Gene C. Fant Jr.'s Blog, page 3

February 3, 2014

“Extreme Religious Liberty Rights”

While most of the attention on the Supreme Court’s HHS mandate

cases has properly centered on whether the Court will interpret the protections

of the First Amendment and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to include corporations as well as individuals, an even more malignant threat to

religious liberty lurks just beneath the surface. Twenty-one years after the RFRA was introduced in the House of

Representatives by Chuck Schumer, passed nearly unanimously by Congress, and

signed into law by President Bill Clinton, the Freedom From Religion Foundation

has filed an amicus brief asking the Supreme Court to strike it down as an

unconstitutional “takeover of the Court’s power to interpret the Constitution”

and a violation of the Establishment Clause. Terming the protections of RFRA as

“extreme religious liberty rights,” the Foundation and associated groups go

beyond even what the Obama administration requests, asserting not only that Hobby

Lobby and Conestoga Wood don’t qualify for the law’s protections, but

rather that RFRA itself is unconstitutional.

There has always been some tension between the Establishment

Clause and the Free Exercise protections of the First Amendment, but the

Supreme Court, when considering a similar challenge to the Religious Land Use

and Institutionalized Persons Act in 2005wherein the Sixth Circuit Court of

Appeals had ruled that granting protections to religious prisoners amounted to

a violation of the Establishment Clauseruled that alleviating a state-imposed

substantial burden on religious practice did not violate the Establishment

Clause. The assertion that legislation protecting an individual’s practice of

religion amounts to an Establishment Clause violation would be a radical

departure from the nation’s history of allowing generous religious

accommodations. It would also open to challenge all sorts of currently

protected behaviors that amount to religious accommodation, including the

priestpenitent privilege and the conscientious objector exemption. These

accommodations arguably impose a burden on third parties, yet courts have

always viewed such burdens as necessary to the protection of a free society.

So though RFRA had near unanimous backing in 1993 and restores

the Supreme Court’s free exercise doctrine which was accepted from the 1963Sherbertdecision authored by Justice William

Brennan untilEmployment Division v. Smithin 1990, the applications of that

doctrine are now said to be “extreme religious liberty rights.” Unlikely as it

may be for the Court to go beyond the arguments presented by the parties

themselves to rule RFRA unconstitutional, the phrase “extreme religious

liberty rights” is one defenders of religious liberty ought to prepare to hear

a lot of in the coming years.

The Becket Fund website has links to all the amicus

briefs filed in these cases on both sides. The Freedom From Religion

Foundation brief is here.

A brief from constitutional law professors in defense of RFRA is here.

Thoughts On “Mitt”

I saw the “Mitt” documentary and here are some quick thoughts:

1. The first half of the documentary really shows how the Republican primary debates differed in the 2008 and 2012 cycles. Romney was by far the best Republican debater in the 2012 cycle. He didn’t win every exchange, but he won most of them, and it was clear which candidate on stage had mastered the form. Romney was fine in the 2008 debates. He was top tier. Romney’s debating certainly wasn’t a weakness, but he didn’t stick out as obviously the best. Did Romney improve between 2008 and 2012?

Maybe a little, but I think the big difference was in the competition. It is a lot easier for a quarterback to look good if the other team’s defensive line can’t bring pressure and their defensive backs can’t cover. Mike Huckabee and John McCain were more formidable debaters than any of Romney’s 2012 cycle Republican opponents. (Gingrich was as verbally talented as anyone, but he was so undisciplined and compromisedboth ethically and ideologicallythat he was sure to collapse as soon as he faced scrutiny.)

It wasn’t just the quality of the competition. It was also the dynamic of the debates. In the 2012 cycle, the right-of-Romney pack would focus their attacks on whoever emerged as the main conservative alternative to Romney. This happened right down to the very last debate where Ron Paul primarily attacked Rick Santorum. That made life a little easier for Romney. In the 2008 cycle, Huckabee and McCain (who both seemed to genuinely disdain Romney) attacked Romney more than they attacked each other. In the 2012 cycle, Romney’s less talented opponents were usually fighting a two-front war against Romney and the pack. In the 2008 cycle, Romney was fighting a two-front war against candidates more formidable than anyone he faced in the 2012 nomination contest.

