Rory Miller's Blog, page 3

March 17, 2017

Denying

The longest fight I have ever had lasted over an hour. At no time was I in any danger.

The thing was, we were dealing with an inmate who wanted to hurt himself. Lighten up for even an instant on pressure and he would start slamming his own head into the floor. Lose a grip on his wrist and he would try to gouge his own eyes.

In most situations-- self-defense, combatives, whatever-- you have a goal. Get to safety. Get the bad guy in cuffs. Whatever. In almost every case, the threat's goal is irrelevant to your goal. If the threat wants to play with me as a toy or see what someone looks like as they die or get enough cash for the next hit of meth or heroin or crack, that really doesn't affect my goal to get home in one piece.

Get this: most of the time your goal is NOT to deny the threat's goal. Most of the time your goal (go home safe or threat goes to jail) are antagonistic to the threat's goal purely as a side effect.

But, rarely, your goal is to deny the threat's goal. Your focus shifts from winning to denying the threat his idea of a win.

This is strategically dangerous. One of the golden rules of tactics is to never play the threat's game. But when you are trying to deny the threat his definition of the win, you've already ceded most of your strategy. There is no pro-active way to work from this paradigm. When your goal is denying the threat's goal, you have already let the threat define the goal. The threat controls the battlefield and has the advantage.

In long-term conflicts, "denying the opposition" has a more profound side-effect. Once you define yourself by your enemy, you can never win. Labor/management. Israel/Palestine. To defeat your enemy would cause your raison d'être to die. And thus, you.

Note for a future post: positive versus negative, in definition and goals.

The thing was, we were dealing with an inmate who wanted to hurt himself. Lighten up for even an instant on pressure and he would start slamming his own head into the floor. Lose a grip on his wrist and he would try to gouge his own eyes.

In most situations-- self-defense, combatives, whatever-- you have a goal. Get to safety. Get the bad guy in cuffs. Whatever. In almost every case, the threat's goal is irrelevant to your goal. If the threat wants to play with me as a toy or see what someone looks like as they die or get enough cash for the next hit of meth or heroin or crack, that really doesn't affect my goal to get home in one piece.

Get this: most of the time your goal is NOT to deny the threat's goal. Most of the time your goal (go home safe or threat goes to jail) are antagonistic to the threat's goal purely as a side effect.

But, rarely, your goal is to deny the threat's goal. Your focus shifts from winning to denying the threat his idea of a win.

This is strategically dangerous. One of the golden rules of tactics is to never play the threat's game. But when you are trying to deny the threat his definition of the win, you've already ceded most of your strategy. There is no pro-active way to work from this paradigm. When your goal is denying the threat's goal, you have already let the threat define the goal. The threat controls the battlefield and has the advantage.

In long-term conflicts, "denying the opposition" has a more profound side-effect. Once you define yourself by your enemy, you can never win. Labor/management. Israel/Palestine. To defeat your enemy would cause your raison d'être to die. And thus, you.

Note for a future post: positive versus negative, in definition and goals.

Published on March 17, 2017 02:30

March 16, 2017

No Bullshit (Virtue)

Saw an ad offering "No Bulls**t" self defense training. That's laudable. That's the goal. For that matter "No bullshit" should be a goal for training and talking and thinking and living. But it's not that simple. The no-bullshit life is a goal, but if you ever think for one second that you've achieved it, you've just started bullshitting yourself.

We all have biases-- biases in the way that we perceive, process, think, plan... You probably know some of your physical habits (when you cross your arms, is the right or the left on the outside? Are you left or right eye dominant? Which shoe goes on first?) but not all of them. You probably know even fewer of your mental habits. And even fewer of your perceptual habits (hint-- I bet if you examine the last several big meetings of strangers the handful of people you remember will have certain things in common.)

The bullshit never goes away. Humans know surprisingly little. We have a lot of stuff in our heads, but the things we know to a certainty is a very small subset. And many of those are useful, but incorrect. The sun doesn't actually rise in the East, the sun is stationary and the earth spins...and that's not true either, because the sun isn't stationary, nor is the galaxy.

I'm never certain how much bullshit has crept in. I can't be. If I only taught the things I'm 100% scientifically certain of, all of my knowledge could be summed up with "1+1=2 as long as you limit it to inanimate objects; and things with a higher number on the Mohs scale will scratch things with a lower number."

When I teach a technique, I can be fairly confidant because I've used it. But really? Take a throat strike. I've used it exactly once. Spectacularly successful. Would absolutely use it again in the same situation... but if I read a "scientific survey" trying to extrapolate from a sample of one I'd laugh my ass off.

"No Bullshit" isn't a state. It's a scale. And a process. And that makes it one of the virtues.

We tend to have a binary way of looking at the world. Is a thing good or bad? Hard or soft? Right or wrong? I find that immature. Most things are scales, not states. Not good or bad, but better or worse. End state thinking leaves no room for improvement. "Excellent" can be improved on, "perfect" can't.

If you did a move well, you can get better. If you did the same move right, you can't.

Calling something a virtue recognizes that if it is a scale, it can also be a process. Virtuous people are not the ones being good, they are the ones striving to be better. Every day. "No bullshit" as a virtue is a commitment to challenging your own assumptions, back-tracking your beliefs to first sources. It isn't the contentious skepticism of trying to prove people wrong to score points, but to cut away all of your personal wrongness to continuously build a stronger foundation.

We all have biases-- biases in the way that we perceive, process, think, plan... You probably know some of your physical habits (when you cross your arms, is the right or the left on the outside? Are you left or right eye dominant? Which shoe goes on first?) but not all of them. You probably know even fewer of your mental habits. And even fewer of your perceptual habits (hint-- I bet if you examine the last several big meetings of strangers the handful of people you remember will have certain things in common.)

