Ginger Dehlinger's Blog, page 7

May 23, 2018

Some Excellent Publishing News

My short story, "Clouds from Up and Down" was published this week by the Longridge Review. Inspired by lyrics from Joni Mitchell's song "Both Sides Now," the story contrasts innocent, white cloud youthful days with the dark, stormy days of a marriage gone bad.

The Longridge Review is an e-zine that began as the Essays on Childhood project. Below is their mission which includes the nature of the essays they publish.

"Our mission is to present the finest essays on the mysteries of childhood experience, the wonder of adult reflection, and how the two connect over a lifespan.We are committed to publishing narratives steeped in reverence for childhood perceptions, but we seek essays that stretch beyond the clichés of childhood as simple, angelic, or easy. We feature writing that layers the events of the writer’s early years with learning or wisdom accumulated in adult life."Here is a link to the Longridge Review and my essay.

https://longridgereview.com/

The Longridge Review is an e-zine that began as the Essays on Childhood project. Below is their mission which includes the nature of the essays they publish.

"Our mission is to present the finest essays on the mysteries of childhood experience, the wonder of adult reflection, and how the two connect over a lifespan.We are committed to publishing narratives steeped in reverence for childhood perceptions, but we seek essays that stretch beyond the clichés of childhood as simple, angelic, or easy. We feature writing that layers the events of the writer’s early years with learning or wisdom accumulated in adult life."Here is a link to the Longridge Review and my essay.

https://longridgereview.com/

Published on May 23, 2018 15:04

May 8, 2018

Hot Irons, Cold Nights

Ironing was the weekly chore assigned to Tuesday. This was a logical arrangement since items washed on Monday could be pressed and put away in drawers or closets the following day.

Most homes were equipped with two heavy flat irons. One would be in use, one heating on the stove to keep the ironing process from being interrupted. Some households owned irons in several sizes. While an item being pressed was repositioned, the iron rested on a trivet.

Some items were pre-moistened to make smoothing easier, but steam irons had to wait for electricity. Invented in 1882, the so-called “electric flatiron” used steam. Since it weighed fifteen pounds and took forever to get hot enough to make steam, many changes had to be made to its design before steam irons gained commercial success in the 1940’s and 50’s.

Ironing was done on any flat surface available, often the kitchen table, sometimes a mattress. The familiar curve-shaped ironing board was invented in 1892 by Sarah Boone, an African-American woman.

Part II of Never Done, titled “Hot Irons, Cold Nights,” includes scenes featuring both ironing and branding irons. Below are two excerpts that describe some of the ironing that took place in the home as described above.

Clara spit on the base of her iron to check the temperature. It had to be hot enough to remove wrinkles, yet not so hot it would scorch the only dress shirt Vincent owned. Satisfied with the sizzle, she spread a thin coat of beeswax on the iron’s base to keep it from sticking. A second iron heated on top of the wood stove, ready to trade places when the first one cooled.

Finished with the sweeping and dusting, Clara got to work cleaning the beeswax off her irons. While preparing for Vincent’s departure, she hadn’t had time to give them a thorough scrubbing. She sat at the table, and using a large square of sandpaper, spent the next hour scrubbing off the stubborn, baked-on wax.

Most homes were equipped with two heavy flat irons. One would be in use, one heating on the stove to keep the ironing process from being interrupted. Some households owned irons in several sizes. While an item being pressed was repositioned, the iron rested on a trivet.

Some items were pre-moistened to make smoothing easier, but steam irons had to wait for electricity. Invented in 1882, the so-called “electric flatiron” used steam. Since it weighed fifteen pounds and took forever to get hot enough to make steam, many changes had to be made to its design before steam irons gained commercial success in the 1940’s and 50’s.

Ironing was done on any flat surface available, often the kitchen table, sometimes a mattress. The familiar curve-shaped ironing board was invented in 1892 by Sarah Boone, an African-American woman.

Part II of Never Done, titled “Hot Irons, Cold Nights,” includes scenes featuring both ironing and branding irons. Below are two excerpts that describe some of the ironing that took place in the home as described above.

Clara spit on the base of her iron to check the temperature. It had to be hot enough to remove wrinkles, yet not so hot it would scorch the only dress shirt Vincent owned. Satisfied with the sizzle, she spread a thin coat of beeswax on the iron’s base to keep it from sticking. A second iron heated on top of the wood stove, ready to trade places when the first one cooled.

Finished with the sweeping and dusting, Clara got to work cleaning the beeswax off her irons. While preparing for Vincent’s departure, she hadn’t had time to give them a thorough scrubbing. She sat at the table, and using a large square of sandpaper, spent the next hour scrubbing off the stubborn, baked-on wax.

