Gordon Grice's Blog, page 38

November 25, 2012

Zoo Lions

Published on November 25, 2012 01:00

November 22, 2012

Wildlife Classics: Bhoota's Last Shikar (A Lion Hunt)

by JH Patterson

from Man-Eaters of Tsavo (1907)

I lay awake listening to roar answering roar in every direction

round our camp, and realised that we were indeed in the midst of a favourite

haunt of the king of beasts. It is one thing to hear a lion in captivity, when

one knows he is safe behind iron bars; but quite another to listen to him when he

is ramping around in the vicinity of one's fragile tent, which with a single

blow he could tear to pieces. Still, all this roaring was of good omen for the

next day's sport.

According to our over-night arrangement, we were up betimes

in the morning, but as there was a great deal of work to be done before we

could get away, it was quite midday

before we made ready to start. I ought to mention before going further that as

a rule Spooner declined my company on shooting trips, as he was convinced that

I should get "scuppered" sooner or later if I persisted in going

after lions with a "popgun," as he contemptuously termed my .303.

Indeed, this was rather a bone of contention between us, he being a firm

believer (and rightly) in a heavy weapon for big and dangerous game, while I always

did my best to defend the .303 which I was in the habit of using. On this

occasion we effected a compromise for the day, I accepting the loan of his

spare 12-bore rifle as a second gun in case I should get to close quarters. But

my experience has been that it is always a very dangerous thing to rely on a

borrowed gun or rifle, unless it has precisely the same action as one's own;

and certainly in this instance it almost proved disastrous.

Having thus seen to our rifles and ammunition and taken care

also that some brandy was put in the luncheon-basket in case of an accident, we

set off early in the afternoon in Spooner's tonga, which is a two-wheeled cart

with a hood over it. The party consisted of Spooner and myself, Spooner's

Indian shikari Bhoota, my own gun-boy Mahina, and two other Indians, one of

whom, Imam Din, rode in the tonga,

while the other led a spare horse called "Blazeaway." Now it may seem

a strange plan to go lion-hunting in a tonga, but there is no better way

of getting about country like the Athi Plains, where -- so long as it is dry --

there is little or nothing to obstruct wheeled traffic. Once started, we

rattled over the smooth expanse at a good rate, and on the way bagged a hartebeeste

and a couple of gazelle, as fresh meat was badly needed in camp; besides, they

offered most tempting shots, for they stood stock-still gazing at us, struck no

doubt by the novel appearance of our conveyance. Next we came upon a herd of

wildebeeste, and here we allowed Bhoota, who was a wary shikari and an old

servant of Spooner's, to stalk a solitary bull. He was highly pleased at this

favour, and did the job admirably.

At last we reached the spot where I had seen the two lions

on the previous day -- a slight hollow, covered with long grass; but there was now

no trace of them to be discovered, so we moved further on and had another good

beat round. After some little time the excitement began by our spying the

black-tipped ears of a lioness projecting above the grass, and the next moment

a very fine lion arose from beside her and gave us a full view of his grand

head and mane. After staring fixedly at us in an inquiring sort of way as we

slowly advanced upon them, they both turned and slowly trotted off, the lion stopping

every now and again to gaze round in our direction. Very imposing and majestic

he looked, too, as he thus turned his great shaggy head defiantly towards us,

and Spooner had to admit that it was the finest sight he had ever seen. For a

while we followed them on foot; but finding at length that they were getting

away from us and would soon be lost to sight over a bit of rising ground, we

jumped quickly into the tonga and galloped round the base of the knoll so as to

cut off their retreat, the excitement of the rough and bumpy ride being

intensified a hundred-fold by the probability of our driving slap into the pair

on rounding the rise. On getting to the other side, however, they were nowhere

to be seen, so we drove on as hard as we could to the top, whence we caught

sight of them about four hundred yards away. As there seemed to be no prospect

of getting nearer we decided to open fire at this range, and at the third shot

the lioness tumbled over to my .303. At first I thought I had done for her, as

for a few minutes she lay on the ground kicking and struggling; but in the end,

although evidently badly hit, she rose to her feet and followed the lion, who

had escaped uninjured, into some long grass from which we could not hope to

dislodge them.

As it was now late in the afternoon, and as there seemed no

possibility of inducing the lions to leave the thicket in which they had

concealed themselves, we turned back towards camp, intending to come out again

the next day to track the wounded lioness. I was now riding

"Blazeaway" and was trotting along in advance of the tonga, when

suddenly he shied badly at a hyena, which sprang up out of the grass almost

from beneath his feet and quickly scampered off. I pulled up for a moment and

sat watching the hyena's ungainly bounds, wondering whether he were worth a

shot. Suddenly I felt "Blazeaway" trembling violently beneath me, and

on looking over my left shoulder to discover the reason, I was startled to see

two fine lions not more than a hundred yards away, evidently the pair which I

had seen the day before and which we had really come in search of. They looked as

if they meant to dispute our passage, for they came slowly towards me for about

ten yards or so and then lay down, watching me steadily all the time. I called

out to Spooner, "Here are the lions I told you about," and he whipped

up the ponies and in a moment or two was beside me with the tonga.

By this time I had seized my .303 and dismounted, so we at

once commenced a cautious advance on the crouching lions, the arrangement being

that Spooner was to take the right-hand one and I the other. We had got to

within sixty yards' range without incident and were just about to sit down

comfortably to "pot" them, when they suddenly surprised us by turning

and bolting off. I managed, however, to put a bullet into the one I had marked

just as he crested a bank, and he looked very grand as he reared up against the

sky and clawed the air on feeling the lead. For a second or two he gave me the

impression that he was about to charge; but luckily he changed his mind and

followed his companion, who had so far escaped scot free. I immediately mounted

"Blazeaway" and galloped off in hot pursuit, and after about half a

mile of very stiff going got up with them once more. Finding now that they

could not get away, they halted; came to bay and then charged down upon me, the

wounded lion leading. I had left my rifle behind, so all I could do was to turn

and fly as fast as "Blazeaway" could go, praying inwardly the while

that he would not put his foot into a hole. When the lions saw that they were

unable to overtake me, they gave up the chase and lay down again, the wounded

one being about two hundred yards in front of the other. At once I pulled up

too, and then went back a little way, keeping a careful eye upon them; and I

continued these tactics of riding up and down at a respectful distance until

Spooner came up with the rifles, when we renewed the attack.

As a first measure I thought it advisable to disable the

unhurt lion if possible, and, still using the .303, I got him with the second

shot at a range of about three hundred yards. He seemed badly hit, for he

sprang into the air and apparently fell heavily. I then exchanged my .303 for

Spooner's spare 12-bore rifle, and we turned our attention to the nearer lion,

who all this time had been lying perfectly still, watching our movements closely,

and evidently just waiting to be down upon us the moment we came within

charging distance. He was never given this opportunity, however, for we did not

approach nearer than ninety yards, when Spooner sat down comfortably and

knocked him over quite dead with one shot from his .577, the bullet entering

the left shoulder obliquely and passing through the heart.

