Barry Hudock's Blog, page 20

December 26, 2013

“The solution is solidarity”: Mary Elizabeth Hobgood’s Dismantling Privilege

Working through an engaging, interesting, and challenging book is a great way to wrap up a year. At the close of 2013, Mary Elizabeth Hobgood’s Dismantling Privilege: An Ethics of Accountability has been a pleasure. Though there is plenty in the book that I will not mention here, three of its major themes are race, economics, and sexuality, and Hobgood left me thinking about all three more deeply.

Working through an engaging, interesting, and challenging book is a great way to wrap up a year. At the close of 2013, Mary Elizabeth Hobgood’s Dismantling Privilege: An Ethics of Accountability has been a pleasure. Though there is plenty in the book that I will not mention here, three of its major themes are race, economics, and sexuality, and Hobgood left me thinking about all three more deeply.

For Hobsgood, whiteness is about far more than skin color. On a cultural level, it’s the denial of relationality and connectednesss to one another and to community. Hobgood says we who are white have agreed to deny ourselves of these — though they are so important to what it means to be human – as the price of having the competition, efficiency, and technological advancement of the capitalist society that we have built for ourselves. We have built and bought into this kind of society, and all of the unearned privileges that come with whiteness are, unconsciously, the rewards for our willingness to make the self-denials. The unearned privileges of being white are the “emotional compensation for the suffering involved in being faithful to industrial morality” (49). Our fear and distrust of non-whites are rooted in our resentfulness that they have managed to hold onto those things better than we have.

The damage that we have inflicted on non-white people through the social structures that support our whiteness is, of course, obvious, both in our history and in our present. But Hobgood insists, insightfully, that we have also hurt ourselves, too, through the emotional and moral damage that have come with all this self-denial. By forsaking relationships with the earth and the people around us, we have denied ourselves access to our more relational selves. “The system of white racial identity is constructed to diminish the relational capacity of whites” (61).

Hobgood also offers a compelling and challenging look at economic structures. With our terminology about and systems constructed around markets and money, we ignore the relational and historical aspects of our economy. We keep ourselves ignorant of our connections to the people who make our clothes and provide our food. We find ways to talk about poverty in terms of the failures or weaknesses or bad luck of people who are poor, ignoring history and social structures that, as contributing factors, loom high above such minor considerations. She points out quite effectively that we rationalize the shipping of jobs overseas for the drastically lower costs involved, and congratulate ourselves at how appreciative these workers are for the jobs and the wages that are so much higher than they would be without us there, “never mind the centuries of colonial and neocolonial impoverishment by the West, which robbed them of control over their land, labor, and resources” (94).

All of this is profoundly non-Christian and anti-Christian. “Though largely ignored by First World Christians, biblical tradition is clear that poverty is not a mark of having sinned [or of personal failures], but a result of being sinned against” (68). She’s right that “beyond diffuse sentiment and generalized moral challenge … none of the official churches assists people in analyzing the roots of poverty and other forms of economic injustice” (70). As with whiteness, the damage done extends to the privileged elites whom the system supports, as well as to the poor who are hurt by it. ”Everyone’s sense of virtue is degraded” (84). Capitalism robs us of our capacity to trust others, and “trust is essential for human flourishing and the development of empathy, cognition, and creativity” (100).

Less compelling and harder for me to agree with was Hobgood’s chapter on sexuality, which is so radical as to seem disconnected with reality. “Human beings,” she writes, ”are socially constructed, not necessarily biologically constructed, as male or female” (108). There’s far more here than a call for greater respect and acceptance of gay people or acknowledgement by the churches of gay marriage. Hobgood argues, “‘Properly gendered’ (heterogendered) makes and females, heterosexuality, monogamy, or even biological maleness and femaleness is not a natural or universal human condition” (122). Following through on these principles, she advocates “freedom in gender and sexual expression” and “gender fluidity and fluidity in sexual practice” (124).

