Chris Stedman's Blog, page 11

June 21, 2013

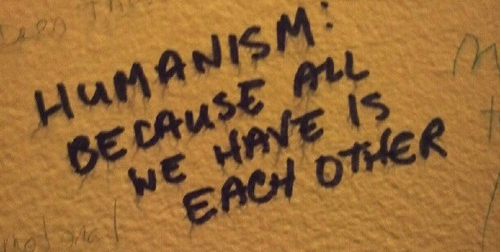

Happy World Humanist Day: A few reflections about Humanism, community, and the future of nonreligion.

Today is the summer solstice. For most people, that just means it’s the longest day of the year and the half-way point of summer. But Humanists have been trying for the last few decades to make something more meaningful of the occasion.

World Humanist Day has been taken as an opportunity to spread and celebrate Humanist ideals. Last year, Chris shared how he came to discover Humanism, but my story isn’t nearly so interesting. I came into undergrad not knowing what Humanism was, then I met the recently-formed Yale Humanist Society at the student activities bazaar and got involved.

Since then, I’ve expressed some frustration about “Humanism” as a label. I didn’t think it was a clear or philosophically substantive position, and ended up believing that we’re better turning towards more conventional forms of moral philosophy to ground our values. 1 I’m starting to become convinced, though, that this fuzziness might actually provide us something extremely important. Chris quoted this definition of Humanism last year:

You won’t ever get a group of nonbelievers to agree on a particular brand of moral philosophy, but you can get just about all of them to agree to something like this. I remember discovering that definition my freshman year of college and being thoroughly enamored by it—it expressed exactly how I wanted to live my life, even if I didn’t have the philosophical background I do now to go deeper.

One thing atheists need to think more about, I think, is what type of world they want to make and live in. What will the average life of a nonbeliever look? How will they relate to religion? What will their community life involve?

We’re getting a lot less religious as a country, 2 so what, if anything, will Americans turn to? Scandinavian countries, I think, can give us an idea. They’re remarkably irreligious, 3 and some recent and fantastic sociological research, primarily by Phil Zuckerman, has explored their beliefs and lives. The Times writes on the topic:

The many nonbelievers [Zuckerman] interviewed, both informally and in structured, taped and transcribed sessions, were anything but antireligious, for example. They typically balked at the label “atheist.” An overwhelming majority had in fact been baptized, and many had been confirmed or married in church.

Though they denied most of the traditional teachings of Christianity, they called themselves Christians, and most were content to remain in the Danish National Church or the Church of Sweden, the traditional national branches of Lutheranism.

At the same time, they were “often disinclined or hesitant to talk with me about religion,” Mr. Zuckerman reported, “and even once they agreed to do so, they usually had very little to say on the matter.”

I think most atheists would laugh at the idea that the future of secularism in American lies in what’s essentially a form of nominal Christianity, but it’s not so outlandish. 4 My only concern is that our culture is much less homogenized than our Scandinavian counterparts, which is why I think Humanism has so much promise.

Humanism is great exactly because it’s not a really substantive philosophical or intellectual position. 5 And that’s fine. Few Christians actively think about the Ten Commandments when acting, just like few atheists think about maximizing utility (and I rarely think about universalizing my maxims. 6 Instead, most people seem to follow a more organic moral decision-making process, usually involving consulting their conscience, their friends, and so on. All we really need, I think, is a socially supportive group to say “hey, we’re here for you and care about you being a good person.”

Thats the promise of Humanism, I think—it’s just vague, fuzzy, and feel-goody enough to match the Danish National Church in sustaining a broad community that’s supportive, positive, and human. Humanism can be something people from any cultural background, be it Jewish, Muslim, or Christian, can reach to as their beliefs soften.

Otherwise, we may very well end up looking more like the Scandinavian nations, at least in terms of our attitude towards religion and religious identities. Maybe Humanism will never catch on, and future secular Americans will simply stay within the nominal identity of whatever religious traditions they were raised in. They’ll celebrate Christmas without Christ, go to Church without praying to anyone, and shy away from the word “atheist” altogether.

