Terri Windling's Blog, page 242

August 4, 2011

The Great Bunny Chase

Big drama while walking in a field close to our house this morning: Tilly caught a young rabbit, much to her own surprise -- for while she loves to give chase, this is the first time she's ever caught anything (except for bugs). I was alerted by the bunny's loud squeals, and called the pup off before any real harm was done. The poor little critter had had a bad scare, but it scampered away vigorously and it seemed all right. Tilly, meanwhile, was marched home in disgrace, ears flattened on her head (her "I'm sorry, really I am!" look), tail firmly between her legs...though really the fault was mine for taking her to that particular field at that early hour. It wasn't our usual crack-of-dawn walk; usually we're in the woods or up on the hill, not down in the farmer's field below, and I should have realized that the local rabbits have claimed that spot at the break of day.

Now, Tilly was born on a working farm and comes from long lines of hunting dogs, so the impulse to chase is bred in her bones. Living here in farm country, she's learned that she mustn't chase sheep, or cows, or bullocks on the Commons, or the wild ponies that come down from the moor. "And not bunnies either," I told her this morning. "Not when you're living with a bunny-girl painter like me." Yet I know all these human rules are confusing for a pup, so I made her a helpful chart:

On "daring to be foolish," once again

Here's a passage I love: it's Allen Ginsberg talking about the writing of poetry (although it applies to any creative endeavor), expressing some of the same things that I was trying to get at in my earlier post, Dare to be Foolish:

"The parts [of the work] that embarrass you the most," says Ginberg, "are usually the most interesting poetically, are usually the most naked of all, the rawest, the goofiest, the strangest and most eccentric and, at the same time, most representative, most universal...That was something I learned from Kerouac, which was that spontaneous writing can be embarrassing....The cure for that is to write things down which you will not publish and you won't show people. To write secretly...so you can actually be free to say anything you want.

"It means abandoning being a poet, abandoning your careerism, abandoning even the idea of writing any poetry, really abandoning, giving up as hopeless--abandoning the possibility of really expressing yourself to the nations of the world. Abandoning the idea of being a prophet with honor and dignity, and abandoning the glory of poetry and just settling down in the much of your own mind....You really have to make a resolution just to write for yourself...in the sense of not writing to impress yourself, but just writing what your self is saying."

Now this is, in a sense, the opposite advice from the Henry James quote I posted earlier this week, which seems to suggest that artists consider whether the work they're doing is worth doing before they embark upon it. Ginsberg, by contrast, advises working from the gut, the core, the raw and messy interior, without worrying too much about whether the world will value (or even needs to see) what it is we create. I tend to think that both pieces of advice are valid, and necessary to the creative process. The key, I suppose, is knowing which one to apply at what time, and for which project, and for which stage of a particular project.

When I'm writing, for example, I find that first drafts are my time for Ginsbergian flow, letting things emerge from the depth without censor (a freedom I achieve only by adhering to a strict rule of keeping my early drafts private). It's only in later drafts -- when I'm approaching my work more as an editor than an author -- that I can evaluate the text in the Jamesian way. And I've learned, over the years, not to let the Jamesian editor/critic into process too early, for then I am liable to be so self-conscious that I end up writing painfully s-l-o-w-ly...or writing nothing at all. I long ago discovered that I need to allow that first draft to be just as red, wrinkled, and bawling as a new born babe--a creature of beauty only to me, its mother--for that seems to be how my stories are born. The first draft is always and only for myself. It's the last draft that's for the readers.

August 2, 2011

Among the flowers

As Tilly perches among the flowers on a lazy summer afternoon, I'm reminded of what this spot looked like when we first moved into Bumblehill: a sad patch of land at the back of the yard by the border of the woods. First we built the two-room cabin that is used as Howard's office now....

...and then Howard put on his gardening cap and got to work on the land itself...

...transforming a muddy, weedy, unloved bit of ground ...

...into a garden rich in color and scent...

