troop ship, I’d made friends, but we were separated, split up, assigned to fill out the ranks of decimated units. In front of me were battle-toughened soldiers returning to the front from rest-and-recuperation leave.

As we got closer to the combat zone, it was out of the truck and onto paths with 30-lb-plus packs on our backs. At the end of a day we’d bivouac in an open field or an abandoned farm, once outside a deserted, still smoking village. Occasionally we passed bodies. A German soldier stripped of coat and shoes. A blue-clad old man beside a dead donkey.

We seldom knew where we were. With road signs removed and town names painted over, we knew only that we were in rocky hill country somewhere south of Rome, and that the sound of artillery fire was getting closer. One morning our lieutenant assigned four of us to a reconnaissance patrol. An hour later we rounded a boulder and almost bumped into a Panzer. As the tank’s turret swung toward us we discovered undreamed-of skills of dodge-and-evade.

Foxholes became harder to dig as the paths became steeper, the ground stonier. “Keep digging, soldier!” the sergeant would bellow each time I slowed down. Once in a while one of the veterans would offer a bit of advice. “Never go into a field where you see onions. Jerry mines those.” “Mortar attack,” another old-timer advised as our shovels hacked at the scrabble on a hillside, “that’s the worst.” They were timed to explode at head-height, he explained, jagged shards of hot metal flying in every direction. “That’s when you’ll need a hole – any hole -- in a hurry.”

A hole! Any hole! It was the only thought in my head, the night the mortars hit. The night that would replay in my dreams forever after. With shrapnel thudding all around, I dove into the first foxhole I saw and flattened myself against the stones, jamming my fingers in my ears against the roar of what seemed one endless explosion.

Next instant the breath was knocked out of me as something landed on my back. The weight crushed me against the earth, rocks stabbing my chest.

It was a second before I realized that another soldier had dived into the foxhole on top of me. I struggled to breathe, spitting dirt from my mouth, as we cowered together in that shallow pit with the sky exploding above us.

Then there was a scream. “I’m hit! O God!”

The body above me was jerking. “O my God!” he screamed again. “O God!” Something wet and warm was soaking into the back of my shirt. The boy above me stopped shouting. My shirt got wetter.

It was a million years before the shelling stopped. The body pressing on mine didn’t move. I tried shouting “Medic!” and got a mouthful of dirt. For a long time it was totally dark. No movement, no sound above me. Then on the rim of the foxhole I saw moving lights, flashlighted medics coming close.

The weight on me lifted. A voice. “Are you hurt bad, soldier?”

“I’m okay,” I managed to get out. “The other guy. He was hit.”

“We got him. He didn’t make it.” I felt my shirt pulled up, fingers probing, voices conferring. “Looks like it’s the other guy’s blood.”

The other guy’s blood… The guy who took a hunk of shrapnel instead of me. By the time I got to my knees and looked around in the bobbing lights, they’d taken him away. I never saw his face, never knew his name. But since that night he’s never left my side.

There were other deaths. Three times -- perhaps because I could type -- I was asked to inventory the gear of some guy who was going home in a coffin. With every form I filled in, the question grew more acute. Why him? Why not me?

The closest I came to dying myself was not enemy fire but illness.

One day, instead of moving forward, we were herded into a field hospital for hypodermic shots. “What’s it for?” I asked. “Roll up your sleeve, soldier.” Two days later I was running a fever. In tents all around men were moaning and vomiting. It seemed our entire company was sick – high fever, chills, headache, eyes and skin strangely yellow. The deadly outbreak of hepatitis was eventually traced to a contaminated batch of Yellow Fever vaccine, given in anticipation of the European war ending and transfer to the Pacific.

They ambulanced us to the U.S. military hospital just outside Naples. And there again I watched others die. The guy on the cot next to mine. Another two cots away. Every morning, empty cots. Why them and not me?

It’s a question asked by combat veterans after every war. It even has a name. Survivor Guilt. Some ex-soldiers handle it by grouping together for support with other vets. Some handle it through their faith, but at that point I had none. I dealt with survivor guilt by clamming up. Willing none of it to have happened. Refusing to talk because that would make it real.

It doesn’t work, of course, silence. No one guessed my secret turmoil because in most ways my life was rich and full. Tib and I had a great marriage, children and grandchildren, rewarding jobs at Guideposts where we met hundreds of inspiring people and helped them tell their stories. In time we found our own church home; faith became the center of our lives.

