Ray Foy's Blog, page 13

October 6, 2013

the wider world

When

Josh Bernstein spoke

at The Digital Government Summit on Jan 26, my wife and I were on our way to New Orleans for a couple of days of recreation and a much desired change of venue. So rather than spend a day amid presentations of widget-counting with a garnishing talk about "here's a life you'll never lead," I opted to travel with my loved one to a city of old spirits and seek inspiration by engaging reality. I wanted to

act

, and not just listen.

When

Josh Bernstein spoke

at The Digital Government Summit on Jan 26, my wife and I were on our way to New Orleans for a couple of days of recreation and a much desired change of venue. So rather than spend a day amid presentations of widget-counting with a garnishing talk about "here's a life you'll never lead," I opted to travel with my loved one to a city of old spirits and seek inspiration by engaging reality. I wanted to

act

, and not just listen.We had not been to New Orleans in at least two years and had considered going someplace new, but with a limited budget and travel time, it seemed best to go the place that is close, familiar, and with a specialness for us both (see Sun Feb-10-2013: Love). So I booked us a couple of nights at the Queen and Crescent on Camp Street and we made the four hour drive on a day with a forecast for rain, but that turned out clear and warm.

We found our hotel room to be small, but clean and cozy. The hotel was older but the staff was friendly and though there was no pool, it had cable and wifi. Breakfast was free, but it consisted of a meager buffet of bagels, toast, boiled eggs, cereal and oatmeal. There were two choices for coffee--one OK and the other bad. The hotel was a good place to rest, watch TV, and check the web, but that's all. There was a lounge that looked interesting, with two windowed sides overlooking the street, but we didn't try it. We didn't stay in the hotel much, anyway. We hit the streets pretty soon after our arrival.

On our first day, we walked down Camp in the late afternoon light and felt the cool shadows slipping among the tall buildings to pad our way out of the business district to Canal Street. There, we turned south with the intention of checking out the Riverwalk. We passed Harrahs and the trolley rails and reached the ferry terminal. We made our way along the river's edge where the jazz cruises were waiting for their evening fares. Beyond the expansive, moldy, metal fountain we reached the Riverwalk entrance only to find the mall closed and barricaded. We could see that extensive remodeling was going on inside, so there would be no shopping there this trip. It was just as well since we had little money for shopping, anyway. So we turned about and headed for the French Quarter.

We crossed Canal and headed down Carrollton Avenue. We passed Jackson Square where street performers were drawing a crowd and mule-drawn carriages were lined up waiting for their fill of tourists. Beyond all that lay the Cafe DuMonde where we had coffee and beignets. The treat gave us an energetic second wind and we pushed on to the French Market.

The French Market is a huge flea market with resellers for all kinds of things displaying their wares--even produce items. There were several sellers of African clothing (judging by the signs and that the sellers were black people with African accents) where Donna found four dresses she liked.

At one point, a rack of hats caught my eye and I investigated. I felt drawn to one rack of straw hats in a very tight weave (far more so than in the Bahama golf hat I picked up on Block Island) and a classic fedora-style shape. I tried on on and it struck me as a "writer's hat" for some reason, and Donna thought it suited me. The saleslady showed me a tan-colored version that I settled on. I'm wearing it in the accompanying photo.

With these purchases, we had spent most of our cash. Nevertheless, we headed from there to Bourbon Street.

It was just late afternoon so the hard partiers hadn't hit the street yet, but then the party never really stops on Bourbon Street. A crowd had gathered around some street performers who were dancing to some recorded music. We skirted them and followed a trail of music that was more from our era. We stopped at a lounge where a fairly young band of guys was playing 70's music, and doing so very well. We listened for a while and I was struck at just how well these guys knew this music. They had to have hours and hours of practice behind their performance. And the crowd they were playing for was couples our age and older, who were partying like they were still eighteen. I think they're a significant market for Bourbon Street.

After a while, we pushed on to a couple of other places with bands playing similar music to similar crowds. In one place there was dancing and one old guy was really cutting the rug. He was older than me but he must have been heck when he was twenty. Of course, he wasn't the only one; there was a pretty good bunch of older dancers and some young ones, too. They were all pretty much dancing the same way so it was an interesting blend of generations in a common party mode.

I didn't have the same spirit so I didn't dance. Age tempers my "partying." Still, Donna danced for me and out-shone them all. She always supplies my lack.

The weather was beautiful during our time there, though a bit hot. We walked the French Quarter anyway and held up very well. We didn't eat rich, though. Since our funds were small, we took advantage of the hotel's free "breakfast" and otherwise ate at McDonald's, Subway, Popeye's, a food court, etc. It worked in that we didn't have to go into debt over this little trip.

On our second day we decided to do McDonald's on Canal Street for lunch. Walking there, we passed a young black woman who cried out "Don't touch me!" as we passed. I'm not sure her cry was meant for us, but we kept a wide berth. She said no more and just stood there wearing a backpack.

In McDonald's, we got our food and took our seats at a long counter. At one end, two black men were eating and discussing religious matters. It wasn't so much a discussion, though, as one of them was obviously dominant in the theme. The listener left and soon the young woman from outside passed through. She said something "off the wall" to the religious man and it was apparent she was one of the mentally ill homeless. We fell sorry for her and the man tried to offer her some of his food but she wouldn't accept. She just demanded to know where her steak was. The man said he had no steak and she left.

The episode led to a conversation between Donna and the man who said he had been preaching on the streets for some 30 years and often dealt with people like the young woman. He said there was really no helping them and that the city needed to provide shelters. He went to say he had been preaching in New Orleans for the last 12 years, mostly on Decatur Street. That's when I noticed the bullhorn on his table and an image came to mind. He was a nice guy and I suspected his sympathy for the street people was real.

Later, as we were wandering down Chartres Street, we came upon the Crescent City Bookstore. It caught my attention from its big sign and I felt compelled to have my picture taken in front of it. After all, I was wearing my writer's hat. We didn't go in, though. I had the feeling it specialized in old editions and catered to collectors. That might not have been true, but a lot of New Orleans is like that. In the midst of 150-year-old buildings and voodoo shops, you'll find an antique or clothing store catering to the elite.

We moved on and passed a street musician who called out to us because we were holding hands and wanted to play a song for us. I expected a love song but he launched into a talk about the blues and then sang a song about being down but surviving because he found the Lord. What? When an older couple walked by he did the same thing but sang for them, The Sea of Love. Maybe it's my crusty exterior. Still, he was a good musician and I tossed a dollar in his guitar case.

Passing down Canal again we reached Decatur where our friend from McDonald's was preaching over his bullhorn. I should have taken a picture. Sitting there, bellowing out a fundamentalist "sermon," he was as much a street performer as the bluesman we had just left.

