Cathy O'Dowd's Blog, page 3

August 30, 2016

Skiing Into Mordor – an ascent of Mount Logan

The plateau. Despite the innocuous name, by the time we’d settled in to camp 4 it had acquired all the menace of Mordor. The Prospector col, the point of entry which sat just 250 metres above us, was the gateway into that frozen hell. The question rebounding slowly between our two tents as we cowered under an onslaught of wind and snow, was whether we were prepared to pass through that gate.

Mount Logan is not one of world’s iconic mountains. The Canadians we met seemed unaware that it is the highest peak in their country, and the second highest in North America. Our first sighting came from the window of a Helio Courier, a sardine can of a wheel/ski plane that can carry two passengers and kit per flight, all weighed beforehand. With a distance of some 100 miles to cover, we had time to boggle at the vast glaciers, flowing down from the biggest icefield in the world, outside of the polar regions.

We flew alongside the enormous slab of mountain, the highest point barely distinguishable from other peaks on the massif. The plateau towered over us at 5000 metres, with its notoriously complex ridges tumbling down the sheer sides. The plane swung round the end of the massif and our route – the Kings Trench – slid into view. It is as prosaic as it sounds, a long snow ramp hemmed in by high ridges, the only reasonably easy access to the plateau.

Logan may be immensely broad, the largest non-volcanic mountain massif in the world, but that doesn’t mean it’s small. We faced a 3,200 metre climb and given the distance, the height, the fickle weather and the need to acclimatise, we had to move double loads. We would carry food and fuel to the site of the next camp, bury it in the snow, and ski back down. The next day (or when weather allowed) we’d pack up camp and move it all up to the cache.

Two camps got us to the Kings Col at 4,100 metres, where the trench swings left and suddenly rears up in a short icefall. Teams ahead of us had already found a way through and a heavy snow year meant the crevasses were well covered. We were becoming adept at cutting blocks of snow to build walls to protect our tents from wind. The icefall featured the same clean-cut blocks, only this time the size of small apartment blocks, with crevasses between them that dropped down through ever-deepening shades of blue into inky darkness. We did three carries through the icefall, the terrain was too steep to battle with towing a sled. Each time we slid gingerly, breath held, under a vast curling wave of snow like the edge of a gigantic shell.

Above the icefall the angle eased a little. We used the sleds again, but now they hung behind us like sulky deadweights, sliding sideways on every zig-zag. We climbed up to the camp 3 on a day of relentless heat, I felt slower and weaker with each shuffle of a ski, my sled a recalcitrant demon from the lower reaches of hell. The reward that made it all worthwhile was the opening of the view, across the broad Seward glacier to the picturesque Mount Saint Elias and the Pacific ocean beyond. The glaciers were so vast they looked like a cloudscape seen from above, with the mountains poking through.

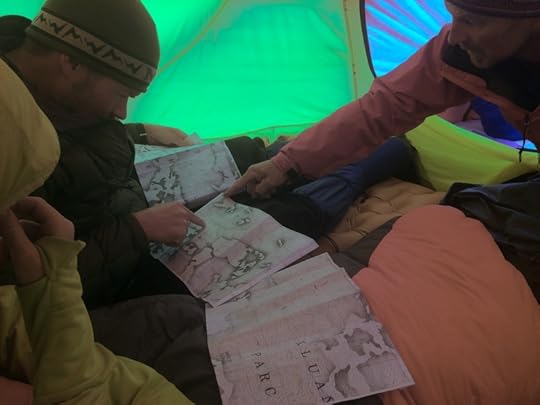

By the time we were huddled together in camp 4 (5245m) we had already covered over 18 kilometres (60 kms with the repeat carries). We peered at our sketchy topo maps, contemplating the sad truth that the Kings Trench dumped us at the wrong end of the notorious plateau. Calling it a plateau doesn’t do it justice. We needed to drop down 500 vertical metres from the col, and travel 12 kilometres to the summit while climbing up over 800 vertical metres. The coldest temperature ever recorded outside of Antarctica was observed on the plateau of Logan, -77.5 °C late in the month of May.

Part of the attraction of Logan is that even the non-technical Kings Trench route does not have a very high success rate, or many ascents. Denali now hosts over a thousand climbers each year, while Logan still has less than hundred.

As we’d dug ourselves a tent platform, we had watched two demoralised teams ski down past us. One local team, who had taken it very slowly due to three past failures, finally ran out of motivation. Then a pair of Austrians staggered into view over the notorious col, exhausted and disheartened after three days of bad weather and illness on the plateau.

We’d already benefited from the failure of yet another team, stopped by altitude sickness. They had bequeathed us an impressive cache of food and fuel, conveniently left at 4800 metres. It had included an array of expensive cheeses from the Whitehorse deli.

We were lucky enough to have a meteo professional from Vancouver supplying custom weather reports, received on our Delorme Inreaches (a two-way satellite text device). We wanted as a three-day window but a series of fronts were passing by, making the weather unsettled and very hard to forecast.

We’d had a team meeting while still safely down on the valley floor, and everyone was here to have a good time and come home safely. We all agreed, given the exposed nature of the plateau and the difficulty of exiting from it, that we’d only venture up there in reasonable weather.

However, as we waited and debated in camp 4, it become apparent that we didn’t all mean the same thing by ‘reasonable’. For Phil, reasonable meant perfect – no wind, blue skies – and with no sign of any such window, he wanted to go down. For others of us, buoyed by our success in getting this far, resignedly accepting that no ideal weather window lay in our future, reasonable expanded to mean whatever wasn’t awful.

We had all come a long way and invested a lot of time, money and effort, giving up other things to do this. We were climbing with two three-man tents, two GPSs, two Inreaches, two stoves. We had the capacity to split the team but one person could not safely descend on their own. Finally Chris, tired of cold and altitude, decided to go down as well.

The rest of us pushed quickly up and over the col, making use of a slender gap of better weather. Mordor opened up to us with a pleasant ski down into a low bowl, deceptively benign in a gentle wash of sunshine.

Exasperated with lugging loads, we camped early at the base of the direct line to the West Peak of Logan. A 4am alarm had us on the move by 7am. With four people squeezed into the three-man tent, there was little room to manoeuvre.

A clear dawn greeted us but the forecast predicted clouds moving in around 1pm. We were racing the weather to the summit, just racing very slowly. The winds rose as we shuffled our way higher. By the time we dumped our skis at 5850m and swopped to crampons, the mist had enveloped us. We trudged along the narrow ridge to the top at 5959 metres, buffeted by ever stronger winds, catching just the barest glimpses of the last few metres of the notorious Hummingbird ridge. It was a frustrating summit, without views, too cold to stay long – a poor recompense for the many days of work.

