Jenni Fagan's Blog, page 5

October 27, 2016

The Filaments of Fiction: Jenni Fagan on A Clockwork Orange

Picture this — a 15 year-old girl is in a tiny bedroom. There are twelve other identical bedrooms outside her door. She angles a standard issue social work bed diagonally across her room to disrupt the aesthetic uniformity of this children’s care home. There is a stack of books in the corner. A lot of those books are on the occult or science. She is smoking. The window is open. The staff can be heard chatting downstairs. The kids in this unit do not use official titles for the ‘care workers’, they are just ‘the staff’ a collective presence that comes and goes. The kids do not go home at the end of each day. Especially not this one. The girl is wearing Doc Marten boots. She is reading A Clockwork Orange.

On the last few pages the girl finds her body colluding with the text. There is a low feeling of electricity coming off the page. Momentum gathers toward the part of A Clockwork Orange that is somehow the most shocking — the protagnist Alex — who has committed heinous violence and been dealt with in the most brutal and futuristic manner — is the exact same age as her.

The girl puts down the book.

She has been altered.

A Clockwork Orange attached itself to my fifteen-year old life and delivered a series of electronic volts.

I am that girl, who later grew up and became a published novelist and poet. It takes a lot to shock me in real life and also in literature. I have lived through so many extreme circumstances that I am extraordinarily hard to impress in that way. A Clockwork Orange attached itself to my fifteen-year old life and delivered a series of electronic volts not dissimilar to those experienced by Alex, when he goes through his rehabilitation process.

The first part of the book sees Alex as leader of a gang of droogs — teenage criminals. His cronies comprised of Dim, Pete and Georgie. They drink drug-laced milk in the Korova Milk bar and another establishment called the Duke of New York.

The droogs speak to each other in a slang language called nadsat. A Clockwork Orange‘s slang dialect steals elements of Russian and Cockney English. I loved the unfamiliarity of nadsat. As I began to read A Clockwork Orange I had the amazing realisation that I could understand everything these boys said in nadsat. It was my first experience of discovering dialogue that was not in straight English but could still be understood by anyone. As a young Scottish girl who was not taught how to write in Scottish dialect, or use the spellings of my own dyadic working-class tongue — this particular experience would prove pivotal when I sat down to write my first fiction novel some years later.

Alex defies convention at every turn. He listens to Classical music, loudly, a lot. He likes to read the Bible. He is an unlikeable protagonist who relishes the disgust he generates. His penchant for violence is underlined by an absolute lack of remorse. He is undaunted by State and society — he merely tolerates what he considers to be the idiocy of adults.

His rehabilitation process in prison is Ludovico’s technique and it is so successful that Alex is released from prison after two years. He can’t see violence anymore without becoming physically sick. He is immobilised by rehabilitive conditioning. He can’t listen to classical music anymore as he associates it with his prior violent history. He has been declawed and sent out into a world as a harmless and defenceless citizen.

Revenge is visited upon Alex by Dim and Billy boy who have become police officers. They beat him brutally. Alex tries to get help and comes across the husband of the woman who had died from injuries the droogs inflicted years earlier. The man is a political dissident. Alex goes through final stages of torment being used as a tool against the State and by them. Finally he wants to have a normal life with a wife and family.

I loathed Alex.

I was utterly compelled to read his story.

I found the black and white nature of Burgess’s approach to the moral nature of violent teenagers claustrophobic and repellent. The unrepentent portrayal of a young psychopath was also extraordinarily powerful.

I was a teenager who had experience of the world Burgess wrote about and I was still living in it when I read this book. I did not feel intimidated by Burgess’s vision. It irritated me. It frustrated me. It got under my skin. I was impressed.

A Clockwork Orange generated a multiplicity of responses in me as a reader. I left this novel expecting a higher standard both in my own writing, which I did every day even then and also in any dystopian books I would read in the future.

A Clockwork Orange marries its futuristic dystopian narrative with identifiable issues from modern society to devastating affect.

It was the first novel of its kind to affect my vision as a reader and more importantly for me, as a writer. When I wrote The Panopticon years later, it was a book that was still vaguely on my mind.

PIECE PUBLISHED in UNBOUND WORLDS – http://www.unboundworlds.com

October 16, 2016

Brooklyn Magazine

Jenni Fagan knows what it’s like to be an outsider. It’s a trait she shares with many of her characters, including the heroine of her 2013 debut, The Panopticon. That novel follows the prickly Anais Hendricks as she maneuvers the foster care system in the UK, a childhood reality Fagan also weathered. When the book opens, Anais has just arrived at a juvenile delinquent center for putting a cop in a coma—a crime she cannot remember committing. Voice-driven, acerbic, and sharp, the novel earned Fagan a coveted spot on Granta’s prestigious Best Young British Novelists list, along with powerhouses like Sarah Hall and Helen Oyeyemi.

While Fagan’s latest couldn’t be further from the all-seeing eye of The Panopticon, she says she was still very much thinking of fringe culture while writing The Sunlight Pilgrims. A gritty survival tale set in the not-too-distant-future, The Sunlight Pilgrims takes place in a caravan park in Northern Scotland. Thanks to melting sea ice, temperatures fall to inhospitable levels, and the residents of the caravan park are especially vulnerable.

As the days grow colder, newcomer Dylan, grieving the loss of his mother and grandmother, befriends Stella, a transgender teen, and her survivalist mother, Constance. All three characters must learn how to navigate challenging emotional landscapes, even as the physical world—portrayed as both beautiful and deadly—shifts under their feet. For a tale about the end of the world and the brutality of nature, The Sunlight Pilgrims is human, intimate, and weirdly hopeful.

Fighting the time difference between the U.S. and the UK, I spoke with Jenni via phone while still on my first cup of coffee (she was well into her afternoon). We discussed climate change, Brexit, the origins of Stella, and outsider modes of art.

Did you set out to tackle climate change in the novel, to make it part of the setting and the thrust of the story, or did it sneak up on you?