Further down the street, we saw a marquee for the Sanger Theatre announcing that Jerry Seinfeld would be performing there tonight. We headed for it to see how much tickets were. The theatre had apparently been renovated and a lot of work was still going on around it. Seinfeld's performance must have been its inaugural because there were people in suits talking to apparent reporters and getting their picture taken. In the lobby, there were people dressed nicely coming out of the theatre and milling around tables of food. They all ignored us. We asked about tickets at a counter and a nice lady directed us to the box office next door.

We found the box office and it was also being worked on, though it displayed an "open" sign. We asked a somewhat harried, but well dressed, man behind a glass about tickets and he searched his computer. He said they were sold out for tonight but had seats available for tomorrow night. We would be gone by then so we declined. We never learned the cost.

The impression I got about the Sanger Theatre and the Seinfeld show was of entertainment industry types working up their big show in picturesque New Orleans. They were going about their business catering to each other and their 1% clients while we, rudely dressed, scurried among their legs, just tolerated. Money makes the difference, in their eyes.

It would have been nice to have seen Seinfeld, but we probably would not have been able to afford the tickets.

That night, we relaxed in our room and watched a cable movie. It was the George Pal classic version of H. G. Well's The Time Machine. The time theme reminded me of the age gradients among the patrons in the lounges we visited. The older ones were defying time by dancing like they were young, and the younger ones were unaware that time would pass.

Then I thought about the musicians in the clubs and on the streets. Many were quite good, as were the artists in Jackson Square, along with the carriage drivers and fortune-tellers. These were people doing what they wanted to be doing and surviving at it because they would rather "be the poor slave of a poor master" than live like "them" (i.e., those of deluded thinking who equate money with success and happiness, who stare at computer screens in cubicles and count widgets). The street preacher was like that. Though I didn't agree with his message or would want to live like him, still, he was obviously very fulfilled in his work.

All these are living in the wider world, engaging it and dealing with it on their own terms. Selling, cajoling, sometimes conning to get by, they are mostly living as they wish. Rough and crude, in a Walt Whitman way, they play music, read palms, paint pictures of French Quarter scenes or draw tourist caricatures. It's their life and not their job.

The next day, Donna and I packed up and bid New Orleans farewell once again. We returned to our jobs.

Published on October 06, 2013 09:00

September 29, 2013

reality in fiction

I recently posted a review of Louis L'Amour's

The Haunted Mesa

in GoodReads. I noted in that review that I read the book because I wanted to see what L'Amour's writing style and storytelling were like. You see, where I live (the deep South) most people read the Bible and Louis L'Amour novels (not necessarily in that order) and not much else. So I wanted to confirm my belief that I would find a simplicity of prose and literary technique, or be surprised at my conjecture's repudiation. I found some of both.

I recently posted a review of Louis L'Amour's

The Haunted Mesa

in GoodReads. I noted in that review that I read the book because I wanted to see what L'Amour's writing style and storytelling were like. You see, where I live (the deep South) most people read the Bible and Louis L'Amour novels (not necessarily in that order) and not much else. So I wanted to confirm my belief that I would find a simplicity of prose and literary technique, or be surprised at my conjecture's repudiation. I found some of both.I'm not going to rereview the book here. You can find my review at the link above. I just want to mention some aspects of the story that I feel are outside the context of literary criticism. But first, I do need to repeat a couple of points from the review. The storytelling is very much a "western" formula with a simple, straightforward prose style. I say that not so much as a criticism as an observation. Many people like that style (i.e., L'Amour's huge fanbase) and I think, for L'Amour, it came from writing for a particular market--the descendants of the "dime novel" magazines, contemporary western magazines, and the movies. These markets wanted formula westerns and L'Amour produced them abundantly and successfully.

So the western formula part I expected. The part I didn't expect (but hoped for) was L'Amour's pushing the western story envelope to reach into speculative and even paranormal realms. It wasn't great science fiction or fantasy but I expect it was leap of courage on his part to make the attempt. I really don't know how his fans received it (this was his last published book, I think) but I believe he deserved kudos for trying.

In my review, I listed six literary criticisms of the book that led to my 3-star rating. I have other criticisms that I didn't mention that are more philosophical than literary. In The Haunted Mesa I see them in the story's treatment of American Indians, women, violence, good-and-evil, and it's idea of "progress." I won't talk about them all, only the most glaring, which is his treatment of the Indians.

Since I'm a fan of Daniel Quinn's Ishmael books (see my review links below) the sections that talked about the Indians struck me as prejudicial against them in the sense of "Mother Culture's" bias against tribal peoples. Since the plot of The Haunted Mesa is based on the "disappearance" of the Anasazi ("Ancients Ones"), I read up on them in Jared Diamond's Collapse.

The Haunted Mesa speculates that the "evil world" the Anasazi came from, according to their legends, was another dimension and that they entered ours through "portals." When things got rough here, they returned to their home dimension. The Haunted Mesa paints the Anasazi as a peaceful people who were on the verge of discovering the "progress" of agricultural-based civilization but were impeded by the incessant warring upon them by those other dang tribal people. So they took to living on hard-to-attack cliffs for protection, but were still vulnerable when they came down to tend their fields and so couldn't hang on. They had to return to their home dimension, even though it was an "evil place."

That is the premise The Haunted Mesa's plot is based on, and it's fiction. It contains the idea of a lesser people who were always fighting one another and so could never get ahead. This idea is certainly not unique to L'Amour, but he says it like this:

Several attempts were made to construct a more advanced way of living before the coming of the white man, each of which was destroyed by nomadic invaders. This obviously happened to the Anasazi and a similar thing must have happened to the Mound Builders...What would they (the Anasazi) have become had they remained here and been able to resist the attacks of the wild nomadic Indians who were coming in from the North and West? How would their civilizations have developed?

Actually, according to Jared Diamond, the Anasazi civilization collapsed after about 600 years from resource depletion (some 400 years before Columbus showed up). Their environment was fragile to begin with, but they brilliantly exploited it and populated it to the point they even expanded into surrounding areas. But eventually they used up the pineyot and juniper trees they needed for building, cooking, firing pottery, and warmth. Then a huge drought that their large population couldn't bear did them in. Their "escape" was to a level of less complexity, absorbed by the Hopi and the Pueblo.

As depleting resources put pressure on their numbers and complex society, the Anasazi certainly did fight among themselves. I imagine it was basically a fight for survival--the biggest and meanest taking from those less able to defend themselves, until it was all gone. There is even evidence of cannibalism during this time, but none of "wild invading nomads." The Anasazi were just too isolated from the other North American tribes for that to be a factor (at least during this time period; though that part of the southwest is still pretty isolated today).

Lessons to be learned for our time should be apparent. From the broadest view, our highly complex civilization is facing a fundamental resource depletion no less than did the Anasazi. And the results are the same--starvation and fighting over what's left. Our only escape will be to a level of less complexity.

With regards to fighting, L'Amour goes on to say:

Our Indians warred against each other, just as did the Mongol tribes before Genghis Khan welded them into a single fighting force. Tecumseh tried to do the same thing in America, and so did Quanah Parker, but any chance of uniting them against a common enemy was spoiled by old hatreds and old rivalries...In almost every war the white man fought against Indians, he was aided by other Indians who joined to fight against traditional enemies.

