L.M. Browning's Blog, page 24

April 7, 2012

Homebound Takes Root in Stonington | An Article from The New London Day

By Suzanne Thompson

{Publishing April 7, 2012 in The Day for the article click here >>}

It's the name an aspiring teenage Stonington author wrote on her rough manuscripts 15 years ago: "Homebound Publications."

"It was just a hobby, an aspiration, it wasn't a reality," says Leslie Browning, who also goes by L.M. Browning.

That reality has come full circle for the 30-year-old, as both a recognized author of poetry and fiction and as founder of a new independent publishing company based in her hometown.

Browning was instrumental in launching Homebound Publishing in 2011 as an imprint of Hiraeth Press, a Boston-based publisher of nonfiction and poetry formed in 2006. She joined that company two years ago to learn the ropes of publishing and to work with kindred spirits in the genre of spiritual and mystical writings.

"I'd always wanted to open my own publishing house, but I was so intimidated by the process of applying for the business licenses and taking on something of that financial magnitude," says Browning, who in the past two years has been nominated for the respected Pushcart Prize for her poetry and for her first novel, completed last year. Her writings are shaped by her studies of world religions, nature and philosophy.

As a partner and co-lead editor of Hiraeth, she has been doing everything from reviewing incoming manuscripts and deciding if they should be published to shepherding books out into the market. When the opportunity came for her to take the reins of the new publishing house, she jumped at it and brought Homebound to Stonington.

"We call ourselves a contemplative publisher," says Browning. "We want to write books that will aid people in trying to find themselves and understand their place of belonging in the world now."

The publisher is releasing three books in its first year. Released yesterday is "The Crucifixion," by Theodore Richards, a poet, writer and religious philosopher. Homebound describes the book as a modern American myth, reclaiming the mythic patterns of Christianity, reframing the Old Testament in terms of the flight of African Americans from the Deep South during the Great Migration (1910-1970) as the struggle for meaning in the modern, urban America.

Richards's "Cosmosophia," published in 2011 by Hiraeth Press, won the Independent Publisher Awards Gold Medal in Religion. He is founder and executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a dean and lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary.

Homebound also will publish Browning's first full-length novel, "The Nameless Man," which she co-authored with her mother, Marianne Browning.

The book is a contemporary tale of 18 strangers traveling through the Holy Land. Forced to take refuge in Jerusalem during a militant attack, kept in close quarters in an abandoned building for four days, the group is challenged and transformed by a mysterious nameless man, a fellow traveler, who poses a revolutionary perspective on the age-old questions of love and evil, religion and god.

The third book, "The Sapphire Song," by Todd Erick Pedersen, is a tale of two young lovers, a visionary sculptor and a storyteller from a distant township. It also has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Although Homebound has chosen its three titles for this year, Browning says it is still open to submissions. It also produces "The Wayfarer," a biannual literary magazine of contemplative poetry and prose. Browning serves as executive editor.

"We're aiming for (publishing) six to eight titles a year," she says. "For a small, independent press, that's considered a lot. We could do more, but we would rather keep the quality up and choose only books that we're totally in love with."

Homebound is producing paperback and e-books, consciously mindful of its carbon footprint. Browning says it is going to great lengths to partner with printers who follow sustainable foresting practices. The publisher will make an annual donation to an ecological charity.

Locally, Homebound paperbacks are carried at Bank Square Books in Mystic and The Other Tiger in Westerly, R.I., as well as online.

Suzanne Thompson lives in Old Lyme. Catch her weekly radio show, "CT Outdoors," on WLIS 1420/Old Saybrook and WMRD 1150/Middletown. She can be reached at suzanne.s.thompson@sbcglobal.net.

April 4, 2012

The Paths We Walk | An Excerpt from The Nameless Man

An Excerpt from Chapter 17: The Convergence of The Nameless Man

"…The inner-dialogue at an end, his eyes opened—sharp, wide and clear. The room was quiet—no conversations, no war-cries, no debates. For once even Yoseph was in a deep sleep.

Rising quietly in the dark, drawing his shawl around him and taking his staff in-hand he closed the distance of the bare room and moved swiftly down the hall—rounding the stairs, moving down unto ground level and out into the still night air.

If I am here…. If this all can actually be resolved, then let it be so. I have lingered on in this death too long. Since that scarring day I have been alone—apart from you and from my family—isolated in my pain, grappling with the same ghosts, reliving the same moments and struggling against the same unchanging facts. I don't want to lose another day to this torment.

~

He moved silently through the night, passing along the narrow streets and underneath the arched doorways of the old city. In comparison to what it had once been, the city was unrecognizable. Small remnants of the ancient place looked familiar beneath the modern alterations, but they were few and far between. Thankfully he was not taking his directions from recognizable markers. His heart was leading him instinctively to the pivotal place—not the place recorded in history but the true place.

He could remember the city the way it was, in truth it was the one thing he could not forget. Much to his dislike, what took place here had been driven deeper than any other memory to occur in his life. The attack had become the center of his existence—above his family, above his children and above his own faith. His miraculous life, which could so easily be defined by his extraordinary communion with the divine and the immense love of his family, had come to revolve around the encounter with the evil he had in this place. This place had become the axis upon which his Being revolved and because of this, he had lost himself.

He had become his wounds. Long ago he had learned that the only way to regain himself once more was to heal the wounds. It was painfully ironic that, while others found his insights helpful, he could not heal himself. Clarity is so easily had when looking outward than when looking within. He understood the sufferings of others with such ease, finding the root of the pain that they could not; while the end of his own pain was ever-elusive.

For so many nights he had let the memories overwhelm him and rob him of his sleep. But on this night, he had crossed that line—moving beyond exhaustion to that point where he was too tired to let things go on how they had been; tired of cowering, tired of hiding, tired of begging within himself that nothing more happen.

Since that moment, on that infamous night all those years ago, when he stood before the council betrayed. Since that moment, he had been attempting to return to who he was before the attack—before they had come for him and the myths about him had been spun. He had trusted his heart back then—heeding his inner-voice in the face of death and torture. Yet at the same time, he could not help but think the man that he was then was only a child—unknowing and idealistic.

He wanted to again be who he once was yet, at the same time, he had come to hate who he was. Over the intervening years since the night when judgment was passed upon him, he had become his harshest accuser, blaming his own blindness as his downfall more so than the actions of those who betrayed him.

Haunted by regret and frayed by doubt, nothing had been certain in him since that night…since this city. Within the walls of this city he had lost himself. Would it be that within these walls he would find himself?

He felt words flow through him as he walked; it felt as though another walked with him, leading him down the path: We must believe in our healing if we are to allow ourselves to be healed. We must stop punishing ourselves if we are to escape our pain. We must place blame where it is due, whether upon ourselves or upon others and then we must accept that what has passed, cannot be changed. We mustn't live in regret. We must be ever-growing.

~

He had not noticed the time when he left the building. Oblivious to the descending moon, he finally became aware of the approaching dawn as golden twilight hues began to fill the air. He was entering that thin time during which the veil between worlds parts and one can walk in the in-between. That time when the years behind us blur, the present dissolves and our entire life exists in one moment—all the years behind us and ahead of us converge and breathe as one.

