Terri Windling's Blog, page 174

December 15, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's Monday Tunes are dedicated to the great British songwriter and guitarist Richard Thompson:

Above, Thompson performs one of his earliest songs, "Genesis Hall," for the Songwriters Circle in 2010. (That's Suzanne Vega and Loudon Wainright III on the stage with him.) He first recorded the song when he was a member of Fairport Convention back in the 1960s, with vocals sung by the late Sandy Denny. (You can hear the Fairport version here.) As homelessness grows by leaps and bounds under our current government here in the UK, this 44-year-old song seems remarkably contemporary.

Below, Thompson performs his song "Down Where the Drunkards Roll," with backing from Vega and Wainright. Thompson first recorded the song with his ex-wife Linda Thompson on their album I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight (1974). You can hear that version here.

Above, the young Irish singer Luke Murray performs Thompson's "Beeswing" at a session on on the island of Inishbofin (Connemara, Co. Galway) in 2011. For Thompson's version, go here.

Below, the smokey-voiced Aoife O'Donovan, from Boston's Crooked Still, performs an unusually gentle version of Thompson's "1952 Vincent Black Lightning" at the Mercury Lounge in New York City, 2013. For Thompson's version, go here. (And for a quirky little bluegrass version by the Rumpke Mountain Boys, go here.)

:

Above, the American bluegrass singer Alison Krauss performs Thompson's "The Dimming of the Day" for the TransAtlantic Sessions, 2011. It's also been covered by Bonnie Rait, David Gilmour, and many others.

Below, Thompson's own version of the song, backed up by Irish singers Dolores Keane and Mary Black in a recording from 1990. It's simply gorgeous.

Bonus track: I've loved Thompson's poetic and melancholy song "Devonside" since it was first recorded in 1983, and I love it even more now that I live in Devon. Alas, I can't find a good video performance of the song, but if you care to listen to it, you'll find it here.

December 13, 2013

Gifts are meant to be passed on

"The artist's gift refines the materials of perception or intuition that have been bestowed upon him; to put it another way, if the artist is gifted, the gift increases in its passage through the self. The artist makes something higher than what he has been given, and this, the finished work, is the third gift, the one offered to the world." - Lewis Hyde (The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World)

"The artist appeals to that in us which is a gift and not an acquisition -- and, therefore, more permanently enduring. He speaks to our capacity for delight and wonder, to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives; to our sense of pity, and beauty, and pain; to the latent feeling of fellowship with all creation -- to the subtle but invincible conviction of solidarity that knits together the loneliness of innumerable hearts, to the solidarity which binds together all humanity -- the dead to the living and the living to the unborn." - Joseph Conrad (Works of Joseph Conrad, Vol. III)

"Everyone has a gift for something, even if it is the gift of being a good friend.” - Marian Anderson ("My Lord, What a Morning," Written by Herself: Autobiographies of American Women)

"There are souls in this world who have the gift of finding joy everywhere, and leaving it behind them when they go.” - Frederick William Faber (Kindness)

On the subject of "art as gift," I highly recommend Lewis Hyde's excellent book The Gift, as well as Daniel P. Smith's insightful article about Hyde ("What is Art For?"), published in the New York Times in 2008. Today's post is dedicated to my brother-of-the-heart William Todd-Jones. Happy birthday, Todd!

December 12, 2013

Growing native-born

"Until we understand what the land is, we are at odds with everything we touch. And to come to that understanding it is necessary, even now, to leave the regions of our conquest - the cleared fields, the towns and cities, the highways - and re-enter the woods. For only there can a man encounter the silence and the darkness of his own absence. Only in this silence and darkness can he recover the sense of the world's longevity, of its ability to thrive without him, of his inferiority to it and his dependence on it. Perhaps then, having heard that silence and seen that darkness, he will grow humble before the place and begin to take it in - to learn from it what it is. As its sounds come into his hearing, and its lights and colors come into his vision, and its odors come into his nostrils, then he may come into its presence as he never has before, and he will arrive in his place and will want to remain. His life will grow out of the ground like the other lives of the place, and take its place among them. He will be with them - neither ignorant of them, nor indifferent to them, nor against them - and so at last he will grow to be native-born. That is, he must reenter the silence and the darkness, and be born again." - Wendell Berry (The Art of the Commonplace)

December 11, 2013

The Gentle Art of Tramping

Robert Macfarlane wandered all across the British Isles before writing such fine books as Holloway, The Old Ways, and The Wild Places; and in this passage from the latter, he pays tribute to a kindred spirit, the Scottish writer Stephen Graham:

"Graham, who died in 1975 at the age of ninety, was one of the most famous walkers of his age. He walked across America once, Russia twice and Britain several times, and his 1923 book, The Gentle Art of Tramping, was a hymn to the wilderness of the British Isles. 'One is inclined,' wrote Graham, 'to think of England as a network of motor roads interspersed with public-houses, placarded by petrol advertisements, and broken by smoky industrial towns.' What he tried to prove with The Gentle Art, however, was that wildness was still ubiquitous.

