Barry Hudock's Blog, page 27

August 12, 2013

Pope Francis’s Option for the Poor, Part 5: Continuity and Newness

So, our Pope Francis has clearly chosen to put poverty and the Church’s teaching about a preferential option for the poor at the center of his papal ministry. But how much of this is new, and how much is a restatement of formal Catholic teaching?

So, our Pope Francis has clearly chosen to put poverty and the Church’s teaching about a preferential option for the poor at the center of his papal ministry. But how much of this is new, and how much is a restatement of formal Catholic teaching?

Continuity

First, we should be clear that there is a lot in Francis’s approach to poverty and the poor that is not new. Of course, care for people who are poor has been a constant throughout Christian tradition. Notably, that includes approaching poverty not just through works of charity but through works of justice, that is, by attending to the social structures that support it.

To be sure, charity has been the dominant aspect throughout that history, but we find there too the Church’s insistence that in many ways, the help we offer to people in poverty is owed to them by right rather than simply offered out of kindness. It’s in the preaching of the great third- and fourth-century “fathers of the Church” and the thirteenth-century theology of St. Thomas Aquinas. It took a more prominent place in the nineteenth-century teaching of Leo XIII and has been embraced and developed by many of his successors. This includes, in modern times, frequently questioning the morality of liberal capitalism.

Pope Leo (pope from 1878-1903) authoritatively rejected the idea that labor is a commodity to be purchased for whatever the market will allow, that a wage contract is fair as long as the laborer is willing to agree to its terms. At a time when many in the West treated the laws of economics like the laws of nature, Leo said that’s not how it is. He also insisted that the state has a necessary place in the protection of workers and the poor.

Pope Pius XI (1922-1939), who introduced the term “social justice” into the Catholic vocabulary, was a radical critic of the capitalist system. In his encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, he called it an “unjust economic regime whose ruinous influence has been felt through many generations” and called for structures designed to limit competition in the marketplace that leads to exploitation of the poor. The theologian Donal Dorr has argued effectively that Pius XI rejected capitalism “not just in its present form, but in its essential nature.”

Pope Pius XII (1939-1958), though less radical in his criticisms of capitalism, called for a more just distribution of wealth and insisted on the universal destination of goods (relativizing the right to private property) in ways that would have made even most liberals in America today uncomfortable.

Pope John XXIII (1958-1963), also no radical on social or economic issues, did insist that “economic prosperity of any people is measured less by the total amount of goods and riches they own than by the extent to which these are distributed according to the norms of justice.” That passage comes from Pope John’s encyclical Mater et Magistra (n. 74), which offered a strong advocacy of increased social welfare programs designed to protect and assist the poor — so strong, in fact, that it led conservative leader William Buckley (founder of the National Review) to respond with his now famous “Mater si, Magistra no.” John also wrote strongly on the social nature of private property, arguing that property owners not only should give up some of what they own for the sake of a more just distribution of goods, but that they could be compelled by law to do so.

The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) proclaimed that “excessive economic and social differences between the members of the one human family or population groups cause scandal, and militate against social justice, equity, the dignity of the human person, as well as social and international peace” (in the constitution Gaudium et Spes n. 29). It called for “many reforms” of social and economic structures, including, for example, the creation of institutions to regulate international trade in order to protect the poor and the common good against exploitation that can result from following the “law of supply and demand” and the expropriation of massive Latin American estates owned by wealthy private individuals and families in the name of the social nature of private property.

Pope Paul VI (1963-1978) expanded the Church’s understanding of social justice to the international level. Particularly in his encyclical Populorum Progressio, he criticized the economic and social imbalances between rich and poor nations, including those left by past colonialism, caused by a present neo-colonialism, and reinforced by trade imbalances. He criticized dominant international trade relations as unjust and called for “bold transformations in which the present order of things will be entirely renewed or rebuilt” (PP 32). In echoes of Pope Pius XI’s radical criticism of capitalism, Paul wrote that

certain concepts have somehow arisen out of these new conditions and insinuated themselves into the fabric of human society. These concepts present profit as the chief spur to economic progress, free competition as the guiding norm of economics, and private ownership of the means of production as an absolute right, having no limits nor concomitant social obligations. This unbridled liberalism paves the way for a particular type of tyranny, rightly condemned by Our predecessor Pius XI, for it results in the “international imperialism of money.” Such improper manipulations of economic forces can never be condemned enough; let it be said once again that economics is supposed to be in the service of man.

In a landmark encyclical on evangelization, Pope Paul insisted that evangelization must include proclamation that the Gospel means “liberation from everything that oppresses man,” and while he notes that this means “above all liberation from sin and the Evil One,” it would also clearly include economic and social forces of oppression, for the Church seeks the conversion of “both the personal and collective consciences of people, the activities in which they engage, and the lives and concrete milieu which are theirs” (18). This includes liberation from “famine, chronic disease, illiteracy, poverty, injustices in international relations and especially in commercial exchanges, situations of economic and cultural neo-colonialism sometimes as cruel as the old political colonialism… This is not foreign to evangelization” (30).

