Michael Dobbs's Blog, page 3

September 21, 2012

Who 'lost' the Arab Spring

Having just completed a trilogy of books about decisive moments in the Cold War, I am bemused by the "Who lost the Arab Spring?" debate that suddenly seems to be gripping Washington. Like many foreign policy controversies, this one is driven more by the domestic political agenda -- and specifically the presidential election in November -- than informed analysis of actual events.

Having just completed a trilogy of books about decisive moments in the Cold War, I am bemused by the "Who lost the Arab Spring?" debate that suddenly seems to be gripping Washington. Like many foreign policy controversies, this one is driven more by the domestic political agenda -- and specifically the presidential election in November -- than informed analysis of actual events.To hear many Republicans talk, Barack Obama is to blame for the sudden upsurge of violence in the Arab world that claimed the life of our brave ambassador to Libya. The president's repeated "apologies" for American values have encouraged the extremists in Cairo, Benghazi, and elsewhere.

This kind of argument is similar to the "Who lost China?" debate that followed the Chinese Communist seizure of power in 1949. It supposes that China -- or the Arab Spring, in this case -- was ours to lose. The reality, of course, is that a U.S. president has very little influence over what happens in the paddy-fields of China or the streets of Cairo or the bazaars of Baghdad, unless he chooses to send in the First Armored Division. And as we have seen in Iraq, the forceful exercise of presidential power does not always produce the desired results.

A central theme of my three Cold War books -- Down with Big Brother, One Minute to Midnight, and Six Months in 1945 -- is the role of political leadership versus the chaotic forces of history. There are moments -- the Cuban missile crisis is a good example -- when the fate of the world hangs on the decisions and actions of a few individuals. More generally, however, the politicians are left scrambling to keep pace with events that are beyond their ability to control.

The most successful leaders are those who understand this fundamental truth, but keep plugging away all the same. At the height of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln lamented that he did not control events. "Events control me." And yet he somehow steered the country through the greatest crisis in its history. JFK expressed very similar sentiments during the Cuban missile crisis.

Of course, there are different types of foreign policy crises. As I describe in One Minute to Midnight , the missile crisis is a good example of a crisis that Kennedy and Khrushchev helped to create. This is a rare case where two men actually had the power to blow up the world. Through a series of mistakes and miscalculations, Kennedy and Khrushchev led the world to the brink of nuclear destruction -- but also had the wisdom to lead it back from the brink.

The onset of the Cold War was a different kind of crisis, more akin to the kind of crisis we are facing in the Middle East right now. In my forthcoming book, Six Months in 1945, I conclude that neither FDR, nor Stalin, nor Churchill, nor Truman wanted the Cold War. They sought to postpone it, for as long as they could. But it happened anyway -- because of the larger forces of history identified by Alexis de Tocqueville more than a century before.

"Their starting point is different and their courses are not the same," de Tocqueville wrote of Russia and America in 1839, "yet each of them seems marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe." I think we are seeing a historical upheaval of similar dimensions play out before our eyes on the streets of the Arab world.

Published on September 21, 2012 07:22

Who 'lost' the Arab Spring

Having just completed a trilogy of books about decisive moments in the Cold War, I am bemused by the "Who lost the Arab Spring?" debate that suddenly seems to be gripping Washington. Like many foreign policy controversies, this one is driven more by the domestic political agenda -- and specifically the presidential election in November -- than informed analysis of actual events.

Having just completed a trilogy of books about decisive moments in the Cold War, I am bemused by the "Who lost the Arab Spring?" debate that suddenly seems to be gripping Washington. Like many foreign policy controversies, this one is driven more by the domestic political agenda -- and specifically the presidential election in November -- than informed analysis of actual events.To hear many Republicans talk, Barack Obama is to blame for the sudden upsurge of violence in the Arab world that claimed the life of our brave ambassador to Libya. The president's repeated "apologies" for American values have encouraged the extremists in Cairo, Benghazi, and elsewhere.

This kind of argument is similar to the "Who lost China?" debate that followed the Chinese Communist seizure of power in 1949. It supposes that China -- or the Arab Spring, in this case -- was ours to lose. The reality, of course, is that a U.S. president has very little influence over what happens in the paddy-fields of China or the streets of Cairo or the bazaars of Baghdad, unless he chooses to send in the First Armored Division. And as we have seen in Iraq, the forceful exercise of presidential power does not always produce the desired results.

