Peter Labrow's Blog, page 5

February 21, 2011

Retelling the Tell-Tale Heart

I think perhaps that audiobooks have something of stigma attached. I can understand this – and to some extent agree with it. The narrator can get in the way of the narrative if he/she isn't suitable for the title. It's easy for the narrator to overdo (or understate) the story – in fact, it's pretty hard to tell a good story verbally. And then there's that nasty business of abridging – in my book, a euphemism for 'chopping the heart out of'.

Real readers want real books, the way the writer intended.

Yet, storytelling has a long tradition; far longer than the printed word. It's how stories were first handed down. If you've not been to a storytelling event, I very much recommend Festival at the Edge, a weekend of tales long and short, a little music and (if you're like me) quite a bit of beer. Enjoying stories socially – and even interacting with the reader – can seem a little odd, but it's remarkably enjoyable.

So in the end, I have to dismiss prejudice against the audiobook in the same way I do prejudice against the comic book. Just because it's not printed prose, doesn't mean it's not a valid way to tell the tale.

And so, after that preamble, onto an audiobook I've just finished, Edgar Allan Poe – The Pit and the Pendulum.

I don't often listen to audiobooks – I guess for the reasons stated above: I hate abridged content with a vengeance and I find that narrators want to showcase themselves and not the story. Not so with this audiobook.

And Poe – goodness, that's hallowed ground. Poe is one of my favourite authors and, over one hundred and fifty years after his death, his style of writing can easily come across as hammy and pseudo-gothic in the wrong hands.

Add to that the choice of narrator – David Soul? Surely he's a bit, well, lightweight?

My misgivings were entirely misplaced. Soul is the perfect narrator. I'm going to go out on a limb, too. If, like me, you were entranced by James Mason's rendition of The Tell-Tale Heart, there's a real worry that nothing will come close. But not only does Soul come close, in my book he entirely surpasses Mason. Soul's voice may not be as distinctive as Mason's but the reading is all the better for it – and it's every bit as intense and expressive. Immediately after listening to Soul, I went back to the Mason recording and was surprised at how many places his reading is misjudged. Soul manages to hold back, just the right amount – and yet squeezes from each line exactly the right level of delivery. He does exactly what a great storyteller should do: fade just enough into the background so that his voice creates the pictures in your mind. He's showcasing Poe, not himself. Each tale is a superb reading from end to end.

Each of the stories is delivered with equal skill: The Pit and the Pendulum, The Masque of the Red Death, The Tell-Tale Heart, The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar and Hop-Frog. And of course, the content is unabridged. Well, who would have the nerve to edit Poe?

Soul's narration is underpinned by excellent music and sound effects. Director Barnaby Edwards has been responsible for plenty of full-cast audio plays; this experience shows when bringing into the narrative elements which don't strictly belong there. Sound effects and music are there to support the narrator, not to overpower him. Some of this stuff is very subtly done – a wonderful experience when wearing headphones in the dark.

Clearly, this work has been directed by someone who isn't just out to cash in on Poe: he understands his work and respects it thoroughly. It's as much a labour of love as it is a commercial venture.

Is the release missing anything? I asked Barnaby Edwards about the lack of The Raven and he told me that a release of Poe's poetry is on his mind. (You can follow Barnaby on Twitter as well as his audio company Textbook Stuff.)

If you love Poe do take some time to seek out this superb – and possibly definitive – retelling of some of Poe's best tales. You won't be disappointed. (If you love horror, you'll also be pleased to note that Textbook Stuff has also released titles by MR James, Charles Dickens and Bram Stoker.)

The company is also using social funding to raise money to produce Sheridan Le Fanu's Camilla. You can donate here to make this great project happen.

Filed under: Uncategorized

February 20, 2011

Using Scrivener to create e-books

I was reading an excellent blog today by writer and Scrivener user David Hewson about Why Apple and publishing don't mix. In fact, it was David's enthusiasm for Scrivener which first tempted me to try it – and, before I move on, David's blog is one of the best 'blogs on writing' out there.

