Marcus Speh's Blog, page 4

January 20, 2013

The Rat King

The man stopped reading. The girl looked at him: “Did you honestly think, daddy that this story would scare me? Don’t you know how old I am? Do you know anything about me? I read the last Harry Potter book when I was seven,” she said. “Well,” said her father, “truth be told your mother read it to you. And she gave the old Rowling a sanitizing makeover so that you wouldn’t be traumatized for the rest of your life.” He smiled one of those smiles that he had smiled for the first thirteen years of her life, but lately, as now, his smile had only embarrassed his daughter, as if he was pretending an intimacy that she had begun to shed like dry snakeskin.

The man stopped reading. The girl looked at him: “Did you honestly think, daddy that this story would scare me? Don’t you know how old I am? Do you know anything about me? I read the last Harry Potter book when I was seven,” she said. “Well,” said her father, “truth be told your mother read it to you. And she gave the old Rowling a sanitizing makeover so that you wouldn’t be traumatized for the rest of your life.” He smiled one of those smiles that he had smiled for the first thirteen years of her life, but lately, as now, his smile had only embarrassed his daughter, as if he was pretending an intimacy that she had begun to shed like dry snakeskin.

On a balcony outside of the small apartment, The Lord of Demon Flies stood listening and glistening in the rain. All along the street the rats had emerged from the sewers. Paws raised, they looked up at their Lord as large, cold drops fell on them and soaked the hairs that had been so carefully braided in preparation for Halloween and the Great Demon Flight. What was their master doing up there with the humans? Why wasn’t he preaching to them?

The father left the room and closed the door behind him. He took his story with. Perhaps it was time to stop reading to the child. Perhaps it was time to stop thinking of her as a child. As he stood in the corridor, he had a sudden bad feeling like a draft from some unclosed window of the soul. He stopped and wondered if he should go back and check up on the girl, but he hesitated: he’d been too cautious since his wife had died. It was clear that his daughter needed space above all. He scuffled to his desk, back to his work and put on headphones to listen to music. The house fell still.

The girl opened her laptop. Behind her, Beelzebub changed into a fat, iridescent green horsefly, buzzed around her head and landed on top of the web cam. The girl had joined a hangout. A dozen teenagers from around the world were logged in and chatting all at the same time. The girl was jiggling around like Beyonce, so that Beelzebub in his insect self felt competitive with the human and joined her in mid air for a little dance. The girl tolerated the buzzing body for a bit, but when she felt too bothered she grabbed the fly with a quick left hand and squished it, so that the Prince of Darkness had difficulty escaping and, as there was no time to find another small body, he entered the computer.

The girl opened her laptop. Behind her, Beelzebub changed into a fat, iridescent green horsefly, buzzed around her head and landed on top of the web cam. The girl had joined a hangout. A dozen teenagers from around the world were logged in and chatting all at the same time. The girl was jiggling around like Beyonce, so that Beelzebub in his insect self felt competitive with the human and joined her in mid air for a little dance. The girl tolerated the buzzing body for a bit, but when she felt too bothered she grabbed the fly with a quick left hand and squished it, so that the Prince of Darkness had difficulty escaping and, as there was no time to find another small body, he entered the computer.

But the electrical impulses hit him with unexpected force and his spirit was drawn further into the machine. Like a drowning man he was pulled out to the open sea. Deep currents of communication, stronger than anything he had experienced throughout millennia, held him there. Millions of man-made tiny silvery switches and golden gateways were processing him like freshly caught fish in a can factory. Only fractions of a second later – he himself didn’t know how it had happened – the Dark One was spread out over the entire net. His great evil was distributed too thinly now across the planet to do any harm to anyone for a long time except through flame wars, hate mail and small furious comments on Facebook.

Down on the street, as the clock was eating away at Halloween, the rat mob gave up on their king and the rodents slowly disappeared into the night.

From: “A Rat Story“, collaborative “Halloween Garage Sale” motivated and coordinated by Jules Archer (posted Oct 27, 2012). This was my part—the complete story including the parts written by Jules Archer, Meg Tuite, Julie Innis and Susan Tepper is here. Enjoy!

January 11, 2013

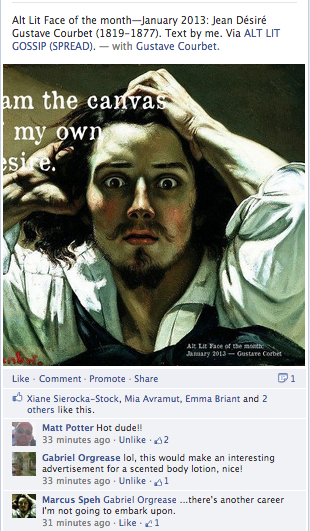

A Facebook Feuilleton

I’ve given you a lot of heads and citations this last month on Facebook. It’s been a month dominated by Victorian writers (most notably: Henry James), Victorian novels and illustrations, and some literary criticism (Joseph Epstein, Ford Madox Ford). I hope you enjoy the kaleidoscope of my predilections most of which manifested themselves in the course of my novel research which forces me to write through time and space like a mad scientist. Like three months ago when I last did this, each post is accompanied by a minor meditation of transient significance. Click on any picture for a detailed view.

I’ve given you a lot of heads and citations this last month on Facebook. It’s been a month dominated by Victorian writers (most notably: Henry James), Victorian novels and illustrations, and some literary criticism (Joseph Epstein, Ford Madox Ford). I hope you enjoy the kaleidoscope of my predilections most of which manifested themselves in the course of my novel research which forces me to write through time and space like a mad scientist. Like three months ago when I last did this, each post is accompanied by a minor meditation of transient significance. Click on any picture for a detailed view.

From all that I have read it seems to me that H.G. Wells, who wrote a book specifically to make fun of the style of Henry James, was but jealous of the older man’s skill. Wells, of course, was as different as one could possibly be: an economic upstart, highly successful with the public, a writing scientist and sometime politician (with the Fabians), steeped in sexuality and affairs, battling Victorian prudery. Altogether a personage and writer to be admired just like James but for different reasons. David Lodge has written highly readable fictional biographies about both James (“Author! Author!”) and Wells (“A Man Of Parts”), with the loving lashing tongue of the satirist.

