Andy Worthington's Blog, page 138

June 2, 2013

Remembering a Death at Guantánamo, Six Years Since I Began Writing About the Prison as an Independent Journalist

Please support my work!

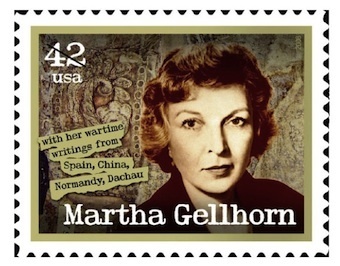

Six years ago, on May 31, 2007, I posted the first article here in what has become, I believe, the most sustained and comprehensive analysis of the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo that is available anywhere — and for which, I’m gratified to note, I was recently short-listed for this year’s Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism. In these six years, I have written — or cross-posted, with commentary — nearly 2,000 articles, and over 1,400 of these are about Guantánamo.

I had no idea it would turn out like this when I began writing articles about Guantánamo six years ago. I had just completed the manuscript for my book The Guantánamo Files, which consumed the previous 14 months of my life, and which was published four months later, in September 2007.

I was wondering how to follow up on the fact that I had lived and breathed Guantánamo almost every waking hour over that 14-month period, as I distilled 8,000 pages of US government allegations and tribunal and review board transcripts, as well as media reports from 2001 to 2007, into a book that attempted, for the first time, to work out who the men held at Guantánamo were, to explain where and when they were seized, and also to explain why, objectively, it appeared that very few of them had any involvement whatsoever with international terrorism.

As I was wondering how to proceed, I received some shocking news. A Saudi at Guantánamo, a man named Abdul Rahman al-Amri, had died, reportedly by committing suicide. I knew this man’s story and decided to approach the Guardian, explaining who I was and why I felt qualified to comment, but when I was told that they weren’t interested, and would be getting the story from the Associated Press, I realized that the WordPress blog that my neighbour Josh had set up for me, initially to promote my books, provided me with the perfect opportunity to self-publish articles, and to see what would happen.

That first article is here, and I’m cross-posting it below, as a reminder of where it all began, as well as to remember Abdul Rahman al-Amri, and the eight other men who have died at Guantánamo. Two days after, I published a follow-up article, also cross-posted below, and I published reminders of his death on the 1st anniversary in 2008 (“The forgotten anniversary of a Guantánamo suicide“), on the 2nd anniversary in 2009, and on the 3rd anniversary in 2010.

There have long been profound doubts expressed about most of the alleged suicides at Guantánamo — and particularly of the three men who died in June 2006, Abdul Rahman al-Amri Al-Amri in 2007, and Mohammed al-Hanashi in June 2009. The supposed “triple suicide” in June 2006 was the subject of an excellent report by Scott Horton in Harper’s Magazine in January 2010, based, in particular, on the testimony of Staff Sgt. Joe Hickman, who disputed the authorities’ story (and also see my articles here and here, and my discussion of Erling Borgen’s film “Death in Camp Delta”). There had also been doubts about al-Hanashi’s death (see here, here and here), but little had been done regarding al-Amri’s death until my friend and colleague Jeff Kaye wrote an article in February 2012, based on their autopsy reports, which I cross-posted, with my own commentary, as “Were Two Prisoners Killed at Guantánamo in 2007 and 2009?”

I hope you have time to read the articles below, in memory of Abdul Rahman al-Amri, whose death — and subsequent demonization by the US authorities — started my career as a full-time journalist and activist on Guantánamo. Many of the themes I touched upon back then — dealing with inadequate information masquerading as evidence — are still, I’m sad to note, relevant today, providing another compelling reason for Guantánamo to be closed, and for nothing like it to be attempted again. For a detailed analysis of his story, see the first entry in this article I wrote last May, as part of my ongoing project to analyze the classified military files relating to the prisoners in Guantánamo, which were released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, and on which I worked as a media partner.

Suicide at Guantánamo: the story of Abdul Rahman al-Amri

By Andy Worthington, May 31, 2007

According to the Associated Press, the Saudi citizen who apparently committed suicide at Guantánamo on Wednesday 30 May has been identified by the Saudi authorities as Abdul Rahman al-Amri. Described by the Pentagon as a 34-year old from Ta’if, born on 17 April 1973, al-Amri had been held in the maximum security Camp V, reserved for the “least compliant and most ‘high-value’ inmates”, according to a US military spokesman.

Whether or not this is a valid description of al-Amri is debatable. He did not take part in any of the tribunals at Guantánamo –- either the Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRT), convened to assess the status of the prisoners as “enemy combatants”, or the annual Administrative Review Boards (ARB), convened to assess whether the prisoners still constitute a threat to the US and its interests. He did, however, prepare a statement for his CSRT in which he “admitted it was his duty to fight jihad and that he continues to admit to that today. He says it is all Muslims’ responsibility to fight for jihad when called upon by a Muslim government (in this case, and at that time, it was the Taliban)”.

Having served in the Saudi army for nine years, al-Amri apparently travelled to Afghanistan in September 2001, undertook military training at a “school for jihad” in Kandahar and then moved on to the front lines. In December 2001, he passed through the Tora Bora region, crossed the border into Pakistan, and surrendered to the Pakistani police. He was one of approximately 180 Guantánamo prisoners handed over to the US authorities after being detained by the Pakistani authorities during a one-week period in mid-December 2001. Dozens of these men were either humanitarian aid workers or religious teachers, and most of the rest were, like al-Amri, Taliban foot soldiers recruited to fight the Northern Alliance in an inter-Muslim civil war that began long before 9/11. In his statement, al-Amri pointed out that “Americans trained him during periods of his service” with the Saudi army, and insisted that, “had his desire been to fight and kill Americans, he could have done that while he was side by side with them in Saudi Arabia. His intent was to go and fight for a cause that he believed in as a Muslim toward jihad, not to go and fight against the Americans”.

He also refuted the most serious allegation against him: that he “was identified as the person responsible for providing a movie that provided all the details on how the USS Cole was attacked [in 2000] and the explosives that were used”. He admitted that he used the alias Abu Anas whilst in Afghanistan, but explained that he believed that another individual with the same name had been responsible for providing the film. This would not be surprising. Countless prisoners have refuted a variety of allegations based on claims relating to their supposed aliases, and it’s probable — given al-Amri’s stated role as nothing more than a foot soldier against the Northern Alliance — that he was no exception.

Watch the press for the Pentagon’s response to his death, however. Whilst it’s probable that there’ll be more subtlety on display than last June, when the prison’s commander, Rear Admiral Harry Harris, described the suicides of three prisoners as “an act of asymmetric warfare”, it’s likely that someone in the administration will step forward to declare that the USS Cole allegation “proves” that al-Amri — held for nearly five and a half years without charge, without trial, and without access to a lawyer or to members of his family — was an al-Qaeda operative. What will probably not be mentioned is that, according to a report by the imprisoned al-Jazeera cameraman Sami al-Hajj, al-Amri, like the three prisoners who apparently committed suicide last year, had been on hunger strike for several months.