Published on May 08, 2018 13:03

April 12, 2018

Cowboys and Clotheslines

Before the invention of electricity led to such labor-saving devices as automatic clothes washers and driers, Monday was the day most American housewives did laundry. Since Monday followed a day of rest it was the best day of the week to accomplish this demanding chore.

Water had to be hauled, sometimes from great distances, and boiled on the stove. Clothes were scrubbed on washboards and excess water wrung out by hand or with hand-cranked wringers called mangles. Neither method was as effective at removing water as a modern washing machine's spin cycle.

After everything was washed it had to be rinsed, the dirtiest items boiled on the stove, and starch or bluing added before a week-s worth of laundry was ready to be dried. More heavy lifting followed as women loaded the family's clothes, sheets, towels, etc.( still laden with water) into baskets and carried them outside. Hanging wet laundry onto clotheslines meant bending, lifting, reaching, pinning, repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat until every item had been hung, dried, and carried back to the house.

Although Part I of my novel Never Done doesn't focus on this Monday chore, I included it in the first scene while I introduced the protagonist, Clara. Below is how "Cowboys and Clotheslines" begins.

A blue-gray dawn cooled the parched San Luis Valley that day as Clara grabbed a bucket for the first

of many trips she’d make for water. La Jara Creek was only a stone’s throw from the back of the house, but a bucket of water was a two-handed carry for a girl of fourteen.

It was the middle of July. She wore a cuffed and collared blouse, full petticoat, long linen skirt, and button-top boots. By noon she was wiping her brow with the sleeve of her blouse. Her shoulders ached and her neck had a crick in it from hanging clothes on a line she could barely reach. Taught not to complain, she dealt with the drudgery in silence, wishing she’d been allowed to go to Santa Fe with the others.

“How much is left?” she asked her Aunt Lou halfway through the afternoon.

“Just Albert’s work clothes. I put them to boiling on the stove.”

Clara sighed, knowing her next task would be scrubbing the stains out of her pa’s clothes. Ranch work turned even a persnickety cowboy into a dirt ball, and Albert, who worked right alongside his men, got just as dirty as they did.

“When do you think Pa and the others will be back?”

“Anytime now…hopefully before nightfall.”

Twenty-two and unmarried, Lou was the youngest of Albert’s sisters. Her slender frame was bent over the rinse tub as she wrung out the contents piece by piece. A few strands of her hair had come loose. She tucked the hair behind her ears, and then hefted a basket of wet sheets as if it held cottonwood fluff. “Hurry up,” she said as she walked toward the clotheslines with the basket. “We need to finish before they arrive.”

Water had to be hauled, sometimes from great distances, and boiled on the stove. Clothes were scrubbed on washboards and excess water wrung out by hand or with hand-cranked wringers called mangles. Neither method was as effective at removing water as a modern washing machine's spin cycle.

After everything was washed it had to be rinsed, the dirtiest items boiled on the stove, and starch or bluing added before a week-s worth of laundry was ready to be dried. More heavy lifting followed as women loaded the family's clothes, sheets, towels, etc.( still laden with water) into baskets and carried them outside. Hanging wet laundry onto clotheslines meant bending, lifting, reaching, pinning, repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat until every item had been hung, dried, and carried back to the house.

Although Part I of my novel Never Done doesn't focus on this Monday chore, I included it in the first scene while I introduced the protagonist, Clara. Below is how "Cowboys and Clotheslines" begins.

A blue-gray dawn cooled the parched San Luis Valley that day as Clara grabbed a bucket for the first

of many trips she’d make for water. La Jara Creek was only a stone’s throw from the back of the house, but a bucket of water was a two-handed carry for a girl of fourteen.

It was the middle of July. She wore a cuffed and collared blouse, full petticoat, long linen skirt, and button-top boots. By noon she was wiping her brow with the sleeve of her blouse. Her shoulders ached and her neck had a crick in it from hanging clothes on a line she could barely reach. Taught not to complain, she dealt with the drudgery in silence, wishing she’d been allowed to go to Santa Fe with the others.

“How much is left?” she asked her Aunt Lou halfway through the afternoon.

“Just Albert’s work clothes. I put them to boiling on the stove.”

Clara sighed, knowing her next task would be scrubbing the stains out of her pa’s clothes. Ranch work turned even a persnickety cowboy into a dirt ball, and Albert, who worked right alongside his men, got just as dirty as they did.

“When do you think Pa and the others will be back?”

“Anytime now…hopefully before nightfall.”