Once back on our skis, we found the cloud had swallowed up all signs of our track, the slope, and the mountain. Progress slowed to a wobbly snow-plough, the GPS used to work out a bearing along our up track, the compass used to follow that bearing. The hard-edge, ice-topped sastrugi, undetectable in the greyness, caught at ski edges poorly controlled by thighs shaking with fatigue. And then we faced a heart-breaking 200 metre climb over two kilometres, peering wishfully into the mist, convinced every shadow must be our camp. We collapsed into our tent nearly twelve hours after we left.

The next morning’s climb back to the col was tortuous. To say it was only 300 vertical metres over three kilometres does not begin to do it justice. Finally it ended and we fled back over the col, escaping safely through the gates of hell and making sure not to look back.

Joint ESC-ASC expedition

Dates on mountain: 8 to 27 May 2016

April 4, 2016

Best Foot Forward: the future of hiking

Re-invention of Hiking panel at the 9th World Congress Snow & Mountain Tourism.

Recently, I gave the opening speech and then chaired the Re-invention of Hiking panel at the 9th World Congress Snow & Mountain Tourism, held in my home country of Andorra. Below you will find the video of my speech and the full slide-deck of the presentation.

In summary, I concluded that short-term trends are favouring the hiking industry, but long-terms trends are not.

The outdoor market is growing rapidly and hiking is both a gateway to more extreme sports, and the activity people return to with age. Research tells us hiking is good for physical and mental health. The core of the market is white, wealthy and older, and that demographic is growing.

However, the outdoor market is changing and the ways the industry markets itself needs to change as well. Traditional websites and outdoor media have less impact than before. Social media is on the rise, particularly outdoors stars on Instagram. Hiking clients want connectivity to share their experiences and they want enhances products, customised to niche interests.

Long-term trends are troubling. Urban living is relentlessly on the rise. Most outdoor lovers take to the activity when young and children now spend less and less time outdoors. Dogs get walked in the park more often than children do. Virtual reality has just begun to recreate the outdoors, providing the drama without the effort. Media portrays popular tourist areas as badly overcrowded – from Everest to Machu Picchu, and the real growth in numbers is doing environmental damage.

So how can the market effectively be expanded? At its heart the commericial hiking clientele are white and middle class. Language and cultural barriers lead to providers concentrating on the core market. Innovative initiatives are needed to break through those barriers. Demographics that are traditionally dismissed as ‘uninterested’ in hiking need to be included, primarily by finding ambassadors within those groups.

The hiking industry has huge potential for growth but it lacks a united vision and a customer focus. The industry needs to do more to promote their cause with a unified voice and to reach out to new demographics.

Much of the key research referenced in the speech came from a fascinating report produced by Sport England and the Outdoor Industries Association, exploring the outdoors sport, activity and recreation market in England.

Re-invention of the hiking industry, 9th World Congress Snow & Mountain Tourism from Cathy O'Dowd

The post Best Foot Forward: the future of hiking appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

February 22, 2016

The art of focus – Ski the gaps, not the trees!

I’m delighted to present the first in a monthly series of blog posts, written in collaboration with Sarah Fenwick, record-setting extreme sportswoman, Chartered Sport Psychologist, Master Executive Coach, and leadership consultant to corporates and adventurers. We will be exploring the psychology behind some of the lessons we learn through adventure. Today – how to focus on the success you want, rather than the obstacles in your way.

“Ski the gaps, not the trees.”

That always seemed to be one of the silliest pieces of advice I was given as a novice skier. Let’s get real here. I might face-plant in the powder of the gaps and fill my goggles with snow, but the gaps aren’t going to hurt me. Those trees, though…..

Those trees are evil. I may not be an irresistible force on skis but those trees are undoubtedly immovable objects. When you run into them at speed, it hurts!

“The skis will go where you look.” That was also clearly nonsense. I’ve had my two skis abruptly part ways and head in two entirely different directions, neither one where I was looking, and the results weren’t pretty.

I learnt to ski as an adult and it was a slow, awkward process, driven by conscious learning rather than the intuitive discovery of children. With time, I came to realise that some advice only applies once you are good enough to use it.

Gradually, my ski control became a sub-conscious process, my body learnt to make the fine, intuitive adjustments faster than I could deliberately think them through and it became true that the skis would go where I focused. I started to see that if you skied down a slope staring straight at a tree, you’d ski into it.

Nevertheless, I certainly wasn’t going to ski through a forest without keeping a wary eye on where exactly those trees were. It still hurt to run into them! The challenge was to see how far I could push the tree into my peripheral vision while still having a beady eye on it.

The result was a series of heart-stopping near misses. Somehow the tree would sidle imperceptibly towards me and then abruptly leap into my path, resulting in a frantic swerve, a high-speed wobble and probably a crash into a snow-drift.

Finally it dawned on me that the truth was simple: you get what you focus on. A tree in my peripheral vision was still a tree I was obsessed with, afraid of – drawing my attention away from where I actually wanted to go.

I’m not suggesting you ski into a forest without taking an overview – a rapid mental snapshot of the nature of trees, the depth of the snow, the angle of the slope. At that moment I identify the obstacles I need to avoid and plot the line of gaps that will carry me safely through.

But once I’ve committed to the descent, then I need to let go of all the possible problems and give my full attention to success – focus on the gaps, one leading to the next and the next, slide my way through in an exhilarating fast dance to where the slopes open up below.

Ski the gaps, not the trees. Focus on what you want, not on what might stop you. It turns out to be very good advice.

The art of focus. Skiing beautiful powder through the Rialb forest in Andorra, my winter backyard. Skier: Curig, photo: Cathy O’Dowd.

Sarah Fenwick shares the psychology behind my experiences, and tools to help us all focus on success.

Have you ever had one of those ‘I got what I focused on’ moments? I know I’ve had plenty, and I’m sure most readers will have their own experiences of that realisation – whether you wanted it or not, you got what you got because that was where you’d placed your focus!

These experiences are sometimes referred to as ‘self-fulfilling prophecies’. We have an uncanny knack of expecting something to happen, usually based on our beliefs, and then behaving in a such way that our expectations become reality. We’ve proved our beliefs to be right and so we’ve further strengthened them. This is all well and good when it is a positive belief or expectation. However if our focus is based on a negative or limiting belief we may well get exactly what we don’t want.