A central theme of my three Cold War books -- Down with Big Brother, One Minute to Midnight, and Six Months in 1945 -- is the role of political leadership versus the chaotic forces of history. There are moments -- the Cuban missile crisis is a good example -- when the fate of the world hangs on the decisions and actions of a few individuals. More generally, however, the politicians are left scrambling to keep pace with events that are beyond their ability to control.

The most successful leaders are those who understand this fundamental truth, but keep plugging away all the same. At the height of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln lamented that he did not control events. "Events control me." And yet he somehow steered the country through the greatest crisis in its history. JFK expressed very similar sentiments during the Cuban missile crisis.

Of course, there are different types of foreign policy crises. As I describe in One Minute to Midnight , the missile crisis is a good example of a crisis that Kennedy and Khrushchev helped to create. This is a rare case where two men actually had the power to blow up the world. Through a series of mistakes and miscalculations, Kennedy and Khrushchev led the world to the brink of nuclear destruction -- but also had the wisdom to lead it back from the brink.

The onset of the Cold War was a different kind of crisis, more akin to the kind of crisis we are facing in the Middle East right now. In my forthcoming book, Six Months in 1945, I conclude that neither FDR, nor Stalin, nor Churchill, nor Truman wanted the Cold War. They sought to postpone it, for as long as they could. But it happened anyway -- because of the larger forces of history identified by Alexis de Tocqueville more than a century before.

"Their starting point is different and their courses are not the same," de Tocqueville wrote of Russia and America in 1839, "yet each of them seems marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe." I think we are seeing a historical upheaval of similar dimensions play out before our eyes on the streets of the Arab world.

Published on September 21, 2012 06:22

September 7, 2012

'We fooled ourselves' - Bobby Kennedy

In my book One Minute to Midnight, I touch on a provocative question that relates to both the Cuban missile crisis and the run-up to the war in Iraq: Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear?

In my book One Minute to Midnight, I touch on a provocative question that relates to both the Cuban missile crisis and the run-up to the war in Iraq: Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear? In some ways, the Cuban case was the mirror opposite of the Iraq case. In Iraq, the Bush administration were intent on showing that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction—and lo and behold, the CIA produced the “evidence,” much of it fabricated, that helped prove the case. In Cuba, the intelligence agency helped the Kennedy administration fend off Republican charges that it was turning a blind eye to the installation of nuclear weapons on Cuba.

It was only on October 15—when it received incontrovertible photographic evidence of Soviet duplicity—that the agency finally reversed its estimate that the Soviet Union was not shipping nuclear missiles to Cuba. With congressional elections looming in November, President Kennedy succeeded in keeping a tight lid on any intelligence information that conflicted with the administration’s official position.

After my book appeared in 2008, I had the opportunity to ask the then-CIA director, General Michael Hayden, about the politicization of intelligence, in both the Cuba and Iraq cases. Not surprisingly, he defended the honor of his agency. He attributed mistaken analysis not to political pressure, but to a very human tendency to pay too much attention to conventional wisdom.

Explaining his point, he noted that the Soviets had never deployed nuclear missiles outside eastern Europe, prior to 1962. Analysts erroneously assumed that this status quo would continue to prevail. In the case of Iraq, analysts were swayed by the fact that Saddam Hussein did have a vigorous WMD program up until the first Gulf War in 1991. The analysts assumed that he was still developing WMD.

I think there is some truth in this explanation, but believe that politicization was also a factor. Political interference with the intelligence community operates in subtle ways. The overwhelming majority of analysts at the working level are non-political and highly professional, but they are also attuned to the demands of their bosses. Information and analysis is selected and filtered as it passes upwards through the ranks. The desire to supply the White House with information that will help the president build a political case can generate misinformation.

It is not only the American public that is fooled in such cases, it is also the commander-in-chief and his closest advisers. As Bobby Kennedy later remarked about the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles to Cuba, “we had been fooled by Khrushchev, but we had also fooled ourselves.”

Published on September 07, 2012 10:24

'We fooled ourselves' - Bobby Kennedy

In my book One Minute to Midnight, I touch on a provocative question that relates to both the Cuban missile crisis and the run-up to the war in Iraq: Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear?