Of course it was near dawn, he thought to himself, remembering back to his youth when he used to go out just before sunrise to walk among the hills.

Of course it would happen now, his heart whispered unto the unseen, once more acknowledging the keen sense of synchronicity that the Fates possess.

Turning his downcast gaze upward, he took in the scene of the narrow streets ahead of him. The modern city faded as the memory of how the city once had been intensified. He was treading a surreal path; he did not know where he was going and yet at the same time he knew that, within this city, there was but one place he must end up.

The man moved swiftly down the narrow streets. He drew his shawl over his head. His stride was too fast for him to use his staff so he carried it—from time to time, the end dragging along the surface of the stone pathways.

As he passed by, the vendors were opening their shops, pilgrims were entering the streets and the call for Morning Prayer resounded throughout the Quarters—a haunting, Bedouin voice cried out, summoning all to submit unto God.

Crossing back and forth between the present and the past, as he walked the streets he returned with a sharp push to the past—to a violent moment when he was pulled down the pathways of the old city, driven unto the council that was to judge him. Herded along by the bullies on his heels, he could feel once more the jabs to his ribs dealt by those wielding wooden bats. Shoved to the ground, then kicked as he tried to rise, he could once more feel the burn of the skin peeling away from his palms as it did that night when, hands outstretched, he braced himself each time he was thrown down to the gritty floor of the earth. The core of his body felt sore as it had that night—the soft organs within bruised by the hard blows.

But then, suddenly, the man was pulled from the past back into the present by the obnoxious call of an eager merchant pointing to a painting depicting the scenes of the crucifixion—a tapestry woven of both myth and hard reality. Unable to comprehend the madness of it all, the man felt a grinding shock resound through his already reeling mind.

Plunged back into the past, he recalled being pushed forcefully through the heavy doors of the Temple, as they marched him before the council—that night they were to play the role of the puppets to those who sought to make a new church of their own. He faced the questions hurled at him over the inquisition. Time and deliberation compressed in this regression; no sooner than he was pushed through the doors did the lethal verdict come: "Blasphemer!"

In the space of a breath, he was pulled once more from the past, back into the present. Waking to find himself wading claustrophobically into a crowd of morning market-goers choking the narrow corridor.

Violently thrust back into the past, he found himself helpless and unarmed among a group of men. He felt the perverse amusement they derived from his fear. They were thrilled by the power they could exert over him—enthralled, like so many in their movement, to play the role of God.

Pulled from his past, he felt a stranger's hand grasp his arm; it was yet another merchant enthusiastically trying to sell him a faux crown of thorns. Lining the shelves of the merchant's shop were hollow plastic idols and figurines. His eyes continued down the length of the open shop; his jaw went lax in horror. There were a series of framed pictures in succession hanging along a makeshift wall composed of whitewashed pegboard. It was a portrait size image of a man—a man known to the world. It was the portrait of the ghost who had haunted his life. The man in the picture was exaggerated to the point where he lost his human quality. The colors chosen by the painter were primary and neon—utterly unnatural. The crown of thorns sat atop his head. Beads of blood gathered where the thorns cut into him. His complexion was pale, thin and sickly. His sapphire blue eyes were turned upward—nearly rolling back into his head looking to some divine presence not depicted. The nameless man gazed deeply into the picture in front of him. He saw his own reflection appear against the glass of the portrait. The two men blurred together for a moment, they were nothing alike yet were inseparable. His full face, contrasted the drawn out figure's. His dark, tanned skin reflected against the figure's pale complexion. His dark brown eyes stared into the figure's blue ones.

In that instant the man felt as though he had been struck swiftly in the back of the head by some invisible attacker. His perception was jolted, as though an earthquake had tilted the horizon. He was leveled by the madness of it—by the mockery, by the myth, by the belittled pain, by the lost truth and by the epic lie his simple life had been contorted into. He recoiled at the very thought of it—driven unto the edge of what his mind could comprehend as fate brought him to this perverse full-circle of events.

Breaking the grip the memories had upon him, he charged forward down the path, running through the gate and out into the hills, away from the inescapable events until, hoarse and out of breath, he came to the end of the path to see it looming before him—the place where the journey ended once and would again.

Pulled back into the past by a sharp pain cutting into him with such ferocity that the breath was pushed from his chest, the man found himself back with the armed mob, tied down—his pure body made a spattered mural of evil's hatred. Feeling that incomparable terror that comes when the fate of your body is in the hands of the immoral, blow after blow the memories of each lash coincided with each step bringing him along the path up the rocky mount.

The further we went the heavier the weight upon his heart grew. Lost in-between his past and present, one step was made upon the modern inlaid stone road while the next was made upon the dry dirt pathway of the past. He was pulled from his past by a holy man speaking words he could not understand he looked up to see a staff with a crucifix atop it raised before him, held by a priest who offered a blessing unto him. The man stared fixedly at the deathly figure set against the cross writhing in pain. It was a moment of agonizing horror frozen in time—hung on the walls of millions of followers. The aged cleric stared blankly at him, as he moved his withered hands—up and down, side to side—outlining the burden that the man had borne, which in turn had perversely become the symbol of the church that had been built. After making that shape that had outlined the years of the man's life, the priest walked on, reciting a prayer over and over again, as if in a trance.

Brought back into his past by a joint-severing pain, it felt as though the heaviness of the memory had dropped upon him. He fell to the ground. His knee dug into the dry gravel of the hillside; the force of the strike had embedded small stones into his open wounds.

On that day, as he traveled the path to the site, there had been those who followed him distraught and those who had followed him spouting damnation. In the past when he had collapsed under the weight of his burden there had been those who rushed to his aid, held back by the outstretched lance of the centurions and then there had been those who had rushed to kick him while he lay helpless, pelting insults after pitching rocks at his exposed back. The stones cast at him while he waked this path had embedded themselves in his life. The gravel of these streets had gathered in the intersections of the gashes splattered across his back and though the rocks had been physically removed in the days following the attack, fragments of these streets remained logged in the scar tissue still, preventing the full closure of the wounds.

Pulled from his past back into the present, he felt the sweat running down his brow—sweat not from the heat but from the exertion of the march. Pushing himself onward, his head spun and his heart swelled with pain, beating harshly against his ribs…the gripping memories playing out within him strangling him.

Blind to the pilgrims who thought him possessed, the man looked up to the path ahead of him—staring into his past where he saw once more the procession of the onlookers. The figures were dressed in robes, the women donning veils. All of them were shouting words he could not hear above his wailing heart. But then, sharply, the scene shifted once more and he saw a few early morning pilgrims walking ahead in suits and denim jeans. The path leading to the site had been worn down over the ages by those who sought to stand in that place where the life he had once lived had ended—the place he had been unable to escape since that day.

He could feel the weight of memory he was dragging up the hill. The voices of the ghosts grew loud in his mind, he could not hear their calls clearly back then—as he walked the path those many years ago but he could hear them clearly now. He could not feel the rocks they threw strike him those many years ago or the dirt they kick upon him as he passed by; however he could feel it now, and in the revelation of the hatred projected upon him the pain was forced deeper.