Personally, I’ll probably always celebrate Christmas, and my kids will celebrate Christmas. I don’t expect any secular Christian churches to pop up any time soon, though. So in the mean time, however the future of American religion looks, Humanism can do some real good and provide some real community to nonbelievers. That, at least, makes me proud to say I’m a Humanist.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Notes:

Feel free to read my ongoing series on morality to get more of my thoughts about how atheists ought to go about answering moral questions. ↩Though, it’s worth noting, belief in God has barely risen at all in the last ten years. Religion is softening, not going away. ↩About 1/3 of Danes believe in neither a God nor a universal spirit, which is basically unheard of in any other geographical region. ↩I actually have a lot of trouble imagining New Atheism as anything but a somewhat marginal and reactionary position. I’d be amazed to see it gain broader cultural relevance. ↩I’m basically just trying to piss off New Atheists and Humanists at the same time right now. ↩I’m a bad neo-kantian ↩June 17, 2013

Sunday Assembly in NYC

Heads up to readers in the NYC metro area: Pippa Evans and Sanderson Jones, British comics and cofounders of atheist community congregation The Sunday Assembly, will be bringing one of their assemblies overseas to the Tobacco Road dive in Manhattan.

The Assembly, described by the founding couple as a “friendly community gathering for like-minded people”, draws generously from the structure of religious ceremonies in their Order of Service. Each congregation features several songs (Jones holds music to be very important to the “celebration of life”) interspersed with a guest speaker and a reading. Evans and Jones have been working to spread the movement internationally by offering guidelines with which people can start their own assemblies, and given the unexpected response they’ve received, they’ve fundraised to travel to NY and help kickstart a local assembly there.

For more info on the Assembly, you can visit their website, or watch the video below to get another taste of the experience:

If you’re thinking of going, tweet us at @NPSBlog and we’ll connect you with other NPS fans planning on attending!

Walker Bristol is a nontheist Quaker living in Somerville, Massachusetts. A rising senior at Tufts University reading religion and philosophy, he covers social activism and class inequality in the Tufts Daily and has worked in on-campus movements promoting religious diversity, sexual assault awareness and prevention, and worker’s rights. Formerly, he was the Communications Coordinator at Foundation Beyond Belief and the president of the Tufts Freethought Society. He tweets at @WalkerBristol.

June 15, 2013

Moral Naturalism Part 2: Non-naturalism demystified

I described Thursday my frustration with what seemed to be a common moral view among atheists—roughly, that moral naturalism is true because facts influence our moral decisions, or because morality is intimately connected to the natural world. This doesn’t follow, though. Aerodynamics and weather conditions can tell an archer how best to aim, but it’s a mistake to suppose it tells an archer equally well where he ought to aim. The former are descriptive and natural concerns, the latter are normative or prescriptive concerns.

Atheist proponents of moral naturalism seem to spend a time talking about how science can help inform our moral decisions, 1 but seem to skip over entirely the interesting (and relevant) issue of how science tells us what we should aim for.

With that out of the way, I’d like to turn today to address a more plausible philosophical framework for atheists to discuss morality—moral non-naturalism. This isn’t the most intuitive concept, but it’s not as strange as it might seem. It doesn’t mean that facts or nature are morally irrelevant, and it doesn’t mean that supernatural things must exist. 2 I think it’s best understood by analogy.

Non-natural normative truths without God.

Any natural property we can point to—say, maximizing pleasure—can’t overlap with something like the good, because “good” is a normative property. The would-be naturalist must show how nature can account for the normative property of morality, but this seems implausible—you can’t seem to point at any collection of atoms and say “there, those are ‘oughts.’”

This lends many people to believe that atheism must entail nihilism—the famous paraphrase from Dostoevsky applies, “without God, all is permitted.” 3

But this argument won’t work if normative truths can exist independent of God and nature. If we can show how something like this might exist, we can have a model for how morality might look. Consider the law of excluded middle in logic. 4 This is a law which holds that something is either true or it isn’t—there’s no in-between.