...full of birds and bees and butterflies...

...and one little black dog...

...who believes, of course, that he did it all just for her.

Fairy Tale Depravity

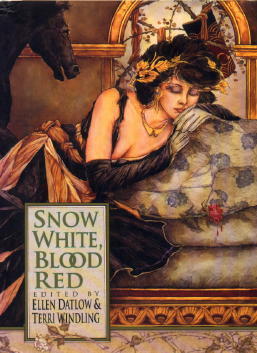

Ellen Datlow just alerted me to an interesting article published in The Guardian on June 29. It seems that a story from our Snow White, Blood Red anthology (a collection of re-told fairy tales for adult readers) has been denounced in the state-owned al-Akhbar newspaper in Egypt. Gracious! That's a first for us.

Ellen Datlow just alerted me to an interesting article published in The Guardian on June 29. It seems that a story from our Snow White, Blood Red anthology (a collection of re-told fairy tales for adult readers) has been denounced in the state-owned al-Akhbar newspaper in Egypt. Gracious! That's a first for us.

The offending story is Tanith Lee's "Snow-drop," an Angela-Carter-esque retelling of Snow White.

"It was on the reading list of a fantasy fiction course offered to final-year students during the first term of this academic year, 2010-2011," says The Guardian. "The short story, according to the al-Akhbar journalist, teaches nothing but depravity and moral degradation. It encourages perversion and is therefore 'a crime in the full sense of the word'. Brandishing his moral sword, he threatened to file a complaint of moral corruption to the public prosecutor and to sue all those involved in allowing this short story to corrupt innocent minds."

The power of fairy tales indeed.

Growing into your work...

From Art & Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland:

From Art & Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland:

"Writer Henry James once proposed three questions you could productively put to an artist's work: What was the artist trying to achieve? Did he/she succeed? The third's a zinger: Was it worth doing?

"The first two questions alone are worth the price of admission. They address art at a level that can be tested directly against real-world values and experience; they commit you to accepting the perspective of the maker into your own understanding of the work. In short, they ask you to respond to the work itself, without first pushing it through some aesthetic filter....

"But it's that third question -- Was it worth doing? -- that truly opens the universe. "

The art in this post is by Jacqueline Morreau and Jeanie Tomanek, two women I find enormously inspiring, whose creative work has these things in common:

1. It is beautiful, mythic, emotionally resonant, and intellectual compelling.

1. It is beautiful, mythic, emotionally resonant, and intellectual compelling.

2. It is created by artists doing their most powerful work in their maturity (they were born in 1929 and 1949 respectively), despite a youth-obsesssed media/arts culture still uncomfortable with older women.

1.) It answers Henry James' all-important third question with a rousing "Yes!"

Above and to the left,"Two Women" and "The Divided Self" by painter/printmaker Jacqueline Morreau, an American born artist now living in London. You'll find her website here, and an article about her in the JoMA archives here.

Above (to the right) and below: "Demeter's Search," "After with Beagle," and "Planting Moon" by painter/poet Jeanie Tomanek, who lives and works in Georgia. You'll find her website here, and an article about her in the JoMA archives here.

"Since my sixth year I have felt the impulse to represent the form of things; by the age of fifty I had published numberless drawings; but I am displeased with all I have produced before the age of seventy. It is at seventy-three that I have begun to understand the form and the true nature of birds, of fishes, of plants and so forth. Consequently, by the time I get to eighty, I shall have made much progress; at ninety, I shall get to the essense of things; at a hundred, I shall certainly come to a superior, undefinable position; and at the age of a hundred and ten, every point, every line, shall be alive. And I leave it to those who shall live as I have myself, to see if I have not kept my word."

-- Hokusai (1760-1849)

July 31, 2011

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It's a bit of dog-themed post today. Above: the American jazz singer Nellie McKay plays "The Dog Song" in Monterey, California, in 2008.