This isn’t to take anything away from Romney. The Romney of 2008 was a better debater than the Romney who was defeated in debate by Ted Kennedy in 1994. The Romney of 2012 was a better debater than the Romney of 2008. Romney was a hard working guy who did everything he could to get the most out of his talent, but his 2012 Republican opponents made him look a little better than he really was.

2. In the documentary, whenever Romney is talking about the economy in (relative) privacy, he always talks about what some successful entrepreneur told him about economic issues. It was all about how this businessman had too big of a tax burden or how this other businessman never would have started his business in the current regulatory environment. Romney was an extremely opportunistic politician, but he seems to have been authentically unable see the world from the perspective of the employee who was anxious about stagnant wages or afraid of losing her health insurance. For Romney, the economic concerns of those people genuinely seem to be entirely derivative of the economic interests of those high-earners who “built that.” At least that part of his campaign was real. More is the pity.

3. The most famous part of the documentary is where Romney, after beating Obama in the first debate, goes off on how much more impressed he is with the life of his father George than with his own accomplishments. It is a touching moment. Both of Mitt Romney’s presidential campaigns were far better than the presidential campaign of his dad (which has been a punch line for two generations). Mitt Romney is still able to keep in perspective how impressive it was that George Romney was able to run a car company and become governor without the benefit of any money or much of an education. Mitt calls his dad the “real deal.” Running a contemporary presidential campaign is an enormously complicated undertaking, but it is also kind of a fake deal. John Edwards won a couple of presidential primaries. It was wonderfully non-egomaniacal of Mitt Romney that he could keep such a healthy perspective on his dad’s life.

First Links 2.3.14

The Art of Confession in an Age of Denial

Michael Jensen, ABC Religion & Ethics

Lunch with the Rector

Rosemary Ashton, Times Literary Supplement

The Prayerful Body of Coptic Christianity

Bishoy Dawood, Clarion Review

Apostles of Unreason

John Turner, Anxious Bench

The Rise of Islamic Finance

Mohammed Aly Sergie, Council on Foreign Relations

February 2, 2014

Muslims, Our Natural Allies

I am a Catholic. My Church teaches me to esteem our Muslim friends and to work with them in the cause of promoting justice and moral values. I am happy to stand with them in defense of what is right and good. And so I stand with the young woman in the above video in defense of modesty, chastity, and piety, just as I stand with Muslims like my dear friends Shaykh Hamza Yusuf and Dr. Suzy Ismail against the killing of unborn children and the evil of pornography, and with my equally dear friend Asma Uddin of the Becket Fund in defense of religious freedom. In the great document

Nostra Aetate, we Catholics are taught the following by the fathers of the Second Vatican Council:

The Church has also a high regard for the Muslims. They worship God, who is one, living and subsistent, merciful and almighty, the Creator of heaven and earth, who has also spoken to men. They strive to submit themselves without reserve to the decrees of God, just as Abraham submitted himself to God’s plan, to whose faith Muslims link their own. Although not acknowledging Jesus as God, they revere him as a prophet; his virgin Mother they also honor, and even at times devoutly invoke. Further, they await the Day of Judgment and the reward of God following the resurrection of the dead. For this reason they highly esteem an upright life and worship God, especially by way of prayer, almsgiving, and fasting.

Over the centuries many quarrels and dissensions have arisen between Christians and Muslims. The sacred Council now pleads with all to forget the past, and urges that a sincere effort be made to achieve mutual understanding; for the benefit of all men, let them together preserve and promote peace, liberty, social justice and moral values.

Let us heed this teaching. Let us, Muslims and Christians alike, forget past quarrels and stand together for righteousness, justice, and the dignity of all. Let those of us who are Christians reject the untrue and unjust identification of all Muslims with those evildoers who commit acts of terror and murder in the name of Islam. Let us be mindful that it is not our Muslim fellow citizens who have undermined public morality, assaulted our religious liberty, and attempted to force us to comply with their ideology on pain of being reduced to the status of second-class citizens. Let all of usChristians, Jews, Muslims, and people of other faiths who “esteem an upright life” and seek truly to honor God and do His willembrace each other, seeking “mutual understanding for the benefit of all men [and working] together to preserve and promote peace, liberty, justice, and moral values.”