It was now dusk, and there was no time to be lost if we

meant to bag the second lion as well. We therefore resumed our cautious

advance, moving to the right, as we went, so as to get behind us what light

there was remaining. The lion of course twisted round in the grass in such a

way as always to keep facing us, and looked very ferocious, so that I was

convinced that unless he were entirely disabled by the first shot he would be

down on us like a whirlwind. All the same, I felt confident that, even in this

event, one of us would succeed in stopping him before he could do any damage;

but in this I was unfortunately to be proved mistaken.

Eventually we managed to get within eighty yards of the

enraged animal, I being about five yards to the left front of Spooner, who was followed

by Bhoota at about the same distance to his right rear. By this time the lion

was beside himself with fury, growling savagely and raising quite a cloud of

dust by lashing his tail against the ground. It was clearly high time that we did

something, so asking Spooner to fire, dropped on one knee and waited. Nor was I

kept long in suspense, for the moment Spooner's shot rang out, up jumped the

lion and charged down in a bee-line for me, coming in long, low bounds at great

speed. I fired the right barrel at about fifty yards, but apparently missed;

the left at about half that range, still without stopping effect. I knew then

that there was no time reload, so remained kneeling, expecting him to be on me

the next moment. Suddenly, just as he was within a bound of me, he made a quick

turn, to my right. "Good heavens," I thought, "he is going for

Spooner." I was wrong in this, however, for like a flash he passed Spooner

also, and with a last tremendous bound seized Bhoota by the leg and rolled over

and over with him for some yards in the impetus of the rush. Finally he stood

over him and tried to seize him by the throat, which the brave fellow prevented

by courageously stuffing his left arm right into the great jaws. Poor Bhoota!

By moving at the critical moment, he had diverted the lion's attention from me

and had drawn the whole fury of the charge on to himself.

All this, of course, happened in only a second or two. In

the short instant that intervened, I felt a cartridge thrust into my hand by

Spooner's plucky servant, Imam Din, who had carried the 12-bore all day and who

had stuck to me gallantly throughout the charge; and shoving it in, I rushed as

quickly as I could to Bhoota's rescue. Meanwhile, Spooner had got there before

me and when I came up actually had his left hand on the lion's flank, in a vain

attempt to push him off Bhoota's prostrate body and so get at the heavy rifle which

the poor fellow still stoutly clutched. The lion, however, was so busily

engaged mauling Bhoota's arm that he paid not the slightest attention to

Spooner's efforts. Unfortunately, as he was facing straight in my direction, I

had to move up in full view of him, and the moment I reached his head, he

stopped chewing the arm, though still holding it in his mouth, and threw

himself back on his haunches, preparing for a spring, at the same time curling

back his lips and exposing his long tusks in a savage snarl. I knew then that I

had not a moment to spare, so I threw the rifle up to my shoulder and pulled the

trigger. Imagine my utter despair and horror when it did not go off!

"Misfire again," I thought, and my heart almost stopped beating. As took

a step backwards, I felt it was all over no for he would never give me time to

extract the cartridge and load again. Still I took another step backwards,

keeping my eyes fixed on the lion's, which were blazing with rage; and in the middle

of my third step, just as the brute was gathering himself for his spring, it

suddenly struck me that in my haste and excitement, I had forgotten that I was

using a borrowed rifle and had not pulled back the hammer (my own was hammerless).

To do this and put a bullet through the lion's brain was then the work of a

moment; and he fell dead instantly right on the top of Bhoota.

We did not lose a moment in rolling his great carcase off

Bhoota's body and quickly forced opening the jaws so as to disengage the

mangled arm which still remained in his mouth. By this time the poor shikari

was in a fainting condition, and we flew to the tonga for the brandy flask which we

had so providentially brought with us. On making a rough examination of the

wounded man, we found that his left arm and right leg were both frightfully

mauled, the latter being broken as well. He was lifted tenderly into the tonga -- how thankful

we now were to have it with us! -- and Spooner at once set off with him to camp

and the doctor.

Before following them home I made a hasty examination of the

dead lion and found him to be a very good specimen in every way. I was particularly

satisfied to see that one of the two shots I had fired as he charged down upon

me had taken effect. The bullet had entered below the right eye, and only just

missed the brain. Unfortunately it was a steel one which Spooner had unluckily

brought in his ammunition bag by mistake; still one would have thought that a shot

of this kind, even with a hard bullet, would at least have checked the lion for

the moment. As a matter of fact, however, it went clean through him without

having the slightest stopping effect. My last bullet, which was of soft lead, had

entered close to the right eye and embedded itself in the brain. By this time

it had grown almost dark, so I left the two dead lions where they lay and rode

for camp, which I was lucky enough to reach without further adventure or mishap.

I may mention here that early next morning two other lions were found devouring

the one we had first shot; but they had not had time to do much damage, and the

head, which I have had mounted, makes a very fine trophy indeed. The lion that

mauled Bhoota was untouched.

On my arrival in camp I found that everything that was

possible was being done for poor Bhoota by Dr. McCulloch, the same who had

travelled up with me to Tsavo and shot the ostrich from the train on my first

arrival in the country, and who was luckily on the spot. His wounds had been

skilfully dressed, the broken leg put in splints, and under the influence of a

soothing draught the poor fellow was soon sleeping peacefully. At first we had

great hope of saving both life and limb, and certainly for some days he seemed

to be getting on as well as could be expected. The wounds, however, were very bad

ones, especially those on the leg where the long tusks had met through and

through the flesh, leaving over a dozen deep tooth marks; the arm, though

dreadfully mauled, soon healed. It was wonderful to notice how cheerfully the

old shikari, bore it all, and a pleasure to listen to his tale of how he would

have his revenge on the whole tribe of lions as soon as he was able to get

about again. But alas, his shikar was over. The leg got rapidly worse, and

mortification setting in, it had to be amputated half way up the thigh.

Dr. Winston Waters performed the operation most skilfully,

and curiously enough the operating table was canopied with the skin of the lion

which had been responsible for the injury. Bhoota made a good recovery from the

operation, but seemed to lose heart when he found that he had only one leg

left, as according to his ideas he had now but a poor chance of being allowed

to enter Heaven. We did all that was possible for him, and Spooner especially

could not have looked after a brother more tenderly; but to our great sorrow he

sank gradually, and died on July 19.

from Man-Eaters of Tsavo (1907)

I lay awake listening to roar answering roar in every direction

round our camp, and realised that we were indeed in the midst of a favourite

haunt of the king of beasts. It is one thing to hear a lion in captivity, when

one knows he is safe behind iron bars; but quite another to listen to him when he

is ramping around in the vicinity of one's fragile tent, which with a single

blow he could tear to pieces. Still, all this roaring was of good omen for the

next day's sport.