Even in death, it seems, there is no escape from the vengeance of the Pentagon.

Suicide at Guantánamo: a response to the US military’s allegations that Abdul Rahman al-Amri was a member of al-Qaeda

By Andy Worthington, June 2, 2007

More on the apparent suicide of the Saudi prisoner Abdul Rahman al-Amri duly surfaced yesterday. As well as taking part in a hunger strike before his death, it transpires, from a source cited by Arab News, that he had been a hunger striker during the mass hunger strike in 2005, and that, at the time of his death, he was suffering from hepatitis and stomach problems. Where, one wonders, was the much-vaunted medical care for “enemy combatants,” which, in 2005, Brigadier General Jay Hood, the commander of the Joint Task Force in Guantánamo, declared was “as good as or better than anything we would offer our own soldiers, sailors, airmen or Marines”? The answer, as so many other Guantánamo prisoners have noted, is almost certainly that medical care is refused to prisoners who fail to cooperate with the authorities, and that, as one of the “least compliant” prisoners, al-Amri would have received little, if any medical care.

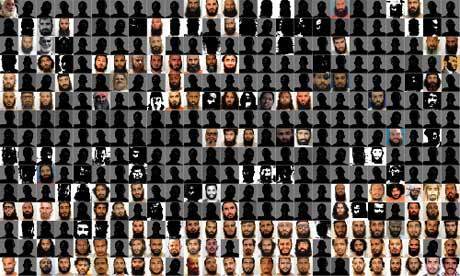

As I warned two days ago, the US authorities have also launched a propaganda campaign portraying al-Amri as a dangerous member of al-Qaeda. In a statement reported by Agence France Presse, US Southern Command claimed, “During his time as a foreign fighter in Afghanistan, he became a mid-level al-Qaeda operative with direct ties to higher-level members including meeting with Osama bin Laden. His associations included (bin Laden’s) bodyguards and al-Qaeda recruiters. He also ran al-Qaeda safe houses.” Quite how it was possible for al-Amri, who arrived in Afghanistan in September 2001, to become a “mid-level al-Qaeda operative” who “ran al-Qaeda safe houses” in the three months before his capture in December has not been explained, and nor is it likely that an explanation will be forthcoming. Far more probable is that these allegations were made by other prisoners –- either in Guantánamo, where bribery and coercion have both been used extensively, or in the CIA’s secret prisons. In both, prisoners were regularly shown a “family album” of Guantánamo prisoners, and were encouraged –- either through violence or the promise of better treatment –- to come up with allegations against those shown in the photos, which, however spurious, were subsequently treated as “evidence.”

As with so many Guantánamo prisoners, the contradictory allegations against al-Amri beggar belief. By his own admission, he traveled to Afghanistan to fight with the Taliban against the Northern Alliance, having served in the Saudi army for nine years and four months. US Southern Command expanded on his activities as a Taliban recruit, claiming that, “by his own account,” he “volunteered to fight with local Taliban commander Mullah Abdul al-Hanan, and fought on the front lines north of Kabul”, and that he subsequently “fought US forces in November 2001 in the Tora Bora Mountains.” This may or may not be true, but it is at least within the realms of plausibility. Claiming that he ran al-Qaeda safe houses, on the other hand, is simply absurd, and should alert all sensible commentators to scrutinize with care the allegations made by the US authorities against the majority of those held in Guantánamo without charge or trial (I’ve studied all of them, and allegations that are either groundless or contradictory are shockingly prevalent).

If we are to believe this callous attempt to blacken the name of a man who, having apparently taken his life in desperation, appears to have made the mistake of traveling to Afghanistan to fight with the Taliban at the wrong time, one question in particular needs answering: when, during the three months that al-Amri stayed in a guest house in Kabul, trained at a “school for jihad” in Kandahar, fought on the front lines, retreated to Tora Bora and crossed into Pakistan, was he supposed to have located the al-Qaeda safe houses that he was accused of running?

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 1, 2013

It’s 28 Years Since Margaret Thatcher Crushed Travellers at the Battle of the Beanfield

[image error]It has become something of a tradition that, on June 1 every year, I add another year to the counter and write an article explaining how many years it has been since the Battle of the Beanfield, and why it is important for people of all ages to recall — or to find out about — the day when, in a field in Wiltshire, the late and unlamented Margaret Thatcher sent a militarised army of police from six counties and the MoD to decommission, with outrageous violence, a convoy of new age travellers, free festival goers, green activists, anarchists and — most crucially — those opposed to the establishment of US nuclear weapons based on British soil. Last year, I wrote, “Remember the Battle of the Beanfield: It’s the 27th Anniversary Today of Thatcher’s Brutal Suppression of Traveller Society,” incorporating an article I wrote for the Guardian on June 1, 2009, and I’m pleased to note that my commemoration of the Battle of the Beanfield a year ago has been liked on Facebook by over 6,700 people — the majority, I believe, since Margaret Thatcher’s death in April.

Unlike the women of Greenham Common, opposed to the establishment of a US cruise missile base on UK soil, who couldn’t be truncheoned en masse for PR reasons, the convoy of men, women and children who had set up a second peace camp at Molesworth in Cambridgeshire in the summer of 1984 could be — and were — evicted by 1,500 police and troops on February 6, 1985, with further violence obviously planned. The Molesworth eviction was the single largest mobilisation of police and troops since the war, and, for the Royal Engineers, their largest operation since the bridging of The Rhine in 1944. Afterwards, the travellers were harried around southern England for four months until their annual exodus to Stonehenge, to set up the anarchic festival that had occupied the fields opposite Stonehenge every June since 1974, when the planned opportunity came for them to be violently attacked, the festival stopped, and the travellers’ movement crippled.

To commemorate the anniversary this year, I’m posting below excerpts from the opening chapter of my book The Battle of the Beanfield, published eight years ago, and still in print, in which my analysis bookends transcripts of accounts by many of the major players. You can, if you wish, buy it from me here.

The first sign of a serious clampdown began at Nostell Priory in the summer of 1984, and as I explained in The Battle of the Beanfield:

At the end of a licensed weekend festival, riot police, who had only recently been suppressing striking miners at the Orgreave coking plant, raided the site at dawn, ransacking vehicles and arresting the majority of the travellers — 360 people in total — with a savagery that had not been seen since the last Windsor Free Festival in 1974. The travellers were held without charge for up to a fortnight in police and army prisons, finally appearing before a magistrate who found them all guilty on allegedly trumped-up charges, and the events of that time are vividly described in a sometimes harrowing and sometimes hilarious account by Phil Shakesby [available here].

