Jon Reed's Blog, page 7

October 21, 2018

INTERVIEW: Malorie Blackman

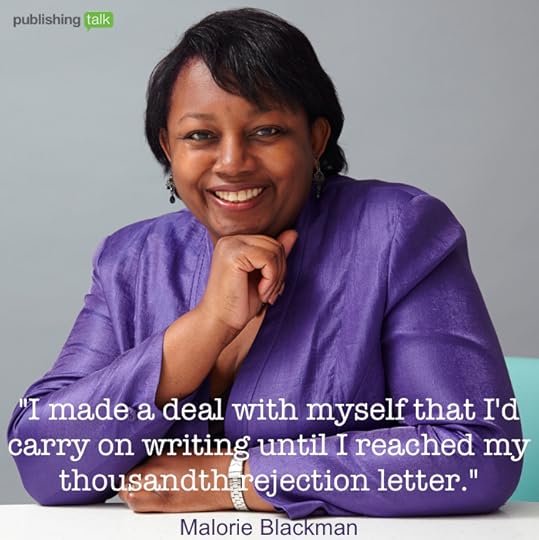

Malorie Blackman, the former Children’s Laureate and champion of children’s literature, talks to Lucy Coats about her path to publication and the obstacles she faced as a writer of colour.

Photo © Random House Children’s Books

This article first appeared in the Children’s Publishing issue of Publishing Talk Magazine (2014). We’re republishing a slightly edited version now to mark Marlorie Blackman’s first Doctor Who episode, co-written with Chris Chibnall, broadcast on 21 October 2018. Malorie also previously wrote a Seventh Doctor short story, ‘The Ripple Effect’, which you can read about in an article called I Have Always Loved Doctor Who on her website. JR

10 minutes to read

Almost everyone has by now heard of Malorie Blackman, OBE – Children’s Laureate, multi-award-winning writer, passionate champion of children’s literature for all ages, and described by The Times as ‘a national treasure’ – but it has been a long and sometimes difficult path to today’s public recognition.

Although she can’t remember a time when she didn’t make up stories and poems, Malorie was eight or nine before she started actually writing them down, in her school English workbooks. A passionate and omnivorous reader, she found it curious that there were no stories by black writers – and certainly none featuring a black girl like her – and it certainly never occurred to her that it was possible for her own stories to get published. Growing up, Malorie says: “There were always too many people ready to set my limits for me.” Told of her lifelong dream to teach, her careers adviser wouldn’t give her a university reference, and suggested she became a secretary instead, as “black people don’t become teachers.” It was only the discovery of Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple in her twenties which planted the seed of the idea that “maybe, just maybe, I too could become a writer.”

I made a deal with myself that I’d carry on writing and sending out my work to publishers until I reached my one thousandth rejection letter.

That process of ‘becoming a writer’ took eighty-two rejections (which represented eight books and two years of her life), but as Malorie herself admits: “I’m very stubborn. I made up my mind that I was going to be a writer and I wasn’t going to give up. I made a deal with myself that I’d carry on writing and sending out my work to publishers until I reached my one thousandth rejection letter. After which I would sit down and have a good long think about whether or not it was ever going to happen.”

As time went on, and the rejections piled up, she was encouraged by the changing tone of the editors’ letters, which became more detailed and longer. “They went from polite but unequivocal ‘not suitable for our list’ to one or two pages explaining why my stories weren’t working. I took it as a positive sign.” Eventually her first collection of short stories – Not So Stupid! was published in 1990 by the now defunct Women’s Press.

It took Malorie three published books before she got her first agent – Michael Thomas at A.M.Heath – but later she changed to Hilary Delamere at The Agency because they also specialised in film and TV contracts, and by then she knew she also wanted to write for TV, which she did very successfully for Byker Grove. “My advice to unagented authors would be to try and get recommendations regarding agents to approach,” she says, and she believes that working with an agent you trust and respect is incredibly important. “You need an agent who is prepared to tell it like it is and give you a verbal kick up the backside,” as well as someone who can “play hardball with publishers without the money aspect souring the relationship between author and editor. A good agent is also a great sounding board for ideas and a safety valve when you want to rant and wail.”

Malorie has worked with many editors over the years – she had eight different publishers in the early days – and she maintains that the editor/author relationship is a kind of negotiation where the editor will see the potential in your ‘vision’, and help you to realize it. However, she is very aware that publishers have other concerns, so sometimes the relationship can also be “about compromise and knowing when to choose your battles.” Her current editor, Annie Eaton at Random House, she describes as “brilliant – a really lovely woman, always tactful and positive, but still able to rein me in when a book seems to be going a little off-the-rails.”

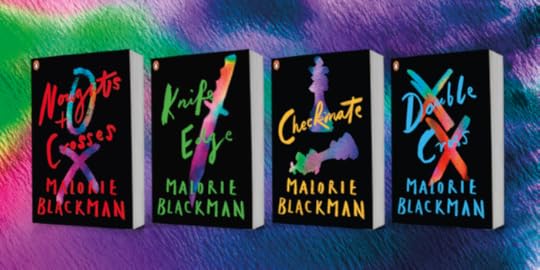

Since the 90s, Malorie has written over sixty books for children of all ages, on a range of subjects from heart-transplants to hacking, but although most of the characters in her books are black it was not until Noughts and Crosses – which turned out to be her breakthrough book – that she chose to address racism. “I have a fear of being labelled – I don’t want to be ‘the X writer’. After 49 books I thought NOW I’m going to write about it – but I’m going to do it MY way. As I writer I have to keep pushing myself, trying new stuff – that’s how you grow.” Of the characters in that book, she says Callum is probably the one she’s closest to. “Things happened to me that happened to him.”

As a writer of colour in her early days of publication, Malorie faced considerable challenges and opposition from some editors, booksellers and librarians, who told her things like ‘no white child will read a book with a black child on the cover’ or ‘white children can’t relate to black issues’ or (even worse in her eyes) ‘the black experience’. She countered by telling them that she was writing about human issues, and to this day says that she still doesn’t know what “the one ‘black experience’ might be”. Such comments were, of course, utter nonsense, and more indicative of the views of the speaker than of any child.

We still need far more diversity in the voices of those published in the UK, and in the publishing industry.

Twenty-four years later things have improved, though Malorie still thinks there’s some way to go. “We still need far more diversity in the voices of those published in the UK, and in the publishing industry.” She’s right. There are almost no British-Chinese or British-Japanese protagonists in UK children’s literature, and very few books about disabled characters which don’t focus on the disability.

While publishers are keen to champion LGBT characters now, even as recently as 2010 when Malorie’s Boys Don’t Cry was published, a gay character like her protagonist Adam was unusual in a children’s book. She quotes Toni Morrison, author of The Bluest Eye: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it” and adds “but get out there and do your research – get your facts straight and get it as good as you can before sending it out.” As for children’s publishing – the fight for more diversity within its ranks is still an ongoing battle.

While publishers are keen to champion LGBT characters now, even as recently as 2010 when Malorie’s Boys Don’t Cry was published, a gay character like her protagonist Adam was unusual in a children’s book. She quotes Toni Morrison, author of The Bluest Eye: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it” and adds “but get out there and do your research – get your facts straight and get it as good as you can before sending it out.” As for children’s publishing – the fight for more diversity within its ranks is still an ongoing battle.

If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it. – Toni Morrison

As with every writer, Malorie’s ‘writing process’ is unique. For her, the gestation of each book is different – some sweep along from original idea to finish with no hiccups, others are a bit like running in a maze, with a lot of doubling back – and there is a whole computer file full of “ideas that not only haven’t blossomed, they haven’t even been planted!” She lists the cycle of emotions each of her books goes through as: “Inspiration, enthusiasm, vague unease, self-doubt, despair, procrastination, insight, renewed vigour, light at the end of the tunnel syndrome, jubilation, exhaustion, disappointed resignation, inspiration, enthusiasm.” However, sometimes an idea is only 90% there. If that happens, “no matter how many ways you twist it round and work on it, you reluctantly have to dump it and move on.”