The bullshit never goes away. Humans know surprisingly little. We have a lot of stuff in our heads, but the things we know to a certainty is a very small subset. And many of those are useful, but incorrect. The sun doesn't actually rise in the East, the sun is stationary and the earth spins...and that's not true either, because the sun isn't stationary, nor is the galaxy.

I'm never certain how much bullshit has crept in. I can't be. If I only taught the things I'm 100% scientifically certain of, all of my knowledge could be summed up with "1+1=2 as long as you limit it to inanimate objects; and things with a higher number on the Mohs scale will scratch things with a lower number."

When I teach a technique, I can be fairly confidant because I've used it. But really? Take a throat strike. I've used it exactly once. Spectacularly successful. Would absolutely use it again in the same situation... but if I read a "scientific survey" trying to extrapolate from a sample of one I'd laugh my ass off.

"No Bullshit" isn't a state. It's a scale. And a process. And that makes it one of the virtues.

We tend to have a binary way of looking at the world. Is a thing good or bad? Hard or soft? Right or wrong? I find that immature. Most things are scales, not states. Not good or bad, but better or worse. End state thinking leaves no room for improvement. "Excellent" can be improved on, "perfect" can't.

If you did a move well, you can get better. If you did the same move right, you can't.

Calling something a virtue recognizes that if it is a scale, it can also be a process. Virtuous people are not the ones being good, they are the ones striving to be better. Every day. "No bullshit" as a virtue is a commitment to challenging your own assumptions, back-tracking your beliefs to first sources. It isn't the contentious skepticism of trying to prove people wrong to score points, but to cut away all of your personal wrongness to continuously build a stronger foundation.

Published on March 16, 2017 09:47

March 9, 2017

Vic and Toby

...and me.

This will be (probably) the last of the MovNat AARs. Talking about training methodology.

I've written about Toby before. And here. And here. And teaching in general here. That's Toby Cowern of Tread Lightly Survival.

Wilderness survival, assault survival and movement have a lot in common. They are simultaneously complex and simple. Specifically the problems can be mind-bogglingly complex, but the solutions, in order to work, have to be simple. All three subjects are perfectly suited to the way people naturally think and move. All three subjects are almost in direct opposition to the way people are socially conditioned and taught to think and move. All three subjects wire to and work from the part of our brain that functions at primal levels with deep joy and deep pain. Almost all of civilization is specifically targeted to make these three subjects alien: We have grocery stores and central heating to avoid using wilderness survival skills; police and laws and eradicated predatory animals so we don't need assault survival and; cars and forklifts so we don't have to move and carry.

Just as there are principles in survival, and in movement, there are principles in teaching. My favorite teachers (and Vic moved onto the list) get that.

Good teaching is principles-based, and we've covered some of that in the last post.

A good teacher doesn't tell you what to think, but shows you how to think. Toby's "non-prescriptive" answers. Vic would ask the right questions, like "Where is the tension in your body? Is that helping or holding you back?" Or pointing out that if you want to move north, having your legs or feet moving west probably isn't helping.

It's about the student, not the instructor. The only reason I have any real assessment of Vic's physicality is because he attended a VioDy. At the MovNat seminar he demonstrated very little and his assistants demonstrated the minimum necessary to get you started, then the participants played. The ability of the instructor was irrelevant, the class was all about increasing the ability of the student.

At the instructor level, knowledge is insufficient. You need understanding. There was one technique in MovNat (part of the broad jump) that didn't jive with my previous training. When I asked why, the instructor (Stefano) was able to explain the reason behind the difference-- the environment in which my previous training was the right answer, why it would be right, when it would still be better than the MovNat way and the reason behind the MovNat difference. When instructors have just memorized technique, they don't have the tools to explain and are left with mere dogma. With understanding you can pass on the rules, and the exceptions, to the students.

Very little about right/wrong. Lots about better. Tied to the above point. I don't think I heard anyone being told they were doing anything wrong, but a lot of, "Try this, I think it will work better." There are lots of good teaching reasons to stay away from criticism.

And, tying into both of the last two points, there was no appeal to authority. It was all experiential. Never did Vic have to tell us something worked. When an instructor candidate pointed out a detail of your alignment or structure, there was an immediate, visible improvement. You only have to tell people something worked if it didn't actually work.

Vic was also cool with variation. I was one of the minority that had better balance with shoes on than off, and carrying a weight at chest level than at waist level. Extraordinary instructors are cool with not trying to force the statistical average onto the outliers.

Just as there is a natural movement for a human body, there is also a natural learning. Humans, like all animals, learn best through play. There's some stuff you have to talk about, and some stuff you want to play with in the gym, the studio or the lab. But playing, ideally in the real environment, is what locks in a skill. I led this post off with pointing out that some of the things closest to our evolutionary path are complex problems that require simple solutions. Play is the way we cut that Gordion knot.

This will be (probably) the last of the MovNat AARs. Talking about training methodology.

I've written about Toby before. And here. And here. And teaching in general here. That's Toby Cowern of Tread Lightly Survival.

Wilderness survival, assault survival and movement have a lot in common. They are simultaneously complex and simple. Specifically the problems can be mind-bogglingly complex, but the solutions, in order to work, have to be simple. All three subjects are perfectly suited to the way people naturally think and move. All three subjects are almost in direct opposition to the way people are socially conditioned and taught to think and move. All three subjects wire to and work from the part of our brain that functions at primal levels with deep joy and deep pain. Almost all of civilization is specifically targeted to make these three subjects alien: We have grocery stores and central heating to avoid using wilderness survival skills; police and laws and eradicated predatory animals so we don't need assault survival and; cars and forklifts so we don't have to move and carry.

Just as there are principles in survival, and in movement, there are principles in teaching. My favorite teachers (and Vic moved onto the list) get that.

Good teaching is principles-based, and we've covered some of that in the last post.

