Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 121

March 25, 2011

Retro Spring

This photo is for Lorianne, who has been delighting me with her photographs of dresses in windows for many years now!

We still have lots of snow on the ground in Montreal and few signs of spring other than longer hours of sunlight, so I smiled when I saw these fabulous dresses in the window of a retro shop on rue Rachel yesterday. Don't they just remind you of buttercups and chicks and Easter eggs? There were some terrific shoes and boots in the other window but I forgot to take a photo. Even the wire dress-forms are vintage in this shop. I've never gone in, but admit I'm tempted! On the other hand, the tiny waist I had at age 20 is a bit wider now and I don't think I could fit into either of these beauties.

Come to think of it, they kind of remind me of Elizabeth Taylor.

March 23, 2011

Sketching

This woman was on the metro recently, and I couldn't resist drawing her beautiful face and hair, set off by a big parka with a fur collar.

During the intermission of the concert I wrote about earlier this week, I had time to do a few sketches of other concertgoers nearby.

This elderly lady had a very thin face, and lots of lovely hair. She was all dressed up in her fancy glasses and pearls, and an elegant teal-colored dress, and she had a serenity that attracted me.

This couple was standing, talking to friends, at intermission. The woman kept moving but I was determined to draw her; she had beautiful black hair, a great face, and a fabulous black matador jacket with gold embroidery worn over corduroy pants. Her companion was as impassive as she was expressive.

---

It was last May when I started drawing again, after so many years of not. And although I haven't drawn every day, I've tried to keep at it. It makes me happy to see the practice paying off in greater ease, quickness, and assurance, just like it can with an instrument, a language, or a sport. With drawing, you are training not only your hand but your eye. This kind of fast drawing, of people or animals, is one of the best ways to improve because even if they're not moving right now, they will soon! You can't spend a lot of time being careful, you have to just look - memorize - quickly put it down - look again - and so on. And you have to learn what is essential in capturing a likeness - the shapes and angles formed by the bones of the face, the relative position of the features, the shape of the eyes and mouth, and the particular aspect of a person that helps give their "essence" and may be what attracted you in the first place: their hair, the hat they're wearing, their wild eyebrows, big sensuous mouth, their interesting posture, or whatever. All this thinking and decision-making needs to happen quickly, which is hard at first -- but what's gratifying is that it really does get easier.

And it's interesting to keep the work and go back to it after a while, because you are also learning to see its strengths and weaknesses, what could be improved, and how your line gradually becomes more assured. There's no substitute for practice.

I've been drawing, off and on, all my life, but I've always been too careful. When I started up again last spring, inspired by the work of the Urban Sketchers, I was very rusty. It took me a while to realize I didn't want to draw buildings and bridges and streets as much as I wanted to draw people, and it took courage to begin sketching in public places. Except for some life-drawing sessions back in the 1970s and 80s, this is the first time I've ever focused on quick portraits, probably because we moved to a city where I have the opportunity to take mass transit so often and to be in other large groups of people. I hope I can keep at it forever now, and keep on improving, and I want to encourage any of you who used to draw, or have always wanted to, to just jump in and try.

London artist Adebanji Alade recently posted his "25 tips for sketching on mass transit" and I've written to ask his permission to quote them here. He adddresses a lot of the qualms many people have about drawing in public. So stay tuned for that!

The recent series by illustrator James McMullen in the New York Times also struck a chord with many latent artists; his approach is a little too academic for me, but it may be very helpful for people who want some structure and a step-by-step approach to the process of drawing.

March 22, 2011

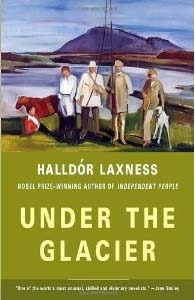

Under the Glacier

The first book by Halldor Laxness that I read, Independent People, is his most famous: the story of the unimaginably grim lives of Icelandic peasant sheep-herders. In spite of its darkness (and length - it goes on for some 512 pages) I loved the book, and was anxious to read another by the same author.

The first book by Halldor Laxness that I read, Independent People, is his most famous: the story of the unimaginably grim lives of Icelandic peasant sheep-herders. In spite of its darkness (and length - it goes on for some 512 pages) I loved the book, and was anxious to read another by the same author.

Under the Glacier is much shorter, and not grim at all; it's actually very funny. Susan Sontag, in her introduction, points out that it's unlike anything else that Laxness ever wrote, and goes on to describe how the novel can be seen as science fiction, dream novel, comic novel, sexual turn-on, and five or six other categories as well.