Malorie is a plotter rather than a pantser, always plans out her books, and spends a great deal of time on her characters’ mini-biographies. “If I feel I’ve really got to grips with them and have created three-dimensional people who are real in my head, they don’t tend to steer me down blind alleys. I trust that if they do deviate from my initial plot idea, it’s for a very good reason.” Those essential mini-bios ensure that she knows exactly how her characters will think, feel and act in any given circumstances.

Malorie says she writes everywhere, and if she’s not on her computer, she’s scribbling in a notebook, but her favourite place to write is her attic. However, she also has an unusual way of solving plot and character problems. “If I’m stuck with a particular chapter or part of my book, I have been known to buy a return ticket, hop on a train and write. Then when I get to my destination, I take the first train home again and write. I’ve done that more than once to solve a writing dilemma and it always works.” There’s an absolute line-in-the-sand must, though – no interruptions. “I find that even little things throw me off my writing stride. I like to sit at my desk and really think and feel my way into my current story.” The distraction of a ringing phone, an email alert, or even an offer of a cuppa can jolt her out of the story and back to reality.

Social media is crucial to anyone writing for children or young adults because it makes the author more accessible.

There is, of course, also the distracting lure of social media – although Malorie maintains that YA fiction writers neglect that side of things at their peril, because “word of mouth and peer review among teens count for a great deal.” She thinks that social media has a role to play both in communicating content to a writer’s audience and advertising the books, and feels that having a social media presence is crucial to anyone writing for children or young adults because it makes the author more accessible.

She does try to limit how much time she spends on Facebook and Twitter, though. “If you’re not careful, they can take over your writing life as the interaction with others can be addictive because the response to whatever you write is immediate. I’d rather spend my day writing stories and poems, not tweeting!” Author visits to schools and libraries are another must – putting in the hard work of connecting with your audience personally, talking about the books, is a way of getting past the gatekeepers and getting your book directly to its intended audience. “If you get children interested in a story,” she says, “they will go for it.”

The 2013-2015 Children’s Laureate was announced as Malorie Blackman at King’s Place in London 04 June 2013. Photo © 2013 Tom Pilston for Booktrust.

The main thing which has taken up most of Malorie’s time in recent years has been the Children’s Laureateship, which makes many demands on her time. She has to factor in interviews (she’s on radio and TV regularly), travelling, appearances in schools, libraries, at festivals and elsewhere – and endless speeches with all the research those entail. She says that being the Children’s Laureate “is a great honour but it’s like having a second full time job.” The right balance is hard to find, and she reckons she’ll probably crack it about a month before she hands over to the next Laureate in June 2015. Inevitably, her writing output has plummeted, and she worries that her publisher and agent “both want to kill me!”

Every book she writes now takes her so long to finish that she has to be absolutely sure that her whole heart and soul are in it before she commits to it. Nevertheless, Malorie feels that the positive far outweigh the negatives, and she has certainly brought her own passions about literacy and reading to the role and made it very much her own, focusing mainly on teenagers and secondary schools. “I have had the chance to meet some amazing people and to try and encourage more children, especially teenagers to read. I’ve already met so many wonderful children and teens as Children’s Laureate. That’s the most rewarding part of what I do.”

Write what you feel passionate about – because publishers don’t always know what the next trend is.

The first UK Young Adult Literature Convention (YALC) took place in July 2014. Curated and directed by Malorie, its huge success with over fifty authors involved is testament to just some of her hard work in that area.

Asked to give advice for new and aspiring writers, Malorie is very definite. Write what you feel passionate about – because publishers don’t always know what the next trend is. “If you have a burning desire to write something then write it,” but she is also adamant that you must do your research and know your market. In practice, this means going to London Book Fair, seeing what’s on the stands, finding out what’s selling and what’s not, asking librarians and booksellers what is popular and why, as well as collecting publishers catalogues.

Once a book is finished, she says, you must “always get on with the next thing.” She herself is still learning new things about her craft. “If I said I wasn’t, that could only mean a) I’m already perfect or b) I’m not interesting in improving. I can assure you neither of those is true!”

Malorie Blackman’s top writing tips

Be true to yourself and your vision when it comes to writing, but don’t be afraid to take advice and to compromise where necessary.

Choose your editorial battles carefully, and remember, you can’t please all the people all the time!

Get out there and do your research. Get your facts straight and make your manuscript as good as you can before sending it out.

Don’t be afraid to move out of your comfort zone more than once in a while. That’s how you stretch and grow as a writer.

Write from the heart as well as the head.

MALORIE BLACKMAN has written over sixty books and is acknowledged as one of today’s most imaginative and convincing writers for young readers. She has been awarded numerous prizes for her work, including the Red House Children’s Book Award and the Fantastic Fiction Award. Malorie has also been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal. In 2005 she was honoured with the Eleanor Farjeon Award in recognition of her contribution to children’s books, and in 2008 she received an OBE for her services to children’s literature. Malorie was the Children’s Laureate 2013–15. To find out more, visit www.malorieblackman.co.uk or follow her on Twitter at @malorieblackman.

MALORIE BLACKMAN has written over sixty books and is acknowledged as one of today’s most imaginative and convincing writers for young readers. She has been awarded numerous prizes for her work, including the Red House Children’s Book Award and the Fantastic Fiction Award. Malorie has also been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal. In 2005 she was honoured with the Eleanor Farjeon Award in recognition of her contribution to children’s books, and in 2008 she received an OBE for her services to children’s literature. Malorie was the Children’s Laureate 2013–15. To find out more, visit www.malorieblackman.co.uk or follow her on Twitter at @malorieblackman.

The post INTERVIEW: Malorie Blackman appeared first on Publishing Talk.

October 18, 2018

8 things to include in your author social media strategy

To develop a successful social media presence, it pays to spend a bit of time developing a strategy first, says Jon Reed.

4 minutes to read

Social media is one of the best ways to connect with readers, build a large, engaged audience – and promote your books. Whether you’re an author working on your own social media, or a publisher developing a social media presence for one of your authors, it pays to think strategically about what you want to achieve.

However, this is still surprisingly rare. Book-based social media is still incredibly prone to last-minute-ism, ‘throw stuff out and see what sticks’, and ‘same old same old’ copycat churn. So make sure you think through these eight elements when putting together a social media strategy, if you really want to see results.

1. Aims and objectives. What do you want to achieve from your use of social media? Don’t just think about book sales: think about building your online platform. That includes follower growth, email signups, raising your profile and positioning yourself as an expert. What are your long-term aims? To write a column? To give a TED Talk? Think big.

2. Measures of success. How will you know when you’ve succeeded? Decide in advance what success looks like for you – and what your ‘key performance indicators’ (KPIs) will be. These are likely to include clickthroughs, follower growth and engagement rate (average number of reactions per post per thousand followers, expressed as a percentage). Be specific. You might, for example, want to double your Instagram followers before your publication date.

3. Social media audit. Where are you now? Unless you’re starting from scratch, you probably have at least some social channels that you’ve been using – albeit perhaps not as frequently or effectively as you would like. Which platforms are you using? How many followers do you have on each? How does this compare with the number of people you follow (your follower ratio)? What type of content are you posting – and how frequently? What is your engagement rate? Consider doing a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats). It can really give an honest picture of what’s going on and why.

4. Audience and competition. Who are you trying to reach? Where can you find them online? Think about the main market you want to reach, and any secondary markets. What platforms do they use, and what sort of accounts do they already follow? Look for similar accounts to your own – and follow their followers. This can be a great way of building your own follower numbers. Think about key influencers too – follow, like and retweet them. It’s not rocket science, but it takes time and grunt work. You can’t just assume ‘build it and they will come.’

5. Social media platforms. Which platforms will you use? Blog, podcast, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Pinterest, LinkedIn? You don’t need to use everything – start small and focus on one or two that you will actually use. Your audience analysis will guide you as to which will be best for reaching your readers – but think too about what you are comfortable with and have time for. Write a one-page strategy for each, including platform demographics, content types you will post, your ‘calls to action’ and measures of success.

6. Content strategy. What types of content will you post? For example: quote cards (images overlaid with quotations, tips or facts from your book); ‘behind the scenes’ posts of the writer’s life; news and announcements; links to relevant blog posts and articles; and any specific promotions that you will run, such as hashtag contests. Put together a spreadsheet, with rows for each platform and columns for content types, frequency, calls to action and measures of success. Yes, it’s an extra layer of work. But if you want to be truly strategic, you need to do it.

