R.J. Wheaton's Blog, page 3

September 28, 2011

Back from the Printers

[image error]

It's a "chunky monster" indeed. Packed to the seams with everything you need to know about mid-90s British downtempo music, massive basslines in golden age hip-hop, the relationship between funky jazz fusion and World War II bomber aircraft, and hundreds of other topics central to the proper functioning of your life.

I'm thrilled that it's publishing next to Aaron Cohen's book on Aretha Franklin's Amazing Grace. That'll be a must-read.

August 23, 2011

Gravelly Full-Hearted Thunderous Power Ballad Playlist

Circumstances:

Long proof-reading session for forthcoming Dummy book.

Recent exposure to Harry/Hermione dancing scene.

John Carter of Mars trailer.

Result:

Playlist of thunderous gravelly full-hearted songs that will rattle your bones.

"O Children" -- Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. From The Lyre of Orpheus. Nobody does violence and grace as artfully as Nick Cave. Elegiac. Thrilling. The song seems to be contingent (what are those strange reversed sounds at the back? is the song falling apart?) even as it gathers itself into a hymn. One of the best moments of the Harry Potter movies -- intimate and expansive at the same time. How is it done.

"My Body is a Cage" -- Peter Gabriel. If the John Carter of Mars movie is good (it's Andrew Stanton, people) it'll still have to go some distance to outpace this cover of an Arcade Fire song which builds to a thunderous climax. Again and again. The god of war.

"O Mary Don't You Weep" -- Bruce. From We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. First heard this over the closing credits somewhere in the third season of Deadwood, this rambunctious spiritual somehow serving as a response to David Milch's excoriating portrait of capitalist rapacity in George Hearst. It's all muscle and throat.

[image error]Do not mess with George Hearst

"Dolphins" -- Beth Orton featuring Terry Callier. Why don't more people know this song? From an EP that came out in 1997 and was one of the best things she's ever done. It's a Tim Buckley song. Terry Callier's voice is like an ocean liner.

"Everybody's Gotta Learn Sometime" -- Beck. From Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

"Just Like a Woman" and "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" -- Joe Cocker. Both from 1969's With a Little Help From My Friends. One of the warmest, most soulful albums ever recorded. Up there with Lewis Taylor's debut and Dusty in Memphis and McKay as one of the great, great British R&B albums.

"Loved Boy" featuring Lou Rawls, and "The Little Children" featuring Ras Kass, by David Axelrod, from 2001's Mo'Wax album David Axelrod. I should write something longer about this album, it's been haunting my collection for years. One of those great projects that Mo'Wax kicked out. I still remember hearing "The Little Children" in a bar in Oxford on Little Clarendon Street in 2001. Who the hell would play this in a bar? It's like a symphony with a brawl in the middle of it. In "Loved Boy" Rawls is all stately and measured above drunken trumpets.

"This Strange Affair" -- The Peddlers, from 1972's Suite London. I write about this album in the book, a distinct influence on Dummy. I can't improve much on what Tim Saul told me about it: "a very strange kind of mixture of almost working man's club crooning over really interesting arrangements with the London Philharmonic."

Some Tom Waits, obviously. I can't decide. "Way Down in the Hole," but it's a bit over-familiar because of The Wire. Maybe "Cold Cold Ground": very accessible but still somehow unstable. Or "Clap Hands": an arrangement that seems to float a few feet off the ground and drag you through the song even while Waits follows just behind your ear. Bizarre. I must pick up David Smay's book again.[image error]

Buck 65. Where to start. "Roses and Blue Jays"; absolutely gorgeous songcraft. Or "Cries a Girl." I've written about these songs before and I'm still right:

Terfry's various story-telling influences—including Waits, Johnny Cash, Woody Guthrie, Jack Kerouac—have by now been so thoroughly absorbed into a developed and individual style that it is next to impossible to pick them out... There's a perfect confidence to his writing, a confidence that allows a song as personal as "Roses and Bluejays"—about his relationship with his father since his mother's death—to be conducted entirely at the level of surface observations. The details themselves, and their juxtaposition, perfectly conjure a sense of drift and directionlessness, and, somehow, a deep-rooted belonging. The image of his father clearing snow with a flamethrower encapsulates a moment of rage, loneliness, of silent futility.

A few of these would fit on a Suttree playlist. To follow.

Couldn't find YouTube links to the Axelrod or Peddlers -- apologies. Trust me, they're good. Please buy the music if you like it. Musicians need to eat too.

August 12, 2011

Review of Earthling's Insomniac's Ball

I had the pleasure and privilege of interviewing Tim Saul for the Dummy book. Saul is a long-time collaborator of Portishead producer Geoff Barrow (with whom he co-produced 2003's outstanding McKay) and he was involved in pre-production sessions for Dummy. His insights into the production of that album were invaluable.

Saul is also, with rapper Mau, half of Earthling, whose 1995 Radar remains representative of the best of the downtempo genre before if became stylistically flattened by its own commercial viability. Seven years after the release of their second album, their third -- Insomniac's Ball -- is out and available via Bandcamp. My review is up on PopMatters this morning:

There are some stunning moments of beatcraft. The opening of "Bobby X" is as meticulous a piece of loop production as you might hear this side of hip-hop's Golden Age. It opens with a shuddering, withdrawing, pugnacious sample: a back-drawn snare like a rasp of drawn breath, piano from the bottom and top of the register clasping the song in iron gloves. Shards of sound seem to slide past one another, assembling a beat out of near-collisions. Yet somehow Mau's boastful lyrics—"gonna let the whole world know I'm here"—are tempered by his thrillingly idiosyncratic delivery. They are less a compilation of braggadocio and instead—"so don't ask me about philosophies of Archimedes, my education was beat-street and graffiti"—an eminently quotable coalition of nimble charm and cheeky grace.

This was always the magic in Saul and Mau's collaboration. Much like Barrow and Beth Gibbons in Portishead, or Tricky and Martina Topley-Bird, the finest moments in downtempo were not the smooth congregation of like minds, but a rich and intoxicating marriage of contrasts.

Be sure to check out at least "Bobby X" and the gorgeous "Fly Away".

July 19, 2011

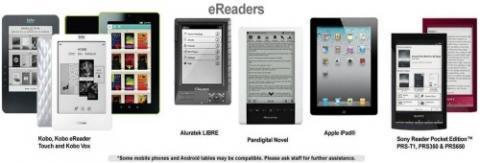

Not Books, but Doors: Why eReading is a More Immersive Experience

[NOTE: this post originally appeared on Datachondria, a blog dedicated to technology, data, and modern life.]

I've been reading electronically -- phone, desktop (I know), Kobo, Kobo Touch -- for perhaps two years now, and I've come to the following conclusion as my reading habits have changed.

Electronic reading does a better job of engaging the reader's imagination than print books do.

It's also, of course, a more physically pleasurable experience:

LighterEasier to operate (I'm talking about turning pages, and believe me no one is a better one-handed print page-turner than I am)Less likely to wake you up when you drop it on your face when falling asleep readingNot going to bedazzle you with glare when reading in bright sunlight (seriously, reading a good e-ink display beside a pool is a world-class experience)But all of those are ultimately secondary. What eReading is really, really good at is letting you be a creative reader. Reading is the act of imaginatively interpreting -- reconstructing -- the work of an another person's imagination. That's subject to two sets of constraints: the range and ability of the author to express their imagination; and the range and ability of the reader to interpret it, which is to say, to creatively reimagine it on their own terms. Technology is not a neutral factor in that relationship. And electronic readers do a better job of relaxing the second set of those constraints.

Here's what I've noticed about my reading experience over the last couple dozen months.

1. I'm reading more.

Having a vast array of content to choose from means less reading time lost because I'm not quite in the mood for the book that I happened to bring with me. And that's exactly the point: I can read according to my mood -- not have to remember to bring a book strong enough to change my mood. Every time.

So, I'm better read -- but also have the ability to start reading something on a spur-of-the-moment suggestion. If I'm at a party and someone says, look, you have to read The Poisonwood Bible, I can start reading it on the bus on the way home instead of the Pretty Little Liars #9 that I was reading on the way there. This possibility, alone, makes me feel better read, because it's always within reach. The horizons of my imagination feel broader. (It doesn't hurt that the prices are usually lower.)