Pope John Paul II (1978-2005) too called for a “transformation of the structures of economic life” (Redemptor Hominis, 16). Among his very many pastoral visits around the world, he expressed the Church’s option for the poor concretely by several significant personal visits to areas marked by poverty. Dorr points to one of these, his pastoral visit to Brazil in 1980, as especially important. In addition to expressing solidarity with the poor, Dorr suggests it also expressed solidarity with the bishops of that nation “in their commitment to putting the Church on the side of the poor and oppressed.” On that trip, he called upon government and economic leaders to “do all you can to ensure the disappearance, at least gradually, of that yawning gap which divides the few ‘excessively rich’ from the great masses of the poor, the people who live in grinding poverty.” And to the poor, he insisted that “God’s will” must never be an excuse to accept difficult conditions passively.

In his encyclical on work, Laborem Exercens, John Paul developed further the Church’s critique of capitalism, pointing out the structural injustices it encourages. And in another encyclical, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, he called upon Christians to live a more vibrant solidarity with the poor and criticized both the “structures of sin” that help to keep them poor and also the “super-development” of the West

which consists in an excessive availability of every kind of material goods for the benefit of certain social groups, easily makes people slaves of “possession” and of immediate gratification, with no other horizon than the multiplication or continual replacement of the things already owned with others still better. This is the so-called civilization of “consumption” or ” consumerism ,” which involves so much “throwing-away” and “waste.”

Pope Benedict XVI (2005-2013) offered a strong theological foundation for the Church’s approach to social justice, particularly in two major encyclicals Deus Caritas Est and Caritas in Vertitate. In the latter, he called for a greater openness to the element of “gratuitousness” in economic activity and commercial relationships, and he invited business people to consider “a profoundly new way of understanding business enterprise,” dual-purpose businesses that stand “between profit-based companies and non-profit organizations” by seeking to make a profit while also more intentionally serving the common good.

Clearly, the Church’s social justice tradition is long, rich, and startlingly challenging to modern capitalist economic structures.

What Is New in Francis?

One interesting thing that becomes clear by this review of the tradition of modern Catholic social teaching, specifically the ways it has expressed a preferential option for the poor and offered a critique of global capitalism, is that Pope Francis’s teaching and ministry is not particularly original or groundbreaking in its content. His concern for the poor and his insistence that poverty is an issue of justice as much as charity is consistent with those of his predecessors of modern times. His critique of capitalism is probably a bit more radical than some of his predecessors (Pius XII and John XXIII), but it is probably no moreso than the critiques offered by Popes Pius XI and Paul VI.

So it is fair to ask, is there anything new here? It seems that we ought to be able to say that there is, if only because, as Archbishop Chaput succinctly put it, ““The right wing of the church … generally have not been really happy about his election.” Indeed, the “conservatives” have clearly been troubled and flustered by Francis in a way that they seem not to have been by previous popes and their teaching.

Part of this is the directness with which he speaks and acts. Like Pope John Paul II, he has a knack for the dramatic gesture that catches people’s attention and conveys a powerful message before even a word is spoken. Powerful examples of this are the Pope’s journey to Lampedusa and his letter to the G-8 leaders, both mentioned in previous parts of this series.

Another part of it is his unwillingness to leave much “wiggle room” in his teaching and public comments, in which some conservatives have often found space to fit capitalist ideologies, though ultimately only by ignoring or even distorting many other elements of papal teaching.

But there is still more to it than all of this, and this final point is probably the most important. A review of previous, authoritative papal teaching, from which it is hard not to conclude that there is little that is new in what Francis is saying, makes the most important point somewhat obvious: Pope Francis’s preferential option for the poor and his presentation of Catholic social teaching has been, to many, far more effective, and he has posed more of a challenge to conservatives — and to each of us who live and breathe the modern capitalist, consumerist, superdeveloped culture — because of the integrity of his personal witness to the ideas he proclaims.

To be sure, previous popes were good teachers and good people. John XXIII and John Paul II will both — deservedly, in my opinion — soon be canonized. Perhaps Paul VI and Benedict XVI will be also someday. But Francis’s personal religious and ethical imagination has allowed him to put aside long-accepted expectations about how a pope should live and act in a way that has captured the attention of millions of people, and it has made his teaching all the more effective. And this remarkable and distinctive way of living and acting has itself become an important part of his option for the poor.

Pope Paul VI wrote memorably, nearly two generations ago now, that

for the Church, the first means of evangelization is the witness of an authentically Christian life, given over to God in a communion that nothing should destroy and at the same time given to one’s neighbor with limitless zeal. As we said recently to a group of lay people, “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.” St. Peter expressed this well when he held up the example of a reverent and chaste life that wins over even without a word those who refuse to obey the word. It is therefore primarily by her conduct and by her life that the Church will evangelize the world, in other words, by her living witness of fidelity to the Lord Jesus — the witness of poverty and detachment, of freedom in the face of the powers of this world, in short, the witness of sanctity. (Evangelii Nuntiandi, 41)

In his asking for the blessing of the people in St. Peter’s Square before offering them his own blessing on the day of his election, in his willingness to share a bus seat with his brother cardinals just after his election rather than travel in a separate transportation, in his choice of a rather simple Ford Focus rather than a custom-made BMW or Mercedes as the car he travels in, in his decision to forgo the papal residence in the apostolic palace in favor of a seemingly permanent guest room at Saint Martha House, in his Holy Thursday washing of the feet of troubled teens in a detention facility rather than clergy in St. Peter’s Basilica, and in a personal demeanor that radiates simplicity, humility, and joy, Pope Francis has shown how correct his predecessor Paul really was.