Twenty-two and unmarried, Lou was the youngest of Albert’s sisters. Her slender frame was bent over the rinse tub as she wrung out the contents piece by piece. A few strands of her hair had come loose. She tucked the hair behind her ears, and then hefted a basket of wet sheets as if it held cottonwood fluff. “Hurry up,” she said as she walked toward the clotheslines with the basket. “We need to finish before they arrive.”

Published on April 12, 2018 09:35

March 1, 2018

The Seven Parts of Never Done

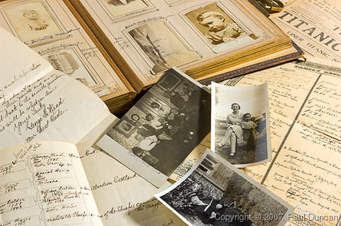

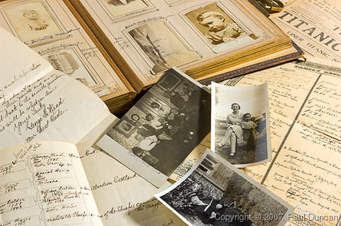

When I decided to write a novel based on my great-grandmother's life, I read and reread her hand-written memoir, looking for inspiration. What impressed me was how hard she worked most of her life. Work isn't a very compelling subject, so I decided to include it in my story, but not focus on it. For a more detailed description of woman's work, I recommend Never Done, A History of American Housework by Susan Strasser.

In an attempt to organize the 148 pages of my great-grandmother's manuscript, I began going through it paragraph by paragraph, highlighting every mention of work. Thankfully one of my cousins had transcribed our great-grandmother's handwritten life story into a Word document. In the margins of the Word document I wrote baking, cleaning, doing laundry, etc., so I could find what I was looking for when I wanted to mention that particular task in my story.

There are many versions of the children's nursery rhyme, “Here We Go ‘Round the Mulberry Bush." The one I recall describes the tasks women in the past performed on certain days of the week. "This is the way we wash our clothes," for example. Using the typical Monday--laundry, Tuesday--ironing, pattern, I decided to write Never Done in seven parts—each part representing one day of the week and its related chore.

So I created seven Word documents, naming them Monday thru Sunday. Then I went back through my margin notes and transferred the work incidents into the appropriate document of the week. Later, as my novel came together, I revised the names of the parts to reflect both the daily task and what takes place in the story during that part. The appropriate workday is mentioned somewhere during each part of my story, but only as background or as the setting for a scene.

That method of organizing my story was appropriate for Monday through Saturday, but in the past, Americans considered Sunday to be a day of rest. My great-grandmother never seemed to rest, so in part VII, I wrote about the devastating effects of Spanish flu on her life, as well as the people of Colorado, and named it "No Rest."

Part I: “Cowboys and Clotheslines”

Part II: “Hot Irons, Cold Nights” Part III: “Make Do and Mend” Part IV: “To Market, To Market” Part V: “New Brooms Sweep Clean” Part VI: “Live, Love, Bake” Part VII: “No Rest”

In an attempt to organize the 148 pages of my great-grandmother's manuscript, I began going through it paragraph by paragraph, highlighting every mention of work. Thankfully one of my cousins had transcribed our great-grandmother's handwritten life story into a Word document. In the margins of the Word document I wrote baking, cleaning, doing laundry, etc., so I could find what I was looking for when I wanted to mention that particular task in my story.

There are many versions of the children's nursery rhyme, “Here We Go ‘Round the Mulberry Bush." The one I recall describes the tasks women in the past performed on certain days of the week. "This is the way we wash our clothes," for example. Using the typical Monday--laundry, Tuesday--ironing, pattern, I decided to write Never Done in seven parts—each part representing one day of the week and its related chore.

So I created seven Word documents, naming them Monday thru Sunday. Then I went back through my margin notes and transferred the work incidents into the appropriate document of the week. Later, as my novel came together, I revised the names of the parts to reflect both the daily task and what takes place in the story during that part. The appropriate workday is mentioned somewhere during each part of my story, but only as background or as the setting for a scene.

That method of organizing my story was appropriate for Monday through Saturday, but in the past, Americans considered Sunday to be a day of rest. My great-grandmother never seemed to rest, so in part VII, I wrote about the devastating effects of Spanish flu on her life, as well as the people of Colorado, and named it "No Rest."

