Barry Hudock's Blog, page 14

August 15, 2014

“We may not be murderers, but we are inheritors.”

“To Be White and Reckon with the Death of Michael Brown,” a new piece by columnist Courtney E. Martin at the On Being website, is a fine one. It all leads up to a powerful closing paragraph:

The only way to honor Michael Brown and his family, to honor all Americans who reckon with the scourges of racism every single day, is to own that we may not be murderers, but we are inheritors. We must talk to our ugliest ghosts. We must work on strategies to dismantle structural racism. We must express our outrage at what is happening out there — in Ferguson, in Staten Island, in Oakland. But, we must also investigate what is happening in here, inside every one of us — our own unexamined privilege, our own patronizing cure-alls, our own fears. We are not bad. We are not good. We are part of the tragic story and the opportunity for transformation.

August 13, 2014

Was Bonhoeffer gay?

Two tweets from Fr. Jim Martin today:

Was Dietrich Bonhoeffer gay? According to this superb biography, which I just finished, very probably: http://religionandpolitics.org/2014/07/30/the-life-of-dietrich-bonhoeffer-an-interview-with-charles-marsh/

And does it matter if Bonhoeffer was gay? Yes, it does. Because it reminds us that gay men and women can be holy–very holy, even martyrs.

August 11, 2014

500 years ago this week: the conversion of Bartolomeo de las Casas

Here’s an anniversary worth noting. This week marks the 500th anniversary of the conversion of Fr. Bartolomeo de las Casas. Las Casas was the 16th century Spanish Dominican friar who came to “the New World,” participated in the atrocities committed by the Spanish against the native Americans, and later opposed these atrocities vehemently.

Las Casas came to the Americas as a lay man. He was 18 years old in 1502, when he arrived with his father, who was a merchant, in what is today Cuba. They were among the first European settlers in the Americas. He obtained a plantation and bought slaves. But he soon decided to become a priest, and in 1510, he became the first European to be ordained a priest in the Americas. In 1513, he served as chaplain to Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the Spanish conquistador, in his mission to take control of the island of Cuba from its natives. In this role, he witnessed even crueler treatment of native Americans than he had seen (and committed) previously.

It was in August 1514 — precisely 500 years ago — that the most significant conversion of Las Casas’s life occurred. He was studying a passage from the book of Sirach in preparation for a homily. It was Sirach 34: 18-22 (here is today’s New American Bible translation):

Tainted his gifts who offers in sacrifice ill-gotten goods!

Mock presents from the lawless win not God’s favor.

The Most High approves not the gifts of the godless,

nor for their many sacrifices does he forgive their sins.

Like the man who slays a son in his father’s presence

is he who offers sacrifice from the possessions of the poor.

The bread of charity is life itself for the needy;

he who withholds it is a man of blood.

He slays his neighbor who deprives him of his living;

he sheds blood who denies the laborer his wages.

The words dug into his conscience. He prepared a special sermon about the treatment of the Indians for the feast of the Assumption, August 15. He set free his slaves and began preaching frequently that the other colonists should do the same. Las Casas went on to become one of the foremost voices in defense of the human dignity of the native American peoples — which was mostly, unfortunately, ignored.

Five hundred years ago: the conversion of Fr. Bartolomeo de las Casas, who raised his voice with courage in opposition to what would become one of the most tragic offenses against human dignity in history.

July 28, 2014

“An exquisitely timed act of nature”

Let’s face it, in our information- and news-soaked culture, we learn a lot of startling things on a regular basis. It takes a lot to surprise us. But this morning’s broadcast of NPR’s Morning Edition had me muttering “holy shit” as I listened on the way to work.

Let’s face it, in our information- and news-soaked culture, we learn a lot of startling things on a regular basis. It takes a lot to surprise us. But this morning’s broadcast of NPR’s Morning Edition had me muttering “holy shit” as I listened on the way to work.

That came when I heard Elizabeth Shogren’s report on an “intrepid” (her adjective, and a good one) species of bird and its annual migration — get this — “from the southern tip of South America to the Arctic and back every year”! Yes, that’s 9,300 miles of flying.

