Starr Z. Davies's Blog, page 3

September 3, 2020

Review: Conqueror by Conn Iggulden

I have been fascinated with the reign of Kublai Khan for years, and I couldn’t wait to read this book to see his empire come to life! If you don’t already know, I started reading the Khan Dynasty series months ago, and the final book, Conqueror, was the one I was most excited to read...

The post Review: Conqueror by Conn Iggulden appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

August 13, 2020

Mongolian Military Structure

Mongolians were famously known for their brutal battle tactics and their ability to move faster than any other army in Asia or Europe. This allowed them to conquer and build one of the largest continuous empires ever. It even surpassed that of Alexander the Great and the Roman Empire when it reached its peak. The...

The post Mongolian Military Structure appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

August 3, 2020

Kindle Fire and 20 YA Fantasy Books #Giveaway with 5 Chances to Win

Hello and Happy Monday! Have I ever got a treat for you! I recently connected with fellow author Abby Arthur (TWINS OF SHADOW), and I’m excited to share that she’s running a HUGE giveaway this month. She’s giving away a total of 20 YA Fantasy novels and a new eReader from Amazon – the Kindle Fire...

The post Kindle Fire and 20 YA Fantasy Books #Giveaway with 5 Chances to Win appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

July 25, 2020

Review: Empire of Silver by Conn Iggulden

My deep dive into Mongolian history continues with a read-through of the fourth book in the Khan Series, Empire of Silver, by Conn Iggulden. Genghis Khan is dead. His empire is left to his son Ogedai, but can Ogedai gain enough support to become khan before his brother Chagatai steals it away from him? This...

The post Review: Empire of Silver by Conn Iggulden appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

June 21, 2020

Review: Bones of the Hills by Conn Iggulden

I finally finished Bones of the Hills, book 3 in the Khan/Conquerer series. The book took a while to read, but that was mostly just because life turned a bit chaotic for a while.

The first book in the series, Wolf of the Plains, explored the early life of Genghis Khan and how he brought the clans of Mongolia together. You can refresh your memory with my full review here.

The second book in the series, Lords of the Bow, explored Genghis Khan’s conquests against the Chin and his defeat of the emperor. I also cover that book in this review.

Bones of the Hills is the third book in the series, and in this book, Genghis takes his entire Mongol nation into Arab lands to destroy the shah and decimate those who oppose his strength. But it is also at this point when his age begins wearing on him and his men begin doubting his ambitions.

Bones of the Hills is the third book in the series, and in this book, Genghis takes his entire Mongol nation into Arab lands to destroy the shah and decimate those who oppose his strength. But it is also at this point when his age begins wearing on him and his men begin doubting his ambitions.

It should be noted that of all the generals who followed Genghis Khan, only his oldest son — whom many doubted was actually his son — openly opposed him. This book covers the bitter relationship between Jochi and Chagatai, Genghis’ two oldest sons, as well as his own relationship with Jochi. The anger and pain Jochi feels toward his father are brought on by Genghis’ own treatment of this eldest son. I found the story of Jochi to be the most compelling part of this book. His heart, his strength, and his desperate need for his father to show him any form of love or pride. It was a heartbreaking tale.

The book had a lot to unpack: Tsubodai’s dedication to his khan against his love for Jochi; Jochi’s desire to be accepted by his father; Genghis’ stubborn determination to kill any who oppose him; Chagatai’s arrogance, short temper, and hate for his brother Jochi.

While this book covered a lot of ground as the Mongols conquered the Arabs, the focus felt more centered around the personal struggles of the men beneath Genghis in his final years. The characters had much more depth and emotion than any of the other books in the series thus far. The action certainly showed the epic, brutal strength of the Mongol army as they destroyed forces three times their size.

With all those strengths, this book still had weaknesses.

First was the shifting character perspective within a single section. This style of writing is clearly a preference for Iggulden, but I feel like it forces too much distance between the reader and the characters when we hop from one head to the next. I have mentioned this in the other reviews as well. Though I did feel more connected to the characters in this book, I still feel it could have benefited from a tighter point of view to really punch those emotions home.

