Daleen Berry's Blog, page 5

September 11, 2015

“American Pain” a Fascinating True Tale of Greed, Addiction, and Pill Mills

If you don’t know anyone who’s been addicted to narcotic painkillers, you’re fortunate. Sadly, most of us do, or did, in the case of an addict whose addiction ended in death. It’s not a pretty topic—but it certainly is a crucial one.

Last fall I joined a local writer’s group made up largely of WVU professors. We email each other pages of our current project and meet once a month to provide feedback. It’s probably the best writer’s group I’ve ever been involved with, and I enjoy it immensely. One of the members, John Temple, was working on a nonfiction project he was under contract to finish. The early drafts of American Pain: How A Young Felon and His Ring of Doctors Unleashed America’s Deadliest Drug Epidemic really grabbed my attention. In part because I lost a sister to drug abuse, after she got hooked on those nasty painkillers, and also because I’ve had several surgeries myself and almost every single time I was sent home with a prescription for an opioid—which is a synthetic form of opium. Most of the time, I didn’t even need to fill the script. Other times, if I did, I rarely finished the pills, and flushed those that remained down the toilet.

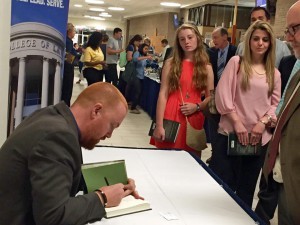

John Temple, a WVU journalism professor, signs copies of his new book, American Pain: How a Young Felon and His Ring of Doctors Unleashed American’s Deadliest Drug Epidemic at his August 31 book launch. [Photo by Benyamin Cohen]

Then, on Monday, August 31, 2015, I attended Temple’s book launch at the WVU Law School. There, a three-member panel composed of a psychologist, an attorney, and Temple, discussed the painkiller epidemic. I thought I knew how addiction worked, but I learned even more that night. For instance, the more painkillers you take, the more pain you have. That’s the word from Dr. Carl Sullivan, director of the West Virginia Addiction Training Institute for the last 25 years. Once the brain becomes accustomed to painkillers, any real or perceived pain seems even worse, which prompts the user to feel like he needs more pills at higher doses. It’s a vicious cycle that turns many people into addicts and eventually leads them to heroin.

Sullivan knows addicts. Prior to 1985, most of his patients were alcoholics. But in the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began pushing drugs like OxyContin, saying that opioids were safe. They pushed them right into West Virginia, which has a large worker’s compensation population, due to such dangerous jobs as cutting timber and mining coal. At the same time, pain became the fifth vital sign doctors would check when examining patients. Because pain isn’t easy to quantify, and it’s impossible for doctors to confirm if a patient doesn’t have any, “doctors felt compelled to treat it,” Sullivan said. The result was a perfect storm here in Appalachia and elsewhere. “Opioids in West Virginia were just flowing like water,” he added.

We can thank Purdue Pharma for this change in the medical community. In the early 1990s, Purdue developed OxyContin, a controlled-release pill. It would replace MS Contin, one of their other drugs, used only to treat cancer patients. As Temple writes in American Pain, “Purdue wanted OxyContin to be prescribed to a much broader array of patients and for a longer period of time.” So Purdue began a major marketing campaign: first, they educated the American public about the problem of untreated pain. Then, they provided the solution—their new drug!

When West Virginia figured out what was going on with pill mills, Temple said, it became one of the first states to clamp down on the problem, which included patients who would doctor shop and buy far more painkillers than they needed. “The drugs may go away but not the addiction, so you go where the drugs are,” Temple said. Thus the reason West Virginia residents, like many people in southern states, began driving to Florida to get their fix.

The morning of the book launch, Sullivan treated 23 patients. All of them were addicted to opioids. These and other addicts have symptoms that include an intense craving for painkillers, being restless, sweating, vomiting, diarrhea, and thinking only about one thing: getting more drugs. “Without treatment, nothing good happens,” Sullivan said, “squalor, death.”

Not long ago he felt hopeless. Since then, new treatment programs are helping people addicted to painkillers. The clinical psychologist said he “feels more optimistic in 2015 than in a long time.”

Who would believe that this painkiller epidemic started, in large part, because of a construction worker–and felon–in Florida? The story of their American Pain clinics and the drug-dealing doctors who worked for them is amazing! Temple spent three years writing his book while on sabbatical from WVU, where he teaches journalism.

Not only is his writing crisp and clear, but Temple also cites fascinating numbers that help tell the story of this American epidemic. For instance, Temple says that during one period, Florida doctors bought nine times more oxycodone (the main ingredient in OxyContin and other painkillers) than doctors in other states. “That’s nine times more than the other forty-nine states combined,” he says. Records from the Drug Enforcement Agency show that in “one six-month period,” Temple says, “Florida doctors bought 41.2 million doses while every other physician in the country collectively purchased 4.8 million doses.” In fact, he says “four of [American Pain’s] clinic’s full-time doctors ranked among the top nine physician purchasers of oxycodone in the country.”

American Pain got its start, in part, from a health care industry that comprises 18-percent of the U.S. economy, according to Valerie Blake, a WVU associate law professor. That’s huge, and it’s climbing. When the pill mills were pumping out pills so fast almost no one could keep count, Florida then had virtually no laws regulating health care, Blake said. And the state certainly had no database to help track patients who were “doctor shopping.” Nor did it have any laws that stipulated who could or couldn’t own a medical clinic, she added.

Enter the George brothers, Chris and Jeff, and their construction worker buddy, Derik Nolan. Not even knowing what they were doing, they ran their little operation haphazardly, but over time they learned what the DEA looked for, when determining if a clinic could be busted for dispensing too many drugs. And they began implementing changes accordingly, until their company became a major player in the narcotic painkiller industry.

Astonishingly, though, when Chris George checked out the DEA’s own 2006 policy, he found that the federal agency would consider suspicious any doctor who “prescribes 1,600 [sixteen hundred] tablets per day of a schedule II opioid to a single patient,” Temple wrote. With numbers that high, it’s clear to see why the George brothers and Nolan thought they could get away with what they were doing.

American Pain is an important book about an epidemic that is far from over. Not only did Temple dig into the DEA’s own puzzling actions of allowing pharmaceutical firms to manufacture more pills than ever, but he did so while weaving together a powerful and sometimes even funny story about the three Florida construction workers who became so wealthy and powerful they were mafia bosses in their own right. Bosses the FBI brought down, when a female agent named Jennifer Turner took an interest in the construction workers’ clinics. Turner and her fellow agent, Kurt McKenzie, worked for more than a year to bring the case to trial. According to Temple, McKenzie says the only “other investigation that took the same toll on him . . . was the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.”

There is one other important thread Temple wove throughout his book: the victims of American Pain’s pill mill practices, many of whom died. Like the Racine, W.Va., man, who smashed his Camaro into a pickup truck while high on oxy. Or the Tennessee man who died in a Boca Raton motel, two days after being treated at one of American Pain’s clinic.