David had spotted something I'd missed in Scrivener 2 – the fact that it can output directly to a range of e-book formats.

This had me immediately excited. When I published The Well, I created the Kindle and ePub files by coding the XHTML/XML directly. I just wasn't happy with the output of the various tools available.

I did enlist the help of Mobipocket Creator and Sigil along the way. Both have strengths, but you still need to do some manual tweaking of the XHTML/XML at the very least. But they are yet another step in the publishing process. Because there isn't one e-book standard, I've had to create files from InDesign (PDF for print) and a Kindle file for Amazon along with an ePub for Adobe Digital Editions and other platforms which support that format. It was complex and time-consuming, hence the excitement when I spotted the export facilities from Scrivener on David's blog. I commented on David's blog and about an hour later got a tweet from David (a different David) at Scrivener:

"ScrivenerApp: @labrow Noticed your response to @david_hewson (thanks!) post. This video http://bit.ly/byqpvq will probably help your quest. Cheers, DJ."

Rather than repeat the contents of the video, I'm embedding it here for you to watch.

The video is a revelation. I'd expected Scrivener's support for e-book export to be perhaps basic, but far from it – it's a very comprehensive and well-executed export workflow. In fact, I'd say it's so good that even if you wrote using another tool, it would make sense to use Scrivener for e-book creation anyway. Of course, why would you do that when Scrivener is – hands down – the best long-form text creation tool available.

This is incredibly useful for me and, I suspect, for other writers. On a practical level, I now don't have to mess about creating and editing multiple file formats – I just need to export my manuscript from Scrivener in the correct format. My hard disc is awash with different versions of The Well, created either by hand, using an additional tool, or both.

In fact, for someone whose aim really is to (at some point) publish entirely electronically, Scrivener is almost the only tool I need. I say almost, as I still need to output copies for my editor/proofreader, who works on a PC using Word – but I'm looking at ways of getting around that, too.

I can't tell you how much this discovery has made my day. My thanks to the observant David Hewson and my hat is well and truly off to the good people at Scrivener.

(The above just shows how much the Scrivener team care about their customers. Can you imagine the Microsoft Word team getting in touch with a writer after reading something on another writer's blog? No, me neither.)

Filed under: Uncategorized

January 31, 2011

Library lunacy

I'm not the first author to write about this topic and I'm sure I won't be the last. Of the many things the ConDems want to cut (indeed, I'm not sure what will be left intact when they're done) libraries may seem to be a fairly low priority.

After all, what would you rather have – your roads maintained, your bins emptied, great healthcare or a local library? Well, the sad fact is the roads where I live are a potholed mess, the bins are emptied half as frequently as they were and last year I spent ten months being yo-yoed around a health system that still takes six weeks to send the test results from one side of the building to another. Goodness knows where my tax actually goes, but that's another story.

The main problem I have with libraries being axed (or funding reduced) is that it does what many of this Government's cuts do – it marginalises the poor even further.

I have to confess: I don't need or use libraries. I'm lucky enough to be able to buy the books I want and read them on my Kindle. But it wasn't always like that.

I grew up in Bury, Lancashire. This is roughly where my book The Well is set – and where I'm planning on setting future books.

The library was a place that I visited every Saturday morning. From a one-parent family, access to a large supply of books for a child who was a voracious reader was a very good thing.

One of the most exciting days of my young life was the day I was old enough to get an adult library card, which meant not only could I read the grown-up stuff, I wasn't now limited to a book a week. Many was the Saturday when I carried home three or four books.

I was a very well-read child, though I have to confess a preference for science fiction and horror rather than classics. I remember having to add a list of books I'd read, as a bibliography, at the end of an essay – and being challenged by the teacher, who didn't believe I could have read them all.