And even with all this, the nightmare kept recurring. And with it, the question that haunts veterans of every war. Why not me? Every wedding Tib and I attended. Every baptism at our church. Every time I held a grandchild in my arms. The boy in my foxhole never held a grandchild.

One day in the spring of 1989 when Tib and I were on living in Normandy, our daughter, her husband and their 10-month-old came to visit. Our son-in-law was eager to visit the American Cemetery, so the four of us walked, little Jeffrey on his daddy’s back, along those long, long rows of white crosses and Stars of David stretching out of sight. The others went ahead, but I stopped before grave marker after grave marker: 1923-1945, 1923-1945, 1923-1945… Again and again, my birth year over the body of a 22-year-old who could have been – should have been? – me.

Twenty-five years later, when Guideposts asked me if I had anything to say to today’s returning soldiers, I discovered to my surprise that I did in fact have something to say to all of us who come home with memories we cannot talk about. Because we have another kind of secret, too. We have a window into the unspoken pain of others.

A simple example occurred back there in the American Cemetery. A few rows away I noticed a man, maybe in his mid-40s, standing alone like me, staring at a grave marker. I strolled over to him, asked him for the time, and we started chatting. Suddenly he began to cry. “I never knew my dad,” he said. At once our conversation became personal. But from the start, with my question about the time, I was praying. Not with words but with caring and listening. We kept in touch for years.

Ever since the war it’s as if I had a second set of eyes. I can spot a lonely person a mile away. Someone grieving at a grave site is obvious, but I can see through the heartiest, most glad-handed, all-smiles guy or gal in the room. When I’m granted this kind of vision, I wait, and if God opens a door, I step through. It’s led to some amazing, always private, friendships over the years.

That’s what I have to say to today’s returning vets: we have work to do. And the wonder, for us war-scarred types, is that it happens not in spite of the pain, but because of it.

Published on December 17, 2014 10:22

August 28, 2014

Dana's Cold Shower

This was the scene in our garden yesterday as our son-in-law, Dana Kintigh, dumped a big bucket of ice on his head. It was an especially meaningful contribution to the ALS drive, we all felt, as Dana's first wife died of this disease. He and our daughter Liz were married in June two years ago.

#wsite-video-container-129339922187093589{ background: url(//www.weebly.comhttp://www.elizabethshe... } #video-iframe-129339922187093589{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-129339922187093589, #video-iframe-129339922187093589{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-129339922187093589{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } }

#wsite-video-container-129339922187093589{ background: url(//www.weebly.comhttp://www.elizabethshe... } #video-iframe-129339922187093589{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-129339922187093589, #video-iframe-129339922187093589{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-129339922187093589{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } }

Published on August 28, 2014 15:54

May 4, 2014

The Dove

A small tragedy unfolded yesterday, literally at my feet. I was sitting on a bench outside our apartment building when somewhere overhead I heard a resounding bang. A second later, a mourning dove thudded onto the grass two feet in front of me. Lovely gray wings limp, small neat head twisted to the side, eyes closed – obviously it had struck a window in one of the units above.

A small tragedy unfolded yesterday, literally at my feet. I was sitting on a bench outside our apartment building when somewhere overhead I heard a resounding bang. A second later, a mourning dove thudded onto the grass two feet in front of me. Lovely gray wings limp, small neat head twisted to the side, eyes closed – obviously it had struck a window in one of the units above.I was staring at the motionless bird when with a rush of wings a second dove alighted beside it. I sat still, scarcely breathing, as the second bird pressed itself tight against the other and began a frenzied pecking at the ground. Tap, tap, tap with its sharp little beak. Get up! it seemed to be saying. Why don’t you move!

With a sudden shudder the fallen dove responded. As its partner’s tapping continued, it began beating the ground with its left wing. Faster and faster the wing flapped, till it flung the bird over onto its back. Now both wings flailed, battering the other dove which flew 20 feet away to the top of a railing. Arching, twisting, the struggling bird heaved itself back on its stomach, wings thrashing. “You can fly!” we urged it silently, its partner from the railing, I from the bench.

But with a final spasm the injured bird went still.