"Graham devoted his life to escaping what he called 'the curbed ways and the tarred roads,' and he did so by walking, exploring, swimming, climbing, sleeping out, trespassing, and 'vagabonding' -- his verb -- round the world. He came at landscape diagonally, always trying to find new ways to move through them.

" 'Tramping is straying from the obvious,' he wrote, 'even the crookedest road is sometimes too straight.' In Britain and Ireland, 'straying from the obvious' brought him into contact with landscapes that were, as he put it, 'unnamed -- wild, woody, marshy.' In The Gentle Art, he described how he drew up a 'fairy-tale' map of the glades, fields and forests he reached: its networld of little-known wild places.

'There was an Edwardian innocence about Graham -- an innocence, not a blitheness -- which appealed deeply to me. Anyone who could sincerely observe that 'There are thrills unspeakable in Rutland, more perhaps than on the road to Khiva' was, in my opinion, to be cherished.

"Graham was also one one among a line of pedestrians who saw that wandering and wondering have long gone together; that their kinship as activities extended beyond their half-rhyme. And his book was a hymn to the subversive power of pedestrianism: its ability to make a stale world seem fresh, surprising and wondrous again, to discover astonishment on the terrain of the familiar."

''The adventure," Graham insisted, "is the not getting there, it is the on-the-way. It is not the expected; it is the surprise; not the fulfillment of prophecy but the providence of something better than prophesied. You are not choosing what you shall see in the world, but are giving the world an even chance to see you."

In her beautiful book Wanderlust, the American essayist Rebecca Solnit looks at the history of walking through the lens of philosophy, sociology, environmental science, politics, literature and other arts. "Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors," she observes, "disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it."

When I look at the way that Tilly takes in the world, "inside" and "outside" are alike to her, with only the annoyance of human doors between them. Nattadon Hill is home to Tilly . . . and I mean all of the hill, from top to bottom: its Commons, its woods, its tumbling streams, the brown bracken slopes, the green farmers' fields, and our warm little house on the woodland's edge. It's all home to her, both the land that is "ours" and the larger landscape that is not.

And perhaps I'm not so different from Tilly. The whole hill has become my home ground too. The concept of "home" is complex for me (being the woman that I am, with the history that I have), but the wind and rain and snow of the hill is paring that concept down to essentials:

Home is a house that I share with my loved ones. It's a landscape walked with a good black dog. It's a hill that knows my particular footsteps, and a wood where the trees all know my name. It's as simple and as solid as the earth below...but also fragile, ephemeral, therefore all the more precious. Like life itself.

My apologies for the late post. It's been that kind of day....

My apologies for the late post. It's been that kind of day....

December 9, 2013

Sometimes....

...when a bird cries out,

Or the wind sweeps through a tree,

Or the wind sweeps through a tree,

Or a dog howls in a far off farm,

I hold still and listen for a long time.

My world turns and goes back to the place

Where, a thousand forgotten years ago,

The bird and the blowing wind

Were like me, and were my brothers.

My soul turns into a tree,

And an animal, and a cloud bank.

Then changed and odd it comes home

And asks me questions. What should I reply?

Photographs above: Tilly by the Woodland Gate. Drawing: "Beauty as the Beast" by Virginia Lee.

Photographs above: Tilly by the Woodland Gate. Drawing: "Beauty as the Beast" by Virginia Lee.

December 8, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week, singer-songwriters from four countries, all influenced (in different ways) by American roots music....

Above, First Aid Kit performing their lovely tribute song, "Emmylou," at The Workman's Club in Dublin, Ireland. First Aid Kit is Johanna and Klara Söderberg, two songwriting sisters from Stockholm, Sweden.

Below, English singer-songwriter Laura Marling performing her gorgeous song "Rambling Man," at The Great Wide Open Festival in the Netherlands.