The law of excluded middle tells us that, if we know that it’s not the case that a preposition “p” is false, then we ought to believe that p is true. It seems trivial enough to say, but it’s an important facet of first-order logic. Notice, though, that it’s normative—it tells us about something we ought to believe or do. Notice, also, that it’s not really in any coherent sense natural—you can’t seem to point to any atoms in the world and say “there, there is the law of excluded middle.” And notice, too, that no theist to my knowledge has ever said that “without God, no middles are excluded.” It seems that it’s plausible, if not possible, for non-natural normative truths to exist with no grounding at all in God.

Logic and morality are disanalogous in many important and relevant ways, but this example simply shows first, that it’s plausible that these types of normative truths can or do exist; and second, that something like the law of excluded middle might be a good candidate for how moral normativity might look.

So what does a non-natural morality look like?

It’s a tricky philosophical problem to tackle whether or not something like this actually exists. 5 It’s surprisingly hard to pin down what this actually means, but moral non-naturalism doesn’t require believing in anything spooky. So long as it’s true that 2+2 = 4, it doesn’t seem particularly relevant to me whether numbers like “2″ or things like “+’s” really exist. I only care about whether the statement is true, what I should believe, and how I should act given that knowledge. Similarly, I’m not concerned whether the law of excluded middle exists, nor am I too worried whether moral truths are things that are floating around in nature. What I do care about is whether those moral statements are true, and that’s the question I think is most relevant and important for moral realists to address.

As for what non-natural moral truths actually are, here I can’t provide much more than a suggestion to survey contemporary moral philosophy and see what you find compelling or plausible. I personally find Neo-Kantian systems to be fairly persuasive, 6 but you might not. You might prefer John Rawls’s or Stephen Darwall‘s brands of contractualism, Derek Parfit’s chimeric moral theory, or something else entirely. I’m not too interested in presenting and defending any particular moral theory, 7 but instead simply make the point that this is a more promising framework for our moral discussions which avoids the obvious pitfalls of moral naturalism that so many atheists seem to simply (and embarrassingly) ignore.

What if I’m not convinced?

Since I’m talking frameworks and not specifics, it’s important to point out that it might very well be the case that the moral skepticism is right—maybe moral truths don’t actually exist. Or maybe they do exist, but relativism is actually true. 8 I’ll also happily admit that it’s possible for moral naturalism to be true—there are some more-or-less plausible and sophisticated arguments that I glossed over which I think provide a more promising framework for natural accounts of normativity. I’ll turn to all of these issues in the next few posts.

In Part 3, I’ll address the possibility of moral nihilism, and explain how I’m okay with the idea on my more skeptical and cynical days. Part 4 will address alternate moral theories and more plausible versions of naturalism for any readers who might not be satisfied by non-natural accounts but still want to avoid the obvious failures of more unsophisticated theories popularized by positivist-minded atheists. I’ll wrap everything up with Part 5, while giving what I think is some more practical and less abstract advice for an atheist who wants to treat morality with some seriousness.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Notes:

It’s worth noting that I don’t know of any moral philosopher who has argued that facts are irrelevant to moral decisions. ↩I remember talking with my intro ethics professor after The Moral Landscape came out, and he tried to explain to me what moral non-naturalism was and I got really hung up on this point. ↩It’s also worth noting that this is fairly incoherent. “Permission” is a moral concept, so if the point is meant to be that morality doesn’t exist without God, then nothing in fact is permitted—just as nothing is forbidden. Things just are. ↩For readers with a more sophisticated understanding of logic: Yes, it gets much more complicated. Yes, I know this isn’t true in many logical systems. Yes, it still works as a good example. If you feel the need to rant about how it doesn’t hold in other logical systems, replace it with a more sophisticated law of your choice. ↩In no small part because it’s philosophically tricky to even understand what “existence,” or an “object,” or any-other-thing-that-seems-really-basic actually is. ↩I’d recommend some Christine Korsgaard for Neo-Kantianism with a nice Aristotelian twist. ↩Though I’m happy to make suggestions to any interested readers in the comments. ↩For all I’ve been knocking on The Moral Landscape, I will admit the best part of his book was a polemic against relativism. I just wish Harris didn’t manufacture the blatantly false-choice between moral relativism, morality from ancient texts, or his ill-supported pet moral theory. ↩June 13, 2013

