Beverly Akerman's Blog

March 2, 2015

On Censorship: Raziel Reid, Steven Galloway, and the Teachable Moment

The kerfuffle over the latest $25,000 Governor General Literary Award winner for children’s (text), When Everything Feels Like the Movies by Raziel Reid, illustrates a serious deficiency among Canada’s literati: despite the recent lessons of Charlie Hebdo, they apparently do not understand the definition of censorship. And perhaps even what “strong anti-gay sentiment” is.

With its boatload of vulgar words, deeds, and images—a crack pipe doubles as an anal dildo, masturbation by crucifix, immortal lines like “His thick eyelashes were so dark that it looked like he bought them at the drugstore…I fantasized about gluing them on his eyes and then ripping them off when he climaxed,” or juicy lips that look “like she had just sucked on a tampon”--not to mention its pervasive cynicism and hopelessness--there’s little doubt Reid set out to ignite a minor Mapplethorpian sensation.

Well, he got it. It started with an article by Barbara Kay, the Montreal-based National Post opinion writer of a certain age; the headline says it all: “Wasted tax dollars on a values-void novel”.

After that came criticism by Kathy Clark, an Ontario children’s writer who objected to the book’s vulgarity. A petition to the Canada Council to rescind the prize was created, with Clark the first signatory.

“I am a strong supporter of the freedom of speech and the petition does not suggest censoring the book,” Clark said. “It states that this is not quality literature and should not be rewarded as such. Raziel Reid is free to write what he wants, and I actually commend him for his intentions…in writing the book. It is the manner in which those intentions are carried out and expressed for a young audience that is at issue here.”

Reaction was swift and scathing. Vancouver writer and international bestseller Steven Galloway (The Cellist of Sarajevo, The Confabulist) attacked Clark on social media, calling her position

“disgusting…If you don’t value free speech . . . then you don’t deserve to call yourself a writer…I am ashamed of you and ashamed to share a profession with you.”

The statement has over 400 Facebook “likes.”

Incredible: Galloway, acting head of UBC’s creative writing program—and 400 of his like-minded, ostensibly freedom loving comrades--consider a petition to be censorship, an attack on freedom of speech.

Sorry, but NOT.

Here is the Canadian Oxford Dictionary (2004) on the subject (they define the noun, not the adverb):

Censor. noun. 1. an official authorized to examine printed matter, films, news, etc., before public release, and to suppress any parts on the grounds of obscenity, threats to security, etc. 2. Rom. hist. [means Roman History?] either of two annual magistrates responsible for holding censuses and empowered to supervise public morals. 3. Psych. an impulse which is said to prevent certain ideas and memories from emerging into consciousness.

So there you have it: censorship takes place when authorities—ie. those with real power-- issue fatwas, demand a book be withdrawn, remove it from schools/libraries, burn or otherwise prevent people from reading it. It would be censorship if Mr. Harper's Minister of literature turned around and said, “Take that sucker off the shelves. No one's gonna read about tampon lollipops on my watch!”

No matter how hard Galloway et al. twists it, a petition to the Canada Council to reconsider an award just doesn’t qualifies as censorship in the real world. Just to be clear, despite his many other failings, Mr. Harper, of course does not have a Minister of literature.

In these “Je suis Charlie” times, how can Galloway possibly consider a petition censorship? In a long discussion cum argument on my Facebook page over the past 10 days—where he finally admitted that dissenters to a decision have the right of appeal (ie. that the petition is part of our right to free speech and dissent), Galloway wrote this (among other ageist and insulting comments) to Barbara Kay:

You have a newspaper column. I or any one of a number of other people I will see this week could also have such a thing with one phone call. We wouldn't even need our son to be on the editorial board…Asking the Canada Council to rescind a prize for the first time in its history because it has sexual content that you and others find distasteful is so retrograde it almost baffles the mind. You don't think it's harmful, but you're approaching this from the position of an entitled, privileged white woman who has a platform to have a voice in the world…When I suggested that we would collectively like to extract your head from your rectum, it was because you are resolutely unwilling to see the world from any perspective other than your own privileged position…. I feel sorry for you, and occasionally a slight bit ashamed at myself for speaking harshly to an elderly woman.

Apparently, individual white women are not entitled to their world view. What is it called when someone is considered part of a race/class of persons, and not an individual?

But it gets worse.

In a recent Guardian interview, author Raziel Reid, Governor General Award winner for the young adult novel When Everything Feels Like the Movies, characterized the tittle of negative reaction to his book as evidence of Canada’s “strong anti-gay sentiment.”

But Canada doesn’t have a “strong anti-gay sentiment.” In fact, it’s among the most gay-friendly places extant.

In 1967 (two years before Stonewall), then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau famously opined, “There's no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation,” right before he initiated an update of the laws on abortion, divorce, and homosexuality. In 2004, Canada became the fourth nation in the world (after the Netherlands, Belgium, and Spain) to legalize same sex marriage. These days, Lonely Planet says our home and native land is “hands down the most advanced and progressive nation in the Americas for the gay community.” They single out Toronto, third on their list of “most gay friendly places on the planet…a beacon for the LGBTQ traveller in North America.”

So does a petition against the awarding of a prize to this book mean we’ve turned into a country of gay-bashers? Get a grip...When Everything Feels like the Movies

January 27, 2015

Eugenie Bouchard's twirl should make us all mad

During a post-match interview a couple of days ago at the Australian Open, Eugenie Bouchard was asked by an interviewer working for the tourney, Ian Cohen, to “give us a twirl” to show off her outfit. In the clip I saw, Ms. Bouchard looks surprised and reluctant but, at the urging of Cohen and the crowd, performs her pirouette. Then she buries her face in her hand.

Ms. Bouchard is ranked 7th in the world in her sport. Do they make these kinds of requests of male top seeds? We all know the answer to that one.

Apparently, CBC Sports’ called the incident, “very unexpected.” Other media types called it “strange” and “odd.” Egregious is more like it. Why don’t men get how awful this was?