The second weakness was my overwhelming disappointment with the complete lack of role Ogedai has in the book. If you know anything about Genghis Khan’s empire, you know that Ogedai is actually the son who will become khan when his father dies. Yet Ogedai only gets a few passing mentions in this book. Jochi and Chagatai’s hatred for each other takes center stage, leaving no space whatsoever for Ogedai to grow in our hearts before he takes over. For me, as a reader, this was the biggest failing of this book — and so far this series.

Would I recommend this book? Absolutely. Just be aware of the shortcomings before you dive in.

The post Review: Bones of the Hills by Conn Iggulden appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

June 13, 2020

Why I Chose to Write Historical Fiction

Historical fiction. It’s a genre of books that can be scary to some. I will admit that in my younger years I considered historical fiction a boring, drab retelling of history. But I just hadn’t read the right story. And once I did, it opened my eyes to a world of fantastic novels.

My understanding of what historical fiction is has changed significantly. I have read quite a few different series — mostly ancient historical fiction: Romance of the Three Kingdoms, The Conqueror series about Genghis Khan, the Atilla series, and quite a few about the Roman Empire or Julius Caesar.

Historical fiction isn’t something to shy away from. The best books in the genre that I’ve read have recreated dynamic characters, battles, or settings in creative or epic ways. Sometimes all of these combined.

Why I chose to write historical fiction:

For those of you who follow me closely, I know you are probably wondering why I have selected historical fiction after publishing two young adult dystopian novels. Genre-switching can often be a turn-off to readers. I understand that, but my hope is that, after reading the Ordinary series, you will see how deeply I dive into characters. I hope you enjoy my writing enough to try something new and step outside your comfort zone — as I am doing.

I chose to write this particular historical fiction because of one woman. Mandukhai the Wise.

As I mentioned, I like writing strong, character-driven stories. I love reading them as well. In fact, I will choose a book with a strong character over a book with a compelling story every time (and if the book has both, it’s a huge win for me). No one in history has inspired me as much as the true story of Mongol Queen Mandukhai the Wise. She lived in a society where men dominated warfare and politics; where a woman’s role was primarily in childbirth and raising children, as well as maintaining the home. Queens, in particular, faced a lot of pressure to produce multiple male heirs.

As I mentioned, I like writing strong, character-driven stories. I love reading them as well. In fact, I will choose a book with a strong character over a book with a compelling story every time (and if the book has both, it’s a huge win for me). No one in history has inspired me as much as the true story of Mongol Queen Mandukhai the Wise. She lived in a society where men dominated warfare and politics; where a woman’s role was primarily in childbirth and raising children, as well as maintaining the home. Queens, in particular, faced a lot of pressure to produce multiple male heirs.

But Mandukhai was different. She had the heart of a warrior and the soul of a true leader. She stood up to the men. She fought for what she believed in. When the line of royal heirs seemed extinct and clans began fighting each other for power, she stood up against them all and reigned them in. She restored order to a fractured empire. She pushed the Ming empire to continue building the Great Wall to keep her hordes out. A woman like this deserves to have her story told.

I hope you agree and will find her story worth reading. I will certainly do my best to do justice to her life.

What you can expect from the Fractured Empire series:

I have done a lot of research about this woman and her life, as well as the life of her husband. I have contacted specialists in the field and corresponded with notable experts such as Jack Weatherford. What I want, more than anything, is to tell her story in a way that is as accurate as possible, compelling to readers of all types, and strongly rooted in her own world, feelings, and motivations. But to share a great retelling, I have to take creative liberties.

So here is what you can expect from the series.

Intrigue. And lots of it. Honestly, intrigue will be a bigger part of the story than actual warfare, so for people who enjoy such things, this will be a great fit. In the early years of her reign, the Mongol empire was rife with intrigue, sexual politics, and war. All of these things will create — I hope — an epic tale about a strong, dynastic woman.

Loose historical accuracy. I’m trying to keep her story as true to real life as possible, but keeping track of the comings and goings of Mongolian clans and battles can be overwhelming (more here). My goal is to focus only on the key points that are important to her story and build on them. That means that some factual history could be lost through the cracks in favor of a great book. I hope that doesn’t offend any delicate historical sensibilities.