No. I didn’t want to write a climate change novel at all. I was thinking about light, the quality of light, and how we interact with light. I had had two quite close bereavements and a baby all in a short space of time. So I was thinking about light, and I was thinking about mortality, how we incorporate grief in our life. We look for light in darkness. We look for light in all things. So really that’s what I started out with.

I came back to Scotland from London, where I had been living for quite awhile. And I kept remembering these really extreme winters when I was a child—I lived in a caravan for quite awhile when I was a kid at one point—and I remembered having very extreme Scottish winters in rural areas. I moved back expecting to have one of these winters, and it never happened. I missed the last big winter here by one year. The year before I moved back, they had to get the Army out to clear the streets so people could get milk and bread and that sort of thing. And since I moved back there hasn’t been another extreme winter.

I was looking for an opportunity to inhabit these landscapes personally and artistically. Quite often the two things merged. If I wanted to write something about climate change, I’m far more likely to write an article or a thesis or a campaign. Certainly it’s not a subject that can be ignored or should be ignored, but it wasn’t the founding purpose of the book.

As the book began to progress, and I realized it was going to tap into these Ice Age conditions, I began to meet with meteorologists and research what was going on in the global community regarding climate change. I’m always intrigued by the way that modern life is designed to detract from the fact that we’re living on a planet, and our lives our very short. I really felt that when people are living to extremes, they can no longer afford to ignore that. So really, artistically, that was the thing that intrigued me most.

At least in the beginning of the novel, the bureaucracies of the village are still functioning, so we haven’t been thrown into complete chaos yet. There’s a sense of normalcy that helps ground the book in a recognizable reality. How did you strike a balance between the day-to-day and extraordinary in the book?

I was fully aware that I could have immersed myself in the Arctic chaos that is going to ensue right across Europe. The characters in this novel, they see parts of it, but they’re very removed from the cities, they’re very removed even from the village. They’re very much on the edge, and because they’ve always been on the edge, they’re probably better suited to just getting on with it. Certainly Constance, the mother, is a natural survivalist, and she doesn’t want to freak her child out. She doesn’t see that there’s anything to be gained in running around being dramatic about it, so she knuckles down and gets on with it.

People live through extreme circumstances all the time. And they don’t always go out and loot their neighbor’s house or shoot somebody or any of those things. But quite often people are just still doing life. They still have to eat, they still have to wash their clothes, they still have to look outside the window and think, “I wonder if I’ll make it to the end of this year.” At the end of the day, nobody really knows that. We all live with great uncertainties in our own lives and in the world. And that’s just become more extreme, I think, and more publicly discussed, over the last five years. That is one of the main questions of the book: how do you live your life well in uncertainty? How do you live well and stay true to your identity?

We do live on a planet, and the weather conditions that we’ve had over the last 10,000 years have been pretty unusual. Humans have enjoyed relative stability in some ways, and obviously each year we see more and more disasters happening. We live on a planet, and planets are massively changeable. Our impact on them is huge, and we’re collectively getting to the point where we can’t ignore that anymore. We shouldn’t have been ignoring that in the first place.

There’s something really hopeful about the way characters discuss the possibility of survival, right up until the end of the book.

They choose to accept what’s happening. If they were different kinds of people, if they had different philosophies, they might fight it more. They’re not so shocked that [death] would happen. And being in a position of acceptance doesn’t mean you’re without hope. People have survived Ice Age conditions. They are all still hoping they will get through it. I often think of winter as the other main character in this book. Dylan’s completely besotted with the landscape. And it’s beautiful, stunning. But deadly, utterly deadly.

When your book published in America, Brexit had just happened. Did the politics in the book and the politics in real life resonate for you at all?

Of course Brexit happened here long after the book came out in the UK, so it didn’t feel as connected. We’re seeing a huge flux in populations, now more than ever, because of war or famine or climate change. The book has an awareness of people being in transition—and you can’t not engage with [that reality] as an artist or a writer. The question of what happens when people are denied safety or denied basic human rights is hugely important. These things always feed into my writing. I think writers, musicians, and artists are always filtering politics through basic, staple emotions. Art and literature, in particular, are a place to have these conversations. There’s something about fiction, about the imagination having free reign that isn’t afforded in real life, that makes this possible.

I was interested to learn that you’re both a poet and a novelist. Do these modes of writing inform one another, or are they quite separate?

They definitely inform one another. I recently published a book of poems, The Dead Queen of Bohemia. It’s 120 poems collected over time. I find when I’m writing a novel, I have to curb the poetry, I have to strip the words back. I write, as many people do, in a sort of stream of consciousness. I touch type, so it’s really just pure brain to the page. The image [in Sunlight Pilgrims] of “a woman polishes the moon” I lifted from a poem. Sometimes it’s a line, a theme, or imagery from my poetry that becomes a whole novel.

I don’t believe in literary monogamy. Every time I try out a new form, I gain a skillset to take back to other forms. I was a playwright for quite a long time, and it helped me learn dialogue. Now when I read a novel written by a playwright, I can always tell. There’s a stripped back quality, allowing yourself to be avant garde, to not be connected to traditional narrative forms. Every page in a play, every scene, has to be as clear as the others. When you’re writing a novel that’s 80,000 words you can’t just waffle for 40,000 of them.

So much of how you handle writing Stella’s transition is subtle and affirmative. Her narrative POV always uses gender terms like she/her. I even think about the first time Dylan sees Stella—she reads as female to him. I found that incredibly moving. How did you develop Stella’s character? What was it about the story of transitioning—or the contrast between a global change and a very personal one—that captivated you?

No, I don’t think like that. Stella just turned up on her bike, stripy tights, glittery nails, and she never stopped moving. She’s a character who’s had to fight for her own identity. She lives in fear in a small community. I grew up in care, and I identified as a child from care before I identified as myself because that’s how other people saw me. So that was my point of contact with her.

When I was younger I played in punk and grunge bands, which had a large LGBT community, so it wasn’t unfamiliar. Still, I did a lot of research because I wanted to make sure I got it right. I sent my manuscript to the writer Kate Bornstein, who edited Gender Outlaws, and I met with trans writers. And they were all like, “No, no, you’ve found her!” Ideas about gender are important to everyone; we’re all being forced into gender normative roles. But the thing I love about Stella is that it doesn’t define her. It’s not all of who she is.