Through the great work being done by my friend Jennifer Brysonwho is a devout Christian and a great American patriot who spent two years as an interrogator at GuantanamoI have met hundreds of religiously observant Muslims over the past several years and many are now my close friends. They are among the finest people I know. Like faithful Christians and Jews, they seek to honor God and do His will. They work, as we do, to inculcate in their children the virtues of honesty, integrity, self-respect and respect for others, hard work, courage, modesty, chastity, and self-control. They do not want to send their sons off to wars. They do not want their children to be suicide bombers. They do not want to impose Islam on those who do not freely embrace it. They thank God for the freedom they enjoy in the United States and they are well aware of its absence in the homelands of many of those who are immigrants. It is not right for us to make them feel unwelcome or to suggest that their faith disables them from being loyal Americans. It is unjust to stir up fear that they seek to take away our rights or to make them afraid that we seek to take away theirs. And it is foolish to drive them into the arms of the political left when their piety and moral convictions make them natural allies of social conservatives. (A majority of American Muslims voted for George W. Bush in the 2000 election. A majority of the general voting population did not.)

I admire Muslim women and all women who practice the virtue of modesty, whether they choose to cover their hair or not. There are many ways to honor modesty and practices vary culturally in perfectly legitimate ways. Men and women are called to serve each other in various ways, and women who refuse to pornify themselves, especially in the face of strong cultural pressures and incentives to do so, honor themselves and others of their sex while also honoring those of us of the opposite sex. They uphold their own dignity and the dignity of their fellow human beings, male and female alike.

I have no doubt that in certain cultures, including some Muslim cultures, the covering of women is taken to an extreme and reflects a very real subjugation, just as in sectors of western culture, the objectification of women (including the sexualization of children at younger and younger ages) by cultural pressures to pornify reflects a very real (though less direct and obvious) subjugation. But, of course, we are in the happy position of not having to choose between the ideology of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and that of Hugh Hefner.

Of course, defenders of pornification claim that they are “liberating women” and “celebrating female beauty.” The liberation claim is the very reverse of the truth. As for “celebrating female beauty,” let me ask you this: Is there an actress in all of Hollywood who when appearing at one of these absurd awards shows dressed in a see-through gown, bra-less and wearing a thong, can compare with the beautiful young Muslim woman in the video I posted? I submit that there is none. Oh, yes, to be sure, the actress will appeal to

something in her male viewers. (I’m a man.Take it from me.) But it will not be their sense or appreciation of beauty. It will be something much lower and brutely appetitive. Their experience will be one in which who she actually is as a person is utterly submerged. The men viewing her will not be drawn in to wonder about her thoughts and feelings, her experiences of joy and sorrow, her strengths and vulnerabilitiesthe things that actually make her the unique person she is. Their experience will, quite literally, be an experience of de-personalized desirethe very definition of lust.

February 1, 2014

Carl’s Rock Songbook #91: Love, “Alone Again Or”

Here’s a song that knows what it is to feel loneliness midst the Summer of Love:

Yeah, I heard

a funny thing:

somebody

said to me,

that I could

be in love, with almost everyone.

I think that

people are, the greatest fun

and I will

be alone, again tonight, my dear.

With “Alone Again Or”, the rock

band named Love explored a basic problem with what their fellow hippies were

saying about Love. It was fine to seek

to love everyone, say, to get a charge from the reciprocal vibe of brotherly

love at the Happening, but this would never quite feel like falling in love,

and having that love returned. That love,

eros, spoke to a more primary

need. And without the need tended to,

the practice of brotherly love could still leave one feeling alone. Yet again.

In a number of recent Songbook posts, I’ve explained how the

hippie tendency was to combine and conflate three different sorts of love: 1) a brotherly love for all mankind, 2) eros, the sort of love that makes you

fall for a particular man or woman, and 3) free-love.

It’s fairly obvious how, midst this conflation, some might

think that 1) was more easily realized if one engaged in 3). Next time, when I consider the film Taking Woodstock, I’ll say more about

that aspect of the conflation. And of

course, everyone knows that the line separating 2) from the broader “lust” that

fuels 3) is anything but a neat onearguably, the hippies attempted nothing

terribly new by trying to more thoroughly blend those.

But these combinations are less interesting than that of 1)

and 2), the one explored by “Alone

Again Or.” The narrator is initially open to the idea touted in a song like Jefferson

Airplane’s “Let’s Get Together” of trying to love everyone, but finds that it

fails in practice. He says, “No, that’s

not doing it for me. And no, that’s not

really what I mean by love. What I want is you. Your

love and your presence.”