But Temple’s story about Stacy Mason, a young concrete worker from Kentucky who drove to Florida to get oxy so he could cope with back pain from a serious vehicle accident that made it impossible for him to work, will leave you longing for justice for all the victims of this terrible epidemic.

Many times, Temple got in his own car and drove up hollers in backwoods Kentucky to interview the Mason family for this book. Their story, like those of the other addicts Temple writes about, will make you angry that so many senseless deaths have occurred because of greedy pharmaceutical companies. Be prepared to settle in for a long read, because American Pain is an addictive read. And it will captivate you, making it almost impossible to put down.

* * * *

In November, I will have five books, Guilt by Matrimony, about the murder of Aspen socialite, Nancy Pfister. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and her memoir, Sister of Silence, placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

August 17, 2015

Mental Illness and Police Incompetence Lead to Murder, Suicide, in Aspen

Years ago when I published The Deputy for West Virginia police officers, a question arose about what would be considered newsworthy. At the time, the board of directors chose to let me have the final say over editorial content. When a fellow officer was later charged with DUI, I chose to put that information into the periodical. It wasn’t to make the officer look bad; it was to show that the group was transparent. That it wasn’t going to hide bad behavior or look the other way when it happened. That the members would be in the spotlight if they did bad, the same as if they did good.

Transparency–we need more of that now. I believe most American police officers are of high-caliber character: they won’t intentionally break the law, nor tacitly condone fellow officers who do. That said, we have a national problem: police officers who believe a badge gives them the power to use needless violence against others, prestige that places them above the law, and a position that renders them untouchable by fellow officers on the “thin blue line.”

In 1993, West Virginia Supreme Court Justice Robin Davis said an officer’s conduct is not just about transparency—it’s about appearances. Davis, then in private practice, was legal counsel for the West Virginia Deputy Sheriffs’ Association. During a board meeting I attended, she warned officers that their conduct better be spotless both in and out of uniform. Because people are watching.

Her comments occurred after a deputy sheriff in Kanawha County was fired for domestic violence. In the August 1993 issue of The Deputy, Davis said the fired deputy “inflicted minor injuries upon (his ex-girlfriend) and also damaged her vehicle,” when the woman repeatedly harassed his family.

This is a good time to consider Justice Davis’ words, in light of the recent incidents of excessive police violence—and officers who simply overstep their bounds or fudge the facts. It isn’t about race. It’s about doing the right thing, even when it’s not what you want to do.

My next book looks at a case of police incompetence that borders on criminal behavior. You won’t have heard about it, even though it’s been in the news repeatedly. Of course, the media got the story wrong. Hopefully next time, they’ll think twice about accepting as fact the statements they get from someone wearing a badge. Even if a person wearing a black robe has signed off on those statements.

This police misconduct may stem more from inexperience than malice, but the jury’s still out on that. I’ll let you readers decide. Regardless, people lost their freedom as a result, and lives were ruined. That’s not something that can be undone.

Two weeks ago, the man at the center of this case died. We had only met once. I spent eight hours with him inside Arrowhead Correctional Center in April, but I wish it had been longer. That I had known him longer. I wish I had met Dr. William “Trey” Styler before his depression changed him forever. In February 2014, not long after her body was found, Pitkin County police pegged Styler, his wife, and one other woman as the murdering trio who schemed to kill Aspen resident Nancy Pfister. They were arrested within days and spent more than three months in jail—until Trey Styler confessed.

Guilt by Matrimony: A Memoir of Love, Madness, and the Murder of Nancy Pfister was in its final stages when Styler hung himself in his jail cell on August 6, 2015. He was depressed and had been suicidal for years. His widow and I have slaved over this book, trying to be accurate and fair to both Styler and his victim. It’s been a balancing act of the most challenging kind. Two very sick people, both at risk, who ultimately harmed themselves far more than they hurt others.

I don’t write books about breezy topics that make for light reading. I write about real people with real problems; serious, even life-threatening problems. I’m fortunate that Trey’s widow, Nancy Styler, chose me to help write it–and then agreed to let me tell this story candidly. Of course, if she hadn’t, I wouldn’t have written it.

This book isn’t what either of us thought it would be at the outset. After my trip to Aspen in April, it morphed into something entirely different. I won’t give away all the details—but I’ll tell you that Aspen is no stranger to suicide. Which should have boded well for Trey and his wife, as well as Pfister. Instead, the people in Pitkin County, Colorado, ignored it, leading to two needless deaths. Not just one. And now we have a new ending, one that will surprise you. Then again, the entire book should, because it’s a far cry from the malarkey that’s been written about this crime.

I’ve given my full support to “the thin blue line” since I began reporting on cops and courts in 1988. Much to my regret, this book also reveals some pretty bad police and prosecutorial incompetence. Guilt by Matrimony reveals how the two, mental illness and police incompetence, played out in Pfister’s murder. It’s an important book. I hope you read it.

* * * *

In November, I will have five books, Guilt by Matrimony, about the murder of Aspen socialite, Nancy Pfister. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and her memoir, Sister of Silence, placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

August 10, 2015

From crippled to new knees in two months

It’s been three months since my last blog entry. That’s a long time in the world of blogging. Please forgive me. I didn’t mean for so much time to pass. And I admit, I’ve been negligent. I’ve also been a little tied up. Aside from trying to finish my fifth book, I now have two new knees. I call them bionic, but really they’re cobalt-chromium. It’s a bio-compatible metal, so I guess saying I have bionic knees is partially true.

I’ve wanted to dance, ballroom dance, for years. Now, at age 52, I finally will. And do Zumba and ride a bike and ice skate again. And squat to change a tire or get down on my hands and knees and scrub a floor, if need be. Most of all, I won’t have pain while walking or worry if my legs are going to give out while climbing stairs.

Surgery morning: Martha, my surgical nurse, and I met in 1983. Surgery day suddenly became a reunion for us both.

In 2004, the most conservative orthopedic surgeon in Morgantown told me I had the knees of a 60-year-old. “You need new knees,” he said, and then told me to put off surgery as long as possible. I did. I waited 11 more years. Then this January, I learned that my knees weren’t, as that surgeon said, full of arthritis. I was born this way. “If they catch it when you’re a teen, they can do corrective surgery,” Dr. David Tuel, an orthopedic surgeon, told me. “If not, you have a lifetime of pain.”

That sure was true. So surgery was scheduled, then rescheduled, then finally the big day arrived: May 20. The surgery itself was easy; four hours after going under the power saw (Yes, Virginia, doctors really do use power tools when replacing your joints.) I was recovering in my Garrett Memorial Hospital room in Oakland, Md.

Dr. David Tuel replaces the bandages on my legs.

But the rest was no fun. In fact, it was one of the most painful experiences ever. Worse than childbirth—and this from a woman whose three out of four deliveries required no medication. Including my last child, who weighed a whopping 10 pounds!