Let me connect the dots between the disrespect shown world-class athlete Bouchard and offenses like those alleged of Jian Ghomeshi. What does the Eugenie Twirl have to do with Ghomeshi? Plenty: both events cut to the heart of our society’s unequal treatment of the sexes and of the way females are socialized in our society. We’re trained to be nice and agreeable, to “go along to get along,” rather than to be autonomous individuals with the (at times prickly) human right to draw lines in the sand, demur, and even retaliate when reasonable boundaries are crossed.

I don't condone violence, but maybe feminists have been going about the quest for equality the wrong way. Perhaps it’s time to give women the physical skills that will empower us to use a little negative reinforcement, if necessary. Knowing we’re capable of cleaning their clocks might make a big difference to the way we are treated, not to mention what we’ll put up with.

Consider the case of Jim Hounslow, according to The Toronto Star, an e-learning specialist at the Winnipeg’s Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg. He was the guy who alleged his gonads were grabbed by Ghomeshi way back when Hounslow worked for Ghomeshi while they were both studying at York University:

“With no warning, he just reached over and grabbed my genitals (through Hounslow’s jeans) and started fondling them. I was completely shocked and I reacted,” Hounslow said.

Hounslow, who is roughly the same height and build as Ghomeshi (“I am built like a cyclist and I am a cyclist”), said he grabbed Ghomeshi’s arm, pulled it behind his back and then pushed Ghomeshi hard against the elevator doors.

“I told him, ‘You are never to do that again,’” Hounslow recalls.

Contrast that to Lucy DeCoutere’s account to CBC of her alleged 2003 assault:

They started kissing consensually, but, she said, Ghomeshi soon became violent.

“He did take me by the throat and press me against the wall and choke me,” DeCoutere said. “And he did slap me across the face a couple of times.”… She left within an hour and saw Ghomeshi two more times that weekend, but they did not discuss the incident, and no further violent incidents occurred.

My point is that we (as a society) still aren’t doing enough to ensure girls and women have personal autonomy. Instead of grooming them to be strong, we groom them to be nice, by-the-rule players. Compliant, agreeable, and decorative.

No wonder we so often end up beaten and raped. I believe many people, men and even women, scoffed at reports that half of all Canadian women have been physically or sexually assaulted. But the virality of #beenrapedneverreported demonstrates that police charges truly are the tip of the iceberg.

Would the risk of being beaten up have deterred the activities of Dalhousie dental student “gentlemen’s club”?

What I want is a world where a small, cute woman is treated with as much respect as The Rock. I want a small, cute woman to be treated with respect because everyone deserves respect. But I'll take being treated with respect because of fear of a punch in the nose if that's all I (we) can get.

Women need to become more powerful as well as more empowered, and part of that means changing our approach to physical fitness, starting with youngsters. We need a revolution, the equivalent of the USA’s Title IX, here in Canada. Among other things, Title IX required American schools receiving federal funds to provide equal funds to both male and female athletic programs. We need self-defence courses, boxing, you name it. Whatever it takes to make us physically more powerful. Because the ability to write strongly worded letters clearly isn’t enough.

Most women understand why Ms. Bouchard pirouetted. Even Lucy DeCoutere’s behaviour is comprehensible, given Ghomeshi’s rainmaker status in the entertainment industry. But I think we can do more as a society to help women just say no to sexism and abuse.

Training women to be physically powerful—and aggressive as necessary—will hopefully create benefits beyond greater health and wellbeing. Done right, it will give women the confidence to say no—to the sexist treatment Ms. Bouchard experienced this week (though she, persists in calling it “funny”), to the attacks of abusers. Just say no to weak women. It’s time to go beyond slogans, and make sure our girls and women have the muscle that will make men think twice before mistreating us.

August 3, 2011

The I-Story, Part II: The Flashlight Voice, by Marko Fong

Marko Fong discusses first person present tense stories, referring to "Haircut" by Ring Lardner, "In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried" (one of my favourite short stories!) by Amy Hempel, "Pie" by yours truly, and Pam Houston's "The Best Girlfriend You Never Had".

A companion piece to his views on first person past stories, "The I-Story, An Owner's Manual."

So here, without further ado, is the link to

The I-Story, Part II: The Flashlight Voice, by Marko Fong.

And all this comes from a new blog I've just discovered, McKenna Donovan's McKenna's Way, "the official blog of To Write Well."

I first "met" Marko on Zoetrope, Francis Ford Coppolla's site. Thanks, Marko, for reading and appreciating "Pie," and placing it among such illustrious company.

Marko's bio: "Marko Fong lives in Northern California and has published first person stories (usually present tense) in Eclectica , Berg Gasse 19, Grey Sparrow Journal, Prick of the Spindle, Memoir (and), and Solstice Quarterly. His fiction has been nominated twice for a Pushcart and once for a PEN/O.Henry prize."

August 1, 2011

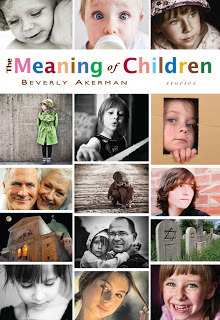

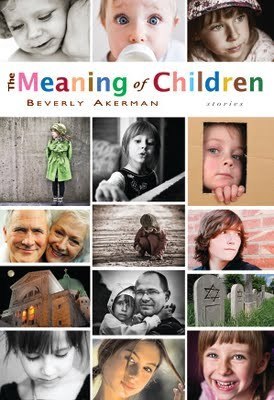

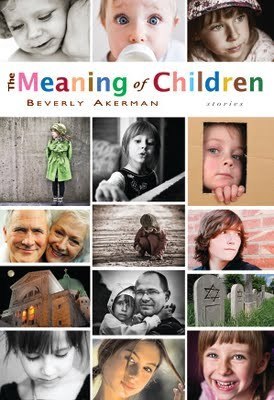

The Meaning of Children longlisted for The ReLit Award

I'm pleased to tell you my book, The Meaning Of Children, has longlisted for The ReLit Award for short fiction.

