Gordon Grice's Blog, page 14

October 20, 2016

Edgar Allan Poe: The Dead Man to His Lover

I succumbed to a fierce fever. After some few days of pain, and many of dreamy delirium replete with ecstasy, there came upon me a breathless and motionless torpor; and this was termed Death by those who stood around me.

My condition did not deprive me of sentience. It appeared to me not greatly dissimilar to the extreme quiescence of him who, having slumbered long and profoundly, lying motionless and fully prostrate in a midsummer noon, begins to steal slowly back into consciousness, through the mere sufficiency of his sleep, and without being awakened by external disturbances.

I breathed no longer. The pulses were still. The heart had ceased to beat. Volition had not departed, but was powerless. The senses were unusually active, although eccentrically so—assuming often each other's functions at random. The taste and the smell were inextricably confounded, and became one sentiment, abnormal and intense. The rose-water with which your tenderness had moistened my lips to the last, affected me with sweet fancies of flowers. The eyelids, transparent and bloodless, offered no complete impediment to vision. As volition was in abeyance, the balls could not roll in their sockets, but all objects within the range of the visual hemisphere were seen with more or less distinctness; the rays which fell upon the external retina, or into the corner of the eye, producing a more vivid effect than those which struck the front or interior surface. Yet, in the former instance, this effect was so far anomalous that I appreciated it only as sound—sound sweet or discordant as the matters presenting themselves at my side were light or dark in shade—curved or angular in outline. The hearing, at the same time, although excited in degree, was not irregular in action—estimating real sounds with an extravagance of precision, not less than of sensibility. Touch had undergone a modification more peculiar. Its impressions were tardily received, but pertinaciously retained, and resulted always in the highest physical pleasure. Thus the pressure of your sweet fingers upon my eyelids, at first only recognised through vision, at length, long after their removal, filled my whole being with a sensual delight immeasurable.

All my perceptions were purely sensual. The materials furnished the passive brain by the senses were not in the least degree wrought into shape by the deceased understanding. Of pain there was some little; of pleasure there was much; but of moral pain or pleasure none at all. Thus your wild sobs floated into my ear with all their mournful cadences, and were appreciated in their every variation of sad tone; but they were soft musical sounds and no more; they conveyed to the extinct reason no intimation of the sorrows which gave them birth; while the large and constant tears which fell upon my face, telling the bystanders of a heart which broke, thrilled every fibre of my frame with ecstasy alone.

The day waned; and, as its light faded away, I became possessed by a vague uneasiness—an anxiety such as the sleeper feels when sad real sounds fall continuously within his ear—low distant bell-tones, solemn, at long but equal intervals, and mingling with melancholy dreams. Night arrived; and with its shadows a heavy discomfort. It oppressed my limbs with the oppression of some dull weight, and was palpable. There was also a moaning sound, not unlike the distant reverberation of surf, but more continuous, which, beginning with the first twilight, had grown in strength with the darkness. Suddenly lights were brought into the room, and this reverberation became forthwith interrupted into frequent unequal bursts of the same sound, but less dreary and less distinct. The ponderous oppression was in a great measure relieved; and, issuing from the flame of each lamp, (for there were many,) there flowed unbrokenly into my ears a strain of melodious monotone. And when now, approaching the bed upon which I lay outstretched, you sat gently by my side, breathing odor from your sweet lips, and pressing them upon my brow, there arose tremulously within my bosom, and mingling with the merely physical sensations which circumstances had called forth, a something akin to sentiment itself—a feeling that, half appreciating, half responded to your earnest love and sorrow; but this feeling took no root in the pulseless heart, and seemed indeed rather a shadow than a reality, and faded quickly away, first into extreme quiescence, and then into a purely sensual pleasure as before.

And now, from the wreck and the chaos of the usual senses, there appeared to have arisen within me a sixth, all perfect. In its exercise I found a wild delight—yet a delight still physical, inasmuch as the understanding had in it no part. Motion in the animal frame had fully ceased. No muscle quivered; no nerve thrilled; no artery throbbed. But there seemed to have sprung up in the brain, that of which no words could convey even an indistinct conception. Let me term it a mental pendulous pulsation. It was the embodiment of Time. By the absolute equalization of this movement had the cycles of the firmamental orbs themselves, been adjusted. By its aid I measured the irregularities of the clock upon the mantel, and of the watches of the attendants. Their tickings came sonorously to my ears. The slightest deviations from the true proportion—and these deviations were omni-prevalent—affected me just as violations of truth were wont, on earth, to affect the moral sense. Although no two of the time-pieces in the chamber struck the individual seconds accurately together, yet I had no difficulty in holding steadily in mind the tones, and the errors of each. And this keen, perfect, self-existing sentiment of duration was the first step of the soul upon the threshold of the Eternity.

It was midnight; and you still sat by my side. All others had departed from the chamber of Death. They had deposited me in the coffin. The lamps burned flickeringly; for this I knew by the tremulousness of the monotonous strains. But, suddenly these strains diminished in distinctness and in volume. Finally they ceased. The perfume in my nostrils died away. Forms affected my vision no longer. The oppression of the Darkness uplifted itself from my bosom. A dull shock like that of electricity pervaded my frame.

I appreciated the direful change now in operation upon the flesh, and, as the dreamer is sometimes aware of the bodily presence of one who leans over him, so I still dully felt that you sat by my side. When the noon of the second day came, I was conscious of those movements which displaced you from my side, which confined me within the coffin, which deposited me within the hearse, which bore me to the grave, which lowered me within it, which heaped heavily the mould upon me, and which thus left me, in blackness and corruption, to my solemn slumbers with the worm.

Published on October 20, 2016 09:00

October 15, 2016

How to Survive a Deer or Moose Attack

Your favorite nature writer is quoted in this informative article:

How to Survive a Deer or Moose Attack:

And if you want more of my take on the subject of dangerous deer, follow the "saw their own reflection" link to an article of mine on Gizmodo. Or, simply dip into your copy of The Book of Deadly Animals.