Falling as the gravel shifted beneath his feet, he struck the ground and inhaled a lung full of dust. His sweat-soaked face, now stained with dirt, was tattooed with a blooming bruise. He coughed violently—tears streaked the dirt on his cheek. And when at last his eyes cleared, he saw a sight he did not expect. Standing before him in the distance were the outlines of those quite familiar. Standing ahead of him he saw his mother, his father and his wife. He saw them all hysterical, helplessly watching the events play out, just as he was helplessly enduring it all.

For him it was a nightmare beyond comprehension but it was even more torturous to witness what he was going through reflected in their eyes. Beneath the ridge of his swollen brow and through the blood and dust he watched them breakdown—the whole family descending into madness…."

Traveling through the Holy Land, eighteen strangers are forced to take refuge in Jerusalem during a militant attack. Kept in close quarters in an abandoned building, over the course of four days this group of strangers begin a dialogue, discussing love and evil, religion and god; finding amongst their number a mysterious nameless man who poses a revolutionary perspective on these age-old questions.

Traveling through the Holy Land, eighteen strangers are forced to take refuge in Jerusalem during a militant attack. Kept in close quarters in an abandoned building, over the course of four days this group of strangers begin a dialogue, discussing love and evil, religion and god; finding amongst their number a mysterious nameless man who poses a revolutionary perspective on these age-old questions.

Visit the Homebound Publications Bookstore

March 19, 2012

Independent Publisher Homebound Publications Launches In Stonington | New Article

Recently I sat down with Bree Shirvell of the Stonington Patch to discuss my new role as Owner of Homebound Publications. We had a wonderful chat over coffee in a little cafe in downtown Mystic, Connecticut. A large part of identity is based on my youth spent along the coast of Connecticut; by that same hand, it is my intention for Homebound Publications to be deeply rooted in New England as well. I feel very grateful to have the support of my community.

♦

Independent Publisher Homebound Publications Launches In Stonington

Stonington resident L.M. Browning bought the publication company she helped found and relocated it to Pawcatuck.

Article By Bree Shirvell (Go to The Patch and read the article there >> Or continue below.)

Homebound Publications is a dream that began years ago in the mind of a then Stonington teenager. Last summer the dream became a reality in Boston, Massachusetts and it has now come home to Stonington.

The up-and-coming indie press officially launched in Stonington this past February. Under the direction of Founder and Lead Editor L.M. (Leslie) Browning, the independent publishing company hopes to produce four to eight titles in its first year and eight to ten in 2013.

Browning, a Stonington native and author, helped found the company for the Boston Publishing House Hiraeth Press in July of 2011. When she was given the opportunity to buy it several weeks ago she took it and relocated the business to Pawcatuck.

"Ever since I was 15 or 16 I've been writing Homebound Publications at the bottom of everything I wrote," Browning said.

Her own publishing company was always in the back of her mind but Browning said she was always afraid of the process. That is until she published her own book The Nameless Man last year with the then Hiraeth Press owned Homebound Publications.

"I got to know the process," Browning said.

Currently, Browning and her staff of one other full-timer and two part-timers are working out of her home office but they hope to take up office space in the area sometime this year.

The independent publishing house will focus on reflective and contemplative storytelling. Their current titles include The Nameless Man by Browning, The Sapphire Song by Todd Erick Pedersen, both nominated for the 2012 Pushcart Prize, and the soon to be released The Crucifixion by Theodore Richards. They will also be publishing a biannual journal titled The Wayfarer, which will feature travel writing, short stories, interviews, poetry and art.

"I love books, I love writing books, I love making books," Browning said. "And our little area is so supportive of the arts."

Browning said the books they publish will be in print and eBook form if the book is long enough.

"It's just a matter of time before it's all eBooks," Browning said a little sadly, adding that their eBooks sales don't come close to their print sales.

But the eBooks may fit into the company's environmental mission to be mindful of their carbon footprint. Until the day comes if it does when it's all eBooks the company's print books are published from paper certificated from the Forest Stewardship Council, Sustainable Forestry Initiative and Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification. The company will also be donating a percentage of their annual income to an environmental charity.

March 12, 2012

Morning Dockside | Journal Entry

[Journal Entry:] An early morning meeting cut short brings about a day without walls. Venturing down to the water's edge, settling dockside with a coffee and a new notebook, no creature was ever more content than I.

-Mystic, Connecticut | March 12, 2012

Look for L.M. Browning's forthcoming book: "Fleeting Moments of Fierce Clarity: The Travel Journal of a New England Poet" being published by Hiraeth Press December 2012 | Original Image by L.M. Browning © 2012

March 8, 2012

Poetic Broadsheet Collection | New in the Bookstore

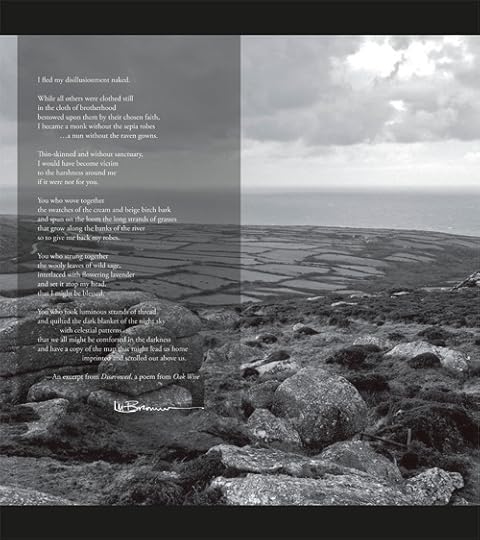

Poetic Broadsheet Collection

A collection of three broadsheets. One featuring excerpt from Oak Wise, one from Ruminations at Twilight and one from The Barren Plain

{11″ x 12″ | Printing on gloss stock | Signed by L.M. Browning}

Each broadsheet features an image from the Oak Wise collection by photographer Duncan George. Made in honor of Oak Wise's 2nd anniversary.

Buy the collection of 3 for $5.00

Special offer: in honor of Oak Wise's 2nd anniversary: While supplies last we are offering a free set of broadsheet with each purchase of L.M. Browning's contemplative poetry collection, available here in our bookstore for only $25.00. Go to the collection's page by clicking here >>

{Note: in preview each image as a copyright protection watermark that will not appear in the final edition}

Preview the Collection

Interview with Theodore Richards | A Look at His New Novel: The Crucifixion

The first lines of the The Crucifixion were written in a lonely corner of Mozambique, as Theodore Richards took shelter from a storm. There, huddled in a dark bathroom, in the poorest country on Earth, as the rain hammered down and leaked through the ceiling, Richards experienced a flash of clarity. One of those fleeting moments we all seek when the whole of our existence—past, present and future—becomes clear to us.

The story that came to him in this moment was one of Africa. The lines that came during that violent night were gathered up—brought home with him across the Atlantic and in time became a story that, not only told his journey but that of several generations of African Americans trying to find their place of belonging amid the harshest circumstances.