Moral Naturalism Part 1: An untenable framework

This is part one of a series where I lay out some of my thoughts about and frustrations with contemporary ethical debates in the atheist movement. I’ll be occasionally editing and refining and clarifying as appropriate. Part 1 will explain my problems with moral naturalism. Part 2 explains why I think non-naturalism is a more plausible framework, while sketching out a rough picture of what non-natural normative truths independent of God might look like. Part 3 will address moral skepticism, as well as why arguments against moral naturalism can also undermine arguments for religion grounded in God. Part 4 will address more plausible forms of moral naturalism for the unconvinced, and Part 5 will provide a summary as well as my general reflections and advice for discussing ethics as philosophically-minded atheists.

I’m not a moral naturalist, and I think just about every attempt I’ve seen from the atheist community to put forward a coherent version of moral naturalism is a confused and bizarre failure, at best.

With these next few posts, I hope to provide an alternate perspective for any readers who might have found Sam Harris’s The Moral Landscape compelling, or discuss evolution, common survival, or neuroscience when pressed on metaethics from an insistent believer. These are somewhat understandable mistakes, but based on flawed ideas in both philosophy and science.

I won’t pretend that ethics isn’t hard, 1 but that just gives more reason to avoid the tempting yet shallow answers to moral questions. With any luck, this won’t be an intensely abstract and hard-to-follow post, but the trade-off will be that nuanced issues might not be treated as delicately as they might otherwise warrant—I encourage interested readers to explore more formal philosophical resources. 2

What is moral naturalism?

Roughly, moral naturalism is the idea that what’s moral or what’s good is a thing discoverable out there in the natural world, something like a collections of atoms 3 that you can just point to and say “that right there is Morality” or “those atoms are what’s good.”

This seems easy to do with something like chairs, but much harder to do with moral concepts. In fact, we’ve more or less known for a few hundred years that it won’t work. Arguments from Hume to G.E. Moore have more or less made moral naturalism a nonstarter in moral philosophy until a few modern proponents of virtue ethics started arguing (in my opinion, unconvincingly) for the idea.

But contemporary atheists seem enamored with moral naturalism, and this seems to compliment a characteristic overconfidence in what knowledge science can provide. It’s not much of a surprise that an atheist like Lawrence Krauss, who argues that science has more or less made philosophy irrelevant, would square Morality in the natural, and thus scientifically accessible, world.

Why won’t moral naturalism work?

Imagine you’re a typical Utilitarian, and you want to say that what’s good is to maximize pleasure. It doesn’t seem too hard to treat this a natural thing—you can probably point to a few collections of neurons firing just-so in all sentient life and say “There, that’s pleasure. That’s what’s good.” But does that work?

There’s an important difference between what is and what ought to be. This should be a familiar point, and you can call this the is/ought gap, the fact/value distinction, or whatever else you’d like—what matters is that facts tend to be about what exists in the natural world, whereas morality is about what ought to exist in the natural world. But it’s not clear where in the natural world, or where in pleasure, this “ought” is coming from. The fact is that we often do seek pleasure, but should we?

Put another way, if we have all the natural facts about pleasure, we can still respond to someone saying “what’s good is pleasure” by coherently asking “but is pleasure really good? Should we really seek out pleasure?” Notice that this doesn’t work with other kinds of natural definitions. You can’t coherently ask “but is water really H2O?” when you know all the natural facts about water—that’s just what water is, end of discussion. This is G.E. Moore’s famous open question argument. 4

If there’s normativity 5 built into any facts, I’ve yet to see a compelling case. 6 To continue to pick on Lawrence Krauss, in a recent debate he said the following about morality and facts which clearly demonstrates the problem here:

I think science does tell us right and wrong in a real way. For example, the scientific facts that certain animals can suffer, for example, affects our decision of how we should treat those animals—whether we should eat them or not eat them. Or the scientific evidence that certain people of certain colors don’t have different intellects, different capabilities, has changed the way we deal with other humans. Science has determined how we behave in the modern world.