How to Survive a Deer or Moose Attack:

They’ll attack hikers in the wilderness, gore people tending their gardens, and there have been multiple cases of bucks busting through the windows of houses and business because they saw their own reflection in the glass. Some bucks will even hold a grudge, like one that attacked a driver afterthey had hit it with their car.

And if you want more of my take on the subject of dangerous deer, follow the "saw their own reflection" link to an article of mine on Gizmodo. Or, simply dip into your copy of The Book of Deadly Animals.

Published on October 15, 2016 16:33

October 12, 2016

Sweet Deal on Cabinet of Curiosities

The publisher is running a nice deal on Cabinet of Curiosities through Halloween, along with the major online stores. If you've been hesitating over the price, here's your chance.

Weekly Deals 10/8/16 - Workman Publishing:

Weekly Deals 10/8/16 - Workman Publishing:

Published on October 12, 2016 22:00

October 1, 2016

The Gray Wolf

An old-fashioned werewolf story.

The Gray Wolf

by George MacDonald

One evening-twilight in spring, a young English student, who had wandered northwards as far as the outlying fragments of Scotland called the Orkney and Shetland Islands, found himself on a small island of the latter group, caught in a storm of wind and hail, which had come on suddenly. It was in vain to look about for any shelter; for not only did the storm entirely obscure the landscape, but there was nothing around him save a desert moss.

At length, however, as he walked on for mere walking's sake, he found himself on the verge of a cliff, and saw, over the brow of it, a few feet below him, a ledge of rock, where he might find some shelter from the blast, which blew from behind. Letting himself down by his hands, he alighted upon something that crunched beneath his tread, and found the bones of many small animals scattered about in front of a little cave in the rock, offering the refuge he sought. He went in, and sat upon a stone. The storm increased in violence, and as the darkness grew he became uneasy, for he did not relish the thought of spending the night in the cave. He had parted from his companions on the opposite side of the island, and it added to his uneasiness that they must be full of apprehension about him. At last there came a lull in the storm, and the same instant he heard a footfall, stealthy and light as that of a wild beast, upon the bones at the mouth of the cave. He started up in some fear, though the least thought might have satisfied him that there could be no very dangerous animals upon the island. Before he had time to think, however, the face of a woman appeared in the opening. Eagerly the wanderer spoke. She started at the sound of his voice. He could not see her well, because she was turned towards the darkness of the cave.

"Will you tell me how to find my way across the moor to Shielness?" he asked.

"You cannot find it to-night," she answered, in a sweet tone, and with a smile that bewitched him, revealing the whitest of teeth.

"What am I to do, then?"

"My mother will give you shelter, but that is all she has to offer."

"And that is far more than I expected a minute ago," he replied. "I shall be most grateful."

She turned in silence and left the cave. The youth followed.

She was barefooted, and her pretty brown feet went catlike over the sharp stones, as she led the way down a rocky path to the shore. Her garments were scanty and torn, and her hair blew tangled in the wind. She seemed about five and twenty, lithe and small. Her long fingers kept clutching and pulling nervously at her skirts as she went. Her face was very gray in complexion, and very worn, but delicately formed, and smooth-skinned. Her thin nostrils were tremulous as eyelids, and her lips, whose curves were faultless, had no colour to give sign of indwelling blood. What her eyes were like he could not see, for she had never lifted the delicate films of her eyelids.

At the foot of the cliff, they came upon a little hut leaning against it, and having for its inner apartment a natural hollow within. Smoke was spreading over the face of the rock, and the grateful odour of food gave hope to the hungry student. His guide opened the door of the cottage; he followed her in, and saw a woman bending over a fire in the middle of the floor. On the fire lay a large fish broiling. The daughter spoke a few words, and the mother turned and welcomed the stranger. She had an old and very wrinkled, but honest face, and looked troubled. She dusted the only chair in the cottage, and placed it for him by the side of the fire, opposite the one window, whence he saw a little patch of yellow sand over which the spent waves spread themselves out listlessly. Under this window there was a bench, upon which the daughter threw herself in an unusual posture, resting her chin upon her hand. A moment after, the youth caught the first glimpse of her blue eyes. They were fixed upon him with a strange look of greed, amounting to craving, but, as if aware that they belied or betrayed her, she dropped them instantly. The moment she veiled them, her face, notwithstanding its colourless complexion, was almost beautiful.

When the fish was ready, the old woman wiped the deal table, steadied it upon the uneven floor, and covered it with a piece of fine table-linen. She then laid the fish on a wooden platter, and invited the guest to help himself. Seeing no other provision, he pulled from his pocket a hunting knife, and divided a portion from the fish, offering it to the mother first.

"Come, my lamb," said the old woman; and the daughter approached the table. But her nostrils and mouth quivered with disgust.

The next moment she turned and hurried from the hut.

"She doesn't like fish," said the old woman, "and I haven't anything else to give her."

"She does not seem in good health," he rejoined.

The woman answered only with a sigh, and they ate their fish with the help of a little rye bread. As they finished their supper, the youth heard the sound as of the pattering of a dog's feet upon the sand close to the door; but ere he had time to look out of the window, the door opened, and the young woman entered. She looked better, perhaps from having just washed her face. She drew a stool to the corner of the fire opposite him. But as she sat down, to his bewilderment, and even horror, the student spied a single drop of blood on her white skin within her torn dress. The woman brought out a jar of whisky, put a rusty old kettle on the fire, and took her place in front of it. As soon as the water boiled, she proceeded to make some toddy in a wooden bowl.

Meantime the youth could not take his eyes off the young woman, so that at length he found himself fascinated, or rather bewitched. She kept her eyes for the most part veiled with the loveliest eyelids fringed with darkest lashes, and he gazed entranced; for the red glow of the little oil-lamp covered all the strangeness of her complexion. But as soon as he met a stolen glance out of those eyes unveiled, his soul shuddered within him. Lovely face and craving eyes alternated fascination and repulsion.