According to our over-night arrangement, we were up betimes

in the morning, but as there was a great deal of work to be done before we

could get away, it was quite midday

before we made ready to start. I ought to mention before going further that as

a rule Spooner declined my company on shooting trips, as he was convinced that

I should get "scuppered" sooner or later if I persisted in going

after lions with a "popgun," as he contemptuously termed my .303.

Indeed, this was rather a bone of contention between us, he being a firm

believer (and rightly) in a heavy weapon for big and dangerous game, while I always

did my best to defend the .303 which I was in the habit of using. On this

occasion we effected a compromise for the day, I accepting the loan of his

spare 12-bore rifle as a second gun in case I should get to close quarters. But

my experience has been that it is always a very dangerous thing to rely on a

borrowed gun or rifle, unless it has precisely the same action as one's own;

and certainly in this instance it almost proved disastrous.

Having thus seen to our rifles and ammunition and taken care

also that some brandy was put in the luncheon-basket in case of an accident, we

set off early in the afternoon in Spooner's tonga, which is a two-wheeled cart

with a hood over it. The party consisted of Spooner and myself, Spooner's

Indian shikari Bhoota, my own gun-boy Mahina, and two other Indians, one of

whom, Imam Din, rode in the tonga,

while the other led a spare horse called "Blazeaway." Now it may seem

a strange plan to go lion-hunting in a tonga, but there is no better way

of getting about country like the Athi Plains, where -- so long as it is dry --

there is little or nothing to obstruct wheeled traffic. Once started, we

rattled over the smooth expanse at a good rate, and on the way bagged a hartebeeste

and a couple of gazelle, as fresh meat was badly needed in camp; besides, they

offered most tempting shots, for they stood stock-still gazing at us, struck no

doubt by the novel appearance of our conveyance. Next we came upon a herd of

wildebeeste, and here we allowed Bhoota, who was a wary shikari and an old

servant of Spooner's, to stalk a solitary bull. He was highly pleased at this

favour, and did the job admirably.

At last we reached the spot where I had seen the two lions

on the previous day -- a slight hollow, covered with long grass; but there was now

no trace of them to be discovered, so we moved further on and had another good

beat round. After some little time the excitement began by our spying the

black-tipped ears of a lioness projecting above the grass, and the next moment

a very fine lion arose from beside her and gave us a full view of his grand

head and mane. After staring fixedly at us in an inquiring sort of way as we

slowly advanced upon them, they both turned and slowly trotted off, the lion stopping

every now and again to gaze round in our direction. Very imposing and majestic

he looked, too, as he thus turned his great shaggy head defiantly towards us,

and Spooner had to admit that it was the finest sight he had ever seen. For a

while we followed them on foot; but finding at length that they were getting

away from us and would soon be lost to sight over a bit of rising ground, we

jumped quickly into the tonga and galloped round the base of the knoll so as to

cut off their retreat, the excitement of the rough and bumpy ride being

intensified a hundred-fold by the probability of our driving slap into the pair

on rounding the rise. On getting to the other side, however, they were nowhere

to be seen, so we drove on as hard as we could to the top, whence we caught

sight of them about four hundred yards away. As there seemed to be no prospect

of getting nearer we decided to open fire at this range, and at the third shot

the lioness tumbled over to my .303. At first I thought I had done for her, as

for a few minutes she lay on the ground kicking and struggling; but in the end,

although evidently badly hit, she rose to her feet and followed the lion, who

had escaped uninjured, into some long grass from which we could not hope to

dislodge them.

As it was now late in the afternoon, and as there seemed no

possibility of inducing the lions to leave the thicket in which they had

concealed themselves, we turned back towards camp, intending to come out again

the next day to track the wounded lioness. I was now riding

"Blazeaway" and was trotting along in advance of the tonga, when

suddenly he shied badly at a hyena, which sprang up out of the grass almost

from beneath his feet and quickly scampered off. I pulled up for a moment and

sat watching the hyena's ungainly bounds, wondering whether he were worth a

shot. Suddenly I felt "Blazeaway" trembling violently beneath me, and

on looking over my left shoulder to discover the reason, I was startled to see

two fine lions not more than a hundred yards away, evidently the pair which I

had seen the day before and which we had really come in search of. They looked as

if they meant to dispute our passage, for they came slowly towards me for about

ten yards or so and then lay down, watching me steadily all the time. I called

out to Spooner, "Here are the lions I told you about," and he whipped

up the ponies and in a moment or two was beside me with the tonga.

By this time I had seized my .303 and dismounted, so we at

once commenced a cautious advance on the crouching lions, the arrangement being

that Spooner was to take the right-hand one and I the other. We had got to

within sixty yards' range without incident and were just about to sit down

comfortably to "pot" them, when they suddenly surprised us by turning

and bolting off. I managed, however, to put a bullet into the one I had marked

just as he crested a bank, and he looked very grand as he reared up against the

sky and clawed the air on feeling the lead. For a second or two he gave me the

impression that he was about to charge; but luckily he changed his mind and

followed his companion, who had so far escaped scot free. I immediately mounted

"Blazeaway" and galloped off in hot pursuit, and after about half a

mile of very stiff going got up with them once more. Finding now that they

could not get away, they halted; came to bay and then charged down upon me, the

wounded lion leading. I had left my rifle behind, so all I could do was to turn

and fly as fast as "Blazeaway" could go, praying inwardly the while

that he would not put his foot into a hole. When the lions saw that they were

unable to overtake me, they gave up the chase and lay down again, the wounded

one being about two hundred yards in front of the other. At once I pulled up

too, and then went back a little way, keeping a careful eye upon them; and I

continued these tactics of riding up and down at a respectful distance until

Spooner came up with the rifles, when we renewed the attack.

As a first measure I thought it advisable to disable the

unhurt lion if possible, and, still using the .303, I got him with the second

shot at a range of about three hundred yards. He seemed badly hit, for he

sprang into the air and apparently fell heavily. I then exchanged my .303 for

Spooner's spare 12-bore rifle, and we turned our attention to the nearer lion,

who all this time had been lying perfectly still, watching our movements closely,

and evidently just waiting to be down upon us the moment we came within

charging distance. He was never given this opportunity, however, for we did not

approach nearer than ninety yards, when Spooner sat down comfortably and

knocked him over quite dead with one shot from his .577, the bullet entering

the left shoulder obliquely and passing through the heart.