Not so much my bilateral knee surgery. I took every hit of morphine I could. Later, a friend said he taped the button down so he didn’t have to keep pushing it every 10 minutes. I should have thought of that—because sometimes I dozed off or got caught up in the moment, and then the pain ran full steam ahead of me.

Dr. Tuel ordered physical therapy the day after surgery. If I had not lived to tell the tale, I wouldn’t have believed it possible. But I did. On May 21, I stood for the first time. Human assistance came at every step along the way, including swinging both my legs out of bed and onto the floor. Ditto for back into bed. It was a humbling experience. One that taught me what I was made of.

From the nurses who saw me hobbling down the hallway with my walker, to the physical therapists who saw me walking without it a week after being transferred to Heartland in Kingwood, W.Va., for rehab, everyone remarked they’d never seen such progress in a bilateral knee patient. Throughout, they were amazed. Apparently I was doing what many patients with only one new knee couldn’t do. I know much of what I accomplished came about because my surgeon did an excellent job. If he hadn’t, I would have had setbacks. But the medical staff and my great team of physical therapists told me it was my determination to become mobile again, to be totally independent, that inspired such great progress.

There was one small problem following surgery. Due to losing a good bit of blood afterward, I became anemic. By then, even if the morphine hadn’t made me speak and write gibberish, the loss of blood certainly did. Because I follow the Bible’s admonition about the sanctity of blood, I don’t take blood transfusions, so that wasn’t an option. What I requested, and received, were all the additional medical procedures that would help rebuild my low blood supply: iron infusions, folic acid, and liquid chlorophyll, among other things. The medical staff at both Garrett Memorial and Heartland went above and beyond, even consulting with the bloodless medical team at Johns Hopkins Hospital, to ensure they gave me what I needed. The protocol worked so well, in fact, that one month after surgery, my primary care doctor asked me how my hemoglobin (that’s the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen) went from six to eleven so quickly.

Having spent much of my life in Preston County, I have to say my Heartland stay was like a homecoming of sorts. I wasn’t sure if I would know anyone—or if anyone there would know (or remember) me from my days at the Preston County Journal. Or remember my Vintage Berry Wine columns. Or if anyone there had read my books. I quickly learned I knew several people there, patients and the people who visited them. Turns out, Heartland is a great place for a family reunion of sorts. Some people even make weekly visits, since so many of their friends now live there.

James was my primary therapist at Heartland. The first time he worked on me, I cried. Later I appreciated how hard he made me work.

Most of the staff didn’t make the connection about me until I was almost ready to leave. Even then, they did so in large part because they had heard about a local story, Pretty Little Killers. But some of the female staffers had heard about my memoir, Sister of Silence.

Being a writer isn’t as glamorous a job as many people believe. It’s hard work, long hours, and low pay. Not too many of us can claim to make a six-figure income. If you write nonfiction, like me, it’s even harder. There’s digging to do and facts to check, and at times, the writing process can be quite tedious.

Nonetheless, the reward that goes far beyond monetary happens when someone who has read your book literally cannot stop talking about how much they love what you wrote. How they hadn’t read a book in 10 years. Or how your book kept them reading in one long sitting, until 3 a.m., when they wanted to pick up the phone and call you to ask you all kinds of questions.

I mention that because after I left Heartland, someone else there who later read SOS wrote to me. “Now I know where the strength to have both knees replaced at the same time came from,” she said.

My dear friend Susan drove all the way from the Huntington, W.Va., area to take care of me.

Yes, but still, I could never have accomplished it without the wonderful caretakers who helped me heal. I received top-notch care from everyone, from Dr. Tuel (who cut his Memorial Day weekend short so he could return to check on me) to the entire staff at Heartland.

Then there was you. Many of my reader friends followed my progress from surgery to rehab to home. You cheered me on from near and far, sent cards, and inspired me to keep going. Some of you even came to see me, including one dear friend who drove three hours to help take care of me.

You were the best medicine of all. Thank you!

* * *

In November, I will have five books, Guilt by Matrimony, about the murder of Aspen socialite, Nancy Pfister. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and her memoir, Sister of Silence, placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

May 2, 2015

I’m White, But I Wish I Had Been #momoftheyear

I am a white woman but I’ve wished more times than I can count that I had been #momoftheyear. That’s because Toya Graham, who can now add that hashtag to her bio—and my black female friends—disciplined their children in such a way that their offspring knew better than to misbehave. Or else. It wasn’t that their mamas meted out abuse; it was just that those black women didn’t take any sass from their kids. Had their children even tried, they would have found themselves on the receiving end of a smack across the mouth, their bare bottom bent over a knee, facing a whipping with a belt.

So why, I’ve asked myself, did I get so upset when I saw video footage of the now famous Baltimore mom smacking and swearing at her teenage son, Michael Singleton, earlier this week? I posted on Facebook that Michael probably wouldn’t have been involved in the riot if not for the violence he surely learned at home. Violence I thought Graham probably dished out even worse in private. But in the days since I posted that, and after seeing Graham’s interview on national TV, I’ve given it a lot of thought—and realize I was wrong.

It’s not something I would have done—but then, maybe I never would have needed to: my only son is white. So we never had “the talk,” that preventative, protective chat that black parents all around this country recite to their teenage sons when they come of age. I’m sure Toya and Michael had the talk years ago because for her, the fear that her black son could be killed by a police officer is very real. And I certainly have no idea what that fear feels like.

It’s a moot point whether Graham “lost it,” as she says, because she was afraid Michael would be killed for throwing a brick at a police officer, or because he could become a casualty at the hands of a fellow rioter. What is important is how she acted like a mother bear when she saw her son in harm’s way. The fact that he put himself there is irrelevant.

Or is it? Graham warned Michael not to get involved in the riot. Many mothers—white and black—commented on my Facebook thread, saying if their child disobeyed their orders to stay away from a riot, they would have done the same thing she did.

Their comments made me question my own views, and the way Toya parented her son in public. They took me back to 1990, shortly after I fled my abusive white husband. One day I was so frustrated by the fact that he continued to manipulate my children, just as he kept psychologically battering me, that I inflicted my own pain on my daughter, Jocelyn. She was nine, and threw such a fit that I took a switch to her backside. I left bruises. It is the only time I ever remember losing control like that.

My own actions that day hindered my ability to use corporal punishment on my children forever after. I tried to occasionally, but only if I knew I wasn’t angry, so I wouldn’t repeat that terrible mistake of 1990. But mostly I used time-outs, or made them write sentences, or took away their TV-watching privileges. By the time their father decided he wanted to try to be a real dad and sued me for custody, he had been sabotaging my own parenting for years. (His parenting experiment failed miserably, since Child Protective Services intervened in 1999 when he and his second wife abused two of my daughters so badly they were removed from his home.)

You see, long before my children became teenagers, the man who had punched holes in our walls and trashed our furniture told them if I tried to discipline them, they could call 911 for help. In so doing, he essentially handicapped me as a mother, and prevented me from disciplining them—all while he continued terrorizing them during their weekend visits to his home.