When Cathy enters the tree thinking ‘if I hit a tree I’ll hurt myself ‘ or ‘there are so many trees it’s difficult to ski my way round them’, she finds the trees have a knack of leaping into her path…… and her belief that they are difficult to ski is confirmed.

When she switches her focus to ‘ski the gaps’ with the expectation that they will carry her safely through, she’s challenging that previously held ‘limiting belief’. By focusing on directing her skis where she wants to go, she enjoys an ‘exhilarating fast dance’ through the trees, a positive, self-affirming experience. With each successful experience, she reinforces a new ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ where ‘one gap leads to the next’.

10 steps for creating self-fulfilling prophecies that will focus you towards success in work, leisure and sport:

Identify what you want to achieve and how you will know you’ve achieved it.

Notice when your limiting beliefs or self-fulfilling prophecies occur and hold you back – what triggers them? Note down your limiting beliefs.

Replace the limiting beliefs with ‘believable and achievable’ positive beliefs that focus on what you want to achieve.

Think about and vividly imagine what success would look and feel like.

Look for and collect evidence (e.g. past successes) to support these new positive beliefs

Develop new self-talk phrases to support these new positive beliefs.

Before any potential ‘trigger’ situations connect with your new positive beliefs, feelings and self-talk.

Enjoy achieving – remember how good it feels.

Practice, practice, practice.

Decide how you will stretch yourself even further

Find more from Sarah Fenwick on her website, Twitter or LinkedIn.

The post The art of focus – Ski the gaps, not the trees! appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

February 7, 2016

The Art and Joy of Serendipity

Mountain climbing would seem to be the ultimate goal-driven activity, everything resting on reaching the top. The higher the peak, the more valued the achievement! By that definition, Everest should be the most important thing I’ve ever done. But it’s not.

I’m glad I did it, it was a fascinating experience in all its controversial complexity, but that kind of goal-achievement is not my main interest. As I wandered through the mountains of the southern French Alps recently, I was reminded once again that the thing that brings me the most joy in the wilderness is serendipity.

The word serendipity has as suitably exotic origin, having been created by Horace Walpole in 1754. He was inspired by the Persian fairy tale of The Three Princes of Serendip, the princes had the fortunate habit of “always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of”.

Discovering things we did not know we were looking for is deeply satisfying. One of my favourite climbing trips of all time involved my utter failure to climb The Nose on El Capitan. Long before El Capitan became an operating system, it was the iconic granite monolith whose smooth face, nearly a vertical kilometre high, dominates the entrance to Yosemite valley in California. The Nose is the most famous of the many technical climbing routes that inch their way precariously up the imposing wall.

Like many climbers from around the globe, for years I had dreamed of scaling the face, inching my way up the soaring crack-lines over a period of days, sleeping hanging from the cliff in a portaledge, pulling up a self-contained world of supplies behind me in a haulbag.

Finally the moment arrived. I was newly landed from Europe, my climbing partner had driven down from Seattle, the back of his pickup full of big-wall supplies. The time of year wasn’t ideal, late August was too hot, but it was what we could manage. We took only a day or two to warm-up on smaller walls (we had both climbed in Yosemite before) and then we headed out for the main event.

Looking up at The Nose on El Capitan from the valley, when it was still our big dream.

Three days into a five-day climb, we came to the conclusion we hated the entire thing. It was debilitatingly hot. We weren’t climbing fast enough. The haulbag, loaded down with badly needed water, was so heavy I couldn’t pull it up on my own. Instead of being a self-contained world that let us live on a vertical face, it was a Sisyphean nightmare – a burdensome beast from hell to be hauled up behind us – again and again and again.

The physical and mental freedom of rock climbing that I love so much, the feeling moving fluidly up the wall in a precise, ever-changing dance, had been replaced by a nightmare of demoralising logistics. We abandoned the dream, descended the wall in a series of long, exposed abseils, dragged the detested haulbag back to the pickup and wondered what to do instead.

A few hours later we were driving towards Nevada with a copy of the High Sierra Climbing guide from SuperTopo, which was full of long routes on some of the best alpine granite in the world, all of which could be done in one day. What followed was one of the best trips I have ever done. We started down south on the East Face of Mount Whitney and then the Fishhook Arete on Mount Russell. We moved on north via the Sunribbon and Moon Goddess Aretes on Temple Crag, picking off various other classics before finally arriving in Tuolome Meadows.

We drove to the road-heads, hiked in to remote lakes where we set up camp, and then spend long summer days climbing pitch after pitch of golden granite, returning to the comfort of the camp late in the afternoon. In-between high camps we dropped back to the Nevada desert and the comfort of king-sized beds, extravagant buffets and wifi from the road-side motels. Each excursion unfolded as a joyous surprise, the delight of discovering experiences we loved but had not planned.

Left: the Nose on El Capitan, centre: Michael belaying on Sun Ribbon Arete, right: Cathy following at Tuolumne Meadows

I’ve experienced the same joy on ski days in the backcountry, where we either have no plan or a plan that has turned out to be inappropriate given the conditions, and now we are reframing objectives on the fly. We stand on top of a summit or ridge, look around us and say: “let’s go that way! Maybe we’ll be able to climb our way out. Maybe there’ll be a gully we can ski down on the far side. We can retrace our steps if we have to.”

More often than not, we find a way through – an unexpected portal into another world, an unforeseen landscape opening out in front of us, abundant with new possibilities. Days like that and trips like that fill me with joy – the pleasure of unexpected opportunities grasped with commitment and enthusiasm, leading to discoveries we “were not in quest of”.

The chance is an event, serendipity a capacity.

Serendipity is not just about blind luck. The key to Walpole’s definition lies in the word he carefully pairs with “accident”, which is “sagacity”. Dictionary.com defines it as “acuteness of mental discernment and soundness of judgment”. Our luck in wandering up the airy granite ridge of the High Sierra or plunging down the sparkling powder fields hidden deep in the Pyrenees does not come out of the void.

It’s founded in a deep base of experience and training, that lets us make apparently whimsical decisions in remote environments. It lets us take seemingly unconnected pieces of information and put them together in ways that create a productive course of action.

To quote from the Wikipedia entry for serendipity: “Innovations presented as examples of serendipity have an important characteristic: they were made by individuals able to ‘see bridges where others saw holes’ and connect events creatively, based on the perception of a significant link.

The chance is an event, serendipity a capacity.”

We build that capacity by seeking out new skills that widen our abilities and by trying out experiences that led to both success and failure. It is in failing that we find where our limits seem to be and what our weaknesses are, but we will only make those discoveries if we take the time to think about why the failure occurred. And if we are prepared to risk failure in the first place.