A good teacher doesn't tell you what to think, but shows you how to think. Toby's "non-prescriptive" answers. Vic would ask the right questions, like "Where is the tension in your body? Is that helping or holding you back?" Or pointing out that if you want to move north, having your legs or feet moving west probably isn't helping.

It's about the student, not the instructor. The only reason I have any real assessment of Vic's physicality is because he attended a VioDy. At the MovNat seminar he demonstrated very little and his assistants demonstrated the minimum necessary to get you started, then the participants played. The ability of the instructor was irrelevant, the class was all about increasing the ability of the student.

At the instructor level, knowledge is insufficient. You need understanding. There was one technique in MovNat (part of the broad jump) that didn't jive with my previous training. When I asked why, the instructor (Stefano) was able to explain the reason behind the difference-- the environment in which my previous training was the right answer, why it would be right, when it would still be better than the MovNat way and the reason behind the MovNat difference. When instructors have just memorized technique, they don't have the tools to explain and are left with mere dogma. With understanding you can pass on the rules, and the exceptions, to the students.

Very little about right/wrong. Lots about better. Tied to the above point. I don't think I heard anyone being told they were doing anything wrong, but a lot of, "Try this, I think it will work better." There are lots of good teaching reasons to stay away from criticism.

And, tying into both of the last two points, there was no appeal to authority. It was all experiential. Never did Vic have to tell us something worked. When an instructor candidate pointed out a detail of your alignment or structure, there was an immediate, visible improvement. You only have to tell people something worked if it didn't actually work.

Vic was also cool with variation. I was one of the minority that had better balance with shoes on than off, and carrying a weight at chest level than at waist level. Extraordinary instructors are cool with not trying to force the statistical average onto the outliers.

Just as there is a natural movement for a human body, there is also a natural learning. Humans, like all animals, learn best through play. There's some stuff you have to talk about, and some stuff you want to play with in the gym, the studio or the lab. But playing, ideally in the real environment, is what locks in a skill. I led this post off with pointing out that some of the things closest to our evolutionary path are complex problems that require simple solutions. Play is the way we cut that Gordion knot.

Published on March 09, 2017 09:47

March 7, 2017

Movement Principles

In combatives, you'll hear people talk about the principles of a system, or principles-based training. That's fine and dandy right up until you ask a senior practitioner exactly what those principles are. If you're lucky, you'll get crickets. If not, you'll get the normal word salad of someone who has been pinned down in their ignorance and needs to fill it with words. You'll get goals ("Don't get hurt.") Or strategies ("Do the maximum damage in the minimum time.") Or tactics ("Close and unbalance.") Or philosophical generalities ("Become one with your opponent.")* Basically tripe. You can't really have a good conversation about principles-based training until you've defined what principles are-- and separated them from goals, strategies, tactics and aphorisms.

There's going to be a core set of principles in any physical endeavor. One of the really gratifying things about the MovNat seminar was not just how principles-based it was but how much the principles mirrored the ones I understand.

The lists will never be exactly the same. Time doesn't function the same in a fight as it does running or climbing. Balance and gravity have other levels when you are simultaneously a bipedal creature and half of a quadrupedal creature.

Something isn't eligible for my list of principles unless it 1) fits my definition 2) applies to striking, grappling and weapons and, 3) there are no exceptions. The MovNat class with Vic pointed out that some of them applied to all movement. And that was pretty cool.

Caveat. What I am about to write comes from my perspective having taken a class once. Don't take this as anything officially MovNat-y.

Structure, momentum, balance and gravity. Four key principles and they all interact.

Life is a constant battle with gravity. Gravity is a force, and sometimes the enemy, and almost always a tool. If you need to resist gravity, resist it with bone, not muscle. That's one of the essential applications of structure. Muscle gets tired. Bone doesn't. I use structure for unbalancing and immobilizations and takedowns and... Vic used it for lifting, carrying, catching, traversing, climbing. Just that I saw. In two days.

Exploiting momentum is one of the key principles, especially when you are outmatched in size and strength. I tend to use it to make people miss and hurt themselves and fall down, but also to increase my own power. "Motion defeats strength" to quote Jimerfield sensei. Vic used it to keep motion going with less effort, to extend a jump and to slow one down and in a climbing thing--

I used to embarrass my kids when I'd take them to the playground and climb around more than they did. One of my tricks was to go to the swings. The big ones where steel poles making an inverted V on the ends to support the main beam that the swings hang from. I'd put one hand on each of the V supports and climb to the top just by swinging side to side and letting my hands move up. It was a way to climb with almost no muscle-- just structure and the momentum of the swing, which relied on gravity. Hadn't thought of that as principles until Stefano demonstrated almost the same technique for traversing.

Balance. In a lot of ways, balance is just the interplay of structure and gravity. In judo we spent a lot of time playing with the science of keeping our own balance while stealing the opponents. But there are times to lose your balance as well, times when falling serves you. Sutemi waza, for instance. Or falling on a locked elbow (someone else's). Balance is not just a principle, but a skill, and Vic had some balance games I'll be playing with for a while.

Gravity is a tool. The iconic application is the drop-step. Done properly it is a speed, power and range multiplier that doesn't telegraph. It's one of the first things I teach. Turned out to be one of the first things Vic taught as well, but as a way to effortlessly and quickly fall into a run. Or a sprint, depending on how much you commit. And a way to control your speed, without working to move your legs faster or thinking about lengthening your stride.

Still playing with thoughts from the class. Will be for awhile. Probably talk about teaching methodology next.

And, pro-tip, if you have the right partner and the right kind of post-workout smile you can get a full body tiger balm massage out of it. Awesome.

*To be fair, one of my principles is a soundbite philosophical generality, but I use it because it allows me to file a bunch of different related principles-- ranging, action/reaction speed, manipulating perception and realities of timing and distance, working in negative space, etc. all under the label "Control Space and Time."

There's going to be a core set of principles in any physical endeavor. One of the really gratifying things about the MovNat seminar was not just how principles-based it was but how much the principles mirrored the ones I understand.