Some of the battered survivors made it to Molesworth in Cambridgeshire, a disused World War II airbase that had been designated as the second Cruise missile base after Greenham Common, where they joined peace protestors, other travellers and members of various Green organisations to become the Rainbow Village Peace Camp. In many ways, Molesworth, which swiftly became a rooted settlement, was the epitome of the free festival-protest fusion, cutting across class and social divides and reflecting many of the developments — in feminism, activism and environmental awareness — that had been transforming alternative society since the largely middle class — and often patriarchal — revolutions of the late sixties and early seventies.

One resident, Phil Hudson, recalled the extent of the experiment: “There was a village shop on a double-decker bus, a postman, a chapel, a peace garden, a small plantation of wheat for Ethiopia (planted weeks before Michael Buerk ‘broke’ the famine story in the mainstream media), and the legendary Free Food Kitchen.” The Rainbow Village was finally evicted in February 1985 by the largest peacetime mobilisation of troops in the UK, and the unprecedented scale of the operation, and the effect it had in creating even stronger bonds between the various groups of travellers, are brought to life in the interview with Maureen Stone in Chapter Three [of The Battle of the Beanfield], and in the recollections of Sheila Craig in Chapter Six.

The convoy shifted uneasily around the country for the next few months, persistently harassed by the police and regularly monitored by planes and helicopters. In April they were presented with an injunction, naming 83 individuals who supposedly made up the leadership of the convoy, which was designed to prevent them from going to Stonehenge. As Sheila Craig put it, however, “it was difficult to take it seriously, it seemed meaningless, almost comical, just a bit of paper … So the festival was banned, but we were the festival. It didn’t seem to make a lot of difference, especially as we seemed to be banned anyway, wherever we were.”

Such was the awareness that a noose was tightening around the travellers — through the well-publicised banning of the festival, as well as the constant persecution and the injunction — that even those like the Green Collective, who continued to assert the right of people to attend the 1985 festival, knew that they were effectively drawing up “battle plans.” In the face of the National Trust threatening further injunctions against organisations like Festival Welfare Services and the St John’s Ambulance Brigade if they showed up at Stonehenge, Bruce Garrard wrote in a Green Collective mailing newsletter, “After years of talking about it, this year it seems the authorities will be making a concerted effort to stop the next midsummer festival … but they won’t succeed; what they’ll probably do is to politicise the 50,000+ free festival goers who will arrive there anyway … Thousands of people will be on the move this summer. We’ll all look back and remember the Spirit of ’85.”

As it transpired, people would remember the Spirit of ’85 for far different reasons. On June 1st, after groups of travellers from around the country had stopped overnight in Savernake Forest near Marlborough, 140 vehicles set off for Stonehenge in the hope of setting up the 12th free festival. The atmosphere, as described by many eye-witnesses in the accounts that follow, was buoyant and optimistic. It remains apparent, however — especially in light of the persecution of the previous nine months — that behind this façade lurked generally unvoiced fears. Mo Poole, for example, recalled, in a conversation with Roisin McAuley for an edition of ‘In Living Memory’ that was broadcast on Radio 4 in 2002, that “When the convoy had left Savernake that day, there was a police helicopter that had followed us all the way. There was police everywhere, really. It was obvious to us that we were being followed by the police and that they were monitoring our journey, and therefore I knew that something was going to happen, because they’d never done that before.”

Sid Rawle was so convinced that the state was planning a disproportionate response to the threat posed by the convoy that he stayed behind in Savernake, arguing that if all the travellers stayed put and waited for thousands more people to join them, the authorities would be powerless to break up the ever-growing movement that he had worked for so long to encourage. While it’s also apparent that some of those who set off for Stonehenge that day were prepared for some kind of confrontation, few could have suspected quite how well-armed and hostile their opponents would be. The violent ambush that followed has become known as the Battle of the Beanfield, but it might be better described as a one-sided rout of heart-breaking brutality, and a black day for British justice and civil liberties whose repercussions are still felt to this day.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 31, 2013

EXCLUSIVE: Two Guantánamo Prisoners Released in Mauritania

Note: Please read the comments below for updates. As at 3pm GMT on June 1, there has been no confirmation of the releases. Sources in Mauritania are still saying the men have been freed, but are not yet reunited with their families, while the US authorities are denying it. Some reports claim that only the man from Bagram has been returned home.

Note: Please read the comments below for updates. As at 3pm GMT on June 1, there has been no confirmation of the releases. Sources in Mauritania are still saying the men have been freed, but are not yet reunited with their families, while the US authorities are denying it. Some reports claim that only the man from Bagram has been returned home.

In news that has so far only been available in Arabic, and which I was informed about by a Mauritanian friend on Facebook, I can confirm that two prisoners from Guantánamo have been released, and returned to their home country of Mauritania. The links are here and here.

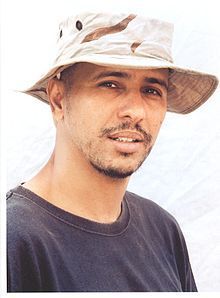

The two men are Ahmed Ould Abdul Aziz and Mohamedou Ould Slahi, and they were accompanied by a third man, Hajj Ould Cheikh Hussein, who was apparently captured in Pakistan and held at Bagram in Afghanistan, which later became known as the Parwan Detention Facility.

According to one of the Arabic news sources, US officials handed the men to the Mauritanian security services who took them to an unknown destination. They have also reportedly met with their families.

I have no further information for now, but this appears to be confirmation that President Obama’s promise to resume the release of prisoners from Guantánamo was not as hollow as many of his promises have turned out to be. It also follows hints, in the Wall Street Journal (which I wrote about here), indicating that he would begin not with any of the 56 Yemeni prisoners out of the 86 prisoners cleared for release by the inter-agency task force that he established in 2009, but with some of the 30 others.

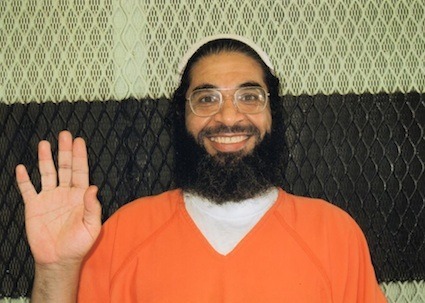

One of these 30 is Ahmed Ould Abdul Aziz, a teacher, and an educated and cultured man, who was seized in what appeared to be a random house raid in Pakistan in June 2002, but the other is a surprise. Mohamedou Ould Slahi was, notoriously, handed over by the Mauritanian authorities to the US in November 2001, He was then rendered to Jordan, where he was tortured, and was then subjected to a specific torture program in Guantánamo, where he arrived in August 2002, after which he became an allegedly helpful informant, although his torture was so severe that it prompted his assigned prosecutor, Lt. Col. Stuart Couch, to resign rather than continue with the case.

Although he had his habeas corpus petition granted in March 2010, this was then vacated by the court of appeals, after an outcry from numerous Republicans, who believed, as had been alleged, that he had been some sort of mentor to the 9/11 hijackers, while he was living in Germany, even though it seems clear that, although he had met them, he had not done anything to assist them in their plans, and nor did he have any knowledge of the 9/11 attacks.

