Gordon Grice's Blog, page 56

May 15, 2012

Conrad and Me on the Radio

I was thrilled to have my first collaboration with James Addison Conrad, "Ebonsong," selected for Nik Nimbus's "Friends and Relations" episode on his Brighton and Hove Community Radio show, alongside great musical acts like like Radio Ray and Krankschaft. You can listen to the show here:

http://archive.org/details/NimbusHour_130512azx

And you can hear this and a couple of our other songs right here:

http://archive.org/details/NimbusHour_130512azx

And you can hear this and a couple of our other songs right here:

Published on May 15, 2012 01:30

May 14, 2012

Do Piranhas Eat People?

In The Book of Deadly Animals, I discussed the alleged man-eating proclivities of the piranhas. Everyone agrees that these fish occasionally bite people, mostly in territorial defense of their nests, and that these bites are no laughing matter. People have lost fingers and toes to them. But I was skeptical that they actually prey on people. In researching Deadly Animals, one of the first claims for anthropophagy I came across was this, from a 1994 edition of the Guinness Book of Records:

In The Book of Deadly Animals, I discussed the alleged man-eating proclivities of the piranhas. Everyone agrees that these fish occasionally bite people, mostly in territorial defense of their nests, and that these bites are no laughing matter. People have lost fingers and toes to them. But I was skeptical that they actually prey on people. In researching Deadly Animals, one of the first claims for anthropophagy I came across was this, from a 1994 edition of the Guinness Book of Records:"On 19 September 1981 more than 300 people were reportedly killed and eaten when an overloaded passenger-cargo boat capsized and sank as it was docking at the Brazilian port of Obidos. According to one official, only 178 of the boat's passengers survived."

But this claim was hard to substantiate. It seems to have originated in a sensationalist newspaper. A later edition of the Guinness Book did not repeat the claim, which seemed a telling omission. A web search turned up dozens of copies of this same brief Guinness Book snippet, often with different numbers. Other stories of mass predation were similarly elusive.

After an earlier post of mine, Croconut mentioned a claim in the River Monsters TV show that piranhas do in fact take children. I watched the episode and found it very interesting, but also frustrating; it is marred by the usual sensationalism of TV documentaries. In one sequence, for example, the show dramatizes a case of piranhas attacking swimmers on a beach in the style of Jaws. In Jaws, of course, people get eaten; in the real-life piranha case, they were merely driven away from piranha nests with sharp nips. I feel the sequence is misleading. Host Jeremy Wade discusses the case of a bus that plunged into a river. As legend has it, many passengers couldn't escape and were eaten by piranhas. To his credit, Wade takes a skeptical approach and concludes the piranhas may have simply scavenged the drowned bodies, rather than preying on live ones.

The most important part of the show for our purpose is Wade's interview with a man whose two-year-old grandson fell into a river and was eaten by piranhas. It's also the most frustrating part, because instead of hearing the grandfather's words, we get Wade's emotional summary of them. I hate this kind of stuff. TV producers seem to think we need to see everything filtered through our hero. Why not show the guy who was directly affected and translate his account as plainly as possible? Could it be because the producers don't trust a North American audience to connect with a non-white subject?

I looked at Wade's book version of River Monsters: True Stories of the Ones that Didn't Get Away

and was pleased to see it didn't suffer from the same sort of manipulation. Wade says the image of piranhas skeletonizing their prey in minutes enters Western culture through Theodore Roosevelt's account, which he briefly cites. Here's Roosevelt's spiel at greater length:

and was pleased to see it didn't suffer from the same sort of manipulation. Wade says the image of piranhas skeletonizing their prey in minutes enters Western culture through Theodore Roosevelt's account, which he briefly cites. Here's Roosevelt's spiel at greater length:Late on the evening of the second day of our trip, just before midnight, we reached Concepcion. On this day, when we stopped for wood or to get provisions—at picturesque places, where the women from rough mud and thatched cabins were washing clothes in the river, or where ragged horsemen stood gazing at us from the bank, or where dark, well-dressed ranchmen stood in front of red-roofed houses—we caught many fish. They belonged to one of the most formidable genera of fish in the world, the piranha or cannibal fish, the fish that eats men when it can get the chance. Farther north there are species of small piranha that go in schools. At this point on the Paraguay the piranha do not seem to go in regular schools, but they swarm in all the waters and attain a length of eighteen inches or over. They are the most ferocious fish in the world. Even the most formidable fish, the sharks or the barracudas, usually attack things smaller than themselves. But the piranhas habitually attack things much larger than themselves. They will snap a finger off a hand incautiously trailed in the water; they mutilate swimmers—in every river town in Paraguay there are men who have been thus mutilated; they will rend and devour alive any wounded man or beast; for blood in the water excites them to madness. They will tear wounded wild fowl to pieces; and bite off the tails of big fish as they grow exhausted when fighting after being hooked. Miller, before I reached Asuncion, had been badly bitten by one. Those that we caught sometimes bit through the hooks, or the double strands of copper wire that served as leaders, and got away. Those that we hauled on deck lived for many minutes. Most predatory fish are long and slim, like the alligator-gar and pickerel. But the piranha is a short, deep-bodied fish, with a blunt face and a heavily undershot or projecting lower jaw which gapes widely. The razor-edged teeth are wedge-shaped like a shark's, and the jaw muscles possess great power. The rabid, furious snaps drive the teeth through flesh and bone. The head with its short muzzle, staring malignant eyes, and gaping, cruelly armed jaws, is the embodiment of evil ferocity; and the actions of the fish exactly match its looks. I never witnessed an exhibition of such impotent, savage fury as was shown by the piranhas as they flapped on deck. When fresh from the water and thrown on the boards they uttered an extraordinary squealing sound. As they flapped about they bit with vicious eagerness at whatever presented itself. One of them flapped into a cloth and seized it with a bulldog grip. Another grasped one of its fellows; another snapped at a piece of wood, and left the teeth-marks deep therein. They are the pests of the waters, and it is necessary to be exceedingly cautious about either swimming or wading where they are found. If cattle are driven into, or of their own accord enter, the water, they are commonly not molested; but if by chance some unusually big or ferocious specimen of these fearsome fishes does bite an animal—taking off part of an ear, or perhaps of a teat from the udder of a cow—the blood brings up every member of the ravenous throng which is anywhere near, and unless the attacked animal can immediately make its escape from the water it is devoured alive. Here on the Paraguay the natives hold them in much respect, whereas the caymans are not feared at all. The only redeeming feature about them is that they are themselves fairly good to eat, although with too many bones.

It's interesting, but Roosevelt has no specific case of anthropophagy to cite. Presumably he took the claims of local people at face value.

As in the TV show, Wade debunks the bus wreck as a case of mass predation. He also alludes to the Obidos incident and says he, too, was unable to confirm it.

And what about the fatal attack on a two-year-old? Wade briefly repeats that story in the book, this time without the TV-emoting. I felt hungry for more information on this incident, but I have no reason to doubt its truth.

Published on May 14, 2012 01:30

May 13, 2012

Bee Hive

Published on May 13, 2012 02:00

May 12, 2012

Leopard Implicated in Death of Child

Body found, leopard attack suspected - Indian Express:

"Police found the body after a resident of Adarsh Nagar village in Aarey Milk Colony at Goregaon (East) informed them about having seen torn clothes and remains of a body when he had gone into the woods to relieve himself.

Police suspect that the child may have been mauled to death by an animal, possibly a leopard."

Published on May 12, 2012 01:46

May 11, 2012

Hyenas Maul 17

If this really is a single hyena, rabies would be the likely cause for multiple attacks of this sort. The people managed to kill one animal.

If this really is a single hyena, rabies would be the likely cause for multiple attacks of this sort. The people managed to kill one animal. allAfrica.com: Tanzania: Hyenas Wreak Havoc in Karatu, Injure 20: "so far the authorities in Karatu have confirmed that a total of 17 people have been hurt from the weekend ordeal.

The first victim was a lady, Ms Filomena Richard whose house is located adjacent to a deep gorge from which one of the beasts is reported to have emerged from. The hyena reportedly took a bite from Ms Richard's arm before running away when the lady started to scream for help.

When villagers gathered around the house, it was already dark and as they discussed how to start hunting down the animal, there was another attack right within the group as the hyena or a similar beast jumped onto one of the villagers.

After that, the hyena(s) continued to launch attacks to unsuspecting villagers at different times of the night, leaving a trail of nearly 20 victims in the scary weekend night."

Published on May 11, 2012 01:35

May 10, 2012

Attack of the Ticks

Deer tick, a vector of Lyme disease

Deer tick, a vector of Lyme diseaseby guest writer Kimberlee Smith

You will seize up with fear when your children dive into piles of leaves in autumn.

You will holler at them to stop that right away, because they know better. They know about the ticks. They are taught about Lyme disease in school and at home. They live at ground zero, one of the densest areas of Lyme disease documentation anywhere.

You will bark at them again for sitting on the century-old low stone wall that you know makes a perfect launching pad for the pernicious arachnid, no larger than the size of a period at the end of a sentence in newsprint. The nearly invisible pest. Nearly, until you undress to soak in the bath and feel an angry, hot burn on your lower hip. You touch it; it feels like a third degree burn. It looks like there is a ruby red grapefruit fused to your hip.

You scratch and scratch until it turns purple and furious and now has raging nail marks on the grapefruit skin that is your own body. You slap at it, the stinging of your flat palm eases some of the searing itch.

You don’t have time to tell anyone. You race to the town walk-in clinic, a triage center. The elfin doctor with the wide grin might be a woman or a man, but you do not care. You suggest to the doctor the super-welt might be a spider bite. The doctor’s frozen smile stays pasted to the doctor’s face.

The doctor suggests it is a poison ivy rash. You are highly allergic to poison ivy and know this is not it. Because you know it well, having taken shots to desensitize your system to the ivy oils since you were a teenager. Since you went to the bathroom in the woods because you were drinking beer with your friends and wiped yourself with poison ivy. You did not get a tick bite up your ass, but you did get a severe allergic reaction to poison ivy in every orifice—every one--and a trip to the hospital and weeks of antibiotics.

So you know it is not that. The doctor prescribes a five-day pack of Zithromax and Prednisone, which you do not, cannot, take, because it makes you crazy angry like a television wrestler with roid rage.

You are staple-gunning plastic sheeting to the frames of the screened in porch. It is several months since the grapefruit has left your hip. But you are infected. As with most diseases, the symptoms are the alarm bells, and you are at a well-advanced stage of illness that takes aggressive treatment. But you do not know this, not yet.

Your muscles ache, your joints feel as if all the fluid has drained out and bone rubs against bone, that after 42 years, you might well now begin suffering from migraine. That you might have the flu. Mononucleosis? Lupus? Epstein-Barr? That you should put down the staple gun and have a hot tea. You do, and you sleep. And it hurts.

You call the internist from Yale, referred by one of your many friends who have suffered from Lyme disease. You drive to see him. He is a specialist. He runs all the tests, vial after vial. He does something called a Western Blot test. Across the board for autoimmune illnesses. You think maybe it is AIDS. That you are dying. But it is not, thankfully, and you are not.

The wonderful doctor who is young and handsome and most definitely male puts you on a month of antibiotics and declares without waiting for the test results, that you most probably have Lyme disease. You want to hug him, you want to cry.

You spend the next two weeks with your children tending to themselves and your home is not unlike a scenario from Lord of the Flies. You wave from the kitchen window as your children get on the school bus. You go back to sleep and wake when they come home. The dogs haven’t been fed, but they shit on the floor anyway because you did not have the energy to let them out. Your kids eat instant macaroni and cheese and microwave hotdogs. You assure them you will be fine, but still everyone is scared, and now and then you all cry.

Two weeks later, your mouth is doughy and bleeding from thrush from the antibiotics. But you wake up. Feeling better, but that feeling better is relative, because you felt like you were run over by a Boeing 777. Slowly.

The test comes back inconclusive. But it often does, the wonder doctor assures you. You have Lyme disease, but we will get you better. We will, together. You love this doctor almost as much as you loved your obstetrician who brought your babies into the world.

You are better. Ish. But there are cases of relapse.

You are afraid of grass. Bushes. Trees. Shady, verdant spots at which you used to daydream and count clouds, carefree.

You are afraid of outside your own back door. You hate grass and springtime and the great outdoors. You are furious with it for being a breeding ground for the deer tick, this arachnid that spreads Lyme disease to you.

Your dogs will whimper and whine and dig deep holes in your yard because they are bored. You will cuss at them; maybe give them too many treats. They will get thick in the middle and become despondent. They miss the hikes in the woods, they miss you kicking the ball in the meadow to them.

You will make sure, if you ever again get up the nerve to hike through the woods right out your back door, you will wear long socks and tuck your pants in to them. And high boots laced so tight your feet go numb. And long sleeves with rubber bands around your wrists so those sneaky little bastards cannot invade you again. A hat. Gloves. Head-to-toe DEET spray. But chances are you will never hike again.

The dogs are immunized against Lyme. You topically apply a liquid that kills the tick if it latches on your dogs. For you? There is nothing. Nothing prophylactic, no preventative. Only treatment once you are infected. You will always feel afraid it will happen again, you are always going to be vulnerable. You have so many friends who have contracted Lyme, you know more people who have than who haven’t, living here in rural Connecticut. You think you should move to the city.

Instead you worry, you inspect your children, and they, you, looking for that tiny dot that could render you paralyzed and neurologically impaired—potentially irreversibly. You are paranoid, and you should be. Lyme disease is sneaky, and relentless. It rides on the backs of deer, it travels on mice, it lives on dogs. Mainly, it lives on blood. Yours, because you know it was there, firsthand.

Published on May 10, 2012 01:12

May 9, 2012

Giants in the Earth

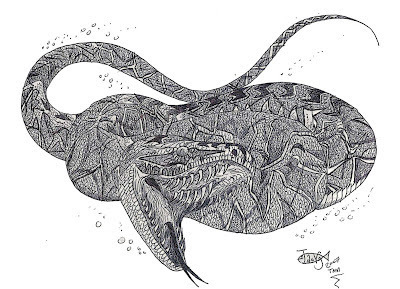

Madtsoia

MadtsoiaIn this conclusion to a three-part series, guest writer and artist Hodari Nundu looks at the biggest snakes in the history of the planet.

Even though pythons and boas may have grown larger a few decades ago, even the largest dragons of our days would look like garter snakes compared to some of the monstrous snakes that lived millions of years ago.

Scientists believe that snakes appeared around 120 million years ago, in the Cretaceous period- the golden age of dinosaurs. Although it is tempting to imagine gigantic snakes coexisting with dinosaurs and giant crocodiles, the truth is that evidence for such creatures is scarce. In fact, to my knowledge, the only giant snake known from the Cretaceous is a species of Madtsoia whose remains were found in Madagascar.

Madtsoia was a constrictor, like pythons or boas, but it wasn´t closely related to them. Instead, it belonged to its own family, Madtsoiidae, which was seemingly well represented and widely distributed during the late Cretaceous and even survived the mass extinction at the end of said period. Madtsoiids probably looked a lot like pythons, but they were different in several ways, the most important being that their jaws couldn´t unhinge the same way a python’s jaws do. In other words, madtsoiids, even the larger ones, couldn´t swallow prey as huge, relative to their own size, as modern day constrictors.

Madtsoia tackles Majungasaurus, a 20-foot cannibal of the Cretaceous

Madtsoia tackles Majungasaurus, a 20-foot cannibal of the CretaceousUnfortunately for those of us who like to imagine epic prehistoric duels, this means that there were probably no dinosaur-eating snakes, or at least, no giant-dinosaur eaters. Madtsoia madagascariensis is known only from fragmentary fossils, but scientists believe the original specimen was at least 5 meters long- pretty respectable for any snake, and there are vertebrae from other specimens suggesting an even larger potential size for the species- maybe up to 8 meters long. At such size, Madtsoia would probably be able to constrict many large dinosaurs to death, but if it was, as scientists say, unable to swallow large prey, then this seems unlikely to have happened often. Smaller dinosaurs were another story, of course, and there’s some evidence in the fossil record that madtsoiids may have fed on dinosaur eggs and hatchlings; in India, the remains of a 3.5 meter long relative to Madtsoia, named Sanajeh, were found along with the nest of a long necked dinosaur; the snake had seemingly been waiting on the nest for the little dinosaurs to hatch, ready to dine on them.

Madtsoia takes Masiakasaurus, a six-feet flesh-eating dinosaur

Madtsoia takes Masiakasaurus, a six-feet flesh-eating dinosaurThe madtsoiid lineage lasted until very recently, geologically speaking; the last member of the family, called Wonambi, stalked the waterholes in the Australian desert until 50,000 years ago, meaning this six meter giant was encountered (and quite possibly, eventually exterminated) by the ancestors of modern day Australian aborigines. Some scientists say that Wonambi itself may have preyed on human children once in a while, partially explaining why even today, aborigines instruct children to keep away from waterholes-- no matter how shallow -- unless accompanied by an adult. Any smallish animal that came close to the water would’ve been fair game for Wonambi.

But the fossil record has evidence of serpents much bigger than these.

In 1901, the remains of a gigantic snake were found in Egypt. Dating back to 40 million years ago, Gigantophis, as it was named, was the largest snake known to science for a long time. Originally considered to be a “boid,” related to boas and pythons (today pythons are classified as a separate family), Gigantophis is now known to have been a madtsoiid, just like Wonambi. It was, however, much bigger; even though its remains are fragmentary, they suggest a length of at least 10 meters.

This makes Gigantophis as big as the biggest reported reticulated pythons, and certainly much bigger than any confirmed giant python in modern times. What this giant snake ate is still a mystery. The remains of primitive, pig-sized elephants and other creatures have been found in the same fossil sites, but if Gigantophis was unable to unhinge its jaws like a python, these creatures may have been too much to handle. It is possible that it was a fish eater, though; back then, the region of Egypt where it lived was not a desert, but a coastal swamp. It is possible that Gigantophis spent a lot of time in the water, like modern day anacondas. Alternatively, it may have preyed on water birds or perhaps on other, smaller reptiles. At about the same time, the sea was home to other giant serpents.

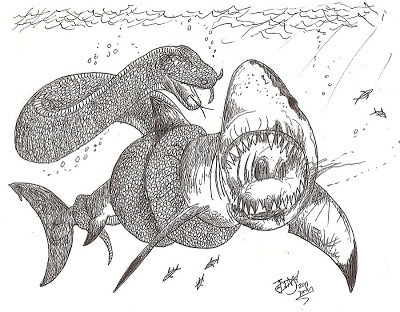

Paleophis vs. Otodus, an ancient shark related to the great white

Paleophis vs. Otodus, an ancient shark related to the great whiteOne of them, Palaeophis, could grow up to 9 meters long, and was probably a denizen of estuaries and coastal waters. A close relative of it, Pterosphenus, was even better adapted to a marine lifestyle, with a laterally flattened tail just like modern day sea snakes. But unlike our venomous sea snakes, related to cobras and kraits, Pterosphenus was probably a non-venomous fish eater, measuring up to 7 meters long-- over three times larger than the largest modern day sea snakes. Unfortunately, there’s no way to know if this giant could obtain part of its oxygen directly from the water, like some modern day sea snakes do.

Neither Palaeophis nor Pterosphenus could slither on land; they were completely transformed into aquatic animals. They were, as we would say in my country, sea serpents with all their letters.

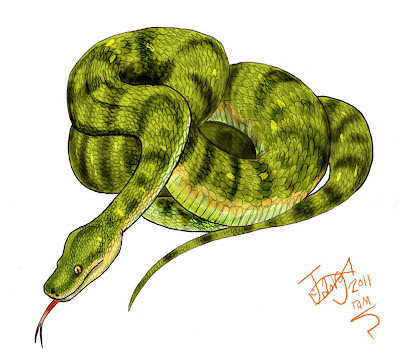

Liasis dubudingala

Liasis dubudingalaAll around the world, the fossilized remains of other giant snakes have been found. One of the most interesting is now known as Liasis dubudingala, and was found in Australia. But unlike Wonambi, which coexisted with human beings, L.dubudingala lived 4.5 million years ago, long before humans reached Australia, or even before they evolved at all. This snake still has living relatives today; one of them, the olive python or Liasis olivaceus, is Australia’s second largest snake, measuring up to 4 meters long. But even this respectable snake was dwarfed by its prehistoric relative, which was just as long as Gigantophis- 10 meters long.

Unlike the heavy, probably aquatic Gigantophis, however, Liasis dubudingala was seemingly a tree dweller; some of its skeletal features are highly reminiscent of those of modern day tree snakes. It is possible that this giant tree python relied on camouflage to hide in the canopy, waiting in ambush for some unfortunate bird or arboreal marsupial to come close to its deadly coils; indeed, the word dubudingala means “strangling ghost.” I am always tempted to imagine it as being bright green, like tree pythons or emerald boas; there is, of course, no way to be sure about this.

Titanoboa takes a Coryphodont, a primitive mammal

Titanoboa takes a Coryphodont, a primitive mammalUnfortunately, Australia’s awesome giant tree python was overshadowed by a 2009 discovery; in a coal mine in Colombia, the remains of a snake even bigger than either Gigantophis or Liasis dubudingala were found, and quickly became headlines around the world. Compared to the equivalent bones in a modern day anaconda, those of the Colombian snake were humongous; scientists estimated that, when alive-- 60 million years ago-- this snake was probably between 13 and 15 meters long, being, they said, “the largest snake ever to have existed.” They named the creature Titanoboa, for it was not a python, nor a madtsoiid, but a member of the Boidae family, the same family that includes modern day boa constrictors and anacondas. The implications of this can send shivers down one’s spine; this was a giant snake that could unhinge its jaws and swallow enormous animals. The coal mine even provided a glimpse to the possible menu of Titanoboa; enormous freshwater turtles and crocodiles, suggesting that Titanoboa was probably a water based animal.

It makes sense if we consider the snake’s incredible weight; up to 1,135 kg. The heaviest snake of our times, the South American green anaconda, weighs only a small fraction of this, and yet it’s so massive that its movements are slow and clumsy on dry land. It is in the water where the anaconda becomes quick and deadly, taking its victims by surprise. Titanoboa may have been the same.

If we had a time machine and could bring an adult Titanoboa to the modern world, it would be seen as a monster of almost absurd proportions. Scientists themselves have said some pretty fantastic things about it. They have described it as the T-Rex of snakes, and have actually labeled it a worthy foe in a hypothetical fight between these two giant reptiles. They have suggested that it would have trouble to go through a normal sized office door, because of its titanic girth. And a reptile curator from the Smithsonian Institute said that if Titanoboa was alive and kept in captivity, it would probably have to be fed on cows. I myself remember my days as a zookeeper and, considering the strength of modern day pythons and boas, and their proclivity to escape from their terrariums, I think keeping a Titanoboa in captivity would be a catastrophe just waiting to happen. There’s no way any number of keepers could hold a Titanoboa still like we did with Aphrodite. It would simply be too powerful.

***

Perhaps the most frightening and awesome part of the story is that, although pretty much every source today describes Titanoboa as the largest snake of all times, the truth is that we know too little about the fossil record to make such claims.

There may very well be larger monsters out there, fossilized in the rocks, waiting to be discovered. What’s more, we may already have found some of them. Some post-Cretaceous species of Madtsoia have been described as being perhaps as long as Titanoboa, and in 1993, there were rumors that the fossils of a colossal snake had been found in Argentina, surpassing Gigantophis (back then considered the largest snake of all times) and Madtsoia in size. According to at least two paleontologists, this snake, known as Chubutophis grandis, may have reached a mind blowing length of 15 to 20 meters long! There is even one mention of a 29 meter long fossil snake also from Argentina (and potentially the same as Chubutophis), but some paleontologists believe this estimate was due to a typo, and that the author probably meant 20 meters.

Still, it is hard to imagine the size and might of such a beast, and even harder to imagine what it would feed on. To most of us, such a monster would make more sense in the Age of Dinosaurs, when the size of potential prey was more fitting for such a monstrous predator. But as I say, we only know part of the story.

Both living and extinct, dragons remain mysterious; there’s still a lot to learn about them. They may not fly or breathe fire, or guard treasure; but the point is, they are real. We just gave them a new name, and kept the old one for the legend.

Published on May 09, 2012 01:38

May 8, 2012

Man-Eating Snakes and Other Giants

Guest writer Hodari Nundu explores the biggest snakes on the planet. This is the second in a three-part series.

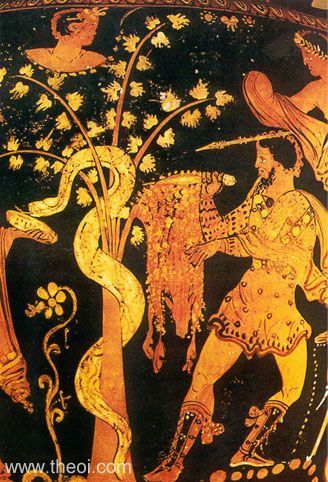

So, now we know that dragons were originally snakes, and that python snakes seem like the obvious source of the myth, at least in Western countries (although Eastern dragons were also originally snake-like, and were later adorned with small lizard-like limbs, crests and whiskers). Does this mean that the dragon that protected the Golden Fleece was also a python snake? Or the one worshipped as a living god in Babylonia, according to the Bible?

4th Century BCE image, with Jason stealing the Golden Fleece from a snake-like dragon

4th Century BCE image, with Jason stealing the Golden Fleece from a snake-like dragon 17th-Century painting by Salvator Rosa; the dragon has grown legs.

17th-Century painting by Salvator Rosa; the dragon has grown legs.I think it’s likely. In 2006, archaeologists announced that they had found evidence of the oldest cult known to science in a cave in Botswana; this cult, over three thousand years older than the oldest known from Europe, had the python snake as its central deity. Even today, 70,000 years later, many African tribes still worship the python as a symbol of life, fertility and transformation. The same is true for some tribes of Southeast Asia.

What is it about the python that inspires such worshipping? I think it’s obviously their size and power.

During my brief time as a zookeeper I had a few experiences with captive pythons of several species, but mostly, with the spectacular Burmese python. Kaa, the enormous and wise snake from Kipling’s stories, belonged to this species. Most large snakes used in Hollywood movies are Burmese too.

But although Burmese pythons are the favorites of zookeepers due to their relatively docile demeanor, they are not to be underestimated. Their strength, even when they are young and relatively small, is incredible. I learned this when one of the zoo’s Burmese pythons, an albino female named Aphrodite, developed an infection around its mouth (a very common disease among captive snakes, technically known as ulcerative stomatitis).

The vet needed to apply antibiotics on the snake’s mouth, but he needed several people to hold the snake still on the operation table. It wasn’t an easy task. Aphrodite was good tempered, but as soon as the antibiotics touched her infected skin, she started to thrash and squirm with incredible force, obviously in great pain. It took no less than four men, including myself, to hold the snake still long enough for the vet to apply the antibiotics. Today, Aphrodite must be a very large python; but back then, she was barely three meters long. I can only imagine what it must be like to wrestle a reticulated python over three times that size; it is no wonder that even leopards and sun bears fall victim to their coils.

In another occasion, the senior keeper in the zoo ran out of terrariums, and he urgently needed to contain a new addition to his collection--a boa constrictor, a distant relative of pythons and the largest snake in my home country. In the end, he decided to put the boa in with a Burmese python of docile temperament. It was a mistake. The python launched such a vicious attack on the boa that the latter had to be rescued immediately. It survived, but barely; the python had bitten it repeatedly leaving enormous, bloody wounds on the unfortunate boa’s flesh.

Now, the teeth of a python are not designed to slash through flesh; they are simply grappling hooks, to hold on to the prey during constriction, and they also play a part during the swallowing of prey; but the python was seemingly not trying to eat the boa- instead, it reacted defensively, seeing the other snake’s presence as a threat to itself or its territory. A python’s bite can be potentially as dangerous as that of a venomous snake; the risk of infection is extremely high. That was, of course, the last time the senior keeper tried to put boas and pythons together in the same terrarium.

Burmese Python by Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble/Creative Commons

Burmese Python by Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble/Creative CommonsSo pythons are big, strong and dangerous. They are strong swimmers and skilled tree-climbers. And although there is some evidence that pythons may be “shrinking”-- that is, they no longer reach the huge sizes they were famous for, mostly because humans no longer allow them to live long enough-- they are still very large snakes, and they still kill people once in a while.

In 2002, a child was collecting mangoes on an orchard in South Africa along with some friends, when he was suddenly attacked and strangled by an African rock python. It took the snake three hours to swallow the 10-year-old; his friends, who had climbed up a tree for safety, witnessed the whole process, and only climbed down when the snake slithered into a nearby stream and disappeared. The authorities said that it was the first instance known of an African rock python eating a person, at least in modern times.

Experts say that pythons are very unlikely to attack humans, and even when they do attack and kill someone, they don´t always eat their victim. Some say the shoulders of a human are too wide for even the largest snakes to swallow; others say that the snakes dislike our smell, and an interesting theory I learned of recently says that it’s not that they dislike our smell per se, but rather that of the cosmetics and chemical products we use.

Even so, pythons are opportunistic eaters, and if they are hungry, they are likely to launch an attack regardless of what species their prey belongs to; they have been known to kill and constrict animals that are too big for them to swallow. Their gluttony often ends up badly for them; in 2006, a reticulated python in Malaysia found itself in trouble when it swallowed a pregnant sheep. Even though the snake was 5.5 meters long, it was unable to cope with such a monstrous meal-- it eventually had to regurgitate the sheep to be able to move again. A Burmese python in Florida wasn´t so lucky; it swallowed an alligator so large that the snake seemingly burst open afterwards. There’s also a famous story of a python that was shot while trying to swallow an adult man; apparently, the snake had swallowed the head of the man but had became stuck on the shoulders. Interestingly, this gluttony is a common theme in many ancient dragon stories, and it often spells the dragon’s doom.

Other than its man-eating tendencies, the most controversial issue about pythons today is their maximum size. It is often said that the largest reticulated pythons-- usually considered the longest snakes in the world-- reach up to 10 meters long. Due to lack of solid proof, however, many scientists are skeptic about this. In modern days, no such monster has been seen, and the largest pythons are usually around seven meters long. Even these giants-- fed in captivity with goats and dogs-- are very uncommon.

I don´t think this is surprising, though. The world has changed a lot since the days of Python of Parnassus. Rainforests in Africa and Asia are more and more fragmented each day. In Africa, rock pythons are hunted in large numbers for their meat, or for their body parts, used by witch doctors for potions or amulets. In Asia, pythons are considered dangerous or mistaken for venomous snakes and often killed on sight. Many of these pythons are young; very few have the chance to reach truly enormous sizes. It seems very significant to me that the more we go back in time, the larger snakes are in reports, tales and legends.

In Mexico, my home country, the elders still tell stories about gigantic boa constrictors. They claim that a long time ago, when the forests were still large and rich in wildlife, boas grew to phenomenal sizes. My own grandfather used to tell of his own close encounter with a monster snake. He was driving with another man-- I don´t remember if it was a relative or a friend-- through the densely forested state of Chiapas, when suddenly the car hit something in the road.

They thought at first that it had been a speed bump, but almost immediately they reasoned that such a thing didn´t make any sense in such a lonely road in the middle of the jungle. They stopped the car and walked back to the “speed bump,” only to realize that it was a gigantic snake crossing the road. Amazingly, it hadn´t been injured, or at least, it didn´t seem too badly hurt. It continued to slither across the road slowly and eventually disappeared into the jungle. According to him, the snake must have been around ten meters long.

Of course, if you ask a herpetologist, he will tell you that boas rarely grow to four meters long and would certainly never grow to over six meters long. Giant boas are the product of exaggeration, bad measuring techniques and ancient legends mixed with the natural fear country people have of snakes.

They will also tell you that the ancient Mexican name for the boa constrictor, mazacoatl, “deer snake”, comes from a mythical creature that was half snake and half deer. But the elders are more practical; they say the boa is called mazacoatl simply because it eats deer. And it takes a gigantic snake to eat even the relatively small Mexican white-tailed deer.

So, who’s to be believed?

Published on May 08, 2012 03:24

May 7, 2012

Giant Snakes

Could the dragons of myth have been gigantic snakes? Guest writer Hodari Nundu explores our ancient connection with the biggest snakes. This is the first of a three-part series.

I love dinosaurs. Everyone knows I love dinosaurs. I draw them all the time. My old school notebooks have more dinosaur drawings and doodles than actual homework notes. Some of my teachers hated me because of this. Others would regularly want to borrow my notebook just to take a look at the drawings. One of them, an old lady with the visual acuity of a mole, would sometimes adorn my drawings with a check mark, although I could never find out if she was mistaking them for school work or if she was actually a fan of my work expressing her approval in her own, teachery way.

Because of this obsession of mine with dinosaurs, I’ve come to learn quite a bit about them, meaning that I often find myself answering the questions of curious people about these mysterious creatures.

One of the most common questions I get is if I think dragons really existed one day. I suppose everyone wants me to say that dinosaurs and dragons are somehow the same thing, and so they are quite surprised when I answer starting with another question.

“Do you know what the word “dragon” means?” I ask. They usually say no, and then I explain that dragon comes from ancient Greek “drakon”, meaning “serpent” or “snake”. Indeed, dragons (at least in the Western world) were originally conceived as giant snakes, not as dinosaur-like, fire-breathing winged beasts.

In Greek myth we find plenty of stories involving these snake-like dragons. One of the most famous examples is Python. This particular dragon (some say there were actually two) lived in Mount Parnassus, where it was seemingly worshipped as a deity. There are several versions of this myth, but they all end the same way; the Olympian god Apollo takes over Mount Parnassus and slays Python with his arrows. He then has the serpent’s shrine replaced by his own. Due to the dragon’s divine nature, however, there were a series of rituals Apollo had to perform in order to keep Python’s spirit appeased.

Representations of Python always show him as a giant snake. Some historians, however, believe that the myth of Python must not be taken literally. Instead, they think the story is a metaphor for an ancient religious revolution; some even go as far as to saying that both Apollo and Python were originally humans--leaders of different religions or cults--and that the metaphor of the god slaying the dragon represents the triumph of one of said leaders over the other.

Personally, I believe that the story works just as fine when taken literally. It is possible that there was a dragon in Mount Parnassus, worshipped as a god in a shrine, tended by loyal priestesses. Snakes have been worshipped as gods in many cultures, and there’s plenty of evidence of a snake cult in Greece before the Olympian gods, so to speak, “came into power.” But of course, not just any snake can be a dragon.

My answer to those who ask me about dragons is always the same. “Yes, dragons did exist, and they still do exist. You have seen them in the zoo, and perhaps you even keep one as a pet”. Today, we call them “python snakes,” after the one that was worshipped in Mount Parnassus.

Photo by Parker Grice. Reticulated python provided by Twin Cities Reptiles.

Photo by Parker Grice. Reticulated python provided by Twin Cities Reptiles.

That the mythical dragon slain by Apollo gave its name to some of the largest and most spectacular snakes today-- including the longest snake in the world, the reticulated python of South East Asia-- is no surprise. But people still are taken aback when I tell them my theory about pythons themselves being the inspiration for the myths of the Western dragons. Everyone wants dragons and dinosaurs to be the same!

The evidence for my hypothesis is plentiful, though. Greek and Roman historians, travelers and naturalists said once repeatedly that dragons were real, and that they were snakes of great size and might. Some of them were incredibly accurate in their descriptions. Most mentioned India and Ethiopia as the homelands of dragons; tropical Asia and Africa are indeed the home of the largest pythons. Even later in History, many authors describe python snakes calling them “dragons.”

Isidore of Seville said that dragons were the largest kind of serpent. St. John of Damascus said that “dragons do exist, but they are snakes born from other snakes… they are small when they are young, but then… they exceed all other serpents in length and are as thick as a huge log.” Perhaps most telling is the fact that instead of killing with venom (or fire), these original dragons killed by constriction- squeezing the life out of their prey with their powerful coils. Pliny the Elder said that dragons would battle with elephants, eventually constricting the poor pachyderms to death; but these titanic duels were also deadly for the dragon, Pliny said, for the elephant would collapse and crush its reptilian adversary under its weight.

Now, an elephant is way too big for a python to tackle, but the fact remains that the largest pythons do attack, constrict and devour pretty formidable prey; the remains of deer, sheep, wild boar, leopards and sun bears have all been recovered from the stomachs of reticulated pythons, for example. And once in a while, they’ve been known to kill humans too. It seems pretty evident to me that python snakes, ironically named after a dragon, were originally the inspiration for the dragon itself.

Native to warm countries, and often highly dependent on water, pythons would’ve been very difficult to transport and keep alive in Europe; but we do know that in Roman times, some of them were successfully kept and exhibited as curiosities in the Colosseum.

Is it possible, then, that some python snakes were captured earlier, either from Africa (there was a time in which African rock pythons were found in Egypt) or Asia and taken to Greece? In a country in which snakes were already considered sacred, it is not difficult to imagine a large python being kept as a living god in a shrine like that of Mount Parnassus. Interestingly, the shrine of Python was located over the Kerna spring waters, which flowed under the temple both keeping it warm and filling it, it is said, with strange fumes. Is it possible that these unique conditions created a sort of terrarium-like environment in the temple, allowing for the dragon to survive for many years and therefore attaining very large size?

Maybe someone did slay a dragon in Mount Parnassus. Maybe the bones of a large python snake will one day be found by archaeologists studying the site. Who knows?

I love dinosaurs. Everyone knows I love dinosaurs. I draw them all the time. My old school notebooks have more dinosaur drawings and doodles than actual homework notes. Some of my teachers hated me because of this. Others would regularly want to borrow my notebook just to take a look at the drawings. One of them, an old lady with the visual acuity of a mole, would sometimes adorn my drawings with a check mark, although I could never find out if she was mistaking them for school work or if she was actually a fan of my work expressing her approval in her own, teachery way.

Because of this obsession of mine with dinosaurs, I’ve come to learn quite a bit about them, meaning that I often find myself answering the questions of curious people about these mysterious creatures.

One of the most common questions I get is if I think dragons really existed one day. I suppose everyone wants me to say that dinosaurs and dragons are somehow the same thing, and so they are quite surprised when I answer starting with another question.

“Do you know what the word “dragon” means?” I ask. They usually say no, and then I explain that dragon comes from ancient Greek “drakon”, meaning “serpent” or “snake”. Indeed, dragons (at least in the Western world) were originally conceived as giant snakes, not as dinosaur-like, fire-breathing winged beasts.

In Greek myth we find plenty of stories involving these snake-like dragons. One of the most famous examples is Python. This particular dragon (some say there were actually two) lived in Mount Parnassus, where it was seemingly worshipped as a deity. There are several versions of this myth, but they all end the same way; the Olympian god Apollo takes over Mount Parnassus and slays Python with his arrows. He then has the serpent’s shrine replaced by his own. Due to the dragon’s divine nature, however, there were a series of rituals Apollo had to perform in order to keep Python’s spirit appeased.

Representations of Python always show him as a giant snake. Some historians, however, believe that the myth of Python must not be taken literally. Instead, they think the story is a metaphor for an ancient religious revolution; some even go as far as to saying that both Apollo and Python were originally humans--leaders of different religions or cults--and that the metaphor of the god slaying the dragon represents the triumph of one of said leaders over the other.

Personally, I believe that the story works just as fine when taken literally. It is possible that there was a dragon in Mount Parnassus, worshipped as a god in a shrine, tended by loyal priestesses. Snakes have been worshipped as gods in many cultures, and there’s plenty of evidence of a snake cult in Greece before the Olympian gods, so to speak, “came into power.” But of course, not just any snake can be a dragon.

My answer to those who ask me about dragons is always the same. “Yes, dragons did exist, and they still do exist. You have seen them in the zoo, and perhaps you even keep one as a pet”. Today, we call them “python snakes,” after the one that was worshipped in Mount Parnassus.

Photo by Parker Grice. Reticulated python provided by Twin Cities Reptiles.

Photo by Parker Grice. Reticulated python provided by Twin Cities Reptiles.That the mythical dragon slain by Apollo gave its name to some of the largest and most spectacular snakes today-- including the longest snake in the world, the reticulated python of South East Asia-- is no surprise. But people still are taken aback when I tell them my theory about pythons themselves being the inspiration for the myths of the Western dragons. Everyone wants dragons and dinosaurs to be the same!

The evidence for my hypothesis is plentiful, though. Greek and Roman historians, travelers and naturalists said once repeatedly that dragons were real, and that they were snakes of great size and might. Some of them were incredibly accurate in their descriptions. Most mentioned India and Ethiopia as the homelands of dragons; tropical Asia and Africa are indeed the home of the largest pythons. Even later in History, many authors describe python snakes calling them “dragons.”

Isidore of Seville said that dragons were the largest kind of serpent. St. John of Damascus said that “dragons do exist, but they are snakes born from other snakes… they are small when they are young, but then… they exceed all other serpents in length and are as thick as a huge log.” Perhaps most telling is the fact that instead of killing with venom (or fire), these original dragons killed by constriction- squeezing the life out of their prey with their powerful coils. Pliny the Elder said that dragons would battle with elephants, eventually constricting the poor pachyderms to death; but these titanic duels were also deadly for the dragon, Pliny said, for the elephant would collapse and crush its reptilian adversary under its weight.

Now, an elephant is way too big for a python to tackle, but the fact remains that the largest pythons do attack, constrict and devour pretty formidable prey; the remains of deer, sheep, wild boar, leopards and sun bears have all been recovered from the stomachs of reticulated pythons, for example. And once in a while, they’ve been known to kill humans too. It seems pretty evident to me that python snakes, ironically named after a dragon, were originally the inspiration for the dragon itself.

Native to warm countries, and often highly dependent on water, pythons would’ve been very difficult to transport and keep alive in Europe; but we do know that in Roman times, some of them were successfully kept and exhibited as curiosities in the Colosseum.

Is it possible, then, that some python snakes were captured earlier, either from Africa (there was a time in which African rock pythons were found in Egypt) or Asia and taken to Greece? In a country in which snakes were already considered sacred, it is not difficult to imagine a large python being kept as a living god in a shrine like that of Mount Parnassus. Interestingly, the shrine of Python was located over the Kerna spring waters, which flowed under the temple both keeping it warm and filling it, it is said, with strange fumes. Is it possible that these unique conditions created a sort of terrarium-like environment in the temple, allowing for the dragon to survive for many years and therefore attaining very large size?

Maybe someone did slay a dragon in Mount Parnassus. Maybe the bones of a large python snake will one day be found by archaeologists studying the site. Who knows?

Published on May 07, 2012 03:00

May 6, 2012

Feline Fury: Lion, Leopard, Lynx, Cheetahs

Some feline mayhem to report.

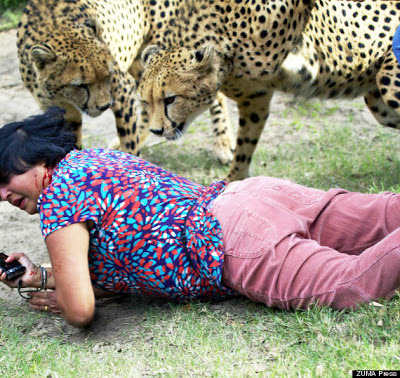

First, a cheetah petting gone horribly wrong:

Violet D'Mello mauled by 'tame' cheetahs at holiday safari park | Mail Online: "one of the beasts grabbed eight-year-old Camryn Malan, who was among other tourists in the enclosure, and began biting her leg.

Mrs D’Mello comforted the girl’s seven-year-old brother, Calum, telling him not to run so he would not aggravate the animals – but as she did so, the cheetahs turned on her.

The mother of two said: ‘I never imagined it would attack me because I was an adult. But the next thing I knew I was on the floor and the cheetah was right on top of me."

Her husband took photos while all this was going on, apparently not taking it seriously. My wife tells me I should, in case of a similar occurrence, abandon the camera and come to her rescue. (Thanks to Nik Nimbus for the news tip.)

Second, a leopard preferred not to be captured:

7 injured in leopard attack in Rajasthan, IBN Live News: "Seven persons, including some forest personnel, were injured when a leopard attacked them in Raghunathpura area in Chittoregarh district of Rajasthan, official sources said today. The incident took place yesterday when the animal attacked some villagers and forest personnel after they made an attempt to capture it, the officials said. The victims were admitted to a nearby hospital where their condition was stated to be stable"

Third, a pet lynx bit a woman on the arm:

NWCN.com Washington - Oregon - Idaho: ""There was a lynx cat - a pet that lived in the house and a girlfriend. The cat got jealous of the girlfriend, who was vacuuming, and it jumped on her and bit her," speculated Jenee Westbend, King County Animal Control officer.

Police and medics were called to the scene, but the lynx was still roaming inside the house. Medics waited outside until the lynx's owner came home and kenneled the cat."

I know I feel jealous of anybody who’s vacuuming.

Finally, video of a cute baby and a hungry lioness. I'm not sure I'd be as sanguine as this lady seems. (Thanks to Dan for the tip.)

Published on May 06, 2012 02:00