C.B. Murphy's Blog, page 8

November 19, 2013

Free Copy of Cute Eats Cute!

Go to Goodreads.com and get a free copy of my book Cute Eats Cute!

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Cute Eats Cute

by C.B. Murphy

Giveaway ends December 19, 2013.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

November 15, 2013

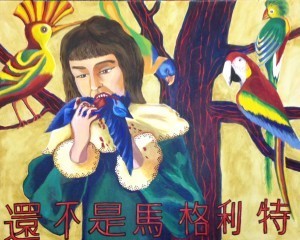

Homage to Magritte’s “Girl Eating a Bird”

I went to the amazing Magritte show currently at MOMA. I’ve been a fan of Magritte’s for a long time so it’s always a bit strange when someone you love gets a “fresh wave” of fame. Not that Magritte (or perhaps one should say the knock-offs of Magritte) has never been too far from the public’s eye. But I hadn’t seen many up close other than the amazing “The Menaced Assassin” which is in usually on display at MOMA and one of the few paintings I actually visit as one would visit a shrine of the Virgin, or in this case the murdered virgin.

But the painting that jumped out at me was “Girl Eating a Bird.” I have to admit the macabre aspect may have something to do with it, as I’ve been a fan of horror movies for a long time. But one has to factor in that this painting was done in 1927. It looks like someone lurking in the woods of “The Walking Dead.” Only the truly ahistorical would imagine we “post moderns” have any sort of special claim to horror. Surrealism was partly born out of the despair among intellectuals as the devastation of World War I—the war that convinced the world that it should outlaw chemical weapons. But there is still something very special about this young girl in a Victorian frock chomping on an uncooked songbird she obviously plucked from the tree behind her.

I’ve been looking for a new “series” for my painting and I began to consider an homage to Magritte. But what is an homage? Is it the same thing as the “painting hobby” (common in Europe) where people learn to paint replicas of famous paintings? I didn’t want to do that. For whatever reason when I started to paint my version of “Girl Eating a Bird” the colors shifted away from the drab grey-brown-black palette of much of Magritte’s work from this period. Then I came to the birds and this was when it got interesting.

I thought what if I painted brightly colored birds, tropical birds—an idea that might occur to another favorite painter of mine from this period, Henri Rousseau. I searched some Google Images for pictures of parrots and a image of Magritte’s “Girl” I could print out. Well, two things happened. One, I discovered that later in life Magritte painted a leaf with tiny bright tropical birds scattered across it approximately the scale of bugs. Then I discovered an image that Magritte himself painted of “Girl” that was in bright colors!

Backtracking a moment: a very brief touch on Magritte’s life. Many of Magritte’s most famous paintings were completed by the date the MOMA uses as their end bracket—1938. Magritte was 40. During the second World War, he was in Nazi-occupied Belgium and made a living counterfeiting currency and making replicas of famous paintings from masters like Picasso and Braque. Some biographies say “alleged” counterfeiting and some treat it as a fact, which is interesting in its own way. But after the war Magritte went through some kind of reaction against the “snobby” Parisians and the doctrinaire surrealism of his old buddies. He painted a number of gouache (opaque water color) works and called this his “Vache” period. Vache is French for cow and many took this to be a parody of the earlier “Fauvist” movement (meaning “wild animal.”)

The Fauves (of which the most famous was early Matisse differentiated themselves from everything else going on in this fertile artistic period (pre-World War I) by using “wild colors” (hence the wild animals). Today, post-Warhol, seeing bright pink and blue on a portrait is no big deal, but back then it shocked some people. Another game Magritte played (what else to call it?) was to paint in the style of Renoir, again a parody of a more traditional and beloved style than the in-your-face Surrealists.

Magritte’s colorful gouache of his “Girl Eating a Bird” was done during this Vache period, approximately 1946. Surprisingly, it was not an image readily accessible on the internet. There is an image library that has the rights to rent it out for commercial purposes but in their online catalog it is incorrectly confused with Magritte’s earlier “Girl” (an oil painting done in 1927).

But at this point I was already committed to my “homage” whatever that is. I decided that for my homage to “fit into” my “world style” (that is, inspired by multi-language posters) I would announce “This is not a Magritte” in one of my favorite graphic languages across the bottom. Thanks to Google Translate (and surprisingly given it’s a proper noun) I was able to find “not a Magritte” in what they call traditional Chinese.

