John D. Rateliff's Blog, page 67

January 16, 2020

A Day of Mourning

So, today Christopher Tolkien died, full of years.

He was the last of the Inklings, as well as one of the few remaining combat veterans of World War II.

He will be missed -- all the more so as time passes and the magnitude of his achievements come to be fully appreciated.

I'm glad I got to meet him,

both humble and proud that he entrusted me with editing one of his father's works,

and always delighted when a letter from France would arrive at certain intervals, addressed in the most beautifully legible handwriting I've ever seen.

The world is a sadder place now that there will be no more of these.

He was the last of the Inklings, as well as one of the few remaining combat veterans of World War II.

He will be missed -- all the more so as time passes and the magnitude of his achievements come to be fully appreciated.

I'm glad I got to meet him,

both humble and proud that he entrusted me with editing one of his father's works,

and always delighted when a letter from France would arrive at certain intervals, addressed in the most beautifully legible handwriting I've ever seen.

The world is a sadder place now that there will be no more of these.

Published on January 16, 2020 22:11

January 13, 2020

Anatomy of Authors

So, thanks to friend Stan for the loan of a new book of cartoons, just out from Kickstarter:

ANATOMY OF AUTHORS by Dave Kellett, which gently lampoons a wide array of authors (everyone from Austen to Stan Lee). And being a Tolkienist, naturally the first thing I do when picking up a book like this is to look to see if Tolkien's in it. And he is, right on the front cover in fact, which he shares with Shakespeare, Poe and his raven, Angelou, Austen, and Stan Lee. The back cover goes this one better and reproduces the whole Tolkien entry as well as images of Agatha Christie, Douglas Adams, Sun Tzu, and Phillis Wheatley.

I'm happy to say I know who all the fifty-two authors* included, though I'll admit there were some I didn't recognize from the illustration (like Adams -- the towel and cup of tea shd have been dead giveaways). And I confess there are some of these who I've never actually read.

Still, forty-two out of fifty-two's not bad.

If you're a purist, be warned that Kellett's goal is to amuse and he feels no compunction about making stuff up. The people he presents are based on legend, not real life, though there are factual underpinnings when he finds these funny enough. Nor is he too proud to go for low-hanging fruit: his Tolkien entry includes a joke about Tolkien's grocery list.

Interestingly, his illustrations are more true-to-life than his text. Tolkien for example holds a book (BEOWULF) in one hand and a bar glass filled with some frothy foamy drink (labelled THE EAGLE & THE CHILD) hoisted in the other. He's also smoking a pipe at the same time: clearly a multitasker.

As I said, this was a Kickstarted project. I don't know if it's available to those of us who missed the subscriber deadline, but you can find more information here:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/smallfish/anatomy-of-authors

And, on the left, you can see the ANATOMY OF AUTHORS cover (you might have to scroll down a little).

Plus if you poke around a bit on his website you'll find Kellett also offers a few posters and a pin for Gandalf Airlines, whose motto is Fly You Fools .

--John R.

*Kellett's definition of author is a generous one, including not just Tolkien and Lewis (C.S.) but Nietzsche, Seuss, Rod Serling, and two Chekovs

current weather: cold. snowing (the first big storm of the season). A good time to stay in with the cats.

current music: Helen Reddy's Greatest Hits (dug out because of the recent news of the ERA, no doubt)

current reading: another book on ancient Egypt, Kidnapping chapter of a Lindbergh biography

current audiobook: VOODOO HISTORIES by Aaronovich (a history of conspiracy theories)

ANATOMY OF AUTHORS by Dave Kellett, which gently lampoons a wide array of authors (everyone from Austen to Stan Lee). And being a Tolkienist, naturally the first thing I do when picking up a book like this is to look to see if Tolkien's in it. And he is, right on the front cover in fact, which he shares with Shakespeare, Poe and his raven, Angelou, Austen, and Stan Lee. The back cover goes this one better and reproduces the whole Tolkien entry as well as images of Agatha Christie, Douglas Adams, Sun Tzu, and Phillis Wheatley.

I'm happy to say I know who all the fifty-two authors* included, though I'll admit there were some I didn't recognize from the illustration (like Adams -- the towel and cup of tea shd have been dead giveaways). And I confess there are some of these who I've never actually read.