The first stanza sets up the divide between the song’s lover

and his beloved:

Yeah, said

it’s alright:

I won’t forget,

all the

times I’ve waited patiently for you,

as you do,

just what, you choose to do

and I will

be alone, again tonight, my dear.

This beloved apparently expects her lover to accept her free-choosing

not-tied-down ways, to say about them yeah,

it’s alright. Now these could be

any sort of selfish ways that leave the narrator waiting for her and spending a

number of nights alone, but here’s a further interpretation: just as he initially seems to affirm the

touted hippie embrace of fraternal love with the second stanza’s yeah, he initially seems to affirm the expected hippie acceptance of open-relationships with the

first stanza’s yeah. The repeated pattern asks us to connect the

two apparent affirmations. Such connection makes more sense if what the first stanza suggests is not simply that his beloved expects him to accept her freedom on her own terms, but that she further does so in the name of the new free-love. Isn’t her lover hip?

Whatever he might say,

the narrator is unhappy about her treatment of him. It’s actually not alright. Songbook readers might recall certain lines

from that other song on Jefferson Airplane’s first LP, “And I Like It,” where

the singer says, This is my life, I’m

satisfied. So watch it babe, don’t try

to keep me tied. In the first stanza

of “Alone Again Or,” if my interpretation is correct, we’re given what the

other side of that feels like, particularly if the other side is really in love.

So, while there’s only two brief stanzas (the

second repeats), they pose the real and perhaps impossible-to-satisfy longing

of erotic love, against at least one, and perhaps two, of the cheery new love-substitutes/supplements

recommended by the new hippie creed.

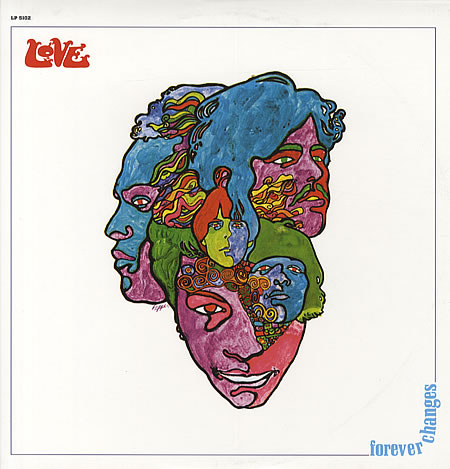

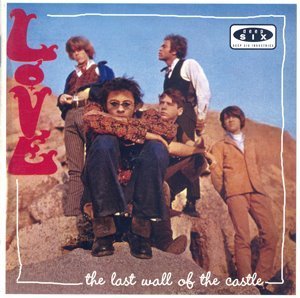

Now a bit about the band for those who haven’t heard of

them. Nearly every connoisseur of 60s

rock loves Love. While they did not seek

or win much popularity beyond their LA base, they produced one fine folk-rock/gargage

LP, Love, and two LPs that easily

stand among very best of the era, Da Capo

and Forever Changes. The latter

is particularly praised, both for one of the best uses of orchestral strings in

rock and its lyrical sophistication. That praise is deserved, but for me it’s Da Capo that is the real knock-out, as a briefly described in

Songbook # 44.

Their name always had an ironic aspect to it. Yes, “love” was the watchword of the

folk-rock songs, and sure, Love were right there with what was hip and au courant, penning their share of love-celebrating

songs, and saying, in the pantheistic blather of the times, that they wanted their

music to “engulf the listener as love engulfs the world.” But Love evinced a tough side also, recording a number of remarkably angry songs: the garage-punk classic “My Flash on You,” one

the fastest versions of “Hey Joe,” a

cover of “My Little Red Book” that ditches the lost-love vibe of the

original, and finally “7 and 7 Is,” a breath-taking hardcore punk prototype

from early ’67, complete with a nuclear explosion finale and lyrics about

throwing one’s Bible in the fireplace.

By late 1967’s Forever

Changes, this more aggressive musical side had melted away, and the gently

sad Spanish-y drama of “Alone Again Or” shows just how potent their artistry was

in its more pensive mode. Still, a certain

tension between their cynical side and their wistful one remained, sometimes embodied in the

different lyrical approaches of leader Arthur Lee, and of Bryan Maclean, the writer of this song. Both contributed to the general feeling of The Search that pervades Forever Changes, culminating in one of the most honestly philosophical of rock songs, “You Set the Scene.” The original

line-up was fired by Lee 1968, and despite all his musical genius, he was not

able to assemble another group worthy of the name.