In fact I was a bit hesitant to write her because of the last book. I thought, “Oh! Isn’t this a bit too close?” but I loved Stella’s relationship with Dylan. Both characters have been brought up by unconventional mothers. Stella, in her way, wants to rebel against her survivalist mother. She wants to get married and live in a house of bricks and be liked by other people. Constance doesn’t give much of a shit whether other people like her or not. When Dylan and Stella meet each other, Stella asks, “What about your dad?” and Dylan says, “My mum didn’t catch his name.” They both have to lay out their identities after being raised by such strong, unconventional women.

I was thinking quite a lot about the overlap between Stella and Anais, from your first novel, The Panopticon. They’re both spiky, young female narrators. What is it about the lives of young women who have been pushed to the fringes that captivates you? Is this territory you’ll return to?

I’ve really been writing the books I’ve wanted to read. I kept seeing fifteenyear-old girls in books who wore sparkly clothes and drank shandy and thought they didn’t resemble any of the girls I knew, or the women I’m friends with now. And I suppose in that sense I think like Patti Smith. She said the females were her muse.

All writers writing from the periphery are pointing toward the center. Because I grew up in the periphery, I think it makes you more observant of what’s going on in the culture. In my twenties and thirties, all the most vital and vibrant stories came from the periphery. Art house cinema, punk, New Wave, it all came from the fringes. I did a lot of research about the “Self” and “the Other” while writing this novel. In a sense, the periphery is a mirror, showing the center what it is. That’s why we’re artists, we’re responding to the center.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on two novels at the moment. Novel Three and Novel Four take place over 110 years, and in some ways Novel Four is really the last chapter of Novel Three. But you can read them separately or out of order. I’m trying to write the Great Edinburgh Novel. It’s a huge span of time to work in, and I hate historical fiction that doesn’t make each historical part feel vital to itself. We’re not the ones who invented sex or drugs; this stuff has been around for time immemorial. In fact, the third book is some of my darkest and most graphic, most sexual work. The character who opens that novel is also related to Gunn MacRae [from The Sunlight Pilgrims], so there are these slight nods to the other books.

I can’t hassle poems, I don’t mess with them. They might take a week or ten minutes to write, but great poems come out almost whole. With a novel, I’m riffing on something for 80 pages. I have a big space to look at a problem from all these different angles. I think a lot about when I used to make music. You would go into these dirty little rehearsal rooms and play for ten hours, twelve hours, and you keep doing it and keep doing it and that hopefully produces something. I try not to hold [a novel] too close. If you trust that artistic part of your brain, it’ll bring you the good shit.

Interview by Kirsten Evans at Brooklyn Magazine

August 16, 2016

Read It Forward

Five Authors Jenni Fagan Would Invite to a Dinner Party

The author of The Sunlight Pilgrims picks her dream dinner dates.

First published by Read It Forward

BY JENNI FAGAN • 4 DAYS AGO

If you could invite five famous authors—dead or living—to dinner, who would you choose, and what would you serve? Today on Read it Forward, novelist Jenni Fagan hosts the dinner party of her dreams. Salut!

Gertrude Stein

I wish I’d spent time at Gertrude Stein’s extraordinary salon in Paris. She is a big influence on me. I would want to hear stories about all the painters she knew, how they arrived at automatism, what were the most banal and ordinary things she can recall of the surrealists, and who was the bravest? Also, I’d ask her if she ever used her wife Alice B. Toklas’s cookbook.

Nick Cave

I am a fan of Nick’s prose and I truly adore him as a musician. A dinner party made solely of writers would be dreadful, so we need at least one person who can get on the piano, involve us all in a sing-a-long, and have us waltzing on the patio before dinner. And is it just me, or would he have the best jokes and stories? I’d want to know how he found all those eras and musicians, from no-wave and punk, to garage rock and lo-fi. And if he played The Ship Song at the end of the evening, I could, in all honesty, die happy.

Leonora Carrington

I love Leonora for everything really—her painting, her prose, her politics, her astonishing life. I also love her quotes about writing: “The task of the right eye is to peer through the telescope, while the left eye peers into the microscope,” or another favorite, “People under seventy and over seven are unreliable if they are not cats.”

Reinaldo Arenas

Reinaldo Arenas once said, “There’s just one place to live—the impossible.” He also said, “I have always considered it despicable to grovel for your life as if life were a favor. If you cannot live the way you want, there is no point in living.” I would want to know everything; about his years incarcerated for being a gay man in Cuba under Castro’s regime; his move to New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen and his departure from Cuba on a boat for criminals, disabled or gay citizens; his lovers, his mother, his relationship to landscapes. His uprootedness and dislocation speak to me profoundly.

Helen Oyeyemi

I happen to know that Helen Oyeyemi is not only one of the best writers of our time but also, the most charming dinner guest. The first time we met she told me about a clock in Prague that can tell the time on the moon, how she had grown obsessed with keys and also what was great and good in Korean horror movies. I’d polish my teapots and serve an array of teas in the early morning before they all went home, which I know she would appreciate.

~Menu~

Pre-dinner drink:

The Paloma—a Mexican cocktail: ingredients—1/4 mezcal, 1/4 fresh grapefruit juice, wedge of lime & 1/4 soda, kosher salt, crushed ice. Run lime around the rim of the glass, dip in salt, mix your ingredients, add ice.

I am sure it is best to start a dinner party with drinks and dancing so you are more ready to sit, chat, eat later in the evening. Leonora Carrington spent most of her adult life in Mexico City, so I am hoping she might like this spirited start to the evening.

Starter:

In honor of Reinaldo Arenas, I would make Cassava bread, made from cassava flour (great if you are Paleo), and serve with tapenade on the side and a piri piri sauce for dipping.

Selection of Spanish Tapas (vegetarian for Nick Cave)—black olives, Ajillo mushrooms, Habas ala Catalana (smothered broad beans with sausage), Espinacas Con Garbanzos (spinach and chickpeas), Alubias Verdes con Ajo (green beans with garlic).