Below: the English singer/songwriter Cat Stevens (aka Yusuf Islam) performs "I Love My Dog" on the BBC in the 1970s. Despite the controversial religious views he adopted later in life, I still adore this man's early music -- which got me through some very hard years in my adolescence, bless him.

Want more? Try, Nina Nastasia's "A Dog's Life":

Pulp's "Dogs are Everywhere:

And The Be Good Tanya's "Dogsong":

And just so the cat-lovers don't feel left out,

here's The Stray Cats with "The Stray Cat Strut":

Today's tunes go out to my fellow-Faery Godmother Carol Amos (happy birthday tomorrow, Carol!), who is just as sappy about dogs as me and Howard. The pointer pup in the photo below is Juno, Carol's family dog (and Tilly's BFF).

"In the Doghouse," photograph by Carol Amos.

"In the Doghouse," photograph by Carol Amos.

July 29, 2011

Friday recommendations:

Sally Prue discusses searching for fairyland in the "Fairytale Reflection" series over at Katherine Langrish's Seven Miles of Steel Thistles.

Andy Letcher discusses the magic of weather on his music & writing blog.

Els Kushner discusses one of my favorite Elizabeth Goudge novels, Linnets and Valerians, at Tor.com.

Charles Tan discusses Karen Lord's fine novel, Redemption in Indigo, at Bibliophile Stalker.

Michael Sims discusses E.B. White (author of Charlotte's Web, etc.) and his relationship with animals in The Chronicle Review.

Carlin Roman discusses metaphors, also in The Chronicle Review.

John Barth discusses originality in The Atlantic. (Another article that comes at the subject of originality from a slightly different direction is Jonathan Lethem's absolutely brilliant "The Ecstasy of Influence," published in Harper's in 2007.)

Al Kennedy discusses writing and procrastination in The Guardian.

Kristin Naca discusses duende and eating poetry in a lyrical short piece in Poetry Magazine.

And here's an odd but interesting one (particularly if any of you are contemplating writing a 19th century murder-mystery): Deborah Blum discusses deadly foods in Lapham's Quarterly.

This week's fiction recommendations:

* "The Girl Who Ruled Fairyland -- For a Little While" by Catherynne M. Valente at Tor.com.

*"Swans" by Kelly Link, first published in the fairy tale anthology A Wolf at the Door (edited by Ellen Datlow and me), and now available on-line on the Fantasy Magazine site. There's also an interview with Kelly here.

This week's art recommendations:

* Heidi Kellenberger's delicious new blog, Uncovered Cover Art: A Sketchbook of Reimagined Children's Books.

* The Realm of Froud: the magical new online home of mythic artists Brian, Wendy, and Toby Froud.

* The new Phantasten Museum in Vienna, dedicated to fantastic, visionary, and surrealistic art.

* Also, check out the charming "Fox and Hermit" sketches recently posted by Larry MacDougall; and the magical beasties of "Mr. Finch" (the latter via Ruthie Reddon).

This week's videos:

* The first recommendation (from writer/editor Amal El-Mohtar) is "Blood Tea and Red String," the weirdly magical trailer for a stop-m0tion animated fairy tale film by Christiane Cegavske. To learn more about Cegavske's work, go here.

*In a completely different vein, the second recommendation (from photographer Stu Jenks) is "Rapture," a time-lapse photographic portrait of the American south-west by Tom Lowe. To learn more about Lowe's work, go here.

And lastly, Rex and Howard say "au revoir" at John Barleycorn. (Look closely at that top photo, or click on it to make it bigger, and you'll see our little Tilly poking her nose through the rails.)

July 27, 2011

The narrative of marriage

"The Meeting of Oberon and Titania" by Arthur Rackham

"The Meeting of Oberon and Titania" by Arthur Rackham

I've been re-reading one of my favorite books: Writing a Woman's Life by the late feminist scholar Carolyn G. Heilbrun (1926-2003). Ostensibly a survey of the way the lives of famous women have been portrayed by biographers, this slim volume also casts a sharp eye on the way women's stories are told today...and the manner in which such narratives influence the ways that we tell our own stories.