Part I: “Cowboys and Clotheslines”

Part II: “Hot Irons, Cold Nights” Part III: “Make Do and Mend” Part IV: “To Market, To Market” Part V: “New Brooms Sweep Clean” Part VI: “Live, Love, Bake” Part VII: “No Rest”

Published on March 01, 2018 12:52

February 1, 2018

100 Years Ago

The Global Pandemic of 1918Ginger Dehlinger

Bend, Oregon

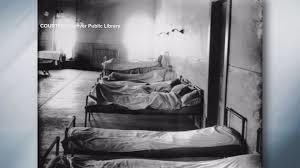

One hundred years have passed since that grim reaper variously called Spanish flu, Spanish Lady, French flu, or “La Grippe,” sickened one-third of the world’s inhabitants (roughly 500 million people). Death estimates vary, some being as high as 100 million people. Due to poor record-keeping in 1918/19, we don’t have an exact count. One fact, however, is certain—the Spanish flu caused more deaths than all military personnel killed by cannon, gunfire, bayonets, or poison gas during World War I.

My paternal grandfather was one of the fatalities. He was living in Naturita, Colorado when he, his pregnant wife, and three young children came down with the deadly flu. His family survived. Two months after my grandfather died, his wife gave birth to my father. As a child, that unfortunate sequence of events always held a morbid fascination for me. Decades later I wrote a fictionalized account of the flu’s impact on my family in Never Done, a novel.

While doing research for the book, I was shocked by what I learned, yet so riveted I had to force myself to stop reading about the disease and get back to writing about it. I was surprised to learn how easily the Spanish flu spread. Touching a flu patient, even being in the same room was enough to catch it, making the 1918 flu more virulent than Europe’s bubonic plague. Although the plague resulted in more deaths, they occurred over a span of two centuries versus one and a half years for Spanish flu.

The fourteenth century plague was spread by rodents and their lice, whereas the 1918 flu was a virus. Early in the twentieth century, few scientists, let alone doctors knew a virus pathogen even existed. An estimated 25 percent of the US population was infected with the baffling illness, and as many as 650,000 Americans died from it. The mountainous regions of Colorado were particularly hard hit due to the Western Slope’s large concentration of miners, men whose lungs were already compromised by the dust and bad air they breathed underground.

Crowded conditions in cities also increased the likelihood of catching the disease. At its height, the epidemic killed 759 Philadelphians in one day. President Wilson caught the flu while in Paris negotiating the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. It took him a long time to recover, leading me to wonder if the stroke he suffered four months after returning to the White House was related to the disease. Multiple theories exist as to where the twentieth century flu began—Spain, France, Austria, Vietnam. Current thinking is the virus originated in Haskell County, Kansas in January of 1918. Symptoms during that early outbreak were more like common flu, but the rate it spread caused a local doctor to report it to the U.S. Public Health Service. A few of the men exposed to the Haskell County flu carried it with them to a military training facility in central Kansas. From there the disease spread to other US bases, then to the civilian populations of nearby towns and cities, and eventually to Europe via troop ships. During the first seven or eight months of the epidemic, hundreds of thousands died in Europe and North America, but not nearly as many as would succumb later. The first wave was mild enough that French and British troops referred to it as “three-day fever.” However, US and European officials, worried flu headlines would disrupt the war effort, censored all news of the disease, resulting in rumor and panic. Speculation filled the phone lines, some people even claiming the epidemic was a secret weapon formulated by the Germans. Then the flu virus raised its ugly head in Spain. Thousands of Spaniards contracted the disease, but it wasn’t until King Alfonso XIII came down with it that Spanish newspapers started covering the flu in detail. Spain wasn’t a combatant in World War I, thus the Spanish press wasn’t censored. Their widespread reporting, the only news to be had about the flu, quickly gave the disease its Spanish label. By July of 1918 the epidemic appeared to be lessening. A month later, a more virulent strain of the virus appeared in Europe and Africa, returning in an explosion deadlier than the war itself. During the first wave most of the victims were the young, old, or infirm. In August, when the second wave began, the disease was more often fatal to healthy young adults. As the flu raced through the United States and Europe, daily routines were put on hold. Schools were closed, stores padlocked. People stayed home, fearful of talking to others, fearful of even breathing. Many who did venture out wore the poor quality surgical masks in use at the time. Made of porous fabric, the masks did little or nothing to protect the people who wore them. Flu symptoms began simply enough with a headache, runny nose, or sore throat. Following in quick succession were fever, nausea, aching joints, and cough. The person infected became so fatigued he or she could barely stand. Dark, reddish spots or an overall redness appeared on some faces, and within hours the virus attacked the patient’s lungs in a brutal pneumonia. In the worst cases, lungs filled with a bloody froth and the patient bled from their nose, ears, or eyes.Some died less than a day after the first symptoms appeared. Other victims, like several in my family, suffered for weeks. So did noted author, Katherine Anne Porter. Miss Porter contracted the flu while living in Denver. After a prolonged ordeal, delirious much of the time, she recovered. She later fictionalized her near-death experience in the classic story, “Pale Horse, Pale Rider.” Several theories exist as to why the second wave of the flu killed so many adults in their prime. Thousands of victims were young soldiers, leading to the belief damp trenches, infected wounds, or overcrowded quarters were to blame. According to historian John M. Barry, a leading expert on the pandemic, the targeting of healthy adults may have been caused by an overreaction of their immune systems. In his book, The Great Influenza, Barry tells of a group of scientists who salvaged the 1918 virus from long-frozen bodies, and then injected it into lab animals. The animals experienced rapid respiratory failure and death when their immune systems tackled the disease with far greater intensity than they would an ordinary virus. Based on their findings, the researchers postulated that the strong immune systems of healthy adults attacked the virus, and then, in hyper attack mode, turned against the body of the host. Weaker immune systems fought the virus and eased off when it was under control. Worldwide, the death toll peaked during the fourth quarter of 1918. October, the same month my grandfather died, was particularly deadly in the United States. Philadelphia reported over 4,500 deaths during one week in October. Less than a month later, the number of fatalities had dropped dramatically. In 1919, sporadic flu-related obituaries continued to appear in American newspapers, but by summer the disease had run its course. Widespread speculation exists as to why the number of casualties suddenly dropped. Was it just a coincidence the epidemic ended about the same time as the war? Perhaps doctors learned better treatments. Maybe the virus mutated to a less lethal strain. Medical knowledge has expanded vastly since 1918, but we may never know why that particular strain of flu came and went so quickly. During the last 100 years, the medical community has fought polio, swine flu, bird flu, AIDS, Ebola and other highly infectious diseases. Panic erupts whenever the public hears a new virus is wreaking havoc somewhere. Then doctors find a treatment, and front-page headlines disappear. In 1918, especially during the month of October when flu deaths mounted and doctors hadn’t found a cure, many people believed it signaled the end of mankind. Since then, the world’s population has mushroomed; likewise the number of people traveling across borders. Medicine has also advanced, but if new viruses evolve, and they will, the chance of another global pandemic is even greater now than it was in the last century.