These would be small dishes that are easy to pick at—just to take the edge off our Palomas and prepare us for the main course.

I’d also hope Reinaldo might bring a few nice Cuban cigars for later, I’m sure he’d appreciate a smoke on the patio late at night, as would Gertrude for that matter.

Main:

I’d like to cook a meal that is easy to serve and enjoy—so we can focus on chatting. I’d make paella, the first would be a vegetarian version and for the second, I’d add seafood and chorizo.

Ingredients: Fresh saffron from the market in Istanbul. Garlic, paprika, cayenne pepper, mushroom, peppers, chorizo, olive oil, scallops, black Irish mussels, free-range chicken, onion, tomatoes, peas, calamari, Calasparra paella rice.

Dessert:

This would not happen until much later. I have a feeling that after the last two courses, we’d all wander down a dark country road, have a look at the Milky Way in a starlit sky, have a few games of pool, or darts at the local pub—then head back to play music and dance. The garden would be lit by fireflies in jars. We’d have a selection of the finest Parisian patisserie cakes and I’d ask Gertrude about her favorite baker along the rue de Fleurus. I bet you she’d say Picasso had a sweet tooth.

And when all the food has been eaten:

Helen Oyeyemi lives in Prague and I’m sure she’d oblige with a bottle of plum brandy (Slivovitz—she knows where to get the good stuff) or perhaps a small absinthe, especially if we were on the cusp of an aurora that night, which I’d hope we would be. She’d be setting up a little outdoor cinema on the lawn, talking Nick Cave through the greatest Korean horror movies of all time, the porch would be wide and the weather mild, perhaps a stream nearby and a swing on a tall tree in the garden. I imagine Gertrude having a snooze on the porch under a blanket. Reinaldo telling me stories about the Cuban revolution and the grit of Hell’s Kitchen, and how his first novel was smuggled out of prison and over to Paris, the only place he could publish it at the time. Leonora would reminisce about founding the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mexico, her love affair with Max Ernst, running away from an asylum and creating a novel about her psychotic experience. We would discuss the extraordinary way she paints. Psychic freedom. Automatism. Surrealism. Keys. Clarity. Mirrors. We would chat all night in the garden where a rose, is a rose, is a rose.

Featured Image: Rawpixel/Shutterstock.com

July 17, 2016

The New York Times Book Review

BOOK REVIEW | FICTION-FRONT COVER of THE NEW YORK TIMES

A New Novel Envisions a Very Cold Environmental Future, Starting Now

By MARISA SILVER JULY 15, 2016

THE SUNLIGHT PILGRIMS

By Jenni Fagan

272 pp. Hogarth. $26.

As carbon dioxide levels rise, as humans create more and newer justifications for institutionalized murder and as lethal diseases ravage unsuspecting populations, writers respond. They bring us novels of the post-apocalypse — philosophical explorations of what the world might look like when the fraying center finally shears. Whether the approaches are starkly realistic or fancifully speculative, these visions generally posit an end-time far enough into an unrecognizable future that we can maintain our illusions of safety from the comfort of our reading chairs.

Jenni Fagan, the fierce and cleareyed Scottish writer, will have none of that. In her new novel, “The Sunlight Pilgrims,” she is committed to disrupting our ease by setting her story of impending cataclysm at a moment unnervingly near at hand. Fagan’s novel is set in 2020, and the world is familiar in every way but for one menacing difference: It is very, very cold.

The polar ice caps are melting, and the seas are rising. The mercury, as the story opens, is set at minus 6 degrees — colder than most of us regularly experience, but not unimaginable. And it is not so for the three characters who are the novel’s focus: Dylan, an unusually tall man who, at age 38, is grieving the back-to-back deaths of his mother and grandmother; Constance, a self-reliant survivalist; and her daughter, 12-year-old Stella, a transgender girl who is on the cusp of a puberty that, unless she is able to begin a course of hormone treatments, will deny her the external appearance that matches the girl she knows herself to be. Mother and daughter are part of an off-the-grid community of caravan dwellers who live just outside the fictional town of Clachan Fells in northern Scotland. Constance relishes her independence as well as her distance from the townspeople, who judge her harshly for carrying on open affairs with two men simultaneously, one of whom is Stella’s married father. Dylan, a Londoner, is an “incomer,” newly arrived having inherited a caravan from his mother. Cut off from any future he ever imagined and lacking in basic survival skills — he greets the deep freeze in a pair of thin-soled Chelsea boots — Dylan strikes up a friendship with Stella and Constance just as what is predicted to be the worst winter in 200 years descends over much of the planet.

Fagan’s novel balances the oncoming climate disaster with the human-scale stories of these characters, focusing especially on Stella, whose feelings about her sexual identity are refreshingly resolute. Her confidence about her girlhood, and the pleasure she takes in it, as well as the way she stands her ground when dealing with the hurtful rejection of schoolyard bullies, reveal that she possesses a kind of resilience that may serve her well in uncertain times. She is supported by her mother, although not by her birth father, a fact that causes her to hope for the romance between Constance and Dylan she senses brewing.

Stella’s intrepid and sometimes dangerous attempts at self-care, and her coming-of-age under the pressure of societal disapproval and global threat, are the emotional anchors of the narrative. The interior lives of the adults in the novel are not quite as precisely drawn. We don’t learn much more about Constance than that she is an adept survivor who keeps her emotional entanglements at a safe distance. Dylan is a somewhat unformed man whose lack of direction and self-knowledge might be ascribed to the fact that his lineage has been kept from him, information that he will uncover during the course of the novel and that he fears will threaten his relationship with Constance and Stella. This conventional narrative ruse — the unearthed secret — is not wholly persuasive in a book that admirably avoids melodrama, especially since the revelation does not have the weight of meaningful consequence. What does matter, and something Fagan handles with deceptively effortless prose, is the way in which ordinary, even banal, life dramas unfold while the existential noose is tightening. The girl’s sense of the dislocation is tender. “Her voice is sending her odd notes. Her body is becoming a strange instrument,” Fagan writes evocatively, and then, easing from the distanced poetry of the writer’s omniscience into the mind of this witty child, “Any day now a tiny man is going to set up a loudspeaker in her throat and his voice will make declarations in a baritone and everyone will think it is her speaking, but it won’t be.”