From all that I have read it seems to me that H.G. Wells, who wrote a book specifically to make fun of the style of Henry James, was but jealous of the older man’s skill. Wells, of course, was as different as one could possibly be: an economic upstart, highly successful with the public, a writing scientist and sometime politician (with the Fabians), steeped in sexuality and affairs, battling Victorian prudery. Altogether a personage and writer to be admired just like James but for different reasons. David Lodge has written highly readable fictional biographies about both James (“Author! Author!”) and Wells (“A Man Of Parts”), with the loving lashing tongue of the satirist.

Queen Victoria stands for so many contradictions that I don’t even know where to begin: prudery vs. the outside and prostitution on the inside (the fallen madonna); the sentimental, regressed desire to withdraw to a cottage in the hills (immortalized by a later age as Middle-Earth’s “Shire”)

Queen Victoria stands for so many contradictions that I don’t even know where to begin: prudery vs. the outside and prostitution on the inside (the fallen madonna); the sentimental, regressed desire to withdraw to a cottage in the hills (immortalized by a later age as Middle-Earth’s “Shire”)  vs. the horror unleashed by the Empire in the colonies; the foundation of modern realistic writing vs. the mistrust against uncovering the power of libido in the unconscious (a task that fell to Freud)…obviously still a time that looms large in British fantasies. Undoubtedly there would be a similar reverie for Imperial Germany before the two world wars if we hadn’t started those wars…

vs. the horror unleashed by the Empire in the colonies; the foundation of modern realistic writing vs. the mistrust against uncovering the power of libido in the unconscious (a task that fell to Freud)…obviously still a time that looms large in British fantasies. Undoubtedly there would be a similar reverie for Imperial Germany before the two world wars if we hadn’t started those wars…

This post caused quite a discussion at Fictionaut focusing on the relationship between the reader and the writer, or the reader is (real and imagined) and the writers (real and imagined). It probably needs to be revisited again and again by every writer throughout the lifetime. I have this belief that just as we take some of the source material for our writing from the field of humanity surrounding us, the collective unconscious if you will, we also return something to it when we make art, independent of anyone consciously registering or reading the result of our art-making. A simpler way to put it would be that art always changes the world even if only you are changed by it. If I write a story this changes me even if nobody sees it and in effect my behavior changes…and the world has moved on a little. Some may call this extremely tiny and meaningless but we are not talking about ego here but rather, I suppose, soul or field of influence and meaning.

This post caused quite a discussion at Fictionaut focusing on the relationship between the reader and the writer, or the reader is (real and imagined) and the writers (real and imagined). It probably needs to be revisited again and again by every writer throughout the lifetime. I have this belief that just as we take some of the source material for our writing from the field of humanity surrounding us, the collective unconscious if you will, we also return something to it when we make art, independent of anyone consciously registering or reading the result of our art-making. A simpler way to put it would be that art always changes the world even if only you are changed by it. If I write a story this changes me even if nobody sees it and in effect my behavior changes…and the world has moved on a little. Some may call this extremely tiny and meaningless but we are not talking about ego here but rather, I suppose, soul or field of influence and meaning.

Always, always torn, as a participant of these brave new worlds of social media, between skipping and salvaging. One of the better excuses that I have for my own ambivalence is that there has never been an audience of over 1 billion for anyone or anything. The force field created by these millions dominates the day. At times, I find it hard to tear myself away, and other times real-life thankfully intervenes, and once in a while (as happened this last week) I’m grateful for the ongoing global dialogue. Special thanks to some of you, who engage at a high level of discourse, who offer more than tiring daily trivia. Nothing against trivia, of course: we all thrive on them, we sit on them like on a plush pillow of nought. There would be no peaks without the troughs.

At times, I find it hard to tear myself away, and other times real-life thankfully intervenes, and once in a while (as happened this last week) I’m grateful for the ongoing global dialogue. Special thanks to some of you, who engage at a high level of discourse, who offer more than tiring daily trivia. Nothing against trivia, of course: we all thrive on them, we sit on them like on a plush pillow of nought. There would be no peaks without the troughs.

I meant for this to be the year of reading Proust and perhaps that will still happen, but instead it’s turning into the year of reading Henry James. Right from the very start (of his novel-writing) I’d say if James himself had not successfully tampered with his own beginnings: in his last decade he reworked many of his novels and stories and turned out the so-called New York edition of his works. These include his famous prefaces for the edited versions (which amount to an entire course on the Art of Fiction on their own). — I was surprised to find out that many publishers simply publish the version of James’ work that they prefer rather than what must be considered the definite edition. This affects books from James’ early period like “Roderick Hudson” and “The American”. The publishers are not forthcoming with a lot of information: sometimes, there is a “Note on the text” that states the fact and justifies it by claiming that the earlier version sounds more “fresh”. In one case (Penguin), samples from both editions are printed next to one another…but there’s nothing obvious about preferring the early James. Electronic editions (including those of Project Gutenberg and Kindle—though to be fair practically the only way to get hold of some of the later James is via electronic archive) completely suppress the existence of the later version. Worse of all, often the preface which was written for the new version and the old “fresh” version are printed together (of course, without an explanation). This practice smacks of butchering and I’m surprised nobody seems to care (conspiracy!?). For “Roderick Hudson“, I have compared both the earlier (1875) and the later (1907) version: the later James is always more accurate, less cliched and more complex. But this isn’t Dan Brown: this is Henry James, the master of consciousness, the literary Freud of the English language, the grand master of the artistic self, twin of Marcel Proust—…

I meant for this to be the year of reading Proust and perhaps that will still happen, but instead it’s turning into the year of reading Henry James. Right from the very start (of his novel-writing) I’d say if James himself had not successfully tampered with his own beginnings: in his last decade he reworked many of his novels and stories and turned out the so-called New York edition of his works. These include his famous prefaces for the edited versions (which amount to an entire course on the Art of Fiction on their own). — I was surprised to find out that many publishers simply publish the version of James’ work that they prefer rather than what must be considered the definite edition. This affects books from James’ early period like “Roderick Hudson” and “The American”. The publishers are not forthcoming with a lot of information: sometimes, there is a “Note on the text” that states the fact and justifies it by claiming that the earlier version sounds more “fresh”. In one case (Penguin), samples from both editions are printed next to one another…but there’s nothing obvious about preferring the early James. Electronic editions (including those of Project Gutenberg and Kindle—though to be fair practically the only way to get hold of some of the later James is via electronic archive) completely suppress the existence of the later version. Worse of all, often the preface which was written for the new version and the old “fresh” version are printed together (of course, without an explanation). This practice smacks of butchering and I’m surprised nobody seems to care (conspiracy!?). For “Roderick Hudson“, I have compared both the earlier (1875) and the later (1907) version: the later James is always more accurate, less cliched and more complex. But this isn’t Dan Brown: this is Henry James, the master of consciousness, the literary Freud of the English language, the grand master of the artistic self, twin of Marcel Proust—…