7. Editorial timeline. When will you post this content? Some of your content will be ‘evergreen’ and can be posted anytime; some will be tied to critical dates, seasons – or even hashtag trends. You don’t need to plan this in excessive detail, but draw up a spreadsheet with months in the first column – from today until beyond your publication date. Include any important events, such as book festivals, launches or conferences. Then add a column for each platform you’re using, and specify what the focus of your content will be for each month.

8. Email strategy. Yes, this is a social media strategy. But I always include a section on email marketing. You need to build up your follower numbers – but you also need to build your email list. Email tends to be a more effective sales medium than, say, Twitter. Give people an incentive to sign up to your list – such as a sample chapter or free ebook – then promote it on social media. Make sure you collect the necessary consents for email marketing. These are stricter since the introduction of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in May 2018.

I tend to put together a document of up to 20pp, depending on the number of platforms – plus a couple of spreadsheets: a content strategy and a timeline. But you don’t necessarily need a huge amount of documentation in advance, or to launch into using every platform listed in your strategy at once. Your strategy is a living document that will evolve as your needs change over time. But one thing is sure: you do need one. Otherwise you can waste an awful lot of time and energy simply adding to the noise.

This post first appeared on FutureBook on 10 Sep 2018.

The post 8 things to include in your author social media strategy appeared first on Publishing Talk.

October 9, 2018

EVENT: How to Get Published – Saturday 9th February 2019, London

Want to get published? Know someone who does? It’s just four months to our How to Get Published event at Foyles bookshop in London.

How To Get Published

A one-day masterclass for writers

Saturday 9th February 2019 – Foyles, Charing Cross, London

Do you want to get published? Have you written a book but have no idea how to take the next steps? Brought to you by Publishing Talk, the How to Get Published masterclass is an essential day for all authors starting out – whether traditional or indie.

Meet bestselling authors, literary agents, publishers and self-publishing experts as they explain the publishing landscape, the various routes to publication and equip you for career success. Expect no-nonsense, practical advice to motivate you to write that book – and get it published!

Join us at the iconic Foyles bookshop on Charing Cross Road, London for a packed day of great speakers, panels, discussions and plenty of time for networking with fellow writers.

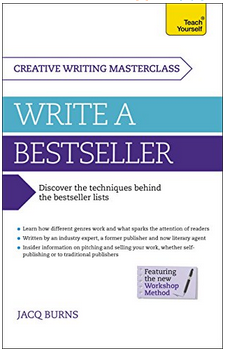

We’re also giving away a FREE copy of Write a Bestseller by literary agent Jacq Burns (one of our speakers) to all delegates – so you’ll have no excuse not to get on and pursue your publishing ambitions!

We’re also giving away a FREE copy of Write a Bestseller by literary agent Jacq Burns (one of our speakers) to all delegates – so you’ll have no excuse not to get on and pursue your publishing ambitions!

What you can expect to learn:

How to get an agent

What publishers are looking for

How traditional publishing works

Alternatives to traditional publishing

How to build your platform online

Full programme and book online

Confirmed speakers include:

Molly Flatt, author of The Charmed Life of Alex Moore

Jacq Burns, literary agent, founder of London Writers’ Club and author of Write a Bestseller

Debbie Young, self-published author and Author Advice Center Manager, The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi)

Anna Lewis, founder of CompletelyNovel

Nick Coveney, Publisher Relations and Content Lead, Rakuten Kobo

Clare Christian, founder of Red Door Publishing

Liz Fenwick, author of One Cornish Summer

Limited earlybird tickets available now.

Hope to see you there!

Book now

The post EVENT: How to Get Published – Saturday 9th February 2019, London appeared first on Publishing Talk.

August 6, 2018

Narrative nonfiction: 7 tips for turning your idea into a book

Narrative nonfiction is nonfiction’s equivalent of the novel, says Daniel Smith. Here’s how to turn your idea into a compelling read.

4 minutes to read

When most people think of writing a book, they usually have a novel in mind. When I was at university, I dreamed of writing fiction too. In fact, I imagined myself hobnobbing with Ian McEwan at some publishing party over a canape and glass of bubbly. But life doesn’t always turn out like you expect. Twenty-odd years later I am, in fact, the author of some thirty works of nonfiction, for both adults and children.

And where my heart really lies is with narrative nonfiction — for me, nonfiction’s equivalent of the novel. It’s where you get to tell a really big, satisfying story over a few hundred pages and hopefully draw in your reader in the same way that good fiction does. When I think of the books that have most affected me, they include narrative non-fiction classics from the likes of Primo Levi and Truman Capote through to more recent masterpieces such as Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. So, if you have that burning desire to write a book, remember that the novel isn’t the only path to take.

And where my heart really lies is with narrative nonfiction — for me, nonfiction’s equivalent of the novel. It’s where you get to tell a really big, satisfying story over a few hundred pages and hopefully draw in your reader in the same way that good fiction does. When I think of the books that have most affected me, they include narrative non-fiction classics from the likes of Primo Levi and Truman Capote through to more recent masterpieces such as Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. So, if you have that burning desire to write a book, remember that the novel isn’t the only path to take.

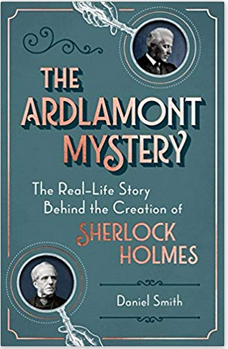

My own most recent book, The Ardlamont Mystery, is narrative nonfiction concerning a true-life Victorian murder mystery. The journey from my first stumbling across the story to the book’s publication was a long one. Over its course, I thought long and hard about the process of writing narrative nonfiction. Here are a few of my thoughts.

Be open. The story you want to tell might stumble into view from anywhere – from a conversation, a magazine article, your own experience. It’s a bit like love; it might take a while to find but when you do, you’ll know it!

Is your story big enough? Sometimes you might think you have the perfect story to tell, but is there enough in it to fill a whole book? This can be a really tough call to make. It might be that you brilliant story is better suited to a magazine feature than to a full-length work, just as in fiction the short story might be your ideal format. If it feels like a story won’t stretch over hundreds of pages, don’t try to force it. It won’t be fun to write or read.

What’s the hook? There are so many amazing stories out there so if you want to write something commercial, it helps enormously to have a hook. Imagine, for instance, that your great-grandfather left the most amazing diaries of his life as a waiter on ocean liners. You might turn them into a fascinating book but why would someone else choose it over any of the other great titles available? Now, imagine if your great-grandfather had been waiting tables on Titanic… there’s your hook. It might not always be something so obvious as that, but try to find something. In my case, the Ardlamont Mystery involved two men upon whom Arthur Conan Doyle based Sherlock Holmes. That was the hook that convinced my publisher.

Has anyone beaten you to it? This may sound rudimentary, but check to see if your idea is so awesome that it’s already been done. Being first to market with a story — or at least, a new take on an old story — gives you far more chance of getting a publisher and finding an audience.

Plot like a novel. Nonfiction by definition relieves the author of some of the effort of inventing a story. Nonetheless, you are still story-telling and need to remember to engage the reader just as you would with fiction. Your characters need to be credible and relatable and your plotting tight. Aim to build suspense and, where possible, show rather than tell. Just because you’re writing nonfiction, it doesn’t need to read like a set of lecture notes. Be in control of the telling but let the story breathe too.

Wear you research lightly. Part of the joy of researching is following all the little threads of a story to see where they lead. Some will turn out to be vital components of your narrative. Others, though, will be merely a distraction. A good writer is also their own editor. Only put in that which drives the narrative forward, even if you end up losing some detail or anecdote that you love.

Speculation is ok but wild guesswork is not. Any story will have its holes. Feel free to fill them with credible theories based on the available evidence (libel and slander aside, of course) but avoid ridiculous leaps of logic even if they make for a juicier story.

The job of the narrative nonfiction writer, then, is really not so different to that of the novelist. It ultimately comes down to finding a story you truly believe in and telling it in the most compelling way you can. As simple as that. As difficult as that.

Daniel Smith’s book The Ardlamont Mystery is out now.