In my book One Minute to Midnight, I touch on a provocative question that relates to both the Cuban missile crisis and the run-up to the war in Iraq: Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear? In some ways, the Cuban case was the mirror opposite of the Iraq case. In Iraq, the Bush administration were intent on showing that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction—and lo and behold, the CIA produced the “evidence,” much of it fabricated, that helped prove the case. In Cuba, the intelligence agency helped the Kennedy administration fend off Republican charges that it was turning a blind eye to the installation of nuclear weapons on Cuba.

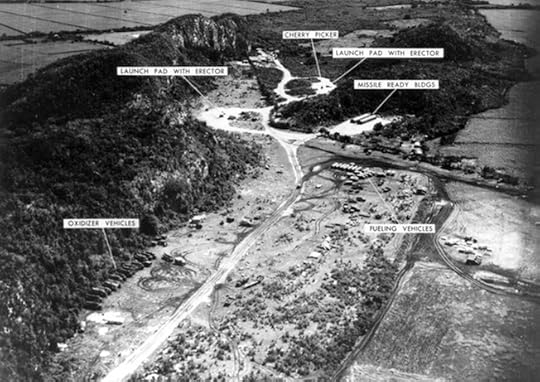

It was only on October 15—when it received incontrovertible photographic evidence of Soviet duplicity—that the agency finally reversed its estimate that the Soviet Union was not shipping nuclear missiles to Cuba. With congressional elections looming in November, President Kennedy succeeded in keeping a tight lid on any intelligence information that conflicted with the administration’s official position.

After my book appeared in 2008, I had the opportunity to ask the then-CIA director, General Michael Hayden, about the politicization of intelligence, in both the Cuba and Iraq cases. Not surprisingly, he defended the honor of his agency. He attributed mistaken analysis not to political pressure, but to a very human tendency to pay too much attention to conventional wisdom.

Explaining his point, he noted that the Soviets had never deployed nuclear missiles outside eastern Europe, prior to 1962. Analysts erroneously assumed that this status quo would continue to prevail. In the case of Iraq, analysts were swayed by the fact that Saddam Hussein did have a vigorous WMD program up until the first Gulf War in 1991. The analysts assumed that he was still developing WMD.

I think there is some truth in this explanation, but believe that politicization was also a factor. Political interference with the intelligence community operates in subtle ways. The overwhelming majority of analysts at the working level are non-political and highly professional, but they are also attuned to the demands of their bosses. Information and analysis is selected and filtered as it passes upwards through the ranks. The desire to supply the White House with information that will help the president build a political case can generate misinformation.

It is not only the American public that is fooled in such cases, it is also the commander-in-chief and his closest advisers. As Bobby Kennedy later remarked about the deployment of Soviet nuclear missiles to Cuba, “we had been fooled by Khrushchev, but we had also fooled ourselves.”

Published on September 07, 2012 09:24

August 30, 2012

Operation Checkered Shirt

Fifty years ago this month, an armada of Soviet ships crossed the Atlantic, headed toward Cuba. As this August 21 New York Times report shows, the Kennedy administration dismissed claims by Cuban exiles in Miami that the ships were carrying combat troops and sophisticated military equipment. U.S. officials were initially inclined to accept the Soviet explanation that most of the personnel arriving in Cuba were "civilian technicians," with a sprinkling of "military advisers."

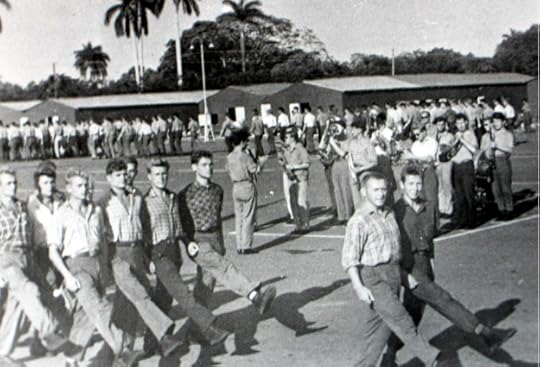

Fifty years ago this month, an armada of Soviet ships crossed the Atlantic, headed toward Cuba. As this August 21 New York Times report shows, the Kennedy administration dismissed claims by Cuban exiles in Miami that the ships were carrying combat troops and sophisticated military equipment. U.S. officials were initially inclined to accept the Soviet explanation that most of the personnel arriving in Cuba were "civilian technicians," with a sprinkling of "military advisers."As I describe in my book One Minute to Midnight, U.S. intelligence estimated Soviet troop strength in Cuba at between 4,000-4,500 as late as early October 1962, when by that time around 35,000 Soviet soldiers had arrived on the island. It was not until October 15 that the CIA figured out that these soldiers were equipped with nuclear weapons capable of destroying major American cities.