But its long distance flight is not all that’s amazing about this creature. It is one actor is a complex and remarkable happening — what Shogren aptly describes as “an exquisitely timed act of nature.” Shogren reports:

Tens of thousands of red knots stop to refuel in the Delaware Bay just as the world’s largest concentration of horseshoe crabs arrives on the same beaches to lay eggs…. By the time the birds get to Delaware’s shore they’ve been flying for five days straight — and they’re starving….

The birds come here because this is where the strange, prehistoric-looking horseshoe crab comes to lay its eggs.

“There isn’t anything better for these birds to eat,” says Kalasz. “These little tiny horseshoe crab eggs are just packed full of fat,” he adds, holding a cluster of thousands of tiny greenish balls.

At high tide, thousands of these crabs, each the size of a salad bowl, cluster along the water’s edge. The gentle surf is foamy with the males’ sperm. As many as ten male crabs compete to fertilize each female’s eggs.

The superabundance of this nutritious food is essential for the red knots, which double their body weight in about 10 days of gorging, before heading north.

But herein lies a warning, yet another reminder of the myriad ways we are allowing climate change to upset our planet’s delicate ecological balance. Shogren:

The crabs and the birds have to arrive at the same time if the birds are going to make it to the Arctic to nest, and warming water temperatures could prompt the crabs to lay eggs before the birds arrive.

Meanwhile, rising seas and bigger storms are washing away the beaches, which make one of the biggest weight gains in animal kingdom possible, according to Kalasz.

“In a number of years, we could lose this very special place,” he says. “And if that were to occur, I’d feel a tremendous sense of loss.”

The changing climate is creating other risks for the red knot along its migration path, including in the Arctic where it nests.

A tremendous loss indeed.

The report, both text and audio, are here.

July 25, 2014

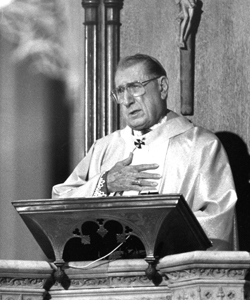

Dolan channels O’Connor

I was and remain a big fan of Cardinal John O’Connor, who was archbishop of New York from 1984 to his death in May 2000. There was a time when I put a lot of work into writing a biography of O’Connor, including conducting dozens of interviews with his family, friends, and co-workers throughout his lifetime. (Unfortunately, I put the project on hold when I had difficulty finding a publisher and have never gotten back to it.)

One of the beautiful and inspiring things about his personality and ministry was the striking indignation he felt at instances of disregard for human dignity. He was not afraid to express this indignation plainly and oftentimes poetically (for the man was a great writer and speaker).

One of my favorite examples of this was a time when he had announced that he would donate all of his social security income as a retired U.S. Navy admiral to a fund for the education of black youths. He apparently received some strongly objections to this from at least a few outspoken conservatives (whom, one might say, represented the “base” of those who most often supported a lot of what he did).

From the pulpit of St. Patrick’s Cathedral one Sunday morning, O’Connor read a bit from one letter he had received on it. The writer threatened to stop making his weekly contributions to St. Patrick’s and, in a sort of protest, throw black buttons into the collection basket instead. The Cardinal then commented, basically saying that he was sorry the writer felt that way, but that if his support for the education of young black people is what caused the black buttons to come in the collection basket, then he would wear those buttons on his cassock with pride.

Anyway, I thought of this yesterday when I came across (thanks to a link from Michael Sean Winters) a recent blog post by O’Connor’s successor, Cardinal Timothy Dolan. In it, Dolan commented on the negative reaction of some Americans to recent flood of tens of thousands of refugee children from Central and South America. He specifically cited an angry mob that turned back a busload of children in southern California, yelling “get out!” while shaking their fists.

Dolan writes:

It was un-American; it was un-biblical; it was inhumane. It worked, as the scared drivers turned the buses around and sought sanctuary elsewhere.

The incendiary scene reminded me of Nativist mobs in the 1840’s, Know-Nothing gangs in the 1850’s, and KKK thugs in the 1920’s, who hounded and harassed scared immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and Blacks.