Actual historical figures. I have an extensive list of people who fought in the empire during her time, and I will be using that list to the best of my ability. However, my representation of those people may not always be historically accurate. Many of them don’t have much written so I will be taking creative liberties. Just as important as their place in history is, for this series, using them to create strong characters with their own clear motivations that will drive the plot forward.

Sex, abuse, and violence. I’ll just get this out of the way now. This is why I cannot produce the series as a young adult series. Mongols were very sexual, and they could be brutal. If I don’t represent this aspect of their daily life, I will not be doing the story justice.

~~~

I am excited about this project. Her story has been in the back of my mind since I first learned about her in 2012. I knew as soon as I read Jack Weatherford’s book, The Secret History of the Mongol Queens, that one day I would have to share her story with the world.

The time has come. I’ve researched. I’ve plotted and planned. And now it’s time to dive right in.

The Fractured Empire series will likely be my only historical fiction series. While I can’t say what the future holds, I can say that no other story has struck me like Mandukhai’s. I hope you will take the journey with me.

The post Why I Chose to Write Historical Fiction appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

June 12, 2020

Mongolian Clans Affiliations of the Late 15th Century – Part II

Yesterday, I shared some of my frustration with you regarding the organization of the Mongolian clans. I even shared a failed experiment.

But today I have good news.

I did it. Or at least, I feel like I did.

Initial Experiment.

For those of you who missed it, the initial experiment was a pinboard. I attempted to connect the clans and find the most common larger clans in the process. It turned into a pretty big mess.

You can read all about my strategy and see pictures of the failure in my previous article: Mongolian Clan Affiliations of the Late 15th Century.

Hierarchy Charts

It was time for take three. My third attempt to make sense out of the tangled madness. This time, I had the list from my first failed experiment to help me get started.

Stage 1:

Before I even started the chart, I decided to identify the 6 tumen of the empire after my series concludes. This gave me a base of the larger clans to work with. You can find the image that identifies them here. I used it as a base to start organizing all the other clans.

Stage 2:

Once I had the 6 tumen and the Oirat identified, I started moving down the list of clans I made in my first failed attempt. I looked up each and every one of them, digging for details from various sources to find out which of those 6 tumen or Oirat they were clearly identified with. It proved tricky in a lot of cases, and this is partly because of prolific assimilation and movement of the Mongol people at the time.

If I found a clear answer, I added their name to a piece of paper for that tumen. If I didn’t find a clear answer, I went to the text to find out who was mentioned and what they did. Then I used that to help me put them into one of the 6 tumen. Only a couple of outliers remained.

This took a long time. Finding information about most of these clans is difficult. Mongols at the time didn’t keep good records, so most of the resources are either from other nations such as China or Arabia. In these few cases, I have decided to just cut anyone not important from my series. Those who are important will be assimilated into a different clan based on their actions — i.e., who they fought for or against.

Stage 3:

Before making final decisions about which clans fell into which tumen, I then made a Powerpoint for each and every one of the people mentioned in the histories I had to work with. Each slide contained 4 characteristics:

Original Clan Name. This is based on the texts I have had to work from.

Character Name: These names are crazy, and some of them may need to be simplified when I write the books, but the names listed on these slides are their full names.

Parentage/Family: Knowing who is related to whom is an important factor in determining who the actual major players will be in the series. It will help with motivations and importance.

Notes: This characteristic includes notes on who they married, when they died, who they served, or any additional potential plot points.

I won’t spoil anything, but if you want to download it and have a look, you can do so here. Just be warned, there will be spoilers in the notes.

Stage 4:

Now, with a complete cast of characters and a better understanding of some of the clans and the roles they played during this period, I set to work creating a hierarchy chart. As I made decisions I used the information I gathered from my books and research, as well as Stages 1-3 of this process to find the best or most likely place for each of the clans to belong.

Right Wing

Right Wing of the Khalkha Dynasty

Right Wing of the Khalkha DynastyThe first chart is the Right Wing of the empire, established in the early 16th century right around the time my series concludes. Again, this chart is in no way 100% accurate. It is the best representation I could create based on the information I have been able to gather.

The Right Wing clans are probably the most tumultuous of them all. Their loyalties could swing with the breeze, so many of these will shift from one group to another.

Most of the clans listed within the Yungsiyebu were conquered by Bigirsen in the mid-15th century. His original clan is identified as Uyghur, which is also identified as Oirat. You can see where some of my confusion stemmed. However, it’s important to note that by the time of Manduul Khan, the Uyghur were strong in power and supported Manduul as khan, creating a tenuous peace with the Oirat that doesn’t last long.

The Jalair, within the Yungsiyebu clan, were quickly conquered and brought into loyalty with the Borjigin — another clan that switches sides.

The important thing to understand from this is that, though a clan is listed in one place, loyalties shift and some of them changed sides once — if not more than once — to whichever side was their best chance.

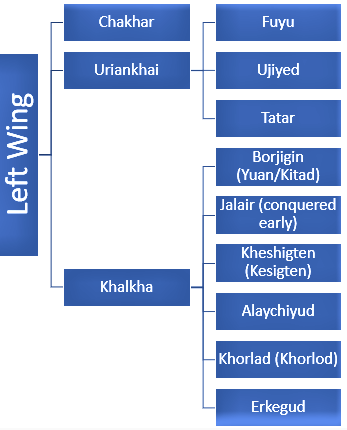

Left Wing

Left Wing of the Khalkha Dynasty

Left Wing of the Khalkha DynastyThe Left Wing was the other half of the Khalkha Dynasty that came to power in the early 16th century. The Khalkha took over as the primary dynastic ruler with the Great Khan and his heirs coming from this line and the line of Genghis Khan. Again, loyalties shifted. You will see Jalair in both the Khalkha group and the Yungsiyebu.

Likewise, the Chakhar had several subclans, but I could find no evidence of exactly which ones they ruled over.

Four Oirat

The Four Oirats — Western Mongols

The Four Oirats — Western MongolsThis group was a bit more tricky. Records of exactly which of the major clans made up the Oirat are unclear, often identifying only two or three of them. I made the most educated decisions I could based on the information I had.

The Yungsiyebu were originally part of the Oirat until Bigirsen conquered many of the southern clans and brought them under the purview of the Great Khan.

For centuries, since possibly the time of Kublai Khan, the Oirats have been at war with the Eastern Mongol clans. Many of them contested Kublai’s right to be Great Khan. Since then, they believed their heirs were the rightful heirs to the title, despite opposition from all of the Eastern clans. It wasn’t until the late 15th century that they began to lose power and some fell under the control of the Khalkha Dynasty for at least another hundred years.