The post Narrative nonfiction: 7 tips for turning your idea into a book appeared first on Publishing Talk.

April 18, 2018

How to write a memoir that matters

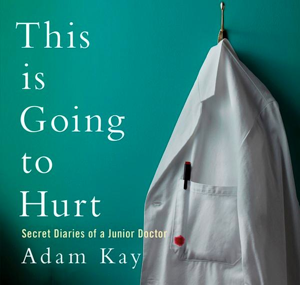

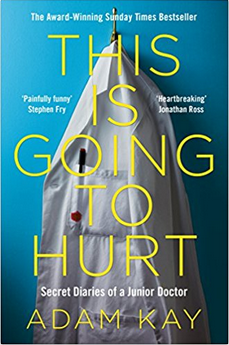

Want to write a memoir? Adam Kay’s hugely entertaining This is Going to Hurt is part of a new trend of immersive memoirs with a message. But what does it take to write and publish one?

11–14 minutes to read

The highlight of this year’s London Book Fair for me was a session called ‘Memoirs that Matter’, with Adam Kay. Adam is the author of the bestselling This is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor – which won the Books Are My Bag readers’ choice award in 2017. The session was chaired by Chris Doyle, senior commissioning editor at his publisher, Picador. The other panellists were: Cathryn Summerhayes, his agent at Curtis Brown; and Rosamund de la Hey, of Scottish independent bookseller The Mainstreet Trading Company, and president of the Bookseller’s Association.

I recently finished listening to the audiobook, and now understand why everyone’s been recommending it to me. It’s laugh-out-loud funny (you might want to avoid listening to it on your daily commute) – but also frequently shocking, occasionally upsetting and has a political message. Adam is now a comedy writer, script editor and performer – and it shows. This is Going to Hurt was a comedy show before it was a book.

I recently finished listening to the audiobook, and now understand why everyone’s been recommending it to me. It’s laugh-out-loud funny (you might want to avoid listening to it on your daily commute) – but also frequently shocking, occasionally upsetting and has a political message. Adam is now a comedy writer, script editor and performer – and it shows. This is Going to Hurt was a comedy show before it was a book.

But before all that, Adam was a doctor. The memoir documents his six years as a junior doctor between 2004 and 2010. Once he no longer needed to keep his medical paperwork, he began clearing it out – but kept his ‘reflective practice’ notes – which form the basis of the book.

There was some discussion at this year’s audiobook-heavy Quantum Conference about when it makes sense for an author to read their own work. Memoir was highlighted as an example of where this can work well, with the right author. Adam is one of those authors. His delivery – even (especially) the footnotes – enhances the experience.

We had a flavour if this during the session, when Adam read a couple of extracts. To avoid spoilers, I shall just call these ‘Kinder Surprise’ (which was received with much hilarity); and ‘Upsetting Patient Diagnosis’ (which wasn’t).

We had a flavour if this during the session, when Adam read a couple of extracts. To avoid spoilers, I shall just call these ‘Kinder Surprise’ (which was received with much hilarity); and ‘Upsetting Patient Diagnosis’ (which wasn’t).

There is considerably more light than shade in the book. Nonetheless, I arrived at the Book Fair the previous day a bit discombobulated, as I’d been listening to it on my way in and had just got to the ‘…and that’s why I’m no longer a doctor’ part. The ‘…that’s why there are no more jokes in this book’ part.

Adam was spotted by a publisher at the Edinburgh Fringe, when This is Going to Hurt was still s a show. Chris Doyle saw it in 2016. He says: “For the first 55 minutes the audience laughed – and then this thing happened at the end, and I’ve never seen such a dramatic reversal.” His colleague Francesca Main had already seen show earlier in year and wanted to turn it into a book. Yet Adam initially left the serious ending out of the show in previews. People enjoyed it, but he had some feedback that it didn’t really have an ending. “It did, but I didn’t want to talk about it,” says Adam. “Six or seven years had elapsed, and I had never really talked about it. The first time my parents knew about why I left medicine was when they read in it hardback.”

It has an ending now. It gets serious, campaigning even – and ends with an open letter to the Health Secretary (who, at the time of writing, is still Jeremy Hunt). The book lures you in with the comedy – then hits you with: ‘right, now I’ve got your attention, THIS is what I actually want to say.’

I wouldn’t have published the book if I didn’t want to affect a bit of change.

– Adam Kay

Adam was initially motivated to write a memoir by the treatment of junior doctors in the UK. They were coming under fire from politicians at the time – being accused of being greedy and in it for the money. Anyone who has read the book cannot possibly believe that characterisation of junior doctors – and that’s the point. Adam may not be able to influence politicians but, by better informing the public, they are less likely to swallow government propaganda. He thought that: “If people knew what [being a junior doctor]meant, hour by hour, no one in their right mind would agree with what they’re being fed by politicians.” He adds: “I wouldn’t have published the book if I didn’t want to affect a bit of change.”

What is a memoir? And what is a ‘memoir that matters’?

These elements – an immersive memoir with a message, which is communicated with a lightness of touch and freedom of form – is part of a growing trend. They are books that are entertaining, emotional and informative, written by someone who’s done something extraordinary and has something to say about it – and they do something to affect change in society. This is a trend that you need to be aware of if you want to write a memoir.

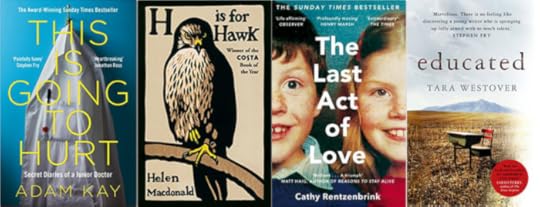

Chris Doyle opened the session by asking each panellist to name a memoir that matters to them. Their choices were:

Rosamund de la Hey: Educated by Tara Westover. It’s a combination of personal story/journey, beautifully written, with enormous heart. In other hands it could have been a misery memoir – in which case I wouldn’t have been interested. It’s the quality of the writing and the context that caught my attention. Tara was brought up in an extreme Mormon family in Idaho – and ended up with doctorate from Cambridge. As bookseller, it’s very easy to get it across to customers. It’s a dream sell, like Adam’s. As an ex-publicist, I think it’s easier to market non-fiction than fiction – because you have more ‘hooks’.

Rosamund de la Hey: Educated by Tara Westover. It’s a combination of personal story/journey, beautifully written, with enormous heart. In other hands it could have been a misery memoir – in which case I wouldn’t have been interested. It’s the quality of the writing and the context that caught my attention. Tara was brought up in an extreme Mormon family in Idaho – and ended up with doctorate from Cambridge. As bookseller, it’s very easy to get it across to customers. It’s a dream sell, like Adam’s. As an ex-publicist, I think it’s easier to market non-fiction than fiction – because you have more ‘hooks’.

It’s easier to market non-fiction than fiction – because you have more ‘hooks’.

– Rosamund de la Hey

Cathryn Summerhayes: My Mad Dad: The Diary of an Unravelling Mind by Robyn Hollingworth. It’s a personal diary by young woman who had the start of very good fashion career in London when she got a call to say father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She decided to move back and become a carer. There are lots of ups – but there’s also the tragedy of realising you’re losing the person who raised you. It matters because our understanding of mental health – depression, degenerative illnesses – is currently in the spotlight. It’s a problem for the NHS and our ageing population.

Cathryn Summerhayes: My Mad Dad: The Diary of an Unravelling Mind by Robyn Hollingworth. It’s a personal diary by young woman who had the start of very good fashion career in London when she got a call to say father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She decided to move back and become a carer. There are lots of ups – but there’s also the tragedy of realising you’re losing the person who raised you. It matters because our understanding of mental health – depression, degenerative illnesses – is currently in the spotlight. It’s a problem for the NHS and our ageing population.

Adam Kay: At the moment I’m reading lot of memoirs that DON’T matter – people keep sending them in – and not everyone has an interesting story. But one I can’t stop thinking about is Cathy Rentznbrink’s The Last Act of Love – an extraordinary story about her brother who’s involved in a traffic accident and is left in a ‘persistent vegetative state’. On the face of it’s a harrowing misery memoir – but it’s told with an extraordinary lightness, and it’s funny. It stuck with me.