I wrote extensively about the injustice of Slahi’s case — including the self-defeating absurdity of indefinitely detaining someone who had allegedly become an important informant — following the publication of a revelatory article in the Washington Post in March 2010, and his case recently came to light again when Slate published excerpts from an astonishing autobiography that he wrote in Guantánamo.

I will write about further developments when I have them, but for now this appears to be very good news indeed, not just for Ahmed Ould Abdul Aziz and Mohamedou Ould Slahi, but also for the other cleared prisoners in Guantánamo.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

From Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer Tells BBC He Is “Falling Apart Like An Old Car”

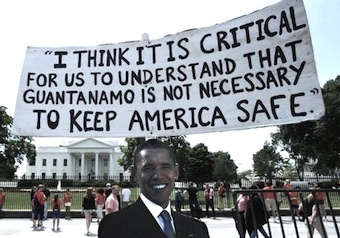

On Guantánamo, despite President Obama’s fine words at a news conference a month ago, and in a major speech on national security last week, we wait and we wait and still nothing happens.

On Guantánamo, despite President Obama’s fine words at a news conference a month ago, and in a major speech on national security last week, we wait and we wait and still nothing happens.

Eight days after he promised to resume releasing prisoners, not one of the 86 prisoners cleared for release over three years ago by the President’s own interagency task force has been freed, and the hunger strike that has been raging for nearly four months shows no sign of slowing. I believe that only the release of prisoners will do that, and yet no one has been released in the last week, even though President Obama can use a waiver in the National Defense Authorization Act to do so, bypassing Congress, which has imposed hideous restrictions on the release of prisoners.

As I explained in an article published here yesterday:

Congress imposed restrictions in the National Defense Authorization Acts of 2012 and 2013, preventing the release of prisoners to countries where even a single released prisoner is alleged to have “returned to the battlefield,” and also insisted that, in other cases, the Secretary of Defense would have to certify that any prisoner the government intended to release would not be able to engage in anti-American activities — a requirement that appears to be impossible to fulfil.

To overcome these obstacles, however, a waiver was included in the legislation, which allows the President and the Secretary of Defense to bypass Congress if they regard it as being “in the national security interests of the United States.”

The easiest prisoner release would be to send Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in Guantánamo, home to his family in London — his British wife and his four British children. Shaker is one of the 86 cleared prisoners, and the British government wants him back — and has been calling for his return since August 2007. Lawmakers can hardly object about releasing a prisoner to the UK, and even if they did, President Obama could use his waiver.

And yet, Shaker Aamer is still held. It is hoped that there will soon be a full Parliamentary debate about his case, following an important backbench debate that took place on April 24 (see here and here), which was triggered by the successful collection of 100,000 signatures on an e-petition to the British government calling for renewed action to secure his release. In the meantime, as I have been reporting regularly over the last few months, he remains a powerful witness from inside Guantánamo of the despair that fuels the hunger strike, and of the violence with which it has been greeted by the authorities. See, for example, my articles, “From Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer Tells His Lawyer Disturbing Truths About the Hunger Strike,” ““People Are Dying Here,” Shaker Aamer Reports from Guantánamo, As Petition Calling for His Release Secures 100,000 Signatures,” “Shaker Aamer, Abandoned in Guantánamo” and “‘Torture is for Torture, the System is for the System’: Shaker Aamer’s Letters from Guantánamo.”

I don’t know what more I could possibly say to express my disgust regarding the vile injustice of the Obama administration continuing to hold Shaker, and the British government — whatever it says it is doing — failing to insist strongly enough about the ongoing imprisonment of a British resident that the US has said it no longer wants to hold, and whose release cannot be prevented by lawmakers.

However, rather than just banging my head against a wall, I’m pleased to be able to post below the extremely moving transcript of an interview the BBC conducted with Shaker, via questions that were put to him by his lawyers at Reprieve, the London-based legal action charity. The BBC Radio 5 Live show is here, but is apparently only available until next week.

BBC interview with Shaker Aamer, broadcast May 29, 2013

Victoria Derbyshire: This morning we hear exclusively the words of the last British resident to be held inside Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. 47-year old Shaker Aamer says he’s “losing his mind and losing his life” inside the high security prison camp. The father of four whose youngest child was born the day he arrived in Guantánamo Bay has been held there for 11 years without charge or trial. US authorities say Shaker Aamer met Osama Bin Laden while he was working in Afghanistan in 2001 and that he led a unit of fighters against Nato troops. But as you’ll hear Shaker Aamer categorically denies either of those took place.

On this programme back in December, we heard how Mr. Aamer is suing the British intelligence services — MI5 and MI6 — over allegations that they were complicit in his alleged torture whilst in Afghanistan. Shaker Aamer confirms this morning to us that officers from the Metropolitan Police have interviewed him regarding those allegations gathering an estimated 120 pages of testimony.

Shaker Aamer has been cleared for release since 2007 by both the last US President George W. Bush and by Barack Obama. The British Foreign Office has told us that securing his release is a high priority for them. He’s been on hunger strike since February this year, along with around 100 of the other 166 detainees.

This is what Shaker Aamer says about his life inside the prison. His words are spoken for him. And the acronym FCE stands for forcible cell extractions.

Shaker Aamer: I am losing my mind, I am losing my health, I am losing my life. They are trying to do as much damage to us as they can before we leave here. They are humiliating us as much as they can. They are harming me as much as they can. For 11 days my heart has been aching very bad. If I sneeze I feel as if there is ice on my heart. It is in my shoulder, on my left hand side. I cannot cough or laugh. It gets a little bit better if I hold my hand on my chest but that does not help much. But without that I feel as though something is going to blow up.

Victoria Derbyshire: Tell us what you want to achieve through your hunger strike?

Shaker Aamer: I have been on hunger strike since February 15th. I am now taking one cup of coffee and one cup of tea a day. I take no sugar in it anymore, no cream and no lemon in it. I don’t want them to say I am not a hunger striker. Even if you put lemon in your tea they will say you are not a hunger striker.

This week they have put me on water bottle loss again as a punishment. They did this before. That leaves me only with the water from the tap which is yellow and which they say is not drinking water.

The hunger strike is a simple matter. It is about justice. There are 86 detainees here including me who have been cleared by the Americans, cleared to leave this place, but they are still here. There are 80 who are not cleared but they have not been tried. It is ironic. President Obama seems to agree with us the place should be closed, so presumably he agrees with our hunger strike.

Victoria Derbyshire: What are relations like with the US military staff there at Guantánamo?

Shaker Aamer: Some of the guards are beautiful people trying to get me to help them with other detainees because they are afraid men will die. Some of the guards are aware of what is happening here. These guards say, “I am sorry, 239.” I honestly forgive them even though what they are doing is wrong.

