C.M. Saunders's Blog, page 2

June 23, 2025

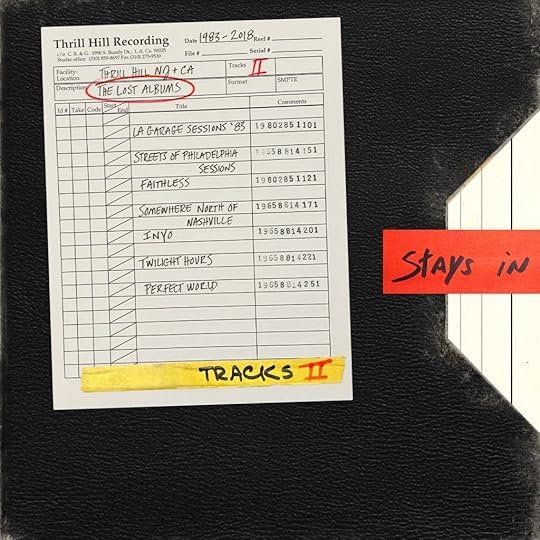

Bruce Blogs #4: Why I won’t be buying Tracks II

When Bruce Springsteen released the first Tracks in late 1998, it was just what fans had been waiting for. A four-disc boxed set consisting of 66 b-sides, outtakes, demos, and unreleased songs charting an alternative map of his career from 1972 up to 1995. If memory serves, I think it cost just under £40. According to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, this would be roughly £75 today. Since then, those archives have been further raided for various other projects, such as the bonus disc of rarities accompanying the Essential Bruce Springsteen in 2003 and The Promise double album in 2010. All this makes me believe that anything worthwhile would have been released by now.

Before I go any further, I should probably reiterate what a huge Springsteen fan I am, and have been for almost four decades. I have bought literally every official release, some unofficial releases, been to see him all over the world, most recently in Birmingham and Cardiff, and even made a pilgrimage to Asbury Park, New Jersey in 1999. His music has provided the soundtrack to my life. For me he peaked with Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town, but for the most part his recorded output has been of a consistently high standard. He has made a few mis-steps, though. Springsteen himself has alluded to making several albums in the nineties that were so bad he could barely listen to them. The Human Touch and Lucky Town albums, two of the few officially released during that decade, are generally considered to be among his less adored, shall we say. Nothing that drew as much ire as the Great Ticketmaster Fiasco of 2022 when ‘dynamic pricing’ saw tickets being sold for thousands of dollars and loyal fans being ripped off left, right, and centre. Of course, The Boss denied all knowledge. It wasn’t as if he needed the money, having sold his entire catalogue to Sony the year before for a reported half a billion dollars.

Which brings me to my issue with Tracks II: The Lost Albums, released this week. And no, it’s nothing to do with his recent poliItical posturing, it’s the sheer cost of the thing. The 83 tracks come spread over either seven CDs for £229.99 or nine vinyl discs retailing at £279.99. That’s a decent chunk or change. It means each CD is being sold at £32.85, and each album at £31.11. Can you imagine the public outcry if Springsteen, or anyone else, tried charging those prices for standard commercial releases? According to Google’s handy AI overview, in 2023 the average cost of a CD in the UK was £10.21 and a vinyl album £26.01. And when dealing with boxed sets, this average price is often driven down because you aren’t just buying a single disc, but multiple units. What makes Bruce, or his record label (Columbia, now owned by Sony), think these songs, which haven’t been deemed good enough for release until now, are worth so much more? I’m sceptical.

I’m not buying it. Neither figuratively or literally. This whole thing stinks. I could stomach paying over the odds for concert tickets, and even being asked to shell out for album after album of patchy material. But this is a bridge too far. Yes, there is the option of buying a condensed single CD or double vinyl version (Lost and Found: Selections from the Lost Albums) for completistst and fans that don’t (or can’t) part with that amount of money, mirroring the 18 Tracks collection of 1999. But even that is overpriced, comparatively speaking (£12.99 for the CD and £37.99 for a double vinyl) and where 18 Tracks came with three tracks not included on the boxed set. That in itself was construed by many as a cynical move as in the days before streaming and selective downloading, it was purely designed to make fans fork out for a whole album’s worth of material when all they really wanted were the three ‘new’ tracks. The thing I’m struggling most to reconcile here is the fact that the working class hero, man of the people image Springsteen has spent a career nurturing, is in danger of crumbling to dust. If it ever really existed. Let’s not forget this release comes just prior to yet another presumably not insignificant payday with the biopic Deliver Me From Nowhere scheduled to hit screens this year. And he’s on the road again. Those bucks are rolling in.

Some titles here will already be familiar to many having previously been released in some form or other; Follow that Dream, County Fair, Johnny Bye Bye, My Hometown, Shut out the Light, Secret Garden. Plus, there are a few more with titles so bland and generic you feel tired of them even before you’ve heard them. How excited can we get about a collection of outtakes of outtakes of outtakes? Most of us are still recovering from his cover of Do I love You (Indeed I do). This feels exploitative. Like a barely disguised cash grab. If in doubt, just look at that cover art. What art, I hear you say. No effort has been made whatsoever. That’s exactly my point.