This strikes me as biased towards Indians, coloring them as savages. Why is a hierarchical, exploitative way of life more "advanced" than tribal living? "Technology" is an inadequate answer. The common put-down of saying the Indians were constantly warring with each other, and they couldn't unite because of old hatreds, is an invalid way of seeing them. It sounds a lot like the idea I often hear that "those people in the Middle East have been fighting each other for centuries and always will." In other words, they're just mindless savages. I think a similar argument was made to justify making slaves of Africans.

Daniel Quinn makes the point that American Indians (and other tribal peoples) fought, but never to any tribe's extinction. They didn't conquer and exploit or take slaves as a vital part of their "economy." They didn't understand the difference in the white man's way of warring from their own. They didn't see that for the white man it was to conquer-to-exploit to extinction. By the time they did, it was too late.

In any action story, there is the temptation to have "evil widgets" that are there only to throw against the protagonist, giving him something to fight and so make him look braver and stronger. Note the stormtroopers in Star Wars, the orcs in The Lord of the Rings, the Nazis in old WWII movies, and the Indians in old westerns. It's a plot device but it's simplistic, hack, plot device. It can promote cruelty and racism. Surely, we can strive for a greater depth of understanding, even in our fictional worlds.

In recent years, there has been some attempt to show a more realistic view of who the American Indians were. Dances with Wolves for example (which was basically remade and set in the future as Avatar). What it amounts to is being tolerant of other people, their views and ways of life, and of being more honest in the telling of history, even in fiction.

---------------------

Links:

My review of The Haunted Mesa

My review of Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit

My review of My Ishmael: A Sequel

Published on September 29, 2013 13:06

September 15, 2013

seeing wonder in the mundane (or, "josh and me")

I received an email this week at my day job, inviting me to attend the

Digital Government Summit

. It was described as:

I received an email this week at my day job, inviting me to attend the

Digital Government Summit

. It was described as:...the premier event where government leaders can focus on enabling technology to be an effective tool to streamline government and provide vital services to our constituents.

And furthermore:

Government leaders will have the opportunity to hear from industry experts on topics such as BYOD, Information Security, Social Media and Cloud Myth Busters and more.

Now, I'm not a government leader and the hype sounded too corporate to suit me. These things tend to be tenderizers for tech vendors or, worse, propaganda platforms to lay foundations of acceptance for worker-exploiting technology (you're always at work if they can reach your smartphone), cyber-fear mongering, or "trust your data to the 'cloud'" mythology. So I was about to delete the email when I noticed a paragraph about the keynote speaker:

The day will begin with a fascinating opening keynote presentation: Josh Bernstein – International explorer, photographer, author, and television host who has traveled more than 1,000,000 miles by train, plane, bus, bike and camel to over 65 countries, exploring the biggest mysteries of our planet in pursuit of knowledge discovery.

Whoa! Josh Bernstein! Host of History Channel's Digging for the Truth , the ardent explorer who searched for the lost ark for real, who investigated the truth behind The DaVinci Code , who explored the caves where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, who crawled through the narrow passages running through the Great Pyramid at Giza, who dived the Mediterranean looking for Atlantis, sports chin stubble, wears camp shirts and a hat, who stepped into a bed of fire ants on the banks of the Mississippi! Dude! Josh Bernstein!

Yeah, I used to watch Josh on the History Channel back when I thought I could afford a big cable package. I liked his Indiana Jones persona and thought-provoking, real-life explorations. And now he's coming to my town to speak at an event that promises otherwise to be a day of mind-numbing boredom! How could that be? Where on earth was the tie-in that would make him a keynote speaker for a conference on Government IT?

So I pulled up the website that contained the conference agenda. It noted that Josh's talk was entitled, "Exploration is a State of Mind," and there was a blurb:

In a fast-changing world, everyone is an explorer whether they know it or not, particularly in government IT. We are constantly traveling across uncharted terrain: the economy, social media, the cloud, and on and on. Was Steve Jobs any less of an explorer than Ferdinand Magellan? They definitely had one thing in common: they always looked forward and rarely looked backward. The spirit of exploration and adventure lives on, now more than ever because technology makes it possible for anyone to be an explorer in their own right. In this fascinating and rousing session, noted explorer Josh Bernstein shows us how to turn one's career into an adventure and the survival skills needed along the way.

I see. Josh is going to tell us that we can all be explorers in our minds and turn our jobs into adventures--sitting in our cubicles, day after day, staring at a monitor and counting widgets. Please pardon my cynicism, but I've danced this dance for a long, long time.

Now there is something to be said for being able to look at the drudgery of common life and see the miraculous. But what makes a quixotic view foolish or genius depends on whether it is grounded in delusion or vision. If you tilt at a windmill believing it to be a giant, you'll only get hurt. If you see it as a metaphorical giant, then you might find some insight to battle your real problems.

Emily Dickinson expressed the latter in most of her works. Indeed, her life was pretty much seeing wonder in the mundane:

To invest existence with a stately air,

Needs but to remember

That the acorn there

Is the egg of forests

For the upper air!

So there's potential in Josh's topic. It could be that he will present the possibility of finding that "unearthed jewel" that he has seen in so many travels, that can stir our imaginations to see Timbuktu in a spreadsheet of widgets. I hope the Summit audience does find that in Josh's talk. I believe many of them enjoy--indeed, are passionate about--counting widgets. I was at one time. Now, it's not enough.

I'm sorry, but Steve Jobs was very much less of an explorer than Ferdinand Magellan, and the cyber terrain we cross is very much traveled. In fact, it's fool's gold and polluted waters. It's a maze of mirrors that we need to escape.

I noticed on Josh's website that he offers himself for hire as an inspirational speaker. He provides a number of topics that you can choose from and he'll tailor your choice with a slant appropriate for your audience. That's obviously what the promoters for the Digital Government Summit did and it was a good idea. Mr. Bernstein will attract a larger attendance for them. If his talk's connection to the conference is rather strained, few will notice or care and I've no doubt but that he will be the highpoint of the day.

I won't be attending the Digital Government Summit because it falls on a day I had scheduled to be off, and my intention is to spend some time with Donna in New Orleans. So I won't hear Josh's talk, but that's probably just as well. While I'm sure I would draw inspiration from it, I would also leave it frustrated at having glimpsed the wider world only to return to my cubicle.

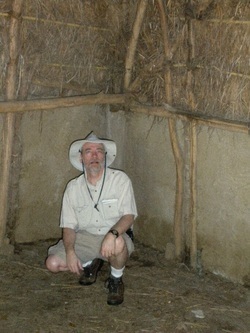

I recall Josh did an episode of Digging for the Truth in Natchez, Mississippi. He visited the Grand Village of the Natchez Indians, which is a state park within the Natchez town limits. It contains a museum and several mounds built by the Natchez Indians on which they constructed temples and dwellings for their VIPs. There is also a reconstruction of a thatched, mud-and-wattle house of the kind the Natchez lived in. In the Digging episode, Josh sat in a corner of this house and talked to the camera.