However, if I had been a black woman, I wouldn’t have let his attempts to undermine my parenting stop me from doing what I knew was best for my children—and I feel certain they would respect me more today, as a result.

Graham’s actions have certainly earned her respect from many other people, that’s for sure. Chuck Yocum, a Baltimore area parent and educator, was watching the riots unfold on TV not far from his home when he wondered where all the parents were.

“Then, there she was, doing what every parent watching said they’d do,” Yocum said. “She represented hope. Hope that other parents might do the same thing yes, but in a larger sense, hope that Baltimore may not be totally lost after all. There are still parents who care about their kids.”

Graham’s desire to save her son comes at a time when people are saying this country’s race riots are starting all over again. When, depending on what neighborhood you’re in, it’s dangerous to be a black man. Or a white cop. When police have become cynical about black men with rap sheets, and when they arrest first and ask questions later—as apparently happened with Freddie Gray.

I worked with law enforcement from 1991-96, writing police journals for the West Virginia Deputy Sheriff’s Association and the West Virginia Fraternal Order of Police. Most of the men and women I rubbed shoulders with were white. Most of them—but not all—were good officers, who would never intentionally harm anyone simply because of his race. Like my friend K.C. Bohrer, an officer whose conduct has always been unimpeachable and who can’t forget the murder of a West Virginia teenager. Who would like nothing more than to see that girl get justice, even though she’s been dead for more than thirty years.

Some of the officers I know have also worked in big cities where they see blacks killing blacks, and where they know that many black youth have no hope. Most of these (predominantly white) officers are just as saddened by that as are the parents of these black teens.

Whenever I think about the growing divide between white and black, I remember my friend Paul. He was black. When I was twelve, he gave me my first kiss. Two years my senior, Paul was going places. He was intelligent, handsome, and—even more important—he was from a law-abiding family who reared their black sons to treat women with kindness and respect. Who instilled in those sons a healthy fear of displeasing not only their parents but other authority figures.

Paul and his brothers were the kind of boys who grew into men who would never dream of calling me anything other than “Ms. Berry,” because they were so well trained. I know that, because every so often I gently chide them to use my first name. “My mama would throw a fit if I did,” they say, laughing.

And still, in spite of the stellar parental training my friend Paul received at home, something went wrong.

As childhood crushes go, ours lasted for all of a minute. But I never forgot him and I still remember the shock, anger and heartbreak I felt for Paul and his family, when I learned he had been in the wrong place at the wrong time, when he witnessed a felony that landed him in jail after being charged as an accessory to a deadly crime.

I don’t know how or why Paul ended up rubbing shoulders with thugs, but while he was doing that, I was working with the cops. And every April my job took me to Washington, D.C., for National Police Week, where I interacted with dozens of officers and mingled with hundreds more.

That’s how I came to be in Alexandria, Virginia, one warm spring evening in 1994. As I hurried along the sidewalk to meet my friend Ruth, a young widow whose Hispanic husband was slain in the line of duty, I saw three older black teens coming toward me. They walked side by side, and showed no sign of moving over. So I moved, but apparently not enough. The teenager closest to me brushed my shoulder, jarring me. I kept walking. I didn’t look back.

That moment is etched in my memory to this day, because of what I saw in that boy’s eyes: it was anger. Or hate. Most likely because he saw only a white woman, and nothing else. Probably because he believed I was affluent, since Alexandria is home to the wealthy. Possibly because he had no hope of being able to ever eat at the restaurant where I was going to dine.

What he couldn’t know is that without the FOP picking up my tab, I couldn’t have paid for the gas to drive to D.C., much less a dinner there. As a single mother of four children, we had only recently given up our food stamps. And at that time my children still qualified for a medical card. That black teen could not have known this. The only thing he knew for sure was that I was white. In his mind, my skin color gave me privileges he would never have. It identified me as the enemy, along with the people who had enslaved his people. That was enough to make him angry.

The next morning at breakfast I told an officer I was having breakfast with what had happened, asking what it meant. “It’s a good thing you kept walking and didn’t make a fuss,” he said, and then implied I could have been killed. “Here in D.C., black boys know they have nothing to live for, that they’re most likely going to be dead by the time they reach eighteen.” At the time, he was talking about gangs.

Twenty years later, his words still haunt me. That sole conversation with a white police officer, borne from a single chilling encounter with three black teenagers, comes back to me every time I hear about another black teen being killed—whether his death came at the hands of a police officer or a gang banger.

Those words returned to me again yesterday, after reading them online. Except this time they were spoken by a black woman. “These kids have no hope,” Erica Garner said on CNN. (Garner is the daughter of Eric Garner, a New York man who died while in police custody.)

I’m a white woman and I agree: many blacks have no hope. They live in ghettos and other poor neighborhoods, like those in Baltimore, Md., and West Oakland, Calif., places where food deserts thrive. A food desert means the people of color living there have virtually no access to healthy food—but with more than 40 liquor stores in the West Oakland area, they do have access to alcohol and tobacco. And processed or junk food. This is just as true for some areas of Baltimore.

I lived in Oakland in 2009, where I gained an eye-opening education from my daughter, Jocelyn, who told me how hard it is for people of color to buy good food. That’s because there are few, if any, real grocery stores in many poor neighborhoods. In West Oakland, the average income is $21,124 per year, and 32-percent of the residents live below the poverty level. The lack of access to good food leads to other problems, such as health and behavioral issues. I learned this in my own home, when my children were preschool age or younger. They had never eaten sugar—until both sets of grandparents gave it to them. I noticed a direct correlation between the sugar-sweetened cereal my mother fed them and their behavior. I quickly learned to limit their sugar intake, which is one reason we rarely had soda pop or processed sweets in our home.

Years later, my daughter Jocelyn has made it her mission to help disadvantaged black families around the country, doing so in New Orleans (she sold her car and relocated to help Hurricane Katrina victims), Chicago (where she began a recycling program that’s still in place several years later), and Pittsburgh (where she discovered that many blacks cannot afford to buy the monthly bus passes necessary to gain a good education or employment), taught me why black youth are so hopeless. Much of it has nothing to do with the police but rather, with the lack of access to basic necessities that white people like me take for granted. Or like I used to—before working in and walking the streets nearby West Oakland.

Whether it’s danger from not having good food or from jaded, uncaring police officers, Toya Graham didn’t want her son to end up like my friend Paul—or worse. And she had the backbone to follow through, giving her son Michael a badly needed dose of tough love. It’s something I now believe many of us white mothers can learn from.

* * *

I have four books, and am currently writing my fifth, Guilt by Matrimony, about the murder of Aspen socialite, Nancy Pfister. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and her memoir, Sister of Silence, placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

March 23, 2015

Black or White, Martese Johnson, Elizabeth Daly, Hannah Graham All Harmed in Charlottesville

As I packed my bags for the Virginia Festival of the Book last week, I thought about Hannah Graham. The pretty, freckled 18-year-old University of Virginia student was abducted and murdered last September. Graham has been on my mind since I first heard she was missing, so I wanted to retrace her final steps while I was in Charlottesville. I wanted a way to honor her, and to reflect on the dangers fraught for female college students these days. I didn’t expect to learn so much when I did so.