A life guided by the joy of serendipity is not a life that is purposeless or directionless. However, it is a life that is guided more the accumulation of skills and the gaining of experience than by the setting of goals. We can turn our skills to a specific goal and experience the satisfaction of a plan well prepared and well executed. Or we can embrace the creative reinterpretation of chance, using our skills to turn accident into opportunity.

Various magical places from our High Sierras trip.

“Vital lives are about action. You can’t feel warmth unless you create it,

can’t feel delight unless you play, can’t know serendipity unless you risk.”

– Joan Erickson

Two interesting articles about serendipity in business:

The New York Times opened 2016 by sharing the story of the birth of the throwable video camera and pondering how we can increase access to serendipitous opportunities.

The New York Times opened 2016 by sharing the story of the birth of the throwable video camera and pondering how we can increase access to serendipitous opportunities.

Harvard Business Review: Frans Johansson reveals how his ‘brilliant’ book promotion strategy was born out of serendipity and wonders “What if all of the well-planned and well-executed “strategies” people have told us about are really the result of unplanned meetings and encounters, random moments and events, serendipity and plain luck?”

Harvard Business Review: Frans Johansson reveals how his ‘brilliant’ book promotion strategy was born out of serendipity and wonders “What if all of the well-planned and well-executed “strategies” people have told us about are really the result of unplanned meetings and encounters, random moments and events, serendipity and plain luck?”

The post The Art and Joy of Serendipity appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

January 5, 2016

What is holding you back? Time to use your feet!

With snow still sadly sparse in the Pyrenees, I found myself out rock climbing with friends on New Year’s Day. We stood around at the base of the cliff, talking about New Year’s Resolutions, trading the numbers we hope to achieve in 2016. I committed publicly to a nice big number but I have to admit that privately I was already doubting myself, thinking that I’ve made that commitment before – and failed before. So what is holding me back?

I often look to mountain sports for ideas I can apply to other areas, both in my work and my personal life. That moment of private doubt got me thinking again about one of the key pieces of advice that any rock climber is given when they start out.

Use your feet!

Rock climbing – which means scaling steep rock walls, clinging on by your fingers, rather than heading up to the summits of mountains – is in its essence aspirational. We are literally reaching upwards. We walk along the base of a wall of rock looking at various options. In a developed sport climbing area each possible route will have a name, possibly some information about the nature of the challenge and a grade of difficulty. Once you’ve selected a route, you begin, snaking your way up the wall like a lizard, eyes always looking towards the next set of moves, arms out above your head, hands running across the rock feeling for the next crack or edge that will aid your progress.

I see what appears to be the next good handhold, something I will be able to curl my fingers around securely, but it’s just out of reach. Or perhaps I can touch it, just, fingertips barely brushing the lip, but I can’t move up onto it.

The path I aspire to is stretching out ahead of me, I’m focused with relentless intensity on where I want to move to next – but it’s not happening.

My hands are beginning to sweat, making the rock feel slippery under my slick fingers. My forearms are beginning to tire, to reach that awful state we call ‘pump’, more evocative in French where they say “to have bottles for arms.” My muscles become a useless swollen lump, engorged with fatigue. My fingers are threatening to uncurl from their tenuous hold. Faced with the fear of the imminent fall, my legs begin to tremble uncontrollably.

Still I strain upwards, desperately fixated on that next hold just out of reach, the thing I’m convinced will save me, the hold I hope is a thank-god bucket. Everything in our culture tells us to look forward, reach upwards, eye on the prize, visualise the path to success, shoot for the moon. No day is more imbued with this vision that the first of the new year, when we embark on that cultural ritual of the New Year’s Resolution.

Somewhere far below me, the friend who is holding my rope is shouting upwards. Through the fear and fatigue I barely register the words: use your feet.

Sometimes we need to look away from the goal and look down at what is holding us back.

There are climbers who have the core strength and flexibility to put a foot onto a hold above their waist and then rock their weight up onto it. That will push you ahead fast, but your average climber is unlikely to have the skill or the energy to pull that off. We need to hunt for the small wins. I need to look back down at the rock I’ve already passed and remember that my feet still have to travel through that terrain. What am I missing? What did I hold onto with my hands that can now be repurposed as a foothold?

Feet lack the subtle ability of fingers, able to twist and curl, to separate and oppose. But they have their own magic. Tightly clad in the sticky rubber of a climbing shoe, aided by the solidity of well-placed body weight, a foot can smear onto the smallest sloping surface, a patch of rock just a shade less vertical than the wall around it. Or a foot can balance on a tiny ripple, no wider than the edge of coin. That can be enough to move my whole body up an inch or two, to let my questing fingers find the next handhold.

Sometimes I already have the handhold but it’s at full reach, my body elongated like a spring pulled apart to its furthest point, touching the prize but unable to use it because I have no stored energy in my body. No amount of hapless grasping with my fingers will change that. The other end of my spring needs to move up, to bring potential energy back into my system. My feet have to move.

Sometimes it doesn’t even need to be to a new foothold. It can be enough to shift from standing flat on the sole of my foot, to standing high on the tip of my toe. It can be enough to turn my foot on the hold, so that instead of turning me away from my goal, my foot pushes me towards it.

I am not a strong climber, I can barely do two pull-ups on the best of days. My arms do not perform well when swinging my entire body around. I need to be keeping as much of my weight as I can on my feet. Every time I feel stuck while trying to move upward, I try to remember to look away from my goal – the next handhold, the chain that hangs at the top of the climb – and look back down at my feet. What little gain can I make? What small ripple on the wall will win me a few more inches? How can a foot be realigned to be more efficient?

The win I gain is normally much more than just a few inches. If I am slightly higher, so my supple fingers can wrap around the next good hold, then I am suddenly free from the impasse. I can bring to bear all my strength and skill and experience, and move swiftly on upwards, finding new possibilities above me, as well as places to rest and recover from the fight I’ve now left far below.

In life as in climbing, when you find yourself stressed and stretched, straining towards a goal that seems just out of reach, what strength you have draining away in sweat and shaking – take your eye off the prize. Look away and look down. What is holding you back? Is there a trailing foot hanging too far below you? Or not helping to bear your body weight? Is there a small adjustment in where or how a foot is placed that will then let you stretch that much further above you?

In a world that puts so much focus on looking forward, it’s worth taking some time to look inward. When you can’t quite grasp what you are reaching for, try something different. Look away from the goal. Spend some time on the mundane detail. What is holding you back? What small changes can you make that will extend your reach?