The lists will never be exactly the same. Time doesn't function the same in a fight as it does running or climbing. Balance and gravity have other levels when you are simultaneously a bipedal creature and half of a quadrupedal creature.

Something isn't eligible for my list of principles unless it 1) fits my definition 2) applies to striking, grappling and weapons and, 3) there are no exceptions. The MovNat class with Vic pointed out that some of them applied to all movement. And that was pretty cool.

Caveat. What I am about to write comes from my perspective having taken a class once. Don't take this as anything officially MovNat-y.

Structure, momentum, balance and gravity. Four key principles and they all interact.

Life is a constant battle with gravity. Gravity is a force, and sometimes the enemy, and almost always a tool. If you need to resist gravity, resist it with bone, not muscle. That's one of the essential applications of structure. Muscle gets tired. Bone doesn't. I use structure for unbalancing and immobilizations and takedowns and... Vic used it for lifting, carrying, catching, traversing, climbing. Just that I saw. In two days.

Exploiting momentum is one of the key principles, especially when you are outmatched in size and strength. I tend to use it to make people miss and hurt themselves and fall down, but also to increase my own power. "Motion defeats strength" to quote Jimerfield sensei. Vic used it to keep motion going with less effort, to extend a jump and to slow one down and in a climbing thing--

I used to embarrass my kids when I'd take them to the playground and climb around more than they did. One of my tricks was to go to the swings. The big ones where steel poles making an inverted V on the ends to support the main beam that the swings hang from. I'd put one hand on each of the V supports and climb to the top just by swinging side to side and letting my hands move up. It was a way to climb with almost no muscle-- just structure and the momentum of the swing, which relied on gravity. Hadn't thought of that as principles until Stefano demonstrated almost the same technique for traversing.

Balance. In a lot of ways, balance is just the interplay of structure and gravity. In judo we spent a lot of time playing with the science of keeping our own balance while stealing the opponents. But there are times to lose your balance as well, times when falling serves you. Sutemi waza, for instance. Or falling on a locked elbow (someone else's). Balance is not just a principle, but a skill, and Vic had some balance games I'll be playing with for a while.

Gravity is a tool. The iconic application is the drop-step. Done properly it is a speed, power and range multiplier that doesn't telegraph. It's one of the first things I teach. Turned out to be one of the first things Vic taught as well, but as a way to effortlessly and quickly fall into a run. Or a sprint, depending on how much you commit. And a way to control your speed, without working to move your legs faster or thinking about lengthening your stride.

Still playing with thoughts from the class. Will be for awhile. Probably talk about teaching methodology next.

And, pro-tip, if you have the right partner and the right kind of post-workout smile you can get a full body tiger balm massage out of it. Awesome.

*To be fair, one of my principles is a soundbite philosophical generality, but I use it because it allows me to file a bunch of different related principles-- ranging, action/reaction speed, manipulating perception and realities of timing and distance, working in negative space, etc. all under the label "Control Space and Time."

Published on March 07, 2017 16:11

March 6, 2017

MovNat AAR

Spent the last two days crawling, hanging, jumping, throwing and running. And learning. It was a good time. K says I have a very specific smile when I'm tired, sore and happy.

I'm aging. And coming off of almost five years of serious leg injuries. Aerobic fitness, weight and functional power are not where I like them to be. Below my comfort zone. Legs healed to the point starting in January I could do something about it. Big headway in a short time, but still a long way to go.

Never been into the fitness community. Don't actually get into communities, period really. Went from doing ranch/homesteading work in adolescence combined with high school sports--Football, basketball and track. Then to the college judo team. Then military. That was a long string of years of good coaches and hard work. Good enough that I got the physical fitness award at both BCT and the Academy.

I have friends into fitness, particularly Myron Cossitt, Kasey Keckeisen, Matt Bellet and the Querencia crew. And I can't even follow their conversations when they get going.

At last year's VioDy Prime, one of the attendees was some French dude named Vic. Vic Verdier. Cool guy. Great physical skills, awareness, and insight. Myron was fan-boying a little on Vic (Myron does that.) After the VioDy seminar, I got an email from Vic casually asking if I'd like to attend one of his seminars. Turns out Vic is a big deal in the fitness community. MovNat.

So last weekend this middle-aged crippled up old jail guard went out to play.

It was a blast. Perfect level of intensity. If you don't hate your physical trainer a bit at the end of a session you need a new physical trainer. Next post will be about principles and cross-overs.

The movements were super basic. Fundamental. At one point we were learning a technique to lift a heavy, odd-shaped item to a shoulder carry and I was puzzled... why would this have to be taught? And I looked around the room. Almost all young (younger than me at least). Almost if not all urbanites, and I realized that probably no one else in the room had spent their childhoods lifting and carrying ninety-pound feed sacks. Or bucking alfalfa bales onto a truck.

Lifting, carrying, climbing, running, crawling, throwing-- all core, fundamental parts of being human. I'm a little weirded out they have to be taught, but some of my kid's friends have never climbed a tree.

Don't think "super-basic" or "fundamental" are in any way downplaying the value. Or the skill of the instructors. Or the thought behind the program itself. MovNat is either an introduction to or a reminder of who you are as a human animal. Some of us, maybe all of us, need that.

Vic, Stefano and Craig stressed good body mechanics. More emphasis on doing things right than doing things hard. Because there was a concurrent instructor-candidate class, each of us got a private coach as well (Thanks, Kim and Sadie!). Because of the emphasis, I was able to attend with a plethora of old injuries and, though every damn thing is sore, none of the old stuff reinjured. That's rare.

Upshot? Practical. Fun. Intense. Found some weaknesses to work on, some new diagnostic tools. It was a good weekend.

I'm aging. And coming off of almost five years of serious leg injuries. Aerobic fitness, weight and functional power are not where I like them to be. Below my comfort zone. Legs healed to the point starting in January I could do something about it. Big headway in a short time, but still a long way to go.