Hannah Graham (courtesy of c-ville)

I had no idea until I stepped onto the Downtown Mall in Charlottesville how upscale a neighborhood Graham was in when she disappeared. Or, as one resident told me, why Graham wouldn’t have been inside Tempo, the 5th Street SE restaurant where she was supposedly seen for the last time on Sept. 13, 2014. Where the news media camped outside its doors for the next few weeks, as eager for scraps of information as a passing canine would be for leftover beef ribeye scraps.

More important and certainly more unsettling, I learned why Graham’s alleged killer, Jesse Leroy Matthew Jr., would not have been inside Tempo with her. It’s something I haven’t seen in the media, and I’m wondering why reporters are keeping it quiet. Especially the local media, whose connections with townspeople and business owners surely offer them better access to the truth than any big-city reporters. I suppose they really might not know, but that seems a little farfetched.

I was sitting inside Tempo sipping an espresso martini Thursday after listening to Lucinda Franks talk about her marriage to Robert Morgenthau, as part of the panel discussion, “Lives, Loves, and Literature.” A few feet away, a live press conference was taking place. For a crime reporter, there is nothing quite like finding yourself smack dab in the middle of a breaking story that becomes national news. For this crime reporter, who has become very saddened by how badly decent black men who are not criminals are treated, I was glad to be discussing writing and books with a young couple seated at the bar next to me, instead of becoming sadder still, as I’m sure I would have had I attended the press conference.

At the heart of the event was what really happened to Martese Johnson, the 20-year-old black UVA honors student who was thrown to the ground by Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC) agents a day earlier, after they claimed he was causing a disturbance. (Witnesses and even the bar owner where Johnson was denied entry say he wasn’t.) What really happened matters, you see, because Johnson was left very bloodied, with a head injury, and 10 stitches to close the gash the agents gave him when they threw him to the ground.

Martese Johnson (courtesy of ABC)

I can’t speak to that incident, but other Charlottesville residents can. “They’re the worst,” one older (white) shop owner said, comparing the ABC agents to thugs. A black engineer I talked to during my four-day stay said race isn’t a factor. Then he told me about Elizabeth Daly, whom ABC agents harassed in 2013 when they thought she was buying alcohol. (It was sparkling water.) Daly was then 20, and also a UVA student.

According to Reuters, “Daly, who is white, filed a $40 million lawsuit, which the state attorney general’s office eventually settled for $212,000.”

Elizabeth Daly (courtesy of NewsPlex.com)

Suffice to say the agency has given itself a very black eye, and this week some federal officials are calling for it to be stripped of its powers. Given how reckless its agents are, is it any wonder?

With the media focus on Martese Johnson, it might be easy to forget about Hannah Graham. But I can’t. In large part because Hannah might still be alive, if not for the fact that local authorities apparently missed the clues so many people saw in Matthews’ odd behavior, down through the years.

For example, I was told that Matthews, who has a lower-than-normal IQ, was regularly refused entry at several local bars. Why would that be? Well, Matthews would show up late at night and try to hit on young, drunk, female college students. No wonder police believe they might have a serial rapist on their hands.

Word got around about Matthews’ tactics, so he was blacklisted from many of the local establishments that serve alcohol. One of which was . . . Tempo.

Speaking of Tempo, it’s a pricey place that serves duck and a clientele of “rich white men,” as one resident told me. Which is why I chose to go inside for a drink, to see for myself. Yep, it sure is. I can’t imagine it being a favored hangout for many—if any—college students. Graham, I am told, was turned away at the door, because she was underage.

And that’s where it seems Matthews found her. He escorted her around the corner, into his car, and . . . that’s the last anyone saw of Hannah Graham.

Matthews—who comes from a well-respected family—has known anger issues. But he is also said to be so nice to some small children he knows well that they couldn’t believe he was possibly connected to Graham’s disappearance—was once asked about his late-night bar tactic. “It levels the playing field,” he supposedly said.

Well, not for Hannah Graham.

* * *

I have four books. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and her memoir, Sister of Silence, placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

February 27, 2015

West Virginia Author Seeks Help Finding Trilogy, Her Timid and Temperamental Cat

Three weeks ago I was preparing for vacation when my daughter Courtney dropped by. She had agreed to watch my baby while I was gone. “I’ll keep her in my office,” she said. “There’s no other animals in there, so she’ll be fine.”

My baby, nine weeks old

Trilogy is almost two. I fell in love with the furry ball of tricolor fluff when I saw her Facebook photo, posted after she was dumped along the side of the road from a cooler. I got her from P.U.R.R. right after she’d been spayed and micro-chipped. She was nine-weeks-old. Trilogy was rarely exposed to people’s pets—so she doesn’t much like other animals. She’s been an indoor cat since then. The wildest creatures she’s ever seen are those pesky stink bugs that find their way into every home on the East Coast. Kept indoors to protect her from fleas, feline leukemia, and errant cars, she’s calico in color and temperamental in nature, and usually only allows two people to pet her. I love being one of them.

I learned about the fire Saturday when Courtney told me that she and her family came home from dinner Friday night to find flames dancing against the night sky—and inside their house; how she unsuccessfully hunted for Trilogy; how the fire department volunteers fought and finally extinguished the blaze; how she left her office door ajar, in case Trilogy came out of hiding and needed an escape; how the fire later rekindled, burning down what was left of their home; how the room where Trilogy had been was, by then, no more than ashes.

She apologized. I told her it was okay. I was simply glad she, her husband, my grandson, were all safe. Then I went to my book signing at The Market Common Barnes and Noble. The next morning my friend and I cut our trip short and headed home. That was Sunday and after several Facebook friends suggested doing so, Courtney said she would set a live trap in case Trilogy did escape. Without saying why, I asked for a photo when she did.

Uh, no, she didn’t exactly like her regular vet trips, which included being spayed and micro-chipped as a kitten.

When I arrived back in Morgantown early Monday afternoon, a family member accused me of only wanting cat-trap pictures “for my audience.” Which was more than a tad unfair. First, I don’t feel like I have an audience. I have readers—readers who are my friends—and friends who are my readers. And although I grew up in rural Preston County, where I chopped wood and carried far more than my fair share of coal in those old rusty, five-gallon buckets, I wasn’t and never have been a farm girl. I am, though, a visual person who likes to see objects so I can fix them in my mind—especially ones I’ve never seen. (Until Tuesday, when I saw an online photo of a live trap, used to catch feral cats.)

With all the talk about setting live traps, all I could see, in my mind’s eye, was my six-year-old self, watching a cardboard box with a string tied to one end, propped up on its side under a tall pine tree after I begged my dad to catch a bird I saw hopping around. (I caught the bird, too, much to my delight and my dad’s surprise.)