The Crucifixion is a modern American myth reframing the Old Testament in terms of the flight of African Americans from the Deep South during the Great Migration and the New Testament as the struggle for meaning in the modern, urban America. It is the story of a young man who is lost and alone, and must return to the city of his birth to find his place in the world. Ultimately, the man must awaken from the urban nightmare in which the world is "black and white" to realize that he and the city are embedded in a world of living color.

Recently, I sat down with Richards to discuss his latest work, which is due to be released in a few short weeks on Good Friday. This is not the first time I have had the pleasure of interviewing Theodore. A year ago I had the honor of interviewing him just before the release of his award-winning non-fiction book, Cosmosophia: Cosmology, Mysticism and the Birth of a New Myth. I have worked with him as a colleague in the year since; Cosmosophia has become a permanent fixture on my nightstand and my "go-to gift" for any friend beginning their spiritual search.

Over the time I have known him I have come to deeply admire Theodore's interfaith philosophy and more recently his proposal to bring an ecological awareness to children of the urban school system. He is a man who walks his talk. He is not a theorist, pondering in a study far removed from day-to-day reality; rather, he rolls up his sleeves and gets involved. He is a three-time author/poet, the executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a Dean and Lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary in New York City.

proposal to bring an ecological awareness to children of the urban school system. He is a man who walks his talk. He is not a theorist, pondering in a study far removed from day-to-day reality; rather, he rolls up his sleeves and gets involved. He is a three-time author/poet, the executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a Dean and Lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary in New York City.

[L.M.] Theodore, thank you for taking the time to sit down with me. Let's delve right in shall we. Your biggest news is, of course, the forthcoming release of your first novel. In a recent article published online, "The Crucifixion: Words from Mozambique" you described the origins of The Crucifixion. After reading the piece, I had the feeling that this book seems to have come to you very organically as if the story were the flash of a vision, rather than a conscious literary undertaking. Would you agree?

[Richards] I think that's accurate. I was pretty young when I started the work, and it really did arise organically out of some of the experiences I'd had at that point in my life. A lot of it had to do with my travels and how leaving the place I grew up allowed me to see that place, to see the place I came from, in new ways. The time I spent in Africa (I worked for an NGO in Zimbabwe) was a sort of coming of age experience for me, culminating in camping out on a beach in Mozambique. As I describe in the article, Mozambique was a difficult and beautiful place at the time. It was the poorest country on earth, having just endured something like 30 years of war. I began to write the book there when I had to find refuge from a storm in a little bathroom. Like any coming of age experience, it was a largely unconscious process. I was working through how to be a human being in a world that, well, like the world of The Crucifixion, was not yet entirely real, not entirely in living color. Of course, over the years I've returned to the manuscript and engaged in a more conscious process of crafting the story.

[L.M.] As a novelist myself, I realize that the fictional characters we create so often are imprinted with parts of our own personality. More than any of your previously published works, The Crucifixion seems a deeply personal significance. Were any of the main characters written from your own life? Underneath all the fiction, is one of these characters you?

[Richards] I think that question can only be answered by saying that—and maybe you'll agree with me here as a novelist—all the characters we create, if we are writing with honesty and integrity, are parts of us. And any story we tell comes out of some sort of experience. Obviously there are more similarities with my own identity and that of the main character, but I wouldn't go as far as saying any character is me—or anyone else for that matter. The book is a world that has come forth and, to some extent, has its own reality.

[L.M.] Essentially the main character of the book is struggling with the very human desire of wanting to find one's place of belonging. We all struggle with this longing. Over the years, as you defined yourself and your unique philosophy, do you feel you have found your place of belonging? In your opinion do we, as individuals, find our place of belonging or create it?

[Richards] I think that is an accurate description. (I am glad that came through!). I would say that we are all, always, wavering between longing and belonging, between the comfort of the womb and the terror and beauty of birth. To some extent I have found a sense of belonging—as an artist, as part of a spiritual community or movement, as a father, as a body in a the greater body of the earth. But belonging is a struggle, too. We don't exactly live in a culture that embraces creativity or depth, so the life of a poet or a philosopher can be a lonely one. I have an easier time finding community when I'm talking about basketball (which I love to do). But finding a sense of belonging is a process, never quite finished. I think that we both create and find community. Ecologically, we are certainly part of a community that is not completely of our own making. And we are born into families, born into traditions. But we also have the opportunity to create our own traditions, our own worlds.

[L.M.] Speaking of "creating our own traditions" and walking the "lonely path," share with us a bit about your spiritual journey. You have traveled to dozens of countries, studied at University of Chicago as well as The California Institute of Integral Studies, you are a dean and lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary, where you were ordained—these experiences certainly must have shaped your briefs. Where did your philosophical/contemplative life begin? Was there an inciting experience that sparked your interest in the deeper matters or was the curiosity always there?

[Richards] My spiritual journey has frequently also involved physical journeys. I mentioned traveling to Africa, but I also spent time in the Far East, India, the Middle East, Latin America. These all affected me profoundly. But I wouldn't want to leave out my experiences closer to home. I think that one of the major themes of The Crucifixion is that, while it can be important to leave in order to see one's home in a clearer way, the return is also important. For me, that home was urban America. It became clear to me early on that, while I had some early Christian influences on my life—my grandfather was a Baptist minister—I wanted to take an interfaith approach to spirituality. My daily spiritual practice, for example, has been mostly Taoist-based martial arts and meditation. The Crucifixion is the most Christian-themed book I think would ever write; and I employed those themes because they are American themes, not because they are necessarily any better than any others. I really believe that we are headed toward a revolution in how we approach spirituality, that the atomized notion of separate and distinct religions is going the way of many other Modern concepts. It is very Newtonian when you think about it. As I have grown in my spiritual life, I have also come to see that is not enough to merely say that "all religions are basically the same"—we are living at a moment in history when there are particular threads that we desperately need to find in our spiritual traditions, and each of these traditions expresses these threads a little bit differently: the mystical, that which embraces the paradox, the earth- and cosmos-centered. We need to remember that we are interconnected.

[L.M.] The Crucifixion deals with politically-charged subjects—tension between those of different races and religions—struggles that regrettably are still relevant today, especially on the heels of the attacks on the World Trade Center. In your own words The Crucifixion, "…reframes the Old Testament in terms of the flight of African Americans from the Deep South during the Great Migration and the New Testament as the struggle for meaning in the modern, urban America." Do you feel that bringing new context to such culturally embedded stories can help a generation better understand the greater significance of current events?

[Richards] I was once told by a Sufi that, because the Qur'an cannot be translated, Rumi's work was actually closer to the "Persian Qur'an" than any translation could be. The idea is that scripture isn't translatable outside of its context, that it must be breathed into life in the language in which it is read. So we have this book, The Bible, which is the lens through which so many Americans have understood themselves, their identities. But I wanted to ask these questions: how do those stories actually look in the American context? What is the journey that is unfolding in this country? Steinbeck or Baldwin or Whitman or Walker, for example, are writing books in this American Bible. I think most White Americans think that their story doesn't involve the African American experience. But there is no such thing as a "white" person without it's opposite, right? The very concept of whiteness was constructed to divide, was based on a dichotomy. We have crafted identity out of a series of dualisms: white and black, good and evil, etc. But the ultimate American gospel is that there is no America with reconciling those opposites. White America, in spite of the Right Wing rhetoric, can't even begin to answer the question of "who am I?" without Black America. Black America, on the other hand, understands America and the American experience more deeply than most White Americans can. As far as current events are concerned, I think that America's struggles are related to these unresolved dualisms. Whether it is the Islamic world or the natural world, we are seeking out our own identity by contrasting our selves to the other. But this never resolves anything; it only creates more hate, more destruction.