In the next video, the veteran American folk singer Lucy Kaplansky performs her poignant song "Ten Year Night" at a House Concert in Boulder, Colorado. Kaplansky grew up in Chicago, but she's been part of the Village folk scene in New York City since the late Seventies.

This song always takes me back to Arizona road trips with Howard, crossing the vast desert landscape in an old green pick-up truck, Kaplansky's Ten Year Night album playing softly on the tape deck....

Next: Two songs from the great Joan Osborne, performed for a Seattle radio station: "Work on Me" (by Osborne and Jack Petruzzelli) and "Where It's At" (by Sam Cook). She's backed up here by Keith Cotton and The Holmes Brothers.

Osborne grew up in Kentucky, and is now based, like Kaplansky, in New York.

And last:

South-African singer-songwriter Laurie Levine, recording "Time Loving You" for her fine new album, Border Crossing. (I've played Levine's music here before, but if you're unfamiliar with it, be sure to check out her terrific cover of Johnny & June Carter Cash's "Ring of Fire.")

December 6, 2013

Home is a religion

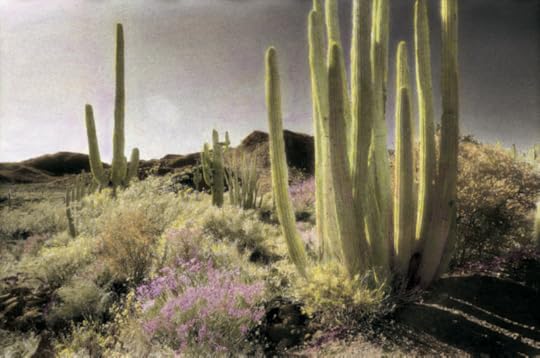

Since we're discussing the nature of "home" this week, I'm reminded of this sensuous, provocative passage from The Last Cheater's Waltz: Beauty and Violence in the Desert Southwest by Ellen Meloy:

"My geography savors a delicious paradox: Home--a grounding--found in unearthly beauty. The predominant colors are blue, emerald, and terra-cotta. Every day, every season, I taste these colors and the intricate flavors of their unaccountable tones and hues. I have yet to earn this land. Perhaps I never will. Home is a religion. Sensibly you understand the need for it, yet not even sensible people can explain it."

The pictures here are of Endicott West, an arts retreat in Tucson, Arizona, set up by Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman and me down a dusty desert road near the Rincon Mountains. In this beautiful place, numerous writers, artists, musicians, dramatists, filmmakers and many others found inspiration and a quiet environment to work in -- including me, for it was also my desert home for many years. But life moves on, things come to an end, and Endicott West is closing its doors. I'm writing a longer piece about E-West which I'll post here in a week or two. In the meantime, for me, no conversation about the meaning of "home" is complete without a nod to this most magical of shared dwellings....

December 4, 2013

More thoughts about "home"...

The places we've live, and the places we grew up in often have an impact (whether acknowledged or not) on our lives, our relationships, our dreams. . . and the houses we yearn for, whether real or imagined, reveal much about our inner nature. As a folklorist, I'm interested in how the idea of "home'"is expressed in traditional stories; and as a fantasist, in how this translates into modern magical fiction.

Fairy tales, for example often begin with a hero propelled from his or her home by poverty or calamity; and the search for the safe haven of a new home, or the task of restoring prosperity to an old one, is central to such stories. Such tales are rites–of–passage narratives, chronicling a transformational journey from one archetypal life stage to another. Most often, the tale follows a young hero's transition from childhood to adulthood, the completion of the journey symbolized by a wedding at the story's end.

Fairy tales, for example often begin with a hero propelled from his or her home by poverty or calamity; and the search for the safe haven of a new home, or the task of restoring prosperity to an old one, is central to such stories. Such tales are rites–of–passage narratives, chronicling a transformational journey from one archetypal life stage to another. Most often, the tale follows a young hero's transition from childhood to adulthood, the completion of the journey symbolized by a wedding at the story's end.