Founded by Newfoundland writer Kenneth J. Harvey, "Canada's ReLit Award--founded to acknowledge the best new work released by independent publishers--may not come with a purse, but it brings a welcome, back-to-the-books focus to the craft," says Amazon.com.

The Globe and Mail calls The ReLit Award, "The country's pre-eminent literary prize recognizing independent presses."

Shortlist due Aug. 31st, with the winners to be declared end of October, if 2010 is anything to go by.

Given annually in three genres--novel, poetry, and short fiction--the website says "winners receive the ReLit Ring, which features four moveable dials, each one struck with the entire alphabet, for spelling words."

Kenneth J. Harvey has won the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize, the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award, the Winterset Award, Italy's Libro Del Mare, and has been nominated for the Books in Canada First Novel Award, the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, and twice for both the Giller Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize. His latest book is the novel Reinventing the Rose, which The National Post called, "profoundly entertaining."

Congratulations to all the other writers named, and to Exile Editions, whose writers Anthony DiNardo, Priscila Uppal, and Meaghan Strimas were named in poetry, with Jon Papernick also longlisted for short fiction.

July 25, 2011

"Life Begins at Fifty!" New Interview, Open Book: Toronto

Writer and scientist Beverly Akerman's first book, the short fiction collection

The Meaning of Children

was recently published by Exile Editions and was just longlisted for The ReLit Award for short fiction. The book won the David Adams Richard prize in manuscript form.

Writer and scientist Beverly Akerman's first book, the short fiction collection

The Meaning of Children

was recently published by Exile Editions and was just longlisted for The ReLit Award for short fiction. The book won the David Adams Richard prize in manuscript form.Beverly Akerman talks with Open Book's Grace O'Connell (below) about her first book, the art of organizing a short fiction collection and her upcoming projects. You can find Open Book: Toronto here.

Open Book:

Open Book: Tell us about your new book, The Meaning of Children.

Beverly Akerman:Published by Exile Editions, six years in the making and soon to be a major motion picture, The Meaning Of Children is a collection of 14 short stories, divided into "Beginning" (first person point of view child stories), "Middle" (of those in the child bearing years) and "End" (stories of older people, or that take the long view of life). Many of the stories have won or placed in contests, some of them multiple times.

And I was just kidding about that movie thing. Well, more like hoping…

OB:How did it change your writing process to consider your narratives in relation to children and how they might view events?

BA:I didn't start out writing for any particular theme, beyond the issues I was interested in, felt strongly about, was moved — or even obsessed — by. Then, after four or five years, I had 25 or so published stories to my credit, and I was left to try and figure out what united them — other than the fact they were written by me. I had to package them in some sensible way. I didn't have much luck with the submission process until I hit on the current format, but you always find something in the last place you look for it… I do think writers who plan a linked or otherwise related set of stories (e.g. about people travelling the Pacific trail) will find agents and/or publishers to be receptive. But this is my first book… I had no grand plan at the outset, beyond wanting to write. And deciding that juggling the smaller universe of a short story felt way less intimidating than starting with a novel. The feedback from my readers has been pretty amazing. Touching. Heartfelt.

"I found your writing haunting and powerfully emotive, drawing on the subtleties of childhood, youth and parenthood that undermine us in strange and unexpected ways. Your writing is polished and mature, something I am always in awe of and why I got into publishing to begin with." ~ An agent at a prominent Toronto literary agency (it was a refusal, but still).

More here.

OB:

OB: How do you feel the stories in your collection interact? How do you decide on the order of the stories?

BA:That's an interesting question. We had this really compressed production schedule — only several weeks from acceptance to printing. So I read the book over a number of times in a very short period, which led me to think a lot about how the stories relate. And also to realize that they reflect the way both halves of my career intersect.

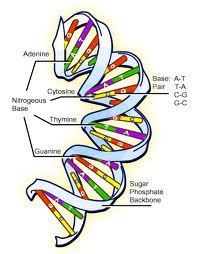

I worked for over 20 years in molecular genetics research. Now in biology and genetics, evolution by natural selection is as close to 'written in stone' as a concept can be. But the point of evolution — and selective advantage via sexual reproduction — is to produce a new generation better suited to prevailing circumstances, which change over time. And also better suited to change. So if the climate cools, for example, offspring with a warmer coat are better adapted to it and more likely to survive and go on to contribute their genes to the next generation. In other words, it's about doing your best for your offspring, albeit in an unconscious or extra-conscious way. So children are very central to all of this, or offspring, anyway, but in a very macro way. I also had three children with my husband while I was doing all that bench work, a kaleidoscope of new experiences and feelings. The stories are micro views of that.

In terms of selecting and ordering the stories, once I hit on the idea of beginning, middle, end, it all seemed much easier. I tried not to have too many of the same type of story (I had a surfeit of "middle" stories from which to choose). I wanted also to showcase different aspects of what I can do. So there's satire, there's sort of fairy tale allegory, and there's straight realism, especially in the kids-eye view stories. I would have liked a few more funny stories; a lot of my work is dark.

(One of my favourite stories is "The Hardboiled Stress of Being Santa," but I just couldn't see a place for it in the book. Also, it's so Canadian — about Brian Mulroney, Karlheinz Shriver, and scatological letters from Santa — I worried it would hurt the book elsewhere. But I'd love it if more people read it. It's on Joyland.ca but they have one of the footnote links wrong, so I'll point you to this version. Perhaps the perfect antidote to summer heat…)

Growing up can be really tough. Not so much physically, in my stories. More emotionally. That feeling children have when they realize their parents have feet of clay. If you manage it right (as a parent and maybe as a writer, too), you get growth.

OB:What recurring themes or obsessions do you notice turning up in your writing?