[L.M.] You would say then that: we cannot understand ourselves and our role on this earth until we understand that we are a part of one another?

[Richards] Yes. That's a good way to put it. Or we could say that we are all part of the same story, all humans, all a part of the Earth. We are of course, unique expressions of that same whole. I wouldn't want to give the impression that I am suggesting that the diversity of humanity is a bad thing. But diversity is something very different from isolation. The idea that the self is limited to the individual—what Alan Watts called "the skin-encapsulated ego—really is a big part of the problem. We are unique, but we are each like the story in the book about the bookshelves: we are collections of all the stories that have come into our lives.

[L.M.] An underlining message in The Crucifixion seem to be that, while the colors of the races composing this country vary and our religious perspectives differ, our individual and communal identity is defined by the whole. Not by just one side—the Blacks or the Whites, the Christians or the Muslims—but rather, by how all our paths intertwine. It is of course ignorance and fear that has always divided people; be it our own fear of what we do not understand or fear that has been driven into us by political rhetoric and/or religious fanaticisms. The first step in unifying peoples at odds with each other is to realize that, despite our differences in appearance or ideology, we all share the same story—the same cosmology, as it were. After reading a great deal of your work I must ask: Was it your intention in Handprints on the Womb, Cosmosophia and now The Crucifixion to help your readers see the unifying threads?

[Richards] I think maybe we want to think about how our stories can be at once unique and varied and, at the same time, draw us into a participation in a shared story. I think it is important for a culture to embrace its story, its traditions, because it helps to orient individuals to their own unique place in the world. The key, I think, is to allow that tradition not to become too concretized, too inflexible. The worldview of Christianity is quite different from that of, say, the Yoruba or the Buddhist practitioner. And that difference is OK—its beautiful, in fact. There are many ways that they all intersect and complement one another. Just look at Santeria, or the work of Thich Nhat Hanh or Thomas Merton or Meister Eckhart. As for unifying threads in all my work, there undoubtedly are some. I think it was more conscious in Handprints and Cosmosophia, because I put them together concurrently (although many of the poems are much older). The Crucifixion was less consciously crafted to have those unifying threads, but they are certainly there. All the work, of course, is a part of me and a part of my psyche. And just like the philosophy of Homebound states, I put a lot of emphasis on creating myths and telling stories, and that's what The Crucifixion is.

[L.M.] Looking ahead, the book comes out on Good Friday (April 6th, 2012.) Do you have any upcoming readings events or lectures planned?

[Richards] Yes. I have a launch party planned here in Chicago on the sixth of April. I will be at Malaprop's Bookstore in Asheville, NC, on April 27. I will be speaking in New York City on May 12, then at Breathe Books in Baltimore on the 15th. I also have an event at the Lakeshore Interfaith Institute in Michigan on July 1. The schedule is evolving and I should have a couple more in the next few months.

[L.M.] Finally, I am curious, in the introduction to Cosmosophia you reference the birth of your daughter; when your daughter is grown and sets down to reading this book, what would you hope she takes away from it?

[Richards] I pretty much wrote the book before Cosima was born, so I suppose it was inevitable I'd have a daughter one day. I'd like her to see that, while there is a great deal of suffering in the world and we often do terrible things to one another, a new world is possible if we can look that suffering in the face. I'd also like her to see that—again, even though I wrote it before she was born—our children are often our salvation. She has been mine.

Theodore Richards, PhD, is a poet, writer, and religious philosopher. He is a long time student of the Taoist martial art of Bagua and hatha yoga and has traveled, worked or studied in 25 different countries, including the South Pacific, the Far East, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. Theodore has received degrees from the University of Chicago, The California Institute of Integral Studies, Wisdom University, and the New Seminary where he was ordained. He has worked with inner city youth on the South Side of Chicago, Harlem, the South Bronx, and Oakland, where he was the director of YELLAWE, an innovative program for teens in Oakland created by Matthew Fox. He is the author of Handprints on the Womb, a collection of poetry; Cosmosophia: Cosmology, Mysticism, and the Birth of a New Myth, recipient of the Independent Publisher Awards Gold Medal in religion; and the forthcoming novel, The Crucifixion. Theodore Richards is the founder and executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a dean and lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary. He lives in Chicago with his wife and daughter.

L.M. Browning grew up in a small fishing village in Connecticut where she began writing at the age of 15. A longtime student of religion, nature and philosophy these themes permeate her work. Browning is a two-time Pushcart Prize nominated author. She has written a three-title contemplative poetry series: Oak Wise: Poetry Exploring an Ecological Faith, Ruminations at Twilight: Poetry Exploring the Sacred and The Barren Plain: Poetry Exploring the Reality of the Modern Wasteland. In late 2011 she celebrated the release of her first full-length novel: The Nameless Man, which was co-authored by Marianne Browning. Browning is a partner at Hiraeth Press—an Independent Publisher of Ecological titles. She is an Associate Editor of the bi-annual e-publication, Written River: A Journal of Eco-Poetics. Founder and Executive Editor of The Wayfarer: A Journal of Contemplative Literature and Founder and Lead-Editor of Homebound Publications. www.lmbrowning.com

Interview with Theodore Richards About His New Novel: The Crucifixion

The first lines of the The Crucifixion were written in a lonely corner of Mozambique, as Theodore Richards took shelter from a storm. There, huddled in a dark bathroom, in the poorest country on Earth, as the rain hammered down and leaked through the ceiling, Richards experienced a flash of clarity. One of those fleeting moments we all seek when the whole of our existence—past, present and future—becomes clear to us.

The story that came to him in this moment was one of Africa. The lines that came during that violent night were gathered up—brought home with him across the Atlantic and in time became a story that, not only told his journey but that of several generations of African Americans trying to find their place of belonging amid the harshest circumstances.

The Crucifixion is a modern American myth reframing the Old Testament in terms of the flight of African Americans from the Deep South during the Great Migration and the New Testament as the struggle for meaning in the modern, urban America. It is the story of a young man who is lost and alone, and must return to the city of his birth to find his place in the world. Ultimately, the man must awaken from the urban nightmare in which the world is "black and white" to realize that he and the city are embedded in a world of living color.

Recently, I sat down with Richards to discuss his latest work, which is due to be released in a few short weeks on Good Friday. This is not the first time I have had the pleasure of interviewing Theodore. A year ago I had the honor of interviewing him just before the release of his award-winning non-fiction book, Cosmosophia: Cosmology, Mysticism and the Birth of a New Myth. I have worked with him as a colleague in the year since; Cosmosophia has become a permanent fixture on my nightstand and my "go-to gift" for any friend beginning their spiritual search.