Now if I could just understand why Maclean put the word “Or”

in the title of this song. Any ideas?

January 31, 2014

Postmodern Conservatism and Libertarianism

Many conservatives say that those darn progressives are making our country more collectivist. And one result is the growing culture of dependency. We’re getting further and further down that “road to serfdom.”

My own postmodern and conservative view is that the era of big government is more over than not. Not only that, collectivism is dead and progressivism is on life support, unless it’s the kind of half-libertarian techno-progressivism promoted by Silicon Valley. It’s not that the various new births of liberty have been chosen by Americans. They would, if they could, chose against the cutting back of Medicare and Social Security. They are, we might say, conservative in the precise sense, wanting to keep what they have, just as most of them would rather keep their excellent employer-based health insurance. But for a variety of reasonsbeginning with our demographic crisis, what we have now is unsustainable.

I tell young people that I have a two-point program for them to follow rigorously to save our entitlements. First, start smoking and really stay with it. Second, starting having lots of babies, beginning today. If we continue our individualistic trend of living longer while generating fewer replacements, then there just won’t be enough young and productive people around to pay for the benefits of the old and unproductive ones. Social Security and Medicare depended on the demographics of the late Fifties and early Sixties. If men would kept dropping dead in their fifties while having three or more kids, Social Security could have been a Ponzi scheme with a kind of indefinite longevity.

We can also see that the imperatives of the 21st century global competitive marketplace overwhelm every effort to resist. Employer and employee loyalty have little future. Tenure is toast. So are unions and pensions. Every educational expert seems to agree that we have to reconfigure education to give students flexible skills that they can sell their labor piecemeal as independent contractors to whomever needs it at the moment. Those same experts say that the endlessly disruptive imperative of productivity will transform all of our institutions.

Are these changes good? Libertarians say yes, because liberty and prosperity are the bottom line, even if the prosperity isn’t shared by those who don’t earn it. Traditionalists and integralistsfollowers of Patrick Deneen and Alasdair MacIntrye and the Canadian George Grantsay no. America is a techno-productive wrecking ball that endlessly undermines the relational and communal lifethe orientation around family and friends, God and the goodthat make life worth living. We postmodern conservatives say yes and no. We’re happy to live in a free and prosperous country and not in an Aristotelian polis or a medieval village or even in a Benedictine monetary. But we’re getting more and more troubled about the way recent social and economic developmentssuch as jobless recoveries, the shrinking of the dignified and responsible middle class, the increasingly pathological family life of the bottom half of the middle class, the soaring number of single moms, the growing number of detached and irresponsible men of almost all ages, the coldness of our “cognitive elite” toward those not of their kind, and the atrophying of our mediating institutionsare emptying out the relational contents of our free, personal lives. Still, there’s plenty of good about living in America, as I see every day in the patriotic, familial, Christian, charitable, entrepreneurial, techno-savvy, honorable, violent, and leisurely South.

All this is a prelude to calling your attention to something I just wrote in response to a piece of libertarian complacency. It’s part of the great tradition of postmodern conservatism to shamelessly promote our work elsewhere.

First Links 1.31.14

The Nautilus on the Cathedral

Rev. Tim Schenck, Clergy Family Confidential

An Altar on the Farm

Phillip Jensen, Comment

The Apocalypse in America’s DNA

Stefany Anne Golberg, Smart Set

Back to (Divinity) School

Sarah Pulliam Bailey, Wall Street Journal

Recklessness and Resignation: Democracy in a Time of Crisis

Daniel Cohen, Los Angeles Review of Books

January 30, 2014

B. B. Warfield and Charismatic History

Dale, I agree with you that the history of Protestant claims in favor of continuing charismata should not be inadvertently denied, and that Protestant discussions of charismata should not become a stalking-horse for Protestant-Catholic controversies that are essentially irrelevant to the discussion. I do not share the desire of some of my more enthusiastic but less wise Reformed friends to cast charismatics beyond the pale of Protestantism; even when we turn from the less wise among my Reformed friends to the more wise, I think we still speak confusedly in this areawe have to stop talking as if all aspects of Reformed theology shared the status of those great central pillars that define Protestantism, such as justification without the works of the law.