BA:The underappreciated world of women is my bailiwick. Loglines of several stories in The Meaning Of Children: a girl discovers a fear of heights as her parents' marriage unravels; a thirty-something venture fund manager frets over his daughter's paternity; an orphan whose hands kill whatever they touch is accused of homophobia; a suicidal daycare worker has a very bad day; a mother of two can only bear to consider abortion in the second person; the wife of a retirement-aged professor finds him unconscious near his computer. Life happens in these stories; stasis is just not an option. I write about foster kids, survivor guilt, Jewish themes; how, over time, we sometimes grow out of the lives we've painstakingly built for ourselves.

I've been told there's a lot (comparatively) of science and medicine in my work. Makes sense, as that's my background — I spent over 20 years in molecular biology labs, most of them connected with McGill University and the Montreal Children's Hospital.

OB:How do you make a character vibrant and realistic in just a few pages?

BA:Describe what they're experiencing with their senses. But not in a list… it has to be more subtle than that. The telling detail is important. The guy at the restaurant who salts his food before tasting it… does that tell you something about character? Actually, a lot of the novels I read these days seem 100 pages too long. I've heard editing is becoming a lost art, especially with 'established' writers. So I would have to say short stories are much more focused because of their length. Less flabby.

That's really the important thing: the medium requires you to cut out the unimportant details. You just don't have room for them.

OB:

OB: Who are some people who have deeply influenced your writing life?

BA:First off, I'd have to mention several of the many writers I've had as teachers: Neale McDevitt, Nancy Zafris, Luis Urrea spring immediately to mind. Wonderful writers, and amazingly generous teachers. My family, of course, who are my inspiration (in every possible way, often to their chagrin).

Then there are writers I've read: Morley Callaghan, whose The Loved And The Lost taught me when I was a very young reader that the place I lived could be interesting enough to sustain a Governor General Award-winning novel (his son Barry started Exile Editions, now run by Barry's son Michael; both these gentlemen have read my book, which feels like coming full circle). Mordecai Richler, who taught me that the best way to engage readers is to put serious themes in a comic novel. Rohinton Mistry, for demonstrating the power of a writer who loves his characters (Swimming Lessons: and other lessons from Firozsha Bagg). Lionel Shriver (We Have to Talk About Kevin, The Post-Birthday World) for being fearless and an innovator. Margaret Atwood, whose "Death by Landscape" revealed the power of even the shortest stories to haunt us. Alice Munro — I still have the copy of Lives of Girls and Women I bought at 17. Kurt Vonnegut. Harper Lee.

And last but far from least, my writing group, a wonderful gaggle of co-conspirators, who read my work and offered up their own, teaching me so much in the bargain: Pauline Clift, Julie Gedeon, Kathy Horibe, Maranda Moses and Heather Pengelley.

How much time do we have? ;)

OB:What would you say to convince someone who is "more into novels" to give short fiction a try?

BA:

BA: I'd say a couple of things. First of all, as I alluded above, short stories are a highly distilled form, a lot more focused than (many) novels. Comparing them to novels is like comparing brandy to wine. Short stories — the best short stories — are a more concentrated version, a purer hit. From the same source, yet for different purposes. From all we hear about today's shorter attention spans and more pressured lifestyles, it seems like the world is ready to rediscover short stories in a big way. They're perfect for commuting, for example. And a number of daily subscriptions on hand helds are now available (Dan Sinker's cellstories.net, currently on hiatus, published my story "Pie" twice; there's also CommuterLit).

The other main point is that short stories are often a proving ground for great new writers: Alexander MacLeod, Sarah Selecky, David Bezmozgis, Vincent Lam. So reading short stories lets you be part of discovering the next big thing. There's a certain cachet in being able to say you were among the first to appreciate them 'way back when.'

But really, diff'rent strokes for different folks.

OB:What are you working on now?

BA:I'm trying like the devil to get my collection published in the US and elsewhere. I'm figuring out how to write a novel, something set in late '60s Montreal that features the FLQ crisis. I've also been dabbling in playwriting with Colleen Curran. One of my monologues was performed at Sarasvati Productions' FemFest 2010. I keep thinking that some of my stories could be put together in film form, sort of like Raymond Carver's were in Robert Altman's Short Cuts.

There's a whole world of things out there to try. Maybe life really does begin at fifty.

Beverly Akerman is an award-winning Canadian writer and a scientist. She is strangely pleased to believe she's the only Canadian fiction writer ever to have sequenced her own DNA. You can visit her online at her website.

For more information about The Meaning of Children please visit the Exile Editions website.

Buy this book at your local independent bookstore or online at Chapters/Indigo or Amazon.

"Life Begins at Fifty!" New Interview from Open Book: Toronto

Writer and scientist Beverly Akerman's first book, the short fiction collection The Meaning of Children was recently published by Exile Editions. The book won the David Adams Richard prize in manuscript form.

Beverly Akerman talks with Open Book about her first book, the art of organizing a short fiction collection and her upcoming projects.

Open Book:Tell us about your new book, The Meaning of Children.

Beverly Akerman:Published by Exile Editions, six years in the making and soon to be a major motion picture, The Meaning Of Children is a collection of 14 short stories, divided into "Beginning" (first person point of view child stories), "Middle" (of those in the child bearing years) and "End" (stories of older people, or that take the long view of life). Many of the stories have won or placed in contests, some of them multiple times.

And I was just kidding about that movie thing. Well, more like hoping…

OB:How did it change your writing process to consider your narratives in relation to children and how they might view events?

BA:I didn't start out writing for any particular theme, beyond the issues I was interested in, felt strongly about, was moved — or even obsessed — by. Then, after four or five years, I had 25 or so published stories to my credit, and I was left to try and figure out what united them — other than the fact they were written by me. I had to package them in some sensible way. I didn't have much luck with the submission process until I hit on the current format, but you always find something in the last place you look for it… I do think writers who plan a linked or otherwise related set of stories (e.g. about people travelling the Pacific trail) will find agents and/or publishers to be receptive. But this is my first book… I had no grand plan at the outset, beyond wanting to write. And deciding that juggling the smaller universe of a short story felt way less intimidating than starting with a novel. The feedback from my readers has been pretty amazing. Touching. Heartfelt.