Adam Kay: At the moment I’m reading lot of memoirs that DON’T matter – people keep sending them in – and not everyone has an interesting story. But one I can’t stop thinking about is Cathy Rentznbrink’s The Last Act of Love – an extraordinary story about her brother who’s involved in a traffic accident and is left in a ‘persistent vegetative state’. On the face of it’s a harrowing misery memoir – but it’s told with an extraordinary lightness, and it’s funny. It stuck with me.

All of these fit Chris Dolye’s two key criteria that define a memoir:

Fluid in form. A memoir is not the cradle-to-grave account you might expect in an autobiography or biography. It’s more a focused slice of life. A memoir can be fluid in form, about a small area, attached to a particular topic. It moves around more. For example, Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk is about grief – getting over the death of her father by training of a goshawk – but it is also interspersed with a biography of T.H. White.

Written by extraordinary ordinary people. People who write a memoir are not celebrities or famous people. They are extraordinary ordinary people. They’re doing something really amazing but not somebody who already has an audience, such as a world-renowned actor. In the case of The Secret Barrister, even the editor doesn’t know who the writer is. What maters in account of daily life in court.

Cathryn Summerhayes agreed that memoir used to be more autobiographical, but is now more fluid. It has changed. Rosamund de la Hey cited Maggie O’Farrell’s I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes With Death as something with a very fragmentary structure – but the form gives license for that to work.

People writing memoirs are extraordinary ordinary people.

– Chris Doyle, Picador

Extraordinary ordinary people is key to the total immediacy of the genre. We may think we know about being a doctor, a barrister or a carer – but a memoir gives the opportunity for somebody to explain that world to you from the inside.

The real difference, according to Doyle, is that this new genre is about having something to say. It’s all well and good that it gives an insight into world of junior doctor, barrister etc. – but it’s more than just prying in and vicariously seeing what someone else done. It’s taking us into a world but seeking some kind of change – which can be small-scale human-to-human change, or more societal change. Adam Kay’s is a perfect example – complete with a letter to Jeremy Hunt. Two things are key:

Campaigning. A desire to see change in the world. Rosamund de la Hey mentioned Sally Magnusson’s Where Memories Go: Why dementia changes everything , her memoir about caring for her mother. This has a campaigning message and has led to her charity Playlist for Life.

No sugar-coating. In This is Going to Hurt , we get the full blood, sweat and tears – among other bolidy fluids – and see things playing out in real time, such as Adam waking up on Christmas morning having fallen asleep in his car. In My Mad Dad we see Robyn not being able to communicate with her father that mother is dying too.

“It’s really immediate, in your face,” says Summerhayes. “By not sugar-coating it we’re all becoming activists because it motivates us to want to see change.” We’re being asked: Do you realise how bad it is for junior doctors? Do you realise how bad the legal system is?” Doyle agrees: “That openness, opening of the self, emotional honesty, is new.”

Overcoming the resistance to write a memoir

Adam felt comfortable on stage, telling 150 people a night what he thought of Jeremy Hunt – but initially resisted the invitation to write a memoir. He had something to say – but didn’t feel he was able to say it. “I’m not the sort of person who writes a book,” he says. “I’d read lots of books about how to write a book – and they all said you have to read lots and lots of books. I don’t, so I felt unqualified. It took a long time to get over that.”

I’m sure this is an anxiety that many of us have – but Adam’s experience is a lesson in going your own way and telling your own story in the way you want to. It helps that he can write, of course. “These opportunities don’t come along often as an agent,” says Summerhayes. “What sets it apart from many submissions is he’s an incredibly good writer. And I’m sucker for diaries.”

Changing form from stage show to book had it’s challenges. The structure is different in the book to the stage show, as it explains the different roles and levels of seniority – house officer, senior house office, registrar, consultant. There is also an opportunity to explain in more detail than a 70-minute show allows, through the use of footnotes – which are done especialy well. And people want to know the detail. Adam credits his agent with having a huge input in the creative process from first to final draft. “The outtakes were spectacular!” she says.

If you want to write a memoir, you need to get over these anxieties – but it clearly helps having a supportive, creative team around you.

Marketing a memoir

Memoir offers a greater than usual opportunity to involve you as an author – because it is about your own life. You are the ‘product’ as much as your book. Adam spoke at a dinner after the Scottish Booksellers Association conference. This was a slot of only three minutes – but the format suited the book well. “From that moment it became a chain reaction,” says de la Hey. “As a bookseller we’re given hundreds of proofs, and we simply can’t read them all. To get ‘cut through’ is key.”

Adam also did a ton of work to promote the book. It helps that he had a show before the book – and he’s been the length and breadth of country twice over – and treats every event with same respect. As an author, you have to work hard at getting the word out about your book, including using social media. Adam is “flying the flag because he has a cause,” says Summerhayes. “I didn’t want to be the reason the book failed!” says Adam.

That ’cause’ is what should make marketing a ‘memoir that matters’ easier than some other books, though. It’s genuine. “It’s not every author who can hold their book up with pride and say ‘this is my story and this is why I wrote it'” says Summerhayes. It’s why there’s been a diminishing in sales of ghosted memoirs. They just don’t feel authentic – and authenticity is what readers want.

What is the future of memoir?

A couple of questions from the audience touched on the future of memoir.

Q: You said memoirs are becoming more fluid – how do you see them changing more?

Q: You said memoirs are becoming more fluid – how do you see them changing more?

Chris Doyle: From an editorial point of view, it’s the freedom of it – you can almost do anything you like. For example Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk would sound like a mess in most editorial meetings – but it’s extraordinary. The more of these books that succeed in different ways gives us more confidence. The only criteria is: can the writer pull it off?

Cathryn Summerhayes: Beware of the trend to over-share on social media. A lot of these books are 100 pages that have enormous impact. The biggest fear when reading submissions is: are they salacious? Are they overplaying terrible things? It’s the same with literary fiction – you don’t want it to be over-written.

The only criteria is: can the writer pull it off?

– Chris Doyle, Picador

Q. With the rise of #TimesUp and #MeToo, are you expecting to see more survivor stories – such as Helen Walmsley Johnson’s coercive control memoir Look What You made Me Do – and does that bring with it another raft of potential legal issues?

Q. With the rise of #TimesUp and #MeToo, are you expecting to see more survivor stories – such as Helen Walmsley Johnson’s coercive control memoir Look What You made Me Do – and does that bring with it another raft of potential legal issues?

Cathryn Summerhayes: I’m seeing a ton of that in submissions. I have to think about what’s going to work in a crowded market. There might be 30 titles in the window, all of which I want to read; if there’s another 50, will I want to read them too? I’ve been offered a lot of medical memoirs – but have only published two, and one of those was by a vet. I need to know: why are they telling them? Have they enough of a reach to be important to a bigger, more general readership? It has to be something unique. Pubishers are publishing fewer books – and booksellers are selling fewer books.

Rosamund de la Hay: There’s finite shelf space, so the selection process is quite brutal. It’s usually about the quality of writing, combined with the story. It may sound obvious, but it’s true.

Chris Doyle: From a legal point of view, as a publisher you’re not trying to silence anyone’s story – but if it goes wrong you could be on the line for a lot of money; so you have to walk the line between freedom of expression and corporate responsibility.

It’s about the quality of writing, combined with the story.

– Rosamund de la Hay, President of the BA

As with any genre, it doesn’t pay to ‘write to market’. All you can do as a writer is write what you want to write, write it as well as you can – and hope that someone else wants to read it. Authenticity is key, and your unique voice is what people want. But this new trend, this sub-genre of ‘memoirs that matter’, means that we have greater freedom than ever to tell our own stories in our own way. The only requirement is having something to say – and being able to say it well enough.

Six ways to write a memoir that matters

Here are the takeaways I got from the session, which you can apply to your own memoir writing:

Have something to say. You don’t have to be famous to write a memoir. You just have to have something to say.

Choose an angle. Don’t tell us your whole life story from cradle to grave – this isn’t autobiography. Choose an angle, a ‘slice of life’, a topic, an issue.

