Jonah Lehrer's Blog, page 2

July 14, 2010

Smart Babies

Over at Sciam’s Mind Matters, Melody Dye has a great post on the surprising advantages of thinking like a baby. At first glance, this might seem like a ridiculous conjecture: A baby, after all, is missing most of the capabilities that define the human mind, such as language and the ability to reason or focus. Rene Descartes argued that the young child was entirely bound by sensation, hopelessly trapped in the confusing rush of the here and now. A newborn, in this sense, is just a lump of need, a bundle of reflexes that can only eat and cry. To think like a baby is to not think at all.

And yet, Dye notes that the very neural features that make babies so babyish might also allow them to learn about the world at an accelerated rate. Consider, for instance, the lack of a prefrontal cortex (PFC), which is woefully underdeveloped in infants. (Your PFC isn’t fully developed until late adolescence.) One of the main consequences of not having an online PFC is that babies can’t focus their attention. Alison Gopnik, a UC-Berkeley psychologist who has written a few wonderful books on baby cognition, suggests the following metaphor: If attention works like a narrow spotlight in adults – a focused beam illuminating particular parts of reality – then in babies it works more like a lantern, casting a diffuse radiance on their surroundings.

The lantern mode of attention can make babies seem very peculiar. For example, when preschoolers are shown a photograph of someone – let’s call her Jane – looking at a picture of a family, they make very different assumptions about Jane’s state of mind. When the young children are asked questions about what Jane is paying attention to, the kids quickly agree that Jane is thinking about the people in the picture. But they also insist that she’s thinking about the picture frame, and the wall behind the picture, and the chair lurking in her peripheral vision. In other words, they believe that Jane is attending to whatever she can see.

While this less focused form of attention makes it more difficult to stay on task – preschoolers are easily distracted – it also comes with certain advantages. In many circumstances, the lantern mode of attention can actually lead to improvements in memory, especially when it comes to recalling information that seemed incidental at the time. This suggests that the so-called deficits of the baby brain are actually advantages, and might be there by design. Here’s Dye:

The superiority of children’s convention learning has been revealed in a series of ingenious studies by psychologists Carla Hudson-Kam and Elissa Newport, who tested how children and adults react to variable and inconsistent input when learning an artificial language. Strikingly, Hudson-Kam and Newport found that while children tended to ignore “noise” in the input, systematizing any variations they were exposed to, adults did just the opposite, and reproduced the variability they encountered.

So, for example, if subjects heard “elle va à la fac” 60% of the time and “elle va à fac” 40% of the time, adult learners tended to probability match and include “la” about 60% of the time, whereas younger learners tended to maximize and include “la” all of the time. While younger learners found the most consistent patterns in what they heard, and then conventionalized them, the adults simply reproduced what they heard. In William James’ terms, the children made sense of the “blooming, buzzing confusion” they were exposed to in the experiment, whereas the adults did not.

Children’s inability to filter their learning allows them to impose order on variable, inconsistent input, and this appears to play a crucial part in the establishment of stable linguistic norms. Studies of deaf children have shown that even when parental attempts at sign are error-prone and inconsistent, children still extract the conventions of a standard sign language from them. Indeed, the variable patterns produced by parents who learn sign language offers insight into what might happen if children did not maximize in learning: language, as a system, would become less conventional. What words meant and the patterns in which they were used would become more idiosyncratic and unstable, and all languages would begin to resemble pidgins.

Or consider this experiment, designed by John Hagen, a developmental psychologist at the University of Michigan. A child is given a deck of cards and shown two cards at a time. The child is told to remember the card on the right and to ignore the card on the left. Not surprisingly, older children and adults are much better at remembering the cards they were told to focus on, since they’re able to direct their attention. However, young children are often better at remembering the cards on the left, which they were supposed to ignore. The lantern casts its light everywhere.