Those central pillars, which are core to Reformed theology, are indeed paradigmatic expressions of the Reformation. But they are not paradigmatically Protestant because they are core to Reformed theology, and we have to stop talking about other aspects of our theology as if they, too, were core Reformation doctrines. Our Lutheran friends, to say no more, could raise a plausible objection! The real variety of Protestant belief and practice is too rarely accounted for in the way Reformed people use the term “Protestant.”

However, I don’t think B. B. Warfield always shares that tendency in Counterfeit Miracles. He does sometimes slip in that direction. On the whole, however, I think he does a better job than you give him credit for.

He did identify opposition to Rome’s claims of continuing charismata as a core Protestant commitment, including some language much stronger than what you quoted. The first two sentences of Chapter 4 are: “Pretensions by any class of men to the possession and use of miraculous powers as a permanent endowment are, within the limits of the Christian church, a specialty of Roman Catholicism. Denial of these pretensions is part of the protest by virtue of which we bear the name of Protestants.” He then approvingly quotes another author who writes that Protestants don’t see a promise of continuing charismata in scripture.

But look more carefully at those first two sentences, and then compare them to what comes in the paragraphs that follow. In spite of that troublesome third sentence, overall Warfield seems to me to be setting up a contrast between Protestant-Catholic debates over charismata (the subject of Chapter 3) and intra-Protestant debates over charismata (the subject of Chapters 46). I think he wants to draw attention to how these debates are different in characterprecisely the distinction you want to remind us of.

Note Warfield’s precise phrasingthe key words in the first sentence are “class of men” and “permanent endowment.” This is in contrast to the way he characterizes Protestant belief in charismata, which he describes as claims to the possession of gifts by “individuals”that is, individuals qua individuals. These Protestant claims are different in kind precisely because they do not elevate a special “class of men” who have a “permanent endowment” of miraculous gifts, as the Roman claims do. I am open to correction if I have misunderstood Protestant charismatic theology, but if I understand it rightly, then Warfield’s statements in the first and second sentences are correct; opposition to the particular claims Rome makes about continuing miracles is, in fact, core to Protestantism. They are so not because Rome claims miracles continue to occur, but because Rome claims these miracles occur in such a way as to require the priesthood to mediate in an authoritative way between the believer and Christ.

In Chapter 3, his focus was on the connection between Rome’s belief in continuing miracles and its doctrine of the authority of church tradition. On both these issues I think he’s right; standing against the mediation of the priest and the coordinate status of church tradition alongside scripture are core to Protestantism.

In the argument that follows, Warfield does not depict Protestants who believe in continuing charismata as some sort of infection of crypto-Catholicism. To the contrary, he offers a theory as to why some Protestants accept continuing charismata that is grounded not in Catholicism (not even in a sort of unintentional semi-Catholic compromise on soteriology by those dastardly Arminians) but precisely in the nature of Protestantism itself. “Protestantism, to be sure, has happily been no stranger to enthusiasm; and enthusiasm with a lower-case ‘e’ unfortunately easily runs into that Enthusiasm with a capital ‘E’ which is the fertile seed-bed of fanaticism.” I do not think I have ever heard an apologist for Roman Catholicism who did not say something almost identical to this sentence about the nature of Protestantism, though of course with a different end in mind. It is not an especially charitable view, and can be criticized for that reason. But it is not conflating Catholic and Protestant views.

The very fact that Warfield devotes one chapter to Roman Catholicism and three chapters to Protestant claims in favor of continuing charismata is telling. (The chapter on the patristic and early medieval church is not about Catholicism. Warfield of all people would have been the last to cede figures like Augustine to Rome; in his majestic essays on Augustine and Pelagius he famously remarked that the debate over the Reformation was really a debate between Augustine’s doctrine of grace and Augustine’s doctrine of the church.) Warfield is against all claims of continuing charismata, andalashe does not always treat them charitably. But he does give the presence of those claims within Protestantism a pretty full representation.

You’re right that some of my Reformed friends need to quit trying to read charismatic claims out of Protestantism. But Warfield was better on these issues than they are.

Equivocation and Contraception: A Response to Rachel Held Evans

Rachel Held Evans has recently written a lengthy blog post expressing her take on the morality of contraception. She says that evangelical

thinking on the matter has been distorted by “male privilege” and by misguided

statements from Republican politicians.