I think of this sad incident today, the feast of New York’s own Kateri Tekakwitha, a native-American (a Mohawk) canonized a saint just three years ago. Unless we are Native Americans, like Saint Kateri, our ancestors all came here as homesick, hungry, hopeful immigrants. I don’t think there were any Mohawks among that mob attacking the buses of refugee women and children.

He then compared the mob to the crowd of folks in McAndrews, Texas, who recently welcomed a similar busload of refugees, in this case offering the kids “a meal, a cold drink, a shower and fresh clothes, toys for the kids, and a cot as they helped government officials try to process them and figure out the next step.”

I loved reading the post and admire Cardinal Dolan’s intention to remind us of what we’re supposed to be about, not just as Catholics, but as human beings. His strident indignance at the failure of some to recognize the human dignity of those around them is inspiring and calls out the best in us — in me, anyway. His words are a welcome reminder to me of the wise leadership of his great predecessor, Cardinal O’Connor.

Regarding these young refugees, by the way, Minnesota Public Radio offered a fine report yesterday, explaining “Who are the kids of the refugee crisis?”

July 19, 2014

On the road

My full time work at Liturgical Press has had me on the road more often than not over the last six weeks, which is one reason for the infrequent posts here lately. Since the beginning of June, I’ve found myself in San Diego, London, South Bend (my recent Veritas in Caritate anniversary reflections were posted from there), and St. Louis — and a 10-day family vacation in Pennsylvania also happened during that time!

It’s all been good and invigorating (and also tiring, as travel can be), but I’m glad to be back home in Minnesota now and ready to get back to the office on Monday morning.

The most recent trip was to the National Association of Pastoral Musicians convention in St. Louis. During those days, I did this interview with Nathan Chase — currently the moderator of the Pray Tell blog, which broadcast live from the convention floor — about several new and exciting books from Liturgical Press. Have a look.

July 2, 2014

Caritas in Veritate, Five Years On (Part 4: Unless They Are Also Witnesses)

[This is the fourth and final post in a series intended to mark the fifth anniversary of Pope Benedict's encyclical, Caritas in Veritate. See also: Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.)

Five years after the publication of Caritas in Veritate, what is there to say that was not said at the time? What do we see now, with a perspective of five years, that we might not have seen then?

Most importantly, we see it from a vantage point of the Pope Francis pontificate. In this sense, a look back at CiV should remind us that Benedict’s successor is not nearly the radical break with his predecessors as many would have us believe he is. Indeed, CiV caused the same sort of agita five years ago as Francis’s Evangelii Gaudium did upon its November 2013 release.

In fact, it may be fitting that we mark not only the fifth anniversary of CiV’s release, but also of one of the clearest examples of cafeteria Catholicism since the invention of the term. On the very day of the document’s release, National Review Online published an essay by commentator George Weigel, who could only explain the presence of so much in CiV that made him uncomfortable – advocacy of a more just redistribution of wealth and a world political authority, for example – by suggesting that Benedict found himself unable to say no to officials at the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace who wanted to include them.

“Benedict XVI, a truly gentle soul, may have thought it necessary to include in his encyclical these multiple off-notes, in order to maintain the peace within his curial household,” Weigel wrote. He suggested one might mark the “obviously Benedictine” passages with a gold marker and those that “Benedict evidently believed he had to try and accommodate” with a red one. (It is fascinating to note, given Benedict’s lionization among conservatives, that the encyclical that garnered this sort of reaction will likely stand as his most lasting contribution to the Church’s doctrinal heritage.)

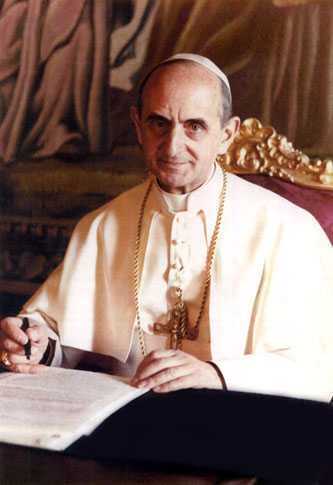

Still, we should recall that such anxiety five years ago was mostly limited to those most familiar with the intricacies of Catholic doctrine, while Francis’s similar teaching on economic morality has been blasted by the likes of radio commentator Rush Limbaugh radio show and Fox Business host Stuart Varney. This surely says something about the effectiveness of Francis’s communication style or, perhaps moreso, of his lifestyle in getting people to listen to and understand what he has to say. It is a bracing reminder of Pope Paul VI’s insistence two generations ago, in his landmark encyclical on evangelization, that people of our age listen more attentively to witnesses than to teachers, and if we do listen to teachers, it is because they are also witnesses (Evangelii Nuntiandi 41).