ReferencesBarry, John M. “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America.” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2017.Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin, 2004.

Dehlinger, Ginger. Never Done. The Wild Rose Press, April 21, 2017.

Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Dead Zone.” The New Yorker. September 29, 1997.

Caitlin Switzer. “When the Flu Came to Colorado…and the World.” The Montrose Mirror Online, April 17, 2013.

Knox, Richard. “Killer Flu Reconstructed,” PBS radio, All Things Considered, October 5, 2005.

Porter, Katherine. The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter. Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt Publishing Company. 1965.

“1918 Flu Pandemic-Facts & Summary,” HISTORY.com, n.d., Web. December 18, 2017.

Bend, Oregon

One hundred years have passed since that grim reaper variously called Spanish flu, Spanish Lady, French flu, or “La Grippe,” sickened one-third of the world’s inhabitants (roughly 500 million people). Death estimates vary, some being as high as 100 million people. Due to poor record-keeping in 1918/19, we don’t have an exact count. One fact, however, is certain—the Spanish flu caused more deaths than all military personnel killed by cannon, gunfire, bayonets, or poison gas during World War I.

My paternal grandfather was one of the fatalities. He was living in Naturita, Colorado when he, his pregnant wife, and three young children came down with the deadly flu. His family survived. Two months after my grandfather died, his wife gave birth to my father. As a child, that unfortunate sequence of events always held a morbid fascination for me. Decades later I wrote a fictionalized account of the flu’s impact on my family in Never Done, a novel.

While doing research for the book, I was shocked by what I learned, yet so riveted I had to force myself to stop reading about the disease and get back to writing about it. I was surprised to learn how easily the Spanish flu spread. Touching a flu patient, even being in the same room was enough to catch it, making the 1918 flu more virulent than Europe’s bubonic plague. Although the plague resulted in more deaths, they occurred over a span of two centuries versus one and a half years for Spanish flu.

The fourteenth century plague was spread by rodents and their lice, whereas the 1918 flu was a virus. Early in the twentieth century, few scientists, let alone doctors knew a virus pathogen even existed. An estimated 25 percent of the US population was infected with the baffling illness, and as many as 650,000 Americans died from it. The mountainous regions of Colorado were particularly hard hit due to the Western Slope’s large concentration of miners, men whose lungs were already compromised by the dust and bad air they breathed underground.