Over the time I have known him I have come to deeply admire Theodore's interfaith philosophy and more recently his proposal to bring an ecological awareness to children of the urban school system. He is a man who walks his talk. He is not a theorist, pondering in a study far removed from day-to-day reality; rather, he rolls up his sleeves and gets involved. He is a three-time author/poet, the executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a Dean and Lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary in New York City.

proposal to bring an ecological awareness to children of the urban school system. He is a man who walks his talk. He is not a theorist, pondering in a study far removed from day-to-day reality; rather, he rolls up his sleeves and gets involved. He is a three-time author/poet, the executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a Dean and Lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary in New York City.

[L.M.] Theodore, thank you for taking the time to sit down with me. Let's delve right in shall we. Your biggest news is, of course, the forthcoming release of your first novel. In a recent article published online, "The Crucifixion: Words from Mozambique" you described the origins of The Crucifixion. After reading the piece, I had the feeling that this book seems to have come to you very organically as if the story were the flash of a vision, rather than a conscious literary undertaking. Would you agree?

[Richards] I think that's accurate. I was pretty young when I started the work, and it really did arise organically out of some of the experiences I'd had at that point in my life. A lot of it had to do with my travels and how leaving the place I grew up allowed me to see that place, to see the place I came from, in new ways. The time I spent in Africa (I worked for an NGO in Zimbabwe) was a sort of coming of age experience for me, culminating in camping out on a beach in Mozambique. As I describe in the article, Mozambique was a difficult and beautiful place at the time. It was the poorest country on earth, having just endured something like 30 years of war. I began to write the book there when I had to find refuge from a storm in a little bathroom. Like any coming of age experience, it was a largely unconscious process. I was working through how to be a human being in a world that, well, like the world of The Crucifixion, was not yet entirely real, not entirely in living color. Of course, over the years I've returned to the manuscript and engaged in a more conscious process of crafting the story.

[L.M.] As a novelist myself, I realize that the fictional characters we create so often are imprinted with parts of our own personality. More than any of your previously published works, The Crucifixion seems a deeply personal significance. Were any of the main characters written from your own life? Underneath all the fiction, is one of these characters you?

[Richards] I think that question can only be answered by saying that—and maybe you'll agree with me here as a novelist—all the characters we create, if we are writing with honesty and integrity, are parts of us. And any story we tell comes out of some sort of experience. Obviously there are more similarities with my own identity and that of the main character, but I wouldn't go as far as saying any character is me—or anyone else for that matter. The book is a world that has come forth and, to some extent, has its own reality.

[L.M.] Essentially the main character of the book is struggling with the very human desire of wanting to find one's place of belonging. We all struggle with this longing. Over the years, as you defined yourself and your unique philosophy, do you feel you have found your place of belonging? In your opinion do we, as individuals, find our place of belonging or create it?

[Richards] I think that is an accurate description. (I am glad that came through!). I would say that we are all, always, wavering between longing and belonging, between the comfort of the womb and the terror and beauty of birth. To some extent I have found a sense of belonging—as an artist, as part of a spiritual community or movement, as a father, as a body in a the greater body of the earth. But belonging is a struggle, too. We don't exactly live in a culture that embraces creativity or depth, so the life of a poet or a philosopher can be a lonely one. I have an easier time finding community when I'm talking about basketball (which I love to do). But finding a sense of belonging is a process, never quite finished. I think that we both create and find community. Ecologically, we are certainly part of a community that is not completely of our own making. And we are born into families, born into traditions. But we also have the opportunity to create our own traditions, our own worlds.

[L.M.] Speaking of "creating our own traditions" and walking the "lonely path," share with us a bit about your spiritual journey. You have traveled to dozens of countries, studied at University of Chicago as well as The California Institute of Integral Studies, you are a dean and lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary, where you were ordained—these experiences certainly must have shaped your briefs. Where did your philosophical/contemplative life begin? Was there an inciting experience that sparked your interest in the deeper matters or was the curiosity always there?

[Richards] My spiritual journey has frequently also involved physical journeys. I mentioned traveling to Africa, but I also spent time in the Far East, India, the Middle East, Latin America. These all affected me profoundly. But I wouldn't want to leave out my experiences closer to home. I think that one of the major themes of The Crucifixion is that, while it can be important to leave in order to see one's home in a clearer way, the return is also important. For me, that home was urban America. It became clear to me early on that, while I had some early Christian influences on my life—my grandfather was a Baptist minister—I wanted to take an interfaith approach to spirituality. My daily spiritual practice, for example, has been mostly Taoist-based martial arts and meditation. The Crucifixion is the most Christian-themed book I think would ever write; and I employed those themes because they are American themes, not because they are necessarily any better than any others. I really believe that we are headed toward a revolution in how we approach spirituality, that the atomized notion of separate and distinct religions is going the way of many other Modern concepts. It is very Newtonian when you think about it. As I have grown in my spiritual life, I have also come to see that is not enough to merely say that "all religions are basically the same"—we are living at a moment in history when there are particular threads that we desperately need to find in our spiritual traditions, and each of these traditions expresses these threads a little bit differently: the mystical, that which embraces the paradox, the earth- and cosmos-centered. We need to remember that we are interconnected.

[L.M.] The Crucifixion deals with politically-charged subjects—tension between those of different races and religions—struggles that regrettably are still relevant today, especially on the heels of the attacks on the World Trade Center. In your own words The Crucifixion, "…reframes the Old Testament in terms of the flight of African Americans from the Deep South during the Great Migration and the New Testament as the struggle for meaning in the modern, urban America." Do you feel that bringing new context to such culturally embedded stories can help a generation better understand the greater significance of current events?

[Richards] I was once told by a Sufi that, because the Qur'an cannot be translated, Rumi's work was actually closer to the "Persian Qur'an" than any translation could be. The idea is that scripture isn't translatable outside of its context, that it must be breathed into life in the language in which it is read. So we have this book, The Bible, which is the lens through which so many Americans have understood themselves, their identities. But I wanted to ask these questions: how do those stories actually look in the American context? What is the journey that is unfolding in this country? Steinbeck or Baldwin or Whitman or Walker, for example, are writing books in this American Bible. I think most White Americans think that their story doesn't involve the African American experience. But there is no such thing as a "white" person without it's opposite, right? The very concept of whiteness was constructed to divide, was based on a dichotomy. We have crafted identity out of a series of dualisms: white and black, good and evil, etc. But the ultimate American gospel is that there is no America with reconciling those opposites. White America, in spite of the Right Wing rhetoric, can't even begin to answer the question of "who am I?" without Black America. Black America, on the other hand, understands America and the American experience more deeply than most White Americans can. As far as current events are concerned, I think that America's struggles are related to these unresolved dualisms. Whether it is the Islamic world or the natural world, we are seeking out our own identity by contrasting our selves to the other. But this never resolves anything; it only creates more hate, more destruction.

[L.M.] You would say then that: we cannot understand ourselves and our role on this earth until we understand that we are a part of one another?