And it’s not just complex learning that benefits from a quiet PFC. A recent brain scanning experiment by researchers at Johns Hopkins University found that jazz musicians in the midst of improvisation – they were playing a specially designed keyboard in a brain scanner – showed dramatically reduced activity in a part of the prefrontal cortex. It was only by “deactivating” this brain area – inhibiting their inhibitions, so to speak – that the musicians were able to spontaneously invent new melodies. The scientists compare this unwound state of mind with that of dreaming during REM sleep, meditation, and other creative pursuits, such as the composition of poetry. But it also resembles the thought process of a young child, albeit one with musical talent. Baudelaire was right: “Genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.”

Smart Babies

Over at Sciam's Mind Matters, Melody Dye has a great post on the surprising advantages of thinking like a baby. At first glance, this might seem like a ridiculous conjecture: A baby, after all, is missing most of the capabilities that define the human mind, such as language and the ability to reason or focus. Rene Descartes argued that the young child was entirely bound by sensation, hopelessly trapped in the confusing rush of the here and now. A newborn, in this sense, is just a lump of need, a bundle of reflexes that can only eat and cry. To think like a baby is to not think at all.

And yet, Dye notes that the very neural features that make babies so babyish might also allow them to learn about the world at an accelerated rate. Consider, for instance, the lack of a prefrontal cortex (PFC), which is woefully underdeveloped in infants. (Your PFC isn't fully developed until late adolescence.) One of the main consequences of not having an online PFC is that babies can't focus their attention. Alison Gopnik, a UC-Berkeley psychologist who has written a few wonderful books on baby cognition, suggests the following metaphor: If attention works like a narrow spotlight in adults - a focused beam illuminating particular parts of reality - then in babies it works more like a lantern, casting a diffuse radiance on their surroundings.

The lantern mode of attention can make babies seem very peculiar. For example, when preschoolers are shown a photograph of someone - let's call her Jane - looking at a picture of a family, they make very different assumptions about Jane's state of mind. When the young children are asked questions about what Jane is paying attention to, the kids quickly agree that Jane is thinking about the people in the picture. But they also insist that she's thinking about the picture frame, and the wall behind the picture, and the chair lurking in her peripheral vision. In other words, they believe that Jane is attending to whatever she can see.

While this less focused form of attention makes it more difficult to stay on task - preschoolers are easily distracted - it also comes with certain advantages. In many circumstances, the lantern mode of attention can actually lead to improvements in memory, especially when it comes to recalling information that seemed incidental at the time. This suggests that the so-called deficits of the baby brain are actually advantages, and might be there by design. Here's Dye:

The superiority of children's convention learning has been revealed in a series of ingenious studies by psychologists Carla Hudson-Kam and Elissa Newport, who tested how children and adults react to variable and inconsistent input when learning an artificial language. Strikingly, Hudson-Kam and Newport found that while children tended to ignore "noise" in the input, systematizing any variations they were exposed to, adults did just the opposite, and reproduced the variability they encountered.

So, for example, if subjects heard "elle va à la fac" 60% of the time and "elle va à fac" 40% of the time, adult learners tended to probability match and include "la" about 60% of the time, whereas younger learners tended to maximize and include "la" all of the time. While younger learners found the most consistent patterns in what they heard, and then conventionalized them, the adults simply reproduced what they heard. In William James' terms, the children made sense of the "blooming, buzzing confusion" they were exposed to in the experiment, whereas the adults did not.

Children's inability to filter their learning allows them to impose order on variable, inconsistent input, and this appears to play a crucial part in the establishment of stable linguistic norms. Studies of deaf children have shown that even when parental attempts at sign are error-prone and inconsistent, children still extract the conventions of a standard sign language from them. Indeed, the variable patterns produced by parents who learn sign language offers insight into what might happen if children did not maximize in learning: language, as a system, would become less conventional. What words meant and the patterns in which they were used would become more idiosyncratic and unstable, and all languages would begin to resemble pidgins.

Or consider this experiment, designed by John Hagen, a developmental psychologist at the University of Michigan. A child is given a deck of cards and shown two cards at a time. The child is told to remember the card on the right and to ignore the card on the left. Not surprisingly, older children and adults are much better at remembering the cards they were told to focus on, since they're able to direct their attention. However, young children are often better at remembering the cards on the left, which they were supposed to ignore. The lantern casts its light everywhere.