2. I'm far less tolerant of poorly written non-fiction.

Perhaps that's not quite fair: I'm far less tolerant of non-fiction that is written without a distinctive voice, or at the very least some concession to narrative structure. For all the improvements of scrolling and progress indicators, it remains much easier to skim a print book than an eBook. Which means I have to page through the eBook... and if it's boring I'd just as soon move onto something else. But on an eReader, the abandoned books aren't staring me in the face in some strange transfiguration of guilt and anxiety. In short: I'm in control of the reading experience -- unless the author is really, really good; unless they are actively contributing towards the mutual creative act.

Hanna from Pretty Little Liars

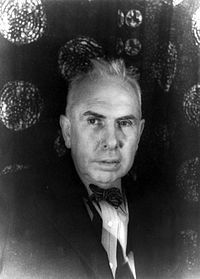

Theodore Dreiser

Perhaps we do lose something in that. "Great books don't promise to hold your attention," I remember an English professor once telling a class utterly bored by one of the masters of American literature (probably Dreiser), "but they do promise to reward it." I suspect that, in a future when electronic reading is the dominant manner of reading, authors who can't write well will not be able to release ideas slowly. (And if we don't read Dreiser, we'll all miss out on some of the more amusing fender-benders of American prose.)

On the other hand:

3. I can concentrate better

Somehow the flexibility of the form -- yes, the font size, the typeface selection -- means that I can get better terms in the reading relationship. I can take my glasses off but still read without having to hold the device a couple of inches from my face. It's less about the conditions that I must arrange in order to read, and more about how I can manipulate the content to suit me.

4. I don't feel like I'm carrying a book around

Because I'm not. I'm not carrying hundreds of books either. At a certain point, having more books than I could list made my device something less like a book, or a compendium, than a portal: a door. That was one of the thrilling discoveries of the first Kobo reader: it came pre-loaded with a hundred free books, which made it clear that this technology was not simply a more efficient distribution mechanism, but a gateway to limitless content. Wi-fi devices have absolutely helped with that too -- but they have kept the connection to the wider Internet obscure enough that I'm not prone to jump on Twitter or the web. Reading remains immersive, yet feels connected.

5. The books I have read feel closer to one another

And that sense of connection, crucially, extends to the books I have already read. Somehow the ability to have the complete works (well, not quite yet) of Faulkner, Didion, Murakami, and John McPhee in my bag, at all times, gives me a more holistic sense of my reading life than having them marooned, out of reach, on a bookshelf, where their valences are confined to the sequence in which I happen to have them shelved. The connections between these books are multiple and they continually expand as I -- by the sheer act of reading -- add to their company. Virtual shelves aren't the same as real shelves, and the books I have on my Kobo live in the same kind of unregulated relationships to one another than they do in my imagination.

John McPhee: The Non-Portable Version

By amalgamating possibility, your aggregate reading experience, the range of your reading and your interests, electronic readers offer a sort of physical external representation of your imagination. They are a sort of auxiliary imagination. My Kobo Touch, after only a few weeks, houses hundreds of books and hundreds of annotations and highlights; it has measured and marked my progress through novels and essays (and, yes, I earned the insomniac badges along the way). It hasn't just been a device: it's been a companion.

Reading merges the content of the page with everything else you have ever read, through the filter of your imagination. It is a cumulative, messy process: it disintegrates the boundaries between ideas, times, places, people, events. It is a process of unseaming the constraints of reality; of unspooling it into the collective and personal reaches of the imagination. And the eReading device is by definition a much better metaphor for that process than physical books. Ideas collide, aggregate, pile into one another. They are sunk within you. They do not remain distinct.

Perhaps this is how the listeners to epic poetry once felt, as the stories that are now The Iliad and The Odyssey were released into the collective ether. Perhaps physical books were a transitional media.