Not all guards are like that, sadly. People here are dying for lack of a salad. There is a brother on my block with a heart problem. We do not want him on hunger strike as he could not survive it. He needs salad as he cannot eat most of the food they are giving him. So I took the salad they had given me and asked the guard to take it over to his cell. The guard would not do it. In the end though, I managed to get it from the splashbox in my cell to my brother.

I cannot say kind words about the administration now. Captain Robert Durand is their spokesman and I hear from the guards what he is saying on TV. I want this man to come to my cell and speak to me. Please tell him what Detainee 239 says. Everything you are telling the world is totally the opposite of the truth.

Victoria Derbyshire: Have you ever been assaulted whilst at Guantánamo by either staff or other inmates?

Shaker Aamer: Our Prophet told us, “Speak only as people can comprehend, if you want them to understand.” Nobody can understand what it means to be under torture 24/7. It is not just hanging you from the ceiling or being beaten up. It is fighting for hours for a packet of salt. It is beyond explanation. I met with the Metropolitan Police for 3 days in February and told them some of what is happening to me. They had a statement from me that ran to 120 pages, but that is still only one page for every month of my suffering here.

How can the truth be told in such a short time? It’s so senseless, all about trying to break me.

The most I can say is to quote George Orwell in 1984: “The system is for the system, the torture is for torture.”

Victoria Derbyshire: Are there any sanctions that could be put upon you because you’ve spoken out in this way?

Shaker Aamer: What more can they do to me that they have not already done?

Victoria Derbyshire: Can you tell us about your day to day routine?

Shaker Aamer: I am in the psych cell. They want to tell the world I’m crazy. They have a man standing outside my cell all the time, staring at me. He writes everything I do: 239 stood up, 239 sat down, 239 scratched his head. This is every day.

This has been going on for over a month. I came here on April 9th. There is a white woman who comes all the way from the control room and she stands in front of my cell with the other guard. She writes on a piece of paper in front of me. She whispers in his ear. She reads a paper from the file.

“I studied psychology before you were born,” I told her. I know that psychology is a package. Someone has created a whole system and they just follow it. So in response, I write everything they do and send it to my lawyer.

The other day I wanted to dry my shirt after washing it. I hung it on the door. There is nothing else, as it is is the psych cell, so they stop you from hanging yourself. As soon as I did it they told me to take it down. I told them, “You have a camera 24/7. You’re watching me all the time.” But they brought the FCE team. The other brothers on the block argued with them. I knew they wanted to FCE me any way they can. They did it. They FCE me for anything.

I sing to my brothers. Sometimes I sing to the guards. I talk to the guards a lot.

I shout to the other prisoners. I try to lift the spirits. But despite this I am falling apart like an old car. Now the engine of the car is beginning to fail. The heart is really aching. I have not been able to read for a month now. My eyes are going. I cannot remember anything. I forget things. I cannot stand up, I fall down. I don’t want to fall down too much or they will do a code yellow on me when they burst into my cell and step on my hands. They tread on you.

It is cold in here. You might not think so as it is 70.5 degrees. But when you’ve not eaten for 100 days, that’s cold. I try to do exercise in my cell. A brother told me to do gentle things to keep my body warm, but it is hard on my heart and I need to conserve myself.

They took my basic iso [sleeping] mat so it was even colder. I slept without it for 9 or 10 days. Thankfully I got it back.

Victoria Derbyshire: Can you try to describe what it has been like to have been detained at Guantánamo Bay for 11 years without charge or trial?

Shaker Aamer: No. The most I can say is that I have never even met my youngest child, who was born on the very day I arrived into Guantánamo Bay, February 14th, 2002. I have missed my other 3 lovely children for 11 years. I have missed my wife for 11 years. I have missed my life for 11 years.

Victoria Derbyshire: Since 2007 you’ve actually been cleared for release, yet can you imagine leaving Guantánamo Bay?

Shaker Aamer: Yes, and I believe it will happen very soon. But I do fear that when my children call me Daddy I will not respond as I have been called 239 for so long. They may need to call me by a number for a while.

Victoria Derbyshire: Do you believe the British government and the Foreign Office in particular are doing enough to get you released?

Shaker Aamer: It is hard for me to say. For the last month I have not been allowed to see the news. I have never received a letter from the British government. I have even been prevented from writing to William Hague, the foreign secretary. I can only rely on my lawyer for his opinion on this. And it is his opinion that Mr. Hague is sincere in his efforts to secure my release. For that, I thank him. I am not begging for help. I will never beg for help. I demand only justice. But I am very aware of those who offer assistance, and words cannot express my feeling for those who do this of their own free will.

I know that there are dark corners of the British establishment that are working to keep me here. The leaders of the MI6 are doing that. I have a message to MI6. My goal is not to persecute people. Those MI6 in Bagram, Kandahar and Guantánamo, the ones who call themselves John, Lucy and other things. They are under orders. They were doing what they were told. It is not about me wanting revenge on people. I don’t want to do this. Instead, I want to change stuff. We have to stop what is happening. We need to go to the top. We are not looking to the individuals but to the policy since it is the policy that has to change. I want to tell the truth but I don’t want to victimise the MI6 agents. I say this not because I am scared of them. I have principles and I live by my principles. I never wish harm on a human being just because he is doing his job. Even if that job is wrong.

Victoria Derbyshire: What would you say to President Obama who has said on a number of occasions that he would close Guantánamo Bay?

Shaker Aamer: This ugly place is going to close regardless of Obama, regardless of anything. With the help of God we have told the whole world about the injustice of this and now the whole world is with us. So, for Obama it is just a question of how he wants to be judged. Is he a man of his word or is he a liar?

Victoria Derbyshire: What do you believe the future holds for you?

Shaker Aamer: Hmm, I do go back and forth. On the one hand I know I’m going to come home soon. I’m sure of that. On the other, though, they are taking revenge on us in so many ways. I am scared. I am afraid of taking medication from them. It is like a lamb going to the butcher and seeking help. My heart pain is now constant and I don’t want to die in here. When I get out I want to work with KCL [King's College London], with doctors, lawyers, with everyone, to learn the human rights lessons of Guantánamo. It is only by this that we can make sure that we do not do this again.

Victoria Derbyshire: The US authorities have said that they believed that you met Osama Bin Laden while you were working in Afghanistan in 2001 and that you led a unit of fighters against Nato troops. Is that accurate?

Shaker Aamer: I was in Afghanistan for less than 3 months before 9/11. I never met Bin Laden and I never fought America or Nato or anyone else. You have to understand where some of this stuff comes from. There was one detainee here who made up stories on 200 other detainees. He did so so he could get benefits like in the love shack to watch pornographic videos or just something simple, like a packet of cigarettes. He got what he wanted and he has been sent to another country now, while we remain. But I am not angry with him. I don’t agree with him but I understand what he said. Indeed, I even said things against myself when I was being tortured in Afghanistan, so how can I expect anything else?