The young narrator is a wet-behind-the-ears emissary from the bishop (he calls himself "EmBi") sent to investigate rumors of the demise of Christianity in a remote town. The church, supposedly, is boarded up; the pastor's wife, of dubious reputation already when she came on the scene 35 years ago, has long since disappeared; the pastor is reported to have stopped celebrating the sacraments, particularly funerals; and there are alarming stories of someone or something unburied but instead stored in a casket on the glacier itself. Embi, knowing himself to be naive and unqualified, sets off to find out what he can and write a report for the bishop. He meets a bizarre collection of Icelanders at Glacier, all of whom proceed to give him a friendly but royal runaround. Their treatment of him is comic but also cruel, but the open-minded Embi takes it all with equanimity and a kind of dispassionate objectivity -- the only thing he complains about is the lack of any real food; he's expected to subsist on gallons of coffee and endless cakes -- until the pastor's wife reappears and takes him under her spell.

Sontag's assessment is witty and erudite (no surprise there) and the book, which truly is enigmatic, does not end with a neat summary of what this strange journey has been about. For me, however, this novel is primarily a fable that draws from the Icelandic saga tradition (particularly in its depiction of a shape-shifting woman, an enchantress deeply connected with mystical Nature and whose power over men is almost absolute) entwined with a journey into the largest and hardest human questions. As in Independent People, Laxness looks deeply into human nature and the resulting institutions and politics, but this time with a much lighter touch that never tips into caricature or overdramatization - flaws that I felt marred the concluding section of Independent People.

Embi's quest for the truth calls into question (and lampoons) the role of organized religion as well as that of New Age and quasi-scientific beliefs, while asking us to look more deeply at nature and our place within it. And to what lengths are we willing to go to find out the truth, after all?

I certainly don't have Under the Glacier all figured out; instead the book lingers in my mind and continues to ask questions - a quality that fulfills my test for excellence in literature.

March 20, 2011

The Universal Language

On Friday night, we went to a concert that I'd bought tickets for at Christmas, but it took on a special significance this week: the NHK Symphony Orchestra of Japan, conducted by Andre Previn, with Kiri Te Kanawa singing the "Four Last Songs" of Richard Strauss.

Before the concert, with the orchestra seated onstage, a spokesperson for the Place des Arts made a short speech. In typical Montreal fashion, it was delivered frst in French and then in English, expressing our sympathy to the Japanese people and acknowledging that the concert was an opportunity for us to be together in sadness and support. She welcomed Japan's ambassador to Canada, who was present, and the Japanese consul in Montreal. Then the orchestra's president came onstage, and spoke in Japanese, followed by a Japanese translator who repeated his words in French.

And then the conductor came on stage, supported by a cane - the aged, stooped and shuffling Andre Previn - and the orchestra began Bach's Air on the G String, in memory of those who have died. At the end, the entire audience rose to its feet.

Living in Montreal, I'm constantly aware of my language deficiencies. I've heard it said that some 130 languages are spoken here; at lunch with friends yesterday the conversation moved rapidly from French to Spanish to English and back again with an ease I envy and admire. After several years, my French is definitely improving; I read it well, can communicate in simple sentences, and understand much more of what's spoken than I ever thought possible. I've got a long ways to go.

But there is one written language in which I'm absolutely fluent, and that's music. Nobody talks about it very much as a language - of course we do, in general, but in the literal sense of a written language consisting of signs that the brain must learn and practice until one can easily decipher it, reproduce the symbols in one's head or in sound and thereby make meaningful -- not so much. Yet is there any language as universal as this? Western musical notation isn't the only way of writing symbols for musical ideas, but it is accepted, taught, and used all over the world by musicians who cannot begin to communciate with each other in a shared, spoken language. I find that incredibly wonderful. And for music that is not written down, skilled practitioners from any part of the world can still listen, pick up the rhythm or melodies or musical patterns, and join in -- and listeners can share it.

What we experienced last night was not a question of extraordinary music or performance, but of the unity of emotion that music can evoke. After singing the final words of the sublimely beautiful Strauss songs, -- "ist dies etwas der Tod?" / "is this, perhaps, Death?" written at the very end of the composer's life, Kiri Te Kanawa stood motionless as the orchestra played to the end. Then she turned to Andre Previn, and to the first violinist, who had played so well, and wiped tears from her own eyes. There were many Japanese people in the audience, who like me had probably bought tickets long ago, never expecting the catastrophies of last week. But the audience was representative of Montreal, too. We didn't share a spoken language, but it made no difference at all.

This is my contribution for the Language and Place Blog Carnival, hosted this month by Parmanu.