…fittingly, here’s the most confrontational quote of the month. It came to me via Joseph Epstein and incorporates a quote from Cynthia Ozick on the state of literature:

…fittingly, here’s the most confrontational quote of the month. It came to me via Joseph Epstein and incorporates a quote from Cynthia Ozick on the state of literature:

«“Modernism as a credo seems faded and old-fashioned, if not obsolete,” Ms. Ozick writes, “and what we once called the avant-garde is now either fakery or comedy. The Village where Auden and Marianne Moore once lived and wrote and walked abroad is a sort of performance arena nowadays, where the memory of a memory grows fainter and fainter, and where even nostalgia has forgotten what it is supposed to be nostalgic about. Distinction-making, even distinction on as I stated the winners will show up as a sole monies that here is about what you are what you to come from over the vocabulary from what you are okay if Idiscerning, is largely in decline. The difference between the high and low is valued by few and blurred by most.” In short, in literature the game of high art, high culture, highbrowism generally, the tradition of Henry James and Joseph Conrad, Virginia Woolf and T. S. Eliot, is over.

To be replaced by what? Perhaps a great messy mélange of low- and middlebrow writing, admixed with highbrow pretensions, with graphic novels taken as seriously as written ones, screen and television writers being celebrated as if they were of the stature of Thomas Mann or Albert Camus. And yet one wonders how long this lowering of standards, this infantilization of literature, can continue….Might it be that the time for “workshopping” is over and the time to get to work has at long last begun?»

From: Joseph Epstein, “the literary life” at 25, in: New Criterion, 09/2007

Poor Ford Madox Ford (geb. Hueffer). A contemporary of such modernizer-giants of literature Henry James and Joseph Conrad (both a generation older than he), he scrambled and fretted and agonized over his own place in the pantheon. Alas, his headstone is much smaller, a bronze where James gets gold and Conrad silver. However, he fabricated worthwhile accounts of his appreciation for both elders. I enjoyed his essay on James and his biographical novel on Conrad with whom he also collaborated on several (supposedly forgettable, but I have not read them) novels.

Poor Ford Madox Ford (geb. Hueffer). A contemporary of such modernizer-giants of literature Henry James and Joseph Conrad (both a generation older than he), he scrambled and fretted and agonized over his own place in the pantheon. Alas, his headstone is much smaller, a bronze where James gets gold and Conrad silver. However, he fabricated worthwhile accounts of his appreciation for both elders. I enjoyed his essay on James and his biographical novel on Conrad with whom he also collaborated on several (supposedly forgettable, but I have not read them) novels.

A few months ago, I wrote a German text about being angry with myself after buying books by Thomas Bernhard. I will translate it and post it here at some point. He doesn’t really belong in the same section as all the other heads except that he wears a Trilby.

A few months ago, I wrote a German text about being angry with myself after buying books by Thomas Bernhard. I will translate it and post it here at some point. He doesn’t really belong in the same section as all the other heads except that he wears a Trilby.

Not a head but makes me think of one! In 1979, the year of Einstein centenary celebrations, as a 15 year old, I visited the Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt in Neuchatel. Though I didn’t know him and though I had not even announced myself (I just rang at his door), he treated me to lunch, listened to my youthful views, took a tape on which I had spoken (!) a few of my stories and (I presume) stories, fed me his favorite dessert (a bit of sorbet swimming in a lake of Vodka) and sent me on my way wholly convinced that being a writer was the best thing any man could be or do or want to be. It took me 30 years to get back to that point but it was a worthwhile journey.

Not a head but makes me think of one! In 1979, the year of Einstein centenary celebrations, as a 15 year old, I visited the Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt in Neuchatel. Though I didn’t know him and though I had not even announced myself (I just rang at his door), he treated me to lunch, listened to my youthful views, took a tape on which I had spoken (!) a few of my stories and (I presume) stories, fed me his favorite dessert (a bit of sorbet swimming in a lake of Vodka) and sent me on my way wholly convinced that being a writer was the best thing any man could be or do or want to be. It took me 30 years to get back to that point but it was a worthwhile journey.

Have begun to watch old Bergman movies again. They’re painful. Woody Allen makes Bergman’s style look fun, but he’s more serious (and more existentially obscure) than Woody could ever be. I do this partly because of a new interest in the 1970s and partly, I suppose, because of the way Bergman lets his personas do what they want so that some of the difficulties of just being and living your life, which he, as an oftentimes depressed person, must have felt very acutely, perhaps more acutely than I, but certainly more publicly, because the characters that I have written about so far have not experienced too much moral or intellectual or physical hardship: it feels as if by focusing on the absurd side of life which of course exists and is most attractive to the roaming mind, the real self, the real person, is denied some of its weight. This is a shortcoming that I would like to remedy in my new novel. And Bergman, maybe the whole Swedish aesthetic, could well be one of the guiding lights to reach a new place.

Have begun to watch old Bergman movies again. They’re painful. Woody Allen makes Bergman’s style look fun, but he’s more serious (and more existentially obscure) than Woody could ever be. I do this partly because of a new interest in the 1970s and partly, I suppose, because of the way Bergman lets his personas do what they want so that some of the difficulties of just being and living your life, which he, as an oftentimes depressed person, must have felt very acutely, perhaps more acutely than I, but certainly more publicly, because the characters that I have written about so far have not experienced too much moral or intellectual or physical hardship: it feels as if by focusing on the absurd side of life which of course exists and is most attractive to the roaming mind, the real self, the real person, is denied some of its weight. This is a shortcoming that I would like to remedy in my new novel. And Bergman, maybe the whole Swedish aesthetic, could well be one of the guiding lights to reach a new place.