~~~

In a lot of cases, the characters I outline in my slides will not even have a part in the book, and the subclans will not even have mention but will be assimilated into one of the three groups outlined above for simplicity.

But if none of the subclans will be mentioned in the Fractured Empire series, why did I bother identifying them and going to such trouble in the first place?

A good question. The primary reason is simple — I need to know which characters from my research belonged to which of the larger groups so I can portray them as accurately as possible. A lot of those characters I may not use by name in the books, but their actions will still be present, which means I have to know where their loyalties lie.

The post Mongolian Clans Affiliations of the Late 15th Century – Part II appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

June 11, 2020

Mongolian Clans Affiliations of the Late 15th Century

If there is one thing I have learned during my research for the Fractured Empire series, it’s this: Mongolian clan affiliations are a mess!

First of all, they referred to the clans as the Four and Forty — Four Oirat of the Western Empire (which was more than four, by the way) and the Forty clans of the Eastern empire (which also seemed to be more than forty).

Secondly, the spelling of clans is inconsistent. This is likely because the historical documents come from several different nations and languages from Chinese to Arab and Turkish, and sometimes Russian or German. There are also special characters we don’t use in our alphabet. Those characters don’t make sounds we would expect, which made finding the right spelling and history for any particular clan very challenging.

Thirdly, the power of a clan could rise and fall in a single battle. Some clans were once powerful, but after an utter defeat would be assimilated into the clan that conquered them. Some clans split into multiple divisions or moved all over the steppe, making it hard to pinpoint where that clan’s territory rested. Making head or tails of which clan was affiliated with which turned into a logistical, nightmarish web. I tried desperately to untangle the web in several ways.