In the background of her discussion are the many

Christians who have been raising religious liberty concerns about Obamacare’s

contraception mandate. She says that evangelical objections to the mandate have

been misinformed and that Christians need to “avoid making generalizations

about the millions of women and families who say they would benefit from

affordable, accessible contraception.”

Readers might be surprised to learn that Evans identifies

herself as a “pro-life” Christian, even as she admits that she finds it hard to

believe that human life begins at conception. Even though the moral status of

the unborn is the central issue, she

dubs the matter a “rabbit trail.” We are sure we are not the only ones who find

her “pro-life” claim to be quite unconvincing. Her uncertainty about the status

of the unborn is the exact type of equivocation that makes progressive evangelical

ethics problematic and myopic, as one of us has written elsewhere.

In any case, this is not even the central weakness of her

article. In making the case for contraception, she fails to engage the central

moral reasons that evangelicals and Roman Catholics have opposed the Obamacare

mandatethat it requires them to participate in morally reprehensible behavior

and runs roughshod over religious liberty.

Evangelicals and Roman Catholics agree that many of the

birth control technologies mandated by Obamacare can induce abortion. Evans

denies that this is a legitimate concern for birth control pills. Then,

astonishingly, she concedes that even with the pill, “There’s the very remote

chance that fertilization will somehow manage to occur. In this case the zygote

will probably fail to implant on the uterine wall.” Since she is not sure

whether life begins at conception, it is not surprising that this possibility

does not trouble her. But it is quite troubling to those of us who are actually

pro-life.

Obamacare also requires coverage for IUD’sa technology

that everyone agrees to have an abortifacient mechanism. Evans does not even

acknowledge this as a problem. Again, where is her “pro-life” concern? She

raises no moral qualms about destroying human life at its earliest stages with

IUD’s.

Evans also denies any moral concerns with so-called

“morning after pills.” She argues that “Plan B does not inhibit implantation but

instead blocks fertilization.” What she fails to acknowledge is that Plan B is

not the only morning-after pill mandated by Obamacare. Ella is also covered

under the mandate, and the studies that appear to vindicate Plan B do no such

thing for Ella. The FDA still lists an abortifacient mechanism of action for

both of these drugs, but again Evans does not inform her readers of these

facts.

Evans also fails to engage the religious liberty concerns

of evangelicals and Roman Catholics. The contraception mandate requires

pro-life business owners to purchase insurance plans that cover

abortion-inducing technologies. We believe that this mandate represents one of

the most egregious violations of religious liberty in American history. Evans

does not have to agree with pro-life concerns about the morality of these

technologies. But why is she taking the side of Caesar against pro-life

persons with sincere religious objections? How can she possibly support forcing

Evangelicals and Catholics to participate?

Evans concludes her article saying, “Christians especially

must be committed to telling the truth and getting our facts straight, or else

we risk losing credibility in the conversation and leading the faithful

astray.” We couldn’t agree more. But in this case, Evans is the one who needs

to get her facts straight, not Evangelicals and Catholics who stand on

principle against the Obamacare mandate.

Denny Burk is the author of What Is the Meaning of Sex?.

He also writes a daily commentary on

theology, politics, and culture at DennyBurk.com. Andrew Walker is the Director

of Policy Studies for The Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.

Leo Strauss for Believers

These thoughts are offered as an addendum and complement (mostly) to Peter Lawler’s recent “Leo Strauss and Postmodern Conservatism.”

Whatever Leo Strauss’ personal disposition on the question

of Biblical religion (and he certainly seems not to have been a believer in any

familiar sense), he remains an indispensable thinker for believers because of

his unrivaled deconstruction of the faith of modernity. The modern rationalist critique of religion

is itself based, he shows, on an unexamined faith in the mastery of nature as

the end of knowledge. This critique is

invaluable to all who would resist the blind colossus of modern rationalism,

whatever we think of the alternative Strauss proposedi.e., the alleged

self-sufficient goodness of philosophic inquiry itself. And this proposed Straussian solution appears

much more nuanced and deliberately political, I believe, on close

examination.

Leo Strauss offers the most perspicacious critique of modern

rationalism because he never loses sight of the question of the good of

thinking, and therefore of the problem of the relation between theory and

practice. The moderns deny the linchpin

of classical thought, the intrinsic good of philosophizing, and thus make

knowing instrumental to power. Power in

turn can only be interpreted according to the most “natural,” that is,

universal, human needs and appetites (at least until Nietzsche’s attempt to

liberate the will to power from this democratic conception of nature).