不馬格利特

I still am considering writing a story (I have to admit influenced by “The Orphan Master’s Son”) of a young man in a rural Chinese village who gets a hold of a book of Magritte paintings and does his painting “Not a Magritte/ Girl Eating a Bird, in Bright Colors.”

November 13, 2013

Interview with Author Charles Murphy by Patti Frazee on Red Room

Interview with Author Charles Murphy

Check out author Patti Frazee‘s interview of me about my novel END OF MEN. If you’re an author (or reader) and unfamiliar with Red Room this is from their “About Us”:

Red Room made history by launching the only online bookstore that breaks down the “retail wall” between authors and readers. If you’re an author, Red Room shares its retail profits from your book sales with you, at least doubling your income, and connects you directly with all of your book buyers, something no other retailer in the world does. See how we do it. If you’re a reader, when you buy books on Red Room, your favorite authors appreciate it and want to meet you!

I have been featured recently with an interview about my book END OF MEN, conducted by Patti Frazee, the author of “Out of Harmony” and “Cirkus: A Novel.”

And get a load of this cover! Is that not in my territory?

November 5, 2013

A STORY WRITTEN FOR BOOMERS SPEAKS TO YOUNG ADULTS

When I began to write CUTE EATS CUTE, I intended to write about a contemporary family that was pulled down the slippery slope of controversy merely because they didn’t agree with each other. We like to think of society as civil and tolerant and often it is, but this family in some way anticipated the divisive age we are in now.

Though a parent of at least one avid reader who has recently moved on to “fully adult” literature, I never thought of myself as a writer for the young adult market. Most of the classes and writing groups I attended and learned from adhere to a rather snobby attitude that the only writing that matters is literary. This attitude put down anyone interested in what they grouped as genre work—lumping romance, science fiction, thrillers, mystery and horror into this supposedly second class ghetto.

In the beginning, all three characters in the story—the mother, father and their son Sam—spoke in their individual voices. But Sam’s voice was significantly stronger and more insistent that this was his story. Even then I didn’t realize this might be a young adult novel. I assumed the book merely required a “young voice” to get its message out about how the older generation’s righteousness hurt young people.

The other thing I wanted to do from the beginning was present a book about a controversial subject without having one character representing the “correct” position. Most of what passes for fiction especially in the ecological area is straightforward propaganda about who is “bad” and who is “good.”

By having each of Sam’s parents take a different position, I somewhat inadvertently stumbled on a key issue of the generations coming after the Boomers. The Boomers (God love us) are a passionate generation but also a self righteous and intolerant one. We are also a generation that is particularly good at pointing fingers and offended when people point them at us.

So the combination of the “young voice” of my narrator with the problematic situation of loving both his parents who disagreed on pretty much everything, replicated the condition many post-Boomer generations find themselves in. That is: they are told what to believe to qualify as “good” but not told how to handle it when someone you love disagrees with you.

Sam’s struggle is generational. Clearly he is a creature of his times, where “the media” largely determines who the heroes are and people follow them thinking they’ve taken an original position. But in attempting to discredit his father’s world (the hunters) Sam is faced with the conundrum that this tribe is neither stupid nor mean.

At the same time, his mother’s world, which aligns with his peers’ anti-hunting stance, strikes him as self indulgent, uninformed, and even comical. Distancing himself from both “set” positions is the core of the story. In other words, Sam has to find his own path even when his popularity is at stake.

I thought I was speaking wry wisdom to my own generation, cautioning us to be more careful about indoctrinating youth with our conclusions without showing them our process. But to a young reader I was revealing a world that reflects someone who got it, who sees the conundrum their parents and teachers put them in by demanding they accept our beliefs.

In some ways, it’s more of a classic story than a contemporary story. Isn’t that what every coming of age story is partly about? Someone says go to war but you don’t want to or someone says this kind of mistreatment of people is acceptable and you say it is not. Growing up is about challenging adults’ conclusions. It’s just that we Boomers thought we were different. We were the rebels; we found the best moral positions. Why would anyone have to work that out for themselves? Just get out there and man our barricades, we’ll tell you what to shout.

