Gordon Grice's Blog, page 48

July 29, 2012

Fruit Flies Are Cannibals

Aka/Creative Commons

Interesting discovery about the common fruit fly, one of the most widely studied animals in the world, and one of its cousins. It seems there's always something new to see, even right under our noses.

Young Flies Cannibalize The Plump - Science News:

"In a feeding test, more than a third of the younger larvae survived by eating nothing but the older ones.

“I have never read or heard about this, and I was absolutely stunned that nobody has ever noticed this before,” said Thomas Flatt of the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna."

Thanks to Erin for the news tip.

Published on July 29, 2012 22:30

Giant Sturgeon Caught

Monster white sturgeon weighing 1,100 pounds caught in Canada:

"A monster white sturgeon weighing an estimated 1,100 pounds and measuring 12 feet, 4 inches was caught and released on the Fraser River.

This sturgeon is believed to be the biggest freshwater fish ever caught on rod and reel in North America...and possibly the oldest."

Related Post: Strange Creature from the Sea

Published on July 29, 2012 02:30

July 28, 2012

Video of Killer Whale Roughing Up Trainer

Parties not involved in the incident

Video shows SeaWorld trainer's underwater struggle with orca | Reuters:

"A newly released video shows a killer whale clamping down on a SeaWorld trainer's foot in 2006 and dragging him underwater, as he tries in vain to get back to the surface for air before the mammal finally sets him loose."

Thanks to Croconut for the news tip.

Related Post: Bimbo the Pilot Whale

Published on July 28, 2012 02:30

Video of Killer Whale Roughing Up Trainer

Parties not involved in the incident

Parties not involved in the incidentVideo shows SeaWorld trainer's underwater struggle with orca | Reuters:

"A newly released video shows a killer whale clamping down on a SeaWorld trainer's foot in 2006 and dragging him underwater, as he tries in vain to get back to the surface for air before the mammal finally sets him loose."

Thanks to Croconut for the news tip.

Related Post: Bimbo the Pilot Whale

Published on July 28, 2012 02:30

July 27, 2012

Animal Attack Movies: Eyes Without a Face

Eyes Without a Face (Georges Franju, 1960)

A horror movie about face transplants. It sounds pretty cheesy, but in fact it’s an understated, underplayed, beautifully photographed film. The genius is in the details: cars waiting at a train crossing, the sky gray, the pavement wet. The sound, unexplained for the moment, of dogs wailing when a man opens his garage door. The death of one of the malefactors, stabbed with a scalpel in the neck, between the strands of her pearl choker, which has been mentioned before because it hides her surgical scar. "Why?" she says as she sits down in the corner to die.

The dialog is full of authentic medical touches that lend credibility. In fact the film never seems incredible for a moment. What makes this truly impressive is that it precedes the first genuine face transplants by 45 years. Real-life recipients include people mauled by a bear, a chimpanzee, and, in the very first successful transplant, a dog—-which makes the movie’s combination of dog attack with face transplant weirdly topical.

Related Post: Dog Bites Off Woman's Face; Leeches Help Reattach It

Published on July 27, 2012 03:00

July 25, 2012

Electric Catfish, Part 2: Edison

James's Bengal cat, Aslan

James's Bengal cat, Aslanby guest writer James Smith

My second electric catfish, Edison, was doubtless purchased as part of an act of subconscious hostility towards one of my other pets. At least, that’s how it seemed later.

I had cut back on my fish-keeping—partly to have more room to devote to my major interest, reptiles and amphibians—although I did maintain a 30-gallon marine tank (the store where I worked, and still work, had just begun carrying saltwater fish and I wanted to be competent.) Marine fish are fascinating, beautiful and can, with proper selection and care, be hardy animals—if expensive. The hobby has come a long, long way from the old days. However, my marine endeavors were curtailed thanks to a very bored and highly predatory animal that shared my house—a domestic cat, specifically a Bengal named Aslan.

Bengals are gorgeous animals, deriving from a cross between a regular domestic cat and an Asian wildcat called the leopard cat (no relation to the leopard, apart from both being cats—leopard cats are around the size of a big domestic.) The more the wildcat blood is diluted, the smaller and more manageable the cat, as a rule: Aslan weighs about thirteen pounds, no bigger than a normal cat and smaller than my overweight female Maine Coon cross. Bengals do have a down side: they are very energetic and destructive when mood suits them; they have a distinct and very unpleasant yowl, best described as the sound a peacock might make while trying to impersonate an echolocating whale; and they have an incredible prey drive.

Aslan would spend hours leering in through the tank at my saltwater fish, and one day I arrived home to the inevitable: the cat, in my absence, had jumped up on the tank, and pawed open the hood, probably out of simple curiosity—he does the same thing with cabinet doors that don’t have a real latch. The fish, conditioned to rise when they sensed a tap up there signaling food, had come to the surface—where they were easy prey for the Bengal.

I swore off fish entirely for a while after that, but eventually I broke down and set up a 20-gallon long-style tank, and while musing about what to put in it, ran across a young electric catfish in a specialty aquarium store, again about six inches long. Given the sedentary habits and slow growth of the fish, I decided he would be fine in the tank I had for some time to come, and purchased him. As I say, I’m sure a psychologist would have a field day with the whys and wherefores here—they’d probably argue I had to know what was coming. All I can say is, I never consciously thought about the inevitable meeting until it happened.

This catfish, christened Edison, was a bit more outgoing than Galvani, perhaps due to being the only fish in his tank, and was out prowling about at all hours (I did not keep a light on in the tank, given the nocturnal behavior of its occupant.) I did give him live feeder fish from time to time, and he did appear to use his current to kill or stun them—the problem in ascertaining this was that as any aquarist knows, dumping a fish straight into a different tank can kill it from shock. So whether it was “death from shock” or “death from shocking” was open to question. When I gave him a baby crayfish about the size of a bee, however, Edison unmistakably made use of his current to subdue the crustacean.

Edison had initially simply tried to grab the crayfish in his jaws, but after receiving a pinch to the nose for his efforts, he retreated just beyond claw-range and seemed to almost be taking stock of the situation. The crayfish spun and pivoted wildly for several seconds while Edison hung back, and I could not help feeling a little sorry for it: it was clearly trying to keep its claws facing danger at all times, and in its efforts to deflect any fish that might be creeping up from behind, actually wound up doing the precise opposite every so often.

As with Galvani’s defensive strike, there was nothing to indicate that Edison had just released his weapon—no equivalent to a rattler’s S-coil or the dramatic handstand display of a skunk—except for the crayfish’s reaction: it flipped on its back, convulsed once, and lay still. Edison swam over, and, apparently satisfied of its death after cautious probing with his whiskers, set about ripping the crayfish into manageable chunks, shaking and worrying at it. It was like watching a bottom-dwelling shark—a nurse shark, say—in miniature, at work on a lobster.

In the course of tank maintenance, Edison managed to zap me a couple of times, something Galvani had never done—of course, Galvani had more room to maneuver out of the way in the 75. I’m uncertain just how high he had the juice turned up, because while it was startling and certainly unpleasant—rather like a very bad doorknob shock from discharging static electricity—it was less painful than assorted stings and bites I’ve suffered at various times over my checkered career. Granted, he was a small fish. But I have an idea things could have been much worse had he felt truly threatened, because one day, the epic confrontation of Cat vs. Catfish finally occurred.

Aslan, who had been on model behavior for over a month, finally succumbed to his baser urges and decided to send Edison the same way as he had the saltwater fish. I was sitting in my easy chair, multi-tasking—watching a movie, reading and having a snack—when I heard the telltale thump of the cat landing atop the tank and the sound of him pawing at the lid, then the splash of his paw in the water. I was getting up to shoo the cat off the tank when Edison saved me the trouble. Aslan let out an unholy screech and shot into the air with all four feet. He came down bristling, arching and spitting like a witch’s Halloween cat, snarling and shaking his head as he bounded out of the room. From that time on, Aslan studiously avoided Edison’s tank, to the point of not even resting on top of it as he frequently did—and still does—with some of my reptile cages.

Edison died unexpectedly about two years ago—I was home one night when I heard the splash of a jumping fish, and turned to see him flapping and gasping on the floor. Scooping him up with a piece of cardboard and dumping him back into the tank, I watched as he settled to the bottom. I had seen fish survive jumping from tanks before and assumed he would recover. Unfortunately, he must have fallen in just the right way to damage something internally, and within a day or two, he was dead. Since the electric charge of a dead fish can still fire by reflex until decay causes the organ to break down, I netted him out somewhat gingerly. After placing him in a small wooden box, I took him down to the garden—where most of the family’s pets have ended up after shuffling off this mortal coil—and interred him next to the horseradish. Somehow such a remarkable fish deserved more than “burial at sea” or simply being tossed over the neighbors’ bank for the crows or resident fox to clean up.

Edison’s tank is now inhabited by a Ruthven’s kingsnake, and I currently have no fish. But it’s only a matter of time and circumstance before I set up another tank—and I have more than half an idea that if I only find space and time for one aquarium, with one fish in it, that fish will be an electric catfish.

Published on July 25, 2012 22:00

Electric Catfish, Part 1: Galvani

Stan Shebs/Creative Commons

by guest writer James Smith

My taste in pets has been characterized by various friends and family

members as being “exotic,” “eclectic” and “just plain weird,” and I must admit

that there may be something to their claims. Perhaps no animal better

exemplifies the point than one of my favorite fish, an unprepossessing species

from western and central Africa. Sluggish and dull-colored, perhaps best

imagined as a finned sausage with two tiny, though functional, eyes and six

whiskers at one end, it does not strike one at first glance as an exciting or

dynamic aquarium inhabitant. In fact, one might be forgiven for wondering if it

is even alive when glimpsed by day, resting on the bottom beneath a cave or

driftwood.

The fish in question is the electric catfish—technically, there are two

genera of electric cats, one made up of large species reaching nearly three

feet in length and the other one of dwarf species under a foot long, totaling

some twenty-odd varieties. Only a couple really appear in the aquarium trade

with any regularity. As the name implies, these fish can generate a powerful

electric charge by means of an organ made up of modified muscle cells, spanning

the length of the body. A fairish number of fish possess some form of

electrical organ, but in most of these fish, the organ is “weakly

electrical”—that is, it is only useful for orientation, communicating with

others of the same species, and detection of prey: given the small eyes,

nocturnal habits and murky habitat of most electric fish, it is as vital to

their existence as are their gills or fins. However, the electric cats—like a

handful of other species, most notably the electric eel—is a “strongly

electrical” species: that is, it produces a fairly powerful current—a

modest-sized 20-incher can unleash up to 350 volts, though thankfully at a

relatively low amperage—which can be used to stun or kill prey, or conversely,

in the fish’s own defense against an attacker.

Electric catfish in the wild have been recorded at lengths approaching

four feet and a whopping 44 pounds, although in aquaria this size is rarely

attained and 20 inches is more likely the upper limit. Growth is not very rapid,

or at least, does not seem to occur at anything like the headlong rate of, say,

some of the larger cichlids. This suggests that these animals enjoy a long

lifespan, even by the standards of large fish—and plenty of the bigger aquarium

fish will comfortably outlive a large dog under ideal conditions.

My first electric cat, Galvani, was the mild-mannered but tough guy in

a tank full of decidedly antisocial finned hoodlums. At the time I was running

a 75-gallon tank where I would toss any fish that became too obnoxious and

nasty for my 38 and 55-gallon jobs. I did notice that every so often, perfectly

healthy and aggressive fish would go, literally overnight, into a sudden

decline spanning the course of a few days, swimming erratically, being unable

to stabilize in the water, and eventually dying, but I could not find anything

to suggest disease or parasites. It was not until I observed Galvani’s

encounter with a clown knifefish named Rajah—a large, predatory Asian species,

which like the electric cat, can attain lengths of over three feet in nature,

but averages about half that in aquaria—that I began to realize what had been

happening.

Galvani was only about six inches long, while Rajah was easily twice

that. While not big enough to swallow such a large meal, Rajah would attack and

beat up fish far too big to eat, and he ruled the tank. Even my nastiest

cichlids—red devils—feared him. So far, Rajah had left the catfish alone, but

this particular evening, he spotted Galvani leaving his cave to munch up a

juicy nightcrawler I had dropped on the bottom, and took action, arrowing

towards the catfish with open jaws. There was, of course, no blinding flash, no

crackling sound, but Galvani clearly unleashed his charge as Rajah was closing

with millimeters to spare. The big knifefish stiffened and nosedived into a

cluster of fake plants, gills pumping furiously. Galvani turned and wriggled

back into his cave, dragging the earthworm, which he had not dropped during the

whole episode. After some time, Rajah hauled himself groggily up into the water

column, and more or less returned to normal by morning. He did, however, give

Galvani a wide berth from then on.

As with venomous snakes, an electric fish has some discretion over the

amount of voltage it unleashes, and would probably as soon not have to waste

energy on something it cannot eat, so a defensive shock is designed to

discourage, not necessarily kill, an attacker. Because Galvani ate pellets and

the occasional earthworm or piece of frozen fish, I never saw him use his

extraordinary weapon for killing prey. But I suspect that the fish who

mysteriously died—all of them cichlids of one sort or another, and all young

specimens around four or five inches—had received a defensive shock from

Galvani and were simply not sturdy enough to withstand it, dying of stress or

perhaps even some internal injury.

When I dismantled the tank, Galvani was still going strong and at last

report, is still alive—when I last saw him he was perhaps fifteen inches long. If

he has a lifespan comparable to some other big, slow-growing fish, he will be

around for a long, long time to come.

Published on July 25, 2012 02:30

Electric Catfish, Part 1: Galvani

Stan Shebs/Creative Commons

Stan Shebs/Creative Commonsby guest writer James Smith

My taste in pets has been characterized by various friends and family members as being “exotic,” “eclectic” and “just plain weird,” and I must admit that there may be something to their claims. Perhaps no animal better exemplifies the point than one of my favorite fish, an unprepossessing species from western and central Africa. Sluggish and dull-colored, perhaps best imagined as a finned sausage with two tiny, though functional, eyes and six whiskers at one end, it does not strike one at first glance as an exciting or dynamic aquarium inhabitant. In fact, one might be forgiven for wondering if it is even alive when glimpsed by day, resting on the bottom beneath a cave or driftwood.

The fish in question is the electric catfish—technically, there are two genera of electric cats, one made up of large species reaching nearly three feet in length and the other one of dwarf species under a foot long, totaling some twenty-odd varieties. Only a couple really appear in the aquarium trade with any regularity. As the name implies, these fish can generate a powerful electric charge by means of an organ made up of modified muscle cells, spanning the length of the body. A fairish number of fish possess some form of electrical organ, but in most of these fish, the organ is “weakly electrical”—that is, it is only useful for orientation, communicating with others of the same species, and detection of prey: given the small eyes, nocturnal habits and murky habitat of most electric fish, it is as vital to their existence as are their gills or fins. However, the electric cats—like a handful of other species, most notably the electric eel—is a “strongly electrical” species: that is, it produces a fairly powerful current—a modest-sized 20-incher can unleash up to 350 volts, though thankfully at a relatively low amperage—which can be used to stun or kill prey, or conversely, in the fish’s own defense against an attacker.

Electric catfish in the wild have been recorded at lengths approaching four feet and a whopping 44 pounds, although in aquaria this size is rarely attained and 20 inches is more likely the upper limit. Growth is not very rapid, or at least, does not seem to occur at anything like the headlong rate of, say, some of the larger cichlids. This suggests that these animals enjoy a long lifespan, even by the standards of large fish—and plenty of the bigger aquarium fish will comfortably outlive a large dog under ideal conditions.

My first electric cat, Galvani, was the mild-mannered but tough guy in a tank full of decidedly antisocial finned hoodlums. At the time I was running a 75-gallon tank where I would toss any fish that became too obnoxious and nasty for my 38 and 55-gallon jobs. I did notice that every so often, perfectly healthy and aggressive fish would go, literally overnight, into a sudden decline spanning the course of a few days, swimming erratically, being unable to stabilize in the water, and eventually dying, but I could not find anything to suggest disease or parasites. It was not until I observed Galvani’s encounter with a clown knifefish named Rajah—a large, predatory Asian species, which like the electric cat, can attain lengths of over three feet in nature, but averages about half that in aquaria—that I began to realize what had been happening.

Galvani was only about six inches long, while Rajah was easily twice that. While not big enough to swallow such a large meal, Rajah would attack and beat up fish far too big to eat, and he ruled the tank. Even my nastiest cichlids—red devils—feared him. So far, Rajah had left the catfish alone, but this particular evening, he spotted Galvani leaving his cave to munch up a juicy nightcrawler I had dropped on the bottom, and took action, arrowing towards the catfish with open jaws. There was, of course, no blinding flash, no crackling sound, but Galvani clearly unleashed his charge as Rajah was closing with millimeters to spare. The big knifefish stiffened and nosedived into a cluster of fake plants, gills pumping furiously. Galvani turned and wriggled back into his cave, dragging the earthworm, which he had not dropped during the whole episode. After some time, Rajah hauled himself groggily up into the water column, and more or less returned to normal by morning. He did, however, give Galvani a wide berth from then on.

As with venomous snakes, an electric fish has some discretion over the amount of voltage it unleashes, and would probably as soon not have to waste energy on something it cannot eat, so a defensive shock is designed to discourage, not necessarily kill, an attacker. Because Galvani ate pellets and the occasional earthworm or piece of frozen fish, I never saw him use his extraordinary weapon for killing prey. But I suspect that the fish who mysteriously died—all of them cichlids of one sort or another, and all young specimens around four or five inches—had received a defensive shock from Galvani and were simply not sturdy enough to withstand it, dying of stress or perhaps even some internal injury.

When I dismantled the tank, Galvani was still going strong and at last report, is still alive—when I last saw him he was perhaps fifteen inches long. If he has a lifespan comparable to some other big, slow-growing fish, he will be around for a long, long time to come.

Published on July 25, 2012 02:30

July 24, 2012

Opossums Immune to Poisons

Piccolo Namek/Creative Commons

This fascinating (and entertaining) article explains how Virginia opossums were found to be immune to many venoms, including those produced by cobras and other animals they never encounter, as well as toxins like ricin. Scientists have isolated the toxin-killing agent in the possum and hope to turn it into a universal antidote humans can use. They've already proved it can confer immunity on rats.

This fascinating (and entertaining) article explains how Virginia opossums were found to be immune to many venoms, including those produced by cobras and other animals they never encounter, as well as toxins like ricin. Scientists have isolated the toxin-killing agent in the possum and hope to turn it into a universal antidote humans can use. They've already proved it can confer immunity on rats.

What are Opossums? ‹ Bittel Me This:

"We’re talking timber rattlers, cottonmouths, Russell’s vipers and common Asiatic cobras. We know this because scientists rounded up a bunch of nasties and forced them to bite a bunch of unfortunate opossums, the latter of which responded like it was a mild bee sting. "

Published on July 24, 2012 02:42

July 23, 2012

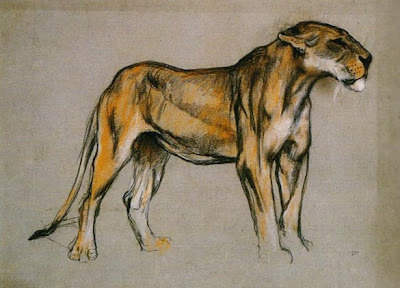

Lioness vs. Farmer

Looks like a case of an animal protecting her cub:

Zimbabwe Lion Attacks Local Farmer, Joel Ngwenya:

""The lioness looked straight into my eyes, staring and roaring," Ngwenya told the paper from a hospital.

It pinned him down with its claws and continued staring at him "face to face," he said. The lioness briefly moved away toward a lion cub then turned back on him."

Published on July 23, 2012 03:00