Victoria Derbyshire: Explain to our listeners why you were in Afghanistan at that time?

Shaker Aamer: I was there with my family and with my friend, Moazzam Begg, and with his family. We were doing charitable work. They are poor people the Afghans, and our religion tells us we must do charity.

Victoria Derbyshire: Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Shaker Aamer: Yes, there is so much I would like to say. But I will say it when I am free.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 30, 2013

Close Guantánamo, Free the Afghans

In the coverage of the ongoing, prison-wide hunger strike at Guantánamo, which is now in its fourth month, there has been widespread recognition that it is unacceptable to indefinitely detain the 86 prisoners (out of 166 in total) who were cleared for release over three years ago by the President’s own inter-agency task force. These men are still held because of Presidential inertia, Congressional obstruction, and the failures of some branches of the US judiciary to uphold justice.

In the coverage of the ongoing, prison-wide hunger strike at Guantánamo, which is now in its fourth month, there has been widespread recognition that it is unacceptable to indefinitely detain the 86 prisoners (out of 166 in total) who were cleared for release over three years ago by the President’s own inter-agency task force. These men are still held because of Presidential inertia, Congressional obstruction, and the failures of some branches of the US judiciary to uphold justice.

56 of these 86 men are Yemenis, and, in some quarters, it has also been accepted that the ban President Obama imposed on releasing cleared Yemenis from Guantánamo, following a failed airline bomb plot on Christmas Day 2009 that was hatched in Yemen, constitutes collective punishment, and is also fundamentally unacceptable because it means that prisoners whose release was recommended by the President’s own task force continue to be detained not because of what they have done, but because of what they might do in future.

Of the 30 others, however, there has been little or no discussion beyond a recognition that one of them, Shaker Aamer, a British resident with a British wife and four British children, could and should be released immediately.

Around a dozen of these 30 men cannot be repatriated, as they are from countries to which it is not safe to return — China, for example, in the case of the three remaining Uighur prisoners (Muslims from Xinjiang province who face government persecution), and war-torn Syria, which has four cleared prisoners.

Others, however, should also be released as soon as possible, given that all that prevents their release is politically motivated obstruction. Congress imposed restrictions in the National Defense Authorization Acts of 2012 and 2013, preventing the release of prisoners to countries where even a single released prisoner is alleged to have “returned to the battlefield,” and also insisted that, in other cases, the Secretary of Defense would have to certify that any prisoner the government intended to release would not be able to engage in anti-American activities — a requirement that appears to be impossible to fulfil.

To overcome these obstacles, however, a waiver was included in the legislation, which allows the President and the Secretary of Defense to bypass Congress if they regard it as being “in the national security interests of the United States.”

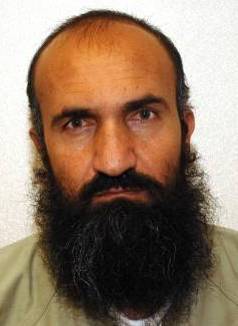

One group of prisoners who might benefit from this waiver are the remaining Afghan prisoners, whose cases I wrote about last year — here and here — when discussions were taking place regarding the possible release of five of the remaining 17 prisoners as part of tentative negotiations between the US and the Taliban.

Those negotiations fell through, but last month David Ignatius revisited the story for an insightful article in the Washington Post entitled, “Keeping Taliban fighters in Guantánamo hurts US interests,” in which he tackled some of the key problems with the “war on terror” that led to the mess at Guantánamo that President Obama has, to date, failed to resolve.

Ignatius began boldly, proclaiming that the “failed effort” to release Afghan prisoners from Guantánamo was an example of how the US government “can work at cross-purposes in dealing with terrorism.” He added, “It shows how an incorrect analysis — that the Taliban and al-Qaeda pose the same threat — can lead to a cascade of bad policy that has undermined US interests.”

The refusal to distinguish between the terrorists of al-Qaeda and the government of Afghanistan at the time of the US-led invasion in October 2001 was a disaster from the start, leading to George W. Bush’s chronically unwise decision to label all the men as “enemy combatants,” and to refuse to grant them any rights at all, either as prisoners or as human beings. More recently, as Ignatius noted, it “complicated the release of five Taliban prisoners from Gitmo during reconciliation talks in 2011; it confounded the Afghan government’s efforts to seek release of eight other Afghans; and it helped fuel a hunger strike described by one prisoner in a recent New York Times op-ed headlined ‘Gitmo Is Killing Me.’”

Ignatius proceeded to explain that the decision by some supporters of Guantánamo to continue to regard all the prisoners at Guantánamo as terrorists, who should be detained indefinitely, is not only wrong, but, in the case of the Afghans, has given the Taliban “a propaganda advantage,” despite CIA assessments that the release of the Afghan prisoners “wouldn’t pose a high security risk.”

Helpfully, Ignatius traces the confusion back to the earliest days of the “war on terror,” through the words of George Tenet, the director of the CIA at the time of the Afghan invasion. He quotes Bob Woodward in his book, Bush at War: “We have to deny al-Qaeda sanctuary, Tenet said. Tell the Taliban we’re finished with them. The Taliban and al-Qaeda were really the same.”

Ignatius continues by explaining that Tenet said he “didn’t view the two as ‘equivalent’ threats,” but adds, “that logic has prevailed ever since, despite skepticism from some CIA analysts as they examined the individual cases.”

As the US began looking at the possibility of releasing Taliban prisoners, after President Obama took office in 2009, his special representative for Afghanistan, Richard Holbrooke, began looking for openings for a political settlement, aware that the Pentagon, backed by Republicans, “opposed any prisoner release that would put Taliban fighters back on the battlefield.”

In April 2009, as Ignatius put it, “Barnett Rubin, an Afghan expert at New York University who would soon join Holbrooke’s team, met with Abdul Salam Zaeef in Kabul.” Zaeef was the Taliban’s former ambassador to Pakistan, who had been held in Guantánamo for three years, and he came up with six names. There was, Ignatius noted, support from former Afghan President Burhanuddin Rabbani, who was in charge of reconciliation efforts for President Karzai.

Rabbani wrote to the US government asking for the release of one of the six, Khairullah Khairkhwa, the former governor of Herat, in early 2011, and this was followed up when Holbrooke’s successor, Marc Grossman, had a secret meeting with a Taliban representative, Mohammed Tayeb al-Agha, which led to a deal involving the proposed release of five Taliban prisoners to Qatar. In return, as Ignatius explained, the Taliban “would condemn international terrorism and release US Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl,” a Taliban prisoner since 2009.

Rabbani wrote to the US government asking for the release of one of the six, Khairullah Khairkhwa, the former governor of Herat, in early 2011, and this was followed up when Holbrooke’s successor, Marc Grossman, had a secret meeting with a Taliban representative, Mohammed Tayeb al-Agha, which led to a deal involving the proposed release of five Taliban prisoners to Qatar. In return, as Ignatius explained, the Taliban “would condemn international terrorism and release US Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl,” a Taliban prisoner since 2009.