Crowded conditions in cities also increased the likelihood of catching the disease. At its height, the epidemic killed 759 Philadelphians in one day. President Wilson caught the flu while in Paris negotiating the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. It took him a long time to recover, leading me to wonder if the stroke he suffered four months after returning to the White House was related to the disease. Multiple theories exist as to where the twentieth century flu began—Spain, France, Austria, Vietnam. Current thinking is the virus originated in Haskell County, Kansas in January of 1918. Symptoms during that early outbreak were more like common flu, but the rate it spread caused a local doctor to report it to the U.S. Public Health Service. A few of the men exposed to the Haskell County flu carried it with them to a military training facility in central Kansas. From there the disease spread to other US bases, then to the civilian populations of nearby towns and cities, and eventually to Europe via troop ships. During the first seven or eight months of the epidemic, hundreds of thousands died in Europe and North America, but not nearly as many as would succumb later. The first wave was mild enough that French and British troops referred to it as “three-day fever.” However, US and European officials, worried flu headlines would disrupt the war effort, censored all news of the disease, resulting in rumor and panic. Speculation filled the phone lines, some people even claiming the epidemic was a secret weapon formulated by the Germans. Then the flu virus raised its ugly head in Spain. Thousands of Spaniards contracted the disease, but it wasn’t until King Alfonso XIII came down with it that Spanish newspapers started covering the flu in detail. Spain wasn’t a combatant in World War I, thus the Spanish press wasn’t censored. Their widespread reporting, the only news to be had about the flu, quickly gave the disease its Spanish label. By July of 1918 the epidemic appeared to be lessening. A month later, a more virulent strain of the virus appeared in Europe and Africa, returning in an explosion deadlier than the war itself. During the first wave most of the victims were the young, old, or infirm. In August, when the second wave began, the disease was more often fatal to healthy young adults. As the flu raced through the United States and Europe, daily routines were put on hold. Schools were closed, stores padlocked. People stayed home, fearful of talking to others, fearful of even breathing. Many who did venture out wore the poor quality surgical masks in use at the time. Made of porous fabric, the masks did little or nothing to protect the people who wore them. Flu symptoms began simply enough with a headache, runny nose, or sore throat. Following in quick succession were fever, nausea, aching joints, and cough. The person infected became so fatigued he or she could barely stand. Dark, reddish spots or an overall redness appeared on some faces, and within hours the virus attacked the patient’s lungs in a brutal pneumonia. In the worst cases, lungs filled with a bloody froth and the patient bled from their nose, ears, or eyes.Some died less than a day after the first symptoms appeared. Other victims, like several in my family, suffered for weeks. So did noted author, Katherine Anne Porter. Miss Porter contracted the flu while living in Denver. After a prolonged ordeal, delirious much of the time, she recovered. She later fictionalized her near-death experience in the classic story, “Pale Horse, Pale Rider.” Several theories exist as to why the second wave of the flu killed so many adults in their prime. Thousands of victims were young soldiers, leading to the belief damp trenches, infected wounds, or overcrowded quarters were to blame. According to historian John M. Barry, a leading expert on the pandemic, the targeting of healthy adults may have been caused by an overreaction of their immune systems. In his book, The Great Influenza, Barry tells of a group of scientists who salvaged the 1918 virus from long-frozen bodies, and then injected it into lab animals. The animals experienced rapid respiratory failure and death when their immune systems tackled the disease with far greater intensity than they would an ordinary virus. Based on their findings, the researchers postulated that the strong immune systems of healthy adults attacked the virus, and then, in hyper attack mode, turned against the body of the host. Weaker immune systems fought the virus and eased off when it was under control. Worldwide, the death toll peaked during the fourth quarter of 1918. October, the same month my grandfather died, was particularly deadly in the United States. Philadelphia reported over 4,500 deaths during one week in October. Less than a month later, the number of fatalities had dropped dramatically. In 1919, sporadic flu-related obituaries continued to appear in American newspapers, but by summer the disease had run its course. Widespread speculation exists as to why the number of casualties suddenly dropped. Was it just a coincidence the epidemic ended about the same time as the war? Perhaps doctors learned better treatments. Maybe the virus mutated to a less lethal strain. Medical knowledge has expanded vastly since 1918, but we may never know why that particular strain of flu came and went so quickly. During the last 100 years, the medical community has fought polio, swine flu, bird flu, AIDS, Ebola and other highly infectious diseases. Panic erupts whenever the public hears a new virus is wreaking havoc somewhere. Then doctors find a treatment, and front-page headlines disappear. In 1918, especially during the month of October when flu deaths mounted and doctors hadn’t found a cure, many people believed it signaled the end of mankind. Since then, the world’s population has mushroomed; likewise the number of people traveling across borders. Medicine has also advanced, but if new viruses evolve, and they will, the chance of another global pandemic is even greater now than it was in the last century.

ReferencesBarry, John M. “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America.” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2017.Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin, 2004.