For me, the library was the only way I could obtain the volume of literature my appetite demanded – and when I fast-forward to today, I have absolutely no doubt whatsoever the role it played in me becoming a copywriter and author.

So, when I hear about cuts to libraries, I picture the thousands – hundreds of thousands – of children for whom free reading will simply not be an option. Imagine the culture to which they will have no access. The opportunities taken away – not just to read, but to become writers, journalists, editors, or simply someone who just loves to read. This isn't just taking away books, it's blocking of culture and it's narrowing career opportunities.

And make no mistake – this isn't just the loss of the odd tiny library. It's a decimation that is going to pull the literacy rug right from under this generation and those to come.

Take a look at how many libraries are affected:

View Larger Map

It's easy for fat, comfortable middle-class people (such as myself) to proclaim that they can get books another way – on the Internet perhaps. I think that's another way of saying 'let them eat cake' and demonstrates really, really clearly how one part of society can simply not understand the needs of another.

And then there's David Cameron's Big Society, one of the smallest ideas I've ever come across. Applied to public libraries, the suggestion is that volunteers man libraries to save costs. What? Do politicians really think that a librarian has no skills and offers no value – and can be replaced by someone with no training? Is this the future? We cut skilled jobs, send intelligent people off to do something menial, then get someone with time on their hands to fill the gap? Dumb.

It's an idea that could only be thought up by somebody who doesn't use – or need to use – a library. Someone who can afford books. And someone who doesn't care about those who can't.

Filed under: Reading

January 28, 2011

Why I prefer Kindle books

Big news for writers and publishers today is that sales of Kindle books have, on Amazon at least, overtaken those of paperbacks for the first time.

According to Amazon: "Amazon.com is now selling more Kindle books than paperback books. Since the beginning of the year, for every 100 paperback books Amazon has sold, the company has sold 115 Kindle books."

This is an astonishing rise to maturity for a market that many thought wouldn't break through because of the 'appeal of paper'.

My publishing goals are – at least currently – very Kindle-centric. I see the e-book as the future, although I am publishing in print (to reach the widest audience and as a marketing exercise, I make very little on the print copies).

Like many people, I love paper too. I love handling books, I love the smell, the touch – it's a tactile experience. But I prefer the Kindle – vastly. With the Kindle, I can read and flip pages with one hand; you can't do that with a book. My library is ready to cart around when I want to travel – all for the weight of less than one book. And the Kindle eco-system is superb: I can loan books to other Kindle users and whatever I'm reading is automatically kept in sync with my other 'Kindle devices' such as my iPhone and iPad. So, if I'm suddenly stuck with 15 minutes to spare and only have my phone with me, I can carry on reading where I left off on my Kindle.

And there's that instant gratification: I can buy it, download it and be reading in less than a minute.

It's not all upside of course. I enjoy browsing in bookshops and was gutted when Borders in the UK bit the dust. I'm sad that many bookshops will eventually go the same way – flicking through books is an enjoyment in itself. (On the upside, I can download 10% of a Kindle book and read it first to decide if I like it.)

The thing with change is that it's unstoppable. E-books are the future – certainly not the entire future (has iTunes destroyed CDs or even vinyl? – nope) but the majority of it.

One of the most gratifying things about the rise of the e-book is that it is encouraging people to read more. Reading is a wonderful, absorbing pastime that could easily get lost in a world where entertainment doesn't usually require much grey matter or a decent attention span. I think, with the rise of the e-book, we're also seeing a renaissance of literary entertainment.

My two big major beefs are price and VAT. I've priced The Well at what I can only say is 'highly competitive' – less than £4. Sadly, many e-books cost as much or more than their printed versions. I was ready to buy Steven Johnson's Where Good Ideas Come From on Kindle and didn't – why? Because it's £12.98 compared to £10.80 in print. I know that's largely the VAT speaking (more of that in a second) but there are no physical costs with an e-book. It should be cheaper.