While I realize that these currents of thought exist out there, it’s hard to see how they are compatible with the Christian moral tradition and foundational Catholic teaching. It’s one thing to criticize the patriarchal structures of the church or advocate opening the sacrament of marriage to gay couples; it’s a whole other thing to discard the value or normativity of monogamous marriage. I had a sense that Hobsgood’s positions here might sound fascinating in the context of academia, but would wreck havoc in real life. (Indeed, we’ve been inching closer to “gender fluidity and fluidity in sexual practice” for decades and are worse off for it.)

Also pushing Hobgood from the realms of credibility are seemingly wild-eyed assertions such as: ”Catholic women have learned that without their intact hymens or multiple experiences of married motherhood, they have no right to exist” (132); and “This belief [that sexual desire is beyond the control of men] is supported by traditional moral theology that defined birth control as more sinful than rape because with rape procreation, the only legitimate purpose of sexual desire, was at least possible” (132-133). (I have a fairly thorough familiarity with “traditional moral theology” and have yet to stumble across even an obscure suggestion of this latter kind, much less its strong presence in anything close to formally endorsed doctrine or theology.)

In all of the above aspects of life, Hobsgood says, the solution is solidarity, and on this point she is surely right. By our rejection of solidarity and relationality, we have damaged people, society, and our very selves in myriad ways. Dismantling Privilege has challenged me in new ways to stand against this powerful cultural current and become more truly the person — and the person in community — that God created me to be.

[I should note that the copy I read is the first edition of the book, published in 2000. I see the publisher, Pilgrim Press, released a revised and updated edition in 2009, and I'm not sure what differences it may include.]

December 23, 2013

Krista Tippett on being against the commercialization of Christmas

Despite what Fox News would have us believe, the real War on Christmas is, of course, its commercialization. The idea that we have to mark the sacred feast by flying headlong into a national spending rampage is a surer sign of our secularization than any generic holiday greeting from the Walmart cashier will ever come close to being. So protesting that commercialization by refusing to participate in the annual buying rites is surely something that many serious Christians have considered already.

Still, this new reflection by Krista Tippett (one of my favorite voices on radio) on Christmas and why she’s not giving gifts this year articulates things afresh and is worth a look. My two favorite passages:

I don’t like — don’t approve, refuse to throw myself into — the spirit of obligatory gift-giving. In my lifetime, this has become existentially linked to a commercial orgy that has now even co-opted the ritual angle. We have Good Friday and Maundy Thursday; we have Black Friday and Cyber Monday. Unlike Good Friday and Maundy Thursday, however (though like “fiscal cliff”) these terms are repeated and reported by the most serious of journalists. Like all mantras of ritual, they work on us from the inside. They are an economic event by which we measure a certain kind of cultural health.

This form of cultural health is not health at all. It is overwhelmingly an exercise in excess and trivia.

***

Here’s what I take seriously. There is something audacious and mysterious and reality-affirming in the assertion that has stayed alive for two thousand years that God took on eyes and ears and hands and feet, hunger and tears and laughter and the flu, joy and pain and gratitude and our terrible, redemptive human need for each other. It’s not provable, but it’s profoundly humanizing and concretely and spiritually exacting. And it’s no less rational — no more crazy — than economic and political myths to which we routinely deliver over our fates in this culture, to our individual and collective detriment.

Of course, not giving gifts, either to avoid complicity or to protect one’s own spiritual well-being, makes good sense. But it also would take a good bit of courage, even audacity, because it risks misunderstanding, misinterpretation, or incomprehension by family members and loved ones. It’s not surprising that Tippet, as she acknowledges, did not take this step until after her own kids were grown. And though completely understandable, waiting until then inevitably means first joining the annual spending rites with much gusto at the time when not doing so could perhaps make the most difference, before finally turning one’s back on them. It’s a capitalistic version of Saint Augustine’s classic prayer, “Lord, make me chaste, but not yet.”