And it's not just complex learning that benefits from a quiet PFC. A recent brain scanning experiment by researchers at Johns Hopkins University found that jazz musicians in the midst of improvisation - they were playing a specially designed keyboard in a brain scanner - showed dramatically reduced activity in a part of the prefrontal cortex. It was only by "deactivating" this brain area - inhibiting their inhibitions, so to speak - that the musicians were able to spontaneously invent new melodies. The scientists compare this unwound state of mind with that of dreaming during REM sleep, meditation, and other creative pursuits, such as the composition of poetry. But it also resembles the thought process of a young child, albeit one with musical talent. Baudelaire was right: "Genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will."

cortex

Wed, 07/14/2010 - 13:36

July 13, 2010

Political Dissonance

Joe Keohane has a fascinating summary of our political biases in the Boston Globe Ideas section this weekend. It's probably not surprising that voters aren't rational agents, but it's always a little depressing to realize just how irrational we are. (And it's worth pointing out that this irrationality applies to both sides of the political spectrum.) We cling to mistaken beliefs and ignore salient facts. We cherry-pick our information and vote for people based on an inexplicable stew of...

Political Dissonance

Joe Keohane has a fascinating summary of our political biases in the Boston Globe Ideas section this weekend. It’s probably not surprising that voters aren’t rational agents, but it’s always a little depressing to realize just how irrational we are. (And it’s worth pointing out that this irrationality applies to both sides of the political spectrum.) We cling to mistaken beliefs and ignore salient facts. We cherry-pick our information and vote for people based on an inexplicable stew of superficial hunches, stubborn ideologies and cultural trends. From the perspective of the human brain, it’s a miracle that democracy works at all. Here’s Keohane:

A striking recent example was a study done in the year 2000, led by James Kuklinski of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He led an influential experiment in which more than 1,000 Illinois residents were asked questions about welfare — the percentage of the federal budget spent on welfare, the number of people enrolled in the program, the percentage of enrollees who are black, and the average payout. More than half indicated that they were confident that their answers were correct — but in fact only 3 percent of the people got more than half of the questions right. Perhaps more disturbingly, the ones who were the most confident they were right were by and large the ones who knew the least about the topic. (Most of these participants expressed views that suggested a strong antiwelfare bias.)

Studies by other researchers have observed similar phenomena when addressing education, health care reform, immigration, affirmative action, gun control, and other issues that tend to attract strong partisan opinion. Kuklinski calls this sort of response the “I know I’m right” syndrome, and considers it a “potentially formidable problem” in a democratic system. “It implies not only that most people will resist correcting their factual beliefs,” he wrote, “but also that the very people who most need to correct them will be least likely to do so.”

In How We Decide, I discuss the mental mechanisms behind these flaws, which are ultimately rooted in cognitive dissonance:

Partisan voters are convinced that they’re rational⎯only the other side is irrational⎯but we’re actually rationalizers. The Princeton political scientist Larry Bartels analyzed survey data from the 1990′s to prove this point. During the first term of Bill Clinton’s presidency, the budget deficit declined by more than 90 percent. However, when Republican voters were asked in 1996 what happened to the deficit under Clinton, more than 55 percent said that it had increased. What’s interesting about this data is that so-called “high-information” voters⎯these are the Republicans who read the newspaper, watch cable news and can identify their representatives in Congress⎯weren’t better informed than “low-information” voters. According to Bartels, the reason knowing more about politics doesn’t erase partisan bias is that voters tend to only assimilate those facts that confirm what they already believe. If a piece of information doesn’t follow Republican talking points⎯and Clinton’s deficit reduction didn’t fit the “tax and spend liberal” stereotype⎯then the information is conveniently ignored. “Voters think that they’re thinking,” Bartels says, “but what they’re really doing is inventing facts or ignoring facts so that they can rationalize decisions they’ve already made.” Once we identify with a political party, the world is edited so that it fits with our ideology.