Tolstoy’s “What is Art?” (in the 1995 Pevear/Volokhonsky translation, however) is on my desk these days (Many things are, including dirty handkerchiefs, a Chinese fortune cookie that says ‘It’s not what you know but who you know’, and a Swedish 1 Kr coin). He writes about the modern (in 1895) tendency of replacing art by “a simulacrum of art”—something not quite real, a diversion, an imitation of the real thing. Now, back to my purely intellectual hole-digging…

Tolstoy’s “What is Art?” (in the 1995 Pevear/Volokhonsky translation, however) is on my desk these days (Many things are, including dirty handkerchiefs, a Chinese fortune cookie that says ‘It’s not what you know but who you know’, and a Swedish 1 Kr coin). He writes about the modern (in 1895) tendency of replacing art by “a simulacrum of art”—something not quite real, a diversion, an imitation of the real thing. Now, back to my purely intellectual hole-digging…

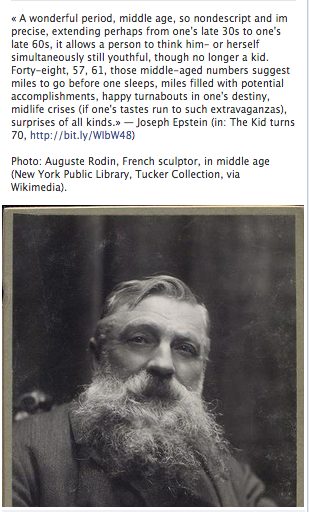

Let me close with more male hair (picture: Auguste Rodin) and another Epstein quote:

Let me close with more male hair (picture: Auguste Rodin) and another Epstein quote:

«A wonderful period, middle age, so nondescript and im precise, extending perhaps from one’s late 30s to one’s late 60s, it allows a person to think him- or herself simultaneously still youthful, though no longer a kid. Forty-eight, 57, 61, those middle-aged numbers suggest miles to go before one sleeps, miles filled with potential accomplishments, happy turnabouts in one’s destiny, midlife crises (if one’s tastes run to such extravaganzas), surprises of all kinds.»

— Joseph Epstein (in: The Kid turns 70. And nobody cares.)

So much for January so far so good so fancy 19th century. And I wrote three poems, too, but ssshh don’t tell because as you know I don’t write poems.

January 6, 2013

How do you manage your inner critic?

“Here is a piece of a troll herb which nobody else but me can find” (Source: Wikimedia)

Before I disappear once more in my teaching trapdoor, I would like to table a big question about the writer’s inner process. In particular the process of writing in the first stages when the germ of a new story must be tended to with utmost care and caution lest it should die an early death.

One of the characteristics of this stage is the confrontation with the “Inner Critic” (for lack of a better term—better term anyone?) who asks all manner of grown-up, sharp, civilized questions and who evidently looks at the beloved germ with the eyes of a gardener rather than a Creator. Clearly, both inner critic and inner creator are needed to complete the work. As Dorothy Brande (“Becoming a Writer”, 1934) pointed out, it’s deadly to have them both in the room at the same time. However, for the practicing writer, they are of course both present at all times.

[image error]

“Blitzkrieg”: the danger of sudden collapse.

While I have encountered this issue with my shorter fiction, it didn’t bother me much then: with all short forms, the Creator can move in and can grow the whole thing comparatively quickly; or, if you prefer military metaphors: the short form knows the successes of “Blitzkrieg”. Of course, that’s not the whole story, but in my experience it is easier with short pieces to lay a strong foundation so that when the inner critic arrives on the scene, he can hardly do too much damage. At least this is my early analysis of the problem.

For longer forms of writing, the long ‘short story’ even, or the novella or (worst of all) the novel, I do not have current have an analysis or recipe; my method currently is to do all my plotting and structuring in English but switch to German when I do my trance work, the actual writing. Somehow, crossing the language barrier disables the inner critic rather effectively.

Gollum! Gollum!

Hence my question: how do you manage your inner critic during the first stages of writing (say: during first draft)? Do you deflect the critic? Do you integrate the critic? And how exactly do you do it?

A always, all stories count, all experiences lead to Rome! All artists must jump through similar hoops—perhaps you have a creative idea even if you’re not a writer?

PS. I do not want to withhold the voice of a grand master —though this quote from one of Henry James’ letters concerns external criticism, it also reveals the shape and structure of his INNER stronghold:

PS. I do not want to withhold the voice of a grand master —though this quote from one of Henry James’ letters concerns external criticism, it also reveals the shape and structure of his INNER stronghold:

«…I know tool perfectly well what I intend, desire and attempt, and am capable of following it absolute absence of perturbation. Never was a genius — if genius there is — more healthy, objective and (I honestly believe) less susceptible of superficial irritations and reactionary impulses. I know what I want — it stares one in the face, as big and round and bright as the full moon; I can’t be diverted or deflected by the sense of judgments that are most of the time no judgments at all.» —Henry James (1878)

James’ central proposition I believe is “I know what I want”. This points at a solid position of thematic, philosophical certainty which over the period of many years of craftsmanship turned into imperviousness against the destructive impulses of critics. I think successfully dealing with the inner critic always comes first and will help you deal with the Outer Critics, too.

[Cross posted at Fictionaut][See also: How to start a novel]

December 31, 2012

The last letter

[Click here to listen to the story]

«Whenever I begin to think about editing and publishing my father’s angry, political poems, I am overwhelmed by the multitude of images that surround my recollection of his gray head bent over the typewriter, looking up like a blind man who scans the inside of an unseen world, or perhaps of a lost world, charging ahead into the unknown like Professor Challenger, never surprised at what he finds and always willing to generously spread the treasure around among those willing to listen. He gets up, waves a piece of paper, says “pearls before swine” to no one in particular, grabs his well thumbed copy of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, scratches himself, which makes an odd noise because he’s wearing his tight leather pants never mind that he is in his 70s, and flops on the couch. Pulling the book over his eyes he begins to snore. Later, he will wake up, remember the rhythm in which the wings of his nose flapped during his nap, and then he will spend hours trying to transfer this rhythm to his writing, crouched at the feet of one of the great libraries of the city like a book, like a bat turned into a book, like the last letter of a secret alphabet that must memorize itself, and so it goes on and on in my head until a friend rescues me from my memory banks and takes me out for a beer in Berlin.»