I first encountered the book twenty years ago, and have re-read it several times since, finding new things to ponder within it at each different stage of my own life's journey. This time, I've been struck anew by the chapter on marriage -- for I'm reading it now as a married woman myself (after spending much of my adult life in a more independent state), and thus have fresh interest in Heilbrun's reflections on marriage and its portrayal in women's stories. She writes:

"It is noteworthy that few works of fiction make marriage their central concern. As Northrup Frye puts it, with his accustomed clarity: 'The heroine who becomes a bride, and eventually, one assumes, a mother, on the last page of a romance, has accommodated herself to the cyclical movement: by her marriage...she completes the cycle and passes out of the story. We are usually given to understand that a happy and well-adjusted sexual life does not concern us as readers.' Fiction has largely rejected marriage as a subject, except in those instances where it is presented as a history of betrayal -- at worst an Updike hell, at best when Auden speaks of it as a game calling for 'patience, foresight, maneuver, like war, like marriage.' Marriage is very different than fiction presents it as being. We rarely examine its unromantic aspects."

"It is noteworthy that few works of fiction make marriage their central concern. As Northrup Frye puts it, with his accustomed clarity: 'The heroine who becomes a bride, and eventually, one assumes, a mother, on the last page of a romance, has accommodated herself to the cyclical movement: by her marriage...she completes the cycle and passes out of the story. We are usually given to understand that a happy and well-adjusted sexual life does not concern us as readers.' Fiction has largely rejected marriage as a subject, except in those instances where it is presented as a history of betrayal -- at worst an Updike hell, at best when Auden speaks of it as a game calling for 'patience, foresight, maneuver, like war, like marriage.' Marriage is very different than fiction presents it as being. We rarely examine its unromantic aspects."

One of the problems of the "romantic plot" (as it's constantly portrayed in our popular culture: in countless contemporary novels, films, t.v. shows, pop songs, etc., etc.) is that it's a narrative that focuses exclusively and relentlessly on the beginning of a relationship -- and then ends at the point of declaration, or conquest, or the exchange of marriage vows. Thus we're encouraged to think of the heady excitement inherent in a brand new attraction as the whole point of love -- with no interest left over for the intricate dance of a marriage or long-term partnership: the quieter romance of entwined lives spun out over years, over decades, over a lifetime. We are constantly bombarded with stories (films, songs, etc.) that lay down all-too-familiar scripts for how to behave as lovers in the throes of new passion -- but where are the stories (or films, or love songs) that tell us anything useful about the mysteries of marriage, the challenging work of true partnership?

And does this matter? Well, I think it does. Not everyone is blessed with the model of a functional marriage in their family background, and thus it's to stories we often turn for a glimpse of how else to construct our lives . . . and what we get from most books and films on the subject of marriage is a resounding silence. We're shown over, and over, and over again that it's courtship that counts, and the social pageant of the Wedding Day -- while marriage is a vague, misty, unexplored state, unworthy of drama or art. Marriage is the end of the tale.

Another quote from Heilbrun's excellent book:

"Most of us begin, aided by almost every aspect of our culture, hoping for a perfect marriage. What this means is that we accept sexual attractiveness as a clue to finding our way in the labyrinth of marriage. It almost never is. Oddly enough, the media, which promise marriage as the happy ending, almost simultaneously show it, after several years, to be more ending than happy. But the dream lives on that this time will be different.

"Most of us begin, aided by almost every aspect of our culture, hoping for a perfect marriage. What this means is that we accept sexual attractiveness as a clue to finding our way in the labyrinth of marriage. It almost never is. Oddly enough, the media, which promise marriage as the happy ending, almost simultaneously show it, after several years, to be more ending than happy. But the dream lives on that this time will be different.