At such moments, rationality actually becomes a liability, since it allows us to justify practically any belief. We use the our fancy brain as an information filter, a way to block-out disagreeable points of view. Consider this experiment, which was done in the late 1960′s, by the cognitive psychologists Timothy Brock and Joe Balloun. They played a group of people a tape-recorded message attacking Christianity. Half of the subjects were regular churchgoers while the other half were committed atheists. To make the experiment more interesting, Brock and Balloun added an annoying amount of static⎯a crackle of white noise⎯to the recording. However, they allowed listeners to reduce the static by pressing a button, so that the message suddenly became easier to understand. Their results were utterly predicable and rather depressing: the non-believers always tried to remove the static, while the religious subjects actually preferred the message that was harder to hear. Later experiments by Brock and Balloun demonstrated a similar effect with smokers listening to a speech on the link between smoking and cancer. We silence the cognitive dissonance through self-imposed ignorance.

There is no cure for this ideological irrationality – it’s simply the way we’re built. Nevertheless, I think a few simple fixes could dramatically improve our political culture. We should begin by minimizing our exposure to political pundits. The problem with pundits is best illustrated by the classic work of Philip Tetlock, a psychologist at UC-Berkeley. (I’ve written about this before on this blog.) Starting in the early 1980s, Tetlock picked two hundred and eighty-four people who made their living “commenting or offering advice on political and economic trends” and began asking them to make predictions about future events. He had a long list of questions. Would George Bush be re-elected? Would there be a peaceful end to apartheid in South Africa? Would Quebec secede from Canada? Would the dot-com bubble burst? In each case, the pundits were asked to rate the probability of several possible outcomes. Tetlock then interrogated the pundits about their thought process, so that he could better understand how they made up their minds. By the end of the study, Tetlock had quantified 82,361 different predictions.

After Tetlock tallied up the data, the predictive failures of the pundits became obvious. Although they were paid for their keen insights into world affairs, they tended to perform worse than random chance. Most of Tetlock’s questions had three possible answers; the pundits, on average, selected the right answer less than 33 percent of the time. In other words, a dart-throwing chimp would have beaten the vast majority of professionals.

So those talking heads on television are full of shit. Probably not surprising. What’s much more troubling, however, is that they’ve become our model of political discourse. We now associate political interest with partisan blowhards on cable TV, these pundits and consultants and former politicians who trade facile talking points. Instead of engaging with contrary facts, the discourse has become one big study in cognitive dissonance. And this is why the predictions of pundits are so consistently inaccurate. Unless we engage with those uncomfortable data points, those stats which suggest that George W. Bush wasn’t all bad, or that Obama isn’t such a leftist radical, then our beliefs will never improve. (It doesn’t help, of course, that our news sources are increasingly segregated along ideological lines.) So here’s my theorem: The value of a political pundit is directly correlated with his or her willingness to admit past error. And when was the last time you heard Karl Rove admit that he was wrong?

Political Dissonance

Joe Keohane has a fascinating summary of our political biases in the Boston Globe Ideas section this weekend. It's probably not surprising that voters aren't rational agents, but it's always a little depressing to realize just how irrational we are. (And it's worth pointing out that this irrationality applies to both sides of the political spectrum.) We cling to mistaken beliefs and ignore salient facts. We cherry-pick our information and vote for people based on an inexplicable stew of superficial hunches, stubborn ideologies and cultural trends. From the perspective of the human brain, it's a miracle that democracy works at all. Here's Keohane:

A striking recent example was a study done in the year 2000, led by James Kuklinski of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He led an influential experiment in which more than 1,000 Illinois residents were asked questions about welfare -- the percentage of the federal budget spent on welfare, the number of people enrolled in the program, the percentage of enrollees who are black, and the average payout. More than half indicated that they were confident that their answers were correct -- but in fact only 3 percent of the people got more than half of the questions right. Perhaps more disturbingly, the ones who were the most confident they were right were by and large the ones who knew the least about the topic. (Most of these participants expressed views that suggested a strong antiwelfare bias.)