Get creative. Be playful with form. Adam Kay’s This is Going to Hurt is mostly in the form of a diary. Nina Stibbe’s Love, Nina is in the form of letters home to her sister. Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk is a mashup of overcoming grief through falconry in the present, flashbacks to childhood in the past – and a biography of T.H. White. One of the most unusual memoirs in terms of structure in recent years – but it totally works, is beautifully written – and it won major awards.

Keep it light. The misery memoir boom is over – and is actually off-putting to many agents and publishers now. Don’t hold back – but don’t over-share or over-write either. Get to the emotional honesty of what you want to say – but don’t overplay terrible events to be sensational or salacious for the sake of it. Humour and a lightness of touch are well-received – and this is possible even with the darkest of subjects – such as Cathy Rentzenbrink’s The Last Act of Love .

Be aware of legal issues – but not yet. There’s a hilarious legal disclaimer at the start of Adam’s book – but it obviously required a legal read (then again, who is going to admit to being Kinder Suprise Woman?) However, don’t worry too much about legal issues during the creative writing process. Write what you want to write, then consider any legal issues that it might throw up, and seek advice. (This was discussed at a separate session at the London Book Fair.)

Get out there. As authors, we all have to get involved with the promotion of our books these days. If you’re writing memoir, you surely have an advantage: you have a strong belief in your book (think of the reasons you’re writing a memoir in the first place); and you are the product as much as your book. This can be daunting: you may feel you’re being judged not just on your writing but on your life! But it gives you a unique opportunity to connect with your readers.

This is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay is published in paperback on 19 April 2018.

This is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay is published in paperback on 19 April 2018.

The post How to write a memoir that matters appeared first on Publishing Talk.

How to write a memoir that matters – with Adam Kay

Want to write a memoir? Adam Kay’s hugely entertaining This is Going to Hurt is part of a new trend of immersive memoirs with a message. But what does it take to write and publish one?

11–14 minutes to read

The highlight of this year’s London Book Fair for me was a session called ‘Memoirs that Matter’, with Adam Kay. Adam is the author of the bestselling This is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor – which won the Books Are My Bag readers’ choice award in 2017. The session was chaired by Chris Doyle, senior commissioning editor at his publisher, Picador. The other panellists were: Cathryn Summerhayes, his agent at Curtis Brown; and Rosamund de la Hey, of Scottish independent bookseller The Mainstreet Trading Company, and president of the Bookseller’s Association.

I recently finished listening to the audiobook, and now understand why everyone’s been recommending it to me. It’s laugh-out-loud funny (you might want to avoid listening to it on your daily commute) – but also frequently shocking, occasionally upsetting and has a political message. Adam is now a comedy writer, script editor and performer – and it shows. This is Going to Hurt was a comedy show before it was a book.

I recently finished listening to the audiobook, and now understand why everyone’s been recommending it to me. It’s laugh-out-loud funny (you might want to avoid listening to it on your daily commute) – but also frequently shocking, occasionally upsetting and has a political message. Adam is now a comedy writer, script editor and performer – and it shows. This is Going to Hurt was a comedy show before it was a book.

But before all that, Adam was a doctor. The memoir documents his six years as a junior doctor between 2004 and 2010. Once he no longer needed to keep his medical paperwork, he began clearing it out – but kept his ‘reflective practice’ notes – which form the basis of the book.

There was some discussion at this year’s audiobook-heavy Quantum Conference about when it makes sense for an author to read their own work. Memoir was highlighted as an example of where this can work well, with the right author. Adam is one of those authors. His delivery – even (especially) the footnotes – enhances the experience.

We had a flavour if this during the session, when Adam read a couple of extracts. To avoid spoilers, I shall just call these ‘Kinder Surprise’ (which was received with much hilarity); and ‘Upsetting Patient Diagnosis’ (which wasn’t).

We had a flavour if this during the session, when Adam read a couple of extracts. To avoid spoilers, I shall just call these ‘Kinder Surprise’ (which was received with much hilarity); and ‘Upsetting Patient Diagnosis’ (which wasn’t).

There is considerably more light than shade in the book. Nonetheless, I arrived at the Book Fair the previous day a bit discombobulated, as I’d been listening to it on my way in and had just got to the ‘…and that’s why I’m no longer a doctor’ part. The ‘…that’s why there are no more jokes in this book’ part.

Adam was spotted by a publisher at the Edinburgh Fringe, when This is Going to Hurt was still s a show. Chris Doyle saw it in 2016. He says: “For the first 55 minutes the audience laughed – and then this thing happened at the end, and I’ve never seen such a dramatic reversal.” His colleague Francesca Main had already seen show earlier in year and wanted to turn it into a book. Yet Adam initially left the serious ending out of the show in previews. People enjoyed it, but he had some feedback that it didn’t really have an ending. “It did, but I didn’t want to talk about it,” says Adam. “Six or seven years had elapsed, and I had never really talked about it. The first time my parents knew about why I left medicine was when they read in it hardback.”

It has an ending now. It gets serious, campaigning even – and ends with an open letter to the Health Secretary (who, at the time of writing, is still Jeremy Hunt). The book lures you in with the comedy – then hits you with: ‘right, now I’ve got your attention, THIS is what I actually want to say.’

I wouldn’t have published the book if I didn’t want to affect a bit of change.

– Adam Kay

Adam was initially motivated to write a memoir by the treatment of junior doctors in the UK. They were coming under fire from politicians at the time – being accused of being greedy and in it for the money. Anyone who has read the book cannot possibly believe that characterisation of junior doctors – and that’s the point. Adam may not be able to influence politicians but, by better informing the public, they are less likely to swallow government propaganda. He thought that: “If people knew what [being a junior doctor]meant, hour by hour, no one in their right mind would agree with what they’re being fed by politicians.” He adds: “I wouldn’t have published the book if I didn’t want to affect a bit of change.”

What is a memoir? And what is a ‘memoir that matters’?

These elements – an immersive memoir with a message, which is communicated with a lightness of touch and freedom of form – is part of a growing trend. They are books that are entertaining, emotional and informative, written by someone who’s done something extraordinary and has something to say about it – and they do something to affect change in society. This is a trend that you need to be aware of if you want to write a memoir.

Chris Doyle opened the session by asking each panellist to name a memoir that matters to them. Their choices were:

Rosamund de la Hey: Educated by Tara Westover. It’s a combination of personal story/journey, beautifully written, with enormous heart. In other hands it could have been a misery memoir – in which case I wouldn’t have been interested. It’s the quality of the writing and the context that caught my attention. Tara was brought up in an extreme Mormon family in Idaho – and ended up with doctorate from Cambridge. As bookseller, it’s very easy to get it across to customers. It’s a dream sell, like Adam’s. As an ex-publicist, I think it’s easier to market non-fiction than fiction – because you have more ‘hooks’.

Rosamund de la Hey: Educated by Tara Westover. It’s a combination of personal story/journey, beautifully written, with enormous heart. In other hands it could have been a misery memoir – in which case I wouldn’t have been interested. It’s the quality of the writing and the context that caught my attention. Tara was brought up in an extreme Mormon family in Idaho – and ended up with doctorate from Cambridge. As bookseller, it’s very easy to get it across to customers. It’s a dream sell, like Adam’s. As an ex-publicist, I think it’s easier to market non-fiction than fiction – because you have more ‘hooks’.

It’s easier to market non-fiction than fiction – because you have more ‘hooks’.

– Rosamund de la Hey

Cathryn Summerhayes: My Mad Dad: The Diary of an Unravelling Mind by Robyn Hollingworth. It’s a personal diary by young woman who had the start of very good fashion career in London when she got a call to say father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She decided to move back and become a carer. There are lots of ups – but there’s also the tragedy of realising you’re losing the person who raised you. It matters because our understanding of mental health – depression, degenerative illnesses – is currently in the spotlight. It’s a problem for the NHS and our ageing population.

Cathryn Summerhayes: My Mad Dad: The Diary of an Unravelling Mind by Robyn Hollingworth. It’s a personal diary by young woman who had the start of very good fashion career in London when she got a call to say father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She decided to move back and become a carer. There are lots of ups – but there’s also the tragedy of realising you’re losing the person who raised you. It matters because our understanding of mental health – depression, degenerative illnesses – is currently in the spotlight. It’s a problem for the NHS and our ageing population.