It was now dusk, and there was no time to be lost if we

meant to bag the second lion as well. We therefore resumed our cautious

advance, moving to the right, as we went, so as to get behind us what light

there was remaining. The lion of course twisted round in the grass in such a

way as always to keep facing us, and looked very ferocious, so that I was

convinced that unless he were entirely disabled by the first shot he would be

down on us like a whirlwind. All the same, I felt confident that, even in this

event, one of us would succeed in stopping him before he could do any damage;

but in this I was unfortunately to be proved mistaken.

Eventually we managed to get within eighty yards of the

enraged animal, I being about five yards to the left front of Spooner, who was followed

by Bhoota at about the same distance to his right rear. By this time the lion

was beside himself with fury, growling savagely and raising quite a cloud of

dust by lashing his tail against the ground. It was clearly high time that we did

something, so asking Spooner to fire, dropped on one knee and waited. Nor was I

kept long in suspense, for the moment Spooner's shot rang out, up jumped the

lion and charged down in a bee-line for me, coming in long, low bounds at great

speed. I fired the right barrel at about fifty yards, but apparently missed;

the left at about half that range, still without stopping effect. I knew then

that there was no time reload, so remained kneeling, expecting him to be on me

the next moment. Suddenly, just as he was within a bound of me, he made a quick

turn, to my right. "Good heavens," I thought, "he is going for

Spooner." I was wrong in this, however, for like a flash he passed Spooner

also, and with a last tremendous bound seized Bhoota by the leg and rolled over

and over with him for some yards in the impetus of the rush. Finally he stood

over him and tried to seize him by the throat, which the brave fellow prevented

by courageously stuffing his left arm right into the great jaws. Poor Bhoota!

By moving at the critical moment, he had diverted the lion's attention from me

and had drawn the whole fury of the charge on to himself.

All this, of course, happened in only a second or two. In

the short instant that intervened, I felt a cartridge thrust into my hand by

Spooner's plucky servant, Imam Din, who had carried the 12-bore all day and who

had stuck to me gallantly throughout the charge; and shoving it in, I rushed as

quickly as I could to Bhoota's rescue. Meanwhile, Spooner had got there before

me and when I came up actually had his left hand on the lion's flank, in a vain

attempt to push him off Bhoota's prostrate body and so get at the heavy rifle which

the poor fellow still stoutly clutched. The lion, however, was so busily

engaged mauling Bhoota's arm that he paid not the slightest attention to

Spooner's efforts. Unfortunately, as he was facing straight in my direction, I

had to move up in full view of him, and the moment I reached his head, he

stopped chewing the arm, though still holding it in his mouth, and threw

himself back on his haunches, preparing for a spring, at the same time curling

back his lips and exposing his long tusks in a savage snarl. I knew then that I

had not a moment to spare, so I threw the rifle up to my shoulder and pulled the

trigger. Imagine my utter despair and horror when it did not go off!

"Misfire again," I thought, and my heart almost stopped beating. As took

a step backwards, I felt it was all over no for he would never give me time to

extract the cartridge and load again. Still I took another step backwards,

keeping my eyes fixed on the lion's, which were blazing with rage; and in the middle

of my third step, just as the brute was gathering himself for his spring, it

suddenly struck me that in my haste and excitement, I had forgotten that I was

using a borrowed rifle and had not pulled back the hammer (my own was hammerless).

To do this and put a bullet through the lion's brain was then the work of a

moment; and he fell dead instantly right on the top of Bhoota.

We did not lose a moment in rolling his great carcase off

Bhoota's body and quickly forced opening the jaws so as to disengage the

mangled arm which still remained in his mouth. By this time the poor shikari

was in a fainting condition, and we flew to the tonga for the brandy flask which we

had so providentially brought with us. On making a rough examination of the

wounded man, we found that his left arm and right leg were both frightfully

mauled, the latter being broken as well. He was lifted tenderly into the tonga -- how thankful

we now were to have it with us! -- and Spooner at once set off with him to camp

and the doctor.

Before following them home I made a hasty examination of the

dead lion and found him to be a very good specimen in every way. I was particularly

satisfied to see that one of the two shots I had fired as he charged down upon

me had taken effect. The bullet had entered below the right eye, and only just

missed the brain. Unfortunately it was a steel one which Spooner had unluckily

brought in his ammunition bag by mistake; still one would have thought that a shot

of this kind, even with a hard bullet, would at least have checked the lion for

the moment. As a matter of fact, however, it went clean through him without

having the slightest stopping effect. My last bullet, which was of soft lead, had

entered close to the right eye and embedded itself in the brain. By this time

it had grown almost dark, so I left the two dead lions where they lay and rode

for camp, which I was lucky enough to reach without further adventure or mishap.

I may mention here that early next morning two other lions were found devouring

the one we had first shot; but they had not had time to do much damage, and the

head, which I have had mounted, makes a very fine trophy indeed. The lion that

mauled Bhoota was untouched.

On my arrival in camp I found that everything that was

possible was being done for poor Bhoota by Dr. McCulloch, the same who had

travelled up with me to Tsavo and shot the ostrich from the train on my first

arrival in the country, and who was luckily on the spot. His wounds had been

skilfully dressed, the broken leg put in splints, and under the influence of a

soothing draught the poor fellow was soon sleeping peacefully. At first we had

great hope of saving both life and limb, and certainly for some days he seemed

to be getting on as well as could be expected. The wounds, however, were very bad

ones, especially those on the leg where the long tusks had met through and

through the flesh, leaving over a dozen deep tooth marks; the arm, though

dreadfully mauled, soon healed. It was wonderful to notice how cheerfully the

old shikari, bore it all, and a pleasure to listen to his tale of how he would

have his revenge on the whole tribe of lions as soon as he was able to get

about again. But alas, his shikar was over. The leg got rapidly worse, and

mortification setting in, it had to be amputated half way up the thigh.

Dr. Winston Waters performed the operation most skilfully,

and curiously enough the operating table was canopied with the skin of the lion

which had been responsible for the injury. Bhoota made a good recovery from the

operation, but seemed to lose heart when he found that he had only one leg

left, as according to his ideas he had now but a poor chance of being allowed

to enter Heaven. We did all that was possible for him, and Spooner especially

could not have looked after a brother more tenderly; but to our great sorrow he

sank gradually, and died on July 19.

Published on November 22, 2012 01:00

November 21, 2012

Tracks

Along a creek bed, Parker found these tracks of deer and raccoon. The deer, with its cloven hoof, leaves a print that looks like paired half-moons.

The raccoon's paws have five fingers. The hind pawprints generally include claw marks, but the forefoot claws may not make much of an impression. In that case, the track looks like the impress of a child's hand.

Creek banks are ideal for finding prints of all kinds. If you look closely, you'll see a few other kinds mixed in with the prominent coon and deer signs.