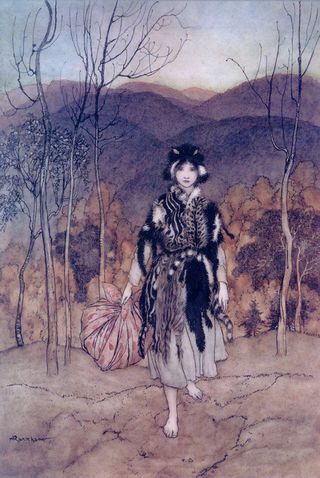

In the modern, simplified versions of the tales popularized by Disney films and children's books, the emphasis is so often placed on the romantic (and wealth accumulating) aspects of the stories that finding 'true love' (with a well heeled spouse) can seem to be what fairy tales are all about. Older, adult versions of the tales, by contrast, are focused on the steps of the hero's passage through a period of upheaval and peril — a period required to test the hero's mettle and provoke growth and self–transformation. Such tales speak to the challenges we face at any time in life (not just in our youth) when circumstances force us to leave home, either literally or metaphorically, setting us on the road to an unknown future and a new identity. Catskin, Donkeyskin, The Girl With No Hands, The Wild Swans, Hans My Hedgehog: these are all rites–of–passage narratives. Each tale begins in a childhood home that has become constricting, even dangerous, and each hero must leave this home behind in order to forge a new life in the adult world. The completion of the hero's task is marked by the traditional rewards of the fairy tale genre: a marriage, a crown, a storehold full of treasure; but the true reward at journey's end is a new–found ability to survive life's trials, transcend its terrors, and determine one's own fate.

The heroes begin in one home and end in another (or else in the old home restored and renewed), but in between these two poles is a crucial period of homelessness. Homelessness is a liminal state rich in opportunities for character change and growth, which has made it a popular plot device among storytellers both old and new. Homelessness detaches the hero from the role he or she has played in the past, strips them of identity, blurs the markers of class or rank, removes usual sources of aid and comfort, and throws them on their own resources. . .a perfect recipe for suspense, adventure, and heroic metamorphosis.

In classical myth, the home was sacred to Hestia, goddess of the hearth and perpetual flame. Sometimes called "the forgotten goddess," Hestia rarely appears in the tales of the gods, and seems to have had few temples or acolytes; and yet she was actually the first of the goddesses, sitting higher in the Olympian pantheon than even Hera (wife of Zeus, goddess of love and marriage) or Demeter (goddess of fertility and the harvest). Although avidly courted by both Poseidon and Apollo, Hestia vowed she would never marry, dedicating herself instead to the management of Mount Olympus, home of the gods. For this, she received the first portion of tribute in the temple rites of all the other gods, and was worshipped at the hearth in the center of all houses and buildings. Each morning began with Hestian prayers as the family fire was stoked for cooking and heating; each day ended with prayers to the goddess as the fire was banked for the night. Unlike the rest of the Greek pantheon, well known for their tempers, jealousies, and quarrels, Hestia was an unusually stable goddess, revered for her gentle, calm, and forgiving nature. But lest we think of her as the Olympian equivalent of a 1950s housewife, limited to home and the service of others, she was also the first builder, the inventor of architecture, and the patron of these arts.

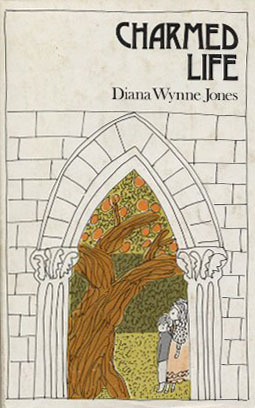

In fantasy literature, as in fairy tales, many stories begin with the loss of a home, and this is precisely what thrusts the protagonists into the world. Some stories, like L. Frank Baum's The Wizard of Oz or J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, rest on the main protagonist's fierce desire to go home again; in others, they must find or create new homes for themselves in far distant lands. In Diana Wynne Jones' Charmed Life, for  example, young Janet chooses to remain in the magical world of Chrestomanci; in Pamela Dean's "Secret Country" books, some of the children never return home again; and Austin Tappan Wright's great utopian novel Islandia revolves around a hero pulled between loyalties to his old and new countries. In fiction, as in myth, it's that in–between period of wandering and homelessness that allows for adventure and metamorphosis, propelling characters out of their settled ways of life and into their new roles as heroes. In children's fantasy, many adventures begin when a child's usual home is disrupted — when they're sent off to live with relatives, or transplanted to a summer cottage, or sent off to boarding school, etc. It's interesting to note that a number of these tales — The Owl Service by Alan Garner, for example, or The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken — were penned by writers who grew up in England during the Second World War, a time when children were regularly sent away from home to escape German bombers. Displacement, once again, creates a space that is rich in narrative possibilities, with the added bonus that once the parents are off the scene, the young protagonists are thrown onto their own resources.