Never been into the fitness community. Don't actually get into communities, period really. Went from doing ranch/homesteading work in adolescence combined with high school sports--Football, basketball and track. Then to the college judo team. Then military. That was a long string of years of good coaches and hard work. Good enough that I got the physical fitness award at both BCT and the Academy.

I have friends into fitness, particularly Myron Cossitt, Kasey Keckeisen, Matt Bellet and the Querencia crew. And I can't even follow their conversations when they get going.

At last year's VioDy Prime, one of the attendees was some French dude named Vic. Vic Verdier. Cool guy. Great physical skills, awareness, and insight. Myron was fan-boying a little on Vic (Myron does that.) After the VioDy seminar, I got an email from Vic casually asking if I'd like to attend one of his seminars. Turns out Vic is a big deal in the fitness community. MovNat.

So last weekend this middle-aged crippled up old jail guard went out to play.

It was a blast. Perfect level of intensity. If you don't hate your physical trainer a bit at the end of a session you need a new physical trainer. Next post will be about principles and cross-overs.

The movements were super basic. Fundamental. At one point we were learning a technique to lift a heavy, odd-shaped item to a shoulder carry and I was puzzled... why would this have to be taught? And I looked around the room. Almost all young (younger than me at least). Almost if not all urbanites, and I realized that probably no one else in the room had spent their childhoods lifting and carrying ninety-pound feed sacks. Or bucking alfalfa bales onto a truck.

Lifting, carrying, climbing, running, crawling, throwing-- all core, fundamental parts of being human. I'm a little weirded out they have to be taught, but some of my kid's friends have never climbed a tree.

Don't think "super-basic" or "fundamental" are in any way downplaying the value. Or the skill of the instructors. Or the thought behind the program itself. MovNat is either an introduction to or a reminder of who you are as a human animal. Some of us, maybe all of us, need that.

Vic, Stefano and Craig stressed good body mechanics. More emphasis on doing things right than doing things hard. Because there was a concurrent instructor-candidate class, each of us got a private coach as well (Thanks, Kim and Sadie!). Because of the emphasis, I was able to attend with a plethora of old injuries and, though every damn thing is sore, none of the old stuff reinjured. That's rare.

Upshot? Practical. Fun. Intense. Found some weaknesses to work on, some new diagnostic tools. It was a good weekend.

Published on March 06, 2017 12:28

March 2, 2017

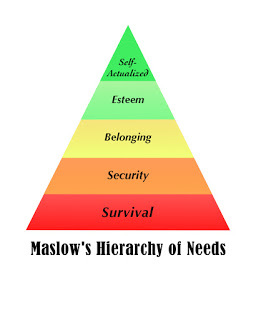

Maslow Thoughts

I use Maslow's pyramid in a lot of my books and classes. Not because it's great science, there are holes in it you can drive a truck through. I use it partially because it has great predictive power, but mostly because it is so common and universally accepted (which is not the same as 'understood') that it's easy to piggy-back useful information on it. In other words, using Maslow, you can take a person who has only ever experienced social conflict and in a few minutes get them to accept and understand the existence and even the patterns of asocial violence.

We don't work through the levels. Babies are born at the esteem level in all but the most dysfunctional families. Our ancestors took care of the two lower levels long ago. Thus, most people in the industrialized world have no frame of reference for the survival and security levels. So much so that the skills that belong there have become hobbies.

If you have a choice, it's not self-defense, it's fighting.

If you have a choice, it's not wilderness survival, it's primitive camping.

If you have a choice, it's not hunger, it's fasting.

The thought: Is it possible to have a genuine* experience of the level you inhabit without experiencing the lower levels?

Taking care of the *asterisk now. Genuine is a a problematic word. Of course anything you are experiencing you are experiencing. It's by definition genuine, as real as it is. I mean more that there is a gap between what is experienced and what could be experienced. An understanding gap. That it is different than it is perceived. (Note-- when I say the blog is where I go to think out loud, this is what it means. Words are not how I naturally think and the translation process can be ugly.)

People who have never dropped below the belonging level tend to either think that membership in a group is important without thinking why, or think it is unimportant. (This is separate from the instinctive tribal drive, I'm talking about the reasons, rationalizations and cognitive process.)

I was raised in a family of self-sufficient, back to the land, grow/hunt your own food yadda yadda yadda. I value groups because raising enough food to feed a family was a metric fuckton of manual labor. I liked being a bookworm and a dreamer, but I realized that those were self-centered, selfish preferences-- something I could indulge in during free time, but if that was all I was, someone would have to take up the slack of weeding and packing water and feeding stock and milking and chopping wood.

Same with teams. We had CERT because there were things you could do with a team efficiently and with little injury that would have been either suicidal or murderous to do alone. I still occasionally have dreams about a military service that ended 24 years ago. The bonding when you are dealing with deep Maslow problems is intense.

So I value interdependence and cooperation because of experience. It's not a knee-jerk reaction I must justify after the fact, so I see the downsides as well. Nor can I listen to the song, "I Walk Alone" without laughing a little on the inside.

If you've never experienced the survival level, there are things you can't understand (and another thought, this isn't monolithic. Look at these three examples.) If you've never been truly hungry, you can't really grasp how important food growth and distribution is or the idea that "all philosophy is based on bellies." If you've never had anyone try to kill you, physical defense skills are a fun hobby. If you've never been drowned or frozen, you'll never really grasp your own mortality, or how small you really are.

If you've never mastered the security level your basic needs are controlled by someone else. You are owned.

If you've never had to break into a group, just passed from (and this is poor kid's fantasy, I have zero experience in this world) country club family to prep school to your dad's fraternity at Yale and on to the political career assigned for you, you've never learned why other people's feeling are important or how to be considerate. You'll know the forms of politeness, because those are tribal status markers...but you'll never understand that courtesy is central to predators living together.