Use your feet.

The post What is holding you back? Time to use your feet! appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

May 5, 2015

Risks too big to comprehend

“No climber ever expects to be in this position. When I was planning Lhotse, the word “earthquake” never entered my mind.” From Alan Arnette’s blog.

I’ve been on Everest four times, and on Lhotse once. During all those expeditions, the risk of earthquake never once occurred to me or my companions. I’m not sure what the risk management strategy would be. Run away? You aren’t going to get far.

This powerful video of the avalanche that was triggered by Nepal’s 7.8 magnitude earthquake and struck Everest base camp shows just how futile running away would be.

Last August I was ski-touring in the lakes region of northern Patagonia. The last summit of our trip was the iconic volcano of Orsono, and to the south of us lay another pretty volcano with its skirts of deep green forest and shirt of pristine white snow – Chalbuco.

After decades of inactivity, with no warning noticed by local monitors, Chalbuco erupted twice on 22-23 April of this year, sending a huge column of lava and ash several kilometres into the air and causing the authorities to declare a red alert and evacuate more than 4,000 people.

[image error]

Left: my photo of Chalbuco from Osorno. Right: A APF/Getty image of Chalbuco erupting, with Osorno visible on the left.

Dave and I knew we were skiing on live volcanoes. One village we departed from had volcano evacuation route signs prominently displayed. We laughed and photographed them and kept going. What to do if the thing actually erupted never featured in our safety plans. I guess we assumed someone somewhere with some authority would have some idea it was coming and warn us off.

Beyond that we’d take our chances. As individual adventurers heading into environments encompassing a range of risks, the best we can do is have a general safety plan in place – for medical treatment, for communication, for evacuation – a plan that hopefully covers any of the many ways in which adventure can go wrong, even the ones we haven’t thought of.

The safety conscious might wag their fingers and say we should have stayed at home. (And indeed, on Alan’s blog is a long debate on whether the climbers on Everest ‘deserved’ helicopter evacuation after the earthquake – a debate so mired in colonialism and white guilt and first world wealth and commercial-vs-‘real’-climber judgements that it’s hard to pick your way through it.)

But how safe is it at home?

How many people do you think live within 100 kilometres of a fault capable of generating a magnitude-7 (or stronger) earthquake? (To give scale to this, Everest was about 160 km from the epicentre of Nepal’s earthquake.)

The answer is an astonishing 250 million people.

[image error]

The plot shows the total population since 1950 of “developing” and “developed” cities that are located within 100 km of a fault capable of generating an earthquake with M ≥7. (Tucker 2013). Sourced from VOX http://www.vox.com/2015/4/27/8501281/...

And if this is the reality of your home, then risk management needs to be handled much more specifically.

It was no secret that Nepal was ill-prepared. It was known the most buildings would not withstand an earthquake, indeed most of them didn’t even comply with the building code that Nepal did have in place. It was known that Nepal lacked a disaster protocol. A week before the earthquake some 50 experts assembled in Nepal to discuss just these problems.

It is an axiom of earthquake management that (the odd avalanche aside) earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings kill people. In 2010 two similar earthquakes hit Chile and Haiti. “Only about 0.1 percent of Chileans affected by the 8.8-magnitude earthquake died. By contrast, 11 percent of Haitians affected by a 7.0-magnitude earthquake with similar shaking died.”

Why? Because the 9.5-magnitude earthquake that struck Chile in 1960 had left earthquake-preparedness front and centre in national and government consciousness.

What is it about earthquakes that leads mankind to often ignore this particular risk? It seems to be more than just rarity – earthquakes are actually fairly common and are visually dramatic, so they tend to feature in the world-wide news cycle. From 2000 to 2010 there were 22 earthquakes of magnitude 6 or greater.

In 2013 Brian Tucker, founder of GeoHazards International, published an important paper about this in Science. His paper is subscription only but VOX picked out some of his key ideas.

Often, Tucker points out, it’s a funding problem, particularly for poorer countries. Upgrading buildings is expensive, after all. In some cases, there might be unique obstacles at work (in Nepal, civil unrest made the task of retrofitting even harder). But in many areas, the biggest barriers appear to be psychological — people aren’t even thinking about preparing for earthquakes.

“The psychological reasons we don’t prepare for earthquakes are often ignored,” says Tucker. “Just as an example, we still find a lot of people who think of earthquakes solely as an act of God, and don’t think about the very real ways to reduce risks.”

I’m a believer in ‘acts of God’, in the sense that I think we are too quick to assume that every accident must be blamed on someone and that every risk must be avoidable. As individual adventurers passing for short periods through high risk environments, I feel a general protocol for disaster preparedness is the best we can do. Nevertheless, just researching this post has challenged my own assumptions about risk preparedness.

Individual adventurers aside, as societies permanently settled in risky environments, with access to both information and solutions, we can and must do better in protecting ourselves and our citizens.

Support MITRA Music for Nepal, my initiative with Anni Hogan to raise funds for reconstruction in Nepal.

Like us on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/MitraMusicForNepal and follow us on Twitter @Music4Nepal

The post Risks too big to comprehend appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

April 10, 2015

Why to make it up as you go along

The difference between ‘fluid decision-making’ and ‘making it up as you go along’ can be hard to detect. I’ve just returned home after a nine-day ski-tour in the Ecrins, a spectacular block of mountains in the southern French Alps. It was an Eagle Ski Club tour and there was a day-by-day plan. Not only did we not do a single thing on that plan, we altered the plan and then re-altered it on a daily basis for six consecutive days. Is that a sign of success or of failure?

It was an interesting exercise in peer-driven decision-making. Our group had an official ‘leader’, Alain, who had organised the trip. But in terms of expertise, no one person was obviously the expert. Alain had skied at La Grave (the local off-piste ski resort) and had done the planning, so had the most local knowledge. Two of our party of six spoke French and so had best access to local weather reports and information from other skiers and hut guardians. I had the most high mountain experience, thanks to my various Himalayan climbs. Tom was the best skier, being a BASI3 ski instructor. All of us had done independent (without a guide) ski-touring. None of us had toured in the Ecrins. And on top of all that, given that our goal was to keep the group together, and to travel safely, it had to be the most conservative voice that dominated in any group decision, not the most expert.