example, young Janet chooses to remain in the magical world of Chrestomanci; in Pamela Dean's "Secret Country" books, some of the children never return home again; and Austin Tappan Wright's great utopian novel Islandia revolves around a hero pulled between loyalties to his old and new countries. In fiction, as in myth, it's that in–between period of wandering and homelessness that allows for adventure and metamorphosis, propelling characters out of their settled ways of life and into their new roles as heroes. In children's fantasy, many adventures begin when a child's usual home is disrupted — when they're sent off to live with relatives, or transplanted to a summer cottage, or sent off to boarding school, etc. It's interesting to note that a number of these tales — The Owl Service by Alan Garner, for example, or The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken — were penned by writers who grew up in England during the Second World War, a time when children were regularly sent away from home to escape German bombers. Displacement, once again, creates a space that is rich in narrative possibilities, with the added bonus that once the parents are off the scene, the young protagonists are thrown onto their own resources.

What I love best are those fantasy novels where the houses themselves are a source of enchantment, reminiscent of the fairy towers and haunted chateaux to be found in folk tales. The masterwork in this mini–genre is the "Gormenghast" trilogy by Mervyn Peake, in which an entire epic world is created beneath one rambling, crumbling roof, but there are plenty of other fantastical houses I'd also love to have a good wander in: such as Tamsin House from Charles de Lint's Moonheart; or Crackpot Hall from Ysabeau Wilce's Flora Segunda; or Edgewood from John Crowley's Little, Big. In such books, domestic spaces regain their aura of the numinous, connecting us, in our everyday lives, as we sleep and wake and cook and clean, to the realm of the gods, the fairies, the ancestors, and to worlds of magic.

What are your favorite magical houses in fiction, fairy tales, or myth? And what houses haunt you, real or imagined? Here are two of the real houses that I love and often dream of:

First, Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire, the country house of William Morris, his wife Jane, and Dante Grabriel Rossetti (Jane's lover) at the turn of the 19th century:

Second, Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, the country house of the painters Vanessa Bell (Virginia Woolf's sister) and Duncan Grant, in the early half of the 20th century. The house was shared, over the years, with assorted spouses, lovers, children, and Bloomsbury friends...and is now preserved by the Charleston Trust.

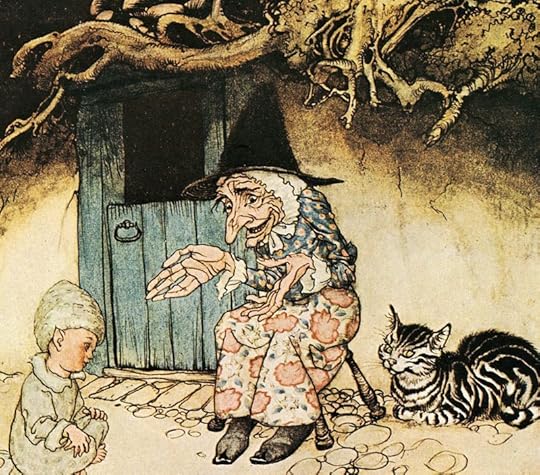

The art above is: "Dear Milie" by Maurice Sendak, "Catskin" by Arthur Rackham, "Hansel & Gretel" by Lorenzo Mattotti, "Thumbelina" by Lisbeth Zwerger, "Hans My Hedgehog" by Patricia Mignone, "Cinderella" by Edmund Dulac, a hobbit house from The Lord of the Rings Sketchbook by Alan Lee, and a "Gormenghast" painting by Alan Lee. Portions of the text here are drawn from my article "The Folklore of House and Home" (2008). For more on magical houses, visit Grace Nuth's Domythic Bliss blog. For more thoughts about "home," listen to the beautiful "Homesickness" program on Ellen Kushner's Sound & Spirit radio series.

The art above is: "Dear Milie" by Maurice Sendak, "Catskin" by Arthur Rackham, "Hansel & Gretel" by Lorenzo Mattotti, "Thumbelina" by Lisbeth Zwerger, "Hans My Hedgehog" by Patricia Mignone, "Cinderella" by Edmund Dulac, a hobbit house from The Lord of the Rings Sketchbook by Alan Lee, and a "Gormenghast" painting by Alan Lee. Portions of the text here are drawn from my article "The Folklore of House and Home" (2008). For more on magical houses, visit Grace Nuth's Domythic Bliss blog. For more thoughts about "home," listen to the beautiful "Homesickness" program on Ellen Kushner's Sound & Spirit radio series.