Questions.

Before beginning, I had several questions.

Where were each of these clans located in the whole of the Mongolian Steppe? Location is important when it comes to raids, battles, and alliances.

Which subclans belonged to which of the larger clans? Elimination of as many of these clan names as possible is key for easier reading.

Which of them even were the larger clans? I needed to know who the big players were before simplifying.

How could I simplify this list of 50 clans into just a handful accurately? I don’t want my readers overwhelmed as I am at trying to figure out who belongs to who when the truth is, most of these are subclans of one larger group. I needed to know who the big players were so I could make reading and following the threads easier for my readers.

The intention was to have only a handful of clans names left to make it easier for my readers to follow along. Then, I could add a historical note at the end of the book to clarify the fact from fiction, when necessary.

It turned out to be a bigger challenge than I first expected, and my first few attempts didn’t go well.

Making a list.

This had worked for me on a number of different projects and tasks in the past, but when it came to Mongolian clans, making a list turned into an utter failure.

Creating a pinboard web.

You can walk through my progress with me in the images below.

Stage 1:

Stage 1: Pinboard of the 50 mentioned clans.

Stage 1: Pinboard of the 50 mentioned clans.First, I read through all the historical documents I had between 1454-1510. I wrote the name of every clan mentioned in those documents on a small notecard and pinned them to a board in no particular order — because let’s face it, that order was what I wanted desperately to make sense of and simplify.

Stage 2:

Stage 2: Green threads of the Four Oirat

Stage 2: Green threads of the Four OiratUsing green thread, I connected each of the clans mentioned as either directly Oirat, or to have battle affiliations with the Oirat. It didn’t look so bad, though knowing that the Eastern and Western empires constantly fought each other, I was a bit confused to see Oirat and Borjigin tied together. This connection was only temporary, though.

Stage 3:

Stage 3: Purple Thread of the southern Mongols

Stage 3: Purple Thread of the southern MongolsUsing purple thread, I attempted to connect the southern clans along the Chinese border based on clear affiliation or mentioned unity between the clans. Again, it wasn’t really too bad, and I was not surprised to see any of them connected together.

Some of the clans began presenting an issue though. For instance, the Uriankhai so far have connected to all the other major clans. I already began to see an issue with this new strategy or organization. But I carried on.

Stage 4:

Stage 4: Light blue thread of the early Borjigin

Stage 4: Light blue thread of the early BorjiginUsing a light blue thread, I connected the Borjigin to the clans they were clearly affiliated with in some way before the majority of my Fractured Empire series starts. It wasn’t so bad, but then I added a darker blue to show further Borjigin affiliations throughout the series.

And everything turned into a mess.

Stage 4: Final blue threads of the Borjigin affiliation

Stage 4: Final blue threads of the Borjigin affiliationAlmost every thread converged on the Borjigin clan. While this shouldn’t be a big surprise — this was the clan of the Great Khans after all — I still found this experiment frustrating.

Even more frustrating with my inability to use this method to better understand which clans were part of larger clans was the fact that so many of those 50 clans had no threats attaching anywhere. This experiment didn’t answer any of my questions.

But after some reflection, I finally uncovered a solution that worked for my needs … and it was tedious. More on that later!

The post Mongolian Clans Affiliations of the Late 15th Century appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

June 3, 2020

History of the Mongol Khans 1456-1468

Before I go too far, I suppose it’s fair to warn everyone that this article will contain spoilers for my series. Proceed at your own risk as I endeavor to make sense of how Manduul Khan rose to power, and how he fell.

For context on how the events in this article come to pass, I highly recommend starting by reading my previous article on the Khans of 1439-1456. Some of the characters mentioned in this article will be important players in the previous section.

Oirat Power 1456-1463

After the fall of Molon Khan, no clear historical records of a Western Mongolian Borjigin Great Yuan exist. It is believed that the Mongols were subjugated by the strength of the Four Oirat leaders. If any Great Yuan did exist, he was probably unworthy of mention or didn’t survive long enough to write about.