"Perhaps the reason the truth is so little told is that it sounds quotidian, bourgeois, even like advocating proportion, that most unappealing of all virtues. But E. M. Forester understood this: when someone suggested that truth is halfway between extremes, his answer (in Howards End) was, "No; truth, being alive, was not halfway between anything. It was only to be found by continuous excursions into either realm, and though proportion is the final secret, to espouse it at the outset is to ensure sterility." Proportion is the final secret, and that is why all good marriages are what Stanley Cavell calls 'remarriages,' and not lust masquerading as passion."

A little later on, Heilbrun explains what she means by the term "remarriage":

"I have spoken of reinventing marriage, of marriages achieving their rebirth in the middle age of the partners. This phenomenon has been called the 'comedy of remarriage' by Stanley Cavell, whose Pursuits of Happiness, a film book, is perhaps the best marriage manual ever published. One must, however, translate his formulation from the language of Hollywood, in which he developed it, into the language of middle age: less glamour, less supple youth, less fantasyland. Cavell writes specifically of Hollywood movies of the 1930s and 1940s in which couples -- one partner is often the dazzling Cary Grant -- learn to value each other, to educate themselves in equality, to remarry. Cavell recognizes that the actresses in these movie -- often the dazzling Katherine Hepburn -- are what made them possible. If read not as an account of beautiful people in hilarious situations, but as a deeply philosophical discussion of marriage, his book contains what are almost aphorisms of marital achievement. For example: ....'[The romance of remarriage] poses a structure in which we are permanently in doubt who the hero is, that is, whether it is the male or female who is the active partner, which of them is in quest, who is following whom.'

"Above all, despite the sexual attractiveness of the actors in the movies he discusses, Cavell knows that sexuality is not the ultimate secret in these marriage: 'in God's intention a meet and happy conversation is the chiefest and noblest end of marriage. Here is the reason that these relationships strike us as having the quality of friendship, a further factor in their exhilaration for us.'

"Above all, despite the sexual attractiveness of the actors in the movies he discusses, Cavell knows that sexuality is not the ultimate secret in these marriage: 'in God's intention a meet and happy conversation is the chiefest and noblest end of marriage. Here is the reason that these relationships strike us as having the quality of friendship, a further factor in their exhilaration for us.'

"He is wise enough, moreover, to emphasize 'the mystery of marriage by finding that neither law nor sexuality (nor, by implication, progeny) is sufficient to ensure true marriage and suggesting that what provides legitimacy is the mutual willingness for remarriage, for a sort of continuous affirmation. Remarriage, hence marriage, is, whatever else it is, an intellectual undertaking.' "

Oh, how I love the idea that "a meet and happy conversation is the chiefest and noblest end of marriage"!

Some years ago, I read an article about two people in the arts (alas, I can't remember who they were) who'd been married for many, many years. Asked for the secret of their long partnership, they said: "We fell straight into conversation when we met, and we haven't come to the end of that conversation yet."

I can't think of a better model for marriage than that. Or of a narrative more romantic . . . .

July 26, 2011

Riverside

In contrast to the heat wave engulfing America, here on Dartmoor we're having a chilly, damp summer -- so when the sun breaks through the cloud cover at last, I pack my work into a knapsack, whistle for the pup, and head down to the river.

What I want is a spot where I can sit and write...

...and what Tilly wants is a spot with easy access to the water. We find a place that suits us both, and I settle down with notebooks, sketchbooks, pencils, pens, and a thermos of tea spread out on the grass around me. The pup steps into the shallows...

...her attention caught by some sheep on the opposite bank...

... and then they are forgotten in the rapturous delight of cold water on a clear, hot day.

A little farther downstream, the river forks in a roaring clash of water on stone. It's deeper here, and the rapids are strong, foaming white as milk below the cover of the trees...

...but Tilly, undaunted, dances out onto the stones as whitewater churns merrily below. Back on the bank, my heart is in my throat as I watch my fearless, fleet-footed girl...