Studies by other researchers have observed similar phenomena when addressing education, health care reform, immigration, affirmative action, gun control, and other issues that tend to attract strong partisan opinion. Kuklinski calls this sort of response the "I know I'm right" syndrome, and considers it a "potentially formidable problem" in a democratic system. "It implies not only that most people will resist correcting their factual beliefs," he wrote, "but also that the very people who most need to correct them will be least likely to do so."

In How We Decide, I discuss the mental mechanisms behind these flaws, which are ultimately rooted in cognitive dissonance:

Partisan voters are convinced that they're rationalâ¯only the other side is irrationalâ¯but we're actually rationalizers. The Princeton political scientist Larry Bartels analyzed survey data from the 1990's to prove this point. During the first term of Bill Clinton's presidency, the budget deficit declined by more than 90 percent. However, when Republican voters were asked in 1996 what happened to the deficit under Clinton, more than 55 percent said that it had increased. What's interesting about this data is that so-called "high-information" votersâ¯these are the Republicans who read the newspaper, watch cable news and can identify their representatives in Congressâ¯weren't better informed than "low-information" voters. According to Bartels, the reason knowing more about politics doesn't erase partisan bias is that voters tend to only assimilate those facts that confirm what they already believe. If a piece of information doesn't follow Republican talking pointsâ¯and Clinton's deficit reduction didn't fit the "tax and spend liberal" stereotypeâ¯then the information is conveniently ignored. "Voters think that they're thinking," Bartels says, "but what they're really doing is inventing facts or ignoring facts so that they can rationalize decisions they've already made." Once we identify with a political party, the world is edited so that it fits with our ideology.

At such moments, rationality actually becomes a liability, since it allows us to justify practically any belief. We use the our fancy brain as an information filter, a way to block-out disagreeable points of view. Consider this experiment, which was done in the late 1960's, by the cognitive psychologists Timothy Brock and Joe Balloun. They played a group of people a tape-recorded message attacking Christianity. Half of the subjects were regular churchgoers while the other half were committed atheists. To make the experiment more interesting, Brock and Balloun added an annoying amount of staticâ¯a crackle of white noiseâ¯to the recording. However, they allowed listeners to reduce the static by pressing a button, so that the message suddenly became easier to understand. Their results were utterly predicable and rather depressing: the non-believers always tried to remove the static, while the religious subjects actually preferred the message that was harder to hear. Later experiments by Brock and Balloun demonstrated a similar effect with smokers listening to a speech on the link between smoking and cancer. We silence the cognitive dissonance through self-imposed ignorance.

There is no cure for this ideological irrationality - it's simply the way we're built. Nevertheless, I think a few simple fixes could dramatically improve our political culture. We should begin by minimizing our exposure to political pundits. The problem with pundits is best illustrated by the classic work of Philip Tetlock, a psychologist at UC-Berkeley. (I've written about this before on this blog.) Starting in the early 1980s, Tetlock picked two hundred and eighty-four people who made their living "commenting or offering advice on political and economic trends" and began asking them to make predictions about future events. He had a long list of questions. Would George Bush be re-elected? Would there be a peaceful end to apartheid in South Africa? Would Quebec secede from Canada? Would the dot-com bubble burst? In each case, the pundits were asked to rate the probability of several possible outcomes. Tetlock then interrogated the pundits about their thought process, so that he could better understand how they made up their minds. By the end of the study, Tetlock had quantified 82,361 different predictions.

After Tetlock tallied up the data, the predictive failures of the pundits became obvious. Although they were paid for their keen insights into world affairs, they tended to perform worse than random chance. Most of Tetlock's questions had three possible answers; the pundits, on average, selected the right answer less than 33 percent of the time. In other words, a dart-throwing chimp would have beaten the vast majority of professionals.