[Richards] Yes. That's a good way to put it. Or we could say that we are all part of the same story, all humans, all a part of the Earth. We are of course, unique expressions of that same whole. I wouldn't want to give the impression that I am suggesting that the diversity of humanity is a bad thing. But diversity is something very different from isolation. The idea that the self is limited to the individual—what Alan Watts called "the skin-encapsulated ego—really is a big part of the problem. We are unique, but we are each like the story in the book about the bookshelves: we are collections of all the stories that have come into our lives.

[L.M.] An underlining message in The Crucifixion seem to be that, while the colors of the races composing this country vary and our religious perspectives differ, our individual and communal identity is defined by the whole. Not by just one side—the Blacks or the Whites, the Christians or the Muslims—but rather, by how all our paths intertwine. It is of course ignorance and fear that has always divided people; be it our own fear of what we do not understand or fear that has been driven into us by political rhetoric and/or religious fanaticisms. The first step in unifying peoples at odds with each other is to realize that, despite our differences in appearance or ideology, we all share the same story—the same cosmology, as it were. After reading a great deal of your work I must ask: Was it your intention in Handprints on the Womb, Cosmosophia and now The Crucifixion to help your readers see the unifying threads?

[Richards] I think maybe we want to think about how our stories can be at once unique and varied and, at the same time, draw us into a participation in a shared story. I think it is important for a culture to embrace its story, its traditions, because it helps to orient individuals to their own unique place in the world. The key, I think, is to allow that tradition not to become too concretized, too inflexible. The worldview of Christianity is quite different from that of, say, the Yoruba or the Buddhist practitioner. And that difference is OK—its beautiful, in fact. There are many ways that they all intersect and complement one another. Just look at Santeria, or the work of Thich Nhat Hanh or Thomas Merton or Meister Eckhart. As for unifying threads in all my work, there undoubtedly are some. I think it was more conscious in Handprints and Cosmosophia, because I put them together concurrently (although many of the poems are much older). The Crucifixion was less consciously crafted to have those unifying threads, but they are certainly there. All the work, of course, is a part of me and a part of my psyche. And just like the philosophy of Homebound states, I put a lot of emphasis on creating myths and telling stories, and that's what The Crucifixion is.

[L.M.] Looking ahead, the book comes out on Good Friday (April 6th, 2012.) Do you have any upcoming readings events or lectures planned?

[Richards] Yes. I have a launch party planned here in Chicago on the sixth of April. I will be at Malaprop's Bookstore in Asheville, NC, on April 27. I will be speaking in New York City on May 12, then at Breathe Books in Baltimore on the 15th. I also have an event at the Lakeshore Interfaith Institute in Michigan on July 1. The schedule is evolving and I should have a couple more in the next few months.

[L.M.] Finally, I am curious, in the introduction to Cosmosophia you reference the birth of your daughter; when your daughter is grown and sets down to reading this book, what would you hope she takes away from it?

[Richards] I pretty much wrote the book before Cosima was born, so I suppose it was inevitable I'd have a daughter one day. I'd like her to see that, while there is a great deal of suffering in the world and we often do terrible things to one another, a new world is possible if we can look that suffering in the face. I'd also like her to see that—again, even though I wrote it before she was born—our children are often our salvation. She has been mine.

Theodore Richards, PhD, is a poet, writer, and religious philosopher. He is a long time student of the Taoist martial art of Bagua and hatha yoga and has traveled, worked or studied in 25 different countries, including the South Pacific, the Far East, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. Theodore has received degrees from the University of Chicago, The California Institute of Integral Studies, Wisdom University, and the New Seminary where he was ordained. He has worked with inner city youth on the South Side of Chicago, Harlem, the South Bronx, and Oakland, where he was the director of YELLAWE, an innovative program for teens in Oakland created by Matthew Fox. He is the author of Handprints on the Womb, a collection of poetry; Cosmosophia: Cosmology, Mysticism, and the Birth of a New Myth, recipient of the Independent Publisher Awards Gold Medal in religion; and the forthcoming novel, The Crucifixion. Theodore Richards is the founder and executive director of The Chicago Wisdom Project and a dean and lecturer on world religions at The New Seminary. He lives in Chicago with his wife and daughter.

L.M. Browning grew up in a small fishing village in Connecticut where she began writing at the age of 15. A longtime student of religion, nature and philosophy these themes permeate her work. Browning is a two-time Pushcart Prize nominated author. She has written a three-title contemplative poetry series: Oak Wise: Poetry Exploring an Ecological Faith, Ruminations at Twilight: Poetry Exploring the Sacred and The Barren Plain: Poetry Exploring the Reality of the Modern Wasteland. In late 2011 she celebrated the release of her first full-length novel: The Nameless Man, which was co-authored by Marianne Browning. Browning is a partner at Hiraeth Press—an Independent Publisher of Ecological titles. She is an Associate Editor of the bi-annual e-publication, Written River: A Journal of Eco-Poetics. Founder and Executive Editor of The Wayfarer: A Journal of Contemplative Literature and Founder and Lead-Editor of Homebound Publications. www.lmbrowning.com

March 4, 2012

Dreams Are the Gestation of a Future Reality | A Journal Entry

[A recent reflection from my journal.] "Dreams are the gestation of a future reality. We do not come into being full-formed; we gather, build and grow. So too our matured identity—what we will be and do in this life—grows as well. Our reality begins as aspiration—vague dreams that sharpen over time until they are at last tangible. In nurturing our dreams we enable our future self to be born."

- L.M. Browning

March 3, 2012

Original Image: (c) L.M. Browning | Image: Sitting Fire-side in the Mountains.

February 22, 2012

A New Chapter | A Letter

It isn't often that we have the opportunity to fulfill a childhood dream. Years of work stretch out and days of tangible accomplishment come few and far between. But today, I find myself within one of those rare moments of fruition.

In my office, I have an archive of my early writings dating back to early 2000—long before I was published—when I wrote out of pure passion, with only a dim hope of ever being put into print. Some of these manuscripts have since gone on to be published, while others are still gathering, awaiting their time. At the bottom of each manuscript's title page is a scribbled note where the publisher attribution would normally be: "Homebound Publications."

In July 2011 I founded Homebound but the business itself was financially in the hands of another; however, recently I was presented with the opportunity to take Homebound as my own company. Trembling at the thought of such an undertaking during these hard financial times, I was determined nonetheless. After giving it a great deal of thought and speaking to a few trusted people in my life, I made the choice to leap and take over the business.

a few trusted people in my life, I made the choice to leap and take over the business.

I write this small note to you—our faithful readership—to mark a new chapter for our publishing house. In the coming weeks you will see many changes to Homebound. We have recently launched The Wayfarer: A Journal of Contemplative Literature. This is a biannual journal distributed by Homebound Publications. In it we will explore humanity's ongoing introspective journey. In early April we will celebrate the release of our first title of 2012: The Crucifixion by Theodore Richards. Finally, you may notice that our staff as expanded a bit over the transition. I welcome you to visit our "About" to read-up on the new faces that have recently come on-board.

At the end of what has been a very full day, one resounding conclusion echoes in my mind: At times we feel that our dreams may be far-off—impossible even, but all the while we can be working towards achieving them without fully realizing it. Follow your passion and you will find yourself face-to-face with dreams that you thought long passed.