And without all these and putting them into play and getting competent at them, you can simulate self actualization. You can be an artist or devote yourself to causes. But the depth of understanding will be missing. Causes are chosen by the social impact on your friends. You measure your own art by the reaction provoked in others or the price you can charge for it. (Which are valid ways to evaluate art, but not self-actualized ways to evaluate your own art.)

Just a thought, and a thought I have to be careful of. Most of most best friends have depth of experience (which is the polite way to say "profoundly shitty lives"). It becomes easy to conflate 'people I like better' with 'better people,' And that's a dangerous trap.

Published on March 02, 2017 11:05

February 27, 2017

Edutainment

Snowed in a lot over the winter so getting some good reading in. For the classics, just finished Seneca's "On the Brevity of Life." Seneca may be the only Stoic so far I haven't enjoyed. Misonius Rufus is next.

Also just finished one of the best books in a long time, Tom Wainwright's Narconomics: How to Run a Drug Cartel.

It was a kick. Taking the Freakonomics approach and applying it to the world of cartels. Why violence is rampant in Mexico but has dies down in El Salvador. Why tattoos keep labor costs low. The etiquette for leaving feedback when you buy heroine on the dark web. Franchising, subcontracting and offshoring in the world of illicit drugs.

Also just finished one of the best books in a long time, Tom Wainwright's Narconomics: How to Run a Drug Cartel.

It was a kick. Taking the Freakonomics approach and applying it to the world of cartels. Why violence is rampant in Mexico but has dies down in El Salvador. Why tattoos keep labor costs low. The etiquette for leaving feedback when you buy heroine on the dark web. Franchising, subcontracting and offshoring in the world of illicit drugs.

Published on February 27, 2017 13:04

February 23, 2017

Specimen

Got to watch an interesting specimen. In retrospect, I’ve seen them before, quite a lot actually. But this one was blatant enough to draw attention. Attention brings analysis. Have to unpack the language here, and talk about a couple of categories and some background concepts.Creepers are low-level sexual predators. The kind that harass and pressure women, but always with deniability. Rarely ever cross the line into something legally actionable, or something that could legally justify physical self-defense. They stand too close, shake hands too long, try to increase the physical intimacy of a relationship (e.g. pressuring a good-bye hug from someone they just met.) It hides in the normal social interaction. Rather, they disguise it in the normal social interaction. Many are willing to apologize, to explain away, or even call in allies to make their targets feel like maybe it is all imaginary, there is no problem… Some are sophisticated enough to cultivate an image of “social awkwardness” that gets other people defending their actions: “Mel’s always like that. It’s not a gender thing he does the same weird stuff around me and the other guys.” Perfect camouflage.Most women who have been in any kind of office environment recognize the problem and know the type. But also, many excuse or explain away their own instincts.Violence groupies are all over. If you’ve been in any kind of force instruction role for any length of time, you’ve seen them. These are the guys that follow you around, begging for stories about ugly fights and death and violence. It’s not a healthy fascination, it’s pure fantasy fodder. Some of them even get fuller lips or lick their lips when they ask. Lips are erectile tissue, BTW, and swell when you get excited in certain ways. The lips are your face’s dick.The specimen this time was both.Concept: Unconsciously deliberate. People are largely unconscious machines. The words in your head are weak and pale (and very late) reflections of what is going on in your head. There’s a study out there where scientists watching an fMRI could tell what decisions a subject would make as much as six seconds before the subject consciously knew. You can pretty much get over the idea that your conscious mind is the driver.You see people clearly planning and setting up situations that they will absolutely deny were intentional. We’ve all seen it— the guy who has been married for X years and meets an interesting women and starts dropping her name into conversations with friends, starts making sure she has a place in the social network, slowly gets everyone used to her presence. Starts minimizing the wife. Then one day after a big shared victory, there will be a bottle of wine and things will “just happen…”So, back to creepers and violence groupies. You can’t accidentally stand too close or ask inappropriate questions. Those are volitional acts. But you can either be (e.g. raised in a culture with different rules on proxemics) or pretend to be oblivious that your choices are inappropriate. Watching the pattern, it may be unconscious, but the actions were one and all, deliberate.And this is an aside, but we have the idea of justice tied intimately with the idea of conscious intentionality. A planned murder is considered a more heinous act than an unplanned act of rage. As long as the creeper can convince others that there is no conscious intent, the others will believe his acts are unfortunate instead of malicious. If the creeper can convince himself, he acts guilt-free.So, and I have no answer for this— when an act is clearly deliberate, is there any way to tell if the perp was truly unconscious, pretending to himself it was unconscious or deliberately using the impression as a way to manipulate others (very conscious.) And, way to tell or not, does it matter?Two of the giveaways. The deliberate ones do target-prep. Long ago, someone introduced himself in a class I was taking as, “That guy.”“That guy?” The instructor asked.“Yeah, you know, there’s one in every class, the guy who asks the inappropriate questions and bugs the instructors.”Oh yeah. Look at that. This specimen has declared his intention to be disruptive. Any of the normal conversational response (the usual is the class snickers and the instructor says, “Thanks for letting me know,” with a little laugh and moves on) gives the specimen implicit permission. He has declared his intention, and has influenced the entire class not to object. This isn’t self-deprecating humor. This is victim grooming.When someone touts their self-awareness of their bad patterns it isn’t admirable. If they are aware of the bad patterns then any step down that path is a choice. Once you know you’re ‘that guy’ acting like ‘that guy’ is a choice. Your excuses are gone.The recent specimen had a tactic. At first I thought it was new, but in retrospect I’ve seen it before. He went around after class to apologize to the instructors. Again, the default is to be professional, polite (read ‘social and following the social scripts’) and try to minimize what he was apologizing for. But I wasn’t in a social mood.Specimen: I just wanted you to know I’m really sorry.Me: For what?Specimen: You know (very smarmy voice: Yooou knoooow)Me: I can think of a lot of things. What do you mean?Specimen: I know how I can be.Me: Then you have no excuses.Specimen: Change is hard for some people.Me: Not really.Specimen: I’ve been working on this for years...Me: Let me cut to the chase. When you say “I’m sorry” what you really mean is, “I fully intend to do the exact same things again and I want your permission.” The answer is no. You don’t get my permission.Specimen: That’s not the way I thought this conversation would go.The other giveaway: If this was subconscious, habitual, ‘just the way I am’ fear of consequences wouldn’t change behavior. More telling than the conversation I just described is his reaction afterwards. If a target sets boundaries and the creeper backs off, it may indicate an honest misunderstanding of proper behavior. Maybe. And if it is an explanation, the behavior will change universally (I once explained to a socially awkward friend the rules for shaking hands. He had assumed that the more he liked you, the longer the handshake went on and he creeped people out. Once the rules were explained his behavior improved with everyone, not just me. He is an example of someone who honestly didn’t know.)