The Ecrins are a complicated mountain landscape – relatively flat valley floors lead into a world of steep-sided valleys and sweeping walls of crenellated rock with narrow passes of snow giving access from one valley to another. There is little in the way of safe, gentle terrain. In addition, we were in the middle of a weather system of howling wind, over 60 km/h and gusting over 80. Such strong winds make it difficult for a skier to stand when high on a mountain or crossing a col, if you are knocked off your feet, sliding for hundreds of meters down icy snow slopes or over rock-bands is a distinct possibility.

High winds batter our ski group as we climb.

Even more deadly is the unseen consequence of wind – it is damaging the snow. The crystalline snowflakes are battered down into more uniform shapes that fuse together in slabs, slabs that are impossible to detect in the general snow-scape but that can be broken loose by the weight of a single skier. And when a slab tears away from the snow around it, it starts an avalanche.

The risk of this is not an exaggeration. Three days into the tour, our latest new plan (having already changed the plan due to poor visibility) involved crossing the Col Émile Pic to reach the Refuge des Écrins. With the wind continuing to howl, we were wary of dealing with the abseil required to drop down from the 3483 metre col and we decided to continue up the Plate de Agneaux glacier valley to the Refuge Adele Planchard instead. We passed three other ski parties that chose to cross the Col Émile Pic – which of course left us wondering if we’d were just being overly cautious.

Two of those other parties descended safely to their mountain hut. The third one inadvertently triggered a windslab just below the abseil. Of the group of 12, eight were caught in the subsequent avalanche, three died and one was airlifted to hospital, gravely injured. The fact that they had two professional guides leading their group did not save them.

We heard the news that evening as it was passed by radio from one mountain hut to another. We already had another piece of sobering information. We had taken advantage of this one day of clear skies to climb our only summit of the week, La Grande Ruine, 3765m. We had battled through the high winds, and had made our own mistakes, with three skis – left below the summit when we continued on foot with iceaxes and crampons – being blown away. We eventually found all three thanks to good luck and the help of another ski group.

[image error]

Our group on the summit of La Grand Ruine.

We and two other groups skied down the hut and were safety seated in the dining room, drinking tea and waiting for dinner to be served, when a lone skier came down the slope we had all crossed a few hours earlier. He took a steeper line than we had and triggered a windslab. The subsequent avalanche took out a slope we had all skied across. He got himself out of the debris but lost a ski in the process. We promptly changed our plans yet again, pulled out of the main range altogether, and then slowly worked our way back in over the next few days as conditions improved.

[image error]

The avalanche track is outline. On the right a skiers is circled for scale. The arrows show our line of entry and exit – done before another skier triggered this same slope. The summit of La Grand Ruine is the snow triangle in the background.

One of the challenges of ski-touring with relation to avalanche danger is the lack of immediate feedback. In many ways mountains provide powerful real-time feedback. If you are caught by high winds, the feeling that you might be lifted off your feet is a visceral reminder that being in this place in these conditions is a stupid idea. But avalanche feedback is very one-sided. Once it has happened it is visually obvious and if you are caught, the consequences are immediate and profoundly serious, anything from lost skis, to grave trauma injuries, to death.

But every time we ski over a windslab that we can’t see, and we don’t trigger it – by chance we don’t pass over the hidden point of maximum weakness, where our own body weight can set off the hidden ‘land-mine’ that will cause the slope to collapse – we have no idea whether our safe passage was due to skilful choices or blind good luck. Being human, we tend to believe in our good judgement until another skier behind us triggers the slope and proves us wrong.

Mountains are a low expertise environment, in the sense that the cues and patterns we attempt to detect don’t automatically lead to reliable outcomes, both weather and snow conditions being frustratingly difficult to judge with repeatable accuracy. That makes it easy to mistake luck for subjective skill. We need to be constantly cautious, focusing on the consequences of failure in the decision making, always aware that our apparent skilful reading of the environment may in fact be no more than a run of luck.

Onlookers tend to assume that mountain climbing – whether on foot or on ski – is all about the ‘conquering’ of summits. And we did have the highest peak in the Ecrins on our plan, or at least the winter ski peak, the Dôme de Neige des Écrins, which tantalisingly just crosses the magic 4000 meter mark. It is a magnificent peak, visible from many kilometres away, and providing a exhilarating ski descent. But we abandoned it as an objective without a second thought. It was not in fact a key focus.

[image error]

The snow dome at the back right is the Dome de Neige des Ecrins, highest peak in the range reachable on skis. Tantalising, but out of reach for us given current conditions.

I think what allowed us to come away from the tour feeling that the whole thing was a great success, despite the constant plan changing, was having a shared agreement about what our real objectives were. They were not the Dôme de Neige des Écrins, or the initial plan for the tour. What we actually wanted was:

to enjoy and challenge ourselves

to explore the Ecrins range

to come home alive and uninjured.

We achieved all three, everyone left the tour excited about what we had done, keen to return to the Ecrins and happy to ski together in the future. It was an unqualified success and while our constant shifts of plan were a source of amusement, we were proud of how we’d dealt with the difficult conditions.

[image error]

A happy team of skiers having dinner on our final hut night.

Working in a high risk, high uncertainty environment requires maintaining a broad frame of reference. To fixate on the initial schedule or a specific peak leads to biased decision-making, entering a sub-conscious process of explaining away potential threats in order to allow the plan to unfold unhindered.

We have to constantly ask “what could go wrong in this scenario” as a way to test the relationship between the current plan and the overall priorities. On a daily – even hourly – basis, we need to pay attention to cues and patterns in our environment, and relate them back to our priorities. We can’t change our environment – other than by moving within it. We want to stay true to our priorities. So the thing that changes is what lies between them – our plan of execution.

We were not simply making it up as we went along. We stayed true to our three key objectives, by letting the plan and the specific summits slide away as conditions changed. Fluid decision-making, informed by the latest information, let us achieve what really mattered to us.

Thanks to Steve Suckling for providing some of the ideas that underly this post. Steve and I are currently collaborating to create a new product around risk management we plan to share with our clients this autumn.

The post Why to make it up as you go along appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

March 6, 2015

When past performance doesn’t predict future success

and why super-star hires can be an expensive mistake

In a culture that worships success, failed projects normally just sink out of sight, vanishing without explanation. One prematurely terminated adventure project recently caught my eye, because the honest analysis of the failure echoed my own experience from my first Everest expedition.

In summer of 2014 Brian Cunningham, a British explorer with fifty years of adventure experience, joined up with Jamie Young to attempt the first circumnavigation of Ireland in a sailing dinghy. Ten days into the project, it was over. Brian’s analysis of why was interesting. He identified two key problems. One was that he seriously underestimated the size of the challenge, and managed to ignore the weather information that pointed to how difficult it would be, cherry-picking from the data to support the story he already had in his head. But it was the other problem that interests me here.

