Gordon Grice's Blog, page 93

June 20, 2011

Death Stories: Slice, Part 5

Go to the beginning of this story

If you wanted to be resurrected in the end time, Church dogma used to say, you need a complete body. Whatever might be found inside was "God's province." Doctors concentrated instead on herbal medicine and other strategies that didn't require much knowledge of anatomy. Barbers handled the lancing of boils and the bleeding with leeches. Medical schools taught anatomy as a theoretical subject, if at all.

Then, in the 13th century, legal systems in Europe began to sanction autopsies to determine causes of death. Some universities began to include anatomical demonstrations using the corpses of criminals. Typically, the authorities preferred to give over foreign criminals, since their families would not be around to protest. Jews and other marginalized people were also likely candidates. Complex regulations surrounded these demonstrations; sometimes even the number of masses to be said for the deceased was mandated by law. In a room stocked with rosewater and incense, a professor might read from a text while a junior academic pointed to the relevant body parts with a wand. Neither handled or cut the cadaver; that was still the job of a barber—a grotesque rendition of "Those who can't do, teach." At some universities, only medical students and doctors were allowed in; elsewhere, dissections were open to anyone who could pay the admission fee. Spectators might bring spices to cover the smell; or they might buy oranges from the vendors.

In the Renaissance, the Church, which had previously leaned toward the position that dissection ruined one's chances of being bodily resurrected on judgment day, shifted toward the idea that dissection could only enhance human appreciation of God's handiwork. This new idea infected the arts. Painters flayed cadavers to study their muscles and thereby depict the exterior of the body with greater verisimilitude. Leonardo da Vinci began his studies of anatomy by observing such flayings, but eventually he delved deeper, exploring beyond painterly questions. He boasted that he had whittled away "more than ten" cadavers just to diagram the circulatory system--no single body lasted long enough. He claimed that his drawings, which included such innovations as the cross-section, were more useful for learning the body than watching a dissection oneself, because a dissection destroys some structures in probing for others. Having investigated the digestive system, he concluded that "men and animals are only a track, a conduit for food, a burial for other birds, an inn for the dead."

Great confusion results from the combination of tissues, with veins, arteries, nerves, sinews, muscles, bones, and blood which, of itself, tinges every part the same colour. And the veins, which discharge this blood, are not discerned by reason of their smallness. Moreover integrity of the tissues, in the process of the investigating the parts within them, is inevitably destroyed, and their transparent substance being tinged with blood does not allow you to recognise the parts covered by them, from the similarity of their blood-stained hue; and you cannot know everything of the one without confusing and destroying the other.

-- Leonardo da Vinci

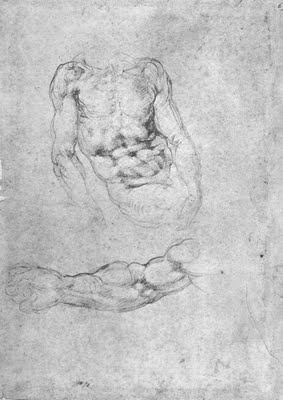

For the anatomical knowledge of his rival Michaelangelo, Leonardo had only scorn. He claimed Michaelangelo's figures were muscled like "bags of nuts." Nonetheless, Michaelangelo himself performed dissections, and a leading anatomist of the day recruited him to illustrate a text. That assignment didn't work out; nor did his ambition to illustrate a treatise on proportion by Durer. But he did help to found a school for artists where anatomy was a required subject.

Michaelangelo: Bags of Nuts

Michaelangelo: Bags of NutsThe most influential anatomist of the Renaissance was Andreas Vesalius. His extraordinary texts are filled with innovative cross-references and illustrations—some possibly provided by Titian—but his real accomplishment was to expose the weaknesses in works by Galen and others by testing the received lore against actual bodies.

I am thinking of a great fellow, who was about as old as I am three hundred years ago, and had already begun a new era in anatomy. His name was Vesalius. And the only way he could get to know anatomy as he did, was by going to snatch bodies at night, from graveyards and places of execution. He could only get a complete skeleton by snatching the whitened bones of a criminal from the gallows, and burying them, and fetching them away by bits secretly, in the dead of night. Some of the greatest doctors living were fierce upon Vesalius because they had believed in Galen, and he showed that Galen was wrong. They called him a liar and a poisonous monster. But the facts of the human frame were on his side; and so he got the better of them. He had a good deal of fighting to the last. And they did exasperate him enough at one time to make him burn a good deal of his work. Then he got shipwrecked just as he was coming from Jerusalem to take a great chair at Padua. He died rather miserably.

-- George Eliot

Published on June 20, 2011 10:10

June 19, 2011

Woman bitten by rabid bat

'I hope my teeth don't get sharp': Woman bitten by rabid bat in terrifying attack | Mail Online:

"She managed to rip the bat out of her neck, but it was badly injured from the fly swat so she put it into a glass jar and tried to get back to sleep.

But the bat kept crying, she said, and she felt so guilty for electrocuting it she got up and put some air holes in the jar."

Published on June 19, 2011 06:40

Coyote hybrid attacks toddler on trampoline

WILD COYOTE ATTACK: Coyote hybrid attacks 3-year-old toddler on trampoline in Randolph County, North Carolina. - WGHP:

"The 100-lb attacker, which animal control officials dubbed a 'coyote hybrid,' grabbed Maggie by her shirt and began dragging her away."

This report mentions rabies, but the behavior sounds predatory to me--small human targeted, persistent attack. Apparently this animal is a hybrid of dog and coyote. The size mentioned here, if accurate, would be surprisingly for a coyote, but not for a dog. Wolf-dog hybrids have a history of hurting people. As dogs, they tend to be more comfortable approaching people than a wild wolf would be. I haven't heard of other coy-dog hybrids being especially dangerous.

Published on June 19, 2011 06:36

June 18, 2011

Hyena attacks boy

South African Tourism

South African TourismHyena rips tent, attacks boy - Times LIVE:

"Hudson was bitten in the face and head while he was in the tent with other pupils. The animal ripped the tent before attacking."

The photo included with this news story shows a spotted hyena. If that's really the species involved, there should be no mystery about the motive for the attack. Spotted hyenas eat people.

But perhaps the culprit is the brown hyena (pictured here) common in South Africa. This species is mostly a scavenger; it rarely kills animals as large as a twelve-year-old. It's a formidable animal which lives largely by intimidating leopards and other large carnivores, then stealing their kills.

Published on June 18, 2011 11:16

June 17, 2011

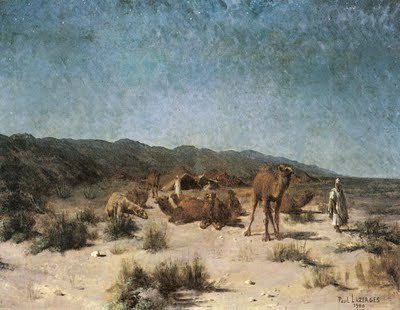

Camel bites baby at zoo

One dangerous animal that got short shrift in Deadly Kingdom is the camel. As a domestic animal, it has the same opportunities as cattle and horses to stomp, bite, throw, and otherwise harm people. However, I hadn't come across any memorable cases by press time. Now, thanks to reader Natan Slifkin, I can recitfy my omission. This first item finds the danger not on the job, but in the zoo:

Camel bites baby at zoo - Israel News, Ynetnews

And here's an older case that shows a camel in the role of road hazard. The same trouble occurs with whitetailed deer in North America, kangaroos in Australia, and a slew of species in Africa, from giraffes to elephants. An acquaintance recently returned from South Africa tells me she was warned about hippos on the road. Anyway, the Israeli camels:

http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/camel-causes-car-crash-that-kills-4-family-members-1.36394

Rabbi Slifkin's fascinating website is http://www.zootorah.com/. On arrival there, you'll see him riding an elephant, jumping a crocodile, and standing next to a bear. If you dig a little deeper, you'll find some fascinating scholarship.

Published on June 17, 2011 14:42

June 16, 2011

Rabid Beavers of Philadelphia

'Bizarre' Rabid Beaver Attacks Philadelphia Park Patrons | Wildlife, Rabies & Animal Attacks | LiveScience:

"A rabies-ridden beaver that wreaked havoc in a Philadelphia park, biting three residents over the last week, likely contracted the virus after a scuffle with a rabid raccoon."

A slideshow of some decidedly non-rabid raccoons:

Published on June 16, 2011 10:51

June 15, 2011

Death Stories: Slice, Part 4

Go to the beginning of this story

Earlier, we were sitting in Spitzer's office on the same floor. It seemed like a typical professor's lair--metal shelves neatly packed with books and journals, a desk stacked with papers. As we talked, Spitzer's beeper went off several times. He noted area codes he recognized so he could return the calls later. The unfamiliar numbers he ignored. He spoke with enthusiasm, but also with the ready examples and metaphors of a man who had explained his business many times. He used rhetorical questions as segues. "What do I mean by that?" he would say, and launch into the explication. The window behind him showed a glimmering ribbon of traffic bisecting the green swath of Denver, and behind that a mountain like a jagged molar.

It was during this conversation that Spitzer first mentioned the uniform tanness of cadavers. He was telling what parts of his work disturbed him on a visceral level. Although his first dissection ten years before was "traumatic," cadavers generally did not fit his category of disturbing things, and he posited that the reason was their dissimilarity from him. The typical anatomy-class cadaver represents the remains of a person seventy-odd years of age in some sort of poor health (otherwise they wouldn't be cadavers). Much of the muscle tissue has wasted. Embalming has leached the color and turned things the consistency of soggy leather. But when the cadaver happened to be closer to his own age, Spitzer started to feel unsettled. He told about the difficulty of "harvesting a leg" from an atypically fresh corpse. As for Jernigan, it wasn't disturbing at all to dismantle his corpse. Most of the time Spitzer and his colleagues were looking at no more than a frozen cross-sectional surface like the round steak.

Spitzer's vita shows diverse degrees--in chemistry, nuclear engineering, radiology, anatomy. "I didn't care what science I was in," he said. In his youth he dismissed biology because he thought it lacked definite answers. Medicine was worse: messy both epistemologically and otherwise. He preferred the mathematical accuracy of, say, chemistry. But the exciting work in chemistry was happening in the East. "I'm a Westerner," he said, and then added, "the West is more real." Radiology convinced him medicine could be studied with the sort of precision he liked. This discipline is, he pointed out, simply "slicing up bodies electronically"--while they're still alive.

*

Ancient Egyptian embalming techniques required that a corpse's belly be sliced open and the viscera removed. The priest who performed this particular task was chased out of the room afterwards and cursed, a ceremonial acknowledgement of transgression. This ritual encapsulates an attitude that has prevailed in the West for millennia: the interior of the body is taboo, but may be observed in certain highly controlled, ceremonial contexts. Such opportunities for observation arose in (to mention two historically diverse examples) the Medieval practice of searching the corpses of suspected saints for divine wonders (jewels or an unusual absence of rot) or in the Elizabethan practice of drawing and quartering supposed traitors.

Such events, however, contributed little to a systematic knowledge of the interior landscape. Even the limited forms of surgery performed in Ancient Greece occurred in a state of relative anatomical ignorance. The dissection of bodies for scientific or educational purposes began with Aristotle, who worked only on monkeys and other animals. The Greeks of his era found human dissection literally inconceivable—think of Antigone, a drama built entirely on the anguish of a sister for the mutilation of her brother's corpse. But Aristotle claimed that human anatomy could be largely deduced by analogy with that of other animals. He also advocated the observation of emaciated people, whose veins and bones stood out well enough to be mapped.

But colonial exploits brought opportunity. Human dissection was first practiced in the third century BCE in Alexandria, where the invading Greeks had fewer scruples about using the bodies of indigenous people. Physicians like Erisistratus and Herophilus cut into the corpses of criminals and non-Greeks. (Executed criminals have been a source for anatomical study ever since.) According to some accounts, they also performed vivisection on the living, on the theory dead bodies might differ too much from living ones to produce useful results.

The most important figure in early anatomy is Galen, a Greek physician of the the second century AD, who studied human dissection in Alexandria. After leaving Egypt, he worked on the carcasses of bears, lions, oxen, goats, and pigs. Even better were monkeys like the barbary macaque, whose parts he found to have "an exact similarity" to those of humans. He also studied the gaping wounds of gladiators, though he acknowledged that this method was not practical for most students. After Galen, the study of anatomy stagnated for a millenium.

Published on June 15, 2011 09:38

June 14, 2011

Death Stories: Slice, Part 3

(Go to the beginning of this story)

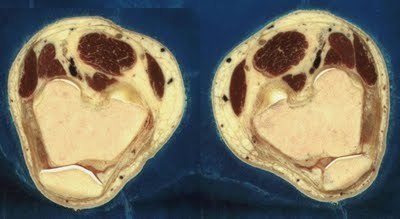

Victor Spitzer tossed something heavy and solid onto the table in front of me. "You can see it just looks like round steak," he said. It was a cross-section of a human thorax embedded in plastic. His description seemed right at first glance, but then he himself pointed out its limits. "This is what I was telling you about cadavers," he said. "Look at the color. Just uniformly tan." An effect of the formaldehyde, he added. He pointed out the lungs, which looked like shriveled bits of shiitake. They didn't fill their space. There were gaps.

I sat in a fifth-floor room at the Center for Human Simulation at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. The room felt geometric and grad-schoolish: white cinderblock walls, long wooden tables, a film screen, venetian blinds segmenting the tall windows. Now that Spitzer had brought them to my attention, I noticed a number of those transparent rectangles encasing human round-steaks strewn about the tables. He returned to the video he'd been running for me. It explained the Visible Human Project.

Spitzer -- 6 foot 4, age fifty, his blonde hair going gray -- wore sandals and khakis and a long-sleeved button-down. His manner was frank and friendly. He told me he had been in radiology at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center thirteen years before the anatomy department approached him with an idea about digitizing images of dead tissue. In the project that eventually developed, Spitzer, together with his partner David Whitlock and their team, sliced a human knee (and later a pelvis) thin and photographed the slices. These images, manipulated with computer technology developed for the Star Wars films and some Disney projects, became a new kind of anatomical information--more detailed, more realistic, than traditional anatomy texts and models. More true, because they hadn't descended from abstract ideas of human form. They were the thing itself captured in a camera. Spitzer liked photography for that reason: if the purpose of anatomy is to show what the body looks like inside, photography is a purveyor of exact truth.

Similar work was going on at medical schools across the country in the late 1980s. Scientists were sectioning hearts, skulls, and other popular body parts and digitizing their data in various ways. In 1989, the National Library of Medicine (NLM) got involved.

The NLM, which bills itself as the equivalent of the Library of Congress for medicine, launched the Visible Human Project. The plan was to develop the most complete set of anatomical data possible for two entire human bodies--one male, one female. The bodies of two volunteers would be turned into virtual cadavers, their bodies mapped into computers with a level of precision unprecedented. These computer models would then be available to anyone for almost any purpose. For example, the NLM anticipated that medical students would one day learn anatomy from the infinitely renewable electronic cadavers.