The mother placed the bowl in his hands. He drank sparingly, and passed it to the girl. She lifted it to her lips, and as she tasted--only tasted it--looked at him. He thought the drink must have been drugged and have affected his brain. Her hair smoothed itself back, and drew her forehead backwards with it; while the lower part of her face projected towards the bowl, revealing, ere she sipped, her dazzling teeth in strange prominence. But the same moment the vision vanished; she returned the vessel to her mother, and rising, hurried out of the cottage.

Then the old woman pointed to a bed of heather in one corner with a murmured apology; and the student, wearied both with the fatigues of the day and the strangeness of the night, threw himself upon it, wrapped in his cloak. The moment he lay down, the storm began afresh, and the wind blew so keenly through the crannies of the hut, that it was only by drawing his cloak over his head that he could protect himself from its currents. Unable to sleep, he lay listening to the uproar which grew in violence, till the spray was dashing against the window. At length the door opened, and the young woman came in, made up the fire, drew the bench before it, and lay down in the same strange posture, with her chin propped on her hand and elbow, and her face turned towards the youth. He moved a little; she dropped her head, and lay on her face, with her arms crossed beneath her forehead. The mother had disappeared.

Drowsiness crept over him. A movement of the bench roused him, and he fancied he saw some four-footed creature as tall as a large dog trot quietly out of the door. He was sure he felt a rush of cold wind. Gazing fixedly through the darkness, he thought he saw the eyes of the damsel encountering his, but a glow from the falling together of the remnants of the fire revealed clearly enough that the bench was vacant. Wondering what could have made her go out in such a storm, he fell fast asleep.

In the middle of the night he felt a pain in his shoulder, came broad awake, and saw the gleaming eyes and grinning teeth of some animal close to his face. Its claws were in his shoulder, and its mouth in the act of seeking his throat. Before it had fixed its fangs, however, he had its throat in one hand, and sought his knife with the other. A terrible struggle followed; but regardless of the tearing claws, he found and opened his knife. He had made one futile stab, and was drawing it for a surer, when, with a spring of the whole body, and one wildly contorted effort, the creature twisted its neck from his hold, and with something betwixt a scream and a howl, darted from him. Again he heard the door open; again the wind blew in upon him, and it continued blowing; a sheet of spray dashed across the floor, and over his face. He sprung from his couch and bounded to the door.

It was a wild night--dark, but for the flash of whiteness from the waves as they broke within a few yards of the cottage; the wind was raving, and the rain pouring down the air. A gruesome sound as of mingled weeping and howling came from somewhere in the dark. He turned again into the hut and closed the door, but could find no way of securing it.

The lamp was nearly out, and he could not be certain whether the form of the young woman was upon the bench or not. Overcoming a strong repugnance, he approached it, and put out his hands--there was nothing there. He sat down and waited for the daylight: he dared not sleep any more.

When the day dawned at length, he went out yet again, and looked around. The morning was dim and gusty and gray. The wind had fallen, but the waves were tossing wildly. He wandered up and down the little strand, longing for more light.

At length he heard a movement in the cottage. By and by the voice of the old woman called to him from the door.

"You're up early, sir. I doubt you didn't sleep well."

"Not very well," he answered. "But where is your daughter?"

"She's not awake yet," said the mother. "I'm afraid I have but a poor breakfast for you. But you'll take a dram and a bit of fish. It's all I've got."

Unwilling to hurt her, though hardly in good appetite, he sat down at the table. While they were eating, the daughter came in, but turned her face away and went to the farther end of the hut. When she came forward after a minute or two, the youth saw that her hair was drenched, and her face whiter than before. She looked ill and faint, and when she raised her eyes, all their fierceness had vanished, and sadness had taken its place. Her neck was now covered with a cotton handkerchief. She was modestly attentive to him, and no longer shunned his gaze. He was gradually yielding to the temptation of braving another night in the hut, and seeing what would follow, when the old woman spoke.

"The weather will be broken all day, sir," she said. "You had better be going, or your friends will leave without you."

Ere he could answer, he saw such a beseeching glance on the face of the girl, that he hesitated, confused. Glancing at the mother, he saw the flash of wrath in her face. She rose and approached her daughter, with her hand lifted to strike her. The young woman stooped her head with a cry. He darted round the table to interpose between them. But the mother had caught hold of her; the handkerchief had fallen from her neck; and the youth saw five blue bruises on her lovely throat--the marks of the four fingers and the thumb of a left hand. With a cry of horror he darted from the house, but as he reached the door he turned. His hostess was lying motionless on the floor, and a huge gray wolf came bounding after him.

There was no weapon at hand; and if there had been, his inborn chivalry would never have allowed him to harm a woman even under the guise of a wolf. Instinctively, he set himself firm, leaning a little forward, with half outstretched arms, and hands curved ready to clutch again at the throat upon which he had left those pitiful marks. But the creature as she sprung eluded his grasp, and just as he expected to feel her fangs, he found a woman weeping on his bosom, with her arms around his neck. The next instant, the gray wolf broke from him, and bounded howling up the cliff. Recovering himself as he best might, the youth followed, for it was the only way to the moor above, across which he must now make his way to find his companions.

All at once he heard the sound of a crunching of bones--not as if a creature was eating them, but as if they were ground by the teeth of rage and disappointment; looking up, he saw close above him the mouth of the little cavern in which he had taken refuge the day before. Summoning all his resolution, he passed it slowly and softly. From within came the sounds of a mingled moaning and growling.

Having reached the top, he ran at full speed for some distance across the moor before venturing to look behind him. When at length he did so, he saw, against the sky, the girl standing on the edge of the cliff, wringing her hands. One solitary wail crossed the space between. She made no attempt to follow him, and he reached the opposite shore in safety.

The Gray Wolf

by George MacDonald

One evening-twilight in spring, a young English student, who had wandered northwards as far as the outlying fragments of Scotland called the Orkney and Shetland Islands, found himself on a small island of the latter group, caught in a storm of wind and hail, which had come on suddenly. It was in vain to look about for any shelter; for not only did the storm entirely obscure the landscape, but there was nothing around him save a desert moss.

At length, however, as he walked on for mere walking's sake, he found himself on the verge of a cliff, and saw, over the brow of it, a few feet below him, a ledge of rock, where he might find some shelter from the blast, which blew from behind. Letting himself down by his hands, he alighted upon something that crunched beneath his tread, and found the bones of many small animals scattered about in front of a little cave in the rock, offering the refuge he sought. He went in, and sat upon a stone. The storm increased in violence, and as the darkness grew he became uneasy, for he did not relish the thought of spending the night in the cave. He had parted from his companions on the opposite side of the island, and it added to his uneasiness that they must be full of apprehension about him. At last there came a lull in the storm, and the same instant he heard a footfall, stealthy and light as that of a wild beast, upon the bones at the mouth of the cave. He started up in some fear, though the least thought might have satisfied him that there could be no very dangerous animals upon the island. Before he had time to think, however, the face of a woman appeared in the opening. Eagerly the wanderer spoke. She started at the sound of his voice. He could not see her well, because she was turned towards the darkness of the cave.

"Will you tell me how to find my way across the moor to Shielness?" he asked.

"You cannot find it to-night," she answered, in a sweet tone, and with a smile that bewitched him, revealing the whitest of teeth.

"What am I to do, then?"

"My mother will give you shelter, but that is all she has to offer."

"And that is far more than I expected a minute ago," he replied. "I shall be most grateful."

She turned in silence and left the cave. The youth followed.

She was barefooted, and her pretty brown feet went catlike over the sharp stones, as she led the way down a rocky path to the shore. Her garments were scanty and torn, and her hair blew tangled in the wind. She seemed about five and twenty, lithe and small. Her long fingers kept clutching and pulling nervously at her skirts as she went. Her face was very gray in complexion, and very worn, but delicately formed, and smooth-skinned. Her thin nostrils were tremulous as eyelids, and her lips, whose curves were faultless, had no colour to give sign of indwelling blood. What her eyes were like he could not see, for she had never lifted the delicate films of her eyelids.

At the foot of the cliff, they came upon a little hut leaning against it, and having for its inner apartment a natural hollow within. Smoke was spreading over the face of the rock, and the grateful odour of food gave hope to the hungry student. His guide opened the door of the cottage; he followed her in, and saw a woman bending over a fire in the middle of the floor. On the fire lay a large fish broiling. The daughter spoke a few words, and the mother turned and welcomed the stranger. She had an old and very wrinkled, but honest face, and looked troubled. She dusted the only chair in the cottage, and placed it for him by the side of the fire, opposite the one window, whence he saw a little patch of yellow sand over which the spent waves spread themselves out listlessly. Under this window there was a bench, upon which the daughter threw herself in an unusual posture, resting her chin upon her hand. A moment after, the youth caught the first glimpse of her blue eyes. They were fixed upon him with a strange look of greed, amounting to craving, but, as if aware that they belied or betrayed her, she dropped them instantly. The moment she veiled them, her face, notwithstanding its colourless complexion, was almost beautiful.

When the fish was ready, the old woman wiped the deal table, steadied it upon the uneven floor, and covered it with a piece of fine table-linen. She then laid the fish on a wooden platter, and invited the guest to help himself. Seeing no other provision, he pulled from his pocket a hunting knife, and divided a portion from the fish, offering it to the mother first.

"Come, my lamb," said the old woman; and the daughter approached the table. But her nostrils and mouth quivered with disgust.

The next moment she turned and hurried from the hut.

"She doesn't like fish," said the old woman, "and I haven't anything else to give her."

"She does not seem in good health," he rejoined.

The woman answered only with a sigh, and they ate their fish with the help of a little rye bread. As they finished their supper, the youth heard the sound as of the pattering of a dog's feet upon the sand close to the door; but ere he had time to look out of the window, the door opened, and the young woman entered. She looked better, perhaps from having just washed her face. She drew a stool to the corner of the fire opposite him. But as she sat down, to his bewilderment, and even horror, the student spied a single drop of blood on her white skin within her torn dress. The woman brought out a jar of whisky, put a rusty old kettle on the fire, and took her place in front of it. As soon as the water boiled, she proceeded to make some toddy in a wooden bowl.

Meantime the youth could not take his eyes off the young woman, so that at length he found himself fascinated, or rather bewitched. She kept her eyes for the most part veiled with the loveliest eyelids fringed with darkest lashes, and he gazed entranced; for the red glow of the little oil-lamp covered all the strangeness of her complexion. But as soon as he met a stolen glance out of those eyes unveiled, his soul shuddered within him. Lovely face and craving eyes alternated fascination and repulsion.

The mother placed the bowl in his hands. He drank sparingly, and passed it to the girl. She lifted it to her lips, and as she tasted--only tasted it--looked at him. He thought the drink must have been drugged and have affected his brain. Her hair smoothed itself back, and drew her forehead backwards with it; while the lower part of her face projected towards the bowl, revealing, ere she sipped, her dazzling teeth in strange prominence. But the same moment the vision vanished; she returned the vessel to her mother, and rising, hurried out of the cottage.

Then the old woman pointed to a bed of heather in one corner with a murmured apology; and the student, wearied both with the fatigues of the day and the strangeness of the night, threw himself upon it, wrapped in his cloak. The moment he lay down, the storm began afresh, and the wind blew so keenly through the crannies of the hut, that it was only by drawing his cloak over his head that he could protect himself from its currents. Unable to sleep, he lay listening to the uproar which grew in violence, till the spray was dashing against the window. At length the door opened, and the young woman came in, made up the fire, drew the bench before it, and lay down in the same strange posture, with her chin propped on her hand and elbow, and her face turned towards the youth. He moved a little; she dropped her head, and lay on her face, with her arms crossed beneath her forehead. The mother had disappeared.

Drowsiness crept over him. A movement of the bench roused him, and he fancied he saw some four-footed creature as tall as a large dog trot quietly out of the door. He was sure he felt a rush of cold wind. Gazing fixedly through the darkness, he thought he saw the eyes of the damsel encountering his, but a glow from the falling together of the remnants of the fire revealed clearly enough that the bench was vacant. Wondering what could have made her go out in such a storm, he fell fast asleep.