October 31, 2013

Painting in “45th Parallel” show at Phipps Center

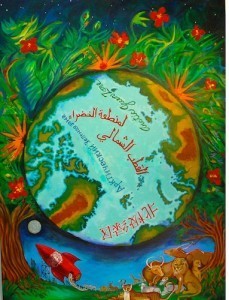

“The Arctic Green Zone” by C. B. Murphy

I just got this painting in a show at the Phipps Center for the Arts (Hudson, WI). The theme of the show is the “45th Parallel” celebrating the fact that the Twin Cities area is half way between the arctic and the equator. My image of of the earth shot from space after the global ice cap has melted. Perhaps it’s a poster from the future celebrating the lighter side of global warming. The words “Arctic Green Zone” appear in several graphically interesting languages (Chinese, Russian, and Arabic besides English). The foliage is an homage the the painter Rousseau who got famous for painting jungle scenes all from his visits to indoor plant conservatory in Paris. My animals are an homage to the “Peaceable Kingdom” painted by Edward Hicks in the early 1800s. The space ship with the UN logo is more or less Flash Gordon.

October 28, 2013

May Lou Reed Go to “This is the End” Heaven

I was in high school when my older brother brought home this strange album with a peel-able banana sticker on the cover called “The Velvet Underground.” I was fascinated by the dark lyrics and haunting voice of Nico, the German chanteuse. At the time, my buddies and I were set on becoming filmmakers. My friend made us cards with the image of a rooster and named our “company” Mona Films, Ltd. This was in a suburb of Detroit in 1968 on one side or another of the great inner city riot that had us all thinking the apocalypse had arrived. My friend and I went to NYC and found a small cinema where we could watch some Warhol films. After watching a guy lying in a bed for hours we thought, this guy’s no competition for us, he has no storyline. It was totally unlike our masterpiece “King Charlatan’s Game” which was a parody of Bergman juiced with with “sex and violence.” Shortly afterwards, my friend went on to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and really learned who Warhol was. I became influenced by the poets, writers and artists of the Black Mountain School, like Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, Stan Brakhage and Kenneth Anger. But Lou Reed remained an influence, especially in his Berlin phase when I started drawing my graphic novels with Zoographico Press. Lou, you worked hard and inspired many. I hope heaven is like the last scene in Franco’s “This is the End” movie when everyone gets to dance and sing. Here’s hoping.

October 15, 2013

Did the “Gravity” movie’s story originate here?

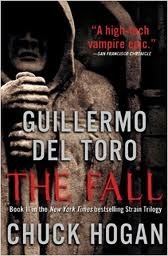

There is a minor character in The Fall, book two of Chuck Hogan/Guillermo Del Toro’s vampire trilogy, that bears a more than coincidental similarity to Sandra Bullock’s character in the hit movie Gravity. The character is Thalia Charles and she is alone in the international space station, worrying about losing contact with earth communications because of space debris. She is trained on Soyuz escape capsules, a key plot point of the movie. At one point she removes all her bulky gear and her hair floats around her head, reminiscent of an important image in the film some call the “fetus” scene, possibly an homage to 2001‘s Star-Child floating in space.

The other thing that is worth noting is that the director of Gravity, Alfonso Cuaron, is a friend and collaborator of Guillermo del Toro’s. the co-author (with Chuck Hogan). Cuaron and del Toro have worked together on a number of projects including Pan’s Labyrinth.

The plot of The Strain trilogy other than the few scenes with Thalia, has no connection to the plot of gravity at all. The trilogy is a dystopian “vampires take over the world” plot though with thoughtful variations you’d expect from del Toro. I really don’t know Chuck Hogan’s work, so I can’t speak to his influence.

What I’m picturing (completely speculative) is Cuaron reading del Toro’s trilogy, coming upon this amazing scene and thinking, this is a movie unto itself. Gravity. IMDB.com confirms this is not based on a book or screenplay. Cuaron and his son, Jonas, are the writers. The idea is a gift from del Toro.

October 11, 2013

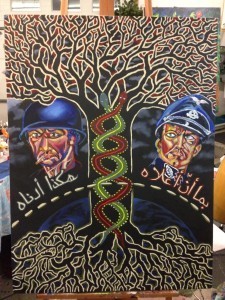

About Snakes and Burgers and Korea

The Rogue Anthropologist (thanks to Reddit) has recently viewed a burger commercial from Korea (see attached). In a way it can stand for itself, but would only say wow to Koreans see snakes in a different way than Americans. It brings up all kinds of questions (for an American).