Adam Kay: At the moment I’m reading lot of memoirs that DON’T matter – people keep sending them in – and not everyone has an interesting story. But one I can’t stop thinking about is Cathy Rentznbrink’s The Last Act of Love – an extraordinary story about her brother who’s involved in a traffic accident and is left in a ‘persistent vegetative state’. On the face of it’s a harrowing misery memoir – but it’s told with an extraordinary lightness, and it’s funny. It stuck with me.

Adam Kay: At the moment I’m reading lot of memoirs that DON’T matter – people keep sending them in – and not everyone has an interesting story. But one I can’t stop thinking about is Cathy Rentznbrink’s The Last Act of Love – an extraordinary story about her brother who’s involved in a traffic accident and is left in a ‘persistent vegetative state’. On the face of it’s a harrowing misery memoir – but it’s told with an extraordinary lightness, and it’s funny. It stuck with me.

All of these fit Chris Dolye’s two key criteria that define a memoir:

Fluid in form. A memoir is not the cradle-to-grave account you might expect in an autobiography or biography. It’s more a focused slice of life. A memoir can be fluid in form, about a small area, attached to a particular topic. It moves around more. For example, Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk is about grief – getting over the death of her father by training of a goshawk – but it is also interspersed with a biography of T.H. White.

Written by extraordinary ordinary people. People who write a memoir are not celebrities or famous people. They are extraordinary ordinary people. They’re doing something really amazing but not somebody who already has an audience, such as a world-renowned actor. In the case of The Secret Barrister, even the editor doesn’t know who the writer is. What maters in account of daily life in court.

Cathryn Summerhayes agreed that memoir used to be more autobiographical, but is now more fluid. It has changed. Rosamund de la Hey cited Maggie O’Farrell’s I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes With Death as something with a very fragmentary structure – but the form gives license for that to work.

People writing memoirs are extraordinary ordinary people.

– Chris Doyle, Picador

Extraordinary ordinary people is key to the total immediacy of the genre. We may think we know about being a doctor, a barrister or a carer – but a memoir gives the opportunity for somebody to explain that world to you from the inside.

The real difference, according to Doyle, is that this new genre is about having something to say. It’s all well and good that it gives an insight into world of junior doctor, barrister etc. – but it’s more than just prying in and vicariously seeing what someone else done. It’s taking us into a world but seeking some kind of change – which can be small-scale human-to-human change, or more societal change. Adam Kay’s is a perfect example – complete with a letter to Jeremy Hunt. Two things are key:

Campaigning. A desire to see change in the world. Rosamund de la Hey mentioned Sally Magnusson’s Where Memories Go: Why dementia changes everything , her memoir about caring for her mother. This has a campaigning message and has led to her charity Playlist for Life.

No sugar-coating. In This is Going to Hurt , we get the full blood, sweat and tears – among other bolidy fluids – and see things playing out in real time, such as Adam waking up on Christmas morning having fallen asleep in his car. In My Mad Dad we see Robyn not being able to communicate with her father that mother is dying too.

“It’s really immediate, in your face,” says Summerhayes. “By not sugar-coating it we’re all becoming activists because it motivates us to want to see change.” We’re being asked: Do you realise how bad it is for junior doctors? Do you realise how bad the legal system is?” Doyle agrees: “That openness, opening of the self, emotional honesty, is new.”

Overcoming the resistance to write a memoir

Adam felt comfortable on stage, telling 150 people a night what he thought of Jeremy Hunt – but initially resisted the invitation to write a memoir. He had something to say – but didn’t feel he was able to say it. “I’m not the sort of person who writes a book,” he says. “I’d read lots of books about how to write a book – and they all said you have to read lots and lots of books. I don’t, so I felt unqualified. It took a long time to get over that.”

I’m sure this is an anxiety that many of us have – but Adam’s experience is a lesson in going your own way and telling your own story in the way you want to. It helps that he can write, of course. “These opportunities don’t come along often as an agent,” says Summerhayes. “What sets it apart from many submissions is he’s an incredibly good writer. And I’m sucker for diaries.”

Changing form from stage show to book had it’s challenges. The structure is different in the book to the stage show, as it explains the different roles and levels of seniority – house officer, senior house office, registrar, consultant. There is also an opportunity to explain in more detail than a 70-minute show allows, through the use of footnotes – which are done especialy well. And people want to know the detail. Adam credits his agent with having a huge input in the creative process from first to final draft. “The outtakes were spectacular!” she says.

If you want to write a memoir, you need to get over these anxieties – but it clearly helps having a supportive, creative team around you.

Marketing a memoir

Memoir offers a greater than usual opportunity to involve you as an author – because it is about your own life. You are the ‘product’ as much as your book. Adam spoke at a dinner after the Scottish Booksellers Association conference. This was a slot of only three minutes – but the format suited the book well. “From that moment it became a chain reaction,” says de la Hey. “As a bookseller we’re given hundreds of proofs, and we simply can’t read them all. To get ‘cut through’ is key.”

Adam also did a ton of work to promote the book. It helps that he had a show before the book – and he’s been the length and breadth of country twice over – and treats every event with same respect. As an author, you have to work hard at getting the word out about your book, including using social media. Adam is “flying the flag because he has a cause,” says Summerhayes. “I didn’t want to be the reason the book failed!” says Adam.

That ’cause’ is what should make marketing a ‘memoir that matters’ easier than some other books, though. It’s genuine. “It’s not every author who can hold their book up with pride and say ‘this is my story and this is why I wrote it'” says Summerhayes. It’s why there’s been a diminishing in sales of ghosted memoirs. They just don’t feel authentic – and authenticity is what readers want.

What is the future of memoir?

A couple of questions from the audience touched on the future of memoir.

Q: You said memoirs are becoming more fluid – how do you see them changing more?

Q: You said memoirs are becoming more fluid – how do you see them changing more?

Chris Doyle: From an editorial point of view, it’s the freedom of it – you can almost do anything you like. For example Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk would sound like a mess in most editorial meetings – but it’s extraordinary. The more of these books that succeed in different ways gives us more confidence. The only criteria is: can the writer pull it off?

Cathryn Summerhayes: Beware of the trend to over-share on social media. A lot of these books are 100 pages that have enormous impact. The biggest fear when reading submissions is: are they salacious? Are they overplaying terrible things? It’s the same with literary fiction – you don’t want it to be over-written.

The only criteria is: can the writer pull it off?

– Chris Doyle, Picador

Q. With the rise of #TimesUp and #MeToo, are you expecting to see more survivor stories – such as Helen Walmsley Johnson’s coercive control memoir Look What You made Me Do – and does that bring with it another raft of potential legal issues?

Q. With the rise of #TimesUp and #MeToo, are you expecting to see more survivor stories – such as Helen Walmsley Johnson’s coercive control memoir Look What You made Me Do – and does that bring with it another raft of potential legal issues?

Cathryn Summerhayes: I’m seeing a ton of that in submissions. I have to think about what’s going to work in a crowded market. There might be 30 titles in the window, all of which I want to read; if there’s another 50, will I want to read them too? I’ve been offered a lot of medical memoirs – but have only published two, and one of those was by a vet. I need to know: why are they telling them? Have they enough of a reach to be important to a bigger, more general readership? It has to be something unique. Pubishers are publishing fewer books – and booksellers are selling fewer books.

Rosamund de la Hay: There’s finite shelf space, so the selection process is quite brutal. It’s usually about the quality of writing, combined with the story. It may sound obvious, but it’s true.

Chris Doyle: From a legal point of view, as a publisher you’re not trying to silence anyone’s story – but if it goes wrong you could be on the line for a lot of money; so you have to walk the line between freedom of expression and corporate responsibility.

It’s about the quality of writing, combined with the story.

– Rosamund de la Hay, President of the BA

As with any genre, it doesn’t pay to ‘write to market’. All you can do as a writer is write what you want to write, write it as well as you can – and hope that someone else wants to read it. Authenticity is key, and your unique voice is what people want. But this new trend, this sub-genre of ‘memoirs that matter’, means that we have greater freedom than ever to tell our own stories in our own way. The only requirement is having something to say – and being able to say it well enough.