We find echoes of CiV throughout Evangelii Gaudium, perhaps most strongly in its second chapter, where the Pope calls us to offer a courageous “No to the new idolatry of money.” Francis’s assertion that the recent financial crisis “originated in a profound human crisis: the denial of the primacy of the human person!” and his call for a financial reform rooted in ethics and “a more humane social order” where “Money must serve, not rule!” sounds a lot like Benedict’s insistence that “[t]he economy needs ethics in order to function correctly – not any ethics whatsoever, but an ethics which is people-centered.”

The combined efforts of both these popes have now decisively moved modern Catholic teaching firmly beyond a conception of social ministry as founded solely upon justice, that is on moral duty and obligation (though neither leaves any question that it is). Both insist that this ministry ultimately is rooted in love and flows generously and gratuitously from our awareness of God’s love for us and for others.

Both have also called us to a greater capacity to be shocked by the conditions under which too many of our sisters and brothers live and die on a daily basis. Benedict laments in CiV that “[i]nsignificant matters are considered shocking, yet unprecedented injustices seem to be widely tolerated. While the poor of the world continue knocking on the doors of the rich, the world of affluence runs the risk of no longer hearing those knocks, on account of a conscience that can no longer distinguish what is human.” This sounds a lot like Francis’s warning of a “globalization of indifference” that results from a “culture of prosperity” that “deadens us.” He continues, “[W]e are thrilled if the market offers us something new to purchase. In the meantime all those lives stunted for lack of opportunity seem a mere spectacle; they fail to move us.”

The fifth anniversary of CiV offers a good opportunity to appreciate this rich contribution of Benedict XVI to the Catholic doctrinal tradition and to note that neither he nor Francis can easily be fit into ideological categories of today’s politics. Indeed, if what we proclaim can be, it probably is not the Gospel of Jesus.

June 27, 2014

Caritas in Veritate, Five Years On (Part 3: Love at the Center)

There is a lot about the content of Caritas in Veritate that is worth paying attention to, and I’m not going to explore it all in this little series of posts. I would mention three in passing before turning to the one I want to focus on here.

First, like Populorum Progressio, the major theme of Caritas in Veritate is authentic human development. And with Paul VI before him, Benedict XVI insists upon a broader understanding of the topic than it commonly receives. He considers the factors that promote development and those that threaten it, covering topics like hunger, economic aid, population, and the participation of the poor in the decisions that affect their lives and well-being. He reiterates the call (made earlier by John Paul II, Paul VI, and John XXIII) for the development of some world political authority.

Second, Benedict’s comments in CiV on the environment are not to be overlooked. Indeed, they are – according to Catholic social teaching expert John Carr – “groundbreaking.” Benedict insists that “the Church has a responsibility towards creation and she must assert this responsibility in the public sphere.” In other words, just as Catholics need to be involved in the legal and social protection of the unborn and of marriage, so they must be actively involved in the legal and social protection of the environment. He reminds us of the harmful consequences of our consumerism upon the environment, and he ties authentic human and economic development with protection of the environment. In one of my favorite passages of the document, he connects the Church’s pro-life concerns directly with its environmental concerns (and so those who think Pope Francis was the first to insist that we consider abortion within the broader context of the Church’s social teaching are mistaken):

In order to protect nature, it is not enough to intervene with economic incentives or deterrents; not even an apposite education is sufficient. These are important steps, but the decisive issue is the overall moral tenor of society. If there is a lack of respect for the right to life and to a natural death, if human conception, gestation and birth are made artificial, if human embryos are sacrificed to research, the conscience of society ends up losing the concept of human ecology and, along with it, that of environmental ecology. It is contradictory to insist that future generations respect the natural environment when our educational systems and laws do not help them to respect themselves. The book of nature is one and indivisible: it takes in not only the environment but also life, sexuality, marriage, the family, social relations: in a word, integral human development. Our duties towards the environment are linked to our duties towards the human person, considered in himself and in relation to others. It would be wrong to uphold one set of duties while trampling on the other. Herein lies a grave contradiction in our mentality and practice today: one which demeans the person, disrupts the environment and damages society.