This flash piece was motivated by my reading a novelized biographical account of the last days of H G Wells in “A Man Of Parts” by David Lodge. After plowing through the book (or most of it—haven’t manage to finish it yet), I took my iPad pencil to a photograph printed in Wells’ “Experiment in Autobiography” (1934) and created the picture you see here. It has become my permanent computer desktop background. The two different eyes in the picture keep me entangled in my own dream as I’m dictating away…

December 9, 2012

How to start a novel

Dostoevsky’s notes for chapter 5 of “The Brothers Karamazov”

“The world is very big.”

Writer and musician Stephen Hastings-King (SHK) said this in a recent discussion on Fictionaut titled “starting a novel” that was begun by Tyler Findlay (TF). I made some observations that I wish to recycle here. I’ve done this before. Before my antics begin to tire you, by all means go to the forum to see the entire discussion.

MS: I am also very interested in the question of “how to start a novel” though after writing a couple of these beasts, I am less confident that there are any ready-made answers. Still you are asking about experiences, and I’ve got some:

TF: How do you begin a piece?

MS: if by “piece” you mean “flash fiction” then the answer is that it mostly comes to me pretty much in one piece like a poem might come to the poet or an image to the painter. If by “piece” you mean “novel”, my answer would be: very, very slowly, returning to the same crossroads many, many times, so many times in fact that I often feel these days as if I’m chasing my own fictional tail. For me, a novel isn’t just a slice of life —that’s how I look at flash — but it’s life itself, which is why every single confusion, dead end and wrong start that you experience every day is mirrored in the process of composing the novel. However, call it unfortunate or call it fortunate, there is no shortcut to the serious novel I believe. I’ve made a few attempts in the direction of genre writing and it feels different: much more like walking down a road better known in a group of characters more familiar than in the case of the serious novel.

Erectile outlines: Former German general Halder at the Nuremberg trials 1945.

TF: Do you erect extensive outlines?

MS: I didn’t used to do this and the result was that I would create interesting characters galore and wonderful, arresting scenes and begin to dream of possible paths and plots and endings, but I would never finish. After months of bliss for writing I’d end up with a bundle of golden tangents but not with a story, not with a novel. Hence now I linger a lot longer before beginning the writing process in earnest. Though I may write individual scenes if they come to me. But the writing proper begins only after I have created an extensive outline. This way of working is still somewhat new to me. It feels a lot less creative at times and a lot craftier but it keeps the whole together. I don’t know any other way to do this unless you don’t care about narratives. If you write junk or experimental novels obviously all of this does not apply to you…

TF: …Or does it flow freely?

MS: in between writing the outline and editing first draft it does flow freely, it must or else why do it?

TF: What am I failing to wrap my mind around to get from point A to point B?

MS: the purpose of the outline that I’m talking about is to indicate or say, rather, as specific as possible, how your characters get from A to B. That’s the whole point. There’s nothing more to it and nothing less, alas. I can’t say that it’s easy for my creative temper to follow this path. However, having written many hundreds of flash stories I feel that I have exercised the devil of short ends and can now begin to wrestle with the devil of the long road.

Pick a POV. Play with it. Serious writers grow a moustache and win awards.

Which POV?

MS: I agree with David [Ackley]‘s statements, too. Though Henry James’s third person, I believe, is mostly omniscient, while Kafka’s, e.g. is close 3rd, i.e. the narrator follows the main protagonist. Close 3rd has the advantage that it can be turned into a first-person POV without effort. Personally, I write in yet another 3rd person POV right now: you can find it in the first half of Dostoyevsky’s “The Idiot” and many of his other novels as well as in Flaubert: it’s a POV where the reader only ever stays with the protagonist but does not know what the protagonist thinks or feels. Instead, everything that happens has to be shown and must not be told. Dostoyevsky make this work by using dialogue like nobody else: you can get lost in his dialogue, it’s a trance transporter… anyway, I’m not finished with the POV problem myself. Sometimes I think it doesn’t matter greatly because these days you can change POV and the readers will forgive you. However, your story may not.

Enter SHK from left. SHK wears goggles. He looks at you suspiciously with the green, penetrating eyes of the “formalist” (his term for himself). He responds, ending with the line: ”Everything is political.”

Some popes were hilarious, too

MS: It’s interesting that you Stephen (Hastings-King: “Everything is political.”) put your statements into 2nd person while I (“Wrestling with devils”) pour forth in the 1st person.

At the same time, we’re both academic scholars. But my heart isn’t in it to be frank. One reason for this is that I abhor pontification (must be because I am Catholic), another that I have come to think that this business of writing is so exquisitely so exclusively and extremely subjective that you may just as well call it dreaming. That this business of writing is also a business with an audience makes the whole affair perfectly paradoxical.

You see (going into 2nd person here as I have begun to pontificate myself…), writing novels for me is giving an expression to the collective unconscious as well as my personal unconscious. There are all kinds of things in the unconscious, of course, revolution (SHK: “It’s a good time to blow up this novel business”) being one of them. But also myth-making, a form of weaving that must go on for thousands of years or else it is fast food and evaporates (SHK: “And what is writing beyond making figures?”).

“I lived in that story, I inhabited it like a shell.”

To me the telling of long stories is something that I feel in my bones and under my skin not just for philosophical reasons but because my dad told me a long, long story when I was a boy, every night, for years on end. I lived in that story, I inhabited it like a shell. It’s my beginning, or one of them, this is where I started and this is where I’m still going when things are rough and when I’m lost (Like this: “Paralysis, deterioration, a slow pathetic fade into a self-imposed shadow world.”—SHK).

Wanting to preserve the novel is silly, just as silly as wanting to preserve the moon. Wanting to write novels as a continous dream building on rock-solid narratives, easy concepts for any one human to wrap themselves in, is not silly. It’s the most serious game that can be played. Creation through causation to bring light to the poor shadows that are real for you, for me.

Everything is spiritual.

[image error]

Gaston Bachelard: “The words of the world want to make sentences.”

Later, I thought that I could have said “everything is personal”. Fortunately, Fictionaut’s forum engine does not allow editing and revising after submitting an entry. Also, somehow, I felt bad for sort of equating “academic writing” with “pontification”, so I added:

MS: the best academic writing isn’t pontification of course, it’s not any less exciting and rebellious and respectful of the spirit as the best novels. Some examples: Sebald (“On The Natural History of Destruction“), Girard (“Deceit, Desire & The Novel“), Bachelard (“The Poetics of Reverie“), everything written by Sigmund Freud, etc etc

SHK (at the end of a longer reply):

“[...] I still want to blow things up. I still am driven by a sense of the political. But mostly, I like to walk around. The world is very big.”