The mercury plummets, ultimately reaching an unfathomable and unsurvivable minus 56 degrees. As the days grow short and most of life must be spent inside the confines of a trailer, the claustrophobia Stella feels inside a body that might soon betray her is mirrored by what is happening in the world. When she takes an ill-advised bike ride into the freezing weather, we feel not only her physical desire to break out of her trailer home but also her desperation to escape the gender she was born into. Fagan joyfully summons the sheer jubilance of the girl’s physical power as well as her fear when she realizes she’s out of her depth in the freeze. The evocation of that maturational tipping point where wisdom trumps desire is one of the novel’s wrenching explorations. There is so much for this young girl to lose. That she receives news of frozen bodies and devouring sinkholes, of food shortages and economic collapse from the internet makes her isolation that much more devastating. A young Italian transgendered man who is Stella’s online consigliere suddenly disappears from the web, and we, like Stella, can only wonder if he has fallen victim to the freeze.

“The Sunlight Pilgrims” is a stylistically quieter novel than Fagan’s bravura debut, “The Panopticon” — a fiery and voice-driven effort that landed her on Granta’s 2013 list of the best British novelists under 40 years old — but it is no less critical in its portrayal of marginalized people under the pressure of society’s norms. When Stella and her mother visit a doctor in hopes of getting Stella started on hormone therapy, the unhelpful man suggests antidepressants. At a community meeting, the nuns who run Stella’s school, and who do nothing to support or accommodate the girl’s gender transition, greet the oncoming freeze with educational leaflets and announcements about community preparedness plans including “ideas on how to insulate and heat your homes,” information that will be useless when the temperature drops and resources become scarce. At the meeting’s closing prayer, “Stella gazes around at the bended heads and Mother Superior is looking at her . . . and there is a faint distaste in her eyes.” It is easy to imagine that this young, marginalized girl and her anti-authoritarian mother will get no special help from their local church, insulation or otherwise. The difference in the argument from Fagan’s first novel to her second is that with the world tipping into disaster, intolerance will seem like a petty thing. No one, not even those who hew to ideas of perceived “normalcy,” will be spared. In this way, the satire in this novel is even sharper. A church that largely recoils from embracing difference can do nothing when it comes to protecting the earth from human abuses and vanities.

Fagan is a poet as well as a novelist, and many of her images of this unbidden winter are shot through with lyric beauty. Early on, we are told that in this worst of winters “icicles will grow to the size of narwhal tusks or the long bony finger of winter herself.” Later, when the threesome venture out of the caravan to witness an iceberg’s arrival, they observe “all those peaked figures of ice, like all of their ancestors have been caught by the elements on the long walk home, their souls captured by ice and snow, and below them the North Sea cracks and groans as ice floes creak and collide.” Strange beauty can be found in destruction, and Fagan is fearless and wise to allow her characters to be as entranced by nature’s awesome power as they are terrified of it. The mythic reach of such imagery mirrors the way Fagan overlays elements of the tribal onto the quotidian. The novel’s three central characters are as much recognizable humans as they are visitations from a folk narrative. Dylan is an orphaned giant whose mother, to obscure his troubling lineage, told him he was the product of a fallen angel and a mortal woman. To ward off the worst of the chill, Constance frequently dons the pelt and preserved head of a wolf, so at times she seems a strange hybrid. Stella is a double, both a boy and a girl. The local lore about the sunlight pilgrims of the novel’s title tells of a race who drink light to live through the darkest times. But Fagan does not use metaphor as poetic immunity for her characters or her readers. The novel leaves them — and us — in a deeply troubling and unresolved moment. The world looks like a place of our darkest imagination, but it is all too real.

July 15, 2016

The Sunlight Pilgrims

The Sunlight Pilgrims has been published in the UK by William Heinemann, Random House. It is due for US publication with Hogarth on the 19th July.

This is me with Mariella Frostrup & Antonia Honeywell on BBC Radio 4 Open Book.

Signing first editions at York Hall.

Drawing below by an artist with The Skinny in Scotland, I really liked it.

My second novel has been a thing I’ve held close for quite some time. I tried not to be intimidated by all the positive things that happened when William Heinemann published The Panopticon. In the end it freaked me out. Every new piece of work does this though. It just so happens I am in love with words — it won’t change now, I’ll take the discomfort for the practise of it, the feel of it, the sound and sensation and strange of it.

I had to strip this novel back halfway through the process and go back to working with my gut instincts and trusting that sound of tip-tap, tip-tap.

I spoke to a writer I really admire a few weeks ago. She was writing a new novel and despite being so accomplished and a stunning writer — she asked me to send her luck for the fear space.

I think it’s meant to be there!

Writers aren’t meant to exist in a hazy rainbow of happy-cyclonics. I will publish the first few pages of The Sunlight Pilgrims on here quite soon perhaps. I have loads more news but I have as ever, been moving, living, doing too much. I am hoping my eternal transience may halt for a while now as I am already writing the next two novels and settling in for the dark nights and early mornings.

In the meantime I’ll raise a glass this weekend seeing as The Sunlight Pilgrims is about to cross the water and be published in the US. Stella, Constance, Dylan, Gunn, Vivienne, Barnacle — seven snowy mountains, frost flowers, gin stills, icicles as long as narwhal tusks, the long bony finger of winter herself, drinking light, to overly tattooed nephilim, BMX riding trans goth girls, and women who polish the moon — here’s looking at you!

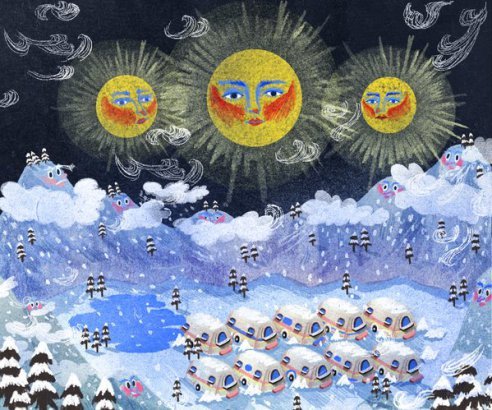

There were three suns in the sky and it was the last day of Autumn, perhaps forever.