Photography by Parker Grice

Published on November 21, 2012 01:30

November 18, 2012

How It Feels to Be Attacked by a Shark

What I’m Reading:

How It Feels to Be Attacked by a Shark:

And Other Amazing Life-or Death Situations

edited by Michelle Hamer

Thirty-seven first-person accounts of being in difficult

situations, from weighing 500 pounds to choking on a cheeseburger. I, of

course, grabbed it for the shark attack and found several other stories from,

shall we say, the Night Side of Nature:

-attacked by a crocodile

-mauled by a Rottweiler

-debilitated by dengue fever.

These are fascinating accounts, full of details you don’t usually hear about. The shark victim,

for instance, mentions trying to slow his heartbeat when he saw the great white

approach because he assumed the shark would sense it. The Rottweiler victim

frankly mentions having been bitten on her breast. The crocodile victim notices

the “beautiful golden-flecked eyes” of her attacker.

The stories are brief; I found myself devouring them like

potato chips. And then I took a bite that made me spit: “How It Feels to Be

Abducted by Aliens.” Surprisingly, I here encountered yet another bite on the

breast; our narrator bites in self-defense as a couple of lady aliens try to

take liberties with him, even though, as he says, one of them has hair “like

Farrah Fawcett’s when she was in Charlie’s Angels.” Having bitten off the alien’s

nipple, the gentleman is later asked “if I checked for it in my bowel

movements, but that never crossed my mind.”

It didn’t really seem worth going on after that story. I

leafed ahead and found the next story was called “How It Feels to Be an Animal

Psychic.” Yeah, I’m quitting here.

Published on November 18, 2012 22:30

November 17, 2012

Katydids on Lily

Published on November 17, 2012 22:44

November 14, 2012

Wildlife Classic: The Waters of Death

by Erckmann-Chatrian

[Note: Like many of the classics, this is not PC.]

The warm mineral waters of

Spinbronn, situated in the Hundsrueck, several leagues from Pirmesens, formerly

enjoyed a magnificent reputation. All who were afflicted with gout or gravel in

Germany repaired thither; the savage aspect of the country did not deter them.

They lodged in pretty cottages at the head of the defile; they bathed in the

cascade, which fell in large sheets of foam from the summit of the rocks; they

drank one or two decanters of mineral water daily, and the doctor of the place,

Daniel Haselnoss, who distributed his prescriptions clad in a great wig and

chestnut coat, had an excellent practice.

To-day the waters of Spinbronn

figure no longer in the "Codex"; in this poor village one no longer

sees anyone but a few miserable woodcutters, and, sad to say, Dr. Haselnoss has

left!

All this resulted from a series

of very strange catastrophes which lawyer Bremer of Pirmesens told me about the

other day.

You should know, Master Frantz

(said he), that the spring of Spinbronn issues from a sort of cavern, about

five feet high and twelve or fifteen feet wide; the water has a warmth of

sixty-seven degrees Centigrade; it is salt. As for the cavern, entirely covered

without with moss, ivy, and brushwood, its depth is unknown because the hot

exhalations prevent all entrance.

Nevertheless, strangely enough,

it was noticed early in the last century that birds of the

neighborhood--thrushes, doves, hawks--were engulfed in it in full flight, and

it was never known to what mysterious influence to attribute this particular.

In 1801, at the height of the

season, owing to some circumstance which is still unexplained, the spring

became more abundant, and the bathers, walking below on the greensward, saw a

human skeleton as white as snow fall from the cascade.

You may judge, Master Frantz,

of the general fright; it was thought naturally that a murder had been

committed at Spinbronn in a recent year, and that the body of the victim had

been thrown in the spring. But the skeleton weighed no more than a dozen

francs, and Haselnoss concluded that it must have sojourned more than three

centuries in the sand to have become reduced to such a state of desiccation.

This very plausible reasoning

did not prevent a crowd of patrons, wild at the idea of having drunk the saline

water, from leaving before the end of the day; those worst afflicted with gout

and gravel consoled themselves. But the overflow continuing, all the rubbish,

slime, and detritus which the cavern contained was disgorged on the following

days; a veritable bone-yard came down from the mountain: skeletons of animals

of every kind--of quadrupeds, birds, and reptiles--in short, all that one could

conceive as most horrible.

Haselnoss issued a pamphlet

demonstrating that all these bones were derived from an antediluvian world: that

they were fossil bones, accumulated there in a sort of funnel during the

universal flood--that is to say, four thousand years before Christ, and that,

consequently, one might consider them as nothing but stones, and that it was

needless to be disgusted. But his work had scarcely reassured the gouty when,

one fine morning, the corpse of a fox, then that of a hawk with all its

feathers, fell from the cascade.

It was impossible to establish

that these remains antedated the Flood. Anyway, the disgust was so great that

everybody tied up his bundle and went to take the waters elsewhere.

"How infamous!" cried

the beautiful ladies--"how horrible! So that's what the virtue of these

mineral waters came from! Oh, 'twere better to die of gravel than continue such

a remedy!"

At the end of a week there

remained at Spinbronn only a big Englishman who had gout in his hands as well

as in his feet, who had himself addressed as Sir Thomas Hawerburch, Commodore;

and he brought a large retinue, according to the usage of a British subject in

a foreign land.

This personage, big and fat,

with a florid complexion, but with hands simply knotted with gout, would have

drunk skeleton soup if it would have cured his infirmity. He laughed heartily

over the desertion of the other sufferers, and installed himself in the

prettiest _chalet_ at half price, announcing his design to pass the winter at

Spinbronn.

*

(Here lawyer Bremer slowly

absorbed an ample pinch of snuff as if to quicken his reminiscences; he shook

his laced ruff with his finger tips and continued:)

*

Five or six years before the

Revolution of 1789, a young doctor of Pirmesens, named Christian Weber, had

gone out to San Domingo in the hope of making his fortune. He had actually

amassed some hundred thousand francs m the exercise of his profession when the

negro revolt broke out.

I need not recall to you the

barbarous treatment to which our unfortunate fellow countrymen were subjected

at Haiti. Dr. Weber had the good luck to escape the massacre and to save part of

his fortune. Then he traveled in South America, and especially in French

Guiana. In 1801 he returned to Pirmesens, and established himself at Spinbronn,

where Dr. Haselnoss made over his house and defunct practice.

Christian Weber brought with

him an old negress called Agatha: a frightful creature, with a flat nose and

lips as large as your fist, and her head tied up in three bandanas of

razor-edged colors. This poor old woman adored red; she had earrings which hung

down to her shoulders, and the mountaineers of Hundsrueck came from six leagues

around to stare at her.