So those talking heads on television are full of shit. Probably not surprising. What's much more troubling, however, is that they've become our model of political discourse. We now associate political interest with partisan blowhards on cable TV, these pundits and consultants and former politicians who trade facile talking points. Instead of engaging with contrary facts, the discourse has become one big study in cognitive dissonance. And this is why the predictions of pundits are so consistently inaccurate. Unless we engage with those uncomfortable data points, those stats which suggest that George W. Bush wasn't all bad, or that Obama isn't such a leftist radical, then our beliefs will never improve. (It doesn't help, of course, that our news sources are increasingly segregated along ideological lines.) So here's my theorem: The value of a political pundit is directly correlated with his or her willingness to admit past error. And when was the last time you heard Karl Rove admit that he was wrong?

cortex

Tue, 07/13/2010 - 06:57

July 12, 2010

Will I?

We can't help but talk to ourselves. At any given moment, there's a running commentary unfolding in our stream of consciousness, an incessant soliloquy of observations, questions and opinions. But what's the best way to structure all this introspective chatter? What kind of words should we whisper to ourselves? And does all this self-talk even matter?

These are the fascinating questions asked in a new paper led by Ibrahim Senay and Dolores Albarracin, at the University of Illinois at...

Will I?

We can’t help but talk to ourselves. At any given moment, there’s a running commentary unfolding in our stream of consciousness, an incessant soliloquy of observations, questions and opinions. But what’s the best way to structure all this introspective chatter? What kind of words should we whisper to ourselves? And does all this self-talk even matter?

These are the fascinating questions asked in a new paper led by Ibrahim Senay and Dolores Albarracin, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and published in Psychological Science. The experiment was straightforward. Fifty three undergrads were divided into two groups. The first group was told to prepare for an anagram-solving task by thinking, for one minute, about whether they would work on anagrams. This is the “Will I?” condition, which the scientists refer to as the “interrogative form of self-talk”. The second group, in contrast, was told to spend one minute thinking that they would work on anagrams. This is the “I Will” condition, or the “declarative form of self-talk”. Both groups were then given ten minutes to solve as many anagrams as possible.

At first glance, we might assume that the “I Will” group would solve more anagrams. After all, they are committing themselves to the task, silently asserting that they will solve the puzzles. The interrogative group, on the other hand, was just asking themselves a question; there was no commitment, just some inner uncertainty.

But that’s not what happened. It turned out that that the “Will I?” group solved nearly 25 percent more anagrams. When people asked themselves a question – Can I do this? – they became more motivated to actually do it, which allowed them to solve more puzzles. This suggests that the Nike slogan should be “Just do it?” and not “Just do it”.

Why is interrogative self-talk more effective? Subsequent experiments by the scientists suggested that the power of the “Will I?” condition resides in its ability to elicit intrinsic motivation. (We are intrinsically motivated when we are doing an activity for ourselves, because we enjoy it. In contrast, extrinsic motivation occurs when we’re doing something for a paycheck or any “extrinsic” reward.) By interrogating ourselves, we set up a well-defined challenge that we can master. And it is this desire for personal fulfillment – being able to tell ourselves that we solved the anagrams – that actually motivates us to keep on trying. Here is an excerpt from the paper:

Self-posed questions about a future behavior may inspire thoughts about autonomous or intrinsically motivated reasons to pursue a goal, leading to interrogative self-talk and intention forming corresponding intentions and ultimately performing the behavior. In fact, people are more likely to engage in a behavior when they have intrinsic motivation (i.e., when they feel personally responsible for their action) than when they have extrinsic motivation (i.e., when they feel external factors such as other people are responsible for their action) in diverse domains from education to medical treatment to addiction recovery to task performance

Scientists have recognized the importance of intrinsic motivation for decades. In the 1970s, Mark Lepper, David Greene and Richard Nisbett conducted a classic study on preschoolers who liked to draw. They divided the kids into three groups. The first group of kids was told that they’d get a reward – a nice blue ribbon with their name on it – if they continued to draw. The second group wasn’t told about the rewards but was given a blue ribbon after drawing. (This was the “unexpected reward” condition.) Finally, the third group was the “no award” condition. They weren’t even told about the blue ribbons.