I fear Bruce, as much as I love the guy, might have gone to the well too many times and perhaps these ‘lost’ albums should have stayed lost.

June 11, 2025

The Incomplete Sneeze

I am pleased to announce that my sci-fi short story The Incomplete Sneeze is included in A Twist on Time, the new time travel-themed anthology on Smoking Pen Press. I have worked with SPP before, when they included Down the Road in Vampires, Zombies, & Ghosts, another entry in their Read on the Run series.

From the cover:

You won’t find anything reminiscent of H.G. Wells, or of the Doctor Who series. Rather, you’ll find some unintended jumps in time, without any machines or devices. You’ll find some questionable means of travel. And – in contrast to the ‘standard’ rule that you cannot/should not change the past, you will find people from the future who come back with the goal of changing the future, and you’ll find efforts at do-overs, both successful, and not so successful.

What’s the Incomplete Sneeze about? Well, in the mornings I sometimes have sneezing fits. Some kind of allergy, I suppose. An old girlfriend once described sneezing as like having an orgasm in your head, which is a pretty unique description and not far off the mark. Anyway, I began to wonder what might happen if I fell through a wrinkle in the universe and teleported every time I sneezed. In my mind, this somehow got tied up with the mystery of the Somerton Man, when a ‘well-dressed’ gentleman was found dead on a beach in Australia and nobody could work out who he was, and a story was born.

A Twist on Time is out now.

June 1, 2025

The Research Process

Any writer will tell you that research is a crucial aspect of the craft. But it’s importance is elevated in historical writing, which often stands or falls in the small details. Your work has to be factually accurate, or things quickly fall apart and it loses all credibility. At the very least you’d be called lazy, and probably a lot worse. Readers can only suspend belief so much, and if inaccuracies find their way into the text it jars and the whole house of cards is at risk of falling down. For example, it’s no good writing a story set in California in the year 1879, taking time to carefully construct the scene and introduce the characters, then have one of them use a Lee Enfield rifle, which didn’t come into widespread use until 1895 and even then was mostly issued to British soldiers with very few finding their way over the pond until much later. Not every reader would know this, but I’m willing to bet a good many would. Weaponry plays a vital role in my new novella, Silent Mine, the first in a series of stories starring the same protagonist Dylan Decker, as it does in most Westerns, so it was absolutely vital to get it right. Other minor details I had to address for the sake of authenticity were what the average general store might sell, the price of a shot of whisky, and the measure it came in.

Part of the inspiration for Silent Mine was the video game Red Dead Redemption 2, an open world adventure role play set in the Wild West. The game is impressive in many ways, not least the level of detail it contains. It’s also impeccably researched, with several elements finding their way into the book. One example is the practise of carving an X into bullets to create an early form of expansion ammunition, which was just too good not to use. Once armed with a scrap of information as a leaping off point, it was off to the internet to find out more.

When carrying out research, I think it’s important to forget everything you think you know and try to approach the topic with fresh eyes. There are a lot of common misconceptions out there, especially about the so-called Wild West, that aren’t strictly true. For example, if you watch any Western movie you’d be forgiven for thinking that people were getting killed left, right, and centre. But the fact is that the murder rate was lower back then than it is in most modern cities in the same location, even taking into account the higher population. From what I can make out, the dramatic gunfights and face-offs that were the bread and butter of the genre are a Hollywood invention, exceptionally rare IRL. Who on earth would risk death when it would be safer and easier to bide your time and shoot someone in the back when they weren’t expecting it?

In addition, relations between settlers and Native Americans weren’t nearly as fraught as Hollywood would have us believe. Sure, there were flashpoints, and some pretty ugly historical events, but generally speaking the two groups just wanted to make the best lives for themselves, with each using the other to their best advantage. There was also a lot more diversity than is generally portrayed in the movies. Cowboys immigrated to the US from all over the world and spoke every language under the sun. At least the famed Spaghetti Westerns of the sixties and seventies were on point in that respect. I did take a few liberties. I call it artistic license. Dylan is a comparatively recent name, popularized by the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas in the mid-20th Century so it’s unlikely there were many cowboys using it. And though a ‘sour toe cocktail’ is a real thing (I promise!) again, it wasn’t around in 1879 though probably should have been.

There’s no denying that the whole art of research is much easier in the internet age. Twenty years ago I wrote a book about a Welsh football (soccer) club, and my research entailed travelling to a major library every morning and manually scanning countless reels of microfilm. When I found something of interest I scribbled it down in a notebook. These days, we literally carry the sum of mankind’s knowledge around on a device we keep in our pockets (and use it to look at pictures of cats, as the meme goes). But you still have to know what you’re looking for, and there’s a lot of misinformation out there to sift through. Sometimes it can be like looking for a nugget of gold in a sea of sludge. And with internet sources being notoriously unreliable, you always have to check that what you’ve found is the real deal and not a chunk of fool’s gold.