"I found your writing haunting and powerfully emotive, drawing on the subtleties of childhood, youth and parenthood that undermine us in strange and unexpected ways. Your writing is polished and mature, something I am always in awe of and why I got into publishing to begin with." ~ An agent at a prominent Toronto literary agency (it was a refusal, but still).

More here.

OB:How do you feel the stories in your collection interact? How do you decide on the order of the stories?

BA:That's an interesting question. We had this really compressed production schedule — only several weeks from acceptance to printing. So I read the book over a number of times in a very short period, which led me to think a lot about how the stories relate. And also to realize that they reflect the way both halves of my career intersect.

I worked for over 20 years in molecular genetics research. Now in biology and genetics, evolution by natural selection is as close to 'written in stone' as a concept can be. But the point of evolution — and selective advantage via sexual reproduction — is to produce a new generation better suited to prevailing circumstances, which change over time. And also better suited to change. So if the climate cools, for example, offspring with a warmer coat are better adapted to it and more likely to survive and go on to contribute their genes to the next generation. In other words, it's about doing your best for your offspring, albeit in an unconscious or extra-conscious way. So children are very central to all of this, or offspring, anyway, but in a very macro way. I also had three children with my husband while I was doing all that bench work, a kaleidoscope of new experiences and feelings. The stories are micro views of that.

In terms of selecting and ordering the stories, once I hit on the idea of beginning, middle, end, it all seemed much easier. I tried not to have too many of the same type of story (I had a surfeit of "middle" stories from which to choose). I wanted also to showcase different aspects of what I can do. So there's satire, there's sort of fairy tale allegory, and there's straight realism, especially in the kids-eye view stories. I would have liked a few more funny stories; a lot of my work is dark.

(One of my favourite stories is "The Hardboiled Stress of Being Santa," but I just couldn't see a place for it in the book. Also, it's so Canadian — about Brian Mulroney, Karlheinz Shriver, and scatological letters from Santa — I worried it would hurt the book elsewhere. But I'd love it if more people read it. It's on Joyland.ca but they have one of the footnote links wrong, so I'll point you to this version. Perhaps the perfect antidote to summer heat…)

Growing up can be really tough. Not so much physically, in my stories. More emotionally. That feeling children have when they realize their parents have feet of clay. If you manage it right (as a parent and maybe as a writer, too), you get growth.

OB:What recurring themes or obsessions do you notice turning up in your writing?

BA:The underappreciated world of women is my bailiwick. Loglines of several stories in The Meaning Of Children: a girl discovers a fear of heights as her parents' marriage unravels; a thirty-something venture fund manager frets over his daughter's paternity; an orphan whose hands kill whatever they touch is accused of homophobia; a suicidal daycare worker has a very bad day; a mother of two can only bear to consider abortion in the second person; the wife of a retirement-aged professor finds him unconscious near his computer. Life happens in these stories; stasis is just not an option. I write about foster kids, survivor guilt, Jewish themes; how, over time, we sometimes grow out of the lives we've painstakingly built for ourselves.

I've been told there's a lot (comparatively) of science and medicine in my work. Makes sense, as that's my background — I spent over 20 years in molecular biology labs, most of them connected with McGill University and the Montreal Children's Hospital.

OB:How do you make a character vibrant and realistic in just a few pages?

BA:Describe what they're experiencing with their senses. But not in a list… it has to be more subtle than that. The telling detail is important. The guy at the restaurant who salts his food before tasting it… does that tell you something about character? Actually, a lot of the novels I read these days seem 100 pages too long. I've heard editing is becoming a lost art, especially with 'established' writers. So I would have to say short stories are much more focused because of their length. Less flabby.

That's really the important thing: the medium requires you to cut out the unimportant details. You just don't have room for them.

OB:Who are some people who have deeply influenced your writing life?

BA:First off, I'd have to mention several of the many writers I've had as teachers: Neale McDevitt, Nancy Zafris, Luis Urrea spring immediately to mind. Wonderful writers, and amazingly generous teachers. My family, of course, who are my inspiration (in every possible way, often to their chagrin).

Then there are writers I've read: Morley Callaghan, whose The Loved And The Lost taught me when I was a very young reader that the place I lived could be interesting enough to sustain a Governor General Award-winning novel (his son Barry started Exile Editions, now run by Barry's son Michael; both these gentlemen have read my book, which feels like coming full circle). Mordecai Richler, who taught me that the best way to engage readers is to put serious themes in a comic novel. Rohinton Mistry, for demonstrating the power of a writer who loves his characters (Swimming Lessons: and other lessons from Firozsha Bagg). Lionel Shriver (We Have to Talk About Kevin, The Post-Birthday World) for being fearless and an innovator. Margaret Atwood, whose "Death by Landscape" revealed the power of even the shortest stories to haunt us. Alice Munro — I still have the copy of Lives of Girls and Women I bought at 17. Kurt Vonnegut. Harper Lee.

And last but far from least, my writing group, a wonderful gaggle of co-conspirators, who read my work and offered up their own, teaching me so much in the bargain: Pauline Clift, Julie Gedeon, Kathy Horibe, Maranda Moses and Heather Pengelley.

How much time do we have? ;)

OB:What would you say to convince someone who is "more into novels" to give short fiction a try?

BA:I'd say a couple of things. First of all, as I alluded above, short stories are a highly distilled form, a lot more focused than (many) novels. Comparing them to novels is like comparing brandy to wine. Short stories — the best short stories — are a more concentrated version, a purer hit. From the same source, yet for different purposes. From all we hear about today's shorter attention spans and more pressured lifestyles, it seems like the world is ready to rediscover short stories in a big way. They're perfect for commuting, for example. And a number of daily subscriptions on hand helds are now available (Dan Sinker's cellstories.net, currently on hiatus, published my story "Pie" twice; there's also CommuterLit).