I remembered that image when Donna and I made our own visit to the Grand Village several years ago. We saw the relics in the museum, climbed the mounds and hiked the woods along the creek that borders the park. I wanted to get a feel for life the way the Natchez lived it as an inspiration for the Dentville books I was considering (and am now writing). We also visited that reconstructed Indian house and Donna took my picture as I sat in the same spot where Josh had been (it's the picture that heads this journal entry).

That picture says something to me about living in the same world as an adventurer/explorer that I admire, and the possibilities for fulfilling dreams and living better, more inspired, and spreading that inspiration through my written words. It whispers to me the hope of escape from the mundane to realms of wonder that surround us all.

Josh Bernstein's website: www.joshbernstein.com/site.php?/home/

Published on September 15, 2013 06:11

August 31, 2013

the right thing to do

I've just finished reading

Cloud Atlas

by David Mitchell and posted a review of it on Goodreads. You'll see that I liked it very much. I thought it was engaging storytelling with themes I relate to. One of those themes is the idea of civilization's collapse. One of the "novellas" within the novel is set in the far future when human civilization has totally and irrevocably collapsed ("the fall"). The cause of the collapse is intimated to be from the destructive systems that humanity had created. That is, human "progress" had reached a point where it began to feed on itself and so ultimately destroyed itself. It strikes me that this theme is surfacing more and more in books and movies.

I've just finished reading

Cloud Atlas

by David Mitchell and posted a review of it on Goodreads. You'll see that I liked it very much. I thought it was engaging storytelling with themes I relate to. One of those themes is the idea of civilization's collapse. One of the "novellas" within the novel is set in the far future when human civilization has totally and irrevocably collapsed ("the fall"). The cause of the collapse is intimated to be from the destructive systems that humanity had created. That is, human "progress" had reached a point where it began to feed on itself and so ultimately destroyed itself. It strikes me that this theme is surfacing more and more in books and movies.I wonder if the recurrence of this "collapse" theme comes from a general pessimism that pervades the western world. Though denial is rampant, especially in the US, most people seem to subscribe to the idea, if only subconsciously, that things are out of control and that our children's lives will be much harder than our own (or even that of our parents); that life for the most of the earth's population will degrade. The "why" of this collapse is a broad subject that I think most people have a hard time comprehending because the popular media obfuscates the subject so much. But there are reasons--hyper-capitalism, global corporations that corrupt governments, climate change, population over-reach, and (cheap) fossil fuels depletion. The last is greatest driver of collapse because technically advanced (i.e., digital) civilization came about only through cheap, highly concentrated energy (i.e., petroleum). That's gone now, so trying to sustain a complex civilization with endless economic growth is an endeavor doomed to fail. Collapse to a simpler level is inevitable. But what is that simpler level and will we survive the fall to it?

Regular readers of this journal know I'm working on my own "post apocalypse" set of stories under the general title of Dentville . As I work on it, I sometimes wonder if the world I'm painting is too optimistic. Even though the world of Dentville is ravaged, I'm positing a tribal existence for humanity's survivors that at least has some structure to it at a kind of neolithic-medieval level. In Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell describes the fall as going lower than that. The reason for my wondering is that I sense a ponderous evil running our current world.

For example, the mainstream news this week has been mostly about the imminent US attack on Syria. It has largely been a propaganda push for the attack and subsequent war to happen. As with Iraq, the US excuse to pursue war is paper-thin and highly unconstitutional. Despite the popular media's claims to the contrary, the evidence is that the gas attack on civilians outside of Damascus was perpetrated by the "rebels" rather than Syrian government forces. So it's another false-flag to provide an excuse for war. The US administration seems unconcerned that there's no support for a Syrian war among US citizens (only about 9%, though I expect that figure to rise), that the UN won't support an attack, or that the British parliament just voted to not support an attack. But the mind-boggling evil part is that children were gassed in an apparent ploy to make the crime to be pinned on the Syrian government more heinous. This world is ruled by psychopaths .

[BTW, I'm not defending Syrian President Assad. He's no sweetheart and probably should be overthrown. But the revolution should be by and for the Syrian people, not imposed by western corporate powers that desire only a more compliant (to them) dictator.]

So what do you do? How do you cope in a world like this? Do you just hope to survive its violent thrashings as it self-destructs?

Cloud Atlas suggests a response of action. Mr. Mitchell says that collective action by good people can eventually overcome the numbers and technological advantage of the bad ones that oppress. That may be true, but it would likely take a longer time than civilization has left. So a "wait and survive" strategy might also have merit. Or some combination strategy might be best--we wait while we struggle against evil. And it has been said that we struggle, not because we can win, but because it is the right thing to do.

LINKS: My Cloud Atlas review on Goodreads

Published on August 31, 2013 12:33

August 18, 2013

gaming and storytelling

My sons are home from college for summer break. They've spent most of it taking classes at a community college and studying (the hours will transfer to their university). Now those classes have ended and they're relaxing by catching up on some video games.

My sons are home from college for summer break. They've spent most of it taking classes at a community college and studying (the hours will transfer to their university). Now those classes have ended and they're relaxing by catching up on some video games.Like most young people these days, they've grown up with video games. They've always preferred those with storylines over sheer action and gratuitous violence. They especially like the Legend of Zelda games, which I've come to understand is a cult classic among gamers. Watching my sons play it and listening to them talk about it, led me to speculate that this is their generation's "reading." That is, it is the activity--even beyond movies and cable TV--that provides them with the storytelling component of their entertainment in the place of books. I wanted to dig a littler deeper and try to verify my conjecture.

So I watched my sons play their latest Legend of Zelda game (Skyward Sword). They even showed me one of the earlier versions of it (The Ocarina of Time). I found there is a basic story behind these games that is retold, though with some variation, in each new release. The core story has the game's protagonist (named, "Link") fighting monsters and villains, evading traps, and collecting tools and clues as he journeys through the world of Hyrule (and its "subworlds") searching for the lost (or abducted) Princess Zelda and/or some desired artifact (the triforce of courage). This is, of course, the classic hero's journey in folklore and fiction (i.e., the Quest).

There is an involved lore surrounding the Zelda games that engrosses fans, and over the years they have debated how all the game versions fit within the chronology of this lore. They have sought a consensus on which games and offshoot stories (there was even an animated, 13-episode TV show) actually fit the lore and so establish a canon. Finally, in December of 2011, the game's maker, Nintendo, published an official chronology, "outlining how the games in the series are related to one another" (see the links below). I suppose that closes the canon.