I don’t think the case for the novel can really be made more succinctly. It made me want to take a walk (which is also when I’m dictating my best work):

MS: [...] And I’ve also begun to walk around. I used to want to construct the world now it feels as if I’m being constructed by the world.

Some people always have to have the last word.

Walking around in the snow. Why not do it now?

…The debate continues at Fictionaut now including some expert POV playing and use of footnotes as well as footnotes to footnotes by Matthew J Robinson.

October 30, 2012

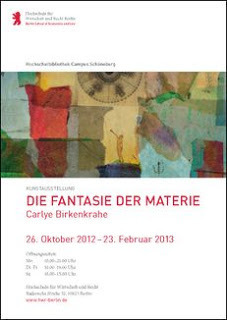

The Imagination of Matter

Part of “Parisiennes 3 (triptych)” by Carlye Birkenkrahe

All art is competition: to begin with there is the artist competing with her art’s own inner image. She imagined one thing and created another. Now the latter must be transformed into the former. She cannot win this battle against the infinitely, quick footed, invisible enemy: her own imagination. Still, this sweet contest is the original source of the human desire to create beauty.

As soon as the finished piece of art confronts the viewers there is more rivalry in the air. The viewers can’t help imagining themselves. Perhaps their imaginings came out of their fantasies about the artist, and out of their views of her abilities or the power of the medium. Or perhaps these viewers have already seen a reproduction of the painting and wrestle with their own memory.

This reminds me of the Louvre, of battling with the tourist mob and its clicking cameras until we finally stand before the Mona Lisa, the worlds most discussed painting. At first we can see anything because our imagination has been fed so many impressions that the small, rather inconspicuous painting can hardly keep up. But just like every other painting it possesses the invaluable advantage of physical reality. This is why any dab of paint will always touch us more strongly than the fleeting word. And now I will return from the lofty to the ground.

[image error]

“God at his creation” by Carlye Birkenkrahe

A few days ago I attended the opening of my wife’s art exhibition at a location which properly showed the contest between word vs. picture, between written vs. painted truth. The place of the exhibition was a library. From the viewpoint of the books that lived there already, it was an invasion. The books were used to competing amongst themselves, of course. As the toys in the nursery books buy into strict hierarchy: there are the oldest books whose position was undisputed and there were many others that still had to find their proper place. Age, relevance, binding, beauty and many other things to count when books determine their relative importance. There were the most recently published books enjoying the boost of youth but also carrying the curse of cursoriness which is the legacy of modernity. They all had a home in this library and suddenly a platoon of paintings pushed into that space.

To begin with, the books didn’t follow. Several among them, the illustrated books at least, had already encountered these alien beings made of color and lines and whatnot. The illustrated books eagerly pointed out that they stood between the purebreds and the new arrivals. The non-illustrated books wrinkled their spines at this suggestion. We don’t need no pictures, they said. Everything we are comes out of the word itself. But their illustrated cousins were not listening any longer: they had begun to chat with the new pics on the block.

The time of the vernissage was approaching but it wasn’t here yet. The paintings had already been hung and were beginning to exchange small jealousies. A small picture complained that it was hung too close to the edge. A large one asked for more white space around itself. And another one, convinced it was the best ever created by the artist, ceased chatting because it wished to gather strength for the decisive moment: the confrontation with the viewer. What kind of gallery is this anyway? asked some of the more recent paintings. They had been exhibited neither in private nor in public. They were squinting, trying to get used to the new lighting conditions. A more mature tableau declared that this was a library. But do we even belong here? asked one of them. The majority of the paintings thought they did. They felt the time was ripe. To the books on the shelves they suggested there should be peace between books and pictures. There was some muttering and scrambling until the elders on both sides reminded their fellow artifacts that all of them were serving humanity. Well put, said one of the paintings. It was one of the artist’s earliest creations and had never been seen by anyone but the artist: it had waited for this moment to come.

Eingangsbereich der Bibliothek der HWR Berlin Campus Schöneberg

By the way, neither books nor pictures in this space were ancient at all. The books weren’t novels, poetry or manuscripts. It was a technical library, which means that the spirit of science was alive here and what the books might have lacked in passion they made up for by their ability to make logical decisions and bow to rational considerations. At the same time they noticed how different the paintings were from them, not just with regards to material but also meaning.

[image error]

“Chimeaerazons” by Carlye Birkenkrahe (private collection)

The paintings were not scientific illustrations, nor were they icons, but they were filled with symbols from both, they were pieces of art that wanted to be deciphered (because symbols are created by the viewer in the viewing, and thus the picture is never as passive as we think). The resistance to decoding and being decoded was not an intellectual one, but an emotional one, due to the inevitable struggle between the viewer and the picture. It generated a different form of heat, if you like. Indeed, for reasons not easily explained by today’s science, the cohabitation of books and paintings led to a slightly raised room temperature. To us, however, who know everything, it is clear that the difference in temperature corresponded to the energy tied up in the contest between books and paintings.

Before either side could get lost in this dialogue, the first visitors arrived at the opening. Many of them had never been to this particular library, which flustered the books and agitated them not a little. The truth is that being looked at by a human and finally being picked from among others on its shelf is the highest honor for any book. It’s the book’s fulsome praise. (At least until the reading proper begins. This is like the difference between falling in love and learning to love one another.) Hence, although still feeling competitive, the books were not dissatisfied. I won’t even try to convey the excitement of the paintings. Several of them lost consciousness during the short speech of the president of the school where the exhibition was mounted. But once the agitation had subsided a little, all the paintings still stood in rank and file so that the visitors at the vernissage could have a closer look at them. And with that, let me return to my own opening thought about artistic competition.

There was a lot of talk. The interruption of routine library operations enabled squeaking, laughing, murmuring and other emanations of enterprise and enthusiasm. There were many different languages. It was an international audience. The last contest I would like to mention was taking place inside the viewers’ heads. For some of them, who always felt like making art themselves but couldn’t find the courage, this meant that they remarked with a shrug: “I could have done that.” Great, said the painting this person was looking at: have at it! Why don’t you! Talk is cheap! This painting was sure of its uniqueness. It considered the viewer’s woes to be personal weakness.