Francis’s lifestyle and ways of relating to those around him have made his witness much harder to ignore or distort or reject.

In Part 6, we’ll bring this series of posts to a conclusion. Previous parts can be found at these links: Part 1, 2, 3, 4. I want to acknowledge Donal Dorr’s Option for the Poor and for the Earth: Catholic Social Teaching as a helpful resource in my preparation of this post.

August 11, 2013

A little booktalk

At the annual meeting of the National Association of Pastoral Musicians a couple of weeks ago, the liturgical blog Pray Tell offered live webcasts of some of the most significant proceedings of the week and also some interesting panel discussions. (All of these are now archived here).

At the annual meeting of the National Association of Pastoral Musicians a couple of weeks ago, the liturgical blog Pray Tell offered live webcasts of some of the most significant proceedings of the week and also some interesting panel discussions. (All of these are now archived here).

For a little additional flavor, Rita Ferrone, one of the webcast moderators, did some brief “person on the street” interviews on the exhibition floor of the convention. She ended up with interesting exchanges about, for example, how paschal candles are made and how one composer creates liturgical music.

Among these conversations, Rita graciously asked if I might talk about one of my favorite books from among those Liturgical Press offered at our booth there. While almost everything else among the many Pray Tell Live webcasts and recordings that week was probably a lot more interesting, I’m always up for talking about books. My comments to Rita are now posted here at Pray Tell.

August 9, 2013

Barry on Busted Halo

I’m excited to say that I’ll be joining Fr. Dave Dwyer on his Busted Halo radio show in just a few days. That’s happening this coming Monday, August 12, at 8:20 pm Eastern Time. Fr. Dave and I will be talking about Catholic social teaching and my book, Faith Meets World.

I’m excited to say that I’ll be joining Fr. Dave Dwyer on his Busted Halo radio show in just a few days. That’s happening this coming Monday, August 12, at 8:20 pm Eastern Time. Fr. Dave and I will be talking about Catholic social teaching and my book, Faith Meets World.

Fr. Dave’s show airs (Monday through Friday, from 7 pm to 10 pm Eastern time) on Sirius XM Satellite Radio channel 129. The Busted Halo website is here.

August 8, 2013

Pope Francis’s Option for the Poor, Part 4: The Pope on “Savage Capitalism”

One admirable quality of Archbishop Charles Chaput is that he has no time for euphemism, coyness, or evasion. (For examples unrelated to the point I make below, see this interview and also comments of his reported here.) This quality was clear in comments that the archbishop made recently to journalist John Allen, Jr., on the topic of Pope Francis.

“[T]he right wing of the church,” Chaput said, “generally have not been really happy about his election.”

Chaput’s intention was not to criticize those who make up the Church’s “right wing.” Indeed, many would count him among them. (Chaput himself apparently would not. He says he knows of the right wing’s displeasure “from what I’ve been able to read and to understand,” as though he’s been studying the phenomenon in a textbook or a lab, and he refers to the people who make it up as “them,” not ”us.”) Chaput’s benign intentions are most clear in his insistence, in the same breath, that the Pope will “have to care for them [that is, the right wing], too.” He was simply making an observation about a reality that most other church leaders today understand — perhaps because they too are among the group in question — but have not yet acknowledged publicly.

Chaput is right, of course. “Conservatives” have been often frustrated, sometimes angered, and sometimes baffled by our new pope. The reasons are several. One of the strongest is the unambiguous and clear criticisms that Pope Francis has offered of the global economic system that many on “the right” have worked hard to defend not only as good but as consistent with Catholic doctrine.

To be sure, distrust of global capitalism has been a hallmark of modern Catholic social teaching from its inception. But it is fair to say that previous popes have presented that teaching in a way that has often allowed space for a vibrant defense of free-market capitalism in the context of church teaching. (Anyone familiar with the work of Michael Novak, George Weigel, and Robert Sirico will immediately think of them here.) With Francis, that space is much smaller, and his thinking allows for a defense that is not so much vibrant as tepid.

Indeed, Pope Francis has not hesitated to warn us of a “savage capitalism” that is dominant today and to speak of the consumerism upon which it depends as “one of the most dangerous threats of our times.” These convictions are a fascinating aspect of the option for the poor that has become central to his ministry and draws him closer to what liberation theologians intended originally by the term in a way that previous popes had perhaps avoided.

A Threat to Faith

Francis’s comment about “one of the most dangerous threats of our times” was especially eye-catching, since it came less than a week after his election as pope. When a brand new pope uses a phrase like that, it’s worth taking notice, because it will offer some important insight into where his priorities will be. Coming from the mouth of Benedict, for example, the subject of the statement would likely have been secularism, or maybe relativism. From many other church leaders here in the U.S. today, it would be religious freedom or gay marriage.

What threat earns such strong words from Francis? It is, he said, “the vision of the human person with a single dimension to prevail, according to which man is reduced to what he produces and to what he consumes.” The word we use to describe that vision is consumerism, which is not only a hallmark of our Western capitalist economies, but an aspect of it that is essential to its success.