Did its partner know that it was dead? Or did it believe that the two might still soar together into the bright morning sky? It remained on the railing in unmoving vigil as five minutes passed. I sat still too, not to frighten it away. Ten minutes went by. Fifteen. How much longer might it have kept watch? An hour? A day? Doves, I knew, mate for life.

But a white terrier came yipping across the lawn and the waiting bird fled.

I stood up, the first movement I’d dared to make, gathered the warm little body in my hands and placed it beneath a shrub where later I’d dig a hole for it. I looked up at the apartments above me and saw what the bird had seen: in each window the perfect reflection of a cloudless blue sky, no slightest hint of danger.

All day I grieved, not just for that unsuspecting bird but for all bright young lives cut short in an instant. All the helpless whys pursued me.

This morning from the same bench I heard a mourning dove call. A common sound here, that plaintive oo-AH-oo-oo-oo. But today the wistful notes seemed to go on longer, and I imagined that it was the voice of that lonely partner. And listening, I knew that though we cannot know the why of untimely death, we can know what lifts it from the realm of cold, unfeeling chance. The little bird watching from the railing was part of a great web of connectedness that stretches from the least of us to the God who tells us that not even a sparrow – or a dove – can fall to the ground without his all-compassionate knowing.

Published on May 04, 2014 14:30

February 5, 2014

Meeting Taylor!

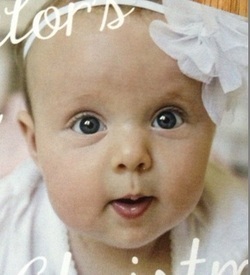

Our "Sixty and Ninety" celebration had a wonderful sequel when John and I continued south to meet our first great-granddaughter. This is Taylor Ann on the Hootens' Christmas card, but...

Our "Sixty and Ninety" celebration had a wonderful sequel when John and I continued south to meet our first great-granddaughter. This is Taylor Ann on the Hootens' Christmas card, but...

when we met Taylor in August, she was just 8 weeks. Granddaughter Lindsay with Taylor, while Papa John (naturally) takes over the kitchen, and Taylor's big brother Jackson creates a clay masterpiece. (Click photo to see it all.)

when we met Taylor in August, she was just 8 weeks. Granddaughter Lindsay with Taylor, while Papa John (naturally) takes over the kitchen, and Taylor's big brother Jackson creates a clay masterpiece. (Click photo to see it all.)

After furnishing Jackson's male-themed room , Lindsay went all ruffles for Taylor. Proud Great-Gran

After furnishing Jackson's male-themed room , Lindsay went all ruffles for Taylor. Proud Great-Gran

Papa John and Taylor gazing at each other across 90 years... and pretty pleased with what they see.

Papa John and Taylor gazing at each other across 90 years... and pretty pleased with what they see.

Published on February 05, 2014 15:02

January 30, 2014

Sixty and Ninety

Our son Donn is exactly 30 years younger than John. Well, almost exactly: John's birthday is August 2, Donn's, August 1. (I tried to hold onto the baby one more day, but babies keep their own calendars.) The two usually celebrate together -- but 2013 was a special milestone.

Our son Donn is exactly 30 years younger than John. Well, almost exactly: John's birthday is August 2, Donn's, August 1. (I tried to hold onto the baby one more day, but babies keep their own calendars.) The two usually celebrate together -- but 2013 was a special milestone. The "cake" is always watermelon!

Thirteen of us gathered at Lake Cumberland State Park in Kentucky. There was a cabin for each of the four couples and a separate one for five grandsons -- all in their 20s, with different concepts of bedtime from the older generations'.

Thirteen of us gathered at Lake Cumberland State Park in Kentucky. There was a cabin for each of the four couples and a separate one for five grandsons -- all in their 20s, with different concepts of bedtime from the older generations'.Our 6th grandson had a summer college course in Portland, Oregon, and none of our three granddaughters could join us: a priest-to-be settling into her new parish in Brooklyn, NY (see "Priest in the Family" blog,) a new baby in Atlanta (blog coming!) and a nurse at the bottom of the vacation pecking order at Brockton Hospital in Massachusetts. With me on the sofa in our cabin are John Scott and his wife Raena, and Donn with wife Patricia.

Raena and our daughter Liz proud of the party they and Patricia managed to pull off in this remote setting. The three daughters somehow assembled decorations --candles, crowns. party plates and napkins -- and snacks, salads and breads while...