One reason for the bungled CIA intelligence was that the Russians are very good at what they called maskirovka , the art of concealment. They dressed their soldiers up to look like "agricultural technicians," in conformity with the cover story. The CIA did not latch on to the fact that the "agricultural technicians" were all wearing almost identical checkered shirts-see photograph above-leading Soviet wags to call the Cuban adventure "Operation Checkered Shirt."

But another reason for the miscalculation was the CIA's tendency to "mirror image." The intelligence analysts used American standards, rather than Russians standards, as the basis for measuring Soviet troop strength. They observed the number of Soviet ships crossing the Atlantic, figured out the likely deck space, and calculated the number of likely passengers. What they failed to understand was that the Russian soldiers were crammed below decks in almost slave transport conditions, with just sixteen square feet of living space per person, barely enough to lie down.

There was one person in the CIA who correctly guessed the reason for the massive Soviet armada crossing the Atlantic-and that was the director, John McCone. Informed that the Soviets were developing a sophisticated air defense system in Cuba, McCone reasoned that they must have something very important to hide-and guessed that it was nuclear missiles. But this was an inspired deduction, not an intelligence estimate, and it did not represent the official position of the CIA.

It should also be noted that McCone was the most senior Republican to serve in the Kennedy administration. His conclusions were politically embarrassing to the president, who was acutely aware of the approach of mid-term elections. In my next post, I will address a politically sensitive question that was raised again, four decades later, during the run-up to the Iraq War.

Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear?

Published on August 30, 2012 13:37

Operation Checkered Shirt

Fifty years ago this month, an armada of Soviet ships crossed the Atlantic, headed toward Cuba. As this August 21 New York Times report shows, the Kennedy administration dismissed claims by Cuban exiles in Miami that the ships were carrying combat troops and sophisticated military equipment. U.S. officials were initially inclined to accept the Soviet explanation that most of the personnel arriving in Cuba were "civilian technicians," with a sprinkling of "military advisers."

Fifty years ago this month, an armada of Soviet ships crossed the Atlantic, headed toward Cuba. As this August 21 New York Times report shows, the Kennedy administration dismissed claims by Cuban exiles in Miami that the ships were carrying combat troops and sophisticated military equipment. U.S. officials were initially inclined to accept the Soviet explanation that most of the personnel arriving in Cuba were "civilian technicians," with a sprinkling of "military advisers."As I describe in my book One Minute to Midnight, U.S. intelligence estimated Soviet troop strength in Cuba at between 4,000-4,500 as late as early October 1962, when by that time around 35,000 Soviet soldiers had arrived on the island. It was not until October 15 that the CIA figured out that these soldiers were equipped with nuclear weapons capable of destroying major American cities.

One reason for the bungled CIA intelligence was that the Russians are very good at what they called maskirovka , the art of concealment. They dressed their soldiers up to look like "agricultural technicians," in conformity with the cover story. The CIA did not latch on to the fact that the "agricultural technicians" were all wearing almost identical checkered shirts-see photograph above-leading Soviet wags to call the Cuban adventure "Operation Checkered Shirt."

But another reason for the miscalculation was the CIA's tendency to "mirror image." The intelligence analysts used American standards, rather than Russians standards, as the basis for measuring Soviet troop strength. They observed the number of Soviet ships crossing the Atlantic, figured out the likely deck space, and calculated the number of likely passengers. What they failed to understand was that the Russian soldiers were crammed below decks in almost slave transport conditions, with just sixteen square feet of living space per person, barely enough to lie down.

There was one person in the CIA who correctly guessed the reason for the massive Soviet armada crossing the Atlantic-and that was the director, John McCone. Informed that the Soviets were developing a sophisticated air defense system in Cuba, McCone reasoned that they must have something very important to hide-and guessed that it was nuclear missiles. But this was an inspired deduction, not an intelligence estimate, and it did not represent the official position of the CIA.