This fan's devotion for Zelda lore is not unlike that for stories long spun by the bards of humankind from The Epic of Gilgamesh to The Odyssey to Sherlock Holmes to Star Trek to The Lord of the Rings. The latest twist is the element of interaction. When playing the game, you are the hero. You decide where he/she goes and what she/he does. You figure out the puzzle and find the treasure, beat the enemy, or rescue the Princess, though you die a thousand deaths in doing so.

Video games literature (found mostly on the Internet) verifies the dichotomy of game play vs storytelling and that there are aficionados for each. Today it is common for games to have both elements, though usually with a greater emphasis on one or the other. Getting to that point required an evolution in video gaming.

Video games basically started with Pong, which I played in 1974. It was just a simple digital version of ping-pong played on a TV screen, but it was fascinating to my generation. It caught on and quickly evolved into the Atari games of the video arcades in the 1980s. These games became the classics that survive to this day in high-def, 3D forms (Donkey Kong can still be found in the popular Super Smash Brothers). Back then, they were strictly game-play (Pac Man) though some were presented with a background story (Vanguard) or at least an implied story (Jungle Hunt). Some experimented with three dimensions, notably, Battlezone where you drove a "tank" and dueled with mechanized attackers. The tanks and landscape were simply geometric figures--just outlines--but the feel of moving through a 3D space was unique for the time. But to really merge game play and story required advances in digital technology.

The introduction of the personal computer, or microcomputer, paved the way for these advances. Microcomputers had long been in development, and hobbyist models were produced by Radio Shack, Commodore, and Kaypro. But it wasn't until IBM produced its version in 1981 that standards were established that gave programmers a common platform on which to develop (and this included games).

Graphics capabilities and raw computing power increased exponentially along with the PC market and allowed the development of video games that were the clear antecedents to those of today. These included Myst, which was mostly an experiment in moving a point of view (POV) through a 3D space. The techniques learned from Myst were incorporated into Wolfenstein, a game played on a personal computer where the POV was escaping from imprisonment by Nazis. You moved through the rooms of a castle, finding items to help you and shooting Nazi soldiers as you come across them.

A fantasy descendent of Wolfenstein was Quake, which brought improvements to the graphics and 3D format. I played this game on my workstation when I had my ill-fated IT job with Sunbeam in 1996. I had not worked there a year before Sunbeam was reorganized to make it profitable again, which led to personnel layoffs. When I received my notice (along with the entire IT department--grist for another journal entry) I was still retained for a few weeks just in case something went wrong with the servers. I was told to do nothing but fix things if they broke and that's just what I did. Beyond that, I procured a new job and played Quake while I waited for my current job to run out.

Quake was the only video game of its kind that I really got into and played through to the end. That ending involved facing a giant, Satan-like character, and the weapons I had used up to that point were not effective. There was a trick to beating this guy, but I couldn't figure out what it was. I finally found the source code for the game on the Internet and followed it enough to learn the secret of how to beat the game.

Fast-forward to now, when I'm trying to write stories that grab people's imaginations and make fans. Understanding the current allure of video games, I believe, provides clues that could help me. One is that for a large part of the game-playing masses, the storyline is important. So important that Nintendo executives felt compelled to produce a comprehensive chronology for their Zelda games. Whether through digital interaction, dramatic recreation, or sheer imagination, people want to experience a story. They want to know the characters, where they came from, and where they're likely to go. And in the end, they want to have some sense of closure, problem solved, villain beaten, game over, though with the sense that life for the characters will continue.

So my big take-away from considering video games: they are the literature for generation X. You might aver that it's a shallow literature, and with some justification. It's hard to imagine an interactive game that captures the expansiveness of The Lord of the Rings, or the deep psychological levels of Moby Dick. Still, some have come closer than you might think. I suspect video games are really just another medium for the storyteller to use if it suits his or her purpose. Perhaps they will keep the storyteller's art alive through the digital age and convey the truth of fiction to plugged-in gamers, until we reach the next phase that returns that sacred function to the printed page.

LINKS:

Legend of Zelda in Wikipedia

The official Zelda chronology in Wikipedia

Published on August 18, 2013 06:15

July 27, 2013

everything old is new again

When trumpets were mellow

When trumpets were mellowAnd every gal only had one fellow

No need to remember when

'Cause everything old is new again

I remember my parents and their friends talking about the radio programs they listened to in their youth. In the 1930s and 40s, before television, broadcast radio was the popular medium that brought entertainment and news to American households. Though music was a large part of what was broadcast, it was usually not recorded music, but live broadcasts of performances. Beyond that, entertainments were the same popular fare, as on television in later years: dramas, comedies, soap operas, even game shows made up the daily programs of broadcast companies like CBS and RKO.

When I was a teenager, I received a Christmas gift of several record record albums (the pressed vinyl type) of old radio programs and so got a sampling of what my parents' generation listened to. A lot of the actors in these programs were familiar to me because many were still making appearances on the TV of my time--George Burns, Jack Benny, William Conrad, Orson Welles, and others. And a lot of the programs were classics that were later redone as TV programs and movies--The Lone Ranger, Flash Gorden, The Shadow, Tarzan, Gunsmoke, etc.

And people got their news via the radio, probably more so than newspapers (although many people of that generation seemed to have been fanatical about their newspapers). Some news broadcasts and broadcasters achieved fame--the eyewitness account of the Hindenburg disaster, the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936, Winston Churchhill's broadcasts during the London bombings, and Lowell Thomas' broadcasts from his world travels.

Radio was the medium of the twentieth century that chronicled life between the world wars and through the second one. It did so even more than film--though WWII was heavily filmed--because radio was ubiquitous in western households, especially in the United States. People followed the war news on the radio, taking reassurance from voices they came to trust. These were usually male voices that resonated as strong, paternal figures like Edward R Murrow and even President Roosevelt (hard to imagine a US President as a reassuring figure, but such were the times).

And speaking of voices and drama, my records included the complete dramatization of The War of the Worlds featuring the voice of Orson Welles. This was a reworking of H. G. Well's classic science fiction novel about an invasion from Mars that was presented as if it happened in the present day and reported on by radio news. It was broadcast on Halloween of 1938 and was so true to the nature of the news broadcasts at that time, that many people who caught only portions of it, believed that an invasion from Mars was actually underway (this may be a comment on the naivete of the time, but I doubt we're much better now).

People I knew who had experienced radio of those decades tended to speak of it with a wistful nostalgia. I think this was partly due to radio being the "voice" of those turbulent times and partly because of the nature of the medium. Radio, when it's not just blaring music and ads, is intimate in a way that video mediums can't be. It's a comforting voice that feels as if it's speaking to you alone, prompting you to imagine the speaker and the actions he or she describes or conveys only by sound.

Radio never went away with the advent of television, but it changed to being mostly a platform for selling music to the public. Then slowly, over the last decade, it came back, somewhat, to being something more. Actual news and talk shows (mostly from the political right) found niches in broadcast radio and some were quite good, but I still didn't see in them that intimate quality or drama of radio's heyday.