Notice that Krauss gives no scientific justification for “treat equal intellects equally” or “don’t cause suffering.” Of course facts influence moral decisions, since moral decisions necessarily operate over a world of facts. But what’s not clear is that morality itself is based on facts accessible to science. We have no rational reason to suppose it does.

I’ll turn next to why moral non-naturalism is a viable option 7 for a moral realist, and also where scientific accounts of morality, like evolution or neuroscience, can properly fit into our moral understanding.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Notes:

Like, really really hard. ↩The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is always a great place to start. ↩Or fermions and bosons for our particularly reductive readers. ↩Sam Harris briefly treats it in The Moral Landscape by calling it a word game, and suggesting that you can’t coherently respond by questioning whether flourishing of conscious creatures really is good. I hope that strikes you as patently false as it did me. ↩For those less versed in philosophical jargon, normativity is the basically the “ought” property of something. ↩Fun note: The is/ought gap and open question argument apply equally well to any theist who wants to hold that what’s moral is some fact about God. We can just as well ask “Are God’s commands good?” as we can “Is pleasure good?” ↩In fact, I’d argue only option ↩Moral Naturalism Part 1: Dear Moral Naturalists, Stop It.

I’m not a moral naturalist, and I think just about every attempt I’ve seen from the atheist community to put forward a coherent version of moral naturalism is a confused and bizarre failure, at best.

With these next few posts, I hope to provide an alternate perspective for any readers who might have found Sam Harris’s The Moral Landscape compelling, or discuss evolution, common survival, or neuroscience when pressed on metaethics from an insistent believer. These are somewhat understandable mistakes, but based on flawed ideas in both philosophy and science.

I won’t pretend that ethics isn’t hard, 1 but that just gives more reason to avoid the tempting yet shallow answers to moral questions. With any luck, this won’t be an intensely abstract and hard-to-follow post, but the trade-off will be that nuanced issues might not be treated as delicately as they might otherwise warrant—I encourage interested readers to explore more formal philosophical resources. 2

What is moral naturalism?

Roughly, moral naturalism is the idea that what’s moral or what’s good is a thing discoverable out there in the natural world, something like a collections of atoms 3 that you can just point to and say “that right there is Morality” or “those atoms are what’s good.”

This seems easy to do with something like chairs, but much harder to do with moral concepts. In fact, we’ve more or less known for a few hundred years that it won’t work. Arguments from Hume to G.E. Moore have more or less made moral naturalism a nonstarter in moral philosophy until a few modern proponents of virtue ethics started arguing (in my opinion, unconvincingly) for the idea.

But contemporary atheists seem enamored with moral naturalism, and this seems to compliment a characteristic overconfidence in what knowledge science can provide. It’s not much of a surprise that an atheist like Lawrence Krauss, who argues that science has more or less made philosophy irrelevant, would square Morality in the natural, and thus scientifically accessible, world.

Why won’t moral naturalism work?

Imagine you’re a typical Utilitarian, and you want to say that what’s good is to maximize pleasure. It doesn’t seem too hard to treat this a natural thing—you can probably point to a few collections of neurons firing just-so in all sentient life and say “There, that’s pleasure. That’s what’s good.” But does that work?

There’s an important difference between what is and what ought to be. This should be a familiar point, and you can call this the is/ought gap, the fact/value distinction, or whatever else you’d like—what matters is that facts tend to be about what exists in the natural world, whereas morality is about what ought to exist in the natural world. But it’s not clear where in the natural world, or where in pleasure, this “ought” is coming from. The fact is that we often do seek pleasure, but should we?