As most cat owners know, the best “trap” for a cat is a brown paper bag. It was the sight of a bag that brought me to tears—an empty Cracker Barrel bag lying on my dining room floor that Trilogy often played with. Heartbroken, I cried for two hours Monday, as I thought about the cat who would jump all over a room, trying to catch sunbeams or houseflies, if they were about; who loved putting her paws up on the edge of the bathtub while I bathed, or vaulting herself from the toilet onto the sink to watch me in the water, as she seemed to contemplate jumping in herself; who never, ever missed the litter box unless she was sick; who would occasionally drape herself on my desk, her legendary long whiskers or bushy tail trailing onto my keyboard as I tried to type; who could jump halfway up a door to try and catch those little red laser beams I loved teasing her with, and who made me laugh with wonder when she turned over on the floor like a dog, paws in the air, waiting for my foot to rub her exposed belly.

I woke up ill Saturday morning and the two-day drive home from vacation was exhausting, so I practically slept from Monday night until Wednesday. Didn’t go outside until that afternoon, when a friend drove me south, down Bird’s Creek Road to Route 92, then left onto Route 50 east, where I hoped I could somehow entice Trilogy to come out of hiding. York Run Road, a narrow country lane at best, was passable, but still had mounds of snow piled up along its edges. And Courtney’s place was nothing but a sheet of ice, made so by the gallons and gallons of water from the firefighters. Courtney showed us where to place the items I brought along: some canned cat food, a shirt I slept in, and a container full of liquid.

We walked carefully to the handicap ramp that once led to the front porch. Built for my 14-year-old grandson, Grizzly, who defies that term in every way, the ramp remained intact in spite of the fire. I opened the lid of the Betty Crocker plastic can. Looked at the yellow liquid inside. For once I was glad my sinus infection had rendered me unable to smell. Unlike my cat, I hoped. Someone told me, you see, of lost dogs who made their way home after their owners left some of their own urine in a trail of sorts for the canines to find. Since Trilogy’s home was in Morgantown an hour away, and because she had never been to Courtney’s home before, she would need my scent to help her find her way. That’s what we surmised, anyway.

So before my friend picked me up, I peed into the frosting container and poured a little on the blue shirt, just in case, packing it all up in a sack. There was more than enough of my pee to cover a small patch of grass under the ramp, so if Trilogy was nearby, she had to recognize my scent. I hoped. Then I opened some canned cat food and left it on the blue shirt for her.

After I returned home Wednesday afternoon, I saw icicles creating a translucent crystal sculpture as they spiraled down into a black hole. It was the best shot ever and when I looked through my iPhone lens, Trilogy, my bashful calico cat, appeared in the hole, clawing her way up the ice. I dropped my phone and began chasing Trilogy on the ice-covered ground.

Maybe she will pick up my scent and find her way home, an hour away.

That’s when I opened my eyes—to the wide-awake reminder that finding Trilogy was no more than a leftover remnant of my nap. But that’s what made me return to York Run Road yesterday, where I drove along about 12 miles an hour, three miles up and three miles back, windows full down, heat set on high. “Here Trilogy, here Trilogy, kitty, kitty, kitty,” I called. All the way up. All the way back. Stopping every now and then and hoping that maybe, just maybe, I would see her come running in my rearview mirror.

I don’t give up easily. After all the amazing stories I’ve heard this week of lost and injured pets that make their way back to loved ones, I have to believe Trilogy will return home. Maybe, like that stray cat in the movie Sweet Home Alabama, a little singed and worse for the wear, but ready for her next life.

* * *

NOTE: Trilogy went missing from York Run Road, between Newburg and Fellowsville, in Preston County, W.Va., but she lives in the Greenbag Road area of Morgantown, near Sabraton, so she may show up anywhere along the way. This includes Route 119, the Kingwood Pike (near her vet, Dr. James Minger), the Gladesville Road, or even Route 7. I am happily offering a reward for her return.

* * *

I have four books. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and her memoir, Sister of Silence, placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

January 14, 2015

It’s Cold Out There—So if You’re a Tenant Know Your Rights

Welcome to winter in all its glory: snow and ice and subzero temperatures when the wind chill decides to kick in, as it did most of the last week—and as it’s sure to do again. Accompanying these feats of the elements are frozen pipes and broken furnaces or, if you live in an old, drafty house, the need to hang blankets from doorways and use a blow dryer to adhere plastic to your windows. Otherwise, all your heat will escape even if the wood stove or fireplace is in good working order.

“Fine,” you say, “but tell that to my landlord. He’s threatening to evict me if I don’t pay my rent—and I won’t pay it because I’ve been without water for a week and haven’t had heat in three days. I finally bundled up my kids and took them to my mother’s, after my three-year-old came down with pneumonia from being in a cold apartment.”

I read an email quite like this one recently, from a single parent I’ll call “Jane” in West Virginia. Jane read my memoir and wondered if I had any suggestions. As I typed my reply, 25-year-old memories as fresh as yesterday jumped to the forefront of my mind.

I was then a 28-year-old single mother myself, confronting a different water problem: sometimes it came out of the spigot an ugly orange, other times a brackish shade. No matter the hue, it always smelled like rotten eggs. The worst part, however, was that it ruined our clothing.

The landlord told me, in essence, to live with it.

Right! You try carting dirty clothes for a family of five while simultaneously dragging four little ones into a laundromat and see how much fun it is—especially when four of the five are age 10 and younger. And that doesn’t even count my financial outlay, which cut into my already meager income.

Instead, I withheld rent and sued him in magistrate court—where I won, because tenants have something called “rights.” They are very similar to employee rights, in the sense that tenants cannot sign them away.

What does that mean? Just this: even if you signed a lease that says, in effect, “The wiring is bad but if the house burns down, you have to pay the landlord for the damages,” the law will not hold you responsible. Essentially, that portion of the contract is null and void, even if you signed it.

Clearly, I am exaggerating. But you get the point: a landlord can’t write up a lease that holds you responsible for his putting you up in a place that could essentially be a firetrap.

I guess I should give you this quick disclaimer: I am not an attorney. (Although I did sign up to take the LSAT once.) I am merely an author, who happens to know her rights as a tenant. That’s because I love doing research, so when I grew frustrated with my landlord, I began digging away at the library (Remember, this was before the Internet, folks.), until I came up with the state code for West Virginia. And there it was, in Chapter 37, Article 6, in bolded letters: “§37-6-30. Landlord to deliver premises; duty to maintain premises in fit and habitable condition.”

The longer I read, the more excited I became because, guess what? Landlords can get away with a lot, but not as much as they often lead you, the tenant, to believe. In fact, the law frowns on landlords who let tenants live in unsafe or uninhabitable (meaning it isn’t comfortable or clean enough to live in) buildings. West Virginia state law says as much, as I’m sure every other state in the country does. (In Massachusetts, the law even stipulates that during winter the heat inside a rental property can be no less than something like 68-degrees.)