Most of the focus for the Mongol forces were pressed against the Chinese border against Ming forces. Several of the forces who gathered in support of Polohu, a suspected khan of the Oirats, and Molikhai the Uriankhai commander (and possibly prince?). Among those who joined them were significantly powerful generals such as Bigirsen Taishi of the Oirat Uyigud and Dogholong Taishi of the Uriankhai (and possibly a descendant of Genghis Khan’s second full brother, Hachiun).

Despite this joint venture against the Ming, beneath the surface the Mongols needed a unified leader to hold them together and keep the infighting from tearing them apart again. Hoping for control of a puppet khan, Bigirsen and Polohu united the majority of clans behind Manduul in 1463.

Manduul Khan 1463-1468

Manduul was the third son of Adai Khan, and half-brother to Taisun Khan. His other brother, Akbardish, had betrayed the Borjigin clan years before and joined the Oirat where he was eventually died. Manduul was the only known descendant of Genghis Khan remaining, so the decision to raise him to Great Yuan had been nearly unanimous. The blood of his Borjigin father and Oirat mother made him a natural selection to restore unity under one khan. In 1463, he was enthroned as Great Yuan.

In addition to becoming Great Yuan, Manduul was also given Bigirsen’s only daughter in marriage as a sign of their new bond. Yeke Qabar-tu was not an admired wife in Manduul’s eyes and their relationship was strained, at best.

Manduul Khan’s rise to power was not met with unanimous joy. Molikhai and Dogholong openly opposed Manduul. Manduul also sought vengeance for the death of the two prices Mergus and Molon — also his nephews from his older half-brother Taisun. Since Dogholong was responsible for the death of Mergus, and Molikhai responsible for the death of Molon, Manduul united the rest of the clans — Oirat included — and launched an attack against the Tatar and Uriankhai. His superior force met the clans of the 7 Tumed, killed Molikhai and Dogholong, and subjugated the clans of the 7 Tumed.

At some point amongst this, Manduul married Mandukhai — his second wife, possibly from the Onguud of the 7 Tumed as a way of ensuring peace.

Before his death, Akbardish’s son sired a son of his own. In my previous article, I mention how this child was sent away for protection from the wrath of Esen. Manduul discovered this boy, Bayan, still lived. He brought Bayan under his wing and treated him as his own son. In 1464/1465, Manduul named Bayan the Golden Prince, Bolkhu Jinong.

Now, with two wives, the subjugation of the Four and Forty (clans of the Oirat and 6 Tumens), and an heir whom he believed would produce many more children to strengthen the Borjigin line, Manduul settled in Mongke Bulag where he would remain.

Bigirsen, appearing ever loyal to Manduul Khan, send his protege Issama Taishi to Mongke Bulag. Issama hailed from the same Oirat clan as Bigirsen. He quickly found a distaste for Bayan Bolkhu Jinong. After one of Bayan’s dependants (possibly a slave, as Bayan had no other dependants to speak of in a more modern sense), confessed to Manduul Khan that Bayan had evil designs against the khan and sought to steal his wife. Manduul loved and trusted Bayan — almost to a fault — and refused to believe the slander against his heir. In retaliation, Manduul ordered the slave’s lips and nose removed, then had him put to death.

Issama, however, found this as an opportunity to further press division between the two men. His goals are unclear, but some believe he hoped to finish what Esen started years ago — to wipe out the remaining Borjigin heirs. Doing so would leave the title of Great Yuan up for grabs to whichever man was strong enough to seize and hold it.

Before setting speaking to the khan, Issama poisoned Bayan’s mind against Manduul, planting seeds of doubt. The details on this are, again, unclear, but there is no doubt that Issama’s plan succeeded. Bayan became more uncertain of Manduul’s intentions. When the moment was right, Issama went before Manduul and confessed the same tale as the slave — that Bayan was plotting behind his back and preparing to steal his wife away.

Manduul felt more suspicious now that the story had been repeated twice, and once by a trusted Taishi. He sent several rather terse messages to Bayan, and in the end, Bayan fled Manduul’s wrath to seek out safety elsewhere. Bayan went first to Bigirsen, hoping to gain the support of the Oirats. Instead, he fled for his life once more, forced into the desert where he was finally chased down and killed by Issama’s men.