Third, also notable is the Pope’s sustained attention to business and, in this context, a new papal call for a type of business enterprise that falls somewhere between for-profit and non-profit, for which making a profit and serving the common good are equal priorities.

In additional to all of that, though, perhaps the most significant aspect of Benedict’s teaching in CiV is his insistence on the central place of love in the architecture of Catholic social teaching. Theologian Donal Dorr calls this “the distinctively new element” in CiV, noting (in his excellent book Option for the Poor and for the Earth):

Earlier social encyclicals rightly stressed the fact that our response to issues of poverty and oppression is an obligation of justice and is not ‘merely’ a matter of charity. But now that there is no longer any doubt about that, Benedict sees it as essential to insist that love must animate and permeate all our efforts to create a more just world.

Prior to CiV, Catholic social teaching was lacking something essential. It’s interesting that when I check two of the finest resources published on Catholic social teaching in the past decade – Kenneth Himes’s Modern Catholic Social Teaching: Commentaries and Interpretations and Charles Curran’s Catholic Social Teaching, 1891-Present: A Historical, Theological, and Ethical Analysis — the index of neither of these go-to books includes an entry on love. This is not because their authors ignored it, but because there just was not that much to say about love in CST before Benedict.

Benedict brings love to the foundational place is ought to have in the architecture of that tradition. The Christian pursuit of social justice is not, fundamentally, about carrying out a moral obligation or assuaging our own guilt upon witnessing the suffering of others. For a Christian, it’s not even, at its heart, about making the world a better place. Christians, Pope Benedict writes, are compelled to pursue justice first of all because we have come to know and experience God’s love for us and for the people and the world around us, and we want to live and proclaim that love. Benedict writes:

As the objects of God’s love, men and women become subjects of charity, they are called to make themselves instruments of grace, so as to pour forth God’s charity and to weave networks of charity. This dynamic of charity received and given is what gives rise to the Church’s social teaching, which is caritas in veritate in re sociali: the proclamation of the truth of Christ’s love in society. (n. 5)

This is expressed in particular in Benedict’s distinctive call for economic, social, and political systems marked by “gratuitousness,” that is, by a spirit of generosity, compassion, and unselfishness.

This aspect of CiV is not surprising, since love was a key theme of Benedict’s pontificate from its start. His inaugural encyclical, of course, was Deus Caritas Est (“God Is Love”). Though this encyclical will probably never be listed among the social encyclicals of the tradition, it includes a lot on the Church’s social teaching. You can’t talk for very long about love – it is as though Benedict tells us — without talking about Catholic social teaching. Love is social in nature, so how could you possibly try to? Similarly, you can’t conceive of Catholic social teaching (and shouldn’t be able to) without talking about love.

For this very real and important contribution to Catholic social teaching, a corrective one that deepens that tradition’s connections with the Christian gospel, we owe Pope Benedict a debt of thanks. And we are challenged to form our own understanding and living of the teaching in accord with it.

(I’ll post Part 4 of this series in a few days.)

June 25, 2014

Caritas in Veritate, Five Years On (Part 2: Commemorating Populorum Progressio)

An interesting (though tangential) historical note: If the folks at the Vatican hoped to get people to notice the publication of Pope Benedict’s encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, on its release day that early summer of 2009, they could hardly have chosen a worse day. Dated June 29, 2009, the document was released to the public a little over a week later, on July 7. To put it mildly, the attention of most of the world was elsewhere that day, thanks to wall-to-wall cable news channel coverage of the funeral of Michael Jackson.

CiV is subtitled “On Integral Human Development in Charity and Truth.” It’s a social encyclical — that is, it is on some specific aspect of Catholic social teaching, following in a long line of remarkable modern encyclicals starting with the foundational Rerum Novarum, published by Pope Leo XIII in 1891. Like so many modern social encyclicals before it, CiV pushes Catholic social teaching a few steps forward and applies it anew to an ever developing social landscape.