Thoughts about "home"

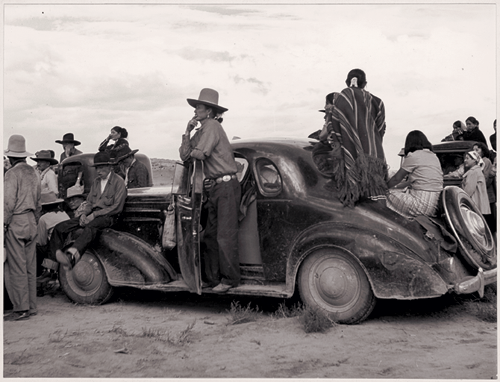

Whenever I travel (as I've done quite a bit this autumn), whether within England or further afield, it serves to remind me how essentially American I am, despite having dug my transplanted roots deep into the Devon soil. And although I grew up in the North-East, near New York, I also spent many years in the desert South-West, which seems to have permanently altered my soul. Thus I love the National Geographic's big exhibition, Photographs of the American West: 125 years of iconic photography through the lenses of 75 different photographers.

I've been reading my way through Rebecca Solnit's backlist lately, and I was struck by this passage from Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics, which says what I've so often wanted to say when conversation turns to the country of my birth:

"A year ago," she writes, "I was at a dinner in Amsterdam when the question came up of whether each of us loved his or her country. The German shuddered, the Dutch were equivocal, the Brit said he was 'comfortable' with Britain, the expatriate American said no. And I said yes. Driving now across the arid lands, the red lands, I wondered what it was I loved. The places, the sagebrush basins, the rivers digging themselves deep canyons through arid lands, the incomparable cloud formations of summer monsoons, the way the underside of clouds turns the same blue as the underside of a great blue heron's wings when the storm is about to break.

the arid lands, the red lands, I wondered what it was I loved. The places, the sagebrush basins, the rivers digging themselves deep canyons through arid lands, the incomparable cloud formations of summer monsoons, the way the underside of clouds turns the same blue as the underside of a great blue heron's wings when the storm is about to break.

"Beyond that, for anything you can say about the United States, you can also say the opposite: we're rootless except we're also the Hopi, who haven't moved in several centuries; we're violent except we're also the Franciscans nonviolently resisting nucelar weapons out here; we're consumers except the West is studded with visionary environmentalists...and the landscape of the West seems like the stage on which such dramas are played out, a space without boundaries, in which anything can be realized, a moral ground, out here where your shadow can stretch hundreds of feet just before sunset, where you loom large, and lonely.”

That's it exactly. And it's why I'll always miss the Arizona desert, despite the fact that Dartmoor is now truly home.

The idea of "home," of losing it, finding it, creating it, is a theme that often crops up in my work...not a surprising obsession, I suppose, for someone who grew up tossed between various relatives, with occasional stints in foster care. As the great Western writer Wallace Stegner once noted, in his novel Angle of Respose: "Home is a notion that only nations of the homeless fully appreciate and only the uprooted comprehend." (And yet, paradoxically, despite those fraught beginnings, I find myself blessed by strong family ties today.)

In Storming the Gates of Paradise, Rebecca Solnit writes: "The desire to go home, that is, a desire to be whole, to know where you are, to be the point of intersection of all the lines drawn through all the stars, to be the constellation-maker and the center of the world, that center called love. To awaken from sleep, to rest from awakening, to tame the animal, to let the soul go wild, to shelter in darkness and blaze with light, to cease to speak and be perfectly understood.”

Let's end today with a passage from Notes from Walnut Tree Farm by the late English naturalist Roger Deakin. I've quoted this before, but Deakin's words seem particularly relevant to the topic at hand:

"All of us," he wrote, "carry about in our heads places and landscapes we shall never forget because we have experienced such intensity of life there: places where, like the child that 'feels its life in every limb' in Wordsworth's poem 'We are seven,' our eyes have opened wider, and all our senses have somehow heightened. By way of returning the compliment, we accord these places that have given us such joy a special place in our memories and imaginations. They live on in us, wherever we may be, however far from them."