Dehlinger, Ginger. Never Done. The Wild Rose Press, April 21, 2017.

Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Dead Zone.” The New Yorker. September 29, 1997.

Caitlin Switzer. “When the Flu Came to Colorado…and the World.” The Montrose Mirror Online, April 17, 2013.

Knox, Richard. “Killer Flu Reconstructed,” PBS radio, All Things Considered, October 5, 2005.

Porter, Katherine. The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter. Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt Publishing Company. 1965.

“1918 Flu Pandemic-Facts & Summary,” HISTORY.com, n.d., Web. December 18, 2017.

Published on February 01, 2018 09:02

January 7, 2018

Where I Write

Here is where I spend a few hours of most of my days. I take up roughly one quarter of the small third bedroom my husband and I refer to as the den. In addition to my writing corner, the den contains bookcases, a sofa, and a great chair to sit in and read. My writing space is always messy, but I know where to dig for what I need.

In the reading chair, usually asleep, is Kiki, my writing buddy. I think the sound of my typing soothes her. On the other hand, she sleeps most of the time.

On the wall in front of me is a clock my cousin Arlin Phillipps (Arlie) made from a large burl. He removed the burl from a tree, sliced it, and coated it with fiberglass resin. After the resin dried, he added numerals, hands, and a pendulum. Pictures don't do it justice.

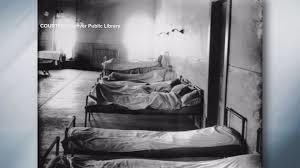

To the left of my work space hangs a framed book carving of my novel Brute Heart. When I saw the artist's work at an art fair, I just had to have her create this beautiful three-dimensional heirloom. The artist, Sarah Bean, lives in Gold Beach, Oregon. Many of her book carvings hang in the Library of Congress.

The process is rather difficult to explain. First Sarah separates a soft cover book into two halves. Then she uses some kind of very sharp cutting tool to carve intricate designs into the pages, going deeper with some cuts than others. Finally she adds the cover, pictures, and miscellaneous small items to create a collage representing the physical book as well as the story within. Someday I am going to have Sarah make one for my second novel, Never Done.

Published on January 07, 2018 12:07

December 7, 2017

Bad Grammar

Bad grammar makes me shudder. A person doesn't have to know the rules, but can't they hear how terrible it sounds?

Published on December 07, 2017 15:56

November 7, 2017

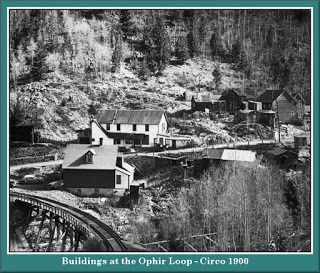

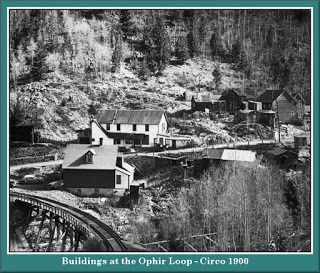

Pinterest is a photo-sharing website that is great fun to browse. Type almost anything in the "search" window and you will find pictures of it. I enjoyed the experience so much I created boards representing my two novels--Brute Heart and Never Done.

In my writing I try to describe people, places, and things well enough for readers to visualize them, but now they can go to my Pinterest boards and see actual pictures of some of them. Not the characters, though. They need to be assembled in each reader's imagination.

Below are a few pictures from my Pinterest boards. To see more go to https://www.pinterest.com/gdehlinger/

In my writing I try to describe people, places, and things well enough for readers to visualize them, but now they can go to my Pinterest boards and see actual pictures of some of them. Not the characters, though. They need to be assembled in each reader's imagination.

Below are a few pictures from my Pinterest boards. To see more go to https://www.pinterest.com/gdehlinger/

Published on November 07, 2017 10:45

October 6, 2017

Five-Star Reviews

Reviews for Never Done have been good so far. Below are a few of them.

This historical book about a very strong woman in Colorado was one of the most moving books I have read. I was impressed with G. Dehlinger's research on cattle drives, the trees and flora of Colorado as well as the dress of the times and how they dealt with the lack of amenities. The relationships this woman, Clara, had with family members and others is quite intriguing and kept me engrossed throughout. L.S. Raleigh, NC

Dehlinger has done it again with another well-written and thoroughly researched novel. The characters are flawed, and the relationships are not perfect. Geneva and Clara never reach the easy friendship you're rooting for, yet there'a feeling of peace in the end. When Clara triumphs over a hardship, you root for her. My emotions ran the gamut as I read this book, and I look forward to sharing it with others. Loved the descriptions Dehlinger uses for the towns, mountains, dangerous roads, and animals. It was an enjoyable novel, and I hope she writes another one! S.R. Bend, OR