Silent Mine is out now

This post first appeared on the Undertaker Books website.

May 18, 2025

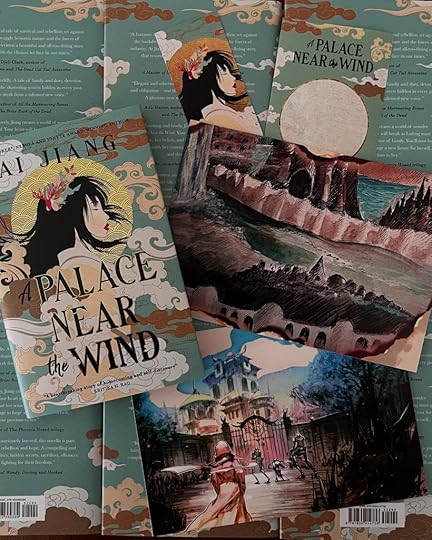

Book review – A Palace Near the Wind by Ai Jiang

I have long been fascinated by Chinese culture. It’s all those layers and hidden meanings, then the hidden meanings behind the hidden meanings. You think you grasp something, then look at it a little deeper, and realise what you were ‘grasping’ was only the tip of the iceberg. You weren’t wrong. You just weren’t seeing the whole picture. This concept permeates virtually everything, but is particularly prevalent in fiction. Words are building blocks, after all. The problem is, Chinese doesn’t translate very well to English. The surface meaning usually carries over and can be translated in a literal sense, but many of the nuances and deeper connotations are lost. Ostensibly Chinese is quite a direct, pragmatic language, but the written word works on multiple levels.

Take A Palace Near the Wind, for example, the first in the Natural Engines series, by Canadian/Chinese writer Ai Jiang. The plot follows Liu Lufeng, a Feng princess destined to become the next bride of a king with which her people have made a binding agreement. With bark faces, branches for arms, and sap running through their veins, the Feng people are more tree than human, and part of the very land on which they exist. However, they are under threat of human expansion, the negotiation of bride-wealth being the only way to delay the destruction of their home. Lufeng decides that it ends with her, and come her wedding day, plans to kill the king and set her people free. But while preparing for the ceremony, she learns that things are not quite as they seem.

Ostensibly, this is a tale of high fantasy. But I have also seen it described as folk horror, science fiction, and even eco-fiction, which is a new one on me. True, there is a message here, and poignantly, it is even dedicated to ‘Mother Nature and all her unwilling sacrifices.’ That is also possibly a little nod to another of the book’s themes, because alongside the threads of duty, hope, discovery, and coming-of-age, are darker themes, such as rebellion, fear, and sacrifice. It culminates in the realisation that the way we percieve things is often skewed or distorted, and sometimes coloured by our own expectations or prejudices. The world-building is enchanting, and the word selection exemplary. But as other-worldly as it is, you are made to feel right there with Lufeng, and even though she’s (at least) half tree, you can’t help rooting for her (sorry).

Like a lot of outstanding fiction, A Palace Near the Wind lends itself to many genres but ties itself to none. This in itself instills a vague sense of displacement or lack of belonging within the reader, something mirrored throughout the book. You can’t help but wonder whether this is a conscious or subconscious effect of the author’s background. The duality of belonging to two places at once, of being the same yet different, reconciling the doubts and insecurities that can arise when one considers their role in the world, balancing the desire to fit in yet stand apart, and knowing when to compromise and when to fight.

I first became aware of Ai Jiang’s work several years ago when we both had stories in the same anthology. Back then she was a student in Edinburgh, and though just starting out, you just knew she was going to be something special. The short story Give me English (currently being novelised, I believe) was my gateway. You can check that out here. I was curious to see how she would adapt to long-form fiction. Her work is usually sharp and precise, but very intense and filled with tiny little daggers. She barely wastes a syllable, honing each word until it hits just right. I wanted to see if she could or would carry this style through, or whether a novel, albeit a short one, would provide more room to explore and elaborate. This is probably one of those timeless books that you could read again in a couple of years time and take something different from it. I’ll let you know if that turns out to be true.

A final word needs to go to the packaging and artwork. They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but it’s impossible not to when the cover is this beautiful. Rarely do you see such meticulously appropriate artwork accompanying anything, let alone a book.

A Palace Near the Wind is out now on Titan Books.

May 13, 2025

RetView #84 – Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972)

Title: Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things

Year of Release: 1972

Director: Bob Clark

Length: 87 mins

Starring: Alan Ormsby, Anya Ormsby, Valerie Mamches, Jeff Gillen, Paul Cronin, Jane Daly, Bruce Solomon

Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (also known as Revenge of the Living Dead, Things from the Dead, Cemetery of the Dead, The Siege of the Living Dead, and Zreaks) is an iconic piece of work co-written and directed by Bob Clark, who would go on to direct Deathdream (1974) and the classic frat comedy Porky’s. Riffing off Night of the Living Dead (1968), the script was written in 10 days and the movie shot in 14 on a budget of just $50,000, with most of the people working on it being college friends making it a true labour of love. Most of the cast were not even trained actors, with only a select few going to to have modest careers in TV or cinema. Also, this must be one of the very few zombie movies starring a married couple, Alan and Anya Ormsby who’s characters, hilariously, are also named Alan and Anya. Nod, nod, wink, wink. The quips and one-liners come thick and fast (“What a bunch of stiffs!”). At least, they do until the shit hits the fan.