Still, forty-two out of fifty-two's not bad.

If you're a purist, be warned that Kellett's goal is to amuse and he feels no compunction about making stuff up. The people he presents are based on legend, not real life, though there are factual underpinnings when he finds these funny enough. Nor is he too proud to go for low-hanging fruit: his Tolkien entry includes a joke about Tolkien's grocery list.

Interestingly, his illustrations are more true-to-life than his text. Tolkien for example holds a book (BEOWULF) in one hand and a bar glass filled with some frothy foamy drink (labelled THE EAGLE & THE CHILD) hoisted in the other. He's also smoking a pipe at the same time: clearly a multitasker.

As I said, this was a Kickstarted project. I don't know if it's available to those of us who missed the subscriber deadline, but you can find more information here:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/smallfish/anatomy-of-authors

And, on the left, you can see the ANATOMY OF AUTHORS cover (you might have to scroll down a little).

Plus if you poke around a bit on his website you'll find Kellett also offers a few posters and a pin for Gandalf Airlines, whose motto is Fly You Fools .

--John R.

*Kellett's definition of author is a generous one, including not just Tolkien and Lewis (C.S.) but Nietzsche, Seuss, Rod Serling, and two Chekovs

current weather: cold. snowing (the first big storm of the season). A good time to stay in with the cats.

current music: Helen Reddy's Greatest Hits (dug out because of the recent news of the ERA, no doubt)

current reading: another book on ancient Egypt, Kidnapping chapter of a Lindbergh biography

current audiobook: VOODOO HISTORIES by Aaronovich (a history of conspiracy theories)

Published on January 13, 2020 17:36

January 5, 2020

Tolkien biopic extras

So, I saw the Tolkien biopic (simply named TOLKIEN) at a special showing at last summer's Kalamazoo. At the time I thought it a beautiful and respectful film but found the pacing much too slow. Every scene seemed to be about twice the length it felt like it shd have been.

Accordingly, I knew I'd want a copy to re-see the movie at some later time and to have on hand for reference but was in no hurry to pick one up. Recently it occurred to me that there might be special features on the dvd that might be worth checking out --a 'making of' or 'behind the scenes' or 'The Real J. R. R. Tolkien' or the like.

I've now viewed the disk, and while there are some special features, they're sparse.

First, there's the audio commentary by the director, for those who like such things

There's also a gallery: pictures of the director directing

The sneak peaks show trailers for a strange array of movies I won't be seeing

By far the most worthwhile of all these extras are the deleted scenes (seven in all) and a First Look mini-documentary.

The mini--documentary mostly shows the lead actor and lead actress talking about the movie, with a few comments by the director thrown in. Basically these represent the idea behind the movie, what they focused on and why.

As for the deleted scenes, it's pretty clear why each was in the film and why each was taken out. Several include a single really good line (like Tolkien's calling Welsh 'the most beautiful language in the world' or Rob Gilson complaining that he's trying to keep up his art in the trenches but 'I keep running out of brown'). But the time spent on build-up wd have slowed the movie even more.

But the best thing about the movie, by far, remains its treatment of trees. It's a rare talent, but the director has managed to capture and convey Tolkien's love of trees. He even comments on this briefly in his commentary on one scene, and it shows up well in the deleted scene with Fr. Francis in a garden.

So, not essential, but not a waste of time either.

--John R.

Accordingly, I knew I'd want a copy to re-see the movie at some later time and to have on hand for reference but was in no hurry to pick one up. Recently it occurred to me that there might be special features on the dvd that might be worth checking out --a 'making of' or 'behind the scenes' or 'The Real J. R. R. Tolkien' or the like.

I've now viewed the disk, and while there are some special features, they're sparse.

First, there's the audio commentary by the director, for those who like such things

There's also a gallery: pictures of the director directing

The sneak peaks show trailers for a strange array of movies I won't be seeing

By far the most worthwhile of all these extras are the deleted scenes (seven in all) and a First Look mini-documentary.

The mini--documentary mostly shows the lead actor and lead actress talking about the movie, with a few comments by the director thrown in. Basically these represent the idea behind the movie, what they focused on and why.

As for the deleted scenes, it's pretty clear why each was in the film and why each was taken out. Several include a single really good line (like Tolkien's calling Welsh 'the most beautiful language in the world' or Rob Gilson complaining that he's trying to keep up his art in the trenches but 'I keep running out of brown'). But the time spent on build-up wd have slowed the movie even more.

But the best thing about the movie, by far, remains its treatment of trees. It's a rare talent, but the director has managed to capture and convey Tolkien's love of trees. He even comments on this briefly in his commentary on one scene, and it shows up well in the deleted scene with Fr. Francis in a garden.

So, not essential, but not a waste of time either.

--John R.

Published on January 05, 2020 22:13

Did Tolkien's Piety Affect His Scholarship?

So, in the course of his description of some of the Notes Tolkien made while working on the never-finished anthology now known as The Clarendon Chaucer, John M. Bowers records a remarkable remark regarding the following lines from the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales relating to the Monk (whose tale was one of the three Canterbury Tales included in the Gordon-Tolkien edition):

. . . a monk, whan he is recchelees,Is likned til a fissh that is waterlees,That is to seyn, a monk out of his cloystreBut thilk text heeld he nat worth an oystre.And I seyde his opinioun was good.

Bowers notes that Tolkien found fault with these lines, and ascribes it to Tolkien's faith rather than his scholarship:

As a devout Catholic, Tolkien responded to the portrait's worst anti-monasticism by rejecting a particularly unflattering passage as spurious: 'we can scarcely accept [lines 180-184], as theystand in our text, as Chaucer unadulterated.' Editors sometimesrationalize censoring their texts by claiming anything theydislike could not have been by their author. Skeat raised no doubt about the authenticity of the lines that Tolkienquestioned, nor does the current Riverside Chaucer.

(Bowers 178, emphasis mine)

Certainly Tolkien very much subscribed to the old or 'heroic' school of medieval manuscript editing, wherein modern-day scholars had great confidence that they understood Old and Middle English texts better than did the scribes who were actual speakers of those languages. And Tolkien's subsequent work on Chaucer ('Chaucer as Philologist: The Reeve's Tale') is posited on the idea that the manuscripts of Chaucer's works represent corrupt texts in need of editorial correction. What is remarkable is that Bowers ascribes Tolkien's dissatisfaction with the lines in question directly to their Xian content. So we have Tolkien's statement, without explanation, linked with Bowers' statement, again without explanation.

Reading Bowers' discussion of Tolkien's stance on editing makes me want to dig out my old essay on Tolkien as an editor of medieval texts, given at Kalamazoo a few years back but set aside when still only about two-thirds written down when other projects crowded in and interfered with its completion. Worlds enough and time.

--John R.

. . . a monk, whan he is recchelees,Is likned til a fissh that is waterlees,That is to seyn, a monk out of his cloystreBut thilk text heeld he nat worth an oystre.And I seyde his opinioun was good.

Bowers notes that Tolkien found fault with these lines, and ascribes it to Tolkien's faith rather than his scholarship:

As a devout Catholic, Tolkien responded to the portrait's worst anti-monasticism by rejecting a particularly unflattering passage as spurious: 'we can scarcely accept [lines 180-184], as theystand in our text, as Chaucer unadulterated.' Editors sometimesrationalize censoring their texts by claiming anything theydislike could not have been by their author. Skeat raised no doubt about the authenticity of the lines that Tolkienquestioned, nor does the current Riverside Chaucer.

(Bowers 178, emphasis mine)

Certainly Tolkien very much subscribed to the old or 'heroic' school of medieval manuscript editing, wherein modern-day scholars had great confidence that they understood Old and Middle English texts better than did the scribes who were actual speakers of those languages. And Tolkien's subsequent work on Chaucer ('Chaucer as Philologist: The Reeve's Tale') is posited on the idea that the manuscripts of Chaucer's works represent corrupt texts in need of editorial correction. What is remarkable is that Bowers ascribes Tolkien's dissatisfaction with the lines in question directly to their Xian content. So we have Tolkien's statement, without explanation, linked with Bowers' statement, again without explanation.

Reading Bowers' discussion of Tolkien's stance on editing makes me want to dig out my old essay on Tolkien as an editor of medieval texts, given at Kalamazoo a few years back but set aside when still only about two-thirds written down when other projects crowded in and interfered with its completion. Worlds enough and time.

--John R.

Published on January 05, 2020 09:25

January 4, 2020

Things I'd Do Differently (Dorothy Everett)

So, a few years back when I was writing my essay about Tolkien's lifelong support for women's higher education, I made no mention of Dorothy Everett, who certainly wd have been included if I'd known of her connection to Tolkien at the time.

Now, reading Bowers' book (TOLKIEN'S LOST CHAUCER), I learn that Everett was among the scholars Tolkien recommended in 1951 as a possible partner to take over and complete the stalled (since 1928) Clarendon Chaucer project.* That Tolkien was willing to turn over the project to Everett is one more piece of evidence that he took women scholars seriously, and I'm sorry I didn't include it in my piece.

So it goes.

--John R.

*looking back now I find this information was available at the time in Wayne and Christina's COMPANION & GUIDE: I simply overlooked it.

Now, reading Bowers' book (TOLKIEN'S LOST CHAUCER), I learn that Everett was among the scholars Tolkien recommended in 1951 as a possible partner to take over and complete the stalled (since 1928) Clarendon Chaucer project.* That Tolkien was willing to turn over the project to Everett is one more piece of evidence that he took women scholars seriously, and I'm sorry I didn't include it in my piece.

So it goes.

--John R.

*looking back now I find this information was available at the time in Wayne and Christina's COMPANION & GUIDE: I simply overlooked it.

Published on January 04, 2020 08:23

January 3, 2020

Tolkien's Birthday

So, today is J. R. R. Tolkien's hundred and twenty-eighth birthday.

A good time to dig out and reread a favorite from among his many works. For me, this year it's THE DRAGON'S VISIT, a little gem that exists in two versions --both good, but I much prefer the earlier variant, the one which ends

The moon shone through his green wings

the night air beating,

And he flew back over the dappled sea

to a green dragon's meeting.

--John R.

--current reading THE PENGUIN HISTORICAL ATLAS OF ANCIENT EGYPT by Bill Manley (1996)

A good time to dig out and reread a favorite from among his many works. For me, this year it's THE DRAGON'S VISIT, a little gem that exists in two versions --both good, but I much prefer the earlier variant, the one which ends

The moon shone through his green wings

the night air beating,

And he flew back over the dappled sea

to a green dragon's meeting.

--John R.

--current reading THE PENGUIN HISTORICAL ATLAS OF ANCIENT EGYPT by Bill Manley (1996)

Published on January 03, 2020 16:14

January 2, 2020

H. G. Wells' last books

So, just about the time I moved out here, over twenty years ago now, I read a compilation of two little books by H. G. Wells that between them represented his final thoughts on the fate of humanity. Having recently come across the photocopy of this I made at the time, I thought it'd make for an interesting re-reading.

Wells was a meliorist, which is to say that he believed that by working together it was possible, little by little, to make the world a better place (say, by medical research leading to vaccines or improvements in agriculture; things that improved quality of life). It was slow and hard but real progress was possible.

Writing in the last months of World War II, at a time when he was nearing eighty, suffering from cancer, and living in bomb-torn London, he decided he'd been wrong. In particular he laid a good portion of the blame on 'the necessity common minds are under to believe they have natural inferiors, of whom they are entitled to take advantage' (.11).

His response to this was twofold: one lighthearted whimsical little work and one a pessimistic prediction; the juxtaposition of their dating from about the same time makes them interesting.

THE HAPPY TURNING

In the first of these two little books he celebrates escapism through dreams: 'this delightful land of my lifelong suppressions, in which my desires and unsatisfied fancies, hopes, memories and imagination have accumulated inexhaustible treasure' (.22). Wells embraces not what Tolkien wd call the eucatastrophe of a Happy Ending but what he dubs the Happy Turning of a compensatory dream.

Wide ranged and rambling as this brief little book is, the best parts were Wells' depiction of old age as a time of falling into habits* and the two chapters in which Wells dreams of conversations with Jesus --part five: 'Jesus of Nazareth discusses his Failure' and part seven: 'Miracles, Devils and the Gadarene Swine' (particularly his take on the miracle of the loaves and fishes). The tone of these exchanges reminds me more of Blake (THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN & HELL) than Lewis (THE GREAT DIVORCE, written at about this time).

The strangest part, by far, is his chapter devoted to cursing sycamore trees. That the book is rambling, not to say weird, is one of the things that marks it as one of those books a writer writes purely for personal satisfaction.