So: the VAT. Paying VAT on an e-book because it's somehow a service and not a product is stupid and inequitable. It needs sorting out. But I doubt it will be, I've seldom seen governments be willing to relinquish income.

I'd also welcome a common standard across e-book formats, but I can't see that happening – being proprietary hasn't stopped Apple becoming the world number one music reseller. And I don't think it's going to hold Amazon back, either.

Filed under: Publishing

January 26, 2011

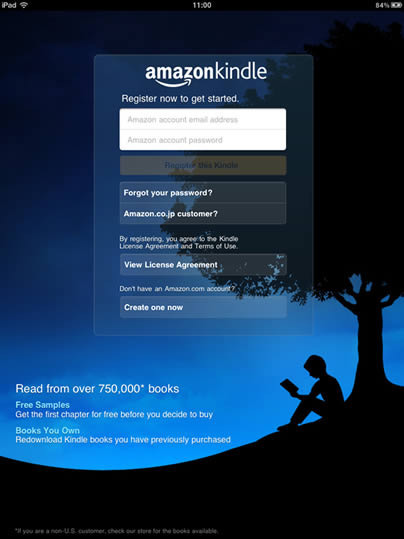

Reading Kindle books on your iPad

Although the iPad has its own reading software, iBooks, the device is also a great platform for buying and reading Kindle books.

The main difference is that the software to read Kindle books isn't installed by default – but adding it is free and easy.

The first step is to download the free Kindle app from the iTunes store. (If iTunes asks you to change which country's store to buy from, then do this.)

You can find the app from within the iPad's App Store by searching on 'Kindle'.

Installation is quick, normally just a few seconds.

The next step is to register your iPad with your Amazon account. If you've not already been prompted when you first launch the app, hit the i button at the bottom right of the screen. Then choose 'register this device'.

All you have to do then is enter the e-mail address and password of your Amazon account, then press 'register this device'.

It's that simple – assuming you have an Amazon account. (If you don't, just log into Amazon's website and create one – if you're in a country where buying Kindle content from that country's website isn't yet supported, you will be redirected to buy Kindle content from the US store.)

You now have access to the full range of Kindle books – all on your iPad.

Despite iBooks having some nice visual touches, I personally believe that the Kindle app provides a superior reading experience. Rather nicely, if you have a Kindle – or any other device with the Kindle app on it, such as an iPhone, PC, Mac or Android phone – then the app keeps the book you're reading synced between all of them, automatically, so you're always on the right page.

Perhaps the first Kindle novel you might want to read after downloading the app could be The Well?

Filed under: Publishing

January 25, 2011

Self-publish and be damned

A dear friend of mine, Emma Clarke, forwarded to me a very interesting article about self-publishing, by Gerald Hornsby.

Like most writers, the goal for myself has always been to 'become published'. Traditionally, this meant the sponsorship of a publisher, or agent and publisher. Sure, the option of self-publishing has long been there, but has been tarnished with the 'vanity publishing' brush – and meant investment up front.

The world is changing. Self-publishing via websites such as CreateSpace and Lulu is relatively simple. Publishing to the Kindle bypasses all of that paper nonsense and sends your work directly into the hands of the reader, without the cost of printing.

It's never been easier to self-publish.

I want to be clear: I didn't opt for self-publishing as an ideological choice. I've nothing against publishers or agents – indeed, I'd be very happy to hook up with either or both, if the partnership was beneficial. I'm very open-minded about it.

I chose to self-publish for several very practical reasons.

I'm an unknown. Publishers are wary of such and have limited resources to promote new authors.

Finding a good publisher is probably harder than writing a novel.

It meant I could get my work out now.

It gave me complete creative control.