But if someone changes behavior only around the people who simply say, “I know your game” then he knows his game as well. Deliberate and conscious.

But if someone changes behavior only around the people who simply say, “I know your game” then he knows his game as well. Deliberate and conscious.

Published on February 23, 2017 08:34

February 21, 2017

Agency and Interdependence

I recently read Junger's book, "Tribe." It hit a lot of my buttons-- not well thought out or researched, explanations just asserted even when there were far simpler possible explanations. He had a theme and a bias and stuck to them... but it got me thinking.

We live in an amazingly interdependent society. How many of you butcher your own food? Make your own clothes? Do both? Raise the cotton or wool to make the clothes? You're reading this on a machine you didn't make. Maybe, if you are really good, you assembled your own PC, but you damn sure didn't make it. Amazingly interdependent... but not really.

Societies have always been interdependent. You can think of the best survivalist societies you know-- the Kalahari Bushmen or the Lippan Apache or whatever and in all of those societies of super-survivalists, the greatest punishment was to be ostracized. Because as good as they are, no one survives for very long alone.

What's missing now is not the interdependence, it's the awareness. One side is easy to see-- the iconoclast rebel who declares himself free while typing on a keyboard (that some corporation produced) and sucking down corn chips and Mt. Dew (ditto) in his mom's basement (do I need to say ditto again?)

It's physically impossible to tweet "I'm off the grid."

Junger wrote about the other side. All of us, on some level, want to feel the interdependence. We want to feel the connection. Corny as it sounds, we want to serve.

A few of us have been trying to figure out why it seems that individual power--agency-- is so systematically denigrated in modern society.

I think there is an assumption that agency is a contrary force or contrary attitude to interdependence. It’s not. In what I consider a natural society— tribal hunter gatherers— increasing one's own agency was important for the good of the tribe. You wanted to be the bravest warrior or the most cunning hunter or the wisest healer. Change that, not ‘or’. Ideally ‘and’. So it was all about increasing agency or personal power, but for the good of the tribe.

You can look at the collectivist movements (socialism, communism, fascism) as attempts to force a tribal level of interdependence from the top down. It takes massive control because the tribes are artificial and we have enough radical ideas and different points of view that people can find their own tribes and can easily switch tribes. In order for it to work, people would need a monolithic set of values. Hence force. And failure. But those movements appeal mightily to the people looking for that sense of connection.

As wisdom (one type of power) increases, so does a recognition of interdependence as a fact. Individualists recognize that agency is not a contradiction to cooperative society. It is required if we want society to continue to improve.

At the same time, we aren't insects. We will never all have the same values or the same priorities. Nor should we. Wisdom is to let people disagree. Even more than focussing on increasing our own agency for the good of the tribe, we focus on increasing the agency of others. Accepting other people’s differences _and_ their power.

Our society tries to draw a distinction between the passive and the active-- and to include passivity in the definition of "good" (but that's a post for another day). That has resulted in the infantilaztion of adults. Screw that. Be strong. Let others be strong. Cherish their strength and your own.

Published on February 21, 2017 09:17

February 18, 2017

A New Tool

Finished a new book about a month ago, "Processing Under Pressure" by Matthew J. Sharps (link at the bottom). It had been sitting on my shelf for a long while, and I honestly don't remember if I bought a copy or if it was a gift. If it was a gift, and it was from you, thanks.

Either way, it probably wound up on my shelf because the publisher used the same stock photo for the title that my publisher did for a book I wrote, "Force Decisions." Funny, right? And also a cautionary tale about using stock photos, probably. But it was a good book. A good read and probably the best layman's introduction I've found for some of the neuroscience behind decision making and fear.

There were a lot of crossovers between Sharps book and other stuff I like, and that's always gratifying. He presented academic theories that were very close corollaries of Gordon Graham's "discretionary time." And ConCom's Monkey and Lizard. Good stuff.

There was also a tool in the book. "Feature Intensive Analysis." He didn't describe the actual process, it was more of a, 'people have a tendency to gestalt, but when you have time you will make fewer mistakes if you analyze the features of the problem.' So I let the concept sit and played with it for a bit.

Underlying background concept. Labeling, or "ist-ing" is one of the reliable signs that your monkey brain is in control. We call people names to put them in a tribe we don't have to listen to. If I call you an asshole, or any descriptor that puts you in a group, whether your political, religious or national affiliations or... it puts you outside my tribe, Which means (to my monkey brain) I don't have to listen to you. It protects me 100% from the possibility that your arguments might have merit. We all do this.

Sharps used the term gestalt as a related concept. A gestalt, traditionally, is when you see the totality of a concept. A car is thousands of little parts and each car is different, but the gestalt of "car" exists in our head as a unified thing. Professor Sharps pointed out, that just as labeling is a tool to prevent you from analysis, so is a gestalt. Whether you use the ConCom word of labeling or Sharps' interpretation of gestalt, it is a way to not think. And people are lazy. We have a definite tendency to avoid the laziness of hard thinking.