I love stories that are based on historic truth and Ms. Dehlinger had a clear window to history, when she acknowledged the extraordinary life of her great grandmother who lived to age 98, leaving behind a hand-written memoir. The result is a well-written fact-based fictional view of one family’s survival in Colorado in the latter part of the 19th century. Survival was always tenuous in changing times, and particularly hard on women with agendas that were “Never Done.” Heroines Clara and Geneva are teenage cousins whose friendship is shattered when one becomes stepmother to the other. Both grow up fast in times that most of us can hardly imagine. Ms. Dehlinger paints a realistic picture—with prose to match—about their troubled relationship and double coin of survival over thirty plus years. I was brought to tears when the drama climaxes in the 1918 flu pandemic that killed more people than WWI. “Never Done” is a vivid testimonial to the indomitable spirit of all ancestors who struggled to survive while holding family together. I look forward to reading more from this talented author who seamlessly blends fact with fiction in a well-told relatable and thoroughly entertaining story. C. F. Minneapolis, MN

Ginger Dehlinger has written a novel based on her great grandmother's life in the early west. The girls are very young to have faced the hardships of living in primitive surroundings with which most adults would not be able to cope today.The author's research into the details of life in the period make her writing authentic and the story rings true. Well done! K.B. Bethesda, MD

This historical book about a very strong woman in Colorado was one of the most moving books I have read. I was impressed with G. Dehlinger's research on cattle drives, the trees and flora of Colorado as well as the dress of the times and how they dealt with the lack of amenities. The relationships this woman, Clara, had with family members and others is quite intriguing and kept me engrossed throughout. L.S. Raleigh, NC

Dehlinger has done it again with another well-written and thoroughly researched novel. The characters are flawed, and the relationships are not perfect. Geneva and Clara never reach the easy friendship you're rooting for, yet there'a feeling of peace in the end. When Clara triumphs over a hardship, you root for her. My emotions ran the gamut as I read this book, and I look forward to sharing it with others. Loved the descriptions Dehlinger uses for the towns, mountains, dangerous roads, and animals. It was an enjoyable novel, and I hope she writes another one! S.R. Bend, OR

I love stories that are based on historic truth and Ms. Dehlinger had a clear window to history, when she acknowledged the extraordinary life of her great grandmother who lived to age 98, leaving behind a hand-written memoir. The result is a well-written fact-based fictional view of one family’s survival in Colorado in the latter part of the 19th century. Survival was always tenuous in changing times, and particularly hard on women with agendas that were “Never Done.” Heroines Clara and Geneva are teenage cousins whose friendship is shattered when one becomes stepmother to the other. Both grow up fast in times that most of us can hardly imagine. Ms. Dehlinger paints a realistic picture—with prose to match—about their troubled relationship and double coin of survival over thirty plus years. I was brought to tears when the drama climaxes in the 1918 flu pandemic that killed more people than WWI. “Never Done” is a vivid testimonial to the indomitable spirit of all ancestors who struggled to survive while holding family together. I look forward to reading more from this talented author who seamlessly blends fact with fiction in a well-told relatable and thoroughly entertaining story. C. F. Minneapolis, MN

Ginger Dehlinger has written a novel based on her great grandmother's life in the early west. The girls are very young to have faced the hardships of living in primitive surroundings with which most adults would not be able to cope today.The author's research into the details of life in the period make her writing authentic and the story rings true. Well done! K.B. Bethesda, MD

Published on October 06, 2017 09:43

September 8, 2017

Opportunity to Promote My Writing

I'm excited to be the guest speaker at this month's Bend Genealogical Society meeting. I was invited after one of their members, a friend of mine, read Never Done. Since Never Done is based on information gleaned from my great-grandmother's memoir, she thought her club members would find it interesting to learn how the story came about. I took her idea and expanded it, creating a PowerPoint presentation that covers not only my great-grandmother's memoir, but many types of documents with story potential.

Title: "Family-Inspired Fiction: How to Use Family History & Documents to Create Stories"

Date: Tuesday, September 19, 2017

Time: 10:00 a.m.

Place: Williamson Hall (Williamson Hall is part of the Rock Arbor Villa Mobile Home Park at 2220 N.E. Hwy 20, Bend OR

Title: "Family-Inspired Fiction: How to Use Family History & Documents to Create Stories"

Date: Tuesday, September 19, 2017

Time: 10:00 a.m.

Place: Williamson Hall (Williamson Hall is part of the Rock Arbor Villa Mobile Home Park at 2220 N.E. Hwy 20, Bend OR

Published on September 08, 2017 10:39