I'm also genuinely worried about the publishing industry, which is starting to go through the same massive changes endured by the music industry in the last few years. The channels to market will shift to the Web and reduce in number; physical products will be eclipsed by digital ones; once-powerful publishers will see revenues and profits dwindle. The change is coming – as Gerald Hornsby says, Amazon is predicting sales of 12 million Kindles in 2011; Apple's iPad might outsell the Kindle almost 6 times over.

So, while I'm open-minded about having a publisher, I want to work with one that embraces these changes – and doesn't fumble through, trying to protect the current business model.

The scary point Hornsby makes is that Claire King's next novel will be published by Bloomsbury in 2013. 2013? Two years?

It would be easy to mock and cite this as an example of a sluggish, Jurassic publishing behemoth that needs to get with the times. But as someone who's worked in print, I know that there will be a set of solid reasons for these timescales – it's not in Bloomsbury's interests to hold off launching something from a proven and best-selling author.

But it's something that gives me pause for thought – I would most certainly want my work to hit the streets faster. And I'd want to work with a publisher that wanted the same – not just for commercial gain and self-satisfaction, but also because I want to work with a publisher that's agile enough to not only survive the changes to come to the publishing industry, but smart enough to exploit them.

(And I do think that publishers bring a lot to the equation beyond print and distribution. They have a wealth of writing and market experience.)

Like Hornsby, I have two goals – yes, I want to make money, but I also want people to enjoy my work. This means getting it out there.

Self-publish, or through a publisher, it makes little odds to me – I just want to publish. Right now, I've opted for a route which means I can at least do that. I'm open-minded about the future.

Filed under: Publishing

January 20, 2011

Writing software

I've had a couple of friends ask for advice on writing a book. I usually say that I'm not really the best person to ask, since I'm fairly new to the game. (OK, I've been writing non-fiction for over twenty years, but fiction is very, very different.)

If they press me, I say that I've found three things to be essential:

The support of your partner

A strong network of objective test readers

The best tools for the job

I'll cover the first two briefly, though I may write about them at some point down the line.

Support of your partner

Make no mistake, writing a novel is a massive undertaking. The Well took me a year, from first tap at the keyboard until the Kindle edition was published on Amazon. All the while, I had my day job to attend to – a demanding marketing business. So, I was primarily writing at the weekends and in the evenings – which meant doing a lot less social stuff for a year. Without the support of Ruth, my wife, I couldn't have done it.

A strong network of objective test readers

One thing you miss out on by not having a publisher is the input of an editor. Writing in isolation means that you can get fixated with ideas that could work so much better – if only you'd thought of it. I had around eight people read The Well, several of them more than once. Their input was invaluable – although sometimes brutal – but it really did make a big difference to the finished result. If you can't learn to take criticism, you probably shouldn't be writing – so better to get used to it early on. (In addition, I did pay for an editor/proofreader, who did a fantastic job – including undertaking some research I have to admit I was too lazy to do myself. Kudos, Claire Andrews.)

The best tools for the job

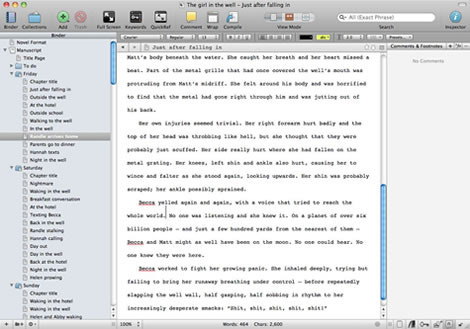

Most people are surprised when I tell them that The Well wasn't written in Microsoft Word. Or Apple's Pages. Or any other 'normal' word processor. It was written in what I think is quite simply the best piece of writing software available, bar none – Scrivener.

I work on a Mac, and as it happens, Scrivener is a Mac-only application (although the publisher of Scrivener, Literature and Latte, is releasing a Windows version in 2011).

For those used to Word, Scrivener can seem initially very alien. Word is very focused on formatting and layout – and, apart from its rather second-rate outlining tool – has very little to help a writer with the structure of his/her work.