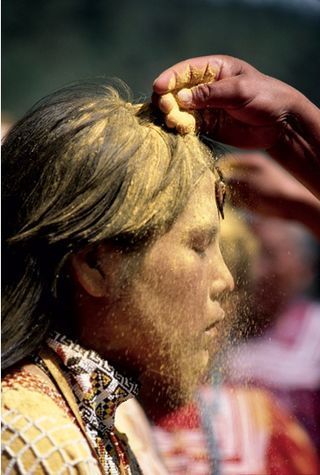

Information on the photographs can be found in the picture captions, viewed by running your cursor over each photo. Please visit the

Photographs of the American West website for more information on the exhibition.

Information on the photographs can be found in the picture captions, viewed by running your cursor over each photo. Please visit the

Photographs of the American West website for more information on the exhibition.

December 2, 2013

Thoughts upon a mid-fifties birthday....

When is one officially "old," I wonder? To me, being "old" seems to come and go, present one day and not the next. There were times as a child when I felt as old as the hills -- and there are times now when I feel like the downiest of fledgling chicks, still flapping my wings, and still just beginning.

Of the two photographs below, the first was taken when I was in Second Grade, in Manville, New Jersey; the second was snapped by my husband in our Devon garden this autumn. The Atlantic ocean, and nearly a half-century of time, stretches between the two. What surprises me is not how much I've changed during those years, but all the ways that I haven't.

Of the two photographs below, the first was taken when I was in Second Grade, in Manville, New Jersey; the second was snapped by my husband in our Devon garden this autumn. The Atlantic ocean, and nearly a half-century of time, stretches between the two. What surprises me is not how much I've changed during those years, but all the ways that I haven't.

"The great secret that all old people share," wrote Doris Lessing, "is that you really don't change in seventy or eighty years. Your body changes, but you don’t change at all. And that, of course, causes great confusion."

An old neighbor of mine, sharp and vigorous well into her nineties, would have disagreed with this, however. She felt that changing as you age is exactly the point. "The thing about growing older, dear," she once told me, "is that you don't ever stop being the age you were, you just add each new age to it. So I never envy the young, because I'm still twenty years old myself, and thirty, and forty, and so on. By the time you're my age, you have so many selves to be, and draw upon, and enjoy, that I can only feel compassion for young people, who still have so very few."

Sometimes I'm actually glad that health traumas caused me to doubt, at times, if I'd live to grow old -- for aging to me is precious and magical, and I'm grateful for it. Thus I love these words from rock-and-roller Pat Benatar's memoir (Between a Heart and a Rock Place):

"I've enjoyed every age I've been," she says, "and each has had its own individual merit. Every laugh line, every scar, is a badge I wear to show I've been present, the inner rings of my personal tree trunk that I display proudly for all to see. Nowadays, I don't want a 'perfect' face and body; I want to wear the life I've lived.”

Time writes across the body in a language that we must all come to know as we grow and age: the language of experience, loss, revelation, endurance, and mortality. Today, I'm simply thankful for the roads, dark and bright, that brought me to the miraculous present; as well as for the unknown roads, dark and bright, that still lie ahead of me. I'm another year older. I'm travelling a little slower. I carry multitudes inside. But I'm here, well-ringed like the oak trees of Nattadon Hill. And I am only just beginning.

Time writes across the body in a language that we must all come to know as we grow and age: the language of experience, loss, revelation, endurance, and mortality. Today, I'm simply thankful for the roads, dark and bright, that brought me to the miraculous present; as well as for the unknown roads, dark and bright, that still lie ahead of me. I'm another year older. I'm travelling a little slower. I carry multitudes inside. But I'm here, well-ringed like the oak trees of Nattadon Hill. And I am only just beginning.

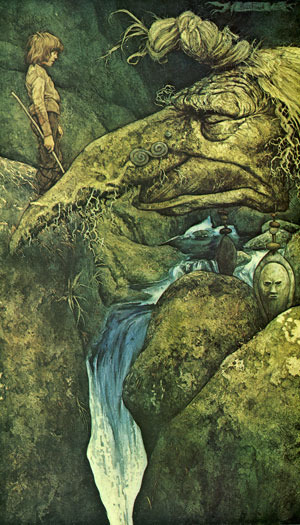

The paintings above are by Arthur Rackham and Brian Froud. The sculpture is by Fidelma Massey.

The paintings above are by Arthur Rackham and Brian Froud. The sculpture is by Fidelma Massey.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers