Robert B. Reich's Blog, page 145

July 25, 2011

Vicious Cycles: Why Washington is About to Make the Jobs Crisis Worse

We now live in parallel universes.

One universe is the one in which most Americans live. In it, almost 15 million people are unemployed, wages are declining (adjusted for inflation), and home values are still falling. The unsurprising result is consumers aren't buying — which is causing employers to slow down their hiring and in many cases lay off more of their workers. In this universe, we're locked in a vicious economic cycle that's getting worse.

The other universe is the one in which Washington politicians live. They are now engaged in a bitter partisan battle over how, and by how much, to reduce the federal budget deficit in order to buy enough votes to lift the debt ceiling.

The two universes have nothing whatever to do with one another — except for one thing. If consumers can't and won't buy, and employers won't hire without customers, the spender of last resort must be government. We've understood this since government spending on World War II catapulted America out of the Great Depression — reversing the most vicious of vicious cycles. We've understood it in every economic downturn since then.

Until now.

The only way out of the vicious economic cycle is for government to adopt an expansionary fiscal policy — spending more in the short term in order to make up for the shortfall in consumer demand. This would create jobs, which will put money in peoples' pockets, which they'd then spend, thereby persuading employers to do more hiring. The consequential job growth will also help reduce the long-term ratio of debt to GDP. It's a win-win.

This is not rocket science. And it's not difficult for government to do this — through a new WPA or Civilian Conservation Corps, an infrastructure bank, tax incentives for employers to hire, a two-year payroll tax holiday on the first $20K of income, and partial unemployment benefits for those who have lost part-time jobs.

Yet the parallel universe called Washington is moving in exactly the opposite direction. Republicans are proposing to cut the budget deficit this year and next, which will result in more job losses. And Democrats, from the President on down, seem unable or unwilling to present a bold jobs plan to reverse the vicious cycle of unemployment. Instead, they're busily playing "I can cut the deficit more than you" — trying to hold their Democratic base by calling for $1 of tax increases (mostly on the wealthy) for every $3 of spending cuts.

All of this is making the vicious economic cycle worse — and creating a vicious political cycle to accompany it.

As more and more Americans lose faith that their government can do anything to bring back jobs and wages, they are becoming more susceptible to the Republican's oft-repeated lie that the problem is government — that if we shrink government, jobs will return, wages will rise, and it will be morning in America again. And as Democrats, from the President on down, refuse to talk about jobs and wages, but instead play the deficit-reduction game, they give even more legitimacy to this lie and more momentum to this vicious political cycle.

The parallel universes are about to crash, and average Americans will be all the worse for it.

July 22, 2011

Why Medicare Is the Solution -- Not the Problem

Not only is Social Security on the chopping block in order to respond to Republican extortion. So is Medicare.

But Medicare isn't the nation's budgetary problems. It's the solution. The real problem is the soaring costs of health care that lie beneath Medicare. They're costs all of us are bearing in the form of soaring premiums, co-payments, and deductibles.

Medicare offers a means of reducing these costs — if Washington would let it.

Let me explain.

Americans spend more on health care per person than any other advanced nation and get less for our money. Yearly public and private healthcare spending is $7,538 per person. That's almost two and a half times the average of other advanced nations.

Yet the typical American lives 77.9 years – less than the average 79.4 years in other advanced nations. And we have the highest rate of infant mortality of all advanced nations.

Medical costs are soaring because our health-care system is totally screwed up. Doctors and hospitals have every incentive to spend on unnecessary tests, drugs, and procedures.

You have lower back pain? Almost 95% of such cases are best relieved through physical therapy. But doctors and hospitals routinely do expensive MRI's, and then refer patients to orthopedic surgeons who often do even more costly surgery. Why? There's not much money in physical therapy.

Your diabetes, asthma, or heart condition is acting up? If you go to the hospital, 20 percent of the time you're back there within a month. You wouldn't be nearly as likely to return if a nurse visited you at home to make sure you were taking your medications. This is common practice in other advanced countries. So why don't nurses do home visits to Americans with acute conditions? Hospitals aren't paid for it.

America spends $30 billion a year fixing medical errors – the worst rate among advanced countries. Why? Among other reasons because we keep patient records on computers that can't share the data. Patient records are continuously re-written on pieces of paper, and then re-entered into different computers. That spells error.

Meanwhile, administrative costs eat up 15 to 30 percent of all healthcare spending in the United States. That's twice the rate of most other advanced nations. Where does this money go? Mainly into collecting money: Doctors collect from hospitals and insurers, hospitals collect from insurers, insurers collect from companies or from policy holders.

A major occupational category at most hospitals is "billing clerk." A third of nursing hours are devoted to documenting what's happened so insurers have proof.

Trying to slow the rise in Medicare costs doesn't deal with any of this. It will just limit the amounts seniors can spend, which means less care. As a practical matter it means more political battles, as seniors – whose clout will grow as boomers are added to the ranks – demand the limits be increased. (If you thought the demagoguery over "death panels" was bad, you ain't seen nothin' yet.)

Paul Ryan's plan – to give seniors vouchers they can cash in with private for-profit insurers — would be even worse. It would funnel money into the hands of for-profit insurers, whose administrative costs are far higher than Medicare.

So what's the answer? For starters, allow anyone at any age to join Medicare. Medicare's administrative costs are in the range of 3 percent. That's well below the 5 to 10 percent costs borne by large companies that self-insure. It's even further below the administrative costs of companies in the small-group market (amounting to 25 to 27 percent of premiums). And it's way, way lower than the administrative costs of individual insurance (40 percent). It's even far below the 11 percent costs of private plans under Medicare Advantage, the current private-insurance option under Medicare.

In addition, allow Medicare – and its poor cousin Medicaid – to use their huge bargaining leverage to negotiate lower rates with hospitals, doctors, and pharmaceutical companies. This would help move health care from a fee-for-the-most-costly-service system into one designed to get the highest-quality outcomes most cheaply.

Estimates of how much would be saved by extending Medicare to cover the entire population range from $58 billion to $400 billion a year. More Americans would get quality health care, and the long-term budget crisis would be sharply reduced.

Let me say it again: Medicare isn't the problem. It's the solution.

[This is drawn from a post I did in April, also before current imboglio]

The Only Social Security Reform Worth Considering: Raising the Ceiling on Income Subject to It

The very idea that Social Security might be on the chopping block in order to pay the ransom Republicans are demanding reveals both the cravenness of their demands and the callowness of the opposition to those demands.

In a former life I was a trustee of the Social Security trust fund. So let me set the record straight.

Social Security isn't responsible for the federal deficit. Just the opposite. Until last year Social Security took in more payroll taxes than it paid out in benefits. It lent the surpluses to the rest of the government.

Now that Social Security has started to pay out more than it takes in, Social Security can simply collect what the rest of the government owes it. This will keep it fully solvent for the next 26 years.

But why should there even be a problem 26 years from now? Back in 1983, Alan Greenspan's Social Security commission was supposed to have fixed the system for good – by gradually increasing payroll taxes and raising the retirement age. (Early boomers like me can start collecting full benefits at age 66; late boomers born after 1960 will have to wait until they're 67.)

Greenspan's commission must have failed to predict something. What?

Inequality.

Remember, the Social Security payroll tax applies only to earnings up to a certain ceiling. (That ceiling is now $106,800.) The ceiling rises every year according to a formula roughly matching inflation.

Back in 1983, the ceiling was set so the Social Security payroll tax would hit 90 percent of all wages covered by Social Security. That 90 percent figure was built into the Greenspan Commission's fixes. The Commission assumed that, as the ceiling rose with inflation, the Social Security payroll tax would continue to hit 90 percent of total income.

Today, though, the Social Security payroll tax hits only about 84 percent of total income.

It went from 90 percent to 84 percent because a larger and larger portion of total income has gone to the top. In 1983, the richest 1 percent of Americans got 11.6 percent of total income. Today the top 1 percent takes in more than 20 percent.

If we want to go back to 90 percent, the ceiling on income subject to the Social Security tax would need to be raised to $180,000.

Presto. Social Security's long-term (beyond 26 years from now) problem would be solved.

So there's no reason even to consider reducing Social Security benefits or raising the age of eligibility. The logical response to the increasing concentration of income at the top is simply to raise the ceiling.

[This post is drawn from one I posted in February — before Social Security was as on the chopping block]

July 20, 2011

The Shameful Murder of Dodd Frank

Happy Birthday Dodd Frank,

Happy Birthday to you,

You've lost all your muscle,

And your teeth are gone, too.

One full year after the financial reform bill spearheaded through Congress by Christopher Dodd and Barney Frank was signed into law, Wall Street looks and acts much the way it did before. That's because the Street has effectively neutered the law, which is the best argument I know for applying the nation's antitrust laws to the biggest banks and limiting their size.

Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner says the financial system is "on more solid ground" than prior to the 2008 crisis, but I don't know what ground he's looking at.

Much of Dodd-Frank is still on the drawing boards, courtesy of the Street. The law as written included loopholes big enough to drive bankers' Lamborghini's through — which they're now doing.

What kind of derivatives must be traded on open exchanges? What are the capital requirements for financial companies that insure borrowers against default, such as AIG? How should credit rating agencies be funded? What about the much-vaunted Volcker Rule requiring that banks trade their own money if they're going to gamble in the stock market – how should their own money be defined? What "stress tests" must the big banks pass to maintain their privileged status with the Fed?

The short answer: whatever it takes to maintain the Street's profits and perquisites.

The law included a one-year delay, ostensibly to give regulators time to iron out these sorts of details. But the real purpose of the delay, it's now obvious, was to give the Street time to expand the loopholes and fill the details with pablum — when the public stopped looking.

Since Dodd Frank was enacted a year ago, Wall Street has spent as much – if not more – on lobbyists and political payoffs designed to stop the law's implementation than it did trying to kill off the law in the first place. The six largest banks spent $29.4 million on lobbying last year, according to firm disclosures — record spending for the group. This year they're on track to break last year's record.

According to the Center for Public Integrity, the Street and other financial institutions engaged about 3,000 lobbyists to fight Dodd-Frank – more than five lobbyists for every member of Congress. They've hired almost the same number to delay, weaken, or otherwise prevent its implementation.

Meanwhile, the portion of the law that's now supposed to be in effect is barely being enforced. That's because the agencies charged with enforcing it, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, don't have enough money or staff to do the job. Congress hasn't seen fit to appropriate these necessities.

Several of these agencies are still lacking directors or commissioners. Senate Republicans have refused to confirm anyone. They wouldn't even consider Elizabeth Warren to run the new consumer bureau.

Many of same business leaders who blame the sluggish economy on regulatory uncertainty are complicit in all this. A senior vice president of the Chamber of Commerce told the New York Times that "uncertainty among companies about the rules of the road is keeping a lot of capital on the sidelines." The Chamber has been among the groups responsible for keeping Dodd Frank at bay.

But it's the biggest Wall Street banks – the ones that got us into this mess in the first place, and got bailed out by the public – that have taken the lead in killing off Dodd-Frank. They can afford the hit job.

At the same time, their executives – enjoying pay and bonuses as large as in the boom days of the housing bubble – are busily bankrolling both political parties, although Republicans are favored in this election cycle. A significant portion of Mitt Romney's sizable war chest has come from the Street. President Obama is no slouch when it comes to pulling at the Street's purse strings.

Bankers try to justify their shameful murder of Dodd-Frank by saying tightened regulatory standards will put them at a disadvantage relative to their overseas competitors. JP Morgan's Jamie Dimon had the nerve to publicly accost Ben Bernanke recently, complaining that the law's implementation would harm the Street's competitiveness.

The argument is pure claptrap. In the wake of global finance's near meltdown, Europe has been more aggressive than the United States in clamping down on banks headquartered there. Britain is requiring its banks to have higher capital reserves than are so far contemplated in the United States. In fact, senior Wall Street executives have warned European leaders their tighter bank regulations will cause Wall Street to move more of its business out of Europe.

Wall Street is global because capital is global. JP Morgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Bank of America, and Morgan Stanley are doing business in every corner of the world. Goldman even advised Greece on how to hide its growing indebtedness, before the rest of the world got wind, through a derivatives deal that circumvented Europe's deficit rules.

The real reason Wall Street has spent the last year bludgeoning Dodd-Frank into meaninglessness is the vast sums of money it can make if Dodd-Frank is out of the way. If you took the greed out of Wall Street all you'd have left is pavement.

Wall Street is the richest and most powerful industry in America with the closest ties to the federal government – routinely supplying Treasury secretaries and economic advisors who share its world view and its financial interests, and routinely bankrolling congressional kingpins.

How else can you explain why the Street was bailed out with no strings attached? Or why no criminal charges from being brought against any major Wall Street figure – despite the effluvium of frauds, deceptions, malfeasance and nonfeasance in the years leading up to the crash and subsequent bailout? Or why Dodd-Frank has been eviscerated?

As a result of consolidations brought on by the bailout, the biggest banks are bigger and have more clout than ever. They and their clients know with certainty they will be bailed out if they get into trouble, which gives them a financial advantage over smaller competitors whose capital doesn't come with such a guarantee. So they're becoming even more powerful.

Face it: The only answer is to break up the giant banks. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was designed not only to improve economic efficiency by reducing the market power of economic giants like the railroads and oil companies but also to prevent companies from becoming so large that their political power would undermine democracy.

The sad lesson of Dodd-Frank is Wall Street is too powerful to allow effective regulation of it. We should have learned that lesson in 2008 as the Street brought the rest of the economy – and much of the world – to its knees. Now we're still on our knees but the Street is back on top. Its leviathans do not generate benefits to society proportional to their size and influence. To the contrary, they represent a clear and present danger to our economy and our democracy.

They should be broken up, and their size must be capped. Congress won't do it, obviously. So we'll need to rely on the nation's two antitrust agencies — the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department. The trust-busters are now investigating Google. They should be turning their sights onto JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, and Goldman Sachs instead.

July 17, 2011

The Dangerous Hi-Jinks of the GOP's Juveniles

I've spent enough of my life in Washington to take its theatrics with as much seriousness as a Seinfeld episode. A large portion of what passes for policy debate isn't at all — it's play-acting for various constituencies. The actors know they're acting, as do their protagonists on the other side who are busily putting on their own plays for their own audiences.

Typically, though, back stage is different. When the costumes and grease paint come off, compromises are made, deals put together, legislation hammered out. Then at show time the players announce the results – spinning them to make it seem they've kept to their parts.

At least that's the standard playbook.

But this time there's no back stage. The kids in the GOP have trashed it. The GOP's experienced actors – House Speaker John Boehner and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McDonnell – have been upstaged by juveniles like Eric Cantor and Michele Bachmann, who don't know the difference between playacting and governing. They're in league with tea party fanatics who hate government so much they're willing to destroy the full faith and credit of the United States. Washington has gone from theater to reality TV – a game of hi-jinks chicken that could end in a crash.

So now the GOP's experienced actors are trying to retake the stage. They've set a vote Tuesday for a so-called "cut, cap, and balance" plan – featuring an immediate $100 billion-plus cut from next year's budget and a constitutional amendment requiring a balanced budget.

The plan would be a disaster for the nation, of course – a cut of that magnitude when the economy is still struggling to get out of recession would plunge it back in, and a balanced-budget amendment would make it impossible to counteract future recessions with extra spending and tax cuts.

But, hey, it's all for show. The GOP's adults know the President would veto their cuts and they couldn't possibly muster the two-thirds of the Senate and House needed to override the veto. Nor, obviously, do they have the two-thirds necessary to pass a constitutional amendment.

The point is to give the kids more votes they can wave in the direction of their tea party constituents. It's hoped that the "cut, cap, and balance" plan — along with Mitch McConnell's proposed Republican vote disapproving the President's move to raise the debt ceiling (which the President will then veto) — will be enough to get the juveniles to raise the debt ceiling before the August 2 deadline.

"The cut, cap and balance plan that the House will vote on next week is a solid plan for moving forward," John Boehner told reporters Friday. Translated: I hope this will be enough playacting to get their votes on the debt ceiling.

But even if it's enough, the bigger problem remains: There's still no back stage where the real work of governing this country can occur. At best, the vote to raise the debt ceiling kicks the can down the road only until the end of 2012. By then, if we don't elect adults, the kids will be in charge.

July 15, 2011

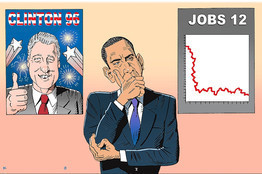

Can Obama Pull a Clinton on the GOP?

After a bruising midterm election, the president moves to the political center. He distances himself from his Democratic base. He calls for cuts in Social Security and signs historic legislation ending a major entitlement program. He agrees to balance the budget with major cuts in domestic discretionary spending. He has a showdown with Republicans who threaten to bring government to its knees if their budget demands aren't met. He wins the showdown, successfully painting them as radicals. He goes on to win re-election.

Barack Obama in 2012? Maybe. But the president who actually did it was Bill Clinton. (The program he ended was Title IV of the Social Security Act, Aid to Families with Dependent Children.)

It's no accident that President Obama appears to be following the Clinton script. After all, it worked. Despite a 1994 midterm election that delivered Congress to the GOP and was widely seen as a repudiation of his presidency, President Clinton went on to win re-election. And many of Mr. Obama's top aides—including Chief of Staff Bill Daley, National Economic Council head Gene Sperling and Pentagon chief Leon Panetta—are Clinton veterans who know the 1995-96 story line by heart.

Republicans have obligingly been playing their parts this time. In the fall of 1995, Speaker Newt Gingrich was the firebrand, making budget demands that the public interpreted as causing two government shutdowns—while President Clinton appeared to be the great compromiser. This time it's House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and his Republican allies who appear unwilling to bend and risk defaulting on the nation's bills—while President Obama offers to cut Social Security and reduce $3 of spending for every dollar of tax increase.

And with Moody's threatening to downgrade the nation's debt if the debt limit isn't raised soon, Republicans appear all the more radical.

So will Barack Obama pull a Bill Clinton? His real problem is one Mr. Clinton didn't have to contend with: a continuing terrible economy. The recession in 1991-92 was relatively mild, and by the spring of 1995, the economy was averaging 200,000 new jobs per month. By early 1996, it was roaring—with 434,000 new jobs added in February alone.

View Full Image

Martin Kozlowski

Martin Kozlowski

I remember suggesting to Mr. Clinton's then-political adviser, Dick Morris, that the president come up with some new policy ideas for the election. Mr. Morris wasn't interested. The election will be about the economy—nothing more, nothing less, he said. He knew voters didn't care much about policy. They cared about jobs.

President Obama isn't as fortunate. The economy remains hampered by the Great Recession, brought on not by overshooting by the Federal Reserve but by the bursting of a giant housing bubble. As such, the downturn has proven resistant to reversal by low interest rates. The Fed has kept interest rates near zero for more than two years, opened the spigots of its discount window, and undertaken two rounds of quantitative easing—all with little to show for it.

Some in the White House and on Wall Street assume the anemic recovery will turn stronger in the second half of the year, emerging full strength in 2012. They blame the anemia on disruptions in Japanese supply chains, bad weather, high oil prices, European debt crises, and whatever else they can come up with. These factors have contributed, but they're not the big story.

When the Great Recession wiped out $7.8 trillion of home values, it crushed the nest eggs and eliminated the collateral of America's middle class. As a result, consumer spending has been decimated. Households have been forced to reduce their debt to 115% of disposable personal income from 130% in 2007, and there's more to come. Household debt averaged 75% of personal income between 1975 and 2000.

We're in a vicious cycle in which job and wage losses further reduce Americans' willingness to spend, which further slows the economy. Job growth has effectively stopped. The fraction of the population now working (58.2%) is near a 25-year low—lower than it was when recession officially ended in June 2009.

Wage growth has stopped as well. Average real hourly earnings for all employees declined by 1.1% between June 2009, when the recovery began, and May 2011. For the first time since World War II, there has been a decline in aggregate wages and salaries over seven quarters of post-recession recovery.

This is not Bill Clinton's economy. So many jobs have been lost since Mr. Obama was elected that, even if job growth were to match the extraordinary pace of the late 1990s—averaging 300,000 to 350,000 per month—the unemployment rate wouldn't fall below 6% until 2016. That pace of job growth is unlikely, to say the least. If Republicans manage to cut federal spending significantly between now and Election Day, while state outlays continue to shrink, the certain result is continued high unemployment and anemic growth.

So Mr. Obama's challenge in 2012 has nothing to do with Mr. Clinton's in 1996. Most Americans care far more about jobs and wages than they do about budget deficits and debt ceilings. Even if Mr. Obama is seen to win the contest over raising the debt limit and succeeds in painting Republicans as radicals, he risks losing the upcoming election unless he directly addresses the horrendous employment problem.

How can he do this while continuing to appear more reasonable than Republicans on the deficit? By coming up with a bold jobs plan that would increase outlays over the next year or two but would credibly begin a long-term plan to shrink the budget. To the extent the jobs plan spurs growth, the long-term ratio of debt to GDP will improve.

Elements of the plan might include putting more money into peoples' pockets by exempting the first $20,000 of income from payroll taxes for the next year, recreating a Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps to employ the long-term jobless, creating an infrastructure bank to finance improvements to roads and bridges, enacting partial unemployment benefits for those who have been laid off from part-time jobs, and giving employers tax credits for net new hires.

The fight over the debt ceiling will be over very soon. Most Washington hands know it will be raised. Political tacticians know President Obama will likely appear to win the battle, and his apparent move to the center will make Republicans look like radicals. But the Clinton script will take the president only so far. If he wants a second term, he'll have to come out swinging on jobs.

[I wrote this for today's Wall Street Journal]

The Rise of the Wrecking-Ball Right

Recently I debated a conservative Republican who insisted the best way to revive the American economy was to shrink the size of government. When I asked him to explain his logic he said, simply, "government is the source of all our problems." When I noted government spending had brought the economy out of the previous eight economic downturns, including the Great Depression, he disagreed. "The Depression ended because of World War Two," he pronounced, as if government had played no part in it.

A few days later I was confronted by another conservative Republican who blamed the nation's high unemployment rate on the availability of unemployment benefits. "If you pay someone not to work, they won't," he said. When I pointed out unemployment benefits couldn't possibly be the cause of joblessness because there are now about five job seekers for every job opening, he scoffed. "Government always makes things worse."

Government-haters seem to be everywhere.

Congressional Republicans, now led by House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, hate government so much they're ready to sacrifice the full faith and credit of the United States in order to shrink it.

Taming the deficit isn't their aim. They rejected Obama's offer to cut $3 trillion of spending over the decade – including major reductions in entitlement programs – because his plan would also entail $1 trillion of tax increases. Their ultimate goal, in the words of their guru Grover Norquist, is to take government down to "the size where we can drown it in the bathtub."

Where did this wrecking crew come from? And why do so many Americans seem to support them? To answer "the tea party" begs the question because the tea party itself is a product of this raging

Credit the economic fears and insecurities now felt by a broad swathe of the public who want to find a villain for what they're going through. Wall Street is too abstract and the financial games that brought on the Great Recession almost impossible for most Americans to grasp. But the government bailout of the Street was a specific act almost everyone could instinctively understand – and to most Americans it seemed perversely wrong.

It's no coincidence that the emergence of the tea party coincided with the Wall Street bailout. An acquaintance who has embraced the tea party explained to me she hates government "because it's always captured by the powerful, who take our taxes and eat our lunch."

At the same time most of what government does that helps average people is now so deeply woven into the thread of daily life that it's no longer recognizable as government. Think of the indignant voters who showed up at congressional town meetings to protest Obama's health care bill shouting "don't take away my Medicare!"

A recent paper by Cornell political scientist Suzanne Mettler surveyed how many recipients of government benefits don't really believe they have received any benefits. She found that over 44 percent of Social Security recipients say they "have not used a government social program." More than half of families receiving government-backed student loans said the same thing, as did 60 percent of those who get the home mortgage interest deduction, 43 percent of unemployment insurance beneficiaries, and almost 30 percent of recipients of Social Security Disability.

Add in the relentlessly snide government-hating and baiting of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh and his imitators on rage radio; include more than thirty years of Ronald Reagan's repeated refrain that government is the problem; pile on hundreds of millions of dollars from the likes of oil tycoons Charles and David Koch intent on convincing the public that government is evil, and you have all the ingredients for the emergence of a wrecking-ball right that's intent on destroying government as we know it.

The final critical ingredient has been the abject failure of the Democratic Party – from the President on down – to make the case for why government is necessary.

One would have thought the last few years of mine disasters, exploding oil rigs, nuclear meltdowns, malfeasance on Wall Street, wildly-escalating costs of health insurance, rip-roaring CEO pay, and mass layoffs would have offered a singular opportunity to explain why the nation's collective well-being requires a strong and effective government representing the interests of average people.

Yet the case has not been made. Perhaps that's because, even under the Democrats, the interests of average people have not been sufficiently attended to.

July 13, 2011

Why Mitch McConnell Will Win the Day

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell's compromise on the debt ceiling is a win for the President disguised as a win for Republicans. But it really just kicks the can down the road past the 2012 election – which is what almost every sane politician in Washington wants to happen in any event.

McConnell's plan would allow the President to raise the debt limit. Congressional Republicans could then vote against the action with resolutions of disapproval. But these resolutions would surely be vetoed by the President. And such a veto, like all vetoes, could only be overridden by two-thirds majorities in both the House and Senate – which couldn't possibly happen with the Democrats in the majority in the Senate and having enough votes in the House to block an override.

Get it? The compromise allows Republicans to vote against raising the debt limit without bearing the horrendous consequences of a government default.

No budget cuts. No tax increases. No clear plan for deficit reduction. Nada. The entire, huge, mind-boggling, wildly partisan, intensely ideological, grandly theatrical, game of chicken miraculously vanishes.

Until the 2012 election, that is.

McConnell, like most other Republican leaders, has all along seen the battle over raising the debt ceiling as part of a master plan to unseat Obama. Remember, it was McConnell who openly admitted the GOP's "top goal is to defeat President Obama in 2012" – a brazen and bizarre statement in the face of the worst economic crisis in seventy years.

The GOP will weave Obama's decision to raise the debt ceiling into the 2012 presidential campaign –- as well as Senate and House races — so 2012 becomes what they hope will be a referendum on Obama's "big government."

McConnell's compromise will win the day. Expect much grousing from the GOP, especially those who feel they need to posture for the tea party. But McConnell – or something very similar – is the only way out. Obama can't agree to a budget plan lacking tax increases, especially on the wealthy. Republicans can't agree to one including them. In Washington, when an immovable object meets an irresistible force, something's got to give. A compromise that allows both sides to save face is the easiest give of all.

Moreover, as the August 2 deadline approaches, big business and Wall Street (who hold the purse strings for the GOP) are sending Republicans a clear signal: Raise the debt ceiling or capital markets will start getting nervous. And if they get nervous and interest rates start to rise, you guys will be blamed.

Washington insiders will consider the McConnell compromise a win for Obama. But the rest of the country hasn't been paying much attention and won't consider it much of a win for either side. Their attention is riveted to the economy, particularly jobs and wages. If those don't improve, Obama will be a one-term president regardless of how the GOP wants to paint him.

July 12, 2011

The President's Jobs Plan (Not)

What did the President do in response to last week's horrendous job report — unemployment rising to 9.2 percent in June, with only 18,000 new jobs (125,000 are needed each month just to keep up with the growth in the potential labor force)?

He said the economy continues to be in a deep hole, and he urged Congress to extend the temporary reduction in the employee part of the payroll tax, approve pending free-trade agreements, and pass a measure to streamline patent procedures.

To call this inadequate would be a gross understatement.

Here's what the President should have said:

This job recession shows no sign of ending. It can no longer be blamed on supply-side disruptions from Japan, Europe's debt crisis, high oil prices, or bad weather.

We're in a vicious cycle where consumers won't buy more because they're scared of losing their jobs and their pay is dropping. And businesses won't hire because they don't have enough customers.

Here in Washington, we've been wasting time in a game of chicken over raising the debt ceiling. Republicans want you to believe the deficit is responsible for the bad economy. The truth is that when the private sector cannot and will not spend enough to get the economy going, the public sector must step into the breach. Cutting the deficit now would only create more joblessness.

My first priority is to get Americans back to work. I'm proposing a jobs plan that will do that.

First, we'll exempt the first $20,000 of income from payroll taxes for the next two years. This will put cash directly into American's pockets and boost consumer spending. We'll make up the revenue shortfall by applying Social Security taxes to incomes over $500,000.

Second, we'll recreate the WPA and Civilian Conservation Corps — two of the most successful job innovations of the New Deal – and put people back to work directly. The long-term unemployed will help rebuild our roads and bridges, ports and levees, and provide needed services in our schools and hospitals. Young people who can't find jobs will reclaim and improve our national parklands, restore urban parks and public spaces, recycle products and materials, and insulate public buildings and homes.

Third, we'll enlarge the Earned Income Tax Credit so lower-income Americans have more purchasing power.

Fourth, we'll lend money to cash-strapped state and local governments so they can rehire teachers, fire fighters, police officers, and others who provide needed public services. This isn't a bailout. When the economy improves, scheduled federal outlays to these states and locales will drop by an amount necessary to recover the loans.

Fifth, we'll amend the bankruptcy laws so struggling homeowners can declare bankruptcy on their primary residence. This will give them more bargaining leverage with their lenders to reorganize their mortgage loans. Why should the owners of commercial property and second homes be allowed to include these assets in bankruptcy but not regular home owners?

Sixth, we'll extend unemployment benefits to millions of Americans who have lost part-time jobs. They'll get partial benefits proportional to the time they put in on the job.

Yes, most of these measures will require more public spending in the short term. But unless we get this economy moving now, the long-term deficit problem will only grow worse.

Some in Congress will fight against this jobs plan on ideological grounds. They don't like the idea that government exists to help Americans who need it. And they don't believe we all benefit when jobs are more plentiful and the economy is growing again.

I am eager to take them on. Average Americans are hurting, and their pain is not going away.

We bailed out Wall Street so that the financial system would not crash. We stimulated the economy so that businesses would not tank. Now we must help ordinary people on the Main Streets of America — for their own sakes, and also so that the real economy can fully mend.

My most important goal is restoring jobs and wages. Those who oppose me must explain why doing nothing is preferable.

Robert B. Reich's Blog

- Robert B. Reich's profile

- 1243 followers