Developing Character (Foyle’s website)

So you are sitting somewhere and a character turns up. They sidle onto the tube. Or they sit down next to you in a bar. You think they’re going to read a book, or order a gin and tonic but they start chugging on a shisha, or texting in Latin, or sliding a flower over to you that you strongly suspect is stolen.

So, you are lying in bed and a character materialises making you get up and turn your laptop on. It’s begun. The years with this character. It’s awful. They’ll turn up any time they want. You better settle in and hope they don’t have any really, really irritating habits. You are going to know them like all the other people you see every day. Best get used to it.

In the kitchen in the morning you are trying to put a washing on, when you realise the thing that has been nagging at you about your character all night is the fact that they can’t see the colour blue without wanting to visit their best friends grave. So there your clothes sit, on the floor, the washing machine door open, while you go and write it down.

Some people have others to do their washing. Real writers do their own. I might get that on a sticker and slap it on the washing machine door.

Characters rarely arrive fully formed. It takes time to work out who they really are. It’s like getting to know a new friend or lover, or becoming a parent. All the experiences you share allow you to get to know someone and it is no different for characters in novels. By putting your character in different situations they reveal new things about themselves.

Be careful to not make your characters just an extension of yourself unless you are doing so deliberately. They need their own political beliefs, quirks, taste in music, likes, dislikes, memories, future goals.

Sometimes you need to let a character be more elusive. Perhaps they are only going to create a particular atmosphere when they enter a page. If your character stays resolutely beige or never develops, it’s okay to drop them off a cliff, with a parachute, saying — belongs elsewhere, do not return to owner.

Your character might change sex, name, hair colour, they might have an affair with a piccolo player in Honolulu, they could have a child growing up in Tipperary. If you act like you know everything about them, they’ll never bring you anything new. When you let them bring you new things, they’ll be much more interesting.

There are lots of tricks people use to develop character. They might write a questionnaire asking their character what their earliest memory is, or what they are afraid of, or why they have a scar on their knee, or who was the first person they kissed. These details may never end up in the story but they will help the writer a lot.

Characters need flaws. They must be in a process of becoming or even a process of never becoming. If your character starts out whole and complete then where is the space for them to grow or change? What’s the point in hanging out with them? People change and so do characters, each day that you write them. Eventually you can begin to imagine what they would think of things in your real life. That can be a little freaky. I had a character who was prominent in early drafts of a novel but by the end he was peripheral. I sat on the tube after deciding to cut most of his chapters and I could see him getting on the tube, sitting down, shaking his head sadly at me.

I mean I couldn’t actually see him!

I could see him the way I do in the books and it gets real enough for them to feel pretty true, especially when you are hanging out with them for five years in an attic.

It’s important to not always just write likeable characters, or even familiar ones. Writing furious, anti-social, frustrated, awkward, real characters is exhilarating. Writing someone who is polite all the time and just wants to be liked isn’t so interesting.

It is the space where imagination and character meet that creates memorable identities. Allow your characters to surprise you. You might have wanted to write one that only ate spaghetti and slept in a round bed but if it turns out they live in a hut on stilts in the forest where bison run underneath then go with it. You might find out they play the mouth organ and they once saved a horse from drowning. They might make you cry. Or, for the rest of your life you will have an image of them holding out their hand, helping someone off the train tracks. Let them be real. Let them be true. Stop trying to make them say things you want to say. Go out and say the things you want to say and let them say things you never knew they were going to say. If you are surprised, the reader will be too.

Some people use their characters as puppets, you can see the author pulling the strings all the way through, it’s hard to make a story feel natural when you can see the strings being pulled to create an effect or serve a purpose, that’s not my favourite kind of writing.

Writing a new character is like going on a first date. You might think this person is really chilled out then you get in a car and they’re a road rage maniac, who knew until you clicked in your seatbelt and sped off through the city at night!

Writing In Different Forms

I began writing poetry when I was seven years-old; this was followed by diaries and short stories. In my teenage years I added song lyrics and short scripts. I won a place as the youngest person on a Scottish Screen film writing retreat and wrote my first short films. I felt my skills in dialogue were a little weak so I decided to write a play for a competition I heard on the radio. I won it and spent three years writing plays.

I won an interview with a well-respected theatre company in London to write a play/film. They said my play was completely unique and distinctive in voice compared to every other one submitted however they had been arguing all morning about whether I was a playwright or a novelist. On the train home I watched the landscape whizz by and admitted to myself that I had been accruing skills so I could write novels. I quit writing plays that day.

Writing is the only artistic medium that takes place entirely in the writer’s and reader’s head. We see plays or films, listen to songs, go to art exhibitions. Novels, stories, poems take place wholly inside a person. They bring their own memories and emotions to the experience so they can never be read entirely the same way twice. I find this fascinating.

In poetry I allow discord in syntax, I go left ten times in a row then drop four floors just to get a better view. Only when the poem demands to be written do I put the words down.

Poems are a pure form. I don’t go after a poem, club it over the head and make it work, I don’t even look it straight in the eye. It’s also the only medium I always write by hand. Sometimes it feels like learning to walk on snow without leaving a footprint, impossible but somehow poems can do that, the best ones reconnect me to life and the world in a vital way.

With novels I sit down day after day and work on them. I work when it’s raining, when I’m ill, when it’s sunny, when I should be elsewhere, or when I want to do anything else but type. I turn up to write when I don’t know what is happening, when I am freaked out, when I’m tired, or happy, or lonely, or sad. Whatever else is going on in my life I will sit down each day and work on that novel. Each novel can take years. I might rewrite the opening literally a hundred times. A novel needs time to become clear, to grow into itself, to feel real.