March 19, 2011

The Myriad and the Particular (4)

March 17, 2011

The Myriad and the Particular (3)

from my travel journal, handwritten on the flight south:

We had left the snow-covered earth behind and entered into a dim space above the indistinct but thick fog below, and a cloudy but brighter layer above.

Somewhere, about midway in our journey through this region, we came upon a little atoll of clouds. They were small and delicate and softly reflected the light of the unseen sun, still hidden above yet more layers of fog. These island clouds were bathed in a pale golden light and their tenderness touched something in me so suddenly and unexpectedly that I felt I might weep.

I brought my face close to the glass and looked down on them as if they were a dream of a place I must remember, and then they were gone behind us and their meaning -- in this middle world between fog and obscurity -- also stayed behind. But I continued to ponder them as we climbed out into that upper world, above all the clouds, where the setting sun reigned brightly, finally making himself known.

to be continued...

March 16, 2011

The Myriad and the Particular (2)

My beach friend found his two bottles, but when he unfurled the papers inside, neither one said anything surprising, or romantic, or even very interesting. Perhaps most people aren't terribly imaginative, but it doesn't stop us from sending messages and hoping someone will finally notice our tiny voice in its glass container, or on the Facebook page.

I sat on the beach made of millions of voiceless shells, thinking about human beings and their endless longing for connection, their almost-boundless capacity for hope; about the beauty of this peaceful sea that had gently cast up two fragile floating arks and about the thousands of bodies taken by the tsunami on the other side of the world, the thinner and thinner voices vainly crying for help coarsely mirrored in the cries of the gulls overhead.

Eventually it became too much, all this consideration of the many. And so my eye, seeking relief, kept noticing the individual: the bloom on a wild galliardia beneath the boardwalk down to the beach, the dead pelican, the stranded jellyfish, the horseshoe crab lifted out into deeper water, the subtle differences between cockle shells.

And in the airports, tired of reading, I pulled out my sketchbook and drew the people waiting alongside me: sleeping, resigned, fatigued, trying to go away and trying to come home.

Only hope can keep me together/

Love can mend your life/

Or love can break your heart/

I'll send an S.O.S. to the world/

Message in a bottle...

March 15, 2011

The Myriad and the Particular (1)

Yesterday I was on a beach where the sand was made of shells. Tiny shells, some still whole, in every shade from white to black and brown to lavender and palest pink, mounded into dunes that clicked faintly under my feet. Tiny shells, broken down by the waves into coarse multicolored gravel. Shells completely disintegrated into a powdery greyish-beige sand between my toes, a sand that could be lifted and blown onto the wind.

I sat on the dunes and watched the waves, eating a chicken sandwich, and two tangerines picked that morning from my aunt and uncle's tree. Pelicans flew down the length of the beach and splashed into the surf. An osprey hunted overhead. Gulls and long-legged shorebirds searched the shallows. Waves rose, broke, slipped onto the shore and retreated with a foaming edge of watery lace.

The shells were warm beneath me; I gathered a handful and let them fall through my fingers. The dunes and the beach stretched in either direction as far as I could see, and I thought, or tried to think, about the fact that each of these shells had once contained a life.

I had flown here before the disaster on the other side of the world, flown here watching the sun set over a thick blanket of clouds and rim the horizon with blood while the sky turned from turquoise to deepest azure and then lapis, punctured first by a planet and then by stars.The next morning, we woke to news of an equally incomprehensible magnitude. And yet, because it involves human beings, we cannot keep from trying to count and quantify and somehow contain the incomprehensible within a vessel of facts, because to do otherwise courts the disintegration of belief in the one life we comprehend, most of the time, as real.

There were very few other people on the beach, but I met a man walking in the same direction who came there once a week to look for special shells that he uses in his art projects. He was tall and tan, about my age, and wore shorts and a blue t-shirt, blue mirrored sunglasses, and a straw hat into which were stuck three feathers of different colors. We spoke for a few minutes -- Where are you from? Canada. Well this weather feels cold to us! How long have you lived here? All my life -- and then continued searching, separated by fifteen feet or so; he walked in the wet sand and I kept to the "shell line" that marked the extent of high tide. Every now and then he stooped down, and gave me something: a piece of soft green sea glass, a razor clam, a pair of matched cockles as big as my palm. Do you always find something special, I asked. Not always, he said, but usually...it depends when I come. But in the past year, it's been amazing, I've found two messages in bottles. Really! I said, and stopped walking. Yes, he said, I was amazed too, especially because I'd never found one before. And neither one had water inside, which is very unusual. One had a postcard in it, with writing in German -- I had to have someone translate it for me -- and that had been tossed in somewhere in the Atlantic. But the other had been put into the Baltic and had somehow come all the way around and washed up here after a journey of three years. He shook his head: So you never know.