After two weeks of reinforcement, the scientists observed the preschoolers during a typical period of free play. Here’s where the results get interesting: The kids in the “no award’ and “unexpected award” conditions kept on drawing with the same enthusiasm as before. Their behavior was unchanged. In contrast, the preschoolers in the “award” group now showed much less interest in the activity. Instead of drawing, they played with blocks, or took a nap, or went outside. The reason was that their intrinsic motivation to draw had been contaminated by blue ribbons; the extrinsic reward had diminished the pleasure of playing with crayons and paper. (Daniel Pink, in his excellent book Drive, refers to this as the “Sawyer Effect”.)

So the next time you’re faced with a difficult task, don’t look at a Nike ad, and don’t think about the extrinsic rewards of success. Instead, ask yourself a simple question: Will I do this? I think I will.

Update: Daniel Pink has more.

Will I?

We can't help but talk to ourselves. At any given moment, there's a running commentary unfolding in our stream of consciousness, an incessant soliloquy of observations, questions and opinions. But what's the best way to structure all this introspective chatter? What kind of words should we whisper to ourselves? And does all this self-talk even matter?

These are the fascinating questions asked in a new paper led by Ibrahim Senay and Dolores Albarracin, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and published in Psychological Science. The experiment was straightforward. Fifty three undergrads were divided into two groups. The first group was told to prepare for an anagram-solving task by thinking, for one minute, about whether they would work on anagrams. This is the "Will I?" condition, which the scientists refer to as the "interrogative form of self-talk". The second group, in contrast, was told to spend one minute thinking that they would work on anagrams. This is the "I Will" condition, or the "declarative form of self-talk". Both groups were then given ten minutes to solve as many anagrams as possible.

At first glance, we might assume that the "I Will" group would solve more anagrams. After all, they are committing themselves to the task, silently asserting that they will solve the puzzles. The interrogative group, on the other hand, was just asking themselves a question; there was no commitment, just some inner uncertainty.

But that's not what happened. It turned out that that the "Will I?" group solved nearly 25 percent more anagrams. When people asked themselves a question - Can I do this? - they became more motivated to actually do it, which allowed them to solve more puzzles. This suggests that the Nike slogan should be "Just do it?" and not "Just do it".

Why is interrogative self-talk more effective? Subsequent experiments by the scientists suggested that the power of the "Will I?" condition resides in its ability to elicit intrinsic motivation. (We are intrinsically motivated when we are doing an activity for ourselves, because we enjoy it. In contrast, extrinsic motivation occurs when we're doing something for a paycheck or any "extrinsic" reward.) By interrogating ourselves, we set up a well-defined challenge that we can master. And it is this desire for personal fulfillment - being able to tell ourselves that we solved the anagrams - that actually motivates us to keep on trying. Here is an excerpt from the paper:

Self-posed questions about a future behavior may inspire thoughts about autonomous or intrinsically motivated reasons to pursue a goal, leading to interrogative self-talk and intention forming corresponding intentions and ultimately performing the behavior. In fact, people are more likely to engage in a behavior when they have intrinsic motivation (i.e., when they feel personally responsible for their action) than when they have extrinsic motivation (i.e., when they feel external factors such as other people are responsible for their action) in diverse domains from education to medical treatment to addiction recovery to task performance

Scientists have recognized the importance of intrinsic motivation for decades. In the 1970s, Mark Lepper, David Greene and Richard Nisbett conducted a classic study on preschoolers who liked to draw. They divided the kids into three groups. The first group of kids was told that they'd get a reward - a nice blue ribbon with their name on it - if they continued to draw. The second group wasn't told about the rewards but was given a blue ribbon after drawing. (This was the "unexpected reward" condition.) Finally, the third group was the "no award" condition. They weren't even told about the blue ribbons.