More recently, the Pope spoke of this consumerism as a threat to the personal encounter with Jesus that each Christian is called to. Having just returned from the remarkable experience of World Youth Day 2013 in Rio de Janiero, the Pope commented in a Sunday afternoon Angeles address in Saint Peter’s Square: “The encounter with the living Jesus, in the great family that is the church, fills the heart with joy, because it fills it with true life, a profound goodness that does not pass away or decay. But this experience must face the daily vanity, the poison of emptiness that insinuates itself into our society based on profit and having (things), that deludes young people with consumerism.”

So, the well-being of capitalism depends on a vibrant consumerism, and a vibrant consumerism is a threat to one’s relationship with Jesus. The conclusion is pretty clear: a strong capitalistic economy is a threat to the relationship with Jesus of each person who lives within it — and therefore, of course, to their faith and salvation. No wonder Francis calls it a “poison.” And his reasons for speaking of “savage capitalism” become more clear. The latter comment came during a May 2013 visit to a soup kitchen and women’s shelter run at the Vatican by the Missionaries of Charity. “A savage capitalism,” he said, ”has taught the logic of profit at any cost, of giving in order to get, of exploitation without thinking of people… and we see the results in the crisis we are experiencing.”

Truth to Power

Though at the food kitchen the Pope was speaking among people living in poverty, he has not hesitated to speak the same truths directly to the powerful leaders who guide the political and, in important ways, economic structures of our society.

This came first in the context of a May 2013 meeting of the Pope with a group of new ambassadors to the Holy See, a rather routine event on his calendar that would ordinarily call for some perfunctory and unremarkable comments by the Pope. But on this occasion, Pope Francis chose to address the world economic situation in words that were anything but perfunctory. As I have pointed out already on this blog, depending on your choice of news source, you would have read the next day that the Pope slammed, attacked, denounced, ripped, hit out at, blasted, railed against, warned against, criticized, or condemned the “the cult of money” that marks the global economy, an economy that he called “faceless and lacking any truly humane goal.”

It is difficult to pick out just a few lines from what he had to say. His comments that day were packed with phrases and sentences quite jarring in their meaning:

Ladies and Gentlemen, our human family is presently experiencing something of a turning point in its own history, if we consider the advances made in various areas. We can only praise the positive achievements which contribute to the authentic welfare of mankind, in fields such as those of health, education and communications. At the same time, we must also acknowledge that the majority of the men and women of our time continue to live daily in situations of insecurity, with dire consequences. Certain pathologies are increasing, with their psychological consequences; fear and desperation grip the hearts of many people, even in the so-called rich countries; the joy of life is diminishing; indecency and violence are on the rise; poverty is becoming more and more evident. People have to struggle to live and, frequently, to live in an undignified way. One cause of this situation, in my opinion, is in the our relationship with money, and our acceptance of its power over ourselves and our society. Consequently the financial crisis which we are experiencing makes us forget that its ultimate origin is to be found in a profound human crisis. In the denial of the primacy of human beings! We have created new idols. The worship of the golden calf of old (cf. Ex 32:15-34) has found a new and heartless image in the cult of money and the dictatorship of an economy which is faceless and lacking any truly humane goal.

The worldwide financial and economic crisis seems to highlight their distortions and above all the gravely deficient human perspective, which reduces man to one of his needs alone, namely, consumption. Worse yet, human beings themselves are nowadays considered as consumer goods which can be used and thrown away. We have begun a throw away culture. This tendency is seen on the level of individuals and whole societies; and it is being promoted! In circumstances like these, solidarity, which is the treasure of the poor, is often considered counterproductive, opposed to the logic of finance and the economy. While the income of a minority is increasing exponentially, that of the majority is crumbling. This imbalance results from ideologies which uphold the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation, and thus deny the right of control to States, which are themselves charged with providing for the common good. A new, invisible and at times virtual, tyranny is established, one which unilaterally and irremediably imposes its own laws and rules. Moreover, indebtedness and credit distance countries from their real economy and citizens from their real buying power. Added to this, as if it were needed, is widespread corruption and selfish fiscal evasion which have taken on worldwide dimensions. The will to power and of possession has become limitless.

Concealed behind this attitude is a rejection of ethics, a rejection of God. Ethics, like solidarity, is a nuisance! It is regarded as counterproductive: as something too human, because it relativizes money and power; as a threat, because it rejects manipulation and subjection of people: because ethics leads to God, who is situated outside the categories of the market. These financiers, economists and politicians consider God to be unmanageable, unmanageable even dangerous, because he calls man to his full realization and to independence from any kind of slavery. Ethics – naturally, not the ethics of ideology – makes it possible, in my view, to create a balanced social order that is more humane. In this sense, I encourage the financial experts and the political leaders of your countries to consider the words of Saint John Chrysostom: “Not to share one’s goods with the poor is to rob them and to deprive them of life. It is not our goods that we possess, but theirs” (Homily on Lazarus, 1:6 – PG 48, 992D).

We can’t miss the fact that Francis insists here that our economic structures and practices deny “the primacy of human beings”; that they are like ”the golden calf of old”; and that they are based upon “the gravely deficient human perspective, which reduces man to one of his needs alone, namely, consumption.” He has the chutzpah not only to cite the powerful statement of St. John Chrysostom that summarizes so well the Church’s teaching on the universal destination of goods — “Not to share one’s goods with the poor is to rob them and to deprive them of life. It is not our goods that we possess, but theirs” — but even directly to invite “the financial experts and the political leaders of your countries” to consider them.