MIND AT THE END OF ITS TETHER

Much more focused, and rather less interesting, is its companion piece, in which Wells announces that humanity, having had its chance, is now headed to extinction. A new species will replace us, which may be descended from homo sapiens or might be wholly unrelated. There's nothing we can do, Wells believes, to avoid this fate. He counsels what at first looks like a form of existentialism but is more probably stoicism: that we each meet the end with what dignity we can muster.

The two approaches, which the book's editor finds diametrically opposed, are in fact easy to reconcile if we take them in reverse order and assume that the withdrawal into dreams is one example of an individual's facing extinction (of individual and species) on his own terms.

So there it is: a great reformer turns in the end, at the end of his tether, to the cold comfort of stoicism and the warm comfort of dreams, and between them still has the wherewithall to engage in a little whimsey. It's as if Tolkien and Lovecraft collaborated on a project: the result wd no doubt be interesting but unsatisfactory.

--John R.

--current reading: Wells, THE MIND AT THE END OF ITS TETHER (#II.3549; a rereading; just finished)

*part 1: 'How I came to the Happy Turning' (.21-22). Wells' description of of his life sinking down into a repertoire of a routine of several favorite outings may strike a cord with those experiencing encroaching age or persistent ill health (I particularly liked the bit about baiting one walk with a visit to a bookstore). All in all, I thought it was the best thing in this little book, the one sign that the author of 'The Truth about Pyecroft' and similar stories had not altogether lost his touch:

In my daytime efforts to keep myself fit and active,I oblige myself to walk a mile or so on all days thatare not impossibly harsh. I walk to the right to the Zoo,or I walk across to Queen Mary's Rose Garden or down by several routes to my Savile Club, orI bait my walk with Smith's bookshop at Baker Street.

I have to sit down a bit every now and then, and thatlimits my range. I've played these ambulatory variationsnow for two years and a half, for I am too busy to goout of town, out of reach of my books . . .

I dream I am at my front door starting out for the accustomed round. I go out and suddenly realisethere is a possible turning I have overlooked!And in a trice I am walking more briskly thanI have ever walked before, up hill and down dale,in scenes of happiness such as I havenever hoped to see again . . .

Wells was a meliorist, which is to say that he believed that by working together it was possible, little by little, to make the world a better place (say, by medical research leading to vaccines or improvements in agriculture; things that improved quality of life). It was slow and hard but real progress was possible.

Writing in the last months of World War II, at a time when he was nearing eighty, suffering from cancer, and living in bomb-torn London, he decided he'd been wrong. In particular he laid a good portion of the blame on 'the necessity common minds are under to believe they have natural inferiors, of whom they are entitled to take advantage' (.11).

His response to this was twofold: one lighthearted whimsical little work and one a pessimistic prediction; the juxtaposition of their dating from about the same time makes them interesting.

THE HAPPY TURNING

In the first of these two little books he celebrates escapism through dreams: 'this delightful land of my lifelong suppressions, in which my desires and unsatisfied fancies, hopes, memories and imagination have accumulated inexhaustible treasure' (.22). Wells embraces not what Tolkien wd call the eucatastrophe of a Happy Ending but what he dubs the Happy Turning of a compensatory dream.

Wide ranged and rambling as this brief little book is, the best parts were Wells' depiction of old age as a time of falling into habits* and the two chapters in which Wells dreams of conversations with Jesus --part five: 'Jesus of Nazareth discusses his Failure' and part seven: 'Miracles, Devils and the Gadarene Swine' (particularly his take on the miracle of the loaves and fishes). The tone of these exchanges reminds me more of Blake (THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN & HELL) than Lewis (THE GREAT DIVORCE, written at about this time).

The strangest part, by far, is his chapter devoted to cursing sycamore trees. That the book is rambling, not to say weird, is one of the things that marks it as one of those books a writer writes purely for personal satisfaction.

MIND AT THE END OF ITS TETHER

Much more focused, and rather less interesting, is its companion piece, in which Wells announces that humanity, having had its chance, is now headed to extinction. A new species will replace us, which may be descended from homo sapiens or might be wholly unrelated. There's nothing we can do, Wells believes, to avoid this fate. He counsels what at first looks like a form of existentialism but is more probably stoicism: that we each meet the end with what dignity we can muster.

The two approaches, which the book's editor finds diametrically opposed, are in fact easy to reconcile if we take them in reverse order and assume that the withdrawal into dreams is one example of an individual's facing extinction (of individual and species) on his own terms.

So there it is: a great reformer turns in the end, at the end of his tether, to the cold comfort of stoicism and the warm comfort of dreams, and between them still has the wherewithall to engage in a little whimsey. It's as if Tolkien and Lovecraft collaborated on a project: the result wd no doubt be interesting but unsatisfactory.

--John R.

--current reading: Wells, THE MIND AT THE END OF ITS TETHER (#II.3549; a rereading; just finished)

*part 1: 'How I came to the Happy Turning' (.21-22). Wells' description of of his life sinking down into a repertoire of a routine of several favorite outings may strike a cord with those experiencing encroaching age or persistent ill health (I particularly liked the bit about baiting one walk with a visit to a bookstore). All in all, I thought it was the best thing in this little book, the one sign that the author of 'The Truth about Pyecroft' and similar stories had not altogether lost his touch:

In my daytime efforts to keep myself fit and active,I oblige myself to walk a mile or so on all days thatare not impossibly harsh. I walk to the right to the Zoo,or I walk across to Queen Mary's Rose Garden or down by several routes to my Savile Club, orI bait my walk with Smith's bookshop at Baker Street.

I have to sit down a bit every now and then, and thatlimits my range. I've played these ambulatory variationsnow for two years and a half, for I am too busy to goout of town, out of reach of my books . . .

I dream I am at my front door starting out for the accustomed round. I go out and suddenly realisethere is a possible turning I have overlooked!And in a trice I am walking more briskly thanI have ever walked before, up hill and down dale,in scenes of happiness such as I havenever hoped to see again . . .

Published on January 02, 2020 21:29

December 18, 2019

How Small is Too Small?

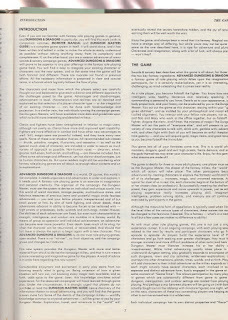

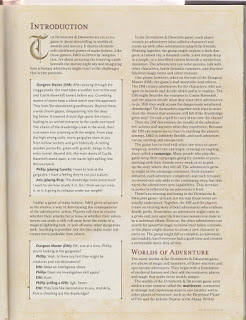

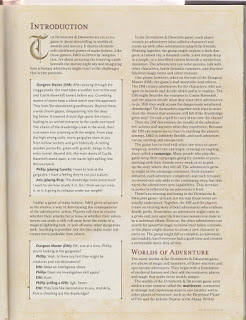

So, while in a nostalgic mood I was looking over another of my old editing jobs, the one time I edited Ed Greenwood. The project in question was the Living City compendium THE CITY OF RAVENS BLUFF (1998), the members-created home base for the RPGA, TSR's organized play AD&D setting.*

The turnover came in massively over the planned word count (not an uncommon outcome with Greenwood projects, given his ever-fertile imagination). I consulted with my boss, and rather than cutting the text by 40% we decided to keep all Greenwood's and the fan-generated text.

We made it all fit by reducing the font size to 7-point type.

For 1700 words per page.

For 160 pages.

My memory of the next month is of long hours spent at my keyboard down at the office, both during the weekdays and during all the weekends too until the project was done.

It wd be nice to be able to say that I got extra time to work on this one, given the amount of extra material I had to work on, but alas that was not the case.

Still, folks seemed to like it, which is the important part. And fans of the Living City who bought it certainly got their money's worth.

--John R.

P.S.

For the sake of comparison, here's a page from the 1st edition PLAYER'S HANDBOOK, which now looks really small to my aging eyes. This is followed by a page from the current PH, which while smallish is much more readable. Lastly comes a page from THE CITY OF RAVENS BLUFF, just to show how small 7-point type is.

*One of the seven projects I edited that first year at WotC --ironically while waiting to begin work editing a project that never came to fruition: the DOMINARIA setting for AD&D. The team members for that one were Lisa Stevens, Jonathan Tweet, Jesper Myrfors, and myself, shortly thereafter joined by Chris Pramas

The turnover came in massively over the planned word count (not an uncommon outcome with Greenwood projects, given his ever-fertile imagination). I consulted with my boss, and rather than cutting the text by 40% we decided to keep all Greenwood's and the fan-generated text.

We made it all fit by reducing the font size to 7-point type.

For 1700 words per page.

For 160 pages.

My memory of the next month is of long hours spent at my keyboard down at the office, both during the weekdays and during all the weekends too until the project was done.

It wd be nice to be able to say that I got extra time to work on this one, given the amount of extra material I had to work on, but alas that was not the case.

Still, folks seemed to like it, which is the important part. And fans of the Living City who bought it certainly got their money's worth.

--John R.

P.S.

For the sake of comparison, here's a page from the 1st edition PLAYER'S HANDBOOK, which now looks really small to my aging eyes. This is followed by a page from the current PH, which while smallish is much more readable. Lastly comes a page from THE CITY OF RAVENS BLUFF, just to show how small 7-point type is.

*One of the seven projects I edited that first year at WotC --ironically while waiting to begin work editing a project that never came to fruition: the DOMINARIA setting for AD&D. The team members for that one were Lisa Stevens, Jonathan Tweet, Jesper Myrfors, and myself, shortly thereafter joined by Chris Pramas

Published on December 18, 2019 20:53

December 15, 2019

Dunsany on the Pharaoh's Boat

So, amid the many pieces, good and bad, about Egypt I've been watching in recent weeks were some about Pharaoh Khufu's boat, found buried alongside The Great Pyramid. This reminded me of Dunsany's story about the pharaoh's boat. I'd read this years ago but not realized back then how large and impressive the ship was. For those who like both Egyptology and fantasy literature, the story can be found in THE FOURTH BOOK OF JORKENS (Arkham House 1948), pages 101-103.* For those without access to the original volume, here's a slightly abridged version of the story:

'By Command of Pharaoh'The Fourth Book of Jorkens (Arkham House, 1948) p. 101-103

. . . I was doing a bit of archeology, digging near the Great Pyramid, a most fascinating occupation . . .

I don't know much about archeology, but my friend Ali Bey knew everything, and I asked him to come and dig with me for a few weeks, and we put up a couple of tents and employed a few workmen, and set out to look for that past . . . [H]e smiled when I said we would dig for a few weeks . . . He tried to get me to see that it would be a matter of months: and so it would have been . . .

[W]e had not been digging long when we came to rock, natural rock, but going down with such a queer curve on it that we soon thought it was not as natural as it seemed; and in a few days we came on a boat. The rock was nothing else than a sepulchre, hollowed out to bury a boat in, a fine boat too, some twenty yards long. Well, of course we sent it to the museum, and some oars we found with it. And that night Pharaoh appeared to me in a dream.

He came into my tent in the moonlight, from the direction of the Great Pyramid, and asked what I'd done with his boat. Well, I said that I didn't think a man wanted a boat in a desert, and that I'd sent it away. And he said How did I suppose a king could row across the sky with the stars if he hadn't got a boat? That, of course, is a difficult question to answer, and I didn't do it very well; and I could see he thought me the damnedest idiot that ever had been. I tried a few lame excuses, but made no headway, and he was only getting angrier.

You see it wasn't any use to suggest an aeroplane, because Pharaoh would never have heard of one, and to try to make him see that a king needn't row across the sky was entirely impossible; one saw that at once: he merely thought me a hopeless idiot for having such an idea. Indeed my point of view seemed so idiotic to him that he was almost inclined to spare me, and stood there thinking, all dim in the moonlight but then he decided that not even my ignorance was any excuse for taking his boat away from a king, and said briefly that the penalty must be death. Well, that, though it didn't wake me up, stimulated my wits a good deal, and I said, 'Look here, you can't do that.'

'Why not?' asked Pharaoh, immensely astonished.

'You haven't the power,' I said. Which seemed pretty obvious, as he was not appreciably thicker than a shadow.

'I have great power in dreams,' said Pharaoh.

And the sound of the word made me realize at that moment that it was only a dream, and that I must wake at once. It took a huge effort of will. I realized that, if I stayed asleep any longer, I should be in Pharaoh's power. I could hardly do it, though I knew my life was at stake. It was a sheer effort of will. Well, I woke up and Pharaoh vanished, and I reached for my shot-gun. I always keep a 12-bore shot-gun beside my bed, in deserts and such places, because you never know when it may come in handy. Not loaded, of course, because a loaded shot-gun beside your bed may be more dangerous than anything else, but I kept the cartridges handy, and now I slipped two of them in, and just in time.

'But,' said Terbut . . . 'I thought you said it was only a dream.'

Certainly, said Jorkens. But don't you see that, if Pharaoh could send a dream like that to me, and a very vivid and detailed dream, he could just as easily sent it to my friend Ali Bey, whose tent was only thirty yards away. And that was the very thing that Pharaoh did. I expect he communicated easier with Ali Bey than he did with me, because Ali, like several Egyptians that I have known, had a quite unmistakable likeness to some of the busts of scribes and priests and officers of some of the earlier dynasties that used to reign near that pyramid; so that he was almost certainly descended from men who had long ago formed the habit of taking orders from Pharaoh. This naturally made it easier for Pharaoh to get in touch with them quickly.

Anyway, he did; because I heard bare feet near my tent, which I would never have heard if I had not been listening for them, and there was Ali Bey outside with a long knife in his hand, standing quite still. What made him stand still must have been the click of my gun closing, which to a sportsman and first-rate shot like Ali Bey must have been quite unmistakable.

The error I think Pharaoh made was one of the greatest errors a ruler can make: he was too detailed, instead of leaving trifles to his subordinates. What he probably did was to inspire Ali Bey to take a sharp knife in his right hand, and so on and so on . . . Of course he knew nothing of fire-arms; but if he had left the details to Ali Bey, who, as I said, was an excellent shot, instead of commanding him to come with a knife, there would have been no difficulty in shooting me through the side of the tent in the moonlight.

Well, Ali Bey walked quietly back to his tent after one or two words to me appreciative of the moon, and gave me no more trouble that night; and I left before dawn.

I often write to Ali Bey, and get charming letters in answer, and letters of a very high scientific value. I bought a canoe at the Army and Navy Stores and sent it out for Pharaoh, to be put in the hollowed rock; and Ali saw to that. But I never quite knew if it would satisfy the old king: you see, he had been accustomed to a boat twenty yards long; and, even if the canoe suited him, one never knew if his priests wouldn't say that it was the wrong make. No, I never went back to Egypt. I think the country is rather too full of dreams.

And for a glimpse of what one of the original excavated boats looks like, here's one of the myriad short video pieces on the topic. Since Dunsay's story was published before the discovery of the particular boat shown here (the fifth I think), he must have been drawing on one of the previous discoveries.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5pCN7peywDw

--John R.

*Taking my copy of this book down from the shelves for the purposes of this post, I was surprised to see that it's autographed "Best wishes -- August Derleth -- 7/27/68". According to my annotation I got this book on Saturday April 19th 1997 as a gift from my friend the late Jim Pietruez. So thanks Jim for the good deed, still much appreciated after all these years.

Published on December 15, 2019 22:32

December 12, 2019

Tolkien and Gibbon's DECLINE AND FALL

So, a few years ago I posted on some online forum* a query about whether Tolkien ever read Edward Gibbon's famous THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE. On the one hand, it is a standard work on a subject of perennial fascination, widely read and hugely influential. On the other hand, this work was on The Index, the list of books Catholics are forbidden to read without special permission. The list was abandoned but not abolished in the 1960s, but it was in force for most of Tolkien's lifetime.

Oronzo Cilli, in TOLKIEN'S LIBRARY, assumes Tolkien owned or at least consulted a copy of this book on Shippey's authority (Cilli 95-96). Shippey makes a good case for Tolkien's first-hand knowledge of Gibbons largely through inherent probability (Shippey's Road 1992 edition p. 301). Now thanks to John Bowers' new TOLKIEN'S LOST CHAUCER, we have direct proof. Bowers reproduces a manuscript page that is part of the draft for JRRT's commentary on Chaucer's translation of Boethius (Bowers page 144) in which Tolkien cites Gibbon, directing the reader to a specific chapter of DECLINE AND FALL. Based upon this, Bowers concludes "Tolkien knew Gibbon from his own reading" and also believes that JRRT "shared the historian's sense of decline when writing about the 'long defeat' in Middle-earth." (Bowers 147).

So, that seems