It should also be noted that McCone was the most senior Republican to serve in the Kennedy administration. His conclusions were politically embarrassing to the president, who was acutely aware of the approach of mid-term elections. In my next post, I will address a politically sensitive question that was raised again, four decades later, during the run-up to the Iraq War.

Did the intelligence people tell the president what they thought he wanted to hear?

Published on August 30, 2012 12:37

August 25, 2012

Author Q and A

I have posted a Q and A describing how I came to write my new book, Six Months in 1945. Key quote: "I am interested in hinge moments in history." You can read it here.

Published on August 25, 2012 13:22

August 21, 2012

Why I Write

I am not the kind of writer who derives pleasure from the physical act of writing. When I sit down in front of my computer screen (I rarely write in any other way) I waste a lot of time procrastinating. I stare out the window, surf the Internet, fetch myself another glass of orange juice, anything to postpone the dreaded task of actually writing.

So why do I write? The obvious answer is that it is the way I earn a living. The more elevated explanation is that writing helps me to think—and is the way I best communicate, not only with other people, but also with myself.

Writing is the way I organize and refine my ideas about a subject I have researched as a historian or witnessed as a journalist. It is not until I hammer out the words on the keyboard that I see everything in context and test the theories that have been spinning around in my head. It is at this moment that I pull the results of my research together and form them into a coherent narrative.

A good example is my forthcoming book, Six Months in 1945, on the period between the Yalta conference and the bombing of Hiroshima. The physical act of writing forced me to make sense of the bewildering rush of events that accompanied the fall of Nazi Germany and the fateful encounter of America and Russia, in the heart of Europe. It was then that I understood that the Cold War actually began during this six-month period, despite the best intentions of the principals (FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman.)

Above all, writing is a miraculous form of communication. One of my journalistic role models when I started out was the British reporter Nicholas Tomalin, who was killed by a Syrian rocket during the 1973 Yom Kippur war. Tomalin defined the reporter’s “required talent” as the “creation of interest,” explaining that a journalist “takes a dull, or specialist, or esoteric situation, and makes newspaper readers want to know about it.” Unlike university professors, journalists do not have a captive audience. We know we have to work hard to capture, and retain, an audience.

The trick, of course, is to do this without distorting the facts, and educate rather than titillate. It is tempting to try to create interest by hyping the story, filling your writing with superlatives such as “first,” “greatest,” “unprecedented,” ignoring the nuances that complicate the story. But it is much more satisfying to share the subtleties and complications with your readers. It is precisely the evidence that does not fit into the pre-cooked formulas that makes the research and writing process so interesting and rewarding.

In some ways, I find writing history books easier than daily journalism. This may be because I feel less constrained by the conventions of the trade, and am not looking over my shoulder so much. I like to tell stories with vivid characters, exotic locales, and an exciting, well-defined plot. They must also have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Academics can be condescending about narrative history, but I find that telling the story in chronological fashion is the best way to explain what actually happened—and to keep your readers turning the page which is, after all, the point of the entire exercise.

(Originally appeared in Publishers Weekly, August 17 2012.)

So why do I write? The obvious answer is that it is the way I earn a living. The more elevated explanation is that writing helps me to think—and is the way I best communicate, not only with other people, but also with myself.

Writing is the way I organize and refine my ideas about a subject I have researched as a historian or witnessed as a journalist. It is not until I hammer out the words on the keyboard that I see everything in context and test the theories that have been spinning around in my head. It is at this moment that I pull the results of my research together and form them into a coherent narrative.

A good example is my forthcoming book, Six Months in 1945, on the period between the Yalta conference and the bombing of Hiroshima. The physical act of writing forced me to make sense of the bewildering rush of events that accompanied the fall of Nazi Germany and the fateful encounter of America and Russia, in the heart of Europe. It was then that I understood that the Cold War actually began during this six-month period, despite the best intentions of the principals (FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman.)

Above all, writing is a miraculous form of communication. One of my journalistic role models when I started out was the British reporter Nicholas Tomalin, who was killed by a Syrian rocket during the 1973 Yom Kippur war. Tomalin defined the reporter’s “required talent” as the “creation of interest,” explaining that a journalist “takes a dull, or specialist, or esoteric situation, and makes newspaper readers want to know about it.” Unlike university professors, journalists do not have a captive audience. We know we have to work hard to capture, and retain, an audience.