We of the Christian community need to find a way to think this through together, with greater attentiveness, cooperation, and intention. It could represent an important grass-roots ecumenical effort with real consequences both inside and outside the church.

December 22, 2013

Saint Marianne’s remains on the move

One great thing about living in Syracuse, NY, during the four happy years our family lived there was the “presence” of Mother Marianne Cope (or at least her remains). Mother Marianne was a “blessed” during our years there; she has since been canonized a saint, by Pope Benedict in October 2012.

One great thing about living in Syracuse, NY, during the four happy years our family lived there was the “presence” of Mother Marianne Cope (or at least her remains). Mother Marianne was a “blessed” during our years there; she has since been canonized a saint, by Pope Benedict in October 2012.

Saint Marianne was born in Germany and raised in Utica, NY, before taking up a religious vocation with the Franciscan Sisters of Syracuse. She was administrator of a hospital that still thrives in Syracuse and also the mother superior of the congregation when, in 1883, she moved with six other sisters to Hawaii, to take up humble and heroic work of Saint Damien De Veuster in the last years of the latter saint’s life, ministering to victims of Hansen’s disease (leprosy) for 35 years. She had planned to go just temporarily, to help the other sisters establish their work there, but became so engaged in the humble and heroic ministry that she never left, dying there in 1918.

At her canonization, Pope Benedict commented in his homily:

At a time when little could be done for those suffering from this terrible disease, Marianne Cope showed the highest love, courage and enthusiasm. She is a shining and energetic example of the best of the tradition of Catholic nursing sisters and of the spirit of her beloved Saint Francis.

Her body remained in Hawaii until 2004, when it was moved back to Syracuse just prior to her beatification. It has been kept in a modest shrine beneath the altar of the main chapel of the Sisters of St. Francis motherhouse. Now she’s going back to Hawaii.

The Associated Press reports:

The relocation is necessary because the buildings of the campus where her remains are housed no longer are structurally sound, requiring the sisters to move to another part of Syracuse, the order said. A piece of her remains, known as a relic, will stay behind in Syracuse.

The sisters decided “through great deliberation and prayer” to return the remains to Hawaii, Sister Roberta Smith said.

“Hawaii is a major destination for the people the world over, and having St. Marianne’s remains there would ensure a steady stream of pilgrims who could continue to be inspired by her, seek her intercession and imitate her dedication and faith,” Smith said.

Bishop Larry Silva of the Honolulu diocese called Marianne’s return a “wonderful blessing.” The sisters approached him a couple of months ago about the possibility of returning her remains, Silva said, and he learned of the final decision Wednesday.

I suppose it all makes sense, but as a former Syracusian who visited the tomb with my family, the move is disappointing.

December 19, 2013

Happy birthday, PEPFAR.

We ought not to let 2013 pass without marking the 10-year anniversary of one of the most remarkable accomplishments of George W. Bush’s presidential administration. Indeed, it may be one of the most successful U.S. diplomatic initiatives of our generation and certainly the one most admirable for its impressive combination of scientific-medical research, government action, and humanitarian aid. (H/t NPR.)

We ought not to let 2013 pass without marking the 10-year anniversary of one of the most remarkable accomplishments of George W. Bush’s presidential administration. Indeed, it may be one of the most successful U.S. diplomatic initiatives of our generation and certainly the one most admirable for its impressive combination of scientific-medical research, government action, and humanitarian aid. (H/t NPR.)

It’s unfortunate, given all of that, that so few Americans are very familiar with The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR. In more formal legislative terms, we’re talking about the United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act of 2003 (and renewed five years later as the Tom Lantos and Henry J. Hyde United States Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008). The legislation provided tens of billions of dollars ($15 billion in 2003 and $48 billion in 2008) of U.S. foreign aid to fight the spread of AIDS in Africa, with a success that has been dramatic and undeniable.