Those who had come to the opening event had come out of curiosity or out of friendship or because they were looking forward to absorb the warmth that art provides for free and without which we cannot live. This warmth also benefits all of those who “don’t know anything about art” and who will never acknowledge it (or perhaps they benefit even more than the others, the intimates and makers of art).

Those who had come to the opening event had come out of curiosity or out of friendship or because they were looking forward to absorb the warmth that art provides for free and without which we cannot live. This warmth also benefits all of those who “don’t know anything about art” and who will never acknowledge it (or perhaps they benefit even more than the others, the intimates and makers of art).

Hours later, when the last of the visitors left the library, when the heavy glass door clicked shut, the paintings began to whoop and cheer, and when the jubilation slowly went down, they heard the gentle but clearly audible applause coming from the bookshelves, which sounded as if thousands of leaves were rustling. And this was when the picture exhibition amidst the books, The Imagination of Matter, truly began:

«The imagination is not… the faculty for forming images of reality; it is the faculty for forming images which go beyond reality, which sing reality.»

[Now showing in the library of the Berlin School of Economics and Law: the exhibition "Die Fantasie der Materie" ("The Imagination of Matter", named after one of Gaston Bachelard's books, «L'Eau et les rêves. Essai sur l'imagination de la matière.») with paintings by Carlye Birkenkrahe runs from October 26 to February 23, 2013.][Original post in German]

October 20, 2012

Cherrywood Shingles

[image error] Here is a dream for you: I’m climbing over the roof of a mansion. Oddly enough only parts of it are restored and other parts look lost and rotten. I feel bad for the house and I can’t imagine why someone would fix up one gable but not the one next to it. These gables are very elaborate: a bell shaped copper cover has been placed over each of the upper windows. It looks as if the windows are wearing helmets. But I’m not here to admire the mansion. I’m here to spy upon an attic that I have discovered: a man lives here, a very shy man whom nobody ever sees. When I come to the door of his attic, I’m amazed and impressed by the interior: everything is carved in Cherrywood, and I’m feasting my eyes on the fine detail while at the same time I can’t cross the threshold. I’m staying outside of the room looking inside. Suddenly, a light goes on in the middle of the room and I realize that I have lit a candle by blowing on it. All the time I am afraid the owner might come back and find out if that I’ve looked at his stuff. I retreat, but when I’m already down on the ground far away, I realize that I have left the candle burning and that the man who lives there will know now that I’ve been to his room.

I am dreaming a lot lately but I feel a lot more reticent about my dreams than I used to, even between me, myself and the mirror. Last night I dreamt about xTx the mysterious writer. She was in my kitchen during a party, but she was alone and she was painfully shy and made even me feel shy, which is a very unnatural state for me. Unless I am more shy than I admit to myself. I was grateful to xTx for the experience. She was wearing one of those hipster hats (“slouchy beanie hipster hat”) but I think I told her off for wearing it because after a while she wasn’t wearing it anymore and I noticed her long, thin blonde hair, so much of it in fact that I had a hard time seeing her face behind it. This dream beats the one from the night before where I had dinner with Hitler, Göring (about whom I recently wrote a story) and a third man. The weirdest thing in this dream was that I managed to so manly and enthusiastically shake Hitler’s hand and at the same time salute him the way he liked to be saluted that he congratulated me on my special salutatory skills. Both fascist leaders were wearing uniforms and insignia. There was a third man who looked through me: based on the way I greeted him he instantly figured me for an anti-Nazi and I wondered, before I abandoned this dream, if and how he would betray me to the others. I wasn’t afraid, not very anyway. It’s good to have dreams again though I could do with a little less celebrity craze.

I am dreaming a lot lately but I feel a lot more reticent about my dreams than I used to, even between me, myself and the mirror. Last night I dreamt about xTx the mysterious writer. She was in my kitchen during a party, but she was alone and she was painfully shy and made even me feel shy, which is a very unnatural state for me. Unless I am more shy than I admit to myself. I was grateful to xTx for the experience. She was wearing one of those hipster hats (“slouchy beanie hipster hat”) but I think I told her off for wearing it because after a while she wasn’t wearing it anymore and I noticed her long, thin blonde hair, so much of it in fact that I had a hard time seeing her face behind it. This dream beats the one from the night before where I had dinner with Hitler, Göring (about whom I recently wrote a story) and a third man. The weirdest thing in this dream was that I managed to so manly and enthusiastically shake Hitler’s hand and at the same time salute him the way he liked to be saluted that he congratulated me on my special salutatory skills. Both fascist leaders were wearing uniforms and insignia. There was a third man who looked through me: based on the way I greeted him he instantly figured me for an anti-Nazi and I wondered, before I abandoned this dream, if and how he would betray me to the others. I wasn’t afraid, not very anyway. It’s good to have dreams again though I could do with a little less celebrity craze.

[image error]I have a craving for a Danish cracker with Nutella on it. The cracker feels healthy, the Nutella is a chocolate spread stuffed with chemicals. It makes me happy in a straightforward way which does not depend on my daily word quota. I have exceeded that quote for today by writing up my dreams and doing that has brought out a few scenes that I had no idea had been slumbering under my storytelling tongue.

Photo: the Bosnian mountain village of Lukomir famous for its cherrywood roof-tiled houses. Not a place to be at night. Vampires abound.

October 13, 2012

“Muscles and sex” at the Frankfurt book fair

The e-book seems to small a concept to me sometimes. My writer’s heart refuses to beat in the new pithy rhythm dictated by the digital. Likewise, the Frankfurt book fair, the largest event of its kind in the world, seems too large an event to me. Even from a distance I cower. The low-key announcement of the Swedish Nobel prize for literature serves as an anti-dote: there’s very little marketing in Stockholm. They’ve got a dynamite king, they don’t need billboards. Swedes don’t even need muscles: the guy who reads the announcement looks like a bureaucrat who feels guilty to cause such a fuss. He’s only giving one million dollars away to a Chinese writer that I’ve never heard of, but who is said to have been born in a small, poor Chinese village. I’m grateful that such a story surrounds the prize, not just fruit flies.