States do this to protect us, people who are consumers, because if they didn’t, many bad landlords would do whatever they want, without fear of reprisal, and their tenants would be stuck. States also do this because safety is a basic human right. If you are without heat or water, your rights are being violated.

That being said, you don’t need an attorney if you are living in a place that is unsafe or unsanitary. You just need to know your rights.

So let’s say you’re like Jane, who has been without water for a week, and heat almost as long. And to make it even more exciting, let’s say you, again like Jane, refuse to pay rent until your landlord fixes the problems. Of course, your landlord, great guy (or gal) that he is, might threaten to evict you. What do you do?

You could use the money you would have paid for rent to pay a plumber or electrician, to fix the problems. Then you present the landlord with copies of those expenses, by way of an explanation for where your rent money went.

You can also head down to your local court. Here in West Virginia, that’s magistrate court. There you ask to file paperwork charging your landlord with neglect and endangerment. (If you don’t have much income, they will even waive the filing fee, so don’t forget to ask about that, too.) And please, consider citing a financial number if you feel he owes you for damages. For instance, Jane would include the amount of her child’s hospital bill, lost wages if she had to miss work due to the landlord’s negligence, and, if she paid someone to repair the furnace, she should include that amount, too.

To do this, you must keep copies of the receipts showing those expenses were legitimate. It’s also important to document any phone calls to and from your landlord, any professionals you hired to fix the problems, and anything in writing (Please, put all correspondence with your landlord in writing, such as an email, so you have a paper trail showing you notified him of the problem!) that shows you’ve done your part, but the landlord simply refuses to do his. Which means you had no choice but to take matters into your own hands.

Yes, your landlord may try to evict you. He may even succeed, eventually. But the law is on your side—even more so if you have children or someone with a serious medical condition living in your home. Here’s the real kicker, though: if you refuse to pay rent because of a serious problem and/or you file a complaint about your landlord and he threatens eviction, that’s called retaliation. It’s illegal in most states, and your state attorney general’s office would love to hear about it.

To be on the safe side, though, it would not hurt to keep your eyes open for a better place with a better landlord, so that if and when you are evicted, you don’t have to go live with Aunt Bessie or sleep in your car. (Trust me, if you have little ones, sleeping in your car will make hades look like a cool dip in the pool. Don’t even try it, especially in wintertime.)

Throughout all your interactions, your landlord may get ugly, but that doesn’t mean you have to. Maintain a professional, courteous tone of voice at all times—even if, like Jane, you could scream because your three-year-old’s coughing is so bad you’re afraid the child’s going to die. Trust me, having your blood pressure rise out of control will only make you feel worse.

Finally, most landlords don’t want to go to court any more than you do, so sometimes all it takes is politely telling your landlord (again, in writing) you know the law requires he fix any serious problem such as being without heat or water. Then ask him to do this, and say what you will do if he refuses to act.

In the end, that’s the best way to handle it. But if you’ve got a stubborn landlord, sometimes going to court—or at least filing a complaint—is your only option.

* * *

I have four books. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and Sister of Silence placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

January 1, 2015

Pen in Hand, I Begin 2015 By Looking Back at 2014

I do so because I believe Pearl Buck’s words: “To understand today, you have to search yesterday.”

Searching yesterday, as in all of 2014, I found that I’d forgotten about some celebrity deaths, undoubtedly because I’ve been more concerned about the ones here at home. Still, they lived, they entertained and inspired us, and in 2014 Maya Angelou, Robin Williams, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Mickey Rooney, Lauren Bacall, Shirley Temple, and many others all died. Some of them, like Hoffman and Williams, died far too young.

I’m starting 2015 by looking through all these scraps of paper, sorting and filing what I need and tossing the rest.

Personally, I was touched more by Maya Angelou and Robin Williams’s deaths than the rest, because their own work touched my life profoundly. In their collective body of work, they speak to the human condition—a topic Angelou always talked about, and something Williams taught me with his many roles.

As we start 2015, the world is a hot mess. Here in the U.S. by the men in blue have led to riots over race, privilege, police, deadly force and justice. Or, some say, the lack thereof. Then there was the University of Virginia gang rape that was—and then wasn’t. Or was it? From kindergarten to college (43 in Mexico, 276 in Nigeria, and 132 in Pakistan) at least 451 students were kidnapped and/or murdered. U.S. and U.K. journalists were beheaded. And three Malaysian airliners have crashed: one simply vanished; another was blown from the sky by a drone, and the most recent one appears to have been downed by a bad storm.

Those were some of the more sobering headlines that found their way onto the 27/7 news cycle, and which caused not a few people to give up reading or watching the news completely. Then there was less important news, which quickly turned quite serious. For instance, there was the parody about a plot to murder North Korea’s leader. That seems to have led to a cyber-attack on Sony (the debate continues as to who was responsible), one of the largest movie studios out there, which resulted in dozens of embarrassed celebrities. Not to mention studio execs, after the hackers shared email correspondence and other private information with a voyeur public.

Along the way, free speech was taken hostage—until President Obama reminded his people that the United States does not cower before cowards, resulting in said speech being released, to the tune of almost $20 million in earnings for Sony after just one week.

Another disturbing 2014 news story involves the rise of the dangerous group ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), not to be confused with that other Isis, the ancient Egyptian goddess of health, marriage and wisdom who surely must have been much more benevolent than this modern ISIS. On top of that danger, there was the equally deadly Ebola outbreak, which killed more than 7,000 people in West Africa, and made even me worry about boarding my next flight.

The Ray Rice elevator incident, and the two-steps-forward-one-step-back dance the NFL took in response—all of which has served as the best campaign against domestic violence in decades—made for a fascinating 2014 news story. By punching out his then-fiancée (now wife) the former Baltimore Ravens running back has provided a new level of awareness to the behind-closed-doors war zone that many women and children have remained captive to for far too long. If Twitter is anything to judge by, (#WhyIStayed) the clumsy Rice-NFL mambo has helped other men learn that women aren’t punching bags. Or footballs, to be kicked around. But there is a price to pay for doing so—which can include losing your job as a breadwinner.

Then, most recently, a bit of good news: U.S.-Cuba relations saw a thaw, which means it’s only a matter of time before the island and its archipelagos become yet another pit stop for cruising tourists. Oh yes, the thaw also means that authentic Cuban fare should be much more accessible to people like me, who find their rich blend of exotic spices a culinary delight to the palate.

One of the best feel-good stories of 2014, perhaps by now forgotten in view of the overwhelmingly bad news, is the one about Pakistan teenager Malala Yousafzai, who in 2014 was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for her “struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education.” At 17, she is the youngest person to ever receive the distinguished prize. This and Malal’s own bravery at age 15—when she single-handedly stood up to the Taliban—reminds us that while courage often comes in the face of a child, it can flee by the time we become adults. (Then again, all those nurses and doctors caring for Ebola patients give us faith that even adults can be courageous when they are called to do so.)