After two weeks of reinforcement, the scientists observed the preschoolers during a typical period of free play. Here's where the results get interesting: The kids in the "no award' and "unexpected award" conditions kept on drawing with the same enthusiasm as before. Their behavior was unchanged. In contrast, the preschoolers in the "award" group now showed much less interest in the activity. Instead of drawing, they played with blocks, or took a nap, or went outside. The reason was that their intrinsic motivation to draw had been contaminated by blue ribbons; the extrinsic reward had diminished the pleasure of playing with crayons and paper. (Daniel Pink, in his excellent book Drive, refers to this as the "Sawyer Effect".)

So the next time you're faced with a difficult task, don't look at a Nike ad, and don't think about the extrinsic rewards of success. Instead, ask yourself a simple question: Will I do this? I think I will.

Update: Daniel Pink has more.

cortex

Mon, 07/12/2010 - 04:53

Categories

Education

July 9, 2010

Cages and Cancer

There's an absolutely fascinating new paper by scientists at Ohio State University in the latest Cell. In short, the paper demonstrates that mice living in an enriched environments - those spaces filled with toys, running wheels and social interactions - are less likely to get tumors, and better able to fight off the tumors if they appear.

The experiment itself was simple. A large group of mice were injected with melanoma cells. After six weeks, the mice living in enriched environments had ...

Cages and Cancer

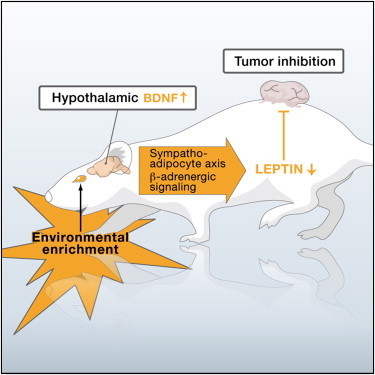

There’s an absolutely fascinating new paper by scientists at Ohio State University in the latest Cell. In short, the paper demonstrates that mice living in an enriched environments – those spaces filled with toys, running wheels and social interactions – are less likely to get tumors, and better able to fight off the tumors if they appear.

The experiment itself was simple. A large group of mice were injected with melanoma cells. After six weeks, the mice living in enriched environments had tumors that were approximately 75 percent smaller than mice raised in standard lab cages. Furthermore, while every mouse in the standard cages developed cancerous growths, 17 percent of the mice in the enriched enclosures showed no sign of cancer at all.

What explains this seemingly miraculous result? Why does having a few toys in a cage help prevent the proliferation of malignant cells? While the story is bound to get more complicated – there nothing is simple about cancer, or brain-body interactions – the researchers present a strikingly straightforward chemical pathway underlying the effect:

In short, the enriched environments led to increases in BDNF in the hypothalamus. (BDNF is a trophic factor, a class of proteins that support the survival and growth of neurons. What water and sun do for plants, trophic factors do for brain cells.) This, in turn, led to significantly reduced levels of the hormone leptin throughout the body. (Leptin is involved in the regulation of appetite and metabolism, and seemed to be down-regulated by slightly elevated levels of stress hormone.) Although a few earlier studies have linked leptin to accelerated tumor growth, it remains unclear how this happens, or if this link is really causal.

It’s important to not overhype the results of this study. Nobody knows if this data has any relevance for humans. Nevertheless, it’s a startling demonstration of the brain-body loop. While it’s no longer too surprising to learn that chronic stress increases cardiovascular disease, or that actors who win academy awards live much longer than those who don’t, there is something spooky about this new link between nice cages and reduced tumor growth. Cancer, after all, is just stupid cells run amok. It is life at its most mechanical, nothing but a genetic mistake. And yet, the presence of toys in a cage can dramatically alter the course of the disease, making it harder for cancerous cells to take root and slowing their growth once they do. A slight chemical tweak in the cortex has ripple effects throughout the flesh.

It strikes me that we need a new metaphor for the interactions of the brain and body. They aren’t simply connected via some pipes and tubes. They are emulsified together, so hopelessly intertwined that everything that happens in one affects the other. Holism is the rule.