The story follows a theatre troupe (“I do have talent when I have a good part!”) who travel by boat to an island off the coast of Miami that is mainly used as a cemetery for criminals, for a night of campy fun. When they arrive, their director Alan (Ormsby), a twisted, sadistic individual, tells the motley crew of actors, whom he refers as his ‘children’, stories about the island’s grisly history in a concerted effort to unsettle them. He also digs up the corpse of a man named Orville, which is certain to make any party go with a bang. The names written on the styrofoam tombstones, by the way, are the names of various crew members.

“They’re having trouble all over the world with graverobbbers, ghouls, and people breaking into cemeteries.”

“But we’re the graverobbers. Who’s going to bother us?”

“Nobody but demons.”

And zombies, as we are soon to discover.

Eventually, Alan leads the group to a cottage where they are supposed to spend the night, and then proceeds to get robed up and prepare the group for an ancient ritual to summon the dead. Probably not the smartest move when you’re on an island off the coast of Miami that is mainly used as a cemetery for criminals, but okay then. When some of the group aren’t so keen (understandably) he threatens them with the sack, which I am pretty sure would be a breach of some ethical code or other these days, but this was the seventies. Alan’s bullying and cheap jokes soon stop when the gang realise the ritual they performed had worked, and the entire island is now swarming with freshly reanimated zombies. It kind of makes you wonder what they expected to happen. Even for a low-budget seventies horror comedy film, “They seem pretty slow. Why don’t we make a run for it?” has to be one of the dumbest lines ever uttered.

In a desperate attempt to get themselves out of the mess they had created, the group attempts to perform another ritual to return the zombies to their graves. And it works! For a bit. However, they neglect to return Orville to his grave, prompting the zombies to re-emerge and ambush the group as they leave the house. Alan and Anya retreat back inside, and in a last ditch effort to save himself, despicable Alan throws Anya to the zombies and locks himself in the bedroom where he left Orville’s corpse, not realising Orville is now a zombie, too.

In these #RetView posts I try to keep spoilers to a minimum and not to discuss plot holes or endings. I’m not here to be a killjoy, and my hope is that readers will seek these films out themselves. On this occasion, though, I feel I have to mention it. The zombies get on the boat, see. The boat the group had taken to the island. As the zombies board it, you can see the inviting lights of Miami twinkling in the background, the implication being that the zombies will soon enter the mainstream, so to speak. But… who is going to sail the boat? Sailing a boat is a tricky business, or so I imagine. These zombies are shambling husks that can barely walk. I doubt very much any of them retain enough brain function, let alone dexterity, to captain a boat across a choppy section of water. I know I’m probably pedantic but as the credits rolled all I could think was, “Shit! The zombies got on the boat!” which was, I suppose, the desired effect. But this was quickly followed by, “Oh, it’s okay. they won’t get far. We’re good.”

Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things is currently rocking a 42% rating on review site Rotten Tomatoes and in reviewing the later DVD release, Bloody Disgusting said: “[This] is well worth your time if you haven’t gotten around to it yet [and] really should be held among the top zombie movies of all time.” Meanwhile, the website 100 Misspent Hours was less generous, saying, “The biggest problem with Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things is that it’s an 85-minute zombie movie in which the zombies don’t turn up until minute 64.”

Bob Clark was said to have been considering a remake, but plans were curtailed when his Infiniti I30 was hit by a drunk driver in April 2007. Unless, of course, Alan Ormsby decides to raise him from the dead. Since then, other rumours of a remake have circulated, but none have so far come to fruition. It is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

Trivia Corner

Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things, a track on Finnish heavy/doom metal band Wolfshead’s 2017 album Leaden, is based on the movie.

April 20, 2025

The Editors

During my two-decade career writing for magazines, I have worked closely under several dozen different editors (1). Sometimes our working relationship lasts a couple of weeks, other times it lasts for years. There are a few I have been working with in one capacity or another since the very beginning. After a while, for better or for worse, you begin to identify certain character traits that distinguish them from each other. If you’ve ever worked for a magazine or newspaper, no doubt you’ll be able to put almost every editor you’ve ever had into one of these handy boxes.

The steady hand

In my opinion, the best kind of editor. Unfortunately this is also the rarest, and a dying breed. Usually older and more experienced, they are calm under pressure and nothing seems to phase them because they’ve seen it all before. They are always available but never interfere, preferring to let the separate departments do their jobs. They see their role as more of an organiser and overseer and they step in only to prevent things going into meltdown, after which they calmly retreat again. Until the next crisis.

The up n’ comer

These guys are rarely equipped for the job and are very often thrown in the deep end, usually as a cheap option by a publishing company who don’t want to pay a real editor (like the aforementioned Steady Hand) to do the job. Consumed by arrogance and an overbearing sense of self-importance, the first thing they do is try to impose their authority by handing out jobs to their incompetent mates and making radical changes to the publication, forgetting the fact that readers hate it when you make radical changes to the publication. Destined to fail, they invariably do and resurface years later driving an Uber or something.

The Trail Blazer

This kind of editor once experienced huge success somewhere, probably more through luck than judgement, and been living off the proceeds ever since. They are often brought in to spearhead a new launch or in a last-ditch attempt to boost circulation at an ailing publication. It rarely works, and the job is usually soon reduced to putting out a sequence of fires. He or she will be down the road in six months, but don’t worry, because they did that thing at that magazine that one time, they won’t have any trouble finding alternative employment.

The Dictator

Usually suffering from some kind of delusional mental disorder, these people want, no, NEED, to control every aspect of the operation, striving to micromanage every little detail and extending their influence into areas that have literally nothing to do with them. They think they know everything, even when they clearly don’t, and want to be CC’d on every internal email so they never miss a thing. Worst of all, they flatly refuse to even entertain anybody else’s opinion thinking it would somehow undermine their authority. They see the publication they work for as their baby, and want to dress it, bathe it, and feed it with no input from you, thank you very much. The problem is, they are usually incapable of doing so and the baby ends up starving to death.

The Lazy Allocator

For some reason, these guys think being an editor simply means taking home the most money for doing the least amount of work. Experts at emotional manipulation and gaslighting, everything they do is geared towards making their jobs easier and they don’t care if it makes yours harder. They allocate all their duties to other people, and get the work experience kid to fill in on the picture desk, sub the freelancer’s work, and write five features a week. To add insult to injury, in their final report they’ll give the overworked workie a score of 2/10 and say they should have tried harder. To fill their time they arrange meetings with people who are far too busy to have any more meetings because of their increased workloads, and fixate on tiny details that make absolutely no difference to anyone.

The Lifer

Usually found in the B2B or on ‘niche’ speciality titles, these people have been quietly devoted to the job, and the industry their publication serves, for most of their working lives. By now, their knowledge pool is so deep and vast that recognised industry experts call them for advice. Seriously, what Justin doesn’t know about Korean-made kitchen worktop surfaces just isn’t worth knowing. It’s that simple. The highlight of their year is the annual worktop surface conference in Milton Keynes. I often wonder whether they work for this particular title because of their affinity for the topic, or whether they have an interest in the topic because they work for this title. It’s like the chicken or the egg paradox.

(1) For the purpose of this article, when I use the word ‘editor’ I am referring to traditional magazine and newspaper editors, of which there are still some left. Not the kind of ‘editor’ an indie fiction writer might send their stuff before they self-publish it on Amazon. That’s a different thing, and we should really have a different word for it but we don’t because I guess we haven’t progressed that far as humans yet.

April 13, 2025

The Screaming Man

I am happy to report that my short story, The Screaming Man, has been included in Horrific Scribblings. The brainchild of L Andrew Cooper, HS is an expanding online archive of dark short fiction (and some poetry) by various authors who share the outlet’s dedication to the provocative, scary, and strange. As Andrew explains, “there are no issues like a magazine. Instead, new stories are published on a rolling basis and it has ‘Exhibits’ that feature groups of works put together because they have commonalities: themes, subgenres, image patterns, etc.”

The Screaming Man, about a man visiting his old school for the last time, is built on sentimentality. Sort of. What he doesn’t see himself doing that afternoon is stumbling across the answer to a mystery that has haunted him since childhood. Andrew says the story is about, “the ways nostalgia and memory affect time, perhaps leading to a literal monster from the past. From the beginning, Saunders peels back layers of time like onion skin, giving the story formal adventurousness mostly masked by the easygoing narrative voice.”

Read The Screaming Man FREE.

March 15, 2025

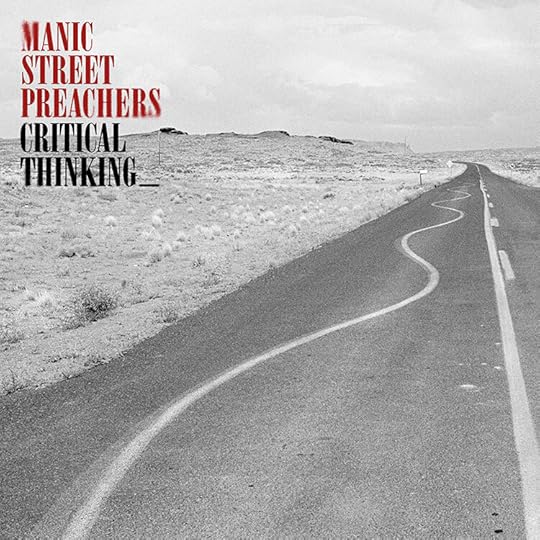

Manic Street Preachers – Critical Thinking (review)

The Manic Street Preachers are one of those bands whose music may resonate more at some times than others, but have remained one of the few constants in my life. They started strong back in the early nineties with Generation Terrorists, and were an integral part of the swaggering Cool Cymru scene that truly put Wales on the pop culture map. Since that glorious heyday, the quality of material they’ve put out has varied wildly and apart from the odd banger, they haven’t bothered the charts much. Apart from a brief period in the late nineties, they have generally been on the periphery of the mainstream, in that adjacent space they carved out for themselves so deliberately where they are free to offer off-centre political comment and their unique brand of Pound Shop philosophy, but largely unencumbered by commercial pressures. Through it all they have managed to maintain a sizeable cult following, so like a lot of so-called heritage acts still releasing new material (most of them don’t) now try to cater for the fanbase by being the versions of themselves they think most people want them to be. Sometimes it’s comforting, sometimes it’s passable, and sometimes its borderline embarrassing and they come across like a parody of themselves. Coming immediately after reissues of earlier albums Know Your Enemy and Lifeblood, in interviews the band have alluded to this album being a hybrid of those two endeavours. Perhaps as a consequence of being forced to retrace their steps so often, introspection is never far away in the life of the Manics, circa 2025.

Critical Thinking is filled with every Manic-ism you can think of, and more besides. The soaring choruses, the sloganeering, the lyrics concerning obscure painters and war photographers perpetually wavering between defiant and morose, the odd plinky plonky piano. Seasoned bands are generally less experimental these days, and just give the fans what they want. Times ten. Or in this case, times twelve as that’s how many tracks it contains. In doing so, they climb a few rungs on the fame and riches ladder because their popularity goes up a few notches. “Albums are a reflection of where your mind is at – certainly in the Manics’ world,” Nicky Wire told NME just prior to the release of this album, before defining ‘critical thinking’ as the power to reject by not always going with the flow. This ingrained non-compliance has been a near-constant theme in the Manics’ work for decades now, to such an extent that it has become a trait in itself. Each of their albums feature a quote, chosen by the band, which aims to add context to the overall project. This time it’s ‘I am a collection of dismantled almosts’, by US poet Anne Sexton who often addressed mental health in her writing before committing suicide at the age of just 45. In clarification, Wire says “If everyone had the same amazing fucking benefits I had when I was growing up – the music that was around, the parents that I wish everyone could have – it wasn’t anything other than working class but it was just so culturally-enriched. It’s all about critical thinking – trying to re-evaluate who you are and why you like those things.”

That might not be in line with everyone’s interpretation of the phrase ‘critical thinking’ but ‘everyone’ doesn’t matter. This, the band’s fifteenth studio album, comes four years after their last, the Ultra Vivid Lament became their first UK number one since This is My Truth, Tell me Yours topped the charts way back in 1998. The most memorable thing about that particular release was that it wasn’t very memorable. Here, we are dropped right in the middle of some kind of Clash/Dead Kennedy’s mash-up with Nicky Wire’s sweary, deadpan, spoken word delivery layered over the top. This might be what would happen if New Order covered Blur’s Park Life. It’s an intense, and slightly weird start, which, thankfully, acts as a hors d’oeuvre. It isn’t long before the album’s jewel, recent single Decline and Fall, spills forth, the sweeping tones and anthemic chorus bringing to mind peak Manics. That early highlight is quickly followed by another, Brushstrokes of Reunion, written by James Dean Bradfield about an oil painting by his now-deceased mother, and the emotive power it still maintains over him. Moving stuff. These two tracks alone exemplify everything that is great about this little group of survivors from Blackwood.

Next up is Hiding in Plain Sight, a perfect example of one of those jaunty little numbers with paradoxically depressing and mournful lyrics the Manics do so well. This track works as a fitting couplet with People Ruin Paintings, which will invariably sound suspiciously like something else you’ve heard but can’t quite put your finger on. Not that there is anything wrong with that. I think it’s called ‘paying homage’ and Oasis have made a career out of it. The track Dear Stephen was ostensibly inspired by a postcard sent to Wire as a teen from Morrissey at the request of his mother after he was too ill to attend a Smiths gig, and a sleeper hit here (were it not for the subject matter) might be Being Baptised. Elsewhere, Out of Time Revival sounds like classic late-period Police with maybe a hint of Talking Heads, while album closer OneManMilitia is defined by a breezy, country-tinged guitar solo.

You’ll find influences laid bare throughout the album, something the Manics have never shied away from. They have always been a product of their environment. But Critical Thinking is a remarkably consistent effort, especially after repeated listens. The quality doesn’t drop much throughout, even if it gets slightly repetitive towards the end and you find yourself yearning for a You Love Us or a Stay Beautiful to shake things up a bit. Nope. You should be so lucky. Instead, it’s all a bit polished and safe. No doubt, it will please the diehards. Hell, it even pleased me for a while and I’m not even a diehard. As ever, there is some exceptional lyricism on display veering between insightful and profound. One of my favourite lines comes from Late Day Peaks; “There’s no shame in a smaller world, become an expert in what you observe.”