Shading into politics, one of the things that has been annoying me is the "all good or all bad" soundbite nature of most of the things I see discussed asserted. I realized these are gestalts. If I call you a "fascist" (or asshole, most people don't distinguish) I don't have to think, I'm done.

So I decided to take a stab at my own feature intensive analysis of my gestalts in politics. On one axis (sorry, talking about fascists here, forgive the pun) a list of my political labels-- communist, democrat (party), fascist, libertarian, republican (party), socialist...*

On the other axis, traits that I consider important. The features. I tried to be careful with the source of the features. For instance, I didn't use the modern academic definition of fascism but Mussolini's definition. I used Marx directly for the features of communism. For the stuff that wasn't in the literature, I used personal observation when available. If I didn't have literature or personal observation, I gave that feature a null value. If literature contradicted, I gave a null value. If observation and literature contradicted, I went with observation. For instance if a group insisted that they were for personal freedom and peace, but called for everyone who disagreed with them to be executed and planted bombed (I've just read both 'Prairie Fire' and 'Underground') they got marks for "being okay with using violence to silence their opposition."

I may not have used the FI Analysis the way Sharps intended, since I was back-engineering from a vague description of effects. But I liked it. I found it useful. It did confirm some of my gestalts, some of my impressions of how closely related some of the political labels were. But if it had been just confirming what I already believed, I'd be pretty skeptical. Like everyone else, there's a part of me that likes pre-existing beliefs validated. That's not what happened. I found a few quite unexpected similarities and differences.

And before anyone asks, no. I am not going to share the specific analysis here. 1) I didn't do it for you, I was testing a test for (to an extent) objectively testing my own instincts and, 2) There are few things more likely to put you, as a reader, in your monkey brain than to show you that your favorite affiliation is actually 80% similar to your most hated.

*Not right/left or liberal/conservative, I consider those to be a different taxonomy. I could do an FI analysis those traits, but it would be an apples-to-oranges comparison with the affiliations listed.

Either way, it probably wound up on my shelf because the publisher used the same stock photo for the title that my publisher did for a book I wrote, "Force Decisions." Funny, right? And also a cautionary tale about using stock photos, probably. But it was a good book. A good read and probably the best layman's introduction I've found for some of the neuroscience behind decision making and fear.

There were a lot of crossovers between Sharps book and other stuff I like, and that's always gratifying. He presented academic theories that were very close corollaries of Gordon Graham's "discretionary time." And ConCom's Monkey and Lizard. Good stuff.

There was also a tool in the book. "Feature Intensive Analysis." He didn't describe the actual process, it was more of a, 'people have a tendency to gestalt, but when you have time you will make fewer mistakes if you analyze the features of the problem.' So I let the concept sit and played with it for a bit.

Underlying background concept. Labeling, or "ist-ing" is one of the reliable signs that your monkey brain is in control. We call people names to put them in a tribe we don't have to listen to. If I call you an asshole, or any descriptor that puts you in a group, whether your political, religious or national affiliations or... it puts you outside my tribe, Which means (to my monkey brain) I don't have to listen to you. It protects me 100% from the possibility that your arguments might have merit. We all do this.

Sharps used the term gestalt as a related concept. A gestalt, traditionally, is when you see the totality of a concept. A car is thousands of little parts and each car is different, but the gestalt of "car" exists in our head as a unified thing. Professor Sharps pointed out, that just as labeling is a tool to prevent you from analysis, so is a gestalt. Whether you use the ConCom word of labeling or Sharps' interpretation of gestalt, it is a way to not think. And people are lazy. We have a definite tendency to avoid the laziness of hard thinking.

Shading into politics, one of the things that has been annoying me is the "all good or all bad" soundbite nature of most of the things I see discussed asserted. I realized these are gestalts. If I call you a "fascist" (or asshole, most people don't distinguish) I don't have to think, I'm done.

So I decided to take a stab at my own feature intensive analysis of my gestalts in politics. On one axis (sorry, talking about fascists here, forgive the pun) a list of my political labels-- communist, democrat (party), fascist, libertarian, republican (party), socialist...*

On the other axis, traits that I consider important. The features. I tried to be careful with the source of the features. For instance, I didn't use the modern academic definition of fascism but Mussolini's definition. I used Marx directly for the features of communism. For the stuff that wasn't in the literature, I used personal observation when available. If I didn't have literature or personal observation, I gave that feature a null value. If literature contradicted, I gave a null value. If observation and literature contradicted, I went with observation. For instance if a group insisted that they were for personal freedom and peace, but called for everyone who disagreed with them to be executed and planted bombed (I've just read both 'Prairie Fire' and 'Underground') they got marks for "being okay with using violence to silence their opposition."

I may not have used the FI Analysis the way Sharps intended, since I was back-engineering from a vague description of effects. But I liked it. I found it useful. It did confirm some of my gestalts, some of my impressions of how closely related some of the political labels were. But if it had been just confirming what I already believed, I'd be pretty skeptical. Like everyone else, there's a part of me that likes pre-existing beliefs validated. That's not what happened. I found a few quite unexpected similarities and differences.

And before anyone asks, no. I am not going to share the specific analysis here. 1) I didn't do it for you, I was testing a test for (to an extent) objectively testing my own instincts and, 2) There are few things more likely to put you, as a reader, in your monkey brain than to show you that your favorite affiliation is actually 80% similar to your most hated.

*Not right/left or liberal/conservative, I consider those to be a different taxonomy. I could do an FI analysis those traits, but it would be an apples-to-oranges comparison with the affiliations listed.

Published on February 18, 2017 22:17

Rory Miller's Blog

- Rory Miller's profile

- 133 followers

Rory Miller isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.