In Korean mythology, Eobshin, the wealth goddess, appears as an eared, black snake. In Jeju Island, the goddess Chilseong and her seven daughters are all snakes. These goddesses are deities of orchards, courts, et cetera. According to the Jeju Pungtorok, “The people fear snakes. They worship it as a god…When they see a snake, they call it a great god, and do not kill it or chase it away.” The reason for snakes symbolizing worth was because they ate rats and other pests. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_m...)

In Korean culture, the word for snake, sa, is coincidentally a homonym for the number 4 and the word for death. In Korean locker rooms, in hotel corridors, and in buildings, you often find the number 4 missing (as the number 13 is often missing in the west), and one of the most feared creatures in Korean folklore, in the same category as the fox demon, is the snake woman. (http://www.endicott-studio.com/rdrm/f...)

There is also the fact that 2013 is the Year of the Snake in the Chinese calendar.

The “phenomenon” of the ad to the casual Western viewer is that on the one hand it is about things we are familiar with: burgers, franchises that sell them, hunger and eating, even envy of what is on another’s plate. The unfamiliar is overwhelming and a bit shocking. Why would a “hip” young man want to change himself into a reptile to each a large burger? Is this related to the current craze in Western culture for vampires, werewolves, and other shapeshifters? Could it be a parody of our interest in shapeshifting? More likely it isn’t referential to “The West” at all but resonates at a much deeper level to the Korean viewer, perhaps part parody, part outrageousness (i.e. attention-getting, what all advertising is ultimately about. Perhaps it is a simple thing, like some cultures are friendlier to various animals than others. There is the whole “eating dog” issue in the Orient (or eating horse meat in England) and why one group finds it natural and another an outrage.

September 26, 2013

Art for Art’s Sake and “Self Graffitiing”

In the end, every writer and artist has to face the misused and abused concept of “art for art’s sake.” In the end, are we creating to amuse ourselves (inform ourselves, if you want to be more positive) or are we “communicating” something whether it be questions, beauty, or our positions? Beauty is out of style in the fine art museums who now opt for communicating questions and/or commenting on the history of art to other insiders. This leaves a huge world of art “outside” the establishment, where the phrase “I like what I like” is relevant even if it sounds a bit defensive.

The issue of economics is invoked though not wholly relevant. Yes, people will shell out money (even big bucks) for art they “like” even if that art at the time it was made was an unappreciated exercise in “art for art’s sake”– an individual’s creative journey. A gross example would be Van Gogh. Yes, he wanted to make money (or rather his brother wanted to make money for him), but his main interest was getting it down, the vision thing, what he was pursuing. Many of the early experimenters in modern art (Picasso et al) struggled with the issue of “beauty” (portraits or landscapes recognized and appreciated immediately) versus the issue of pursuing of an artistic path.

Many movements such as Cubism and Futurism were attempts to use art as a kind of exploration of consciousness. Some of their products we still might see now as “beautiful” but their value is largely determined by the historical placement of the artist who painted them. Picasso’s least successful “experiments” are still valued highly because he in essence became a brand. The unknown artist who produced cubist works which may or may not be valuable (or only valuable as part of an historical movement) more than any inherent beauty in the works.

I recently showed some of my new paintings to a collector (a friend of the family) who owns a decent amount of valuable prints: Picassos, Lindners, Dubuffets, Dines. Nice stuff. I was taken aback by his critique of my work. “If you took out these parts…” He indicated a third of the content, the “disturbing” pop surrealist images. “You could sell these,” he said. That is, minus the disturbing content they might be just “beautiful” enough to decorate a hip restaurant. His defense of his position was: “Even Picasso did conventional work until he became famous.”

It is an interesting position though not wholly relevant to where I am with my painting. My current idea has been inspired by watching “Exit Through the Gift Shop” the controversial film by the graffiti artist Banksy about the artist who now goes by the name Mr. Brainwash. I’ve never been a huge fan of graffiti being old fashioned enough to balk at it’s “illegality” in defacing (or decorating) properties that don’t belong to you. That said, I can appreciate the movement (as long as they don’t decorate my building) for what it says about art and risk. The risk these artists are taking is primarily a physical risk, of being arrested or even of falling from great heights. Much of the actual imagery is not particularly challenging conceptually, falling generally into the category of Pop Surrealism or art that uses recognizable components (faces, objects, etc) albeit in unexpected or dreamlike ways.