In the middle of the night he felt a pain in his shoulder, came broad awake, and saw the gleaming eyes and grinning teeth of some animal close to his face. Its claws were in his shoulder, and its mouth in the act of seeking his throat. Before it had fixed its fangs, however, he had its throat in one hand, and sought his knife with the other. A terrible struggle followed; but regardless of the tearing claws, he found and opened his knife. He had made one futile stab, and was drawing it for a surer, when, with a spring of the whole body, and one wildly contorted effort, the creature twisted its neck from his hold, and with something betwixt a scream and a howl, darted from him. Again he heard the door open; again the wind blew in upon him, and it continued blowing; a sheet of spray dashed across the floor, and over his face. He sprung from his couch and bounded to the door.

It was a wild night--dark, but for the flash of whiteness from the waves as they broke within a few yards of the cottage; the wind was raving, and the rain pouring down the air. A gruesome sound as of mingled weeping and howling came from somewhere in the dark. He turned again into the hut and closed the door, but could find no way of securing it.

The lamp was nearly out, and he could not be certain whether the form of the young woman was upon the bench or not. Overcoming a strong repugnance, he approached it, and put out his hands--there was nothing there. He sat down and waited for the daylight: he dared not sleep any more.

When the day dawned at length, he went out yet again, and looked around. The morning was dim and gusty and gray. The wind had fallen, but the waves were tossing wildly. He wandered up and down the little strand, longing for more light.

At length he heard a movement in the cottage. By and by the voice of the old woman called to him from the door.

"You're up early, sir. I doubt you didn't sleep well."

"Not very well," he answered. "But where is your daughter?"

"She's not awake yet," said the mother. "I'm afraid I have but a poor breakfast for you. But you'll take a dram and a bit of fish. It's all I've got."

Unwilling to hurt her, though hardly in good appetite, he sat down at the table. While they were eating, the daughter came in, but turned her face away and went to the farther end of the hut. When she came forward after a minute or two, the youth saw that her hair was drenched, and her face whiter than before. She looked ill and faint, and when she raised her eyes, all their fierceness had vanished, and sadness had taken its place. Her neck was now covered with a cotton handkerchief. She was modestly attentive to him, and no longer shunned his gaze. He was gradually yielding to the temptation of braving another night in the hut, and seeing what would follow, when the old woman spoke.

"The weather will be broken all day, sir," she said. "You had better be going, or your friends will leave without you."

Ere he could answer, he saw such a beseeching glance on the face of the girl, that he hesitated, confused. Glancing at the mother, he saw the flash of wrath in her face. She rose and approached her daughter, with her hand lifted to strike her. The young woman stooped her head with a cry. He darted round the table to interpose between them. But the mother had caught hold of her; the handkerchief had fallen from her neck; and the youth saw five blue bruises on her lovely throat--the marks of the four fingers and the thumb of a left hand. With a cry of horror he darted from the house, but as he reached the door he turned. His hostess was lying motionless on the floor, and a huge gray wolf came bounding after him.

There was no weapon at hand; and if there had been, his inborn chivalry would never have allowed him to harm a woman even under the guise of a wolf. Instinctively, he set himself firm, leaning a little forward, with half outstretched arms, and hands curved ready to clutch again at the throat upon which he had left those pitiful marks. But the creature as she sprung eluded his grasp, and just as he expected to feel her fangs, he found a woman weeping on his bosom, with her arms around his neck. The next instant, the gray wolf broke from him, and bounded howling up the cliff. Recovering himself as he best might, the youth followed, for it was the only way to the moor above, across which he must now make his way to find his companions.

All at once he heard the sound of a crunching of bones--not as if a creature was eating them, but as if they were ground by the teeth of rage and disappointment; looking up, he saw close above him the mouth of the little cavern in which he had taken refuge the day before. Summoning all his resolution, he passed it slowly and softly. From within came the sounds of a mingled moaning and growling.

Having reached the top, he ran at full speed for some distance across the moor before venturing to look behind him. When at length he did so, he saw, against the sky, the girl standing on the edge of the cliff, wringing her hands. One solitary wail crossed the space between. She made no attempt to follow him, and he reached the opposite shore in safety.

Published on October 01, 2016 09:00

September 3, 2016

The Man-Eating Horse of Lucknow

In the early 1800s, when India was under the rule of the British East India Company, two English observers rode in a buggy through the city of Lucknow. The streets were deserted. Since Lucknow was a populous city and it was broad day, the men couldn’t at first understand where everyone had gone. They saw only a few people in the distance, running away from the street the buggy traveled. Then they came upon a citizen who was not running away. She lay on the street, her face chewed to a pulp, her body so bludgeoned as to lose its human shape, her hair clotted with gore.

The men rode on, passing the closed doors and windows of houses. The next human being they encountered was a young man, also battered and bitten to death. Finally they saw a soldier standing on a roof. He told them the “man-eater of Lucknow” was to blame. This horse, it was reported, had already killed a number of people; his reputation had spread across the region. Now, as they spoke with the soldier, the Englishmen suddenly saw the animal itself—a big bay stallion rushing down the road. In its mouth it shook a dead child.

When it saw the Englishmen’s buggy, it dropped the child and galloped toward them. The horse pulling their buggy so was frightened they could hardly control it, but they managed it well enough to escape into an iron corral. The stallion arrived. They saw that its head was slathered with blood; clots clung to the hair of its jaws. It tried to kick through the fence, its iron shoes ringing against the iron bars, but the men and their horse were safe inside. It gave up this particular quarry. As it trotted away, it passed through an arch where soldiers had set an ambush. They managed to lasso and muzzle the stallion and lead him into a pen.

He was now the property of the king, who immediately made use of him—as entertainment. The king’s men used a mare to lure the stallion into a fenced courtyard. Then they introduced a tiger. The tiger quickly killed the mare, but hesitated to attack the stallion. After some careful stalking, the tiger sprang. The horse was too quick; he ducked his head and neck to miss the killing bite, though the tiger managed to slice the flesh of his haunches before he was kicked away. A second spring brought the same result. This time, however, the stallion’s iron-shod kick broke the tiger’s jaw, and it refused to try again. The attendants allowed it to return to its cage.