Then I discovered podcasts. For the longest time, I had heard about them but never investigated. I became curious when my sons mentioned they were popular among the college set and I was thinking of ways to connect my fiction work with an Internet-based audience. It seemed podcasts were a natural for ipod and smartphone users since they were easy to produce and very "portable."

Podcasts are just recordings facilitated by personal computers into sound files that can be played back on any device that can read them--computers, ipods, ipads, smartphones, even CD players. The podcasts themselves are "radio broadcasts" of people doing interviews, or speaking their blog posts or otherwise reading their written works, or just speaking from their soapbox.

Where I really appreciate podcasts is on my commute to my day job. My car stereo will play mp3 files it finds on a flash drive inserted into its USB port. Every week, I download my favorite podcasts and play them during my commute. A lot of people must do this because most podcasts are 40 minutes to an hour in length--the average US commute time. This allows me to fill a lot of mandatory "free" time with some inspiring and though-provoking talk instead of the constant popular or oldies music, or propagandic news and banal, far-right chatter.

What I like to listen to are interviews of interesting people talking about interesting things (as I judge them, anyway). These are among my favorites:

Dreamland. This is Whitley Strieber's show where he interviews people about topics on the fringe. These topics are UFOs, Bigfoot sightings, ghost encounters, hidden history, and the paranormal in general. It's intelligently done and Whitley brings his experiences and erudition to every episode.

The Kunstlercast. This is James Howard Kunstler's podcast and is generally my weekly favorite. James is a colorful speaker and writer, and most always has an interesting guest speaking about subjects that include sustainable living, peak oil, and high-tech collapse. His interviewees have included notables of this genre like Richard Heinberg and Dimitri Orlov. This podcast especially captures that intimacy factor in the format of it's introduction of folk music that would be at home in a 1930s broadcast. James' voice also has a timbre reminiscent of the old programs, though he will at times use language that would never have been broadcast back then.

Citizen Radio. Speaking of language you would never hear in the 1930s, you'll hear a lot of it here, with wild abandon. This is a podcast by Jamie Kilstein and Alison Kilkenny. They are married and he's a stand up comic and she's a writer who has been published in The Nation. Their banter can get hyper and is on the level of today's stand up comics, so there's a lot of the F-word thrown around. But they talk about current events from a decidedly left-end of the political spectrum, with a lot of humor thrown in. They are an acquired taste, but I've become a fan.

Writer's Voice. I love this one. Every week, an author or two (fiction and nonfiction) is interviewed and they talk about their book and what it's about. This makes the subjects very far-ranging, from politics, to romance, to family relations, to sustainable living (James Kunstler had a good interview here). As an aspiring writer, I love to hear those episodes where an author talks about the writing process, but the discussions are most always inspiring whatever the subject. The main hostess, Francesca Rheannon, is a very capable and informed interviewer.

So it seems to me that the current advent of Internet-based podcasts has recaptured some of the flavor of old time radio, especially in the interview-based podcasts. What I haven't seen, so far, is a return to "radio show" drama. I don't count audiobooks. I mean a dramatic work (an "audio play") or situation-based comedy. There may be some out there but I haven't run across them and there's certainly nothing like the old "Mercury Theatre on the Air" doing drama. I'll bet there's a podcast niche for drama done intelligently with contemporary themes.

As I proceed with my Dentville stories and website, I would like to find a place to use podcasting. Maybe audiobooks or even dramatic works of my short stories.

That would be a neat thing.

Published on July 27, 2013 17:49

July 13, 2013

Mr. floyd's deception, part ii

"The best short stories are those that touch us in our personal spaces--like a song that vibrates our heart chords with just the right melody, meter, and words." (From my review of While the Morning Stars Sing)

"The best short stories are those that touch us in our personal spaces--like a song that vibrates our heart chords with just the right melody, meter, and words." (From my review of While the Morning Stars Sing)To me, a good short story is like a song with lyrics or a melody that relate to who I and where I am in some compelling way. It may simply say something that I "amen" too or have a deep understanding for. Arthur C Clarke's The Nine Billion Names of God comes to mind. Being grabbed by a story like this is great, and even better when you have a compilation of such stories. Consuming each over a space of time is like snacking on tortilla chips and rotel dip with a dark larger beer when I don't feel like a steak dinner. Though my tendency is towards epic novels in my fiction reading, in trying to do my own writing I've come to appreciate the art of the short story.

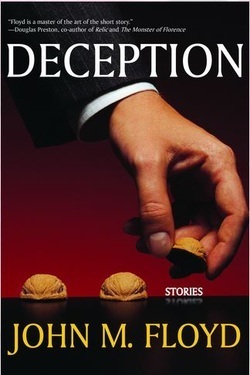

My old friend and writing teacher, John Floyd, has made a career of writing short stories and gotten them published in many prestigious magazines (Alfred Hitchcock, Ellery Queen, The Strand, Saturday Evening Post, to name a few). I just finished reading his latest compilation of short stories called, Deception. I described my purchase and John's signing of this volume in an earlier journal entry ( 05-May-2013: Mr. Floyd's Deception ).

John is an excellent writer and teacher with a large following in Mississippi. I very much enjoyed Deception and wrote a review of it that I posted in GoodReads and Amazon (links to these are below).

In a nutshell, I highly recommend it as an entertaining read, especially if you love the mystery genre. And if you're an aspiring fiction writer in the Jackson, Mississippi area, John's classes in the Continuing Education program at Milsaps College are well worth the money.

Speaking of short stories, I also recently finished writing one called, What I Call Life, that I've submitted to a local magazine. I dropped everything and spent about two months writing this story just so I could submit it for the magazine's fall issue. It is a story that has been on my mind for years and this was my excuse to tell it. The magazine hasn't accepted it yet. If they do, I'll tell you about it in another journal entry.

One reason I'm even trying to write and publish fiction is the prompt I got from taking John's Short Stories classes (there is a part I and II). He was an example that proved to me it was possible to actually write and publish. Prior to that it was all theory to me--something other people did elsewhere. Now I believe it can be done and am very deliberate in my efforts.

I'm not musical. I can't sing or play an instrument. But I do love music, from Beethoven to Josh Groban to Fun. I've found that my singing is best done in written prose, where I can express my songs in thoughtful tales and ripping yarns. Maybe someday I'll be able to compile them in a volume like Deception and strum some sympathetic heart chords, as John does.

----------

My review of Deception on Amazon.com

My review of Deception in GoodReads

Deception page at Dogwood Press website

Find John's short story writing classes here

Published on July 13, 2013 18:32

July 6, 2013

a fourth of july

Sometimes, you just got to get out of town. Facing a long Fourth of July weekend, Donna and I were feeling that urge. Especially Donna. I was actually reluctant since it costs bucks to travel even locally, and I tend to get into ruts and find it hard to move. I mean, we were behind in the housework, laundry, yardwork, etc. But Donna prevailed and so we spent the holidays visiting family and checking out the Biloxi fireworks display from the beach.