The other main point is that short stories are often a proving ground for great new writers: Alexander MacLeod, Sarah Selecky, David Bezmozgis, Vincent Lam. So reading short stories lets you be part of discovering the next big thing. There's a certain cachet in being able to say you were among the first to appreciate them 'way back when.'

But really, diff'rent strokes for different folks.

OB:What are you working on now?

BA:I'm trying like the devil to get my collection published in the US and elsewhere. I'm figuring out how to write a novel, something set in late '60s Montreal that features the FLQ crisis. I've also been dabbling in playwriting with Colleen Curran. One of my monologues was performed at Sarasvati Productions' FemFest 2010. I keep thinking that some of my stories could be put together in film form, sort of like Raymond Carver's were in Robert Altman's Short Cuts.

There's a whole world of things out there to try. Maybe life really does begin at fifty.

Beverly Akerman is an award-winning Canadian writer and a scientist. She is strangely pleased to believe she's the only Canadian fiction writer ever to have sequenced her own DNA. You can visit her online at her website.

For more information about The Meaning of Children please visit the Exile Editions website.

Buy this book at your local independent bookstore or online at Chapters/Indigo or Amazon.

July 20, 2011

The Meaning Of Children Scores Another Lovely Review (this time from Newfoundland)

"If, as Dostoevsky once remarked, and as is quoted on the collection's frontispiece, 'The soul is healed by being with children,' it is the tragedy of adulthood that we become so isolated from childhood — and what children offer us. Artfully, evocatively, Beverly Akerman's 'The Meaning of Children' reminds us of that."

~Darrell Squires, The Western Star, Corner Brook NL

You can read the entire review here.

July 18, 2011

From alpha globin genes to short story magazines: Singularity Magazine (May 2011)

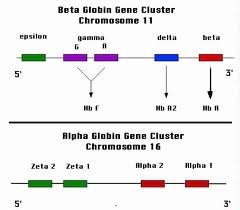

1) Before we talk about your book, The Meaning of Children, tell us more about your work in molecular genetics research.

I did my McGill University MSc with Charles Scriver at the Debelle Laboratory for Biochemical Research, which is a department in The Montreal Childrens' Hospital. The title of my thesis was Alpha Globin Genes in Quebec Populations. Adult hemoglobin is made of two chains, so-called alpha and beta (two of each, actually).  Hereditary anemias—like thalassemia and sickle cell anemia—are caused by mutations (which can be point mutations or deletions) in either gene. Because the normal person actually has 4 copies of the alpha gene (two from each parent), most alpha mutations are due to deletions. So basically I used Southern blotting to analyze how many alpha globin genes there were in people from Quebec groups at varying risk for hereditary anemia. My thesis was deposited in 1987, before PCR technology became widely used. My first job was in Nahum Sonenberg's lab in McGill's biochemistry department. He focused on translation initiation; that's where I became really proficient in DNA cloning and sequencing. From there, I worked with Roy Gravel (who had just come from University of Toronto to head up the MCH's Research Institute; '90-'96).

Hereditary anemias—like thalassemia and sickle cell anemia—are caused by mutations (which can be point mutations or deletions) in either gene. Because the normal person actually has 4 copies of the alpha gene (two from each parent), most alpha mutations are due to deletions. So basically I used Southern blotting to analyze how many alpha globin genes there were in people from Quebec groups at varying risk for hereditary anemia. My thesis was deposited in 1987, before PCR technology became widely used. My first job was in Nahum Sonenberg's lab in McGill's biochemistry department. He focused on translation initiation; that's where I became really proficient in DNA cloning and sequencing. From there, I worked with Roy Gravel (who had just come from University of Toronto to head up the MCH's Research Institute; '90-'96).  He worked on gangliosidoses—I published work on Tay Sachs disease mutations in non-Jewish populations. And from there, it was back to work with Charles and also Dr. Eileen Treacy ('96-99). I spent 10 months in the lab of Andrea Leblanc at the Lady Davis Institute—working on enzymes involved in programmed cell death, called caspases. From there, I headed off to the private sector, to a now-merged biotech company called Ecopia. They were looking for new antibiotics by scanning bacterial genomes. After three years there, molecular biology and I called it quits.

He worked on gangliosidoses—I published work on Tay Sachs disease mutations in non-Jewish populations. And from there, it was back to work with Charles and also Dr. Eileen Treacy ('96-99). I spent 10 months in the lab of Andrea Leblanc at the Lady Davis Institute—working on enzymes involved in programmed cell death, called caspases. From there, I headed off to the private sector, to a now-merged biotech company called Ecopia. They were looking for new antibiotics by scanning bacterial genomes. After three years there, molecular biology and I called it quits.

2) You sequenced your own DNA. What made you do it? More importantly, how did you go about doing it? Can everyone do it too?

I needed a control for a Tay Sachs disease patient whose DNA I was sequencing, so I used my own (probably not a good idea but people do that all the time, or at least did so back then). I don't think you could do this at home: for one thing, in those days, you needed to use radioactive material. So ordering it and using it safely meant doing it in a laboratory. And it was only short segments of my DNA, not all of it. But it is a true quirky fact that I've done it, so it amuses me to include it as part of my biography.

3) Moving from molecular genetics to fiction writing seems like a big jump. What's the story behind it?

Well, I think I had been moving beyond science for a decade, but gradually. Then something really acute happened: my father-in-law, Gerry Copeman, died of lung cancer in 2003. Gerry and I didn't get along that well, though we'd made our peace. But when he died, I was plunged into a sort of crisis: I understood—emotionally, as opposed to rationally or intellectually—that my time on this earth was finite, and that I'd better use it doing something I'd always dreamed of doing—which was writing fiction. So I quit working in science and started writing. I have a wonderfully supportive family.

4) The short stories in your book all revolve around children. What's the significance?