Put another way, if we have all the natural facts about pleasure, we can still respond to someone saying “what’s good is pleasure” by coherently asking “but is pleasure really good? Should we really seek out pleasure?” Notice that this doesn’t work with other kinds of natural definitions. You can’t coherently ask “but is water really H2O?” when you know all the natural facts about water—that’s just what water is, end of discussion. This is G.E. Moore’s famous open question argument. 4

If there’s normativity 5 built into any facts, I’ve yet to see a compelling case. 6 To continue to pick on Lawrence Krauss, in a recent debate he said the following about morality and facts which clearly demonstrates the problem here:

I think science does tell us right and wrong in a real way. For example, the scientific facts that certain animals can suffer, for example, affects our decision of how we should treat those animals—whether we should eat them or not eat them. Or the scientific evidence that certain people of certain colors don’t have different intellects, different capabilities, has changed the way we deal with other humans. Science has determined how we behave in the modern world.

Notice that Krauss gives no scientific justification for “treat equal intellects equally” or “don’t cause suffering.” Of course facts influence moral decisions, since moral decisions necessarily operate over a world of facts. But what’s not clear is that morality itself is based on facts accessible to science. We have no rational reason to suppose it does.

I’ll turn next to why moral non-naturalism is a viable option 7 for a moral realist, and also where scientific accounts of morality, like evolution or neuroscience, can properly fit into our moral understanding.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Notes:

Like, really really hard. ↩The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is always a great place to start. ↩Or fermions and bosons for our particularly reductive readers. ↩Sam Harris briefly treats it in The Moral Landscape by calling it a word game, and suggesting that you can’t coherently respond by questioning whether flourishing of conscious creatures really is good. I hope that strikes you as patently false as it did me. ↩For those less versed in philosophical jargon, normativity is the basically the “ought” property of something. ↩Fun note: The is/ought gap and open question argument apply equally well to any theist who wants to hold that what’s moral is some fact about God. We can just as well ask “Are God’s commands good?” as we can “Is pleasure good?” ↩In fact, I’d argue only option ↩New Religion Newswriters Association Resource on Nontheists

Religion Newswriters Association—a non-partisan service for journalists who write about religion provided by journalists who write about religion—lifts up Faitheist in the introduction to their new resource entitled “Freethinkers: The next generation of nontheists emerges.”

“Others argue for greater engagement with believers – for finding ‘common moral ground between theists and atheists,’ as Chris Stedman, a humanist chaplain at Harvard University, puts it. Stedman is the author of the 2012 memoir Faitheist, which is often a term of derision used by atheists for other nonbelievers who they say try too hard to accommodate belief.”

Click here for a list of what the RNA sees as the top emerging stories and studies about young nontheists, as well as some of the leading nontheist organizations, scholars, and resources. What do you think about the issues that they’ve highlighted? Is there anything not listed that you would have included?

June 12, 2013

Darryl Stephens Comes Out as Agnostic

Actor and LGBT activist Darryl Stephens (star of TV’s “Noah’s Arc”) has publicly come out as agnostic after reading Faitheist. Click here to read his vulnerable, honest reflection on his journey and his desire to find common ground with the religious.

Actor and LGBT activist Darryl Stephens (star of TV’s “Noah’s Arc”) has publicly come out as agnostic after reading Faitheist. Click here to read his vulnerable, honest reflection on his journey and his desire to find common ground with the religious.

“[Faitheist] has inspired me to be less judgmental of people of faith… The kindness one exhibits, the empathy one feels, the integrity with which one lives their life – these are the qualities that we should be concerned about, not where he or she spends their Sunday mornings… No one has all the answers. And just because we’re reading different books doesn’t mean our stories won’t overlap at times and that we can’t find strength and solace in our similarities.”

June 7, 2013

A Queer Atheist in the Heart of Mormon Country

Earlier this year I visited Utah to speak at a conference cosponsored by Brigham Young University (98.5% Mormon) and Utah Valley University (86% Mormon, the highest single-religion percentage at any public university campus in the U.S.A.). In advance of my speech this weekend at Boston Pride, and in light of a strong Mormon presence at this year’s Utah Pride, my new piece for Religion Dispatches explores what I experienced as a queer atheist in the heart of Mormon country. Check out an excerpt below and click here to read it in full.