Sometimes, you just got to get out of town. Facing a long Fourth of July weekend, Donna and I were feeling that urge. Especially Donna. I was actually reluctant since it costs bucks to travel even locally, and I tend to get into ruts and find it hard to move. I mean, we were behind in the housework, laundry, yardwork, etc. But Donna prevailed and so we spent the holidays visiting family and checking out the Biloxi fireworks display from the beach.I'll cut to the chase. On the afternoon of the Fourth, a bunch of us packed blankets and a cooler of "soda" and headed for the Biloxi beach. We cruised down I-10 to Ocean Springs and took the Biloxi exit. We reached Highway 90 at dusk. Highway 90 follows the beach along the Mississippi Gulf Coast and The Fourth of July is one of those times that brings a lot of traffic to the highway. People come to watch the displays put on by Biloxi and Gulfport from the beach. Our intention was to see the one put on by Biloxi near the Beau Rivage hotel/casino.

The traffic on 90 was heavy and slow as people looked for good beach spots. The beach was full, though not overly crowded, with people waiting for the fireworks and just funning in the sand. We found a likely place and turned down a road between bed-and-breakfasts to find a parking spot. We did and left our cars to join the procession towards the beach, with my sons lugging the big cooler of "soda," and Donna and her sister carrying the blankets.

The traffic was moving so slow, it wasn't hard to find a pause in it to get across the highway. Then we ditched our shoes and made our way onto the beach. We were not far from the landmark Biloxi lighthouse and the antebellum Welcome Center. The Beau Rivage was in the near distance to the east. We spread our blankets and settled in.

It had been a good while since I had been on this beach. It was as I remembered--an expanse of soft sand though crunchy with broken sea shells and debris. Not unpleasant though. In fact it was nice to be there at sunset with a cool, briney breeze invigorating us after a day of rainy travel and insufficient hotel rest. Breaking into the "sodas" we relaxed and waited for the show.

Actually the show started early because a lot of people around us had brought their own fireworks and started setting them off as soon as it began to grow dark. Some were quite good. There were lots of rockets and roman candles and squealing kids and ooohing parents. The air filled with smoke and gunpowder smells on top of the salty ambiance from the briney deep. We watched and chugged "sodas."

At one point, my sons and I felt the need to search for a restroom. There were no portables on the beach and there didn't look to be any public options close by. It was dark, so we decided to find a spot up the little side road where we had parked our cars. So we left the women at the blankets and hiked back across the highway. We reached our cars and found there were still a lot of people around. So we looked some more and found a road that lead from the back of a bed-and-breakfast and through a space of thick trees and bushes. It was workable for our needs. When we emerged from the thickets, we were hit with a cloud of gunpower amid the sound of fireworks. With the big antebellum bed-and-breakfast in front of us, it was as if we had suddenly transported to some civil war battle.

Then the smoke cleared and we returned to the present and the beach.

At about 09:00 o'clock, Biloxi and Gulport started their shows. Gulfport's we could see in the distance towards the west, but Biloxi's was close by, just beyond the Beau Rivage. It was impressive, with large rockets bursting high overhead, showering colorful and bright sparks and secondary bursts to the delight of the crowds below. This display was joined by even more fireworks from the beachcombers to create an atmosphere of sparks and explosions puncuated by shouts of "America! Duck yeah!" It was almost magical.

After about 30 minutes, lightning from the south was adding to the fireworks so we left the show and returned to our cars. We had a late dinner at The Half Shell and then cocktails in the Beau Rivage casino. Around midnight, Donna and I returned to her sister's house to crash. Others of our party stayed later to dance into the wee hours.

Yes, it was a very nice holiday. My thanks to Donna's family for their hospitality. We returned home late Friday and found the chores still in place, waiting patiently for us. Sometimes, you just got to get out of town.

Published on July 06, 2013 19:49

June 3, 2013

our garage sale

Donna and I had a garage sale last Saturday. We pulled out everything we had in rented storage, stacked it in our garage, put out signs, and started dealing with the roving shoppers at daybreak. It turns out that our neighborhood is a hotbed of garage sales every weekend. The big sign at the entrance to our subdivision had several smaller signs besides ours stuck on it. The stop signs leading to our street were also plastered with sale signs, leading shoppers through the streets like a blazed trail through the wilderness. They led the way to our house and, after an intense four hours, we had sold off our major items and collected a wad of cash. What we didn't sell, we donated to Goodwill.

Donna and I had a garage sale last Saturday. We pulled out everything we had in rented storage, stacked it in our garage, put out signs, and started dealing with the roving shoppers at daybreak. It turns out that our neighborhood is a hotbed of garage sales every weekend. The big sign at the entrance to our subdivision had several smaller signs besides ours stuck on it. The stop signs leading to our street were also plastered with sale signs, leading shoppers through the streets like a blazed trail through the wilderness. They led the way to our house and, after an intense four hours, we had sold off our major items and collected a wad of cash. What we didn't sell, we donated to Goodwill.Selling off our excess and so getting rid of a monthly bill for storage rental represents another step in our downsizing. This is a process that started with the sale of our "McMansion" several years ago. That house was the height of our accumulation of things as measured by sheer square footage and the stuff we filled it with. When we moved from there, we filled that house's big great-room with boxes of possessions. Probably a third of it went to storage and we fit the rest as best we could into the small apartment we were moving to. Our next move beyond that, was a rental house and we reclaimed what was in storage, selling some of it in a significant reduction of stuff. Now we've moved into a house that we've bought. It's smaller than the rental, though better laid out and better constructed. The house is comfortable and works for us. Emptying our storage again is our fitting into it. I see it as a picture of what contraction is--moving from a complex to a simpler mode of living. "Right sizing" is an appropriate term for it--finding that niche of sustainable living within our constraints.

I saw in our garage sale a picture of our personal contraction as the idea of "opting out" that I had run across in articles and podcasts in the preceding weeks. I was especially struck by the comments of the economics blogger, Charles Hugh Smith, when he was interviewed by James Kunstler. Kunstler asked Smith why he thought the American population was so unconcerned, or passive, in the face of economic, political, and social collapse that puts people in the streets elsewhere. Mr. Smith said he didn't think Americans were unconcerned, they just haven't reached the point of being willing to face violence to protest their oppression. Instead, they're resisting more passively by "opting out."

Mr. Smith's comments really struck a chord with me. In-your-face occupations and civil disobedience have their time and place, but nonviolent mass action (or inaction) is ultimately more effective because it is the thing our rulers can't handle. They would prefer open opposition because they know how to use force to crush that (as in the dead-of-night driving of the Occupy Movement from their places of occupation across the country). They don't know how to handle millions of people who simply refuse to buy into the system of endless consumerism that enriches the elites, exploits everyone else, and destroys the earth. At least that's the idea and there is evidence that it's gathering some traction.