As for Dr. Weber, he was a

tall, lean man, invariably dressed in a sky-blue coat with codfish tails and

deerskin breeches. He wore a hat of flexible straw and boots with bright yellow

tops, on the front of which hung two silver tassels. He talked little; his

laugh was like a nervous attack, and his gray eyes, usually calm and

meditative, shone with singular brilliance at the least sign of contradiction.

Every morning he fetched a turn round about the mountain, letting his horse

ramble at a venture, whistling forever the same tune, some negro melody or

other. Lastly, this rum chap had brought from Haiti a lot of bandboxes filled

with queer insects--some black and reddish brown, big as eggs; others little

and shimmering like sparks. He seemed to set greater store by them than by his

patients, and, from time to time, on coming back from his rides, he brought a

quantity of butterflies pinned to his hat brim.

Scarcely was he settled in

Haselnoss's vast house when he peopled the back yard with outlandish

birds--Barbary geese with scarlet cheeks, Guinea hens, and a white peacock,

which perched habitually on the garden wall, and which divided with the negress

the admiration of the mountaineers.

If I enter into these details,

Master Frantz, it's because they recall my early youth; Dr. Christian found

himself to be at the same time my cousin and my tutor, and as early as on his

return to Germany he had come to take me and install me in his house at Spinbronn.

The black Agatha at first sight inspired me with some fright, and I only got

seasoned to that fantastic visage with considerable difficulty; but she was

such a good woman--she knew so well how to make spiced patties, she hummed such

strange songs in a guttural voice, snapping her fingers and keeping time with a

heavy shuffle, that I ended by taking her in fast friendship.

Dr. Weber was naturally thick

with Sir Thomas Hawerburch, as representing the only one of his clientele then

in evidence, and I was not slow in perceiving that these two eccentrics held

long conventicles together. They conversed on mysterious matters, on the

transmission of fluids, and indulged in certain odd signs which one or the

other had picked up in his voyages--Sir Thomas in the Orient, and my tutor in

America. This puzzled me greatly. As children will, I was always lying in wait

for what they seemed to want to conceal from me; but despairing in the end of

discovering anything, I took the course of questioning Agatha, and the poor old

woman, after making me promise to say nothing about it, admitted that my tutor

was a sorcerer.

For the rest, Dr. Weber

exercised a singular influence over the mind of this negress, and this woman,

habitually so gay and forever ready to be amused by nothing, trembled like a

leaf when her master's gray eyes chanced to alight on her.

All this, Master Frantz, seems

to have no bearing on the springs of Spinbronn. But wait, wait--you shall see

by what a singular concourse of circumstances my story is connected with it.

I told you that birds darted

into the cavern, and even other and larger creatures. After the final departure

of the patrons, some of the old inhabitants of the village recalled that a

young girl named Louise Mueller, who lived with her infirm old grandmother in a

cottage on the pitch of the slope, had suddenly disappeared half a hundred

years before. She had gone out to look for herbs in the forest, and there had

never been any more news of her afterwards, except that, three or four days

later, some woodcutters who were descending the mountain had found her sickle

and her apron a few steps from the cavern.

From that moment it was evident

to everyone that the skeleton which had fallen from the cascade, on the subject

of which Haselnoss had turned such fine phrases, was no other than that of

Louise Mueller. The poor girl had doubtless been drawn into the gulf by the

mysterious influence which almost daily overcame weaker beings!

What could this influence be?

None knew. But the inhabitants of Spinbronn, superstitious like all

mountaineers, maintained that the devil lived in the cavern, and terror spread

in the whole region.

*

Now one afternoon in the middle

of the month of July, 1802, my cousin undertook a new classification of the

insects in his bandboxes. He had secured several rather curious ones the

preceding afternoon. I was with him, holding the lighted candle with one hand

and with the other a needle which I heated red-hot.

Sir Thomas, seated, his chair

tipped back against the sill of a window, his feet on a stool, watched us work,

and smoked his cigar with a dreamy air.

I stood in with Sir Thomas

Hawerburch, and I accompanied him every day to the woods in his carriage. He

enjoyed hearing me chatter in English, and wished to make of me, as he said, a

thorough gentleman.

The butterflies labeled, Dr.

Weber at last opened the box of the largest insects, and said:

"Yesterday I secured a

magnificent horn beetle, the great _Lucanus cervus_ of the oaks of the Hartz.

It has this peculiarity--the right claw divides in five branches. It's a rare

specimen."

At the same time I offered him

the needle, and as he pierced the insect before fixing it on the cork, Sir

Thomas, until then impassive, got up, and, drawing near a bandbox, he began to

examine the crab spider of Guiana with a feeling of horror which was strikingly

portrayed on his fat vermilion face.

"That is certainly,"

he cried, "the most frightful work of the creation. The mere sight of

it--it makes me shudder!"

In truth, a sudden pallor

overspread his face.

"Bah!" said my tutor,

"all that is only a prejudice from childhood--one hears his nurse cry

out--one is afraid--and the impression sticks. But if you should consider the

spider with a strong microscope, you would be astonished at the finish of his

members, at their admirable arrangement, and even at their elegance."

"It disgusts me,"

interrupted the commodore brusquely. "Pouah!"

It had turned over in his

fingers.

"Oh! I don't know

why," he declared, "spiders have always frozen my blood!"

Dr. Weber began to laugh, and

I, who shared the feelings of Sir Thomas, exclaimed:

"Yes, cousin, you ought to

take this villainous beast out of the box--it is disgusting--it spoils all the

rest."

"Little chump," he

said, his eyes sparkling, "what makes you look at it? If you don't like

it, go take yourself off somewhere."

Evidently he had taken offense;

and Sir Thomas, who was then before the window contemplating the mountain,

turned suddenly, took me by the hand, and said to me in a manner full of good

will:

"Your tutor, Frantz, sets

great store by his spider; we like the trees better--the verdure. Come, let's

go for a walk."

"Yes, go," cried the

doctor, "and come back for supper at six o'clock."

Then raising his voice:

"No hard feelings, Sir

Hawerburch."

The commodore replied

laughingly, and we got into the carriage, which was always waiting in front of

the door of the house.

Sir Thomas wanted to drive

himself and dismissed his servant. He made me sit beside him on the same seat

and we started off for Rothalps.

While the carriage was slowly

ascending the sandy path, an invincible sadness possessed itself of my spirit.

Sir Thomas, on his part, was grave. He perceived my sadness and said:

"You don't like spiders,

Frantz, nor do I either. But thank Heaven, there aren't any dangerous ones in

this country. The crab spider which your tutor has in his box comes from French

Guiana. It inhabits the great, swampy forests filled with warm vapors, with

scalding exhalations; this temperature is necessary to its life. Its web, or

rather its vast snare, envelops an entire thicket. In it it takes birds as our

spiders take flies. But drive these disgusting images from your mind, and drink

a swallow of my old Burgundy."

Then turning, he raised the

cover of the rear seat, and drew from the straw a sort of gourd from which he

poured me a full bumper in a leather goblet.

When I had drunk all my good

humor returned and I began to laugh at my fright.

The carriage was drawn by a

little Ardennes horse, thin and nervous as a goat, which clambered up the

nearly perpendicular path. Thousands of insects hummed in the bushes. At our

right, at a hundred paces or more, the somber outskirts of the Rothalp forests

extended below us, the profound shades of which, choked with briers and foul

brush, showed here and there an opening filled with light. On our left tumbled

the stream of Spinbronn, and the more we climbed the more did its silvered

sheets, floating in the abyss, grow tinged with azure and redouble their sound

of cymbals.

I was captivated by this

spectacle. Sir Thomas, leaning back in the seat, his knees as high as his chin,

abandoned himself to his habitual reveries, while the horse, laboring with his

feet and hanging his head on his chest as a counter-weight to the carriage,

held on as if suspended on the flank of the rock. Soon, however, we reached a

pitch less steep: the haunt of the roebuck, surrounded by tremulous shadows. I

always lost my head, and my eyes too, in an immense perspective. At the

apparition of the shadows I turned my head and saw the cavern of Spinbronn

close at hand. The encompassing mists were a magnificent green, and the stream

which, before falling, extends over a bed of black sand and pebbles, was so

clear that one would have thought it frozen if pale vapors did not follow its

surface.

The horse had just stopped of

his own accord to breathe; Sir Thomas, rising, cast his eye over the

countryside.

"How calm everything

is!" said he.

Then, after an instant of

silence:

"If you weren't here,

Frantz, I should certainly bathe in the basin."

"But, Commodore,"

said I, "why not bathe? I would do well to stroll around in the

neighborhood. On the next hill is a great glade filled with wild strawberries.

I'll go and pick some. I'll be back in an hour."

"Ha! I should like to,

Frantz; it's a good idea. Dr. Weber contends that I drink too much Burgundy.

It's necessary to offset wine with mineral water. This little bed of sand

pleases me."

Then, having set both feet on

the ground, he hitched the horse to the trunk of a little birch and waved his

hand as if to say:

"You may go."

I saw him sit down on the moss

and draw off his boots. As I moved away he turned and called out:

"In an hour, Frantz."

They were his last words.

An hour later I returned to the

spring. The horse, the carriage, and the clothes of Sir Thomas alone met my

eyes. The sun was setting. The shadows were getting long. Not a bird's song

under the foliage, not the hum of an insect in the tall grass. A silence like

death looked down on this solitude! The silence frightened me. I climbed up on

the rock which overlooks the cavern; I looked to the right and to the left.

Nobody! I called. No answer! The sound of my voice, repeated by the echoes,

filled me with fear. Night settled down slowly. A vague sense of horror

oppressed me. Suddenly the story of the young girl who had disappeared occurred

to me; and I began to descend on the run; but, arriving before the cavern, I

stopped, seized with unaccountable terror: in casting a glance in the deep

shadows of the spring I had caught sight of two motionless red points. Then I

saw long lines wavering in a strange manner in the midst of the darkness, and

that at a depth where no human eye had ever penetrated. Fear lent my sight, and

all my senses, an unheard-of subtlety of perception. For several seconds I

heard very distinctly the evening plaint of a cricket down at the edge of the

wood, a dog barking far away, very far in the valley. Then my heart, compressed

for an instant by emotion, began to beat furiously and I no longer heard

anything!

Then uttering a horrible cry, I

fled, abandoning the horse, the carriage. In less than twenty minutes, bounding

over the rocks and brush, I reached the threshold of our house, and cried in a

stifled voice:

"Run! Run! Sir Hawerburch

is dead! Sir Hawerburch is in the cavern--!"

After these words, spoken in

the presence of my tutor, of the old woman Agatha, and of two or three people

invited in that evening by the doctor, I fainted. I have learned since that

during a whole hour I raved deliriously.

The whole village had gone in

search of the commodore. Christian Weber hurried them off. At ten o'clock in

the evening all the crowd came back, bringing the carriage, and in the carriage

the clothes of Sir Hawerburch. They had discovered nothing. It was impossible to

take ten steps in the cavern without being suffocated.

During their absence Agatha and

I waited, sitting in the chimney corner. I, howling incoherent words of terror;

she, with hands crossed on her knees, eyes wide open, going from time to time

to the window to see what was taking place, for from the foot of the mountain

one could see torches flitting in the woods. One could hear hoarse voices, in

the distance, calling to each other in the night.

At the approach of her master,

Agatha began to tremble. The doctor entered brusquely, pale, his lips

compressed, despair written on his face. A score of woodcutters followed him

tumultuously, in great felt hats with wide brims--swarthy visaged--shaking the

ash from their torches. Scarcely was he in the hall when my tutor's glittering

eyes seemed to look for something. He caught sight of the negress, and without

a word having passed between them, the poor woman began to cry:

"No! no! I don't want

to!"

"And I wish it,"

replied the doctor in a hard tone.

One would have said that the

negress had been seized by an invincible power. She shuddered from head to

foot, and Christian Weber showing her a bench, she sat down with a corpse-like

stiffness.

All the bystanders, witnesses

of this shocking spectacle, good folk with primitive and crude manners, but

full of pious sentiments, made the sign of the cross, and I who knew not then,

even by name, of the terrible magnetic power of the will, began to tremble,

believing that Agatha was dead.

Christian Weber approached the

negress, and making a rapid pass over her forehead:

"Are you there?" said

he.

"Yes, master."

"Sir Thomas

Hawerburch?"

At these words she shuddered

again.

"Do you see him?"

"Yes--yes," she

gasped in a strangling voice, "I see him."

"Where is he?"

"Up there--in the back of

the cavern--dead!"

"Dead!" said the

doctor, "how?"

"The spider--Oh! the crab

spider--Oh!--"

"Control your

agitation," said the doctor, who was quite pale, "tell us

plainly--"

"The crab spider has him

by the throat--he is there--at the back--under the rock--wound round by

webs--Ah!"

Christian Weber cast a cold

glance toward his assistants, who, crowding around, with their eyes sticking

out of their heads, were listening intently, and I heard him murmur:

"It's horrible!

horrible!"

Then he resumed:

"You see him?"

"I see him--"

"And the spider--is it

big?"

"Oh, master, never--never

have I seen such a large one--not even on the banks of the Mocaris--nor in the

lowlands of Konanama. It is as large as my head--!"

There was a long silence. All

the assistants looked at each other, their faces livid, their hair standing up.

Christian Weber alone seemed calm; having passed his hand several times over

the negress's forehead, he continued:

"Agatha, tell us how death

befell Sir Hawerburch."