- to be continued

March 6, 2011

What is "Success?"

Metro drawings, 3/3/2011

Standing in a big room full of Picassos, the first thought that presents itself is "absolute genius," quickly followed by two others, which immediately start fighting for supremacy: "How did he possibly get all this work done?" and "I am such a slouch!"

At MOMA, we saw a modest exhibit - not a big blockbuster, by any means - titled Picasso Guitars, 1912-1914. The room was filled with drawings, collages, and a few paintings and sculptures, from a breakthrough period of experimentation that spanned a mere two years. (Of course, Picasso was also doing work on other subjects at the same time.) We noted that, on one wall, a series of five or six collages represented a period of only two days, and traced a clear path toward realizing the goal that was expressed in the final work of the series. "That's the thing," said one of my companions. "He ws after something, and just kept working until he found it -- and even then kept moving on." And then he continued: "Doesn't It makes you want to go home and explore some of your own ideas with a lot greater focus?"

Absolutely. For me, there's nothing like being in a huge cultural mecca like New York to inspire and stimulate my own creativity. I was thrilled to share some celebratory moments with my friend Teju whose debut novel, Open City, is meeting with such critical acclaim; I was inspired by Picasso and a wonderful show of photography by women; happy to have deep and mutually-supportive conversations with literary, artistic, and musical friends, new and old; and breathed a great sigh of pleasure and relief at finding myself in The Strand, a huge, multi-floor English-language bookstore, filled with attentively browsing readers of literature, poetry, and art books.

On the drive home, my head was buzzing with ideas. Only after being here a few days, facing the blank screen and a studio full of art materials, did I come back to my own reality of having to make a living, do volunteer jobs I've promised, and take care of a house and a marriage - not to mention numerous other relationships and commitments, such as this blog! But the feeling has persisted that it's a good time to re-establish some priorities and focus, and so I've made time each day for my writing projects and for thinking hard about what's next. I'm going to continue to reflect on these questions in a deep way during Lent, which starts on Wednesday.

The time in New York has also made me think, "what is this elusive thing we call 'success?'" Actually, I wish we could throw the word out of our vocabularies, because "success" always seems to imply comparison to something or someone else, and as a result, we find ourselves pursuing goals that can never be reached. Our culture, with its cult of celebrity and wealth, reinforces our own insecurities, (and marketing, of course, uses that fact about human nature to make us feel inadequate and manipulate our behavior.) Many people who feel the stirrings of desire for self-expression are defeated before they even begin; others become dejected and discouraged at the rejections and disappointments which invariably accompany "going public" with the fragile flames of creativity that burn within nearly all of us.

There's no question that the artists whose work hangs in major museums were talented, but -- as Picasso's example shows us -- talent means nothing if we aren't willing to go into the studio every day and do the work. Success in the eyes of the world is quixotic, only given to a few, and often going away very quickly, so we need to be motivated by other things, such as the sheer joy of creating; the desire for self-expression and self-discovery; the challenge to grow and learn; the desire to create a body of work that says something about the arc of a human life; striving to do the very best work of which we are capable, and seeing each work as a stepping-stone to the next; realizing that doing creative work over a long time can be a path to wisdom.

For my own part, looking back over fifty-some years of practice in the visual arts, writing, and music, it's clear that my refusal to choose one of those areas and focus exclusively on it has limited my "success" as a pure artist, writer, or musician. On the other hand, my life has been immeasurably enriched by my stubborn insistence on working in all those areas, sometimes dropping one for a while, but basically continuing to pick up all three threads and bring them along. There was a time when I couldn't see how these threads added up to anything by a cloth full of holes; now I can see the wholeness - or even the holiness - these threads represent, because the decision to do this was truer to me than, for instance, dropping music from my life entirely. It's a path that has taken a different kind of intention and discipline than the five-hours-of-piano-each-day kind, and has at times involved plenty of confusion, self-recrimination, and doubt, as well as a great deal of happiness and satisfaction.

But that's my life. Each of us is different, and what will make each of our lives "a success" is something that we have to discover inside ourselves, not by having the world affirm us. Even the most acclaimed novelist or pianist still has to face the blank page or the next concert hall. So this isn't easy work, and it goes on for a whole lifetime, but I think it's a big part of why we're here. Art, defined in the broadest possible way, exists to help us discover ourselves, and gives us, every day, the opportunity for a new beginning.