Cooperative models for conducting business are popping up here and there. These are the worked-owned companies such as "New Era Windows" that grew out of the workers occupation of the "Republic Windows and Doors" factory after being laid off with just three days’ notice. And young people are learning sustenance farming in the northeast out of a desire to take life into their own hands when their college degrees fail to earn them a decent livelihood. It may be that more and more people are finding even subtler ways of finding alternatives to the corporate, fossil-fuel driven mode of life.

So what's involved in opting out? It's as much an attitude as specific things you do. Here's a couple of plans I've condensed from the writings of some commentators I've come across. The first is from Steve Ludlum of the Economic Undertow website. Steve suggests:

* Get Simple. Avoid interconnected complexities--"Becoming independent from- or less dependent upon

interconnected engineered systems is a way to avoid others’ costs" (which I take to mean McMansions in gated communities, Wal-Mart, smart-anythings).

*Get Small. ("Ditch the growth idea starting at home. Size = vulnerability, giant size = collapse.")

* Get Free. Pay off your debt and don't incur more. (The system makes this difficult, but reduce debt as much as you can).

* Get close to food. (Grow your own, buy from farmer's markets, etc).

* Get Real. Strive for a life unmitigated. Disconnect from iPhones, Blackberries, cableTV, etc.

* Get rid of the car. (Or go to one, small, economical one. If you can live without a car, you are blessed).

* Learn a skill or trade. (Support yourself and aide your community now and later).

* Find a comfortable place to live. (A place that suits you, where you can be part of a community).

I found the next list on The Automatic Earth website. Nicole Foss (also interviewed by Mr. Kunstler) contributed to this one:

* Hold no debt.

* Hold cash and equivalents.

* Dont trust banks.

* Sell off real estate, bonds, commodities, collectables.

* Gain control over the necessities of your own existence. (That's the goal, but you'd probably have to become a hunter-gather to really achieve it).

* Work with others.

* Try to stay employed.

* Look after your health.

These lists are probably a good overview of the current thinking on opting out. Some of it is self-evident. Some of it is luck (climate change will make agriculture difficult or impossible in some places). But it's a place to start so you can at least be aware of the personal contraction that will eventually be forced on all of us. I believe this is a hard reality we are facing, but it need not be all gloom.

Among the items we sold at the garage sale were three guitars, a keyboard, and an electric piano, all left over from our sons' childhood musical training. A family from a rural area that did musical performances in churches took great interest in the guitars. A lady who played church piano was just as interested in the keyboard. As they all checked out the instruments they struck up a jam session of church music that brought other shoppers and us together in a moment of appreciative goodwill. It was a picture of "regular" people caught in the day's economic maelstrom--we needed to have a garage sale and they needed to buy from a garage sale.

For a short while, we forgot about buying-and-selling and just enjoyed a little music.

* * *

James Kunstler's interview with Charles Hugh Smith is here.

James Kunstler's interview with Steve Ludlum is here.

James Kunstler's interview with Nicole Foss is here.

Published on June 03, 2013 19:15

May 19, 2013

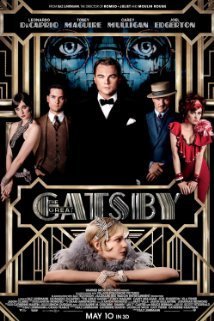

mr. gatsby's pool man

Among the works cited to be studied by anyone with novelist ambitions,

The Great Gatsby

is most always near the top of the list. It is considered the paragon of modern novel-writing in terms of construction--plot, characterizations, theme, symbolic imagery, etc. I have to confess, I've never read the book but I've read a lot about it and recently saw the new movie version starring Leonardo DeCaprio and Tobey Maguire.

Among the works cited to be studied by anyone with novelist ambitions,

The Great Gatsby

is most always near the top of the list. It is considered the paragon of modern novel-writing in terms of construction--plot, characterizations, theme, symbolic imagery, etc. I have to confess, I've never read the book but I've read a lot about it and recently saw the new movie version starring Leonardo DeCaprio and Tobey Maguire. The movie production struck me as excellent and my son (who did read the book) thought it followed Fitzgerald's story very well. It was my first introduction to the story and I can see why it's a classic. It certainly has relevance being set in the 1920s when income inequality was at levels comparable to today and fueled by stock market speculations (bubbles). At the level of the elites, that speculation was gambling just as it is today. A large source of the money they used seemed to come from alcohol bootlegging (prohibition of liquor sales being the law of the land) and the story implies that. It was a time of tremendous fun for "the rich" that only lasted about a decade before the mother of all economic corrections cut the party short.

The obscene display of wealth by the wealthy at that time is a central image in the story. The movie really brings this out. Gatsby's house is a castle and the exterior scenes around it are shot from the ground looking up. Even the interior shots are filled with architectural height and immensity. This says the rich are giants among us and is further emphasized with scenes of Nick Carroway's little gatekeeper's cottage next door to Gatsby's castle (literally in its shadow). These scenes are always looking up from Carroway's cottage or looking down from Gatsby's castle. The distance between them is apparent so we have a visual representation of the gulf that Carroway and Gatsby's friendship must span. This gulf is what was most interesting to me in watching the movie.

Life at the great homes depicted was supported by an army of servants. Dressed immaculately (in keeping with house decor), they opened doors, waited tables, ferried champagne and snacks to guests, fetched and carried and generally did anything their masters didn't want to be bothered with. There were often servants just standing at attention, stiff backed, holding a tray and waiting for orders to do something. I wonder how much these servants were paid. Was their typical day to get dressed up, go take their station in Mr. Gatsby's house, and wait for him to tell them to get him a glass of water? Or stand by a door until Mr. Gatsby or a guest looked to be wanting to go through it, so they could open it? (There's a great scene where servants are tripping over each other to open doors for a group of the rich who were arguing and storming in and out of rooms).

This is an image of mice scurrying about and making their living among the feet of dinosaurs. They survive by just doing their jobs. They may believe they are working for their "betters," or maybe just doing what they must to make a living. Some even take pride in what they do. There was one scene where a worker tells Gatsby the pool needs cleaning and he'd like to do it today. The man is not concerned with Gatsby's affairs or impressed with his huge parties. He just knows how to take care of a pool and wants to do his job. Gatsby tells him to do it tomorrow.

I think this scenelet of the pool man on Mr. Gatsby's estate is an image of American workers. Our living is facilitated by environments and situations created by the affairs of the elite who don't need jobs. We are only useful widgets to them and they give no thought to us beyond the little things they need for us to do. Perhaps we understand that perspective and just do our little jobs to make our livings. Perhaps we do our jobs with pride and take satisfaction from working them for our own sakes, irrespective of what our employers think. Perhaps we inflate our jobs and positions in our minds to levels of importance that make it more bearable for us. This would be the pool man imagining that Mr. Gatsby's main concern is his pool and that he couldn't conduct all his important business or maintain his wealth without a properly functioning pool, as provided by the pool man's work.

Perhaps most of us are like the deluded pool man. Perhaps a very few of us find a moment of clarity and walk off the job.

Published on May 19, 2013 10:02