I didn't start out to write stories on any particular theme, beyond that they were about issues that I was interested in, felt strongly about, was moved by. Then, after four or five years, I had written all these stories and I had to find a way to unite them, to put them into a package in some way that made sense other than that they were written by me. I ended up with a book that has three parts—Beginning (which features first-person point of view stories of children), Middle (stories of people in the child-bearing years), and End (which features older people, or stories that take the long view of life). I've also been thinking a lot lately of where my two careers intersect. In biology and genetics, evolution by natural selection is as close to written in stone as any concept. But the point of evolution—and selective advantage via sexual reproduction—is to produce a 'better' next generation, one more suited to the prevailing circumstances. In other words, it's about doing your best for your offspring, albeit in an unconscious or extra-conscious way. So children are very central to all of this, or offspring, anyway.  I also had three children with my husband while I was doing all that lab work. I've been intrigued to experience all those parental feelings on a personal level.

I also had three children with my husband while I was doing all that lab work. I've been intrigued to experience all those parental feelings on a personal level.

5) Of all the 14 short stories, which one did you find the hardest to write? Why is that?

The hardest ones are the ones that aren't published yet. Probably because I have yet to get them right!

6) If you had to write a children's book, instead of a book revolving around children, what is the first idea and storyline you think of?

I'd love to write more funny stuff, so I'd want to write something about misunderstandings or kids getting into mischief. Science mischief, maybe, I hadn't thought of that before, so thanks for this. I feel that I may have written too many sad or dark stories. Maybe I just had to get them out of my system, though.

7) Where can we get more information about you and your book?

You can read about my triumphs and tribulations by finding me on Facebook, 'liking' my book's Facebook page, or on Twitter at @Beverly_Akerman.

Transitioning from alpha globin genes to short story prizewinning: my interview in Singularity Magazine (May 2011)

Vincent Tan of Singularity Magazine (the magazine "for curious artists and scientists") was kind enough to interview me for his May 2011 issue...thanks again, Vincent!!

1) Before we talk about your book, The Meaning of Children, tell us more about your work in molecular genetics research.

I did my McGill University MSc with Charles Scriver at the Debelle Laboratory for Biochemical Research, which is a department in The Montreal Childrens' Hospital. The title of my thesis was Alpha Globin Genes in Quebec Populations. Adult hemoglobin is made of two chains, so-called alpha and beta (two of each, actually). Hereditary anemias—like thalassemia and sickle cell anemia—are caused by mutations (which can be point mutations or deletions) in either gene. Because the normal person actually has 4 copies of the alpha gene (two from each parent), most alpha mutations are due to deletions. So basically I used Southern blotting to analyze how many alpha globin genes there were in people from Quebec groups at varying risk for hereditary anemia. My thesis was deposited in 1987, before PCR technology became widely used. My first job was in Nahum Sonenberg's lab in McGill's biochemistry department. He focused on translation initiation; that's where I became really proficient in DNA cloning and sequencing. From there, I worked with Roy Gravel (who had just come from University of Toronto to head up the MCH's Research Institute; '90-'96).  He worked on gangliosidoses—I published work on Tay Sachs disease mutations in non-Jewish populations. And from there, it was back to work with Charles and also Dr. Eileen Treacy ('96-99). I spent 10 months in the lab of Andrea Leblanc at the Lady Davis Institute—working on enzymes involved in programmed cell death, called caspases. From there, I headed off to the private sector, to a now-merged biotech company called Ecopia. They were looking for new antibiotics by scanning bacterial genomes. After three years there, molecular biology and I called it quits.

He worked on gangliosidoses—I published work on Tay Sachs disease mutations in non-Jewish populations. And from there, it was back to work with Charles and also Dr. Eileen Treacy ('96-99). I spent 10 months in the lab of Andrea Leblanc at the Lady Davis Institute—working on enzymes involved in programmed cell death, called caspases. From there, I headed off to the private sector, to a now-merged biotech company called Ecopia. They were looking for new antibiotics by scanning bacterial genomes. After three years there, molecular biology and I called it quits.

2) You sequenced your own DNA. What made you do it? More importantly, how did you go about doing it? Can everyone do it too?

2) You sequenced your own DNA. What made you do it? More importantly, how did you go about doing it? Can everyone do it too?

I needed a control for a Tay Sachs disease patient whose DNA I was sequencing, so I used my own (probably not a good idea but people do that all the time, or at least did so back then). I don't think you could do this at home: for one thing, in those days, you needed to use radioactive material. So ordering it and using it safely meant doing it in a laboratory. And it was only short segments of my DNA, not all of it. But it is a true quirky fact that I've done it, so it amuses me to include it as part of my biography.

3) Moving from molecular genetics to fiction writing seems like a big jump. What's the story behind it?

Well, I think I had been moving beyond science for a decade, but gradually. Then something really acute happened: my father-in-law, Gerry Copeman, died of lung cancer in 2003. Gerry and I didn't get along that well, though we'd made our peace. But when he died, I was plunged into a sort of crisis: I understood—emotionally, as opposed to rationally or intellectually—that my time on this earth was finite, and that I'd better use it doing something I'd always dreamed of doing—which was writing fiction. So I quit working in science and started writing. I have a wonderfully supportive family.

4) The short stories in your book all revolve around children. What's the significance?

I didn't start out to write stories on any particular theme, beyond that they were about issues that I was interested in, felt strongly about, was moved by. Then, after four or five years, I had written all these stories and I had to find a way to unite them, to put them into a package in some way that made sense other than that they were written by me. I ended up with a book that has three parts—Beginning (which features first-person point of view stories of children), Middle (stories of people in the child-bearing years), and End (which features older people, or stories that take the long view of life). I've also been thinking a lot lately of where my two careers intersect. In biology and genetics, evolution by natural selection is as close to written in stone as any concept. But the point of evolution—and selective advantage via sexual reproduction—is to produce a 'better' next generation, one more suited to the prevailing circumstances. In other words, it's about doing your best for your offspring, albeit in an unconscious or extra-conscious way. So children are very central to all of this, or offspring, anyway.  I also had three children with my husband while I was doing all that lab work. I've been intrigued to experience all those parental feelings on a personal level.