Leo Strauss understands that the modern critique of the

intrinsic good of philosophy is derivative of the Christian critique of pagan

pride. Modern materialistic universalism

is both directed against and borrowed from the hopes of Christian spiritual

universalism. The collapse of the

Christian synthesis of Greek reason and Jewish revelation produces the modern

project of a new, secular synthesis.

Strauss does not publicize the affinities or parallels

between the Christian and modern syntheses, because he values a practical

alliance with Christian natural law, and because he prefers to hold the

founders of modernity rationally accountable. Only if we consider the rise of modern universalistic hopes as a

rational project can we hold modernity rationally responsible, and thus hold

open the possibility of a more responsible view of reason. It is thus on eminently practical grounds

that Strauss resists portraying modernity as the “secularization” of

Christianity (as in Voegelin’s “immanentization of the eschaton,” for

example).

The alternative Strauss presents to blind modern “rationalism”

is classical natural right, which amounts to the rule of the wise, where

wisdom is grounded in the alleged self-sufficiency of the goodness of

philosophizing. Strauss knows full well

that this assertion of self-sufficiency is a prolongation of aristocratic

pride, and he’s for it precisely for that reason. The nobility of philosophy serves him as the

anchor of virtue and excellence more generally. Thus a moral-political concern lies at the esoteric heart of Strauss’s

recovery of “political philosophy,” and the political is much more than an

exoteric front or a ladder that is finally kicked away.

Strauss is very aware of the one-sidedness of this grounding

of morality and politics. He is aware

that his aristocratic strategy gives short shrift to another dimension of

morality and indeed of the meaning of human existence. This is the dimension he refers to, as it

were in passing, when he asserts quite flatly that humanity is unthinkable

without reference to “sacred restraints.” We are subject to mysteriously grounded limits, divine commands that

cannot be accounted for from the perspective of the nobility of aristocratic

self-sufficiency. These commands issuing

from a divinity beyond the reach of reason connect us with the universality of

humanity and with common human hopes for the redemption of what is dearest to

us as simple human beings. This is to

say, the reference to an author of mysterious “sacred restraints” connect us

with personal love.

But Strauss judges it best not to get philosophy mixed up in

the articulation of personal love or hopes of universal salvation associated

with love; instead he prefers to keep sacred law separate from the nobility of

philosophy, Jerusalem (i.e., Judaism) separate from Athens. Reason on the one hand, and divine law on the

otherand never the twain must meet.

Strauss must know that this strategy is quixotic, since as

soon as he says we must be open to the excellence of philosophy and to the

obedience of the pious, he has made it impossible not to wonder how these dispositions

can be integrated, or at least held together in the same soul. But Strauss suppresses any such integration

because he abominates the modern synthesis, which binds philosophic excellence

to the project of universal salvation.

One might say that Strauss believes that Hegel is not simply

wrong when he presents the culmination of rational universalism as the

fulfillment of Christian revelation. And

I do not believe Strauss is simply wrong in his resistance to the Christian quest

for synthesis, for the attempt to combine reason with love does indeed tend in

the direction of modern rational universalismof universal “recognition” and “satisfaction”

in a homogenous state.

In other words, Christianity is vulnerable to co-optation by

“social justice,” since its Jewish humility undermines aristocratic

pretensions, and its Hellenism undermines the particularity of Jewish

commandments. To be sure, Christians will appeal to “conscience,”

and to the mediating authority of the Churchbut can these avoid borrowing content from Jerusalem and Athens, from

sacred commands and from the pride of human nature?

The only brakes on the secular appropriation of Christian

humility and universalism are Jewish law and pagan honor.

Postmodern conservatism is postmodern because it aspires to

no final synthesis of Jerusalem and Athens that would provide wholly rational

foundations for morality and politics. It is conservative because it sees the truth

in both Jerusalem and Athens, and therefore the partial and dangerous truth in the

drive to synthesize them.

None of this would be possible without Leo Strauss. He reminds us that Christians are not exempt

from the deeply political responsibility of reason.

Gene C. Fant Jr.'s Blog

- Gene C. Fant Jr.'s profile

- 2 followers