I am writing the screenplay adaptation of my debut novel. I work closely with Sixteen Films who are making the film. We have long meetings in a little attic room in Soho where each line and every piece of dialogue or description is taken apart by a small core of people. We rigorously argue, debate, or discuss each line or action. I have really enjoyed testing the boundaries of adaptation and as the only screenwriter working on it I’ve learnt so much. I was also able to draw upon my earlier experiences in screenwriting and playwriting and that helped a lot.

Flash fiction is the poetry of the prose world, it is so generous and precise. I experiment with POV, tense, character, voice or subvert all my original intentions to really try out new ideas and skills.

Prose and poetry are the forms I have been writing for most of my life and I am still really excited by them. I will gladly commit three or four years to a new novel if it needs it. I am about to write one that will take at least three years as it is a vast, ambitious book. I have so much research to do and I love that part of the process, to meet interesting people and get my geek on.

When you edit, put your ego aside and be as critical as you can be, don’t write the life out of something but don’t indulge yourself with over attachment. Just because you like something isn’t enough reason to keep it. Every word has to serve the novel or poem or screenplay and if it doesn’t then cut it out, pin it up somewhere, and use it for something else later.

All truly great writing comes from a place of truth. If it is authentic then someone else will connect to it. If it is superficial, no matter how pretty the prose is, or how clever the poem is, it won’t get anyone else in the gut or heart so it won’t stay with them.

You have to trust your instincts and be respectful of your imagination — give it free reign, don’t limit yourself. If it is scaring you then write it, if you are daunted then you absolutely have to try it, if you are struggling then you might just be writing the piece that will elevate your work to the next level.

I can’t do monogamy with words. Each form gives me something different, they strengthen the others and I never get bored.

For the real writer there is no full stop. Be truthful, take risks, challenge yourself.

First featured on Waterstones Blog.

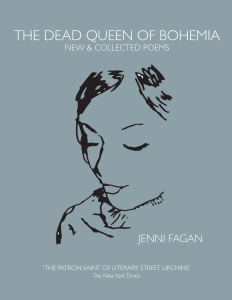

The Dead Queen of Bohemia (New & Collected Poems)

The Dead Queen of Bohemia (New & Collected Poems) has been published by Polygon, Birlinn Ltd. It features 120 poems and goes all the way back to the early years of Urchin Belle & The Dead Queen of Bohemia (published by Blackheath Books in Ltd. edition – you lucky ducks if you have one) and now encompassing over 65 new poems as well. It has been emotional, to put them all together and take them out into the world but I love the book and really love the production values. I have effectively drawn a line under the last few decades of poetry and I am starting over with a new body of work now. I was lucky to get drawings by Nathan Thomas Jones on the front cover and in some of the illustrations inside as well. I’ll write more on the poetry later, the picture above is of myself and Nathan at the York Hall launch in East London. York Hall is an amazing old boxing club with stunning art deco features. I read to a beautiful crowd, they roared, they drank, they were present, my brilliant publisher from William Heinemann was there alongside newer film acquaintances, it was a great moment to remember, Jx

October 27, 2015

Queen Bee of Tuscany

Writer Jenni Fagan, Portobello.

I had my portrait taken by a wonderful photographer called Angela Catlin. She is a fascinating person to chat to and the first time she came out I ended up in the sea, talking about a lot of stuff and not focusing much on the job at hand. Thankfully she popped out to see me again just after I had painted my wee beach house (still here for now) the living-room is a beautiful shade of french turquoise by Craig & Rose 1929. It just looks blue to me. The pictures behind me in the portrait are some of my favourites all grouped together. The sun was given to me by an artist in Berlin, where I was working when I was nineteen. We drove to a party listening to Rammstein (with eight others in very fast car on the u-bahn) I flicked a cigarette out the window, it came back in, my dress caught fire, they all thought it most amusing. The artist was called Conrad Andreas and he did a portrait of me in ink on a piece of lined paper as well, I have another print of his in the hall. The one above that is by Jose Arroyo, a US based writer and artist. There’s artwork from my wee boy. Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, a few of mine, including my favourite oil painting, I called it Write Like The Green Man as it encapsulated my approach to words and art. A great picture sent to me by the writer Joanna Walsh, I love the colours and words. I also framed my front cover of The New York Times article on The Panopticon, it is a classic front newspaper image, the small articles in the top hand corner read: The Girl Who Loved Camellias, The Astronauts Wives Club & Queen Bee of Tuscany. I have not really blogged for two years so I guess, with this here blog I am back, throwing down the satin gloves (not wore those for years) dusting off the spiderwebs, laying down the novel I just completed (The Sunlight Pilgrims), my New & Collected poems (The Dead Queen of Bohemia), and the film script for The Panopticon. It has been a busy few years of writing, knocking down walls, building fires on the beach, railing against that which must be challenged, trying, thinking, drinking tea, working, working, after that working a little more. I will be out doing lots of readings for my new novel and collected poems next year, I am looking forward to it. I am very quietly about to kick into novel 3, which I have been waiting on beginning for ages. There is another book on the go so I am not wasting the word hours, whenever I can fit them in. Will post more regularly again from now on. To check out Angela Catlin’s work take a look on my artists tab. Salut, salut, Jx

September 10, 2014

The New York Times

THE NEW YORK TIMES

(Front Page of Literary Supplement)

SURVEILLANCE STATE

‘The Panopticon,’ by Jenni Fagan

By TOM SHONE

Published: July 18, 2013

“I’m a bit unconvinced by reality,” says Anais Hendricks, the heroine of Jenni Fagan’s debut novel, “The Panopticon.” “It’s fundamentally lacking in something, and nobody seems bothered.” When we first meet Anais she is handcuffed in the back of a police car, her school uniform covered in blood, on her way to an institution for young offenders. She has no family, and has never seen so much as a photograph of any relatives. Her hobbies include joy riding, tripping on school days, painting CCTV cameras fluorescent pink and hand-delivering the lights from police cars, covered with glitter, to the desk of her local constabulary. Now 15, she still feels “2 years old and ready tae bite.” She is, in summary, “totally and utterly” messed up — “but I like pillbox hats.” She is also the best reason to pick up “The Panopticon,” Fagan’s pugnacious, snub-nosed paean to the highs and lows of juvenile delinquency. A student of Andrew Motion’s with several books of poetry to her name (a name that calls to mind the patron saint of literary street urchins), Fagan has given us one of the most spirited heroines to cuss, kiss, bite and generally break the nose of the English novel in many a moon.