Spitzer and Whitlock competed for and won the NLM's contract. They began looking for a suitable male body. It had to be complete and relatively normal, a standard that eliminated most victims of accident and disease. It also had to be fresh. State anatomical boards in Maryland, Colorado, and Texas made bodies available for the project. Most of these donations were too old or too damaged to be useful. But one day the Texas board told Spitzer and his colleagues that a man on death row was nearly finished with his body and wanted it to go to science. Because he was to be executed by lethal injection, his organs couldn't be used for transplant. And because executions run on a schedule, the scientists could act within hours of his death, securing an unusually fresh body. Like several other promising corpses that turned up at about the same time, Jernigan's was air-freighted to Denver, where Spitzer's group put it through MRI and CT scans as if it were a live patient. In Jernigan's case, the body had to be "lightly embalmed" before its trip--infused with formaldehyde to counter the corrosive effects of the cocktail that killed him. Doctors at the NLM examined the images of three promising candidates. A suitable corpse needed to be "average," a term the NLM defined as aged twenty to sixty, under six feet tall, not obese, and free of serious injury or disease. (The problem, of course, was that people of that description are rarely dead.) In the end, Jernigan was judged most suitable, despite his missing appendix, tooth, and testicle.

Spitzer's group froze Jernigan's corpse in a block of blue gelatine and sawed it into four manageable chunks. The freezing was necessary because it makes even the most delicate tissues firm enough for sawing. Otherwise, some of them would become too messy to handle. "For example, the brain is not as tough as a tomato," Spitzer said. The quartering was necessary simply to fit the body into the equipment.

Next, using a rotary head suspended from the ceiling, they milled Jernigan's body, taking a thin slice from the bottom of his feet, then another a millimeter deeper, and so on. They cut him 1877 times. The body was photographed in cross-section after every cut. It had to be re-frozen at least every eight hours to maintain its solidity, so the process took months.

When it was over, the flesh-and-blood body of Jernigan had been reduced to ice shavings and ooze. Spitzer and Whitlock constructed a virtual body by collating the photographic images with the CT scans made earlier. Even though the actual body was photographed only in cross-section, the collated data can be "stacked" to show slices of the body in three dimensions. Almost any bodily structure can be examined on the virtual cadaver, provided you know where to look. Work now underway will label the parts, eliminating even that limitation.

Within three years, a refined version of this process had produced a virtual woman based on an anonymous 59-year-old donor who died of a heart attack. Both Visible Humans are available via the internet, though the enormous quantity of data (around 15 gigabytes) is too much for most home computers. But stills, snippets, animations, and simulations using the data are available at dozens of websites. The NLM and the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center both provide startling Web displays.

The video Spitzer showed me contained images like the ones I'd seen in my local university library, but larger and better: vivid, blood-glistening sections of flesh. Jernigan's entire body seemed to approach and pass through the plane of the screen, so I could see him progressively sectioned front to back. He was like a ghost vanishing through a wall. When I chose another angle, I could move from head to foot, the image kaleidoscoping—a blossoming of brain, a constriction of neck, a widening into the trunk packed with organs, a sudden bifurcation at the pelvis, and on down to the surprisingly dainty toes. Spitzer had made his point: the digital flesh came closer to life than actual embalmed flesh did. I ran my hand over the round steak in front of me, but felt only the smooth plastic casing.

(To be continued.)

Published on June 14, 2011 10:20

June 13, 2011

Mysterious mountain lion killed in Connecticut

Mysterious mountain lion killed in Connecticut - Yahoo! News:

"A mountain lion was killed just 70 miles from New York City early on Saturday morning and officials were trying to determine if it was the same big cat spotted a week ago roaming the posh suburb of Greenwich, Connecticut.

The 140-pound mountain lion was hit by a small SUV on a highway in Milton, Connecticut early Saturday morning, and died from its injuries."

Related Post: Cougar Found in Backyard

Published on June 13, 2011 09:19

June 12, 2011

Coyote Attacks Colorado Springs Woman In Her Backyard

ONLY ON 11 NEWS: Coyote Attacks Springs Woman In Her Backyard:

"'We looked at each other and I looked at his body and then he just pounced,' Kerwin said.

The coyote bit her twice before she could fight it off with a bag of potting soil, giving her just enough time to get to the stairs. Several reports say this animal has been spotted a number of times near the Fontmore area.

'He was very thin and had wiry hair, the eyes, and he didn't look well,' said Kerwin."

Published on June 12, 2011 10:33