My “take away” was that one could in effect graffiti one’s own work. I “found” some pieces in my oeuvre that no longer interested the “me” of the present day. Of course, had they been sold and gone I wouldn’t have had this option. But since I’m a hoarder, I had them. So my “inner graffiti artist” got a hold of them and hooked them up with another trope I had been working on for some time: inspiration from Ghanaian hand-painted movie posters. So I borrowed/appropriated images from the Ghanaian posters (that had already been borrowed/appropriated from Hollywood and other studio movies). Then, like a banksy in the night I “defaced” my own paintings in keeping with the “art for art’s sake” philosophy – I just wanted to see what they looked like. That was enough reason to do it.

April 5, 2013

Let me explain something about End of Men

On the Synchronicity of Titles and Implications Thereof

End of Men by C. B. Murphy (Zoographico Press, 2012)

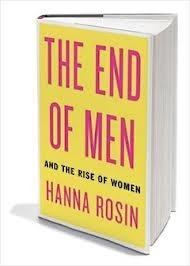

The End of Men and the Rise of Women by Hanna Rosin (Riverhead Books, 2012)

An interview with author C. B. Murphy

GT: We’re here to discuss the synchronicity of the publication of your novel entitled END OF MEN (EOM) followed closely by the publication of Hanna Rosin’s THE END OF MEN: AND THE RISE OF WOMEN (TEOM). Would you care to start off by commenting on this?

CB: In July 2010, the Atlantic Monthly ran an article of Ms Rosin’s using the working title of my forthcoming book. Even though I had been writing my novel for quite a few years using the EOM title, I considered changing it at that time. I struggled to come up with another title I liked as much and in the end reverted to EOM, in large part due to the fact that the title is used in my plot. The premise is not new and has been kicking around a long time in journalism (see Harper’s forum in 1999 “Who Needs Men?”) and Susan Faludi’s “Stiffed” in 2000. Interestingly, in the September 30, 2012 issue The New York Times featured an article entitled “The Myth of Male Decline” that attempting to debunk many of Ms. Rosin’s sweeping conclusions.

I hate to admit how long I’ve been working on this book with this title, but it seemed like a more outrageous title (and concept) when I initially conceived the original concept and plot. Since then, it has become a far more common phrase and concept, even “cliché” as a friend dared to suggest.

GT: Obviously, since your EOM is a novel and Ms Rosin’s TEOM is a nonfiction investigation of the current state of the genders relative to each other and the economy, what do you have to say to the person who “accidentally” buys your book instead of hers?

CB: (laughs) Well, ideally they’ll be pleased they’ve “accidentally” discovered something to read that isn’t overly topical, highly debatable and fairly dated! No, seriously, I read Ms Rosin’s Atlantic piece and I agree with many of her points about the “decline of men” in our society. I think a well-informed reader enjoys both fiction and non-fiction but read them for different reasons. Fiction, though it can be topical and timely, often addresses the human condition but not the immediate events in the news—even when it uses those events to frame a story, such as “9/11” or World War II.

GT: How does your title EOM relate to that same theme expressed in her book?

CB: The three main characters in EOM offer distinct points-of-view that consider Ms. Rosin’s exploration of gender: Ben, a financier in Chicago, his wife Kay who works at an outsider art gallery and Gordon, an old college friend who runs a film school on an Italian island. There are a number of ways in which my title reverberates in the characters’ lives though within the story there is an actual gallery exhibit Kay is curating, a show of feminist art called “The End of Men.” To bring notoriety to the show, Kay invites Gordon and his more famous collaborator Shiraz (an Iranian filmmaker) to show their film at her relatively small Chicago gallery. Controversy arises from several quarters. Ben is shocked and challenged to find his “buddies” from his old wild life (he had an affair with Shiraz in college) showing up in his new staid life, more or less stripped of his early interest in “avante-garde” film and alternate lifestyles.

Kay is representative of several of the women in Ms Rosin’s TEOM. They are directed, upscale and ambitious. Though feminism brings it own challenges (the urban feminists disparagingly call Kay a “beige”), Kay sees the world as a place where she can make a difference through intelligence and education. Ben struggles with many of the challenges and issues facing contemporary men. He’s worked for his father, an old-fashioned cold tyrant, in a field where he’s made money at the expense of nurturing his soul. His father’s death triggers a kind of spiritual crisis for him, not unlike the “crisis of Western civilization” where the advantages of patriarchy are being challenged by the politics of fairness and economic stratification.