With Gratitude

— L.M. Browning

Connecticut, Winter 2012

February 11, 2012

Marriage or Union – An Excerpt from The Nameless Man

(Featured in Chapter IX: The Other Side)

"When you speak of 'union' you are speaking of marriage?" Maria asked clarifying.

"Yes," the man said, giving his focus to this open-hearted woman, rather than debate with those who were adamantly deaf. "Although, I feel I should explain the difference between marriage and union.

"While one would propose that the definition of the word 'marriage' speaks of union and joining, it has been redefined over time and now concerns a legal union, not a genuine one. While some do indeed hold marriage to be the most sacred act a couple can make, in the end it has become meaningless—something easily entered into and easily left behind—a mockery of the nature of a true union. When you find the person you are meant to be with, the union between you and that person is already present; you do not create the union through ceremony, you simply awaken to it.

"Declaring those words 'I love you' or having another authority pronounce that you are joined to another does not create a union. We can easily deceive ourselves into believing we have found love and the pronouncements of others mean nothing.

"Fidelity, love, sharing—all these things that we swear to upon entering into a marriage are commitments that are already settled matters for those within a true union. A true union does not need vows to keep the two hearts in the relationship faithful to one another. A true union does not need to stipulate that they will be there for one another throughout all difficulty and unto death—such things are already granted.

"A marriage does not designate a union. A marriage is a legal partnership—a business partnership—not a bonding of hearts. A marriage can be performed by a minister of the law or of a certain faith, to any couple who applies, with no prerequisite that the two entering into the marriage know beyond a doubt that they are meant to be with each other or for that matter genuinely care for one another. Thus a marriage does not necessarily constitute a union; for a union is a joining that is carried out by Love itself, in a time before we were even born.

"Our union is made during our creation. When one soul is created within the Great Womb it is but one part of the whole; for one soul is actually composed of two Beings—each Being needing another half to complete them—one who we would call our union…our one love.

"Some call such a belief as this—two souls completing one another—a romantic notion; nonetheless, beneath the sentimentalized version of 'soulmates' lies the reality of two Beings sharing one soul.

"Some do not like the idea of their life's course being fated nor their love predestined—they reject such notions. Yet underneath such displays of fear and disbelief, even the critics want to believe they can have such a love as the one in which I speak.

"In entering into our life with the one we shall love already predestined, part of our freedom has not been taken from us," he explained. "Rather, our happiness and companionship in this life has been ensured.

"Over the centuries the sacred bond we have with our union has decayed into marriage, just as love has decayed into infatuation. As I said, a new reality with a belief in love removed, was formed and set in place. Marriage—a joining without the prerequisite of love—replaced union. When married, two people are joined in the eyes of the law yet whether there is a physical union of hearts already present may not be known and it is not required. The ceremony does not create the union between hearts; either the union was there before the ceremony or it never will be made."

Unable to keep quiet, Ari interjected, "You have a wife, do you not?" he asked bluntly, out of a desire to make a point.

The nameless man did not contradict.

"And you would have us believe that you did her the dishonor of never marrying her before the eyes of God?"

"Abiding by the laws of the land and the laws of the religion under which I was raised, I did 'marry' my wife but it was not the ceremony that bound us; we were already as one soul long before the ceremony, made so by the love that passed between us, not any vows taken. Had circumstances been different—had the ways of society not required the ceremony before the union was recognized—I would have seen no dishonor to my wife in forgoing the ceremony and neither would she; for I honored her in loving her and respecting her. Such sentiments are declared within a marriage—it is written into the script of the ceremony yet how often are these commitments met? A marriage will not hold us to good behavior, only our love for the one we are with will do so; thus the commonplace infidelity between couples seen throughout history.

"Within the old world when two people found their union there was indeed a wedding party to celebrate the love felt but there was no joining ceremony—no vows, no marriage license or other nonsense. There was simply the family—the community—celebrating the love between the two hearts. While in contrast, in this age, people feel free to move in and out of their marriages, knowing deep down that the ceremony means nothing if the love is not already present.

"Ari, you would declare that it dishonors a woman when a man wants to spend his life with her but does not marry her," the man said. Then posing the question, "Is it not a greater dishonor to enter into a marriage and declare the love to be lasting when deep down you are aware that it will not be?"

Waiting a moment for a response that did not come, the man continued, "Pretending that marriage equates union is the true dishonor.

"When we enter into a marriage, many of us delude ourselves into thinking that the one we are with is our one union. We deceive ourselves into thinking that we are 'in love,' maintaining our relationship through lies. And then on that inevitable day when the marriage ends, we tell ourselves that love is painful and temporary by nature; what's more, we begin to lose our belief that a real union of hearts even exists. When in actuality it was the illusion of a connection that we willfully took unto ourselves that was painful and temporary, not love. We wove the lie and then forgot we did so.

"When such things as this happen to us or happen between those around us—when we see marriages end or suffer the end of our own marriage—our belief in love is diminished, when in fact the bond between such peoples never should have been called 'love' at all. A madness of desperation, loneliness and lust has permeated humanity. Gripped by these feelings we are all eager to declare that we have found the one we are meant to be with, even when we know deep within ourselves that our union is not to be had with this person. By deluding ourselves into thinking we are loved or feel love for another, when in fact we do not, we belittle what love is and begin to believe that love is something that it is not.

"The rarity of our union—the fact that we have this bond with only one other within our entire existence, is what makes that one other person sacred to us. And yes, it can at the same time cause us distress when we do not believe that we will ever find the one other person we are meant to be with, among the billions of people now upon this Earth. But as I said in the beginning, our union was made before we were even born, it is not a matter of chance—the bond is destined, as is your meeting. Running along your parallel paths, your lives will converge. Until that day it is simply a matter of believing in love so you have the strength to wait for what is genuine.

"There was a poem written by those within my family, which I can recall from memory, that shows the emotions behind finding our union and what that means to our life."

The man's tone shifted, from a defensive one to that of prayer; as if he were recalling a psalm from his memory.

He began:

I breathe

but my heart shall not beat

until the arrival of you.

I shall dream

but only you can fulfill.

I shall call

but only you shall hear.

Only you shall know me

deeper than I know myself.

Only you can hear what I say,

that goes unsaid.

Only you hold all

that my heart needs.

Half of me was born within you—

we each were born to make the other whole.

I shall live,

but it is you

who will understand my life.

I shall act,

but only you can show me

the meaning in what I do.

I have a great depth inside me,

but only you can see it and cause it to rise.

My heart was made to gather what you give.

I live, but my heart beats within you.

I walk through this life,

but only you give me a bearing and a path.

I reach for the depths of love,

yet only you can help me touch them.

The life I was given is the love we have.

The world I live in is you.

My heart needs what only you can provide.

At night I try to rest,

but only you can give me

the peace I long for.

From across the distance I call you.

And through all obstacles

we come for one another.

I cannot die as long as you live.

My strength lies in you.

My reason, my hope and my belief—

all lie in you.

What we are together is who I am;

for we are united

and union is not a word

it is a state of being.

Click here to view the video on YouTube.