But writing a novel requires very little in the way of layout tools – in fact, arguably nothing. Layout is a separate process, it's not part of writing, it's part of publishing. So Scrivener's approach makes perfect sense.

What a writer of fiction needs is a place to store ideas, character notes, location notes, reference text and images, research, build structure, reorganise elements of the piece at will – and help you break down the work into elements that are easy to work with, such as chapters and scenes.

Scrivener does this – and it does it very well. I'm not going to go into massive depth about how it works – better to download the trial version or watch some of the video tutorials on the Literature and Latte website.

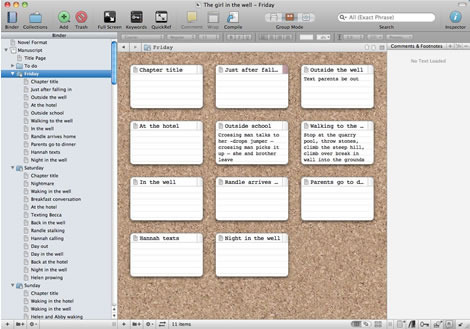

But for me, several aspects of Scrivener were invaluable. First and foremost was the way that Scrivener is non-linear. Your writing consists of components that you can view as a tree, an outline or even a corkboard. And, it's hierarchical, so you can have a corkboard within a corkboard, for example. And you don't have to create this stuff – most of it is automatically created for you as you create documents or folders (here's flexibility: you can turn any document into a folder, too).

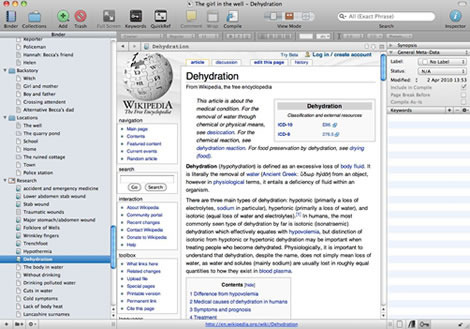

Editing a document in Scrivener - see how chapters and scenes are separate elements

The Well is a series of interwoven plots which follow a very tight timeline – all of the action takes place in less than a week. Scrivener allowed me to easily keep shuffling things around as I needed to, to keep them within the timeline. When I made a major change to the plot, accommodating that change was a piece of cake – you just couldn't have done it within Word without getting totally lost.

Scrivener's corkboards allow you to shuffle your document around really easily

The second thing I couldn't live without is the way that you can store character notes, location notes, references – whatever – all within the same project. No more switching from application to application, or referring to a Rolodex or pinboard on your office wall. And, when you find a key piece of research on the Web, all you need to do is drag and drop it into Scrivener. I remember stumbling across a picture of an antique fighting knife – I dropped it into Scrivener and it later became the reference for the weapon of choice for The Well's supernatural antagonist. No hunting through bookmarks, folders on my hard drive or scrapbooks – the reference was there, where I needed it.

Scrivener can hold all of your research within your writing project

It's impossible to write a blog on everything that Scrivener does – you'd need to write a book. But it is the only piece of long-form writing software that I'd endorse or be enthusiastic about. It's a bit of a learning curve, but only because we're all used to word processors which are essentially layout tools and not writing tools – but once you 'get it' it's entirely logical and very easy to work with.

What's more, it's very inexpensive – and the licence allows you to use it on more than one concurrent machine. Give it a go, you'll be glad you did.

Filed under: Writing, Writing software

January 18, 2011

A borrower or lender be

Ownership's a funny thing. Before I was an author, I didn't think twice about lending or reselling a book. After all, it's mine – I can do with it as I see fit, surely?

It used to be the same with music – how many people of my age have gone through the hassle of getting back the records they lent to their ex-girlfriends? Over the last decade, our attitudes towards ownership have changed. 'Lending' a music track to a friend is now called piracy, or even theft. What's changed? It's my track – why can't I lend it to someone?