If you’re tempted to dismiss these comments of his as having been made at an insignificant gathering to which few will pay attention, then don’t miss the letter the Pope wrote to British Prime Minister David Cameron on the occasion of the June 2013 G8 Summit, which gathered together the leaders of the eight most powerful nations in the world. Here the Bishop of Rome writes directly to those who hold the seats of highest political power on the planet. In it, he insisted repeatedly that economic activity must be guided by ethics, always serving the needs of the human person, and not the other way around. In a key paragraph he wrote:

Moreover, the goal of economics and politics is to serve humanity, beginning with the poorest and most vulnerable wherever they may be, even in their mothers’ wombs. Every economic and political theory or action must set about providing each inhabitant of the planet with the minimum wherewithal to live in dignity and freedom, with the possibility of supporting a family, educating children, praising God and developing one’s own human potential. This is the main thing; in the absence of such a vision, all economic activity is meaningless.

Acknowledging a place in economic activity for freedom and creativity – important aspects of what we call the free market – the Pope said that “all political and economic activity, whether national or international” must be carried out in a way that promotes and guarantees respect for human solidarity, “with particular attention to the poorest.” He praised the group’s efforts “to eliminate definitively the scourge of hunger and to ensure food security.”

To be sure, elements of this thinking have been present in papal teaching before — notably in that of Pius XI, Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI. But all of the above, coming rapidly and in the very first months of a new pontificate, represents a much more direct papal assault than we have previously seen upon the economic structures of the West, the aggressive capitalism they support, and the relentless consumerism upon which it all depends.

Part 5 of this series will consider how Pope Francis’s option for the poor is in continuity with his predecessors and how it is new.

August 4, 2013

Pope Francis’s Option for the Poor, Part 3: Leading a pastoral revolution

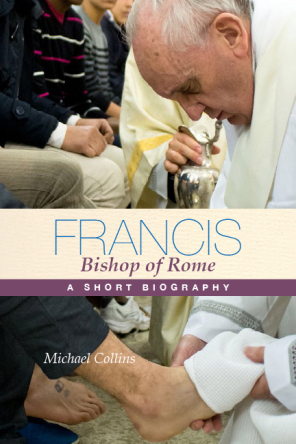

Following the March 2013 papal election of Jorge Maria Begoglio, Liturgical Press — the Catholic publishing house for which I work — published a biography of the new pope. As anyone who was paying attention at the time was aware, several other publishers did, too. Wishing to set this biography off from its competition and at the same time to express something about our new pope’s distinctive style, I gave careful thought to the image we chose for the cover of the book and finally settled on a photograph of Francis washing the feet of the young inmates of the juvenile detention facility in Rome, where he celebrated his first Holy Thursday Mass as Pope. (See the image to the right.)

Following the March 2013 papal election of Jorge Maria Begoglio, Liturgical Press — the Catholic publishing house for which I work — published a biography of the new pope. As anyone who was paying attention at the time was aware, several other publishers did, too. Wishing to set this biography off from its competition and at the same time to express something about our new pope’s distinctive style, I gave careful thought to the image we chose for the cover of the book and finally settled on a photograph of Francis washing the feet of the young inmates of the juvenile detention facility in Rome, where he celebrated his first Holy Thursday Mass as Pope. (See the image to the right.)

As we prepared the book for publication, the cover designer working on the project came to me with an interesting question. A small tattoo — one of poor quality and probably homemade — was clearly visible on one of the bare feet that were prominent in the photo. Perhaps she ought to Photoshop the tattoo out of the photo, she suggested, to clean it up a bit?

It took only a few moments for us to make a decision on that question. Francis’s Holy Thursday Mass at a youth detention facility was unprecedented. Long Vatican custom called for the Pope to celebrate the Mass of the Lord Supper in the splendor of St. Peter’s Basilica and to wash the feet of twelve priests. And here was the new pope, dramatically shirking not only the customary setting and the customary choice of whose feet would be washed, but also the liturgical rubric that called for the washing of men’s feet. Here was Pope Francis at a youth detention facility (joovie, as American kids call it), washing the feet of its inmates, including a couple of women, one of whom was Muslim. I bet no pope has ever washed a tattooed foot before on Holy Thursday. That tattoo spoke volumes about what was happening with that Mass — and also about the man who had made the choice to do it. The tattoo had to stay.

Bergoglio in the slums

The special concern for the poor and marginalized that has recently earned Pope Francis the moniker “apostle of the slums” has surprised almost no one who knew him before his election. It was a major element of his life and ministry as Archbishop of Buenos Aires as well, such that one priest who knew him well could say to journalist John Allen, Jr., that it was in the city’s slums that Bergoglio breathed the “oxygen” that nourished his ministry and his understanding of the church.

Bergoglio, Allen has reported, oversaw a “pastoral revolution” in those slums that included hand-picking several dedicated priests (“Bergoglio’s ‘infantry’ in the villas”) to live and work there, guiding programs like a drug addiction recovery center, a trade school, a home for the elderly, a community newspaper, and more. Under his leadership, parishes in those desperate regions blossomed into vibrant centers of faith and social services.

Significantly, Bergoglio did not preside over all of this from afar, nodding his approval from the safety and comfort of his office. He visited frequently, Allen writes, “walking the streets, talking to the people, leading them in worship and standing with them when times were tough.” Allen’s report quotes a Buenos Aires priest:

“When he would visit here, he’d take the bus and then he’d just come walking around the corner like a normal guy,” Isasmendi said.

“For us, it was the most natural thing in the world. He’d sit around and drink mate (an Argentinian tea), talking with people about whatever was going on. He’d start talking to the doorman or somebody about a book he was reading, and I could leave him there and go do something else, because Bergoglio was totally comfortable.”

The Pope and the Poor

Since his election as Bishop of Rome, we have seen these same pastoral convictions expressed in many dramatic and remarkable ways. Consider briefly:

Immediately following that election, Pope Francis asked his fellow Argentines not to travel to Rome for his inauguration, but rather to give the money they would have spent on the trip to the poor.

On Holy Thursday 2013 — as we noted above — he celebrated the Mass of the Lord’s Supper at Rome’s Casa Del Marmo Youth Detention Centre, washing the feet of twelve of its young inmates, including women, one of whom was Muslim.

In April 2013, the Pope decisively “unblocked” the beatification process of slain Archbishop Oscar Romero. As Archbishop of San Salvador in El Salvador, Romero was assassinated in 1980 for challenging his government’s brutal oppression of the poor. He probably represents better than any other twentieth century figure the remarkable blossoming of the Church’s awareness of its call to an option for the poor that came about precisely in Latin America following the Second Vatican Council.

In a July 2013 address to seminarians, he asked them to avoid buying new and luxury cars, saying, “It hurts me when I see a priest or a nun with the latest model car…. If you like the fancy one, just think about how many children are dying of hunger in the world.”

Along the same lines, the Pope has made a fascinating choice of his vehicle of choice for traveling around Vatican City and elsehwhere. Rather than the custom-made Renault, BMW X5, or Mercedes that had previously served as typical papal modes of transportation, Francis has taken to riding in the back seat of a Ford Focus, a compact car with a modest sticker price.

During his July 2013 pastoral visit to Rio de Janiero, Brazil, on the occasion of World Youth Day, Francis insisted on the addition to his schedule of a visit to one of the city’s most deperate and violent slums. On that occasion, he walked the streets, visited a family’s home, and said in his public comments, “The measure of the greatness of a society is found in the way it treats those most in need, those who have nothing apart from their poverty…. I would like to make an appeal to those in possession of greater resources, to public authorities and to all people of good will who are working for social justice: never tire of working for a more just world, marked by greater solidarity.”

More dramatic and potentially more consequential than any of these moments was Pope Francis’s very first pastoral visit outside of Rome, to the tiny Sicilian island of Lampedusa. It serves as an arrival point for immigrants making their way, often packed into rickety wooden boats exposed to the elements, from Africa to Italy by sea. Tens of thousands have made such a voyage in recent years. For a good perspective on the significance of the location, journalist John Allen, Jr., provides a helpful comparison:

To get a sense of its impact, imagine a newly elected president of the United States announcing that his first trip outside D.C. would be to the border to see for himself where people have died and to embrace detainees in an ICE facility. It would be taken as a bold way of proclaiming that compassion will be a hallmark of the new administration. That’s exactly how Italians, and Europeans generally, are reacting to Francis’ planned outing.

While at Lampedusa, the Pope threw a wreath of flowers into the sea to remember the tens of thousands of migrants who have lost their lives while crossing the Mediterranean. He celebrated Mass with the people of the island and met with immigrants. Perhaps most fascinating, the Pope chose to wear purple vestments, the liturgical color of Lent, for this Mass on a weekday of ordinary time. He used the prayers from the Mass for the Forgiveness of Sins, and in his homily, he called the Mass ”a liturgy of repentance.” Catholic News Service’s Cindy Wooden provided more striking details:

The Mass was filled with reminders that Lampedusa is now synonymous with dangerous attempts to reach Europe: the altar was built over a small boat; the pastoral staff the pope used was carved from wood recycled from a shipwrecked boat; the lectern was made from old wood as well and had a ship’s wheel mounted on the front; and even the chalice — although lined with silver — was carved from the wood of a wrecked boat.

And rather than being transported while on the island in the popemobile, he travelled in a borrowed 20-year-old Fiat Campagnola.

The Pope’s homily at the Mass in Lampedusa included comments such as these:

So many of us, even including myself, are disoriented, we are no longer attentive to the world in which we live, we don’t care, we don’t protect that which God has created for all, and we are unable to care for one another. And when this disorientation assumes worldwide dimensions, we arrive at tragedies like the one we have seen.

“Where is your brother?” the voice of his blood cries even to me, God says. This is not a question addressed to others: it is a question addressed to me, to you, to each one of us. These our brothers and sisters seek to leave difficult situations in order to find a little serenity and peace, they seek a better place for themselves and for their families – but they found death. How many times to those who seek this not find understanding, do not find welcome, do not find solidarity! And their voices rise up even to God!

***

In Spanish literature there is a play by Lope de Vega that tells how the inhabitants of the city of Fuente Ovejuna killed the Governor because he was a tyrant, and did it in such a way that no one knew who had carried out the execution. And when the judge of the king asked “Who killed the Governor?” they all responded, “Fuente Ovejuna, sir.” All and no one! Even today this question comes with force: Who is responsible for the blood of these brothers and sisters? No one! We all respond this way: not me, it has nothing to do with me, there are others, certainly not me. But God asks each one of us: “Where is the blood of your brother that cries out to me?” Today no one in the world feels responsible for this; we have lost the sense of fraternal responsibility; we have fallen into the hypocritical attitude of the priest and of the servant of the altar that Jesus speaks about in the parable of the Good Samaritan: We look upon the brother half dead by the roadside, perhaps we think “poor guy,” and we continue on our way, it’s none of our business; and we feel fine with this. We feel at peace with this, we feel fine! The culture of well-being, that makes us think of ourselves, that makes us insensitive to the cries of others, that makes us live in soap bubbles, that are beautiful but are nothing, are illusions of futility, of the transient, that brings indifference to others, that brings even the globalization of indifference.

Again and again in a pontificate that is still less than 5 months old, Pope Francis has made clear that top priorities of his ministry will include presence to and pastoral care of the poor, drawing the attention of the church and the world to the situations of people living in poverty, and challenging the indifference of the rich that helps that poverty to remain and to grow. He has not been satisfied with a few perfunctory comments or even strong statements made from the safety of the apostolic palace (a place of residence he has eschewed). Both prior to and after his election, he has gone to the places where poor people are, and he has gone far beyond what was expected of him.

In Part 4 of this series, we’ll consider one further important and fascinating aspect of his option for the poor (and the part that most annoys and challenges many who might otherwise be most readily disposed to support him): the Pope’s challenge to the dominant global economic system.

Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here.

July 27, 2013

3,000,000

At this very moment, 3 million people are gathered with Pope Francis in Rio de Janeiro. For some perspective on that, see Wikipedia’s list of the largest peaceful gatherings of human beings in one place in all of history, here.

The distinctiveness of Francis

Interesting comments on the distinctiveness of Pope Francis:

[For those alienated from the church,] John Paul was difficult to understand because he was a philosopher. Benedict just didn’t connect with them, and he had a lot of bad press, they would call him the Rottweiler, he didn’t capture a lot of people’s imagination. But this guy does.

Must be some authority-shirking, liturgy-trashing, social justice dissident speaking there, just trying to mold Francis in their own image, at the expense of previous popes whom they hated anyway, right?

Nope, that’d be Fr. Mitch Pacwa, EWTN star and nobody’s liberal.

As an admirer of both John Paul II and Benedict XVI, I have been sympathetic to the complaints of some “conservatives” about the potshots that some have taken at these two remarkable men in order to explain the distinctiveness of Francis (you would think by some accounts that these two were Borgia popes or that Francis was the first pope to kiss a baby). So I’m intrigued at Pacwa’s willingness to, well, take a few potshots.

Don’t get me wrong — I have no doubt the man loves JP2 and B16. (I do, too.) My point is, Francis is different, distinctive, and more effective as a pastor and a Christian witness in some important ways. And to say so, perhaps by comparisons, need not be considered, in itself, disrespectful.

By the way, I enjoyed Pacwa’s metaphor quoted in the same article: “All the popes are against consumerism, but this guy brings the hay down to where the goats can get it.”

July 26, 2013

Romero’s cause proceeding “with great speed”

Interesting new comments here, published today, from Archbishop Gerhard Müller, prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, on the cause for the beatification of Archbishop Oscar Romero. It is important to note, for context, that in beatification/canonization causes, the CDF often reviews the writings and public comments of candidates to ensure they are free of doctrinal error. (This is my translation from the article, which is in Spanish.)

The process toward the doctrinal “nihil obstat” [that is, approval] in the Congregation [for the Doctrine of the Faith] has proceeded normally and under Benedict XVI even saw a decisive acceleration. We cannot forget that in 2007, during his trip to Brazil, Pope Ratzinger said clearly that he considered Romero worthy of beatification. Now, with Pope Francis, the process is proceeding with great speed in the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

July 25, 2013

Quote of the day

– Pope Francis to 5.000 young Argentineans at Rio de Janiero Cathedral, 7/25/13 (source)

Pope Francis does NOT love the world, dammit! And other things First Things wants you to get straight

The First Things “On the Square” blog offered a post the other day from author William Doino, Jr., called “Five Myths About Pope Francis.” Doino sees some dastardly thinking in the air about our Pope, and he wishes to debunk it all. (Thanks to Michael Sean Winters for drawing my attention it, but I can’t help but expand upon his brief comments.)

“Myth” #1 that Doino seeks to dismiss is that “Francis is the anti-Benedict.” The first thing to say is that there is absolutely no one who is suggesting that Francis is “the anti-Benedict,” as though the two are as different as night and day or somehow dramatically at odds in terms of doctrine or theology. What Doino offers here is a straw man. Everyone who has paid any attention knows that Francis seems to like Benedict, respect Benedict, and that he embraces and seeks to proclaim the same Catholic doctrine embraced and proclaimed by Benedict.

But it should be obvious to all that this is not an all-or-nothing matter. We do not have to choose between Francis being either the anti-Benedict or a Benedict replica. And the fact is, in some significant and interesting ways, Francis is different than Benedict. This is okay and to be expected. Benedict was different than John Paul II in some significant and interesting ways, too. What bugs the First Things folks is that some of the differences (his application of the Church’s social teachings, for example, and maybe his liturgical style) suggest that ideas they would want us to think are unacceptable are in fact quite legitimate among Catholics.

“Myth” #2 that Doino opposes is that “Francis is Not a Cultural Warrior.” Doino rejects the idea that the Pope “avoids confrontation and strident denunciations, and wants no part of any culture war,” apparently because to do so would be bad for a Pope. Doino is clearly bothered by Sandro Magister’s observation that “after 120 days of pontificate Pope Francis has not yet spoken the words abortion, euthanasia, homosexual marriage,” for he says it’s hard to imagine a more misleading statement.

Magister’s comment is certainly not insignificant, but there is probably absolutely no one who would take from it that it means Francis is in any way in favor of these practices or lacks the will to oppose them. What is does say a lot about, in my opinion, is Francis’s pastoral priorities.

Francis is indeed, in some ways, a culture warrior. The problem for the First Things crowd is the aspects of the culture with which he has chosen, so far, to do battle. And yet raise his voice he does, prophetically, and he does it by drawing upon on the same Catholic moral tradition from which Benedict and John Paul II drew. He has done this from the very first days of his pontificate, when he pointed out clearly what he sees to be “one of the most dangerous threats of our times” — but failed to mention the threats that Doino and others at First Things would prefer did. “Above all,” he said, ”we must keep alive in our world the thirst for the absolute, and must not allow the vision of the human person with a single dimension to prevail, according to which man is reduced to what he produces and to what he consumes: this is one [of the] most dangerous threats of our times.”

Pope Francis played the role of ”culture warrior” quite dramatically more recently at Lampedusa, when he donned purple vestments for Mass on a weekday of Ordinary Time, used the prayers from the Mass for the Forgiveness of Sins, and called for our repentance for the way we have treated immigrants. The pope preached boldly:

“Where is your brother?” the voice of his blood cries even to me, God says. This is not a question addressed to others: it is a question addressed to me, to you, to each one of us. These our brothers and sisters seek to leave difficult situations in order to find a little serenity and peace, they seek a better place for themselves and for their families – but they found death. How many times to those who seek this not find understanding, do not find welcome, do not find solidarity! And their voices rise up even to God!…

The culture of well-being, that makes us think of ourselves, that makes us insensitive to the cries of others, that makes us live in soap bubbles, that are beautiful but are nothing, are illusions of futility, of the transient, that brings indifference to others, that brings even the globalization of indifference.

Francis also stood as culture warrior in his May address to new diplomats to the Vatican in which he criticized the world’s economic system. He said,

The worship of the golden calf of old (cf. Ex 32:15-34) has found a new and heartless image in the cult of money and the dictatorship of an economy which is faceless and lacking any truly humane goal. The worldwide financial and economic crisis seems to highlight their distortions and above all the gravely deficient human perspective, which reduces man to one of his needs alone, namely, consumption…. I encourage the financial experts and the political leaders of your countries to consider the words of Saint John Chrysostom: “Not to share one’s goods with the poor is to rob them and to deprive them of life. It is not our goods that we possess, but theirs.

And by the way, the world press had no doubts on that occasion about whether Francis might be considered a culture warrior. As I pointed out at the time, depending on where you got your news, you could read that Pope Francis slammed, attacked, denounced, ripped, hit out at, blasted, railed against, warned against, criticized, or condemned the “cult of money” that pervades much of the world economy.

“Myth” #3 that Doino wishes to dispell is “Francis is a ‘Social Justice’ Pope.” Because, you know, heaven forbid we think that!!

As evidence that Francis is not a “social justice pope,” Doino points out that he is “not exclusively concerned about poverty” and because he ”believes that individual conversion must precede societal improvement.” Of course, if to be a “social justice pope” means that he can be concerned only and exclusively about poverty and that he thinks individual conversion has no place in societal improvement, there never has been and never will be such a creature. But if a “social justice pope” is a pope who makes social justice a pastoral priority, then he is clearly that. So, in very real ways, was John XXIII. And Paul VI. And John Paul II. And Benedict XVI.

Francis has added some new twists to his pastoral ministry in pursuit of social justice, and it’s these that make the neo-conservatives at First Things uncomfortable (as Archbishop Chaput has pointed out bluntly this week).

Doino’s “Myth” #4 is that “Francis Will Be More Charitable Toward Dissenters.” This is an odd one to include here, because to my mind, the only thing anyone can say one way or another right now about how Francis will relate to prominent theologians who dissent in significant ways from Church teaching is that it remains to be seen. What we can say is that there is more than one way for Church authorities to address doctrinal dissent. We can also say that it is not altogether clear that what has been treated as dissent over the past several decades has, in every case, been that. Francis has a different personality and, as I said, different pastoral priorities. Might he take a different approach? Yes, he might. We don’t know.

Finally, Doino’s “Myth” #5 is “Francis Loves the World.” Horrors! How did this despicable accusation get out, and how can we stop it?!? Have no fear, Doino is quick to step in decisively: “This is the greatest misconception of all.”

After all, we can’t have anyone thinking that Francis has the same love for the world that, like, God does.

Granted, Doino allows that Francis loves people (whew!) and also loves creation. But apparently we can’t say that he loves the world.

In conclusion, get it right: Francis is the same as Benedict, is a neo-conservative culture warrior, is no social justice pope, is going to nail dissenters, and hates the world. Or something like that.