Raena and our daughter Liz proud of the party they and Patricia managed to pull off in this remote setting. The three daughters somehow assembled decorations --candles, crowns. party plates and napkins -- and snacks, salads and breads while...

the three sons grilled chicken and steak on the charcoal grill just outside. Liz's husband Dana heads out with chicken breasts.

the three sons grilled chicken and steak on the charcoal grill just outside. Liz's husband Dana heads out with chicken breasts.

The birthday boys.

The birthday boys.

Lake Cumberland is a water sport paradise. Dana handling the rope while the boys took turns on an inflated raft. Later he joined the five 20-somethings diving from the roof of the catamaran.

Lake Cumberland is a water sport paradise. Dana handling the rope while the boys took turns on an inflated raft. Later he joined the five 20-somethings diving from the roof of the catamaran.

John Scott and Raena had other ideas about how to enjoy a boat trip.

John Scott and Raena had other ideas about how to enjoy a boat trip.  Donn at the wheel with son Andrew. These two are 31 years apart. A Sixty and Ninety-one birthday party in 2044??.

Donn at the wheel with son Andrew. These two are 31 years apart. A Sixty and Ninety-one birthday party in 2044??.

Published on January 30, 2014 18:51

January 23, 2014

A Priest in the Family

Last month John and I were in Garden City, Long Island, for the ordination of our granddaughter Kerlin to the Episcopal priesthood. With us were Kerlin's father and brother,who flew from Nashville to Boston so the four of us could take the train down to New York (no passenger trains where they live.)

"Magnificent" hardly does justice to the splendor of the ceremony at the cathedral. Next day there was a much smaller but equally meaningful service: Kerlin's first Eucharist as priest. Unlike a deacon, her previous status, a priest can consecrate the bread and wine, perform the other sacraments, and pronounce blessing. Kerlin outside "Bushwick Abbey," on December 8, her first Sunday as priest. The "Abbey" has no permanent home ("The church is the people, not the building," Kerlin reminded us) and its present venue is a radio station. "We want to serve people who might not enter a traditional church building." Here's the weekly transformation of a radio station into a worship space: a table with cloth & candles, a bowl for offerings ("Put money in or take out, at need," Kerlin prompts,) and on the stage a stool with four purple candles -- two lit this first Sunday of Advent. I don't know if you can make out the piano, drums and electric guitars that take the place of the organ in our conventional church back in Massachusetts.

Kerlin outside "Bushwick Abbey," on December 8, her first Sunday as priest. The "Abbey" has no permanent home ("The church is the people, not the building," Kerlin reminded us) and its present venue is a radio station. "We want to serve people who might not enter a traditional church building." Here's the weekly transformation of a radio station into a worship space: a table with cloth & candles, a bowl for offerings ("Put money in or take out, at need," Kerlin prompts,) and on the stage a stool with four purple candles -- two lit this first Sunday of Advent. I don't know if you can make out the piano, drums and electric guitars that take the place of the organ in our conventional church back in Massachusetts.

The chalice and patten handmade by a ceramicist friend of Kerlin's mother, Meg.

The chalice and patten handmade by a ceramicist friend of Kerlin's mother, Meg.

Kerlin at home with her nine-year-old son Adin. The blue hair is just the color of the moment -- last time we were together it was pink.

Kerlin at home with her nine-year-old son Adin. The blue hair is just the color of the moment -- last time we were together it was pink.

Kerlin's husband, Jordan Richter, "the real hero of the occasion," says Kerlin. Jordan had to leave his sound recording business in Oregon to be with her during her years at General Seminary in Manhattan, and now in Brooklyn, where care of their son is often daddy's job.

Kerlin's husband, Jordan Richter, "the real hero of the occasion," says Kerlin. Jordan had to leave his sound recording business in Oregon to be with her during her years at General Seminary in Manhattan, and now in Brooklyn, where care of their son is often daddy's job.

Four generations: father John, son, country music-writer John Scott Sherrill, grandson Peter, a recent college graduate with a degree in sound engineering, great-grandson Adin.

Four generations: father John, son, country music-writer John Scott Sherrill, grandson Peter, a recent college graduate with a degree in sound engineering, great-grandson Adin.  Adin reading to Papa John while his grandfather listens. Kerlin's sermons can be found on RichterFamilyAdventure.com.