Well, the analogy doesn't quite hold up of course. When I 'lend' a music track, I've made a copy to do so; in reality I'm 'giving' it them. And this, I think, is probably one of the biggest flaws with iTunes.

One has to wonder, if you could actually lend music tracks, how much of a dent it would make in piracy? You lend a track to a friend – and while your friend has it, you can't listen to it. When you get it back, you can listen to it again. Your friend gets to find out if they like the track – but it can't be copied ad infinitum. Such technology can't be beyond the wit of Apple. Customers and music companies alike would love it.

That's what Amazon's just done with the Kindle. Kindle owners can now lend a Kindle title – even a title controlled with Digital Rights Management – to another Kindle owner. While their friend has the title, they can't read it – and the lending period is fixed at 10 days, no more. Which is easily enough to either read a book or find out whether you want to buy it.

As a reader and Kindle owner, I would have been delighted with this news. Not being able to lend e-books was the Achilles' heel of the format – the one real and true benefit that real books have over digital ones.

As a writer, I felt somewhat challenged. You only have to look at the price for The Well to realise I don't make much money from it. It's priced low – well, I'm not Stephen King, am I? So, if people are lending my books, does that mean fewer people are buying it? Am I losing sales?

After pondering on it, I decided to relax. If digital books didn't exist, then paper books would still be changing hands – either being lent or sold. It's a system that's worked for hundreds of years – I'll live with it.

In fact, I embrace it – if it gets my name about, on balance, I think it's a benefit. I'd probably go further, too: if Amazon can come up with a way of people selling their e-books on to someone else – and Amazon, the seller and the author get a split of the revenue – then I'm up for it.

It's brilliant thinking and demonstrates Amazon's fundamental understanding of how people want to use its products. Compare that to Apple's dismissive stance – Steve Jobs famously said: "The fact is that people don't read anymore. Forty percent of the people in the U.S. read one book or less last year."

(Yes, the pedant in me would like to point out that it's one book fewer and if perhaps Mr Jobs read more than one book a year, he'd know that.)

Even if that statistic is true and wasn't plucked from the air, book publishing is still an industry worth billions every year. As printed books decline and e-books take over, it's important that the business model is a fair one.

I'd take Amazon's approach to e-books over Apple's approach to music any day. Keep up at the back there, Cupertino.

Filed under: Publishing

January 16, 2011

Cover story

There's a common idiom: "don't judge a book by its cover" – which of course means that you shouldn't take things at face value. But when you're publishing an actual book, the cover is very important – you might not want people to judge the book by its cover, but they will very likely buy it based (at least in part) on the cover.

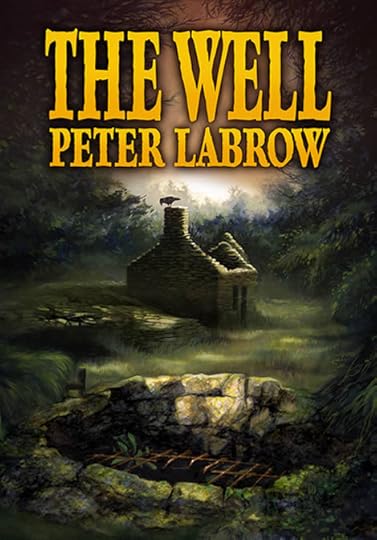

The cover of The Well

For The Well, I started thinking about the cover very early in the writing process. The core of the story is that Becca, a fourteen-year-old girl, is trapped at the bottom of a well. For this to work, I needed the well to be reasonably remote – somewhere people wouldn't look for her.

As chance (and serendipity) would have it, I recalled a photograph taken by one of my closest friends, Martin Mackenzie. It wasn't of a well – it was of a ruined cottage in a wood. It's a great photograph – perhaps not technically perfect, but it's certainly atmospheric. I dug out the photograph and decided that this was definitely the location for the well itself.