Unfortunately, the deal fell through. President Karzai complained that he hadn’t been involved, and when he finally came on board the Taliban had gone off the idea, suspending talks in March last year.

As Ignatius explained, “What made this exercise so frustrating was that the CIA had studied the five Taliban detainees who were slated for release and concluded that this would have no net effect on the military situation, even if they broke their pledges and left Qatar.” Far from being involved with terrorism, the evidence suggested that, although they “had fought with the Taliban, they had no role in supporting al-Qaeda’s plots and had quickly surrendered after the US offensive started.”

After the Taliban withdrew from the talks, President Karzai nevertheless attempted to engage President Obama in further discussions. At the NATO summit in Chicago last May, he asked for the release of eight other Afghans. Their files had also been examined by the CIA, who found that four of them were considered a “low risk” and four were a “medium risk.” As Ignatius put it, however, because of the Congressional requirements covering planned releases from Guantánamo, the Obama administration “made elaborate demands for how the Afghans would be monitored back home,” and Karzai’s government “never bothered to answer.”

Ignatius concluded by noting that the Obama administration “still says it wants a political settlement in Afghanistan, but progress has stalled.” One way to revive it would be for the Afghan prisoners to be released, especially as the Afghan prisoners in Afghanistan — held in the Parwan Detention Facility, formerly known as Bagram — were handed over to Afghan custody in March.

Note: This article was written last Wednesday before President Obama’s speech on national security issues, in which he promised to resume the release of prisoners from Guantánamo. See my coverage here, here and here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

As published exclusively on the website of the Future of Freedom Foundation.

May 29, 2013

Please Support the International Day of Action for Bradley Manning on Saturday June 1, 2013

On Monday (June 3), three years and one week since he was first arrested in Kuwait, the trial by court-martial begins, at Fort Meade in Pfc. Bradley Manning, the alleged whistleblower responsible for making available — to the campaigning organization WikiLeaks — the largest collection of classified documents ever leaked to the public, including the “Collateral Murder” video, featuring US personnel indiscriminately killing civilians and two Reuters reporters in Iraq, 500,000 army reports (the Afghan War logs and the Iraq War logs), 250,000 US diplomatic cables, and the classified military files relating to the Guantánamo prisoners, which were released in April 2011, and on which I worked as a media partner (see here for the first 34 parts of my 70-part, million-word series analyzing the Guantánamo files).

On Monday (June 3), three years and one week since he was first arrested in Kuwait, the trial by court-martial begins, at Fort Meade in Pfc. Bradley Manning, the alleged whistleblower responsible for making available — to the campaigning organization WikiLeaks — the largest collection of classified documents ever leaked to the public, including the “Collateral Murder” video, featuring US personnel indiscriminately killing civilians and two Reuters reporters in Iraq, 500,000 army reports (the Afghan War logs and the Iraq War logs), 250,000 US diplomatic cables, and the classified military files relating to the Guantánamo prisoners, which were released in April 2011, and on which I worked as a media partner (see here for the first 34 parts of my 70-part, million-word series analyzing the Guantánamo files).

To highlight what the Bradley Manning Support Network describes as a trial that “will determine whether a conscience-driven 25-year-old WikiLeaks whistle-blower spends the rest of his life in prison,” an international day of action is taking place on Saturday, June 1. See here for a full list of events worldwide.

At Fort Meade, the day of action will begin at 1pm — see the website here, and sign up on the Facebook page. There will be speakers at 1.30pm, a march at 2pm, and more speakers at 3pm. Speakers “include Daniel Ellsberg, Pentagon Papers whistleblower; Ethan McCord, the soldier who saved the children attacked in the “Collateral Murder” video released by WikiLeaks; Col. Ann Wright, the most senior State Department official to resign in protest of the Iraq war; Sarah Shourd, hiker imprisoned by Iran turned prisoner rights activist; and Lt. Dan Choi, prominent anti-Don’t Ask Don’t Tell activist featured on the Rachel Maddow show.”

In London, there will be a protest outside the US Embassy, beginning at 2pm, which I will be attending. Speakers include: Ben Griffin, a former SAS soldier, who became a conscientious objector and is now a spokesperson for Veterans for Peace UK; Michael Lyons, an Afghan War resister who served nine months in prison as a conscientious objector for refusing to deploy to Afghanistan after reading Bradley’s WikiLeaks releases; the great singer-songwriter David Rovics (whose song for Bradley is here); former UK ambassador Craig Murray; veteran human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell; and photo-journalist Guy Smallman.

Three weeks ago, I was honoured to be asked to attend an event for Bradley Manning in central London, with Chase Madar, a US attorney, and the author of The Passion of Bradley Manning, and Ben Griffin, at which Julian Assange also spoke, via video link for the Ecuadorian Embassy. I spoke about the importance of the classified military files relating to the Guantánamo prisoners, on which I worked as a media partner with WikiLeaks during the release of the documents in April 2011, and I praised Bradley Manning for making them available, and helping to add to the weight of evidence that most of what constitutes the so-called evidence in Guantánamo is profoundly unreliable, produced in statements made by prisoners who were tortured, abused or bribed, and put together by analysts who were incompetent.

However, the description of Bradley Manning that stuck with me the most was Ben Griffin’s description of him as the greatest anti-war activist ever.

As Chris Hedges wrote, describing the significance of Bradley Manning’s actions:

This trial is not simply the prosecution of a 25-year-old soldier who had the temerity to report to the outside world the indiscriminate slaughter, war crimes, torture and abuse that are carried out by our government and our occupation forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is a concerted effort by the security and surveillance state to extinguish what is left of a free press, one that has the constitutional right to expose crimes by those in power. The lonely individuals who take personal risks so that the public can know the truth — the Daniel Ellsbergs, the Ron Ridenhours, the Deep Throats and the Bradley Mannings — are from now on to be charged with “aiding the enemy.” All those within the system who publicly reveal facts that challenge the official narrative will be imprisoned, as was John Kiriakou, the former CIA analyst who for exposing the U.S. government’s use of torture began serving a 30-month prison term the day Manning read his statement. There is a word for states that create these kinds of information vacuums: totalitarian.

Below are excerpts from the 70-minute statement that Bradley Manning made in a pre-trial hearing at Fort Meade on February 28, accepting responsibility for the leaks.

On “Collateral Murder,” the 2007 video from Iraq, Bradley was horrified by the callousness and blood lust of the US military personnel involved. As he explained:

The video depicted several individuals being engaged by an aerial weapons team. At first I did not consider the video very special, as I have viewed countless other “war porn”-type videos depicting combat. However, the recording and audio comments by the aerial weapons team and the second engagement in the video of an unarmed bongo truck troubled me. [...]