Adin reading to Papa John while his grandfather listens. Kerlin's sermons can be found on RichterFamilyAdventure.com.

"Magnificent" hardly does justice to the splendor of the ceremony at the cathedral. Next day there was a much smaller but equally meaningful service: Kerlin's first Eucharist as priest. Unlike a deacon, her previous status, a priest can consecrate the bread and wine, perform the other sacraments, and pronounce blessing.

Kerlin outside "Bushwick Abbey," on December 8, her first Sunday as priest. The "Abbey" has no permanent home ("The church is the people, not the building," Kerlin reminded us) and its present venue is a radio station. "We want to serve people who might not enter a traditional church building." Here's the weekly transformation of a radio station into a worship space: a table with cloth & candles, a bowl for offerings ("Put money in or take out, at need," Kerlin prompts,) and on the stage a stool with four purple candles -- two lit this first Sunday of Advent. I don't know if you can make out the piano, drums and electric guitars that take the place of the organ in our conventional church back in Massachusetts.

Kerlin outside "Bushwick Abbey," on December 8, her first Sunday as priest. The "Abbey" has no permanent home ("The church is the people, not the building," Kerlin reminded us) and its present venue is a radio station. "We want to serve people who might not enter a traditional church building." Here's the weekly transformation of a radio station into a worship space: a table with cloth & candles, a bowl for offerings ("Put money in or take out, at need," Kerlin prompts,) and on the stage a stool with four purple candles -- two lit this first Sunday of Advent. I don't know if you can make out the piano, drums and electric guitars that take the place of the organ in our conventional church back in Massachusetts.

The chalice and patten handmade by a ceramicist friend of Kerlin's mother, Meg.

The chalice and patten handmade by a ceramicist friend of Kerlin's mother, Meg.

Kerlin at home with her nine-year-old son Adin. The blue hair is just the color of the moment -- last time we were together it was pink.

Kerlin at home with her nine-year-old son Adin. The blue hair is just the color of the moment -- last time we were together it was pink.

Kerlin's husband, Jordan Richter, "the real hero of the occasion," says Kerlin. Jordan had to leave his sound recording business in Oregon to be with her during her years at General Seminary in Manhattan, and now in Brooklyn, where care of their son is often daddy's job.

Kerlin's husband, Jordan Richter, "the real hero of the occasion," says Kerlin. Jordan had to leave his sound recording business in Oregon to be with her during her years at General Seminary in Manhattan, and now in Brooklyn, where care of their son is often daddy's job.

Four generations: father John, son, country music-writer John Scott Sherrill, grandson Peter, a recent college graduate with a degree in sound engineering, great-grandson Adin.

Four generations: father John, son, country music-writer John Scott Sherrill, grandson Peter, a recent college graduate with a degree in sound engineering, great-grandson Adin.  Adin reading to Papa John while his grandfather listens. Kerlin's sermons can be found on RichterFamilyAdventure.com.

Adin reading to Papa John while his grandfather listens. Kerlin's sermons can be found on RichterFamilyAdventure.com.

Published on January 23, 2014 15:36

January 8, 2014

Shopping in Small-Town France

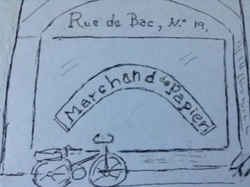

Shopping in France, outside the large cities, is an art apart. The unwritten motto of the small-town shopkeeper is, “I won’t sell it,” and of his customer, “I don’t want it.” On our first stay in a country town, years ago, John and I went at it all wrong. We needed stationery, and sure enough, on a shop window on the main street was printed in large letters:

Shopping in France, outside the large cities, is an art apart. The unwritten motto of the small-town shopkeeper is, “I won’t sell it,” and of his customer, “I don’t want it.” On our first stay in a country town, years ago, John and I went at it all wrong. We needed stationery, and sure enough, on a shop window on the main street was printed in large letters: Marchand de Papier

The sign, we soon learned, meant nothing. The fact that a man has set himself up as a paper merchant, acquired a supply of merchandise, and hung out a shingle to that effect, is no indication that this same man is interested in selling paper. On the contrary, he is simply a devoted paper fancier. He has founded his shop the way another man might found a bird sanctuary, as a kind of paper haven where large quantities of it are safe from the consumer.

An elderly man reading a newspaper behind the counter did not so much as glance up as we walked in. After an uncomfortable silence we ventured, “Bonjour, monsieur.”