Last weekend a group of around 400 Mormons marched in the Utah Pride Parade. Calling themselves “Mormons Building Bridges,” they were met with enthusiastic applause. Carrying signs with messages like “Love 1 Another” and “LDS heart LGBT,” they were there to show their support for the LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) community and celebrate recent advancements in issues relating to LGBTQ people and Mormons, such as Bishops no longer excommunicating members who come out and the Boy Scouts of America voting to allow openly gay scouts to participate. (LGBTQ adults and atheists still cannot do so openly.)

As I read about Utah Pride in preparation for my remarks this upcoming weekend as the 2013 Boston Pride interfaith speaker, I couldn’t help but reflect on what I learned during a recent visit to Utah.

It was late in the evening when I arrived, and I knew I would be there for only 24 hours. I was met by Alasdair Ekpenyong, a college sophomore who stands at the crossroads of intersecting identities and convictions: black, LGBTQ-affirming, feminist, progressive, a lover of bowties—and deeply Mormon.

The implosion of r/atheism: What Reddit can tell us about building community

Many readers may have noticed a commotion surrounding recent changes on Reddit’s atheism forum. Matt Guay contributes a guest post to discuss what implications this may have for atheist communities.

I think it’s important to be upfront with my biases. Readers familiar with Reddit’s atheism community, r/atheism, may not be surprised to learn that I think it exemplifies many negative aspects of modern atheism—hatred, prejudice, and belief by cultural conformation rather than rational inquiry. Many might disagree, but I don’t wish to address those arguments here. Instead, I want to hold up r/atheism, or at least my version of r/atheism, as an instructive model of the challenges we’ll face as Western populations increasingly shed religious belief and look to new cultural identities.

For those of you who don’t know (and don’t worry, you haven’t missed much), r/atheism is one of the most popular forums on Reddit, with over two million subscribers. The subreddit is a content aggregator, where users can, in a democratic upvote and downvote system, submit and curate content pertaining to atheism, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, and overbearing parents who just don’t understand.

Yesterday, r/atheism was engulfed in outrage over a new change in moderation policy. The crux of the controversy is that a new policy prevents direct image links from being posted, emulating several other Reddit communities in preventing low-content “memes” and image macros from dominating the forum.

The drama that unfolds was a juicy bit of schadenfreude for many observers, with popular outcry seemingly disproportionate (in my mind) to the new policies which have gained popularity within other subreddit communities. Popular threads, upvoted to the front of the r/atheism forum, included:

So, yes, the largest atheist community on the internet is in an unprecedented outrage because content, such as these (all of which were found in r/atheism’s top-rated posts), will be two clicks away, instead of one. To quote one irate commenter: “If this subreddit is not open and free, then I honestly don’t see the point. Socrates died for this shit and we’re taking it too lightly.” Your opinion may vary.

Now, two things are true. First, I deliberately picked some of the more over-the-top and dramatic responses to share here. There were naturally many shades of opinion in such a large and diverse community, and certainly many redditors (mostly outside r/atheism itself) strongly approved of the changes. Second, r/atheism has more content than the vapid images that I have shared here, and browsing through that list of top-rated posts will reveal as much.

It remains true, however, that a significant portion of this rather large atheist forum exhibited responses in line with the sentiments I’ve highlighted. And substantive as the content might occasionally be, hollow content tends to gain popularity due to simplicity, humor, and mass appeal. As witnessed with the growth of television in previous decades, mass popularity, especially coupled with Reddit’s democratically dictated content, ends up favoring simple, easily parsed material that’s promoted at the expense of more in-depth discussion and analysis. Several of Reddit’s larger communities are struggling to tip the balance in the other direction, experimenting with new rules akin to the new r/atheism policies.

What is troubling for r/atheism in particular is that the tone of this content often reflects pervasive anger, self-righteousness, and a sense of inherent superiority over believers, reinforcing stereotypes already leveled against the broader atheist community. That so many r/atheism members fought to defend this content specifically is an unsettling indication of the values that many who wear the label “atheist” possess.

It is therefore valuable for us to take a look at what is happening here, not because any of this petty drama is intrinsically interesting, but because it highlights that atheist communities are not immune from the ugliest aspects of religious communities—r/atheism’s hatred, intolerance, dogma, and us-vs-them mentality with regards to religion as a whole seems to directly hinder the causes of effective social action and accessibility to group nonmembers.

This is a broader incrimination than this moderation spat calls for, but these have been common complaints for some time. One doesn’t need to look much further than what other atheists on Reddit have been saying about r/atheism to notice this. I recognize that atheists living in more fervently religious communities may feel more tangibly a sense of conflict with organized religion, and that being surrounded by nonbelievers has made it easier for me to make peace with my Christian upbringing. It is easy to forget how infuriating actual interaction with those who use their religion as a cudgel can be, and it may be reasonable that people use online communities to vent. Still, there is no denying that r/atheism is widely criticized, even by other atheists, for its overt hostility and alienation of outsiders.

For anyone interested in the future growth of a new secular or humanist culture, it’s a valuable observation that just shedding religion does not cause religion’s problems to go away. These problems seem related only to the scale and popular appeal of a community, not its underlying ideology (one could make a similar case for r/politics, and I don’t even want to begin wading into pinning down connections with real-life pop cultures).

As the God issue is settled, we must be able to move past our anger with religion if we are to create a new, positive, constructive dialog with the population at large. We must begin to address the question of what to do in religion’s wake. Part of this challenge will be grappling with the sociological forces that seem to pervade large ideological communities, both religious and otherwise.

Of course, one cannot draw exact correspondences between the behavior of an online community and the more complex behavioral norms adopted over time by real-world cultures, but if we are to make any true societal progress and not lapse into a new dogmatic social institution, online communities provide ample data and simplified first steps into the complicated arena of understanding the forces which shape the emergence of these pathological social behaviors.

If emerging secular culture is to escape the pitfalls of scale and mass popularity, its members must be proactive in taking measures to prevent it. I can’t say how best to do this, and social theories have had little success so far in arriving at accurate prescriptive recommendations for such issues. But it must start by observing that we are not immune to the problems of the past, and it must continue with inquiry into what factors shape these sociological forces.

Moreover, we can hope to do better than the scholars of our past. Rationalism and empiricism have provided us deep insights into the workings of the world around us, and these tools are being extended past the physical sciences. Cognitive scientists such as Daniel Dennett, Jesse Prinz, and Jonathan Haidt, as well as evolutionary biologists such as David Sloan Wilson, have already begun explorations of theories of culture as complex adaptive systems, and I believe these tools will gain increasing prominence as research progresses and advances in cognitive neuroscience clarify theoretical underpinnings – I’m looking at you, memetics. We are in a unique position in history, for the first time developing the analytical tools to understand complex social systems and possessing far more data from those systems than at any time before. From this perspective, r/atheism is a canary in a cultural coal mine, and we should embrace the opportunity to study the illness if we ever wish to successfully grapple with the organizational challenges of a real-world movement.

Matt Guay is a graduate student studying mathematics and neuroscience at University of Maryland, College Park. In addition to research in those areas, Matt enjoys learning more about evolutionary psychology and sociology, as they bring together modern theories of complex systems and the real-world problems they aim to tackle.

Matt Guay is a graduate student studying mathematics and neuroscience at University of Maryland, College Park. In addition to research in those areas, Matt enjoys learning more about evolutionary psychology and sociology, as they bring together modern theories of complex systems and the real-world problems they aim to tackle.

June 3, 2013

Religious Liberty and LGBT Rights

On Monday, June 10, from 6-7pm eastern, Becky Garrison will host a webinar about religious liberty with a focus on LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) issues, a conversation important to both people of faith and nontheists. I will be joining Becky on this webinar, along and Ed Buckner, former President of American Atheists and author of In Freedom We Trust, and other invited guests.

Relatedly, June 10th happens to be the 216th anniversary of the proclamation of the famous Treaty with Tripoli that clarifies what the Founding Fathers thought about the merger of church and state. And this year marks the 350th anniversary of the signing of the RI state charter, which has the distinction of being the first governmental charter to write religious liberty into law.

This event is free but reservations are required. To RSVP go to this link.