...until she's safely back on shore at last. She gives a good shake, so that I'm wet too...

...and then the two of us walk on.

If I could hold on to this summer and this sun by strength of will alone, oh, I would never let it go -- for summer is the season, says the poet William Carlos Williams, when "the song sings itself."

As we head home, the land is singing around us: a song of light, a choir of green.

July 25, 2011

Lean In

The last issue of The New Yorker had an interesting profile of Sheryl Sandberg, one of the few female executives in Silicon Valley (formerly with Google, currently with Facebook). Although the trials and tribulations of women in corporate culture may seem far removed from a creative life in a small Dartmoor village, they are not perhaps as far removed as one might think -- for all writers and artists are small business owners, the business being Creativity, Inc., and for me (as for many others, I suspect) the business aspects of the job (sales, negotiations, contracts, book-keeping, business correspondence, etc.) take as much time and focus as actually writing, editing, and painting. Thus the business-woman side of me is always interested in other women's experiences in maintaining a healthy work/life balance.

Sandberg talks about the need for women to "sit at the table" (in other words, to show up, be present, ask for what you want), and then to "lean in" and say yes when opportunities arise (rather than leaning cautiously, politely, or fearfully back). She also talks about the need (if one is partnered or raising children) for equality in the home. "Make sure your partner is a real partner," she says -- pointing out that, statistically, in study after study, working women married to working men still do two-thirds of the housework and three-fourths of the child care.

This part of the article particularly caught my attention:

"In May, Sandberg was most concerned with the futures of the graduating class at Barnard College. She had agreed to be the commencement speaker, following Hillary Clinton in 2009, and Meryl Streep in 2010. The seniors who made up this audience for her post-feminist message were very different from the professional women who heard her TED speech. 'This probably meant more to me than any speech I've ever given, because it's the beginning of their lives,' Sandberg told me on graduation day. For four years, these women were cosseted at Barnard. 'Now they are going to start making choices. What I want to do is tell them to lean in.' She would have to do so with a voice turned husky by laryngitis. Owing to rain, the ceremony was moved from the grass at Grant's Tomb, perched above the Hudson River, to a cramped gymnasium at Columbia.

As 'Pomp and Circumstance' played, the seniors, in their powder-blue gowns and square caps, took seats in rows of folding chairs facing an elevated platform where Sandberg; Debora Spar, the president of Barnard; and other luminaries sat. Sandberg smiled and cheered when Lara Avsar, the president of the Student Government Association, said that what defines Barnard is that 'as Barnard women, we will never quit,' and then described how Barnard had changed her from a girl from Alabama who once imagined she'd now be hunting for a husband and impatient to have his children to a woman who doesn't 'have to apologize for speaking my mind.'

After hugging Spar, Sandberg approached the lectern. A colorful crimson sash was wrapped around the neck of her dark gown. Her speech, delivered without notes but with the assistance of a professional coach who worked with Sandberg on honing her delivery, made familiar points about inadequate female representation in leadership positions, about the importance of a life partner to share the responsibilities of the home, about 'leaning in' and 'do not leave before you leave.' Remember this, she said, 'You are awesome.'

She described a poster on the wall at Facebook: 'What would you do if you weren't afraid?' She said that it echoed something the writer Anna Quindlen once said, which was that 'she majored in unafraid' at Barnard. Sandberg went on, 'Don't let your fears overwhelm your desire. Let the barriers you face—and there will be barriers—be external, not internal. Fortune does favor the bold. I promise that you will never know what you're capable of unless you try. You're going to walk off this stage today and you're going to start your adult life. Start out by aiming high. . . . Go home tonight and ask yourselves, What would I do if I weren't afraid? And then go do it!'"

I love that question: What would you do if you weren't afraid? I've pinned it up on my bulletin board and have been pondering it for the last few days....

And now I ask the same question of you, women and men alike: What would you do?

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers