R.B. Lemberg's Blog, page 32

July 10, 2012

Please spread the word: Clockwork Phoenix 4 Kickstarter now live

------------------------------------

Originally posted by

time_shark

at Please spread the word: Clockwork Phoenix 4 Kickstarter now liveI am very pleased, thrilled, chuffed (and perhaps even a little nervous) to announce that Anita and I have launched a Kickstarter campaign in hopes of raising the funds to assemble and publish a fourth volume of Clockwork Phoenix. It has a convenient Tiny URL: http://tinyurl.com/CP4antho

time_shark

at Please spread the word: Clockwork Phoenix 4 Kickstarter now liveI am very pleased, thrilled, chuffed (and perhaps even a little nervous) to announce that Anita and I have launched a Kickstarter campaign in hopes of raising the funds to assemble and publish a fourth volume of Clockwork Phoenix. It has a convenient Tiny URL: http://tinyurl.com/CP4anthoWe very proud of the first three anthologies and we want to read for a fourth; but it's absolutely clear — even as successful as those first three books were, with the great reviews and award nominations our authors received — in this economic environment, if we want to continue making these books at the standard we want to hold them to, we have to crowdsource the funding and publish the next one ourselves.

If the project is a go, we'll open to submissions in September and aim for a June 2013 release.

I could go on about all the rewards we came up with and what we hope to accomplish, but it's probably much simpler if you just click the link (here! here!) and have a look at the Kickstarter page, where it's all spelled out.

Please help us spread the word! (And please feel free to repost this entry if you like.)

July 9, 2012

On Bardugo’s Tsarpunk, Worldbuilding, and Historical Linguistics

Reflecting on Leigh Bardugo’s use of Russian in Shadow and Bone, I have made some comments to friends who asked to hear more. For context: this is the book (link goes to Goodreads); this is a positive review of the book that raised the questions that prompted this entry; this is a trustworthy negative review. Context about myself for those who do not know me: born in Ukraine, native speaker of Russian, a Jew, immigrant living in the US, linguist.

Specific languages arise and are developed through unique historical, and historical linguistic processes. This sounds trivial, but let me elaborate for a second – because it is CRUCIAL to understand some of this if you want to make a good job of incorporating existing world languages into your secondary-world fiction. Sarah Monette gives a good background to the issue in The Moss-Troll problem - how do we construct secondary worlds that are internally consistent?

“the problem … [is] one that a writer of secondary-world fiction encounters frequently. … You can’t, for instance, say something is as basic as the missionary position in a world without missionaries. What about saying something is as swift and sharp as a guillotine’s blade? Well, did Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin exist in this world?”

Drawing on real-world languages in a secondary world raises the same issues. If you want thoughtful worldbuilding rather than just grabbing stuff for garnish and exoticization, you should ask yourself, “This is a secondary world. How did languages I am describing here arise, and how do I account for them sounding just like planet Earth’s language X?” It is a crucial question to ask because specific languages arise and are developed through unique historical, and historical linguistic processes.

Let me start with a fairly simple and straightforward example. The word tsar (царь) comes from Caesar, and was adopted into Russian through Gothic; Goths in turn borrowed it from Latin. [1] Grisha is a diminutive of Grigorii, a Christian name of Greek origin (Γρηγόριος ‘wakeful’) ; Christian names in Russian originate from Byzantium. Unless you are writing an alternative history incorporating old Julius, Rome, Germanic tribes interacting with Rome, Byzantium and early Christianity [2], the word tsar and the name Grisha should NOT appear in your secondary world fantasy. [3] Those who are going to tell me “but it’s just fantasy!!” are wrong. It’s that simple. Within your secondary world, unless you are writing satire, things should make internal sense. If there is no Caesar, there is no tsar. That word could not arize independently of its context.

Onwards. When it comes to sound changes, some languages and language families are more conservative, while others are more innovative (those words are not value judgments – they are terms pertaining to phonetics and phonology). For example, the Semitic language family and the Indo-European language family are similar in age, but the Semitic root tends to be significantly more stable (due to the placement of the vowels in the root and some other factors) than the Indo-European root. Different branches of Indo-European are differently innovative when it comes to the sound system. Some of it has to do with geographical spread, e.g isoglosses such as the kentum/satem isogloss, some with the different reflexes of laryngeals, etc, etc.

Within the Indo-European language family, the Slavic language family underwent changes that are in themselves quite striking. Some of those changes are common to the whole Slavic family before it split, others are specific to the North vs South divide, yet others to East, West, South divide, and yet others to individual languages within these groups.

Common Slavic, a language we postulate was spoken by the Slavs around 4-6 centuries CE, underwent a number of important innovations that differentiate it from its closest relative, Baltic. [4] (DO NOT look this up in Wikipedia, it presents incorrect or incomplete information on Slavic historical phonetics and phonology.)

One of the first innovations introduced was the so-called law of rising sonority, which basically meant that syllables were reformed to always end on a sound of higher sonority. Thus, syllables that were consonant-vowel-consonant very roughly wanted to become consonant-vowel. They did it for example by dropping the last consonant in each syllable (so things like Common Slav. sūnus ‘son’ became synǔ), and by other, more convoluted processes. This was a phonetic catastrophe of major proportions that dragged other changes – monophtongization of diphtongs, palatalizations, etc, etc, etc. To show you exactly how many chronologically ordered phenomena could be involved in a generation of simple words, let’s look at poor tsar again.

Step 1. Julis Caesar exists and is a significant historical personage – also in your secondary world (somehow). It’s his name, after all.

Step 2. The Latin is borrowed into Gothic. You have to have Goths or at least some kind of Germanic-speaking peoples there for the sake of your sound system’s consistency. Gothic form is kaisar.

Step 3. Goths come in contact with the Slavs and the word kaisar is borrowed.

Step 4a. Slavs experience the law of rising sonority. The vowel a is higher in sonority than i, so a syllable kai is no longer permitted to exist.

Step 4b. Oh no! Because of 4a, the Slavs experience Monophtongization of Diphtongs!!! ai > ĕ, thus kaisar > kĕsar’.

Step 5. Second (regressive) palatalization occurs for velars followed by the new vowel ĕ, which is to say k mutates to ts and thus kĕsar’ > tsesar’

Step 6. tsesar’ gets shortened to ts’sar’ and from there to tsar’.

So… if all this did not happen in your world and your language(s), what is tsar (and tsaritsa) doing there?

After Common Slavic split into groups and then individual languages, each Slavic language continued to innovate in the sound system. Many Slavic languages are mutually intelligible, and even introduced similar innovations after the split (continuing the changes started by the law of rising sonority, for example) – but despite their striking closeness, each Slavic language developed differently.

Without lecturing you on – for example – the fall of the jers, and other things that go into the serious study of Slavic and Russian historical phonetics and phonology, let me assure you that odinakovost‘ could not have arisen as a word in any language but Russian. It is inconceivable. (But I can explain exactly how, over hundreds of years of historical linguistic developments, a word with that shape could develop in Russian).

There is no way a non-Russian Slavic language would develop independently and be identical to Russian in phonetics/phonology and word formation.

Hence, “This is not Russia, this is Ravka” is completely fallacious. If a word like odinakovost’ exists there, it is Russia, with linguistic processes lifted intact. There is no way this derivation could have happened independently in a secondary world. If you are doing this, you have not done good worldbuilding; you appropriated for garnish without stopping to think. What you constructed makes no sense within the context of your own secondary world.

So, say, you have in your secondary world a Slavic-inspired country with the following parameters: the culture has never come in contact with Goths, Vikings, and Balts; the culture never underwent Christianization, and has not come in contact with the Holy Roman Empire, either Western or Eastern. There are no Jews whatsoever, either of Byzantine origin (no Byzantium), or of Ashkenazi origin, because if Christianity did not exist and persecute Jews, Ashkenazi Jews would have no reason to flee Western Europe and seek refuge in the Slavic lands. So what is, according to me (bag of salt! bag of salt!) an acceptable thing to do in this situation, language-wise?

Well, I think most importantly you should realize that this kind of complexity is involved, in the first place.

In other words, you should do your research, especially if you are not a native speaker and are taking things from a culture and language not your own, for your own fun and profit. [5]

Next, probably look at Common Slavic, which had no or limited contact with Christianity – and use Common Slavic forms. Consult an etymological dictionary to exclude words of Germanic, Baltic, Greek, Latin, and other undesirable origins. Perhaps if you have the training to do so, derive a sibling Slavic language from the reconstructed Common Slavic. Or perhaps even use Old Russian forms, but for the sake of old Julius and the Emperor Constantine, DON’T incorporate Latin and Greek words that have nothing to do with the world you built, because there is no way they could have landed there, because specific languages arise and are developed through unique historical, and historical linguistic processes.

————————-

[1] – According to Vasmer. Another theory is that it was borrowed from Greek kaisar, but the Latin > Gothic > Slavic route is the most likely.

[2] Bardugo does not seem to have Christianity in her book, but she has saints complete with a Latin-looking designation for them (Sankt) which makes little sense to me.

[3] Similarly, names like Alexei (Christian, Greek) and Mikhael (Biblical, Hebrew through Greek) could not exist in Slavic without Byzantium and Christianity (the name Mikhael also could not have existed without Hebrew and Jews).

[4] – I am not going to go into the Proto-Balto-Slavic continuum debate due to lack of time and space; and I am not going to discuss Indo-European either, because we’ll be here forever, but I can speak about this in person sometime if there is interest).

[5] – I am not going to get into the question of “who owns the language”, and whether native speakers and heritage speakers get more leeway when using their OWN languages to write in English. It is definitely a different situation than what we have with Bardugo’s, and opinions vary here. For myself and myself only, a multilingual immigrant writing in Slavic- and Semitic- inspired secondary world settings, I do not feel that I get more leeway as a native speaker; but this is a more complex issue than I can get into, within the scope of this entry.

[Warning: if you are feeling compelled to ask "who the heck cares?" and/or tell me I am taking this way too seriously, the answers are: I care, and indeed I am taking this seriously. This is my space. If you feel the urgent need to troll, be advised that you should do so elsewhere, or be subjected to the Firebird Flamethrower.]

Originally published at RoseLemberg.net. You can comment here or there.

July 2, 2012

Between the Mountain and the Moon

My queer mythic poem in three acts and a coda, “Between the Mountain and the Moon,” is up at Strange Horizons!

It was written for Izlinda Hani Jamaluddin as a part of the Magick4Terri auction.

It contains one of my favorite-ever lines, ” Every girl [...]

followed by suitors springing everywhere like moths from larvae”

Also relevant: “The Making of Between the Mountain and the Moon.”

Originally published at RoseLemberg.net. You can comment here or there.

June 26, 2012

Two New Reviews – HWC and MoC

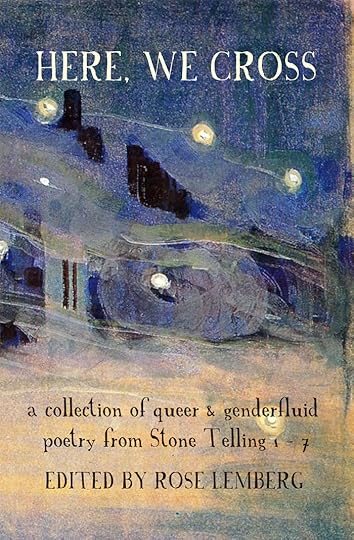

A wonderful, thoughtful review of Here, We Cross by Brit Mandelo (Tor.com):

As a whole, I find Here, We Cross to be a vital book—thriving and full of life, putting to words intense emotion as well as the internal workings of identity and self. The focus on genderqueer and genderfluid poetry is a particular joy for me as a reader; these are voices still underrepresented in the larger literary conversation, but in this book they are a force, a majority, that must be considered and acknowledged. There’s also a real pleasure to be had in reading a book, cover-to-cover, that is filled with explicitly queer, trans*, neutrois, and asexual voices, all telling pieces of their stories and bringing to vivid life what it means to be them—and therefore, what it means for them to be, what steps must be taken to forge and protect a sense of identity.

Many poems are analyzed in depth, including Mary Alexandra Agner’s “Tertiary,” Nancy Sheng’s “Inner Workings”, Amal El-Mohtar’s “Asteres Planetai,” and Shira Lipkin’s “The Changeling’s Lament.”

Here, We Cross is available for purchase at Amazon.

A great review of the Moment of Change, by Francesca Forrest (Versification):

A champion of diversity, Lemberg has chosen poems that represent the unruly, ungeneralizable expanse of human female experience. There’s no one agenda here: there are angry poems, but also joyful ones; there are poems of childhood and old age, poems of hope and despair. There are poems in which gender is central and others in which it is peripheral. If there’s a unifying theme, it’s the importance of finding one’s voice and then using it.

Francesca praises my ordering of the poems, but accolades here are due to other members of Team Stone Telling, Shweta Narayan and Jennifer Smith, who helped me figure out the sequencing!

Moment is available from Aqueduct and from Amazon.

Originally published at RoseLemberg.net. You can comment here or there.

June 22, 2012

I am going to take some days off here. I will not be post...

June 19, 2012

Here, We Cross - the Queer Chapbook

stonetellingmag

; this is an indication of how unwell I've been. So I thought I'd crosspost here also. It's a wonderful book and I am very proud of it.

stonetellingmag

; this is an indication of how unwell I've been. So I thought I'd crosspost here also. It's a wonderful book and I am very proud of it.---------------------------------

Originally posted by

rose_lemberg

at Here, We Cross - the Queer ChapbookDear Friends of Stone Telling,

rose_lemberg

at Here, We Cross - the Queer ChapbookDear Friends of Stone Telling,We've both been under the weather for a long time, which explains my utter failure to post about this to the community. But: "Here, We Cross," a chapbook of queer poetry from issues 1-7 of Stone Telling, is real and in the world. I am used to calling it a chapbook, but it's more than a chapbook - Here, We Cross is a beautiful perfect-bound book, all 94 pages of it lovingly put together by

dormouse_in_tea

and myself.

dormouse_in_tea

and myself.It really is gorgeous (trust me, I am a perfectionist). It is available for purchase from Amazon for the momentous sum of $10. Depending on how well this one does, there might be others in the future.

The lineup!

Alex Dally MacFarlane – Sung Around Alsar-Scented Fires

Nancy Sheng – Inner Workings

Michele Bannister – Seamstress

Jack H. Marr – Lunectomy

Shira Lipkin – The Changeling’s Lament

Dominik Parisien – In His Eighty-Second Year

Bogi Takács – The Handcrafted Motions of Flight

Hel Gurney – Hair

Mary Alexandra Agner – Tertiary

Amal El-Mohtar – Asteres Planetai

Jeannelle Ferreira – Ardat-Lilî

Mari Ness – Encantada

Lisa Bradley – we come together we fall apart

Samantha Henderson – The Gabriel Hound

Alexandra Seidel – A Masquerade in Four Voices

Sonya Taaffe – Persephone in Hel

Sergio Ortiz – Rain and Sound

Sonya Taaffe – The Clock House

Peter Milne Greiner – The Earth Has Rings

Adrienne J. Odasso – Parallax

Tori Truslow – Terrunform

Peer G. Dudda – Sister Dragons

June 18, 2012

Olivia and the Experiments

Here is the description:

Olivia's out of school for the summer. What better way to fill the days than to build a cyclotron or run DNA through a blender to study its hereditary nature? Doing it with your friends!I just think it is incredibly cool - hence signal boosting. The Kickstarter page is here.

I will write three stories showing Olivia and her friends adventuring with science, technology, engineering, and math. The stories will emphasize Olivia's motto that STEM subjects can always be figured out, if not immediately understood. Additionally, the stories will incorporate under-emphasized aspects of science: collaboration, creativity, and its application for improvement of the human condition. Each story will include a picture of a LEGO model of the apparatus used by Olivia during the story.

June 8, 2012

The Moment of Change reviewed at Tor.com

Brit Mandelo has reviewed the Moment of Change at Tor.com. I cannot but admire this review, and not because it is so positive. I have long admired Brit’s ability to write lucidly and powerfully about speculative fiction (as can be evidenced in her series of Tor.com essays on Queering SFF and Reading Joanna Russ, as well as her recent Aqueduct book We Wuz Pushed: Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-Telling). In this review, Brit Mandelo beautifully articulates and analyzes my vision for the anthology:

First, I will say that there is a great deal of anguish in this book: the anguish of silenced voices, of the belittled and ignored, the anguish of suffering as well as the anguish of circumscribed success. However, there is also a sort of wild, free-wheeling determination bound up in and spurred on by that anguish—a desire for freedom, a desire for recognition, a desire for the moment in which the poem transcends mere text and speaks truths. This tonal resonance—the conflict between themes of anguish/containment and freedom/wildness—is struck by the opening poem, Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Werewomen,” and continues to resound throughout the entire collection, scaling up and down in intensity but always somehow present as a shapely concern within the poems and their organization.

Another thing that sets the tone for the text is the fact that the book opens with, and is titled from, an Adrienne Rich poem about the nature of poetry: the poet, poem, and the moment of change in which the poem exists are all tangled up together as one object, as one thing. This tri-natured sense of poetry informs and guides The Moment of Change, where poems are the poets writing them and vice versa, where the consciousness of feminism and intersectional identity blends with the written form to capture a moment of shifting—a moment of change. As such, most of these poems have a sense of movement; they are not simply lovely snapshots with an argument made via resonance, but have narrative, emotional pressure, and a sense of development or epiphany.

I am tempted to quote the whole review, but you should, if you are so inclined, head over to Tor.com and read it there instead.

Originally published at RoseLemberg.net. You can comment here or there.

May 31, 2012

Locus Podcast, and Review

Emily Jiang and I talk about speculative poetry, diversity, multilingualism, and music in the Locus Poetry podcast.

And Erik Amundsen reviews the seventh issue of Stone Telling at Versification.

Originally published at RoseLemberg.net. You can comment here or there.

May 29, 2012

For all you insomniacs and lovers of catabasis

Translation is floating on the screen, but this page has a better bilingual setup.