Here’s Harold Varmus — the 1989 Nobel Prize-winner in physiology and medicine — summarizing that success well (in a narrative of the law’s origins that is well worth a look):

[B]y preventing and treating HIV infection on a large scale in the developing world, PEPFAR has turned around declining life expectancies in many countries and likely saved some countries—even an entire continent—from economic ruin….

By 2012, it was estimated that PEPFAR had supplied more than five million patients with antiretroviral drugs, up from 1.7 million in 2008; that nearly a million infants had been protected from HIV transmitted from their mothers; and that nearly fifty million people had been tested for infection. Recognizing these accomplishments and many more, the most recent report from the IOM concluded that “PEPFAR has played a transformative role…(in)…the global response to HIV….” and cited “the pride, gratitude and appreciation expressed by partner country governments, implementing partners, providers” and others. Calling PEPFAR “a lifeline” that has restored hope, the report ended by saying that “PEPFAR has achieved—and in some cases surpassed—its initial ambitious aims.”

One of the most dramatic aspects of PEPFAR’s success is the effect on life expectancy in African countries. After the arrival of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and prior to the initiation of PEPFAR in the early 2000s, life expectancies had been falling precipitously in African countries with a high prevalence of HIV infection. But the number of deaths in such countries fell steeply after the start of PEPFAR. Effects like these explain why PEPFAR has such high visibility in many African countries and has inspired so much gratitude toward the United States.

We truly do have President Bush to thank for this in some very real ways. Bush was, as Varmus explains, “deeply involved strategically at every stage—conception, development, launch, and implementation—of this large, complex, and hugely successful project.” He did it against the anti-foreign-aid instincts of his own party, against the objections of some legislators whom he could most often count as allies, and to the general indifference of some who would have been far more enthusiastic about the idea had it not been Bush proposing it.

The work continues. Just last month, the U.S. Congress demonstrated continuing commitment to the legislation through the passage of the PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act of 2013. PEPFAR is surely one of the brightest parts of the legacy of George W. Bush, not to mention an accomplishment in which every U.S. taxpayer also has played a part.

December 18, 2013

Learning to live, learning to die: West on Dorothy Day

If you’ve got about 45 minutes to treat yourself, I recommend some time with Dr. Cornel West. America magazine’s In All Things blog has posted the full video of an address he delivered in November at Catholic Worker’s Maryhouse in New York City.

The title of his talk is “Dorothy Day: Exemplar of Truth and Courage,” but I’m not sure the title does justice to the inspired, contemporary, and freewheeling nature of the talk. As should be anything that lives up to who Dorothy was, West’s address is both a delight and a challenge.

More helpful background on the talk and on West himself, as well as the video, is here.

December 12, 2013

Dying young in West Virginia

Some of the finest people I have known live in southern West Virginia. Almost three years after leaving there, my wife and I not only remember fondly the neighbors and friends we knew in those mountain communities; we also continue to try to live up to values that we learned from them through those relationships and daily interactions. So it’s heartbreaking to read a headline like this one, published on Monday:

McDowell Men Have Shortest Life Expectancy, Women Second Shortest in U.S.

That’s McDowell County it’s referring to, at the southern tip of the state, which is just down the road a few miles from where we lived before our 2011 move to central Minnesota. Though such stats on McDowell are nothing new now, there was a time, more than a half century ago, when McDowell was thriving, a national leader in coal production. That means the folks there provided, through dangerous and back-breaking work, the power that fueled the rapid post-WWII economic and technological development of which all of us in the U.S. are still beneficiaries.

Nowadays… well, the WV Public Broadcasting article at the link above provides some context to the headline:

McDowell County has suffered major job loss and mass exodus of people after many coal mines closed. In 1950 there were close to 100,000 people. The population has plunged to about 21,000 in 2012.

The median household income in McDowell County between 2007-2011 was about $22,000; far less than the national median of about $53,000 and even West Virginia’s median, $40,000.

Circumstances in neighboring Mingo County, where I lived, are nearly as bad. (In the important report cited in the article, McDowell County ranks 55th out of 55 counties in the state; Mingo is at 53. Number 54, Wyoming County, is also a neighbor. They are the poorest counties in a very poor state.)

The reasons for the sad stats are many, and they are frustratingly intertwined. But among the lessons is a stark illustration of the reality of structures of injustice and the far-reaching impacts they can have. Indeed, some of those structures and their impacts have a lot to do with why my wife and I and our kids are not still there, despite our great enjoyment of the place and its people. (We left largely in the interests of our kids’ educations.)

We were not natives to area, but as the population statistics above suggest, many who were have also moved elsewhere. Indeed, there were occasions during my days there that I thought it might make the most sense for the entire population to just pick up and leave the region behind, lock, stock, and barrel. I’m not sure anyone could live there long without considering that option at least fleetingly at times, in the moments of greatest frustration. But then the richness of the place — the strength and big-heartedness of the people and the beauty and power of the land — comes back to startle you again, day in and day out, and you can’t believe that such an idea had ever crossed your mind.

For problems so long-standing and intractable, solutions are obviously hard to come by. But if you’re looking for a way to make a difference, Christian Help of Mingo County does an admirable job of helping people survive the poverty that holds such a power over the region, while ABLE Families offers effective support to people who seek, one by one and family by family, to work their way out of that poverty or avoid it altogether. The Appalachian Catholic Worker is still another local program well worth support. I know each program well. Each is grassroots, working on shoestrings at a direct and one-to-one level. God bless them and the people they serve.

December 10, 2013

“Economics is a branch of moral philosophy”: Deneen in The American Conservative

Maybe the great take-away that we get from the publication of Evangelii Gaudium is that while we made much of John Paul II being a great communicator and Benedict XVI an erudite theologian, most people (Catholics and non-Catholics, admirers and opponents of both) managed quite well never to pay much attention to what they said, at least on certain topics. “We have reached a new level of political absurdity when the right is mad at the pope and the left wants to anoint his head with oil,” wrote a Washington Post columnist this week, seemingly unaware that the only absurdity is that neither camp, despite JP2 and B16 saying the same things in more authoritative documents, gave much thought to offering the same sort of responses to those guys for the past three decades.

And so well worth our time is a very fine piece just posted by The American Conservative. “We now see the Pope being criticized and even denounced from nearly every rightward-leaning media pulpit in the land,” writes Patrick J. Deneen. He considers the reasons for this — and the reasons that JP2 and B16 did not receive similar approbrium. A snippet:

In the past several months, when discussing Pope Francis, the left press has at every opportunity advanced a “narrative of rupture,” claiming that Francis essentially is repudiating nearly everything that Popes JPII and Benedict XVI stood for. The left press and commentariat has celebrated Francis as the anti-Benedict following his impromptu airplane interview (“who am I to judge?”) and lengthy interview with the Jesuit magazine America. However, in these more recent reactions to Francis by the right press and commentariat, we witness extensive agreement by many Catholics regarding the “narrative of rupture,” wishing for the good old days of John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

But there has been no rupture—neither the one wished for by the left nor feared by the right. Pope Francis has been entirely consistent with those previous two Popes who are today alternatively hated or loved, for Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI spoke with equal force and power against the depredations of capitalism. (JPII in the encyclical Centesimus Annus and Benedict XVI in the encyclical Caritas in Veritate.) But these encyclicals—more authoritative than an Apostolic Exhortation—did not provoke the same reaction as Francis’s critiques of capitalism. This is because the dominant narrative about John Paul II and Benedict XVI had them pegged them as, well, Republicans. For the left, they were old conservatives who obsessed with sexual matters; for the right, solid traditionalists who cared about Catholicism’s core moral teachings. Both largely ignored their social and economic teachings, so focused were they on their emphasis on “faith and morals.” All overlooked that, for Catholics, economics is a branch of moral philosophy.

There is more to Deneen’s article than simply pointing out that Francis’s teaching on economic morality amounts to a restatement of what the Church has long held, so don’t let me citing a piece keep you from clicking over to read the whole thing. It’s important and well-written stuff.

December 9, 2013

The Joy of the Gospel — thoughts on chapter two

Chapter two of Evangelii Gaudium is about the context within which the Church carries out its evangelizing mission. This is a difficult topic, because the context will be different depending on location on the globe, so almost by definition, the accuracy of the Pope’s analysis will vary depending on where you’re reading it. But he has surely put his finger on several sore wounds that fester in American society. The accuracy of his diagnosis is revealed most tellingly in the great discomfort with which many American Catholics have received it. Actually, almost everyone in the Church is sure to find something in chapter two to make them uncomfortable.

If there’s an overall theme of the chapter, a core at the center of the many dangers it brings to our attention, it’s individualism and self-centeredness. Francis is right to emphasize it, because it’s unquestionably an -ism for which both sides of the “culture wars,” both inside and outside the Church, bear much guilt for embracing. It made me think this would be a helpful focus of even more attention going forward. In all kinds of ways, individualism (as the Pope says) “favors a lifestyle which weakens the development and stability of personal relationships and distorts family bonds.” In that short description, we can find reference to consumerism, unfettered capitalism, abortion, contraception, and much more.

***

The Pope’s comments about our “economy of exclusion and inequality” are striking. He notes bluntly that it “kills.” Just so we’re clear on the kind of economy he’s talking about, he calls out the “trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world.” These theories, a hallmark of the “Reagan revolution,” have been defended ferociously by many Americans, including some American Catholics, for decades. Of them the Pope says: “This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting.”

Many commentators have objected to papal teaching like this in the past — no, it’s not new at all; what’s new is the plain-spoken clarity with which he presents it — by saying that the Pope is not an economist and not qualified to teach with authority about economic matters. It’s the conservatives who are doing this today, vociferously and repeatedly, as they encounter this document. That’s no different than objecting to the Church’s teaching on abortion or contraception by pointing out that the Pope is not a doctor and not qualified to teach with authority about biological matters. In both cases, the objection misses the point, or perhaps better, intentionally obscures it. There are profound moral implications to the economic choices we make – just as there are to some bodily/medical choices that we make – and about these, the Pope is indeed (as Catholics understand it) qualified to speak.

***

I read the Pope’s observations about pastoral workers with some ambivalence. At times, I wasn’t sure he was talking about the priests, parish ministers, and religious sisters and brothers I have known for decades. For example, when he talked about the “inordinate concern” of some pastoral workers “including consecrated men and women,” “for their personal freedom and relaxation” and “priests who are obsessed with protecting their free time,” I thought this surely describes some, of course, but not most. Most of the priests and sisters I know work very hard at the ministries they perform, often giving little thought to their “personal time” and how they would like to spend it.

On the other hand, there are probably many who serve the Church today who would benefit from some careful reflection upon the Pope’s (perhaps too verbose) words of criticism of

the self-absorbed promethean neopelagianism of those who ultimately trust only in their own powers and feel superior to others because they observe certain rules or remain intransigently faithful to a particular Catholic style from the past. A supposed soundness of doctrine or discipline leads instead to a narcissistic and authoritarian elitism, whereby instead of evangelizing, one analyzes and classifies others, and instead of opening the door to grace, one exhausts his or her energies in inspecting and verifying. In neither case is one really concerned about Jesus Christ or others…. In some people we see an ostentatious preoccupation for the liturgy, for doctrine and for the Church’s prestige, but without any concern that the Gospel have a real impact on God’s faithful people and the concrete needs of the present time. In this way, the life of the Church turns into a museum piece or something which is the property of a select few. (n. 94-95)

I noticed the other day that one conservative blogger is actually making fun of the Pope for his word choice here (“self-absorbed promethean neopelagianism”), a sure sign that the Pope has hit close to home. It takes wisdom, prudence, and maturity to be able to see the difference between attentiveness to “soundness of doctrine or discipline” and exercise of “a narcissistic and authoritarian elitism” wrapped up in “inspecting and verifying.” Some — like the blogger I just mentioned — have failed in that.

***

The Pope also raises the topic of women in the Church. Again here, I admit to being ambivalent. I was a young man when Pope John Paul II published his 1994 apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, On Reserving Priestly Ordination to Men Alone. It seemed (and seems) like a pretty definitive conclusion to the question of women priests. At the conclusion of that very brief document (just over 1000 words), the Pope wrote, in very formal and solemn verbiage: “Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church’s divine constitution itself, in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32) I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church’s faithful.”

Pope Francis has now reaffirmed this teaching several times since his election, as he does in n. 104 of Evangelii Gaudium, much to the disappointment of many within the Church who otherwise are thrilled with his teaching and ministry. “Conservatives” have pointed out on several occasions that Pope Francis, though he is saying things in ways we’re unaccustomed to hearing them from a pope, has not changed any church teaching and, they are quick to add, he can’t.

The thing that gnaws at me these days when questions like women’s ordination and gay marriage come up is this: there are doctrines that had been considered closed questions before that subsequently were changed (though the preferred word is “developed”). Yes, I know there is a significant difference theologically between a teaching “changing” or being “developed” by the magisterium. But the thing is, I’m talking about instances in which the development that happened would have been considered, before its endorsement by the Church, as a change, even a reversal. The one that’s foremost in my mind at the moment, mostly because of the work I’ve been doing recently on John Courtney Murray, is the Church’s teaching on religious freedom. Call Vatican II’s teaching on religious freedom a development if you want, but the Church’s highest doctrinal authorities who opposed Murray in the two decades prior to the Council flatly rejected his theology because they understood it as opposed to Church doctrine. One could say in somewhat cynical terms that it went from being a subversion of Church teaching to a development in Church teaching when the Church finally accepted it.

Many conservatives who are uncomfortable with what the Pope says in Evangelii Gaudium have been quick, over the past couple of weeks, to point out that an apostolic exhortation is not an encyclical, which is more authoritative. It is not an infallible pronouncement. (The conclusion that they leave mostly implicit — because it’s unseemly for “conservatives” to say it, perhasp — is that it’s therefore not so bad to doubt the truth of its contents.) For example, here’s Father Robert Sirico (president of the neo-conservative Acton Institute), assuring his listeners: “One of the first things you need to know about an apostolic exhortation is that in Catholic theology it does not accupy the highest place of magisterial teaching, but is nonetheless worthy of our consideration and real rich and deep and honest discussion.” And another traditionalist blogger was quick to point out, “It is not an encyclical. It is not an apostolic letter. It is only an apostolic exhortation.” But why is this any different than someone else pointing out that Ordinatio Sacredotalis is “only” an apostolic letter?

Another thing that is different about my own perspective now than it was twenty years ago is that I have daughters now — five of them. It’s one thing to think in theoretical terms that there is something men can do that women can’t, that there’s a sacrament of the Church that men can receive that women can’t (but no corresponding sacrament available to women but not men); it’s another thing to say it to your young daughters, and to have to try to explain it when the statement catches their attention and they ask deeper questions about it. (And yes, I know the arguments that support the teaching quite well — those who heard me offer them with conviction at the time Ordinatio Sacerdotalis was released will attest to it.)

Am I saying I think women should be priests? No, I’m saying my Church, whose authority to interpret and teach God’s revelation I accept, teaches pretty clearly that they should not. That teaching has been repeated pretty emphatically and very recently by some remarkably holy and wise popes. But I’m also aware of several very compelling reasons that otherwise good Catholics might think otherwise, and also of some pretty clear examples of instances when doctrine has changed/developed. So I can’t know for certain that no change is ahead. Some will say that’s a wimpy way to approach it. Maybe they’re right. Maybe if the change could happen, I need to decide if I think it should happen, and if I do, should say so. But I guess I’m not ready to take that step; it’s where I am these days.

***

More on Evangelii Gaudium soon.

December 6, 2013

The single most stunningly inaccurate observation about Evangelii Gaudium

I’ve been moving along through Evangelii Gaudium — savoring it, really — and will likely post a few more thoughts on it soon. Of course, the parts on economics are striking and the parts on evangelization are exhilarating. That the Pope sees the two topics as so crucially intertwined is both fascinating and terribly challenging to all of us who make up the Church, especially in the west, and the plain and often delightful language in which Francis presents all this makes that fact very hard to miss.

And so that’s why I find this, from Jeff Mirus at CatholicCulture.org, to be perhaps the single most stunningly inaccurate observation yet offered about the document (which he offers as the opening sentence of his commentary on EG):

There is only so much one can say about Pope Francis’ new apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), before we come up against the fact that this is a post-synodal text from which only a relatively few people are going to benefit.

I admit I was initially flummoxed as to how Mr. Mirus could possibly be reading the same words I am in that document and yet write the ones above. The primary reason he offers for his conviction that the document will be so useless is that there is so much in it, on so many different topics (“covering everything from how to prepare a good homily to the implementation of Catholic social teaching,” Mirus observes). He calls EG “long and inevitably disjointed,” and it makes me wonder if he ever used these words to describe any of Pope John II’s famously long and loaded teaching documents, about which a good friend of mine (and JP2 enthusiast) once observed, “He thinks he always has to start at the beginning of salvation history and work through it with reference to whatever topic he is covering.”

In truth, of course, just about everything in Francis’s new document can pretty easily be categorized under two broad topics: evangelization and economic morality (which is born out by Mirus’s “good homily and Catholic social teaching” line), and I think the Pope makes it quite plain that they are both included because his intention is to consider our evangelizing mission within the economic-social context in which we must go about it. Indeed, that’s what makes Francis’s document so remarkably relevant to all of us.

One is tempted to think, then, that there’s more to Mr. Mirus’s desire to put the document aside than the fact that there’s too much in it. This becomes a little clearer with this line:

If you want to gain the main thrust of Pope Francis’ call to evangelization without laboriously reading an over-long and inevitably disjointed document, I recommend reading Chapter One (“The Church’s Missionary Transformation”) and Chapter Five (“Spirit-Filled Evangelizers”). These are the first and last chapters, in which the Pope is saying pretty much what he wants to say.

Funny how chapters one and five are the two that say the least about the injustices of our market economy. Hm. Perhaps those are things that Mirus pretty much wishes Francis had not said.

Take my advice and read the whole thing. You’ll find, as many have, that Francis has absolutely no difficulty saying pretty much what he wants to say. The problem is, what he has to say often is pretty much of a challenge to those who read it.

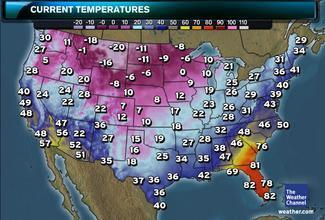

Lots of minus signs in front of those numbers

It’s cold in quite a few places in the U.S., and here in central Minnesota, it’s COOOOLLLLD. Just rolled out of bed to begin my morning routine and checked the current temp before heading out to walk the dog. Our friends at the Weather Channel are telling me that right now, actual temp in our town is -8°, but windchill factor puts us at -22°.

It’s cold in quite a few places in the U.S., and here in central Minnesota, it’s COOOOLLLLD. Just rolled out of bed to begin my morning routine and checked the current temp before heading out to walk the dog. Our friends at the Weather Channel are telling me that right now, actual temp in our town is -8°, but windchill factor puts us at -22°.

Of course, that’s going to shoot up as the day goes on, so by 1:00 pm, we’ll be at 1° actual / -15° windchill. After that, it’s back downhill, with forecasted overnight numbers -12° actual / -28° windchill.

Now where’s that leash? Time for that walk.