Here in West Virginia we were happy to see a corrupt coal baron indicted in 2014 for his part in the Massey Energy deaths of 29 miners at the Upper Big Branch Mine four years ago. Yes, Don Blankenship will have his day in court, for putting insanely rich profits before the safety of his employees. I’m just happy that the winds of change seem to be blowing in our direction over here in Appalachia, hopefully bringing down the Dark Lord of Coal Country with them.

I’d like to think this constitutes a happy change here in Almost Heaven, since the ongoing fallout for company execs at Freedom Industries includes similar federal charges. That firm, you might recall, contaminated drinking water for 300,000 residents one year ago January 9 when MCHM, a toxic chemical, leaked into the Elk River, leaving many people without a way to even take a bath—much less a drink.

And even closer to home, here in Morgantown, W.Va., the Skylar Neese murder case came away as one of the top five biggest news stories in 2014, according to WDTV. It was a real downer, and I should know, because I covered the story on my blog while simultaneously writing two books about the case and its related legal proceedings. (But make no mistake, although some of the details from my blog were used in the book, less than one percent made it into Pretty Little Killers.) If you aren’t familiar with the tragedy, it will air January 3 on ABC’s 20/20—just two days away. The adorable Ryan Smith asks some great questions during his interview with my coauthor and me.

The first book about the case, an ebook titled The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese, contributed to my becoming a New York Times best-selling author–which was definitely the most unexpected good news I personally got in 2014. Having this title added to my résumé was not something I aspired to–because I never sought recognition for my work. My work involves shining the light on other people, so journalism used to mean working behind the scenes. Not being the story. But I do believe that when you work hard, and you do good work, recognition comes whether you seek it or not.

Being a reporter, or a journalist, aren’t always one and the same—especially nowadays. Reporters report; journalists dig and dig, unearthing facts some people would rather keep buried. That being said, I have wonderful colleagues who refuse to be called “journalists” because they believe the title has become synonymous with reporters who feel entitled.

I don’t as a rule make New Year’s resolutions. I resolve every day when I get up to try and make that day better than the last. Some days I succeed. Other days I fail. In an epic way—but I never give up trying.

So for today, be it January 1 or not, I have concluded the following while looking back at the last year: I will post more about my work to social media, and I will blog once a week. I might blog here or at Huffington Post, depending on what news stories are making the rounds that week.

I would like to take in a professional journalism conference this year, to help me hone my writing, editing and cognitive skills. I also need to be kinder to myself, as I continue trying to find a good work-home-personal life balance.

I resolve to go through scraps, one at a time, and toss or file, and I’ll do the same with clothes I’ve outgrown or those which are heaped up in a mending pile, and with the books I’m never going to read. I’m also going to worry less, and to remember more, including this key point: “Poor planning on your part does not constitute an emergency on my part.”

Oh yes, and I will finish my sequel, To Shatter the Silence–sooner rather than later. Come downed aircraft, pestilence and disease, or other tragic world events that are sure to happen this year. All the while hoping that only good things light up our lives in 2015.

* * *

I have four books. My memoir, Sister of Silence, is about surviving domestic violence and how journalism helped free me; Cheatin’ Ain’t Easy, now in ebook format, is about the life of Preston County native, Eloise Morgan Milne; The Savage Murder of Skylar Neese (a New York Times bestseller, with coauthor Geoff Fuller) and Pretty Little Killers (also with Fuller), released July 8, 2014, and featured in the August 18 issue of People Magazine.

You can find these books either online or in print at a bookstore near you, at BenBella Books, Nellie Bly Books, Amazon, on iTunes and Barnes and Noble.

For an in-depth look at the damaging effects of the silence that surrounds abuse, please watch my live TEDx talk, given April 13, 2013, at Connecticut College.

Have a great day and remember, it’s whatever you want to make it!

~Daleen

Editor’s Note: Daleen Berry is a New York Times best-selling author and a recipient of the Pearl Buck Award in Writing for Social Change. She has won several other awards, for investigative journalism and her weekly newspaper columns, and Sister of Silence placed first in the West Virginia Writers’ Competition. Ms. Berry speaks about overcoming abuse through awareness, empowerment and goal attainment at conferences around the country. To read an excerpt of her memoir, please go to the Sister of Silence site. Check out the five-star review from ForeWord Reviews. Or find out why Kirkus Reviews called Ms. Berry “an engaging writer, her style fluid and easy to read, with welcome touches of humor and sustained tension throughout.”

November 18, 2014

Skip Black Friday—But Do Support Small Business Saturday and Your Local Merchants

While writing two books in one year and starting on two other books—yes, the sequel to Sister of Silence and another true-crime book—I’m afraid I’ve neglected my blog. But with the holiday shopping season upon us, and Black Friday 10 days away, I’d like to suggest you shop small this year. In a big way, by supporting your local merchants on Small Business Saturday.

Unlike the average American woman, I hate shopping. I will never be a fashionista, so I rarely know what style looks good on me. In fact, I consider myself fashion-challenged. As if that wasn’t bad enough, I really dislike seeing my distorted reflection in a dressing room mirror. It’s rare that I even find something I like well enough to buy, which makes the entire shopping experience frustrating—not to mention a total waste of my time and energy. So don’t expect to pass me in the mall.

With Connie Merandi, at Coni and Franc on High Street

However, like many working women, I realize that image is important. Dress for success and all that, right? I know the right clothes can speak volumes about your image. And if you don the wrong outfit, you won’t project the image you need to. (Imagine Katie Couric going on set wearing a plunging neckline and a miniskirt. Or Jennifer Aniston suited up like Barbara Walters.) Add to that the fact that any woman who has to be seen in public but who carries more than five extra pounds, knows that the camera is going to play havoc with that image and her weight—especially if she can’t fit into anything in her closet.

That was my situation last winter, in late February. To say I was a tad nervous about appearing on the Dr. Phil Show to promote my book would be a huge understatement. But that all changed after I went to Coni and Franc to find an outfit for that unique media opportunity. Not only did I leave feeling a few inches taller, but I looked slimmer, too—and I knew it. More important, I felt elegant, and full of poise. During a time I was under so much stress that I was having chest pains, Connie Merandi and her staff pampered me and reassured me and gave me the confidence to pull off such an important feat.

This is how they did it: they took a personal interest in me, and in my wardrobe needs. Connie, who knows how to take a woman’s lumps and bumps and make them invisible with just the right jacket, slacks or—equally important—undergarment, knew what would look good on my particular body style. She also knew what I should avoid wearing. And what would help me represent West Virginia (whose residents don’t always appear in the media wearing the most fashionable clothing) in a way that reflected well on the state.

Now here’s the thing about small-town, upscale boutiques like Coni and Franc: we look at their window displays and often think they are way out of our price range. I know I did. For years, I never went inside. Too much money, I thought.

And then I went inside. Because by then I was so pressed for time, I could not afford to fight traffic and drive across town to the mall or other clothing stores. I also knew I would be hard-pressed to find slacks that weren’t too long, meaning I would have to alter them myself—or find someone else to. That wasn’t an option, either. At that point I had more money than I had time.