The e-book seems to small a concept to me sometimes. My writer’s heart refuses to beat in the new pithy rhythm dictated by the digital. Likewise, the Frankfurt book fair, the largest event of its kind in the world, seems too large an event to me. Even from a distance I cower. The low-key announcement of the Swedish Nobel prize for literature serves as an anti-dote: there’s very little marketing in Stockholm. They’ve got a dynamite king, they don’t need billboards. Swedes don’t even need muscles: the guy who reads the announcement looks like a bureaucrat who feels guilty to cause such a fuss. He’s only giving one million dollars away to a Chinese writer that I’ve never heard of, but who is said to have been born in a small, poor Chinese village. I’m grateful that such a story surrounds the prize, not just fruit flies.

I’m reading an article in a German newspaper about the book fair. It is incredibly whiny and self-involved while lamenting how incredibly whiny and self involved the Frankfurt literary scene is. The author identifies “muscles and sex” as the lowest common thematic denominator of this fair. It begins with the sentence: “The book fair is a sadomasochistic game.” I don’t understand half of what this journalist is talking about. I do understand this, however:

I’m reading an article in a German newspaper about the book fair. It is incredibly whiny and self-involved while lamenting how incredibly whiny and self involved the Frankfurt literary scene is. The author identifies “muscles and sex” as the lowest common thematic denominator of this fair. It begins with the sentence: “The book fair is a sadomasochistic game.” I don’t understand half of what this journalist is talking about. I do understand this, however:

“So serious, you take your books so incredibly seriously,” says the young editor from Manhattan: he thinks it’s charming. Writer Richard Ford adds that the readers who wanted his books autographed tracked him down almost brutally, adds writer Richard Ford. Obviously, the people [in Germany] are “fanatical” when it comes to books. No wonder, he says, intellectuals and artists are supposedly a lot more influential in society than in America.

[From an article by Mara Delius in the German newspaper "Die Welt", October 13, 2012, my translation.]

[image error]Again, there’s a story here, and politics, too, but the story is in the foreground: a famous writer is hunted down by his European fans. He’s ambivalent, tickled in his narcissism, too, but there’s something of the wolf in these German fans and their fangs. The Manhattan editor on the other hand is obviously just a fool. For the sake of his clients, one hopes that he will be able to muster up some seriousness when it comes to their work. Both statements do indeed reveal a degree of anti-intellectualism for which the US is known, alas. But the brutish fans and the journalists hungry for a story surrounding the fair are not really pro-intellectual either: they don’t attend to literature, they attend to the marketplace. Everybody talks about the money, few talk about the morals. As a commodity, digital or print, the book is as successful as ever, if not more. By comparison, the writer is a lousy commodity. A cynical observer might infer that the best writer is a dead writer as far as the market is concerned: maximum control at minimum cost.

But we’re not being cynical in this venue, of course not. The cynical observer, the serious writer, the young editor, the harangued best-selling author, they all are wonderful protagonists in a story, any story. Writing is maximum control at minimum cost, too.

October 8, 2012

that devil of denial

A group therapist someone told me about keeps it all very calm and quiet but encourages histrionic outbursts of his clients: he even helps them summoning the ghosts of their various disorders. But as soon as these ghosts show themselves he assaults them fiercely: using the tools of his trade, he bludgeons them to death, these harmless neuroses and mental misfits. At times it seems to me as if I’m the therapist in this story. I certainly have my fair share of disorders though on the outside I appear cool and collected, as people keep telling me. When I try to impress them with my Freudian slips, my parasympathetic dreams or my miserable moods, they look around as if I’d spoken of someone else altogether. This experience has often put me into a slight state of despair (if such a conjugation makes any sense) because in these moments I feel that I don’t exist: as if the view others hold about me was more important to them than who I really am. Though I recognize that same devil of denial inside me, of course. It delivers ultimate proof that I am indeed neurotic and therefore much more interesting, at the very least to myself, than if I weren’t.

Posted in 100 Days Of Summer. Photo: Optimus on the primal couch.

October 1, 2012

Aller avec Maigret

[image error]Finished Simenon’s (first) Maigret detective novel: somehow I know that I read this one and many others about the inspector from Paris a long time ago. It’s a thrilling tale even though the writing seems often clumsy, take for example the shouting (rather than telling) which is inserted whenever the action is heating up: something like “MAIGRET GUNNED HIM DOWN!” … you can practically hear how every letter is capitalized. What can I learn from this book? For example how inspector Maigret’s physiognomy and nature lend a particular speed to all action so that whenever the plot is accelerating, an attractive gap appears, alongside the question: will this throw Maigret off-balance? At last he loses his cool when his much loved colleague is murdered: from then on the book runs its course like an avalanche. The last 30 pages however are filled with background story and appear like a documentary, oddly disconnected from the plot. Still, the book is most suspenseful and despite its age of 80 years in this somehow still sufficiently contemporary; this could be because we all dream of parents all the time and we’re grateful for every opportunity to teleport to the Seine. Simenon’s references to Paris are strewn in sparsely and smartly, not unlike Chandler’s references to Los Angeles: the city is but a setting, and it’s the reader’s job to discover the uniqueness of this setting. In fact, anything else would feel intrusive. But the true secret of the effectiveness of this novel is not Paris and it’s not the crime either: one could graft Maigret on to another genre (that might be fun in a postmodern way).  The true secret, I think, is the corporeality, which spreads throughout the novel like the inspector’s massive figure. Powerful physicality glows throughout like Maigret’s pipe (which should never burn out) or the potbelly stove in his office (which burns out all the time):

The true secret, I think, is the corporeality, which spreads throughout the novel like the inspector’s massive figure. Powerful physicality glows throughout like Maigret’s pipe (which should never burn out) or the potbelly stove in his office (which burns out all the time):

«Maigret slept, half of his body buried under the red eiderdown quilt, head pressed into the thick feather filled pillow, while all the familiar sounds buzzed around his tranquil face.»

More than in the novels with with Marlowe, Marple or other detectives (not to mention Holmes/Watson), Simenon recruits the reader as a partner in crime in order to protect the firmly established world that turns around Maigret against all evil. In this regard the novels of this French also could also be called “noir” even though they are (politically) far more conservative than their American counterparts.

[This post was first published in German][Photo above: Lucia Joyce dancing in Paris, 1929, Wikimedia; photo below: Jean Gabin as inspector Maigret in L'affaire Saint Fiacre (1959).]