“I seriously over-estimated my capabilities,” wrote Brian in the final blog post of the project. “I deluded myself into thinking that I could handle hours on end sailing a small dinghy in the open sea. At seventy-one I’ve discovered what most people had already concluded. Both physically and mentally I wasn’t strong enough, fit enough, flexible enough and agile enough the job.”

But his delusion was not pure hubris, he had evidence to back up his belief in himself. “My self-confidence had been artificially boosted by the 70@70 run I’d done to celebrate my seventieth year (A seventy mile solo run through the Scottish mountains in under 24 hours).”

The trouble was that that particular past performance had little bearing on the new challenge. “A hard day in the hills was no guide to how well I would stand up to six to eight weeks of continuous mental and physical strain in a sailing dinghy.”

When we look for something that will provide external validation for our choices, we commonly turn to past performance. We are strongly disposed to believe in trends – that what worked in the past will work in the future. And while not infallible, it is not a bad premise to work from.

However, finding ourselves dazzled by fancy resumes and performance records, we often fail to identify how a past success is different from our future needs. Business people and adventurers are both liable to fall into this trap.

In the first Everest expedition I was involved in, some local super-star climbers were considered automatic choices for the team, both by the expedition leader and by themselves. But no one stopped to consider that their experience was based in very small teams on highly technical but short-duration alpine-style climbs. And that their leadership style was haphazard – in a very small group you can arrange everything through a running conversation.

This expedition involved a raft of commercial sponsors, several hundred thousand dollars in budget, three months on a single mountain, climbing in traditional siege style, with a team too big to forgo structure and the project led by a man who had trained as a British army officer. Neither the objective nor the culture of team suited the super-stars and it all ended very badly indeed. (Explained in my book about my Everest expeditions, Just for the love of it.)

Boris Groysberg and Nitin Nohria from Harvard did some fascinating research into this idea with General Electric alumni. They explain that “When a company hires a CEO from General Electric—widely considered in the United States to be the top executive-training ground—the hiring company’s stock price spikes instantly.” They studied 20 former GE executives who were appointed chairman, CEO, or CEO designate at other companies and they found that human capital is not as transferrable as we might wish.

“Not all managers are equally suited to all business situations. The strategic skills required to control costs in the face of fierce price competition are not the same as those required to improve the top line in a rapidly growing business or balance investment against cash flow to survive in a highly cyclical business. Such skills are usually transferable to new environments—and are the most portable type of human capital other than general management skills—but they won’t offer an advantage if the strategic needs of the company don’t match the manager’s skills.”

When it comes to selecting new staff, or choosing members of an expedition team, all to often we seem to default to the question – what can they (the super-star hire) offer? In fact what we should be asking is what do we really need? I suspect we avoid doing this because working out what we will really need in the future is hard. The truth is that we can’t know for sure.

It is not just leaders that need to be realistic about the skills needed for their new projects. Individuals need to be self-aware about their talent set and seek out environments where they will thrive. The super-star climbers walking out on the Everest expedition nearly sunk the project. But the whole thing was also a waste of their time and energy, and a traumatising experience for everyone involved.

As Groysberg and Nohria point out, “When star executives switch companies, they leave an environment in which their skill sets allow them to be effective. The more closely the new environment matches the old, the greater the likelihood of success in the new position—a factor managers would do well to consider when deciding to change jobs.”

As project leaders, we need to consider the future with a ruthlessly pragmatic eye, honest about the skill sets that will be needed and the culture we want those skills to be operating in. On a climbing expedition you may be better off with a group of mid-level climbers who are aware that they need to cooperate to excel, and who are committed to a team ethic. The super-star climber is better off pursing their individual goal, with the help of a support crew who are clear about what their role is.

As individuals, if – like Brian did – we want to step outside the cliched ‘comfort zone’ and open ourselves to new challenges, we are well advised to only seek the new in certain aspects of the enterprise, while making sure that our current skill set, whether we are talking about native abilities or learnt skills, is of use to the overall objective.

It’s not about being (only) as good as our last success. It’s about finding that sweet spot where the sum of our past experiences intersects fruitfully with our future challenge.

The post When past performance doesn’t predict future success appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

January 16, 2015

When keeping it simple leads to stupid

Yesterday an infographic from BBC World swirled pass in my twitter feed, celebrating the first free ascent of the Dawn Wall on El Capitan, done by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson. It extolled their achievement of climbing “half a mile, straight up, without ropes”.

So clean, so catchy. So wrong.

[image error]

Twitter laughed at them and within five minutes they’d tweeted an amendment. “Ropes were used only for safety purposes not as climbing aid.” Who cares? say the non-climbers. Sounds cool, really impressive, bit mad, moving on. But we should care. Climbing without ropes is a specific thing, a thing called free solo. There is no one in the world good enough to free solo the Dawn Wall. Maybe there never will be. Or maybe the next generation will blow us away and do it.

In 1957 the first ascent of the classic route on El Capitan, The Nose, involved a siege aid climb over 45 days. Nearly fifty years later, In 2005, Tommy Cadwell free climbed The Nose (so still with safety ropes but not pulling on safety gear) in under 12 hours.

A while back, an executive at a corporate event where I was the motivational speaker, told me that his friend was “climbing all the mountains”. Really? That’s a lot of mountains.

“There are infinitely more unclimbed peaks than there are climbed ones,” Lindsay Griffin (British journalist and alpinist) once said to the BBC. He has climbed at least 65 previously unclimbed mountains himself, mostly in Central Asia and the Himalayas. “It’s a vast place, the world.”

We live in the world of the infographic and the bullet-point action plan. The 140 character tweet and the 30 second attention span. The idea of the information flood is part of our cultural discourse and we are constantly told to keep it short and snappy, simple and memorable. There is not a lot of room for vastness in a tweet.

By “all the mountains” my executive acquaintance meant the Seven Summits. Which is not the seven highest or the seven hardest. It is the highest mountain on each of the seven continents. Three of those are interesting, four rather less so. As they are climbed today, none is very difficult. The Second Seven (the second highest mountain on each continent) are much harder.

The biggest asset you need to ‘conquer’ the Seven Summits is money, the money to fly yourself from continent to continent and then hire the guides to escort you up the peaks.

[image error]

A rather lovely Seven Summits infographic from http://ffctn.com/

Every time we reduce the vast, varied world of mountains to a list of seven (which aren’t even the hard ones), every time we use “no ropes” as an inaccurate short-hand for the complex achievement of the Dawn Wall, we cut off our sense of a possible future. We lose the mountains that have never been climbed, we lose the possibilities of true rope-free solos. And then we complain that it’s all been done and there’s no real adventure left.