Overcome with anger and despair, Manduul also passed away during this period. Some histories account for his death in 1467, 1468, and 1470. Considering what comes next, it is safe to assume his death occurred in late 1468.

Thus ended the reign of Manduul Khan, and possibly the Borjigin line…

*Historical information used for the purposes of my research comes from renowned Mongolia Historian Jack Weatherford, and a rather detailed book compiling multiple resources, titled History of the Mongols: The Mongols Proper and the Kalmuks.

The post History of the Mongol Khans 1456-1468 appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.

June 2, 2020

History of the Mongol Khans 1439-1456

dothing says “I’m moving on” quite like starting a new series. My next endeavor, the Fractured Empire series, takes place in late 15th-Century Mongolia. It shares the story of a kingdom torn apart by men, and how one strong woman helps bring it back to glory.

As I research my Fractured Empire series, I will dissect some of the early rivalries to understand the depth of ancient grudges among the Mongol peoples. They were well known for their ability to fight battles, and often those wars were waged between each other.

After the fall of Genghis Khan, princes from his bloodline began fighting each other for control. At first, this rivalry was fairly mild, but by the time of Kublai Khan (and after), those feuds ran deeper. Ancient grudges fueled their infighting until all the work Genghis Khan had accomplished fractured and fell into ruins.

The Four Oirat divided the clans in half — East vs. West. While it’s actually a lot more complicated than that, for the sake of simplicity, we will keep the concept of the division here.

The Four Oirat (Western Mongols) rose to their strongest power in the early 15th century as the line of Genghis Khan began to lose power and dwindle.

Taisun (Taissong) Khan 1439-1452

Taisun was the oldest of three sons — Taisun, Akvardsci, and Manduul (half brother from an Oirat mother) — born to Adai Khan. Taisun Khan came from a long line of Borjigin (Eastern Mongols) descended from Genghis Khan.

After the death of his father, Adai Khan, at the hands of an Oirat taishi, Taisun was selected at the age of 18 by a Choros (Oirat subclan) taishi, Esen, to be the next Great Yuan (also known as Great Khan). Esen’s sister Altaghaltschin married Taisun to solidify the unity between the Eastern and Western Mongols.

For several years after, Esen and Taisun launched successful campaigns against the Chinese emperor. They worked in harmony and the clans knew a tenuous peace for the first time in centuries — with all of their military force focused more on external conflict than internal conflict.

When Esen’s sister (wife of Taisun) had a son, Esen asked Taisun to name that boy (Molon) prince and heir. Taisun refused. While the reasons for that refusal are a bit cloudy, some believe Taisun saw more promise in his son Merguschas, born from his wife Ssamar Taigho (clan unknown), even though he was younger than Molon. Others believe Taisun feared Esen would kill him the moment Molon was old enough to be named Great Yuan. Esen probably hoped to not only gain control of young heir and future khan through his blood ties but to finally unite the Eastern and Western Mongols under a khan from Borjigin-Oirat descent. However, Taisun’s refusal (and subsequent return of Esen’s sister and Molon to her father) enraged Esen. Feeling betrayed by the man he considered his ally and brother through marriage, he attacked Taisun Khan and killed him.

Esen Khan 1452-1454

After the death of Taisun, Esen proclaimed himself Great Yuan without calling for the support of the clans. He assumed control through force, using his superior military forces to smash any who opposed him. His grab at power and a title that belonged to the Borjigin (which he was not descended from) caused division even among his own ranks.

Furious that any of the clans would stand against him, and still bitter about Taisun’s betrayal, Esen systematically killed everyone he could get his hands on who had direct ties to the Borjigin line. He welcomed the men to his camp, a custom that promised peace while they were in his camp. Esen then welcomed Borjigin men into his ger. Thinking they were safe under guest rights (as was their custom), they entered.

But Esen had a trick up his sleeve. He had his men dig out a hole in the floor and cover it with rugs. As the Borjigin men entered, the rug would collapse, trap them into the hole, and they would then be killed while trapped. Among those who fell prey to his trickery was Akvardsci — Taisun’s brother. Akvardschi abandoned his brother and took sides with the Oirat early on, but he wasn’t exactly bright. When he was presented as the next Great Yuan, the danger of his idiocy became very real. He was tricked into naming Esen his heir, despite having a son, Kharghotsok. As they celebrated Esen’s new title, all of Akvardschi’s family was welcomed into the tent under guest rights. All who entered were swiftly killed.