GT: Talk about the different kinds of feminism in your two major characters, Kay and Shiraz.

CB: Shiraz is an unusual character. She is partly based on the Iranian photographer, Shirin Neshat, who takes a complex view of women in Islam. Neshat is considered both a feminist and supportive of traditional Islam. My character, Shiraz, gives out similar “mixed messages” about feminism. Like Ms. Neshat, Shiraz was raised by westernized Iranian parents and sent to American schools in the 1970s. Neshat went to Californian schools, Shiraz to the University of Michigan. Shiraz has been working with Gordon on a complex oeuvre not unlike the work of Matthew Barney—mythopoetic, surreal, controversial. Over the years their partnership has become strained as Gordon’s use of drugs and propensity toward promiscuity has veered him away from her concerns—a thoughtful re-imagining of the coming age where women will dominate the world (not unlike a spiritual interpretation of Rosin’s TEOM).

Like Neshat, Shiraz shows ambivalence about radical Islam and hopes there could be a role for a “liberated” woman like herself who embraces both radical self expression and the movement for a world Caliphate (which she interprets ironically as a return to matriarchy).

Unlike Rosin’s worldview, Shiraz sees the ages in terms of mystical movements or zeitgeists that overshadow any short-term socio-economic “phases” that can easily move one way or another.

GT: How would your characters react to Ms Rosin’s book?

CB: Great question! Kay would like it and see it as more welcome evidence that the world is shifting, most likely in her favor. However, she has mixed feelings about the way the culture (and feminism) has been evolving. On the one hand, she promotes feminist art but she has to put up with prejudices her female co-workers hold against not only “people with money” (what they’re calling the 1% nowadays) but the implication that a married suburban woman cannot legitimately be feminist especially if her husband “supports her” by working in a traditionally male field like finance.

At the same time, Kay feels she missed out on “the Sixties” that she knows her older husband, Ben, experienced, especially at the University of Michigan (when he ran around with Gordon and Shiraz). She is concerned that the cultural shifts (especially for women) since the Sixties have not been all positive. She romanticizes a more free, fun, and creative time (perhaps when men and women “naturally” got along better) and is not sure the cranky women who surround her have internalized the best lessons of that time. So in some ways, she would be critical of Rosin’s premise that “women wear the pants” now and that is a good thing. She would probably say something like, “Why don’t we all wear skirts, or kilts?”

G: What about the male characters, how would they react to Rosin’s THE END OF MEN?

CB: Ben, at least as his character portrayed in the beginning of the book, would say, “They can have it!” (meaning the world). He feels that the patriarchy hasn’t delivered its elusive promises of happiness to him or those around him. His mother is a strong woman in an old-fashioned, “Bette Davis” way, so the idea that women are repressed is a bit hard for him to understand emotionally, if not intellectually. Like Kay (though in a completely different way), he questions both the cultures and his own direction since the Sixties. Unlike Kay, however, he has experienced the dark side of that time—narcissism, drug abuse, nihilism, and economic stagnation—so doesn’t think of it as a place he’d want to go back to.

For Gordon, the Sixties never ended nor would he want them to. His world remains as it was at that time, a creative place that lives in opposition to (but ironically dependent on) the “mainstream culture” or whatever he would call it. Like many artists who take a classic revolutionary (anti-bourgeoisie) position in their work, Gordon depends on grants from museums and counts of the well-heeled to send their budding artistes to his exotic art school. At the same time, Gordon sees himself as an occultist (indeed, he is a follower of Aleister Crowley) who in the tradition of the Golden Dawn see themselves as responding to “hidden” forces, issues and messages that are not accessible to anyone merely because they see themselves as counter-cultural. There is a certain elitism to occult thought that has been downplayed by the New Age’s embrace of its “healing power.”

GT: What would you say to the person who wanted to read Rosin’s TEOM and ended up buying your EOM instead?

CB: (laughs). That’s hard to say. I’d like to think our shared audience see themselves as people who like to stay informed, critique trend analysis and develop their own ideas about what’s going on in the world today. As such, I could see how someone expecting to receive an academic cultural analysis would be surprised to be holding a work of fiction in his or her hands instead. But, as we know, people by nature want to be entertained, and a great story that mirrors reality (and does it well) is a compliment to any nonfiction counterpart.

Of course, regardless of purchase order, my hope is that readers turn around and buy both books!