The trick, of course, is to do this without distorting the facts, and educate rather than titillate. It is tempting to try to create interest by hyping the story, filling your writing with superlatives such as “first,” “greatest,” “unprecedented,” ignoring the nuances that complicate the story. But it is much more satisfying to share the subtleties and complications with your readers. It is precisely the evidence that does not fit into the pre-cooked formulas that makes the research and writing process so interesting and rewarding.

In some ways, I find writing history books easier than daily journalism. This may be because I feel less constrained by the conventions of the trade, and am not looking over my shoulder so much. I like to tell stories with vivid characters, exotic locales, and an exciting, well-defined plot. They must also have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Academics can be condescending about narrative history, but I find that telling the story in chronological fashion is the best way to explain what actually happened—and to keep your readers turning the page which is, after all, the point of the entire exercise.

(Originally appeared in Publishers Weekly, August 17 2012.)

Published on August 21, 2012 09:33

August 19, 2012

Cold War humor

I have tried to capture the light side of Doomsday in my three Cold War books as well as the dark side. Americans retained an ability to laugh at themselves even as they were building nuclear bomb shelters and teaching their children how to dive under their desks at school. The Cuban missile crisis, which was the subject of my book One Minute to Midnight, provided the plot for the most celebrated Cold War movie of all, Dr Strangelove.

Few people succeeded better at getting us to laugh at the macabre side of nuclear apocalypse than the singer-songwriter, Tom Lehrer, as exemplified by his song, "So long, Mom, I'm off to drop the bomb," which he described as a "song for World War III." Watch it here:

Few people succeeded better at getting us to laugh at the macabre side of nuclear apocalypse than the singer-songwriter, Tom Lehrer, as exemplified by his song, "So long, Mom, I'm off to drop the bomb," which he described as a "song for World War III." Watch it here:

Published on August 19, 2012 20:02

Tweeting the Cuban missile crisis

I am learning new things every day tweeting the Cuban missile crisis -- even though I spent more than two years researching the subject for my book, One Minute to Midnight. In my book, I focus on the famous "13 days" when the world came closer to nuclear destruction than ever before, but this project has helped me gain a better understanding of the buildup to the crisis and the frenzied nuclear arms race that seized the world in the summer of 1962.

I am learning new things every day tweeting the Cuban missile crisis -- even though I spent more than two years researching the subject for my book, One Minute to Midnight. In my book, I focus on the famous "13 days" when the world came closer to nuclear destruction than ever before, but this project has helped me gain a better understanding of the buildup to the crisis and the frenzied nuclear arms race that seized the world in the summer of 1962.The months leading up to the crisis were dominated by a superpower confrontation over Berlin and an orgy of nuclear testing in the atmosphere. The photograph above shows one of the nuclear tests carried out as part of the Operation Dominic series near Johnston Island in the Pacific. The Soviet Union was carrying out similar tests in the Arctic at Novaya Zemlya, with yields of up to 50 Megatons, the largest devices ever exploded.

It came as news to me at least that Nikita Khrushchev attempted to persuade John Kennedy to install a direct Moscow-Washington hotline in July 1962 -- but was rebuffed by his American counterpart, as we reported in a tweet on July 23. JFK said huffily that superpower communications were not the problem, and there was no need to improve them. This was at a time when it took ten to 12 hours to transmit a message from the White House to the Kremlin and vice versa, a communications delay that proved extremely dangerous during the missile crisis.

It was not until after the missile crisis that the Americans finally agreed to install a hotline with Moscow.

I was also intrigued to find out that the United States tested its first anti-ballistic weapon in July 1962, extending the arms race into space. The whole idea of "Star Wars" -- made famous by President Reagan -- goes back to the nuclear arms competition between Kennedy and Khrushchev.

The nuclear arms race sent millions of Americans diving under their desks in schools and triggered a wave of shelter-building. But it also spawned a new breed of zany, fatalistic humor, exemplified in this Tom Lehrer song, "So long, Mom, I'm off to drop the bomb, so don't wait up for me."

Published on August 19, 2012 09:35