It was clear to me that the event happened because the aerial weapons team mistakenly identified Reuters employees as a potential threat and that the people in the bongo truck were merely attempting to assist the wounded. The people in the van were not a threat but merely “good Samaritans.” The most alarming aspect of the video to me, however, was the seemingly delightful blood-lust the Aerial Weapons Team seemed to have.

They dehumanized the individuals they were engaging and seemed to not value human life, and referred to them as, quote unquote, “dead bastards,” and congratulated each other on their ability to kill in large numbers. At one point in the video there is an individual on the ground attempting to crawl to safety. The individual is seriously wounded. Instead of calling for medical attention to the location, one of the aerial weapons team crew members verbally asks for the wounded person to pick up a weapon so that he can have a reason to engage. For me, this seemed similar to a child torturing ants with a magnifying glass.

While saddened by the Aerial Weapons Team crew’s lack of concern about human life, I was disturbed by the response of the discovery of injured children at the scene. In the video, you can see a bongo truck driving up to assist the wounded individual. In response the aerial weapons team crew assumes the individuals are a threat. They repeatedly request for authorization to fire on the bongo truck, and once granted, they engage the vehicle at least six times.

Shortly after the second engagement, a mechanized infantry unit arrives at the scene. Within minutes, the aerial weapons team crew learns that children were in the van. Despite the injuries the crew exhibits no remorse. Instead, they downplay the significance of their actions, saying, quote, “Well, it’s their fault for bringing their kids into a battle.”

On finding the Guantánamo files (the DABs, or “Detainee Assessment Briefs”), Bradley said:

The DABs were written in standard DoD memorandum format and addressed the commander of US SOUTHCOM. Each memorandum gave basic background information about detainees held at some point by Joint Task Force Guantánamo. I have always been interested in the issue of the moral efficacy of our actions surrounding Joint Task Force Guantánamo. On the one hand, I have always understood the need to detain and interrogate individuals who might wish to harm the United States and our allies, however, the more I became educated on the topic, it seemed that we found ourselves holding an increasing number of individuals indefinitely that we believed or knew to be innocent, low-level foot soldiers that did not have useful intelligence and would’ve been released if they were held in theater.

I also recall that in early 2009 the then newly elected president, Barack Obama, stated he would close Joint Task Force Guantanamo, and that the facility compromised our standing over all, and diminished our, quote unquote, “moral authority.” After familiarizing myself with the DABs, I agreed.

Reading through the Detainee Assessment Briefs, I noticed they were not analytical products. Instead they contained summaries of [unavailable] versions of interim intelligence reports that were old or unclassified. None of the DABs contained names of sources or quotes from tactical interrogation reports or TIRs. Since the DABs were being sent to the US SOUTHCOM commander, I assessed they were intended to provide general background information on each detainee — not a detailed assessment.

Bradley’s key statement on the Guantánamo files is when he says, “the more I became educated on the topic, it seemed that we found ourselves holding an increasing number of individuals indefinitely that we believed or knew to be innocent, low-level foot soldiers that did not have useful intelligence and would’ve been released if they were held in theatre.” This is absolutely the case, and I can only take exception to his belief that they were “not a detailed assessment.”

They were indeed only a round-up of the available information from a variety of military sources, but, crucially, they provide the names of the men making the statements about their fellow prisoners, which were not available previously, providing a compelling insight into the full range of unreliable witnesses, to the extent that pages and pages of information that, on the surface, might look acceptable, are revealed under scrutiny to be completely worthless.

My project to analyze all the files stalled about halfway through, when I ran out of funding, and was, to be honest, exhausted, but I fully intend to engage in further research in the near future, as the material will, I believe, be extremely useful for the 80 prisoners at (out of 166 in total) who have not already been cleared for release by an inter-agency task force that President Obama established when he took office in January 2009.

I believe that the information in the files will help to ascertain that, contrary to what the US government believes, there is very little reliable information that can be used to justify the detention of the 46 prisoners still in Guantánamo who were designated for indefinite detention without charge or trial in an executive order that President Obama issued two years ago.

Nor, for that matter, can the information relied upon by the US government justify, in general, the detention of the 34 other men who were recommended for trial by the inter-agency task force, established by the President, which also made the recommendations about the 46 others in a report in January 2010. Since then, the tattered credibility of the trials at Guantánamo — the military commissions — has been thoroughly undermined by Conservative judges in the court of appeals in Washington D.C., so that, with the exception of the seven men already charged, it is possible that none of the others will be charged, and their detention too will be supposedly justified on the basis of information that is, for the most part, equally unreliable.

As people around the world campaign for Bradley Manning on Saturday, I hope I will not be alone in realizing that his release of the files relating to the Guantánamo prisoners is not just something of historical significance, because the information in the files is still playing a part in the ongoing campaign to close Guantánamo.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 28, 2013

For My Guantánamo Work, I’ve Been Short-Listed for the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism

I’m delighted to report that, in recognition of my work on Guantánamo and the “war on terror” over the last seven years (including being the lead writer on the sections of a report on secret detention for the United Nations in 2010 dealing with US secret detention since 9/11, and being a media partner of WikiLeaks for the release of classified military files from Guantánamo in 2011), I’ve been short-listed for the prestigious Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism, dedicated to the memory of Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998), one of the great war correspondents of the 20th century.

I’m delighted to report that, in recognition of my work on Guantánamo and the “war on terror” over the last seven years (including being the lead writer on the sections of a report on secret detention for the United Nations in 2010 dealing with US secret detention since 9/11, and being a media partner of WikiLeaks for the release of classified military files from Guantánamo in 2011), I’ve been short-listed for the prestigious Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism, dedicated to the memory of Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998), one of the great war correspondents of the 20th century.

The prize was established in 1999, and previous winners include Nick Davies, Robert Fisk, Patrick Cockburn, Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, Dahr Jamail, Mohammed Omer, Ian Cobain, Julian Assange and Gareth Porter.

As noted by the Committee (James Fox, Jeremy Harding, Cynthia Kee, Alexander Matthews, Shirlee Matthews and John Pilger), the prize is “awarded to a journalist whose work has penetrated the established version of events and told an unpalatable truth, validated by powerful facts, that exposes establishment propaganda, or ‘official drivel’ as Martha Gellhorn called it.”

As Martha Gellhorn also noted, highlighting an essential truth about how people allow themselves to be manipulated — something that is, sadly, abundantly clear from the “war on terror” declared by the Bush administration after the 9/11 attacks, and the lies told about the prisoners in — “Gradually I came to realize that people will more readily swallow lies than truth, as if the taste of lies was homey, appetizing: a habit.”

The winner will be announced on June 19, and, to reiterate, I’m deeply honored to have been short-listed.

Below, to provide some context for the prize, is a video from 1983 of Martha Gellhorn interviewed by John Pilger:

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 27, 2013

Why We at “Close Guantánamo” Have Cautious Optimism Regarding President Obama’s Plans for the Prison

[image error]I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.