Not long before this brutal murder of the Borjigin men, Kharghotsok married Esen’s daughter, Ssetsek Beidschi. Esen wanted her to remarry after the death of Kharghotsok, but she refused to do so without proof of his death. Meanwhile, scared for the life of her young son after the murder of her husband at her father’s hands, Ssetsek Beidschi begged her grandmother Samur (Esen’s mother) to help her protect her son Bayan. Samur then repeatedly convinced Esen that the Bayan was actually a girl and not a boy so that he would not fear the boy growing up to replace him. These attempts to deceive Esen do not last long, and Samur was forced to send Bayan away to the Western Mongols for protection from Esen’s wrath.

Between Esen’s failure to destroy the Chinese empire, the murder of two Great Yuan’s and ties to their line, and the seizure of the title of Great Yuan without proper support, even his own Oirat clans began to distrust him. By 1454, the people of the East and West Mongols revolted against Esen and killed him. This complete betrayal of the people would follow the Oirat people long after his death.

Merguschas 1454

Taisin’s youngest son and named hair Merguschas was raised by his mother as Great Yuan. She put him in a box and rode to war against the Oirats to exact revenge. Though the battle was victorious, Merguschas did not survive long after. His reign was short and he was killed by men of the 7 Tumed.

Molon Khan 1454-1456

At this point in history, dates really get confusing. Leaders who are enthroned one year could have died years before. From here, I make my assumptions based on the most common denominator.

Some records say that Molon (Taisun’s eldest son) was named Great Yuan in 1452. Others say it wasn’t until after the fall of Esen Khan in 1454. Considering Esen’s rage against the Borjigin line at the end of his life, I think it’s safe to assume Molon did not come to power until after his death. Especially if his brother Merguschas was raised even if temporarily as Great Yuan. This would also make Molon 17 when he becomes Great Yuan, barely old enough to lead.

At a young age, Molon was sent to his grandfather Tsabdan along with his mother. Tsabdan raised Molon until the age of 16, protecting him from Esen and the assaults against the Borjigin. In 1453, Tsabdan was murdered by a man of the Khorlad clan. That man took Molon and turned him into a slave. For a short period thereafter, the Khorlad clan fell into poor luck and many blamed it on the enslavement of the heir of the Borjigin title.

Molon was released and sent to Molikhai Ong, a Tatar commander. The people rejoiced and immediately set Molon on a horse with a golden scepter and named him “Little King.” He was married to a beautiful young princess named Monggutsar.

Not long after being enthroned, Molon Khan heard hints from an advisor, Khodobagha, that his rescuer and trusted ally Molikhai envied his young wife and was marching an army against the khan to capture her. Molon found this hard to believe, but he sent a scout to investigate. Molikhai was, at the time, hunting. The scout confused dust from the hunt for dust from the army and he rushed back to report to the khan. With no other choice, Molon pulled up camp and rode out to greet his former ally.

Meanwhile, Khodobagha went to Molikhai and reported that the khan’s army was coming to crush him. Molikhai didn’t believe it at first, because he and Molon had never had a quarrel with each other and had mutual respect. He went himself to see and when he crested a hill spotted the khan’s army riding his way. In desperation, he prepared his own forces, prayed to the gods for the best outcome for the people, and went to war against Molon Khan.

Molon was killed in the battle(1456). Molikhai was wrought with grief, and in that grief, heard the wails of Molon’s young wife accusing Khodobagha of setting up this deception that anyone was after her. Shocked and angered, Molikhai repented his sin against Molon, then cut out Khodobagha’s tongue and killed him.

Thus ended Molon Khan’s reign.

*Historical information used for the purposes of my research comes from renowned Mongolia Historian Jack Weatherford, and a rather detailed book compiling multiple resources, titled History of the Mongols: The Mongols Proper and the Kalmuks.

The post History of the Mongol Khans 1439-1456 appeared first on Starr Z. Davies.