The original cottage photograph, taken by Martin Mackenzie

At that time – in the early drafts – the cottage didn't feature at all. It just wasn't part of the story. But once I'd decided that this was the location, I wrote the cottage into the draft – and it became the key location for the climax of the action.

The writing progressed. In The Well, the cottage grew in size – slightly – by necessity from the plot. But once it came to consider the book's cover, I didn't want to change the image of the cottage itself. Not one bit. I decided that strict accuracy wasn't required – the cover had to be a great cover and not slavishly follow my refined descriptions.

Of course, the photograph was lacking one thing: a well.

I'd also decided early on that I preferred to have an illustration for the cover, rather than a photograph. It seems to me that illustrations can convey more than photographs – and I really wanted the cover to seem forbidding and claustrophobic.

The job of creating the (rather wonderful) illustration went to Daryl Joyce, a professional illustrator known for his science fiction work (especially Doctor Who). I'm lucky enough to count Daryl as one of my friends.

Before beginning work, Daryl created a quick photo composite with a well in place. He 'borrowed' the photograph of the well from an illustration and photography website. It was the wrong shape (not quite round) and lacked a protective grating – but in terms of lighting, it was perfect.

I e-mailed Hanna Apaja and secured permission to use the photograph as the basis for the illustration. Well – it's only polite.

Daryl set to work on the illustration and, after a couple of redrafts (Daryl is always really positive about making changes) the cover artwork was born. (I've made it sound as though Daryl's work took minutes, but one look at the illustration shows that he laboured long and hard on this.)

One especially important aspect of the illustration is that I wanted it to be detailed – but it needed to work as a thumbnail on Amazon, which is how most people would initially view it. This balance is something I feel Daryl got exactly right.

Just as the cottage doesn't quite match the description in the book, so there are a few 'continuity' issues with the final illustration versus the text. In the illustration, the well is too close to the cottage, the height of the bricks isn't the same and the surrounding land isn't strewn with old stones from the well wall. None of which is a problem to me – making those changes might make it match the text, but the cover wouldn't be anywhere near as effective as it is. Moving the well away from the cottage, for example, would make the cover feel less claustrophobic.

Nor does the protective grille at the top of the well match the description – but visually, it's better.

Thankfully, when you're self-publishing, the final call is with the writer – and I think the cover is perfect. It may not match the book's descriptions perfectly, but it does reflect the mood of the book and the evil of the location – you might say that, despite the differences, you can tell this book by its cover.

Filed under: Writing

Two face

One of the things people have commented on about The Well is the flawed and often conflicted nature of the characters – thankfully, they've commented in a positive way.

I've always been fascinated by characters who have a degree of duality. As an example, I find Batman far more interesting than Superman. Batman is arguably a violent vigilante with significant Daddy issues. He takes the law into his own hands and often serves up his own justice. And yet, we regard him as the hero. In contrast, Superman is a boy scout who never does wrong. Indeed, he's so nice that he's not only dull, he's characterless.

I've heard it said, quite rightly, that Superman is the one superhero who dons his costume to become himself – where others don them to hide their identities. But I also think he's a rare breed – a long-lasting character without any real flaws (other than a bizarre reaction to Kryptonite).

James Bond is a womanising killer. Tony Soprano is a gangster who needs therapy to get him through. Greg House is the least likeable doctor you'd ever meet. The list goes on.

To me, the conflicted nature of people is what makes them interesting – with the possible exception of the über-baddie, where bad for its own sake can be fair enough.

These are the characters I want to read about – and consequently, these are the characters I want to write. If you read The Well, you'll find that even the protagonists have some fairly significant flaws – and some characters almost sit on the good/bad fence (for example, a policeman who is a loving father but a violent husband).

Hopefully, they're not obviously painted characters with contradictory behaviours, such as Harvey Dent, or Two Face – but are richer, more realistic people as a result. And far more interesting.

Filed under: Writing