I also had three children with my husband while I was doing all that lab work. I've been intrigued to experience all those parental feelings on a personal level.

5) Of all the 14 short stories, which one did you find the hardest to write? Why is that?

The hardest ones are the ones that aren't published yet. Probably because I have yet to get them right!

6) If you had to write a children's book, instead of a book revolving around children, what is the first idea and storyline you think of?

I'd love to write more funny stuff, so I'd want to write something about misunderstandings or kids getting into mischief. Science mischief, maybe, I hadn't thought of that before, so thanks for this. I feel that I may have written too many sad or dark stories. Maybe I just had to get them out of my system, though.

7) Where can we get more information about you and your book?

You can read about my triumphs and tribulations by finding me on Facebook, 'liking' my book's Facebook page, or on Twitter at @Beverly_Akerman.

July 16, 2011

Author! Author! An Interview with Beverly Akerman

After over two decades in molecular genetics research, Beverly Akerman realized she'd been learning more and more about less and less. Skittish at the prospect of knowing everything about nothing, she turned, for solace, to writing. The results are impressive: She's been nominated for the Pushcart Prize (fiction and nonfiction) and National Magazine Awards. Her credits include Maclean's Magazine, The Toronto Star, The National Post, The Montreal Gazette and CBC Radio One's Sunday Edition, myriad literary and scientific journals and other publications. And, now, she has a collection of short stories titled The Meaning of Children, published with Exile Editions.

In The Meaning of Children, Beverly presents us with 14 stories that approach the world's complexities through a child's eyes (Beginning), grapple with the sorrows and ecstasies of the child-bearing years (Middle), and probe truths that emerge near the end of life's journey (End). The Meaning of Children speaks to all of us who—though aware the world can be a very dark place—can't help but long for redemption.

You are a master story teller Beverly. What, in your opinion, makes a great short story and what did you have to pay attention to as a writer?

Everyone's time is precious, particularly my reader's. So if I want people to read something I've written, there has to be something in it for them. Like, a good story.

I write literary fiction (or try to), but I think some readers (and writers!) have decided that means stories where nothing much happens. Well, in my stories, the kernel is an event that creates a significant emotional response in the reader. I don't want to spend all my time in a character's head when I'm reading a book myself, so I'm not going to write stories where the protagonist spends all her time moaning and groaning about her lot. I don't believe in anomie. I don't believe in books about nothing more than young people f*cking.

Emotion is important and at the crux of everything. So emotional experiences matter. Paring down the prose matters. Beginning, middle, end. The character has to change (or miss a grand opportunity for growth, and the reader has to know that.

Getting a book of short stories published with a prestigious publisher like Exile Editions is everyone's dream. Tell us a bit about getting them on board.

I'm really pleased to be published by Exile for a number of reasons. They're a small literary publisher with a solid gold reputation—they've published some of the great writers of our time— Yehuda Amichai , Pablo Neruda , Morley Callaghan , Austin Clarke , Lauren B. Davis , Michael Moriarty , Joyce Carol Oates , Boris Pasternak , to name a few. But the secret reason I'm thrilled with Exile (I'm a diaspora Jew—even the name "Exile" pleases me!) is that it was founded by Barry Callaghan, who is Morley Callaghan's son. The current publisher is Michael Callaghan, Barry's son and Morley's grandson.

But that's not the secret.

The secret is that Morley Callaghan is fundamental to my having become a writer. And in more ways than one.

First of all, his 1951 masterpiece, The Loved and The Lost, has always stuck with me. This great novel of the immorality of racism takes place in Montreal , and the protagonist is a man named Jim McAlpine. TLATL is one of the first CanLit novels I remember reading as a really young person. My last science job ended in 2003, when I left a biotech company called Ecopia. Some time during the last year or so that I worked there, a new VP was recruited from the States, a man named Jim McAlpine.

"A day is full of possibilities… " Beverly says. (Photo taken by author in Ogunquit, Maine)

"A day is full of possibilities… " Beverly says. (Photo taken by author in Ogunquit, Maine)Now I hadn't thought of TLATL for years, but the moment I heard the new VP's name, my first thought was, "that's the name of Callaghan's protagonist in TLATL." I dug up my old copy of the book and brought it into work, where it sat in my desk drawer for months (I never worked up the nerve to show the biochemist Jim McAlpine; I figured he'd think I was a loon!). Every time I caught sight of it, I puzzled over the coincidence of the names and why it meant so much to me. Eventually, I realized that I had to quit science because what I really wanted to do was write.

So Morley Callaghan taught me two absolutely vital things: that the place I lived could be interesting enough to sustain a Governor General Award-winning novel—remember, this was before I'd ever read anything by Richler!—and that a novel I hadn't looked at for a couple of decades still meant that much to me.

There was one more really fundamental thing that put me on the path to being a writer: the death of my father-in-law, Gerry Copeman. Gerry and I didn't get along that well, though we'd made our peace. But when he died, I plunged into a crisis: I understood—emotionally, as opposed to rationally or intellectually—that my time on this earth was finite, and I'd better use it doing something I'd always dreamed of doing—which was writing fiction.

Let me take another stab at answering your question, though. I submitted to Exile more than once. I just kept at it. They had my manuscript for close to 2 years, without a contract. The length of time I found very trying, I can't deny it. But, if there's a message here, it's to believe in your work and not give up.

And, by the way, as far as submitting short stories goes, I submitted like mad. And I pretty much completely disregarded any demands not to submit simultaneously—that is, I submitted each story to many lit journals at the same time. That's supposed to be a no-no. But really, if I needed to face 10 rejections before an acceptance (and that'd be an easy road for most of my stories!), and each journal took six months to answer me, that'd be five years before I got a story accepted…at that rate, I'd've been DEAD before having a significant body of stories in print!

Reprinted, with kind permission, from SandraPhinney.com.