One thing about album-making the Manics (and most other artists) have adapted to over the years is brevity. Albums in general now tend to be tighter, more focused, and shorter. Unless you’re Taylor Swift, of course. Mercifully, bloated 72-minute albums full of spaced-out, mid-tempo plodders, are a thing of the past. The record-buying (or, more accurately, music-consuming) public just don’t have time for it. With Critical Thinking it sounds like the Manics have finally got the balance right, and they just might deliver gold.

Critical Thinking is out now on Columbia Records

March 2, 2025

Fish @ Bristol Beacon, 26/02/25

Early Marillion made music that had the power to transport you somewhere else, and the albums Misplaced Childhood (1985) and Clutching at Straws (1987) still stand as two of the best of all time, the music itself perfectly complemented by Mark Wilkinson’s Jester art which was an integral part of the overall project in much the same way Eddie is a part of Iron Maiden’s legacy. However, after the live album The Thieving Magpie (1988) frontman Fish parted company with the rest of the band acrimoniously. Both entities continued to put out new music, some of it pretty good, but neither would ever come close to hitting the creative and commercial heights they scaled when they combined their powers. This is being billed as Fish’s farewell tour, dubbed The Road to the Isles, before he decamps to the Outer Hebrides to live out his retirement. “The UK nights are going to be awesome indeed with every venue holding something unique and promising so much for everyone both on and off stage,” he recently after a run of European dates. “To be retiring on this wave is a wonderful feeling and I cannot adequately express how much this all means to me after over 40 years in the music business performing on stages across the world.”

In other pre-tour interviews, Fish vowed to switch up the set-list on a regular basis to keep things fresh. After all, he has a catalogue of eleven solo albums to cover, not including compilations, live albums, or the four he recorded with Marillion. Therefore, it was no great surprise when the show kicked off with Vigil, the very first track from his very first solo album, which segued neatly into Credo, the ‘big single’ from his second album, Internal Exile. From there, things got a bit more unpredictable. I thought his final studio album, 2020’s Weltschmerz (German for ‘world weariness’), would be well represented, but that didn’t turn out to be the case. In face, I don’t think he performed a single track from it, which was just plain weird. Instead, after an animated Big Wedge, Shadowplay, Cliche, A Feast of Consequences, and a stunning Just Good Friends, came the first big surprise of the night – the Marillion standard Incubus from the Fugazi album, which Fish wrote the lyrics for as he did most of the old Marillion material. It was a strange choice. I thought if he was going to play anything from this period it would be Script for a Jester’s Tear, or maybe one of the singles. The bulk of the remaining set was taken up by a near-30 minute rendition of the Plague of Ghosts suit of songs from 1999’s Raingods and Zippos album. That “make it happen” refrain always reminds me of Oasis, but that’s hardly Fish’s fault. If anything, we can blame the Gallagher brothers for that.

The main encore kicked off with A Gentleman’s Excuse Me, another cut from his debut solo album. Given this is his retirement tour, the lines “Can you get it inside your head I’m tired of dancing?” seem to carry a little extra weight. This was followed by the Misplaced Childhood-era heavyweight triumvirate of Kayleigh, Lavender, and Heart of Lothian, the guitarist doing a damn fine Steve Rothery impersonisation throughout. It has to be said, these songs, despite being more than 40-years old, have not only stood the test oif time but never been topped by either Fish or Marillion. The band Fish has assembled for this tour, mostly made up of old acquaintances, didn’t miss a note, even if Fish did from time to time (a consequence of being a 66-year old touring musician). He might have trouble hitting the high bars, but he more than makes up for it in showmanship and sheer stage presence. The songs were interwoven with stories and bursts of humour which proved beyond doubt how good a raconteur he is. Things got pretty emotional toward the end, the set running past the 10pm curfew and totalling well over two hours. And the end really did feel like a goodbye.

Bristol Beacon (previously known as Colston Hall, but let’s not talk about that) is a superb venue. Designed as a theatre and first opened in 1867, in its current guise it has a capacity of 1,800 spread over three tiers making it perfect for intimate, emotive nights like this. I watched from the stalls. I love it up in the stalls. You get a great view, it’s pretty chilled because all the proper fans go on the floor, and the acoustics are phenomenal. The venue itself is steeped in rock history, having previously played host to the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Queen, David Bowie, Iron Maiden, Bob Marley, and the Who. Legend has it that during a gig in November 1964 a bunch of upstarts called The Beatles were flour-bombed by some students.

That is so Bristol.

Enjoy your retirement, and thanks for all the Fish.