He turned the page of his paper. The shop was dark and small and there was a great deal of paper stacked against the walls. None of it was covered, all of it was dusty, and some of it had begun to curl.

We stepped up to the counter. “Do you have any lightweight letter paper?” we asked.

That was our first mistake. The rest of the unspoken shopper’s rule is: if you want to make a specific purchase, don’t at all costs tell the shopkeeper what it is. The old man slowly turned his head and looked at us. He evidently didn’t care for what he saw, for he returned to his paper.

“Non,” he said.

We rephrased the question. “What do you have in the way of airmail stationery?”

He looked at us again. “Got no stationery.”

This was a barefaced contradiction of fact. His shelves were full of it. His attention was returning to his paper. Just in time, we stopped him. “Do you have any unlined paper?”

He stared at us again. “Mm,” he admitted at last.

“Will you show us what you’ve got?”

He sighed. He eased himself from his stool, laid down his paper, and led us to the rear of the store. “Voila.” He indicated a much-handled pile of pink letter- paper. It was certainly not air-weight and it was very soiled.

“Well,” we said hesitantly, “it’s not exactly what we…”

His relief was so evident that we looked at the pink paper again to see what treasure we had missed. He had turned and started back to his newspaper.

“But we’ll take it,” we added hastily.

His face fell. “Combien? How many sheets?” he asked, as if he hoped it would not be more than one, or two at the most.

“Twenty sheets,” we said.

He stared, unbelief written on his face. With the air of a man who performs a tragic duty, he counted out the sheets. We had intended to broach the subject of envelopes but in his heartbroken state over the loss of 20 pieces of paper, we could see that to part with as many envelopes would break him irretrievably.

“What do we owe you?” we asked.

He looked up, puzzled. It was clear that the question had never been put to him in just that way before. He examined us closely again, let his eyes run over the piles of paper stacked against the walls, gazed meditatively at the ceiling. “Ninety-four francs.”

Now John committed the crowning breach of etiquette by reaching at once for his wallet. A statement of price deserves the same thoughtful consideration by the customer as the shopkeeper devotes to it. The figure expresses both his judgment of you and his views of the world in general. The customer’s answering proposal does the same, and the final price agreed on is a monument to the democratic spirit.

But we, with our fixed-price bias, handed him a hundred-franc note without comment. He saw his loophole and seized it. “Pas de monnaie!” he said happily. “No change.”

We doubted this, but as we had no change either, it was clear that the shopkeeper considered the matter closed. He replaced the 20 sheets and pattered back to his stool like a man who has passed unscathed through a great danger. We, who really needed paper, pattered after him.

“Couldn’t we,” we asked (since the six francs in question amounted to something less than two cents) leave the hundred francs and the next time we come in…”

“Non,” he said.

He had won. We needed paper and had been unskillful enough to admit it. We retired, defeated but wiser.

* * * *

The next day we were back, armed with change in every denomination and determination in our hearts. Again, the man did not look up at our entrance. This time, however, we were not to be beguiled into speaking first. We gazed out the window, showing him that our being in his paper store in no way indicated an interest in paper.

Several minutes later a reluctant, “Well?” escaped from behind the counter. We chalked up one point for our side.

Well, we said, it looked like a good year for grapes.

Yes, he admitted, but the wheat crop was bad.

From the crops we moved to the weather, from the weather to the villainy of the government. In the midst of a heated discussion on how many members of the National Assembly should be lined up and shot, he asked us if we needed some paper.

Well, we said, now that he mentioned it, although we really didn’t want any, and would just throw it away when we got it, and had plenty already, and never used paper anyway – we might just look at some. In fact, now that we thought about it, the kind that interested us least of all was letter-paper, and as many as 20 sheets would be pure folly.

Thus agreed, we found ourselves back at the pile of soiled pink stationery. The sheets he’d counted out the day before were easily distinguishable as most of the dust had slipped off them. But he repeated the process of counting, then paused for a moment’s reflection.

“Seventy-three francs,” he said.

“Fifty,” we said.

“Sixty,” he said.

We were friends. We understood one another. We discussed the high price of gasoline and in less than half an hour more were bidding him farewell. Before we left, though, we made a few deprecatory remarks about envelopes just to lay the groundwork for our next purchase.

Published on January 08, 2014 21:58