Six ways to write a memoir that matters

Here are the takeaways I got from the session, which you can apply to your own memoir writing:

Have something to say. You don’t have to be famous to write a memoir. You just have to have something to say.

Choose an angle. Don’t tell us your whole life story from cradle to grave – this isn’t autobiography. Choose an angle, a ‘slice of life’, a topic, an issue.

Get creative. Be playful with form. Adam Kay’s This is Going to Hurt is mostly in the form of a diary. Nina Stibbe’s Love, Nina is in the form of letters home to her sister. Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk is a mashup of overcoming grief through falconry in the present, flashbacks to childhood in the past – and a biography of T.H. White. One of the most unusual memoirs in terms of structure in recent years – but it totally works, is beautifully written – and it won major awards.

Keep it light. The misery memoir boom is over – and is actually off-putting to many agents and publishers now. Don’t hold back – but don’t over-share or over-write either. Get to the emotional honesty of what you want to say – but don’t overplay terrible events to be sensational or salacious for the sake of it. Humour and a lightness of touch are well-received – and this is possible even with the darkest of subjects – such as Cathy Rentzenbrink’s The Last Act of Love .

Be aware of legal issues – but not yet. There’s a hilarious legal disclaimer at the start of Adam’s book – but it obviously required a legal read (then again, who is going to admit to being Kinder Suprise Woman?) However, don’t worry too much about legal issues during the creative writing process. Write what you want to write, then consider any legal issues that it might throw up, and seek advice. (This was discussed at a separate session at the London Book Fair.)

Get out there. As authors, we all have to get involved with the promotion of our books these days. If you’re writing memoir, you surely have an advantage: you have a strong belief in your book (think of the reasons you’re writing a memoir in the first place); and you are the product as much as your book. This can be daunting: you may feel you’re being judged not just on your writing but on your life! But it gives you a unique opportunity to connect with your readers.

This is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay is published in paperback on 19 April 2018.

This is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay is published in paperback on 19 April 2018.

The post How to write a memoir that matters – with Adam Kay appeared first on Publishing Talk.

March 26, 2018

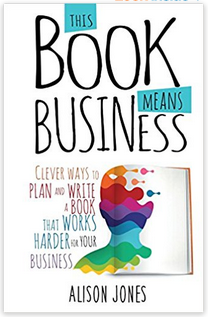

Why your book is your greatest marketing tool

The book used to be the thing you marketed. Today it’s also a tool to market yourself or your business. Business coach, content consultant and publisher Alison Jones shares her advice for using self-publishing as a business strategy.

This article appeared in issue 7 of Publishing Talk Magazine, and first appeared on this blog on 17 Oct 2017. Alison Jones’s new book This Book Means Business publishes today.

5 minutes to read

I work with businesses and organisations with something to say. So this article is primarily about non-fiction, books that showcase expertise or aim to educate or inform. But whatever you’re writing, a book represents a significant investment of your time, and it’s worth being clear about what return you want from that investment.

A battle for attention

A book used to be pretty much the only vehicle by which authors could reach readers. It lost that USP the day the Web was invented. Over the last couple of decades multiple sub-species of author-friendly communication have evolved: ebook, web page, video, microvideo, elearning, infographic, animation, app, game, webinar, podcast, post, pin, tweet. And unlike the traditional book, which is self-contained and self-sufficient, these new kids on the block exist in a complex matrix of referral and response.

As an author, what you’re actually engaging in is a battle for attention. You could see all these other forms of communication as competing with your book, or you could see your book as an integral part of this rich, dynamic ecosystem of content – part of your content marketing strategy. (Hint: I’m going to be selling the latter.)

It’s a mind flip. The book used to be the thing you marketed. Today it’s ALSO the tool by which you market yourself or, in the case of most of my clients, your business or organisation. If content is the ultimate proof of concept, the book remains the ultimate form of content.

Is it still worth writing a book?

In this busy new communication landscape, is it still worth writing a book? After all, it’s a significant drain on your time and energy, when as a business owner there are so many other demands on both. The opportunity cost is high: how can you be sure this indeed the best possible use of your time? How can you be sure that people will still buy into the idea of the book at all in a year’s time, let alone five years from now?

Oddly enough, I believe it’s the very fact that the book is so familiar, well-established and embedded in our culture that makes it a safe bet, for now at least. I’d argue that investing your time in mastering a new social media channel is more risky, as it’s more likely to be rendered irrelevant by the next innovation. (Which is not to say you shouldn’t – it’s vital that you keep up with new channels as they emerge, not as a slave to the latest fad but as part of a thoughtful content marketing strategy.) In a world in which platforms are emerging and evolving at a dizzying rate, the shared cultural understanding of what a book is and how it works is priceless. When people are facing disruption and novelty at every turn, a book represents the familiar, the secure, the trusted.

Books are part of our psyche. We look to them for information and inspiration.

Books are part of our psyche. We look to them for information and inspiration. We trust and respect those who write them. And we should: the act of writing a book, a good book, at least, is an exercise in crystallizing and refining thought, in distilling experience and intelligence. A blog post captures and develops a thought: a book sustains and processes that thought into something more, something fuller and deeper.

In a book, you have space and time to set out a compelling narrative rather than a superficial tagline. For any potential customer genuinely interested in what you can offer, this is an unparalleled opportunity to get to know you and what you stand for.

Be a generous author

Several would-be authors have worried out loud to me about ‘giving away’ their secrets in their book. There’s an old marketing adage that used to be received wisdom – ‘Give ’em the sizzle, not the sausage’ – meaning that you should always keep something back, give them a reason to cough up more money, tease them with suggestions of something more. I encourage authors to take a more generous-spirited view: to stretch a metaphor to its breaking point, there will always be more sausages, and once they have the sausage, they will come back for the egg and bacon and fried bread. And if they don’t, at the very least you will have had the satisfaction of satisfying others and doing yourself justice in the process.

Guy Kawasaki has a different food-related metaphor. For him, there are two kinds of people in the world: bakers and eaters. ‘Eaters think the world is a zero-sum game: what you eat, someone else cannot eat, so they eat as much as they can. Bakers think that the world is not a zero-sum game—they can just bake more and bigger pies. Everyone can eat more. People trust bakers and not eaters.’ Be a baker: everyone loves bakers, and there are far too many eaters in the world already.

If you don’t write this book, eventually someone else will.

And if that doesn’t convince you, consider this: if you don’t write this book, eventually someone else will. Is it better for your potential clients to associate all that wonderful, rich information with you, or with your competitor?

Beyond the book

It doesn’t stop with the published book, of course. It doesn’t even start there. While you’re planning and writing your book, consider how you can engage your ‘tribe’ with the book you’re creating: ask questions, invite contributions, put titles or covers up for public vote, share extracts, blog about the experience of writing. If someone makes a particularly valuable contribution, credit them in your acknowledgements. One of my authors crowdfunded her book and has a ready-made sales team waiting for launch to tell the world about the book that bears their name.

Having codified your methodology in your book, can you translate it into an Udemy course or a 1-day workshop?

Once the book’s finished, start thinking what’s next: having codified your methodology in your book, can you translate it into an Udemy course or a 1-day workshop?

That whole panoply of communication channels and social media is at your disposal. Be creative, and be clear about what you’re saying, who you’re saying it to, and why.

There’s never been a better time to write a book. Think strategically and focus on the benefits you want that book to secure for you – whether that’s generating leads, establishing credibility, increased visibility, speaking gigs, whatever it is you know that you want it to achieve for you and/or your business. In addition you’ll achieve something you might not have expected: the satisfaction of creating something unique and worthwhile, of speaking in your authentic voice about the things that you care passionately about. This frequently turns out to be one of the great, enduring achievements of your life.

Alison Jones’s new book This Book Means Business publishes today.

Alison Jones’s new book This Book Means Business publishes today.

The post Why your book is your greatest marketing tool appeared first on Publishing Talk.

December 14, 2017

What does a literary agent do?

Children’s agent Hilary Delamere answers a frequently-asked and fundamental question about agents: What are they for and what do they do?

5 minutes to read

This article first appeared in issue 6 of Publishing Talk Magazine – also available as a Kindle edition.

Agenting is best thought of as a partnership with the client: working together to get published, to build an author’s or illustrator’s profile and career.