The king had not had his fill. He ordered another tiger released into the courtyard. This one had already been fed. It had no interest in the formidable horse and could not be provoked to fight, even when the attendants prodded it with hot pokers. It, too, was allowed to return to its cage.

Now the king ordered three water buffalo brought in. Water buffalo are generally harmless, but when enraged, they can kill people and even tigers. In the courtyard of the king, however, the buffalo weren’t enraged. They seemed merely puzzled. The stallion looked them over for a few moments. He approached and sniffed at one of them. The buffalo stood with their heads together, like dull-witted counselors conferring. The stallion turned his back on them—and kicked. His hind feet pounded the flesh of the nearest buffalo. It seemed merely annoyed, but the king was delighted. He announced that the “man-eater of Lucknow” had earned his life with his courage. After that, the stallion lived as an exhibit at the king’s palace. Visitors to the town stopped to see him. He was kept in a large cage so that he wouldn’t hurt anyone else.

Was this stallion really a man-eater? I doubt it. Horses aren’t designed to eat meat. They will eat it when especially hungry or, it seems, from idle curiosity. One, for example, was spotted eating a chicken. People have even fed them on blood in a misguided belief that this will make them stronger or faster or more aggressive when used in war. What it really makes them is less healthy; their stomachs are built for grasses and other vegetation. It’s far more probable that the “Man-Eater” of Lucknow merely killed people by biting (as well as kicking). Horrified witnesses mistook its intentions. It surely meant to kill, but not to eat.

This kind of aggression is not typical of horses, but it has precedents. Horses readily kill when they feel threatened by, for example, unfamiliar dogs. Another cause of aggression is abuse. In one case, a man who whipped his pony found himself bloodied with kicks and bites. The pony attempted to bite the man on the face—very much as the victims in Lucknow were bitten. In this case, the man escaped before the pony could finish him. No one knows what abuses the Man-Eater of Lucknow may have endured at the hands of humans.

Published on September 03, 2016 09:00

August 6, 2016

Solomon Islands Skink

Its expression looks almost human, doesn't it? The world's largest skink has an unusual social life. It mates for life, and couples form friendships with other couples. In fact, they form little communities in which the adults help each other take care of the young. Sometimes they even adopt orphans. All of this is terribly unusual among reptiles.

This species is also called the monkey-tailed skink because its tail is prehensile. It uses this to help it climb.

Photos by Dee Puett.

Published on August 06, 2016 09:00

July 9, 2016

Goosefish

Mike Beauregard/Creative Commons

Mike Beauregard/Creative CommonsThough I didn't cover it in The Book of Deadly Animals, Edward Ricciuti lists the goosefish as potentially dangerous to people. Its prey includes fish (small sharks, for instance) and birds (ducks and loons, for instance). As seen in the video below, its method is simply to engulf the prey with its immense mouth. Ricciuti also calls it "the world's most repulsive fish." I think it's kind of cute.

The Goose FishHoward Nemerov

On the long shore, lit by the moon

To show them properly alone,

Two lovers suddenly embraced

So that their shadows were as one.

The ordinary night was graced

For them by the swift tide of blood

That silently they took at flood,

And for a little time they prized

Themselves emparadised.

Then, as if shaken by stage-fright

Beneath the hard moon's bony light,

They stood together on the sand

Embarrassed in each other's sight

But still conspiring hand in hand,

Until they saw, there underfoot,

As though the world had found them out,

The goose fish turning up, though dead,

His hugely grinning head.

There in the china light he lay,

Most ancient and corrupt and grey.

They hesitated at his smile,

Wondering what it seemed to say

To lovers who a little while

Before had thought to understand,

By violence upon the sand,

The only way that could be known

To make a world their own.

It was a wide and moony grin

Together peaceful and obscene;

They knew not what he would express,

So finished a comedian

He might mean failure or success,

But took it for an emblem of

Their sudden, new and guilty love

To be observed by, when they kissed,

That rigid optimist.

So he became their patriarch,

Dreadfully mild in the half-dark.

His throat that the sand seemed to choke,

His picket teeth, these left their mark

But never did explain the joke

That so amused him, lying there

While the moon went down to disappear

Along the still and tilted track

That bears the zodiac.

Published on July 09, 2016 09:00

June 11, 2016

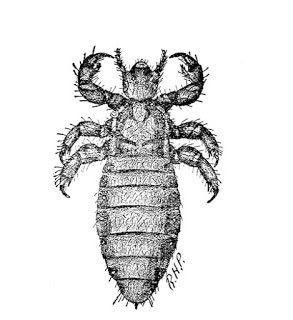

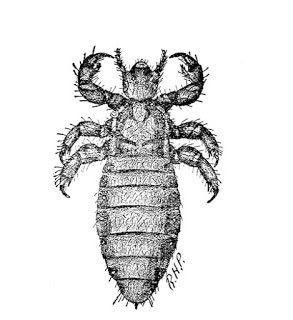

Paintings of Nit-Pickers

In the 17th Century, few Europeans lived without lice. As I mentioned in The Book of Deadly Animals, body lice can spread devastating diseases:

Quirijn van Brekelenkam: Woman Combing Her Child's Hair for Lice

Quirijn van Brekelenkam: Woman Combing Her Child's Hair for Lice

Pieter de Hooch: Mother Delousing Her Child

Pieter de Hooch: Mother Delousing Her Child

Gerhard Ter Borch: Mother Ridding Her Child of Lice

Gerhard Ter Borch: Mother Ridding Her Child of Lice

Gerhard Ter Borch (again): The Family of the Stone-Grinder (notice what the mom's doing).

Gerhard Ter Borch (again): The Family of the Stone-Grinder (notice what the mom's doing).

Bartolome Esteban Murillo: The Toilette

Bartolome Esteban Murillo: The Toilette

Gerhard Ter Borch, one more time. Just for variety, this time it's a kid ridding his dog of fleas, not lice.

Gerhard Ter Borch, one more time. Just for variety, this time it's a kid ridding his dog of fleas, not lice.

(The Flea-Catcher)

But back to the dangerous kind. Below is the poem I mentioned in The Book of Deadly Animals, an eyewitness account of soldiers hassled by lice in the trenches. Isaac Rosenberg was later killed in action at age 27.

Louse Hunting

By Isaac Rosenberg

Nudes—stark and glistening, Yelling in lurid glee. Grinning faces And raging limbs Whirl over the floor on fire. For a shirt verminously busy Yon soldier tore from his throat, with oaths Godhead might shrink at, but not the lice. And soon the shirt was aflare Over the candle he’d lit while we lay.

Then we all sprang up and stript To hunt the verminous brood. Soon like a demons’ pantomime The place was raging. See the silhouettes agape, See the gibbering shadows Mixed with the battled arms on the wall. See gargantuan hooked fingers Pluck in supreme flesh To smutch supreme littleness. See the merry limbs in hot Highland fling Because some wizard vermin Charmed from the quiet this revel When our ears were half lulled By the dark music

Blown from Sleep’s trumpet.

One of the worst disease outbreaks in history was the epidemic typhus that erupted in the trenches during World War I. It begins to torment its victims with a high fever and a headache, proceeds to respiratory symptoms and a rash on the chest, and often goes as far as delirium and death. It killed three million people in Eastern Europe from 1914 to 1915. In fact, this disease has erupted in the wake of wars and natural disasters since the 15th century. By decimating armies, it has determined the outcomes of battles and entire wars, prompting some writers to call the body louse the most important animal in history.A surprising number of paintings show lovers picking lice from each other, or mothers delousing their children. I'll concentrate on paintings of the latter category. The head lice the mothers are after don't share the body louse's habit of spreading disease; they're merely annoyances.

Quirijn van Brekelenkam: Woman Combing Her Child's Hair for Lice

Quirijn van Brekelenkam: Woman Combing Her Child's Hair for Lice Pieter de Hooch: Mother Delousing Her Child

Pieter de Hooch: Mother Delousing Her Child Gerhard Ter Borch: Mother Ridding Her Child of Lice

Gerhard Ter Borch: Mother Ridding Her Child of Lice Gerhard Ter Borch (again): The Family of the Stone-Grinder (notice what the mom's doing).

Gerhard Ter Borch (again): The Family of the Stone-Grinder (notice what the mom's doing). Bartolome Esteban Murillo: The Toilette

Bartolome Esteban Murillo: The Toilette

Gerhard Ter Borch, one more time. Just for variety, this time it's a kid ridding his dog of fleas, not lice.

Gerhard Ter Borch, one more time. Just for variety, this time it's a kid ridding his dog of fleas, not lice. (The Flea-Catcher)

But back to the dangerous kind. Below is the poem I mentioned in The Book of Deadly Animals, an eyewitness account of soldiers hassled by lice in the trenches. Isaac Rosenberg was later killed in action at age 27.

Louse Hunting

By Isaac Rosenberg

Nudes—stark and glistening, Yelling in lurid glee. Grinning faces And raging limbs Whirl over the floor on fire. For a shirt verminously busy Yon soldier tore from his throat, with oaths Godhead might shrink at, but not the lice. And soon the shirt was aflare Over the candle he’d lit while we lay.

Then we all sprang up and stript To hunt the verminous brood. Soon like a demons’ pantomime The place was raging. See the silhouettes agape, See the gibbering shadows Mixed with the battled arms on the wall. See gargantuan hooked fingers Pluck in supreme flesh To smutch supreme littleness. See the merry limbs in hot Highland fling Because some wizard vermin Charmed from the quiet this revel When our ears were half lulled By the dark music

Blown from Sleep’s trumpet.

Published on June 11, 2016 09:00

May 14, 2016

Squirrel Skulls (Warning: Gruesome)

A few years ago I wrote about a certain road-killed squirrel. Parker and I, imitating the great biologist Francesco Redi, took possession of this dainty article and observed it for days. Redi used that sort of observation to prove that dead things don’t actually turn into worms by spontaneous generation. Instead, the worms are insect larvae. If flies and beetles can’t reach the dead animal to lay eggs on it, the worms don’t appear. In that one series of experiments, Redi not only debunked spontaneous generation, he also invented the idea of scientific controls—that is, changing a factor in one experiment while keeping that factor the same in a parallel experiment.

What Parker and I got was no scientific revolution, but a cool set of photos—and a few surprises. We learned about parasites and predators in our back yard that we’d never suspected.

I mention all this because not long ago, Parker made a couple more discoveries. Beneath the shed whose roof held our roadkill for observation, he found the skull and jawbones of another squirrel. At first he suspected this might be exactly the one we observed all those years ago. It isn’t, as I knew because I’d seen this new squirrel turn up dead in the yard one day and placed it there for further observations, which I then forgot to make. (Besides, as my original article reminds me, the first squirrel was removed by a scavenger.)

Parker’s other discovery turned up in the rain barrel. I call it a rain barrel because it was a barrel full of rain. It wasn’t there for that purpose, however. It was simply a trash barrel that Beckett had put there because, one humid day, he found it crawling with gleaming maggots. He hated to leave it near the house, so he tossed it into the yard, far back where he wouldn’t have to look at it. It stood there through several rains. What Parker found in that barrel of rain was squirrel stew. The way I figure it, some squirrel must have fallen in from the pine tree above and found itself unable to climb out. A few weeks converted it to a furry, semi-liquid mess. Parker overturned the barrel and noted, among the gray leavings on the ground, the disarticulated skeleton of the squirrel.

It was all very gruesome, but a few weeks of drying in the garage will convert these fine bones into another specimen for my Cabinet of Curiosities.

Trust me, squirrel bones are hiding in this mess.

Trust me, squirrel bones are hiding in this mess.