The simplicity of the infographic is great, if it’s an entry-way to the true depth and complexity of the subject, but not if it’s a substitute for it. The top-ten bullet list is a wonderful way to quickly convey information, but the creative way forward is likely to be found be digging around in the overlooked numbers 11 to 20 – and beyond.

“It’s a vast place, the world.” We do neither the world nor ourselves justice if we always prize simplicity and brevity over complexity and immensity.

This National Geographic article is one of the best I’ve seen for explaining the real significance of the Dawn Wall ascent to a non-climber. (Note all those ropes in the very first picture!)

The post When keeping it simple leads to stupid appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.

December 6, 2014

New softcover edition: Just For The Love Of It

I love ebooks. The idea that I can disappear for a week-long ski-tour or a two-month long Himalayan expedition and just tuck a Kindle into my rucksack, a device the size of a paperback that can contain a 1000 books, one for every mood and every occasion, recharged infrequently thanks to a solar panel and the rays of sun – that is just amazing! On Everest in 1996 I remember being stuck at camp 2 (6500 metres) for a week with nothing to read but Spike Milligan’s War Memoirs Vol II

into my rucksack, a device the size of a paperback that can contain a 1000 books, one for every mood and every occasion, recharged infrequently thanks to a solar panel and the rays of sun – that is just amazing! On Everest in 1996 I remember being stuck at camp 2 (6500 metres) for a week with nothing to read but Spike Milligan’s War Memoirs Vol II and Living Dangerously: The Autobiography of Ranulph Fiennes

and Living Dangerously: The Autobiography of Ranulph Fiennes . They are both very good books, but I’ll gladly never see either one again!

. They are both very good books, but I’ll gladly never see either one again!

When my book, Just For The Love Of It, reached the end of its final hardcover edition, I was content to let it live on in the electronic ether , but it turns out that not everyone is as delighted with the invention of the ebook as I am. Many readers are adamant about their attachment to the feel and smell of paper, the sheer physicality of a book is important to them. With those readers in mind I’ve released a new paperback edition of Just For The Love Of It

, but it turns out that not everyone is as delighted with the invention of the ebook as I am. Many readers are adamant about their attachment to the feel and smell of paper, the sheer physicality of a book is important to them. With those readers in mind I’ve released a new paperback edition of Just For The Love Of It , including the additional chapter covering my 2003 attempt to climb to a new route on the Kangshung Face, a story that is not in the old hardback edition. You can, as ever, order it from Amazon.

, including the additional chapter covering my 2003 attempt to climb to a new route on the Kangshung Face, a story that is not in the old hardback edition. You can, as ever, order it from Amazon.

Over the years people have said to me that they like the honesty of the book, particularly the emotional honesty. I’d write a rather different book now, if I returned to that time in my life, but the underlying impulse would be the same. I was sick of books with titles like The Death Zone and Killer Mountain. I love climbing, I climb for the joy of the activity. It can be frustrating and boring, difficult and frightening, but overall I climb for the love of it. Which was where the title of the book came from. If you really are hating every moment of your time on the slopes of some giant challenge – stop! Give it up. Go home. Do something else.

I wanted to write a book that shared the pleasure I get from wild mountain environments and ridiculous vertical challenges. I also wanted to share some of the emotional difficulty of these big expeditions. I live in the British cultural tradition and the British tend to produce a certain type of mountaineering book, generally written by a man. It prizes stoicism and understatement. The highest mountain in the world gets nicknamed The Big Hill. Edmund Hillary’s first words to his lifelong friend George Lowe, the first climber to meet him and Tenzing Norgay as they descended from the summit of Everest, were, “Well, George, we knocked the bastard off.” All difficulty must be downplayed, no emotions may be admitted to and any detailed talk can only be of tools and techniques.

This style is delightfully and hilariously parodied in the cult classic The Ascent Of Rum Doodle by W. E. Bowman. One of the books it is parodying is itself a truly great read, Annapurna: The First Conquest of an 8000-Metre Peak

by W. E. Bowman. One of the books it is parodying is itself a truly great read, Annapurna: The First Conquest of an 8000-Metre Peak by Maurice Herzog, the account of his 1950 expedition. The image of Herzog stoically amputating his toes while on the train across India and sweeping them out of the door when stopped at a station will never leave you! Hard men indeed.

by Maurice Herzog, the account of his 1950 expedition. The image of Herzog stoically amputating his toes while on the train across India and sweeping them out of the door when stopped at a station will never leave you! Hard men indeed.

However, you do not actually need to be that hard to climb Everest. The book that first suggested to me that there might be a place for people like me in the high Himalaya was another Annapurna classic, Annapurna: A Woman’s Place . The best-selling account of the 1978 ascent of Annapurna by the American Women’s Himalayan Expedition, it was a rare female perspective in a very macho world. Their team motto was A woman’s place is on the face. Well, why not?

. The best-selling account of the 1978 ascent of Annapurna by the American Women’s Himalayan Expedition, it was a rare female perspective in a very macho world. Their team motto was A woman’s place is on the face. Well, why not?

By the time I got back from the world’s highest mountain, the ‘Everest industry’ was just beginning to ramp up. I wanted to write something that was much more personal, more emotional, that gave an insight into the feelings engendered by clinging to the slopes of this giant peak, rather than the techniques needed to surmount it.

From the feedback that I have received from readers over the years, I seem to have succeeded, at least to some extent. Every year there are more women out in the mountains, and it’s a great thing to see. But it remains a world dominated by male voices, in blogs and books, tweets and films. I think there is still a place for a story that sets aside the stiff upper lip and shares the emotional complexity underneath.

“The story of what she choose to do will haunt everyone who reads it.” UK Daily Mail

“It truly was one of the top 5 best Everest books I have read and I have read nearly all of them.” Karl J. Landa

“Your descriptions of inner feelings. WOW! I climbed it with you.” Hal A Huggins

“Your book beautifully illustrates the fact that its an inner journey as much as it is an outer one…” Ziah Hayat

Grammarly, the grammar checker website, produced a fun infographic trying to argue that, despite the weight of hefty male voices in the literary world, women are actually better writers. I’m not sure that they are right, but in the male world of mountaineering, I do think that a woman’s voice can share different insights.

The post New softcover edition: Just For The Love Of It appeared first on Everest Climber & Motivational Speaker Cathy O’Dowd.