So that's where I'm at. Admittedly other things have conspired to bring me there. I'm not at a point in my life where I still strongly feel the need to display my books around me as an expression of my refinement and taste, and in any event it's rare that a book changes me in the way of a Slouching Towards Bethlehem or Light in August: my imagination is more robust than it was when I was 21, and I've already discovered many of the books most likely to change me. What's more, the limitations of urban living have somewhat necessarily curtailed my ability to endlessly collect books.

But still: I've fallen out of love with shelves of trade paperbacks, and back in love with something that feels closer to the experience of reading itself.

Reading a physical book still retains its pleasures: there is absolutely something thrilling about a gorgeous hardcover, something that feels like a communion close to the author's intent. But that's exactly the point: physical books make you read on the author's terms; reading electronically takes place more on the reader's terms. I think that's a good thing. It makes reading more personal, more democratic, more controversial.

But it's a huge change -- and it could be a generation before authors catch up to it.

May 8, 2011

Jay Hodgson's Understanding Records

One of several great discoveries in the course of writing the 33 1/3 book on Portishead's Dummy was Jay Hodgson's wonderful Understanding Records: A Field Guide to Recording Practice. Hodgson has a talent for demystifying modern recorded sound, without ever detracting from the thrilling qualities of the music. As an example, as part of a discussion of distortion:

Reinforcement distortion does not necessarily require signal processing. Jimmy Miller, for instance, often reinforced Mick Jagger's vocals on the more energetic numbers he produced for the Rolling Stones by having Jagger or Keith Richards shout a second take, which he then buried deep in the mix. "Sympathy For The Devil," for instance, features a shouted double in the right channel throughout, though the track is faded so that it only sporadically breaches the threshold of audibility; "Street Fighting Man" offers another obvious example. "Let It Bleed" provides another example of shouted (manual) reinforcement distortion, though Miller buried the shouted reinforcement track so far back in the mix that it takes headphones and an entirely unhealthy playback volume to clearly hear. By the time Miller produced the shambolic Exile On Main Street, however, he had dispensed with such preciousness altogether: the producer regularly pumps Jagger's and Richards' shouted reinforcement tracks to an equal level with the lead-vocals on the album.

[image error]Hodgson is every bit as insightful and enthusiastic in person as he is in text. He was incredibly generous with his time and, over the course of a couple of conversations and email exchanges, helped me hear Dummy from the perspective of an audio professional, which was invaluable as I prepared to speak to Dummy and Portishead sound engineer Dave McDonald and mastering engineer Miles Showell. There are passages of my book -- particularly around the recording techniques for the album's vocals and its drum sounds -- that are informed by his insights and coloured by the questions that I only knew to ask after he had helped trained my ears.

While certainly intended for a professional audience, Understanding Records is a great read for the music enthusiast: Hodgson's writing is clear and alight with anecdotes and examples that illuminate music that you may only think you know. I'll never hear recorded music quite the same way again.

January 1, 2010

October 31, 2009

Introducing Portishead's Dummy, a 33 1/3 Book

Portishead's 1994 album Dummy reassembles itself with every listen and with each listener. It becomes, cumulatively and collectively, a sequence of perfect meditations on loneliness and solitude; it carries promises of the narcotizing power of love; it serenades the anonymous consolations of the night; it rhapsodizes the unmooring influence upon the soul of unrequited and obsessive desire.

Dummy is irresistibly intimate, stylistically eclectic. A mixture of influences drawn from hip-hop, rock, jazz, folk, soul, funk, blues, and elsewhere, the album is a sparsely woven tapestry of sounds striped from their origins -- shards of lyrics, samples, gestures, surfaces, textures. It is held together only by inertia and by the force of the memories, impressions, and perceptions it provokes in the listener -- only to fall away undone and unresolved into darkness.

An entry in Continuum's 33 1/3 series, Portishead's Dummy will be published in 2011.

I'm looking for stories about this music. What were you doing when you first heard it? How did it change your life? How has listening to it changed the way that you thought about what music could do?

We live in a world where music is infinitely distributable, ubiquitous in its presence, contextless in conception and reception. Music lives and dies in a place of continuous reinterpretation by its listeners.

What does Dummy mean to you?

Email: dummy333@rjwheaton.com

Twitter: @dummy333

Facebook: Dummy 33 1/3 page

Or comment below.