Published on May 14, 2016 09:00

April 16, 2016

The Death of Abraham Lincoln

The DEATH OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN by Walt Whitman(condensed)

There were many lilacs in full bloom. By one of those caprices that enter and give tinge to events without being at all a part of them, I find myself always reminded of the great tragedy of that day by the sight and odor of these blossoms. It never fails.

The theatre was crowded, many ladies in rich and gay costumes, officers in their uniforms, many well-known citizens, young folks, the usual clusters of gas-lights, the usual magnetism of so many people, cheerful, with perfumes, music of violins and flutes—(and over all, and saturating all, that vast, vague wonder, Victory, the nation's victory, the triumph of the Union, filling the air, the thought, the sense, with exhilaration more than all music and perfumes.)

The President came betimes, and, with his wife, witness'd the play from the large stage-boxes of the second tier, two thrown into one, and profusely drap'd with the national flag. The acts and scenes of the piece—one of those singularly written compositions which have at least the merit of giving entire relief to an audience engaged in mental action or business excitements and cares during the day, as it makes not the slightest call on either the moral, emotional, esthetic, or spiritual nature—a piece, ("Our American Cousin,") in which, among other characters, so call'd, a Yankee, certainly such a one as was never seen, or the least like it ever seen, in North America, is introduced in England, with a varied fol-de-rol of talk, plot, scenery, and such phantasmagoria as goes to make up a modern popular drama—had progress'd through perhaps a couple of its acts, when in the midst of this comedy, or non-such, or whatever it is to be call'd, and to offset it, or finish it out, as if in Nature's and the great Muse's mockery of those poor mimes, came interpolated that scene, not really or exactly to be described at all, (for on the many hundreds who were there it seems to this hour to have left a passing blur, a dream, a blotch)—and yet partially to be described as I now proceed to give it. There is a scene in the play representing a modern parlor in which two unprecedented English ladies are inform'd by the impossible Yankee that he is not a man of fortune, and therefore undesirable for marriage-catching purposes; after which, the comments being finish'd, the dramatic trio make exit, leaving the stage clear for a moment. At this period came the murder of Abraham Lincoln.

Great as all its manifold train, circling round it, and stretching into the future for many a century, in the politics, history, art, &c., of the New World, in point of fact the main thing, the actual murder, transpired with the quiet and simplicity of any commonest occurrence—the bursting of a bud or pod in the growth of vegetation, for instance. Through the general hum following the stage pause, with the change of positions, came the muffled sound of a pistol-shot, which not one-hundredth part of the audience heard at the time—and yet a moment's hush—somehow, surely, a vague startled thrill—and then, through the ornamented, draperied, starr'd and striped space-way of the President's box, a sudden figure, a man, raises himself with hands and feet, stands a moment on the railing, leaps below to the stage, (a distance of perhaps fourteen or fifteen feet,) falls out of position, catching his boot-heel in the copious drapery, (the American flag,) falls on one knee, quickly recovers himself, rises as if nothing had happen'd, (he really sprains his ankle, but unfelt then)—and so the figure, Booth, the murderer, dress'd in plain black broadcloth, bare-headed, with full, glossy, raven hair, and his eyes like some mad animal's flashing with light and resolution, yet with a certain strange calmness, holds aloft in one hand a large knife—walks along not much back from the footlights—turns fully toward the audience his face of statuesque beauty, lit by those basilisk eyes, flashing with desperation, perhaps insanity—launches out in a firm and steady voice the words Sic semper tyrannis—and then walks with neither slow nor very rapid pace diagonally across to the back of the stage, and disappears. (Had not all this terrible scene—making the mimic ones preposterous—had it not all been rehears'd, in blank, by Booth, beforehand?)

A moment's hush—a scream—the cry of murder—Mrs. Lincoln leaning out of the box, with ashy cheeks and lips, with involuntary cry, pointing to the retreating figure, He has kill'd the President. And still a moment's strange, incredulous suspense—and then the deluge!—then that mixture of horror, noises, uncertainty—(the sound, somewhere back, of a horse's hoofs clattering with speed)—the people burst through chairs and railings, and break them up—there is inextricable confusion and terror—women faint—quite feeble persons fall, and are trampl'd on—many cries of agony are heard—the broad stage suddenly fills to suffocation with a dense and motley crowd, like some horrible carnival—the audience rush generally upon it, at least the strong men do—the actors and actresses are all there in their play-costumes and painted faces, with mortal fright showing through the rouge—the screams and calls, confused talk—redoubled, trebled—two or three manage to pass up water from the stage to the President's box—others try to clamber up.

In the midst of all this, the soldiers of the President's guard, with others, suddenly drawn to the scene, burst in—(some two hundred altogether)—they storm the house, through all the tiers, especially the upper ones, inflam'd with fury, literally charging the audience with fix'd bayonets, muskets and pistols, shouting “Clear out! clear out! you sons of bitches.”

Outside, too, in the atmosphere of shock and craze, crowds of people, fill'd with frenzy, ready to seize any outlet for it, come near committing murder several times on innocent individuals. One such case was especially exciting. The infuriated crowd, through some chance, got started against one man, either for words he utter'd, or perhaps without any cause at all, and were proceeding at once to actually hang him on a neighboring lamp-post, when he was rescued by a few heroic policemen, who placed him in their midst, and fought their way slowly and amid great peril toward the station house. It was a fitting episode of the whole affair. The crowd rushing and eddying to and fro—the night, the yells, the pale faces, many frighten'd people trying in vain to extricate themselves—the attack'd man, not yet freed from the jaws of death, looking like a corpse—the silent, resolute, half-dozen policemen, with no weapons but their little clubs, yet stern and steady through all those eddying swarms—made a fitting side-scene to the grand tragedy of the murder. They gain'd the station house with the protected man, whom they placed in security for the night, and discharged him in the morning.

And in the midst of that pandemonium, infuriated soldiers, the audience and the crowd, the stage, and all its actors and actresses, its paint-pots, spangles, and gas-lights—the life blood from those veins, the best and sweetest of the land, drips slowly down, and death's ooze already begins its little bubbles on the lips.

Published on April 16, 2016 00:00