CiV was intended to mark the fortieth anniversary of Pope Paul VI’s landmark 1967 encyclical on human development, Populorum Progressio. This is itself noteworthy, since almost every social encyclical prior to that was published on an anniversary of Rerum Novarum; for tradition-minded Benedict, the departure was certainly a deliberate choice. Why make it?

Populorum Progressio was a careful exploration of the interconnections between Christian ethics and the economic life of nations. At a time when economic development of poor nations was rising on the priorities of policy-makers around the world, Pope Paul insisted that authentic development is not just about providing money where there is not enough; it must respect and develop the humanity and the dignity of all involved. Paul wrote, “There can be no progress toward complete development of man without the simultaneous development of all humanity in the spirit of solidarity” (n. 45). And that solidarity must be practical. Paul insisted that rich nations must be concerned about poor nations, and express this concern in concrete ways, such as aid, fairer trade relations, and making sure that no people is left behind as development advances.

It’s worth noting that Populorum was greeted (and continues to be regarded) with profound disappointment by Catholics (and others) whose politics were conservative in nature. This is not surprising, since Paul takes direct aim at many basic principles of economic liberalism (which is called “conservatism” is the U.S. today). He said free trade and the laws of the market are not adequate guides in international trade relations; these relations are subject to the principles of social justice. He condemned any economic theory that “considers profit as the key motive for economic progress, competition as the supreme law of economics, and private ownership of the means of production as an absolute right that has no limits and carries no corresponding social obligation” (n. 26).

Not surprisingly, then, the Wall Street Journal called the encyclical “warmed-over Marxism.” Years later, the neo-conservative Michael Novak wrote that it was naive, lacking in humility, and overly emotional.

Pope John Paul II clearly disagreed. In 1987, he took the novel step of marking the twentieth anniversary of Populorum’s publication with a social encyclical of his own, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis. By commemorating Populorum in the way that other popes (including himself, with the 1981′s Laborem Exercens) had commemorated Rerum Novarium, JP2 automatically gave Paul’s encyclical greater prominence and significance in the landscape of Catholic social tradition. (Sollicitudo, for its part, was also rejected by conservatives. William Buckley said it was “heart-tearingly misbegotten.” And the New Republic accused John Paul of making himself “an apostle of moral equivalence.”)

With the publication of CiV, Pope Benedict XVI repeated his predecessor’s commemoration of Populorum. Indeed, Benedict wrote in it that Paul’s encyclical is “the Rerum Novarum of the present age” (n. 8). It’s a strong statement of support for the contents of Paul VI’s encyclical.

As an anniversary marker, though, CiV was late. But some initial delays in its preparation soon seemed downright providential, since they provided the Pope the opportunity to delay it even further with the onset of the global recession in 2008, in order that this new social encyclical could do what many of its predecessors have done so well: apply Catholic social teaching to the developing circumstances of its day.

The result is what theologian Donal Dorr has called “a remarkably insightful and comprehensive presentation of the Christian and Catholic approach to economic activity, to business, and to social justice at the national and international levels.” Indeed, Dorr contends that CiV provides “a richer and more satisfying theology of human development and of social justice” than the earlier encyclical it commemorates.

[Part 3 of this little series on Caritas in Veritate will come in a couple of days.]

June 24, 2014

He can’t wait

I was just looking again at this homemade video of Pope Francis’s roadside stop in Calabria, which Rocco posted the other day. I’ve been moved each time I’ve watched it, by the simplicity and joyfulness of the moment.

But the thing that keeps popping out at me comes at about 00:13 on the timecount. When the Pope’s car stops. What I keep noticing is that the Holy Father barely waits for the car to stop before opening his door. I can picture the driver saying, “Damn, let me stop the car first!” He was not stopping along the road there out of some sense of obligation. That much was obvious anyway. But that door bursting open while the car was still in motion — it says he was sort of busting to get out of there, to get with the people, to be with his flock.

God bless him. And Lord, make us worthy of him.

(Part II on Benedict’s Caritas in Veritate tomorrow.)