The novel takes its title from the imposing rehab facility, located deep in a forest, that waits for Anais at the end of that car ride: four floors high, in the shape of a C, and in the center a hidden core that looks out, through one-way glass, onto every cell, every landing, every bathroom. Students of 18th-century English penology will instantly recognize the reformer Jeremy Bentham’s infamous plans for an omniscient prison, never built but later turned by the French philosopher Michel Foucault into a metaphor for the oppressive gaze of late capitalism. Students of 21st-century reality television will, on the other hand, instantly recognize the layout from the program “Big Brother,” in which a bunch of undesirables argue, in close quarters, over who redecorated the living room lampshade with a pair of underpants.

Where does Fagan’s structure rest on the Bentham-to-“Big Brother” scale? Somewhere in the middle. The inmates are locked up at night, but during the day are free to roam a lounge area, dining space and game room, all painted magnolia by well-meaning staff members who say things like “we practice a holistic approach tae client care at the Panopticon.” Winston Smith never had it so good. Anais lands there after she’s suspected of putting a policewoman into a coma, a crime for which she is regularly hauled into the interrogation room — but she cannot remember anything, having been on the tail-end of a four-day ketamine bender at the time. “I didnae tell the polis that,” she confides. She also does not tell them she was so wrecked on drugs at the time, “I couldnae even mind my own name.”

She is soon bonding with her fellow inmates, swapping stories and swinging joints attached to shoelaces between the cells after lights out. There’s the sicko who raped a dog, the boy who burned down the special-needs school where his foster mother taught. “We send e-mails, start legends — create myths,” she says. “It’s the same in the nick or the nuthouse: notoriety is respect.” What we have here is a fine example of Caledonian grunge, wherein writers north of the River Tweed grab the English language by the lapels, dunk it in the gutter and kick it into filthy, idiomatic life, thus leaving terrified book reviewers with no option but to find them “gritty” or “authentic.”

I have no way of knowing if the acid trip described here — which starts on the walk to school, then lurches sideways to a tower block for another drug run before concluding with a police bust — is authentic, having spent most of my school years protecting my privates from oncoming soccer balls, but there is no resisting the tidal rollout of Fagan’s imagery. Her prose beats behind your eyelids, the flow of images widening to a glittering delta whenever Anais approaches the vexed issue of her origins: “Born in the bushes by a motorway. Born in a VW with its doors open to the sea. Born in Harvey Nichols between the fur coats and the perfume, aghast store staff faint. . . . Born in an igloo. Born in a castle. Born in a tepee while the moon rises and a midsummer powwow pounds the ground outside.”

Solving this mystery — cracking Anais open — soon supplants the cop-in-a-coma as the book’s main narrative focus, as is only right, since “The Panopticon” is primarily, and triumphantly, a voice-driven novel.

Fagan’s prose rhythm and use of the demotic may owe something to Irvine Welsh, but there is a poet’s precision to some of the novel’s more plumed excursions. I, for one, was as grateful for those fur coats and that perfume as I was for the acid trips and dog rapes, the school of Welsh having long ago seized up, sclerotically, with its own druggie braggadocio. “Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face,” Updike said. Reading Welsh’s most recent work, you sense a writer trying, but unable, to break out of the rough bark in which early success has encased him.

He could do worse than to study the warmer emotional temperature of Fagan’s book, or the way she uses it to defrost her battle-hardened heroine — the “girl with a shark’s heart” who cleaves to her own moral code (“you dinnae bully people, ever”) and who finds herself fighting back unaccustomed tears when a fellow inmate commits suicide. “I wish that would stop,” she says of this “teary” stuff. But it won’t. Under the guidance of Angus, the one support worker she likes — possibly because of his green dreadlocks and Doc Marten boots — Anais retraces her tangled journey: her 147 criminal charges, her years in foster care, her possible birth in an asylum, where they find a mad old monk, guarded by gargoyles, who claims to have laid eyes on her “bio mum,” although Anais remains convinced that “in all actuality they grew me — from a bit of bacteria in a petri dish. An experiment, created and raised just to see exactly how much . . . a nobody from nowhere can take.”

Sometimes Anais catches glimpses of men behind the prison windows, men with no noses in shiny shoes and black wide-rimmed hats — or are they just an acid flashback? Do we really believe she is being watched? Anais and her fellows are too free to come and go (there are boat trips and double dates, even spending money) for the Panopticon to strike a truly Orwellian note. If this is Orwellianism it’s the well-meaning Orwellianism of the modern European welfare state. With its orphaned heroine, retro prison design and Gothic accouterments, “The Panopticon” glances instead back to “Jane Eyre” and all those other 19th-century novels in which children trace their parentage through a perilous maze of orphanages and poorhouses, those hulking, soot-stained establishments now having made way for the bright, Formica-covered spaces of the modern-day detention center and rehab facility.

Like Stieg Larsson, to whose Lisbeth Salander the spunky Anais also owes a small debt, Fagan plugs into our fears of youth brutalized by the very system that is supposed to care for it, while upending those fears with a heroine who would rather choke than ask for our pity: “I hate saying please,” Anais tells us. “It makes me feel cheap. I hate saying thank you. I hate saying I need anything.” But Fagan’s voice is her own, a pure descant, rising from the fray like a chorister in a scrum. “Vive le girls,” she writes, with “hips and perfumes and perfumers. Vive absinthe and cobbled streets, vive le sea! Vive riots and old porn, and dragonflies; vive rooms with huge windows and unlockable doors. Vive flying cats and cigarillo-smoking Outcast Queens!” Vive them all, yes indeed, and vive Jenni Fagan, too, whose next book just moved into my “eagerly anticipated” pile.

Tom Shone’s new book, “Scorsese: A Retrospective,” will be published next year.

A version of this review appears in print on July 21, 2013, on page BR1 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: Surveillance State.