"He was bathing in the

basin of the spring--the spider saw him from behind, with his bare back. It was

hungry, it had fasted for a long time; it saw him with his arms on the water.

Suddenly it came out like a flash and placed its fangs around the commodore's

neck, and he cried out: 'Oh! oh! my God!' It stung and fled. Sir Hawerburch

sank down in the water and died. Then the spider returned and surrounded him

with its web, and he floated gently, gently, to the back of the cavern. It drew

in on the web. Now he is all black."

The doctor, turning to me, who

no longer felt the shock, asked:

"Is it true, Frantz, that

the commodore went in bathing?"

"Yes, Cousin

Christian."

"At what time?"

"At four o'clock."

"At four o'clock--it was

very warm, wasn't it?"

"Oh, yes!"

"It's certainly so,"

said he, striking his forehead. "The monster could come out without

fear--"

He pronounced a few

unintelligible words, and then, looking toward the mountaineers:

"My friends," he

cried, "that is where this mass of debris came from--of skeletons--which spread

terror among the bathers. That is what has ruined you all--it is the crab spider!

It is there--hidden in its web--awaiting its prey in the back of the cavern!

Who can tell the number of its victims?"

And full of fury, he led the

way, shouting:

"Firewood! Firewood!"

The woodcutters followed him,

vociferating.

Ten minutes later two large

wagons laden with fagots were slowly mounting the slope. A long file of

woodcutters, their backs bent double, followed, enveloped in the somber night.

My tutor and I walked ahead, leading the horses by their bridles, and the

melancholy moon vaguely lighted this funereal march. From time to time the

wheels grated. Then the carts, raised by the irregularities of the rocky road,

fell again in the track with a heavy jolt.

As we drew near the cavern, on

the playground of the roebucks, our cortege halted. The torches were lit, and

the crowd advanced toward the gulf. The limpid water, running over the sand,

reflected the bluish flame of the resinous torches, the rays of which revealed

the tops of the black firs leaning over the rock.

"This is the place to

unload," the doctor then said. "It's necessary to block up the mouth

of the cavern."

And it was not without a

feeling of terror that each undertook the duty of executing his orders. The

fagots fell from the top of the loads. A few stakes driven down before the

opening of the spring prevented the water from carrying them away.

Toward midnight the mouth of

the cavern was completely closed. The water running over spread to both sides on

the moss. The top fagots were perfectly dry; then Dr. Weber, supplying himself

with a torch, himself lit the fire. The flames ran from twig to twig with an

angry crackling, and soon leaped toward the sky, chasing clouds of smoke before

them.

It was a strange and savage

spectacle, the great pile with trembling shadows lit up in this way.

This cavern poured forth black

smoke, unceasingly renewed and disgorged. All around stood the woodcutters,

somber, motionless, expectant, their eyes fixed on the opening; and I, although

trembling from head to foot in fear, could not tear away my gaze.

It was a good quarter of an

hour that we waited, and Dr. Weber was beginning to grow impatient, when a

black object, with long hooked claws, appeared suddenly in the shadow and

precipitated itself toward the opening.

A cry resounded about the pyre.

The spider, driven back by the

live coals, reentered its cave. Then, smothered doubtless by the smoke, it

returned to the charge and leaped out into the midst of the flames. Its long

legs curled up. It was as large as my head, and of a violet red.

One of the woodcutters, fearing

lest it leap clear of the fire, threw his hatchet at it, and with such good aim

that on the instant the fire around it was covered with blood. But soon the flames

burst out more vigorously over it and consumed the horrible destroyer.

*

Such, Master Frantz, was the

strange event which destroyed the fine reputation which the waters of Spinbronn

formerly enjoyed. I can certify the scrupulous precision of my account. But as

for giving you an explanation, that would be impossible for me to do. At the

same time, allow me to tell you that it does not seem to me absurd to admit

that a spider, under the influence of a temperature raised by thermal waters,

which affords the same conditions of life and development as the scorching

climates of Africa and South America, should attain a fabulous size. It was

this same extreme heat which explains the prodigious exuberance of the

antediluvian creation!

However that may be, my tutor,

judging that it would be impossible after this event to reestablish the waters

of Spinbronn, sold the house back to Haselnoss, in order to return to America

with his negress and collections. I was sent to board in Strasbourg, where I

remained until 1809.

The great political events of

the epoch then absorbing the attention of Germany and France explain why the

affair I have just told you about passed completely unobserved.

Published on November 14, 2012 22:33

November 13, 2012

Ranger vs. Leopard

Published on November 13, 2012 22:30

November 12, 2012

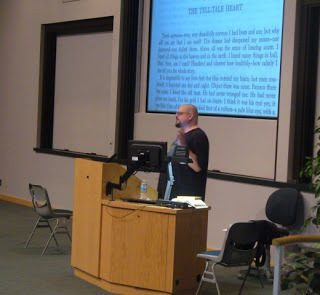

Grice Yammers about Poe

Opening day: The Tell-Tale Heart

Thanks to the folks at the Selim Center in Minneapolis, who recently hosted me for a six-week series on the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Luckily for me, they didn't realize I'd probably have showed up to talk about Poe for free.

Break time: Students menaced by an eerie figure.

I heard all things in the heaven and in the

earth. I heard many things in hell.

--"The Tell-Tale Heart,"

by Edgar Allan Poe

Published on November 12, 2012 23:00

November 11, 2012

Animal Attack Movies: Alligator

John Sayles is famous for dramas

so low-key they put me to sleep. Like, for example, Lone Star, probably the least

exciting movie about accidental incest ever made. He’s not bad; in fact, he’s

very good; it’s just that I drink coffee and demand a life full of excitement.

Long ago, however, Mr. Sayles

financed his arty efforts by writing genre pictures, like the satirical werewolf

movie The Howling and the satirical animal attack movie Piranha. This is the

stuff that makes me like him. My favorite is Alligator (1980; directed by Lewis

Teague with an admirable efficiency and a curious interest in exploding

vehicles). It’s the venerable gators-in-the-sewers legend, ramped up with

growth hormones and corporate corruption.

Most filmmakers can’t do humor and horror at

the same time, not REAL horror, but Sayles and Teague manage it. There’s a night scene in which little boys are playing pirates, and one of them has to “walk

the plank” over a backyard pool, and at the last minute he sees something in

the water. . .

Published on November 11, 2012 23:00

Hummingbird

"This was the most territorial aggressive little thing! She literally sat beneath that feeder like a guard dog within ten minutes of my hanging it. I am pretty sure this is a female ruby throat. At the neighbor's house with the eight feeders, there is only one male ruby throat. So I am guessing she is a rebel daughter or a wayward wife who decided to run away from the fray. That woman goes through a four pound bag of sugar a day keeping those feeders filled."

--Dee Puett, photographer

Published on November 11, 2012 00:00