February 13, 2025

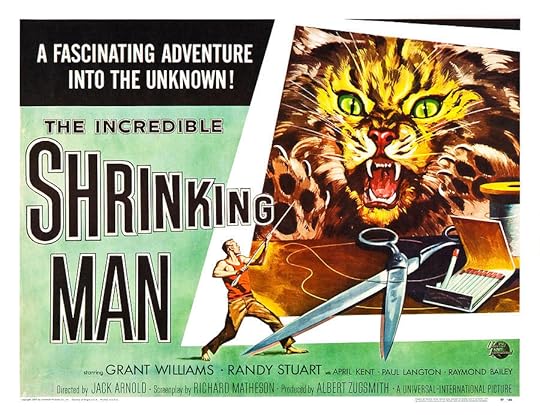

RetView #83 – The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957)

Title: The Incredible Shrinking Man

Year of Release: 1957

Director: Jack Arnold

Length: 81 mins

Starring: Grant Williams, Randy Stuart, April Kent, Paul Langton, Raymond Bailey

Like The Blob (1958) and The Giant Claw (1957), The Incredible Shrinking Man is yet another movie that attempted to cash in on cold war paranoia. It was based on a Richard Matheson book, who expanded it into a screenplay with the help of Richard Alan Simmons. Unusually, the novel and the screenplay were produced concurrently, and the film was already into its second month of production when the novel was published by Gold Medal Books in May 1956.

The movie is told through the viewpoint of the narrator, Robert ‘Scott’ Carey (Williams) who, whilst chilling out on a boat one day with his wife Louise (Randy Stuart, who’s actual name was Elizabeth), is enveloped in a strange mist. Months later, he realizes that his clothes no longer fit and suspects he must be slowly shrinking in size. Understandably concerned, he visits a local quack, who at first is dismissive insisting, not unreasonably, that people are actually taller in the mornings and shrink as the day goes on, as compression on the vertebrae makes you slowly decrease in height. It soon becomes apparent, however, that Scott’s problems are far more acute than that. The doctors are baffled and he becomes a medical curiosity, gaining fame as the ‘incredible shrinking man.’ But all the attention only emphasises his worries and speeds up his mental deterioration. Eventually, he is reduced to living in a doll’s house where he comes under attack from Butch, the family cat. By this point, you can’t help but feel sorry for the little guy. I mean, he’s already been through a lot. But as a result of his battle with Butch he finds himself regaining consciousness in the basement while everyone thinks he perished at the claws of Butch. As if that wasn’t enough, next he has to fight a massive spider, which comes to represent “every unknown fear in the world,” his own hunger, and his own fear. When the basement is flooded, Louise goes to investigate but Scott is so small she can no longer see or hear him. Eventually, she leaves the house and, after killing the spider with a pin (thereby slaying his own fears, as the analysis would have it) Scott becomes so small he is finally able to escape the confines of the basement by simply climbing through one of the holes in a perforated window screen. In a strangely upbeat ending (another was filmed where Scott returns to his original height, but this is the one that made the final cut), Scott seems to accept his fate and looks at the future with a newfound sense of optimism because, although medical science can’t save him and this new world will be full of new challenges to navigate, he knows that no matter how small he becomes, “There is no zero” and he will still exist.

Many innovative techniques and special effects were used during filming. For example, shots featuring Louise were taken against a black velvet backdrop and then composited with shots of Scott on an enlarged living room set. Their movements were then synchronized so they appeared to interact with each other. An oversized dollhouse was constructed for Scott, and food was used to ecourage Butch the cat to ‘attack.’ Jack Arnold, who had previously directed such classics as It Came from outer Space (1953) and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) initially wanted Irish actor Dan O’ Herlihy to play Scott. But O’Herlihy turned down the role, prompting Universal to sign Williams instead. Production went over budget and filming had to be extended as certain special effects shots required reshooting and Williams was constantly being injured on set die to the overly-physical action sequences.

Upon its release, the Monthly Film Bulletin praised the film, and declared it, “A Horrifying story that grips the imagination throughout. Straightforward, macabre, and as startlingly original as a vintage short story.” Meanwhile, a contemporary evaluation by Ian Nathan of Empire magazine calls it a classic of 1950s science fiction films, noting how everyday objects found at home are “transformed into a terrifying vertiginous world fraught with peril. A confrontation with a ‘giant’ spider, impressively realised, as are all the effects, for its day, has become one of the iconic image of the entire era.”

The Incredible Shrinking Man spurned it’s own sub-genre, as movies like the Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) and the Amazing Colossal Man (1957) soon followed, and Matheson scripted a sequel called the Fantastic Little Girl, which had Louise returning to the house where, naturally, she begins to shrink. However, the script was deemed inferior and the movie was never made. The script was, however, published in its entirety in the book Unrealized Dreams in 2005. A quasi-sequel (or a parody, depending on your point of view), The incredible Shrinking Woman, directed by Joel Schumacher of Lost Boys and Flatliners fame, eventually appeared in 1981. A new adaptation of the original was announced in 2013, with Matheson writing the screenplay with his son. However, Matheson the elder died on June 23rd of that year and things have been eerily quiet ever since.

Trivia Corner

While trying a way to film a scene involving giant raindrops landing, Arnold recalled when he was a child finding condoms in his father’s drawer. Not knowing what they were he filled them with water and dropped them. The director then ordered about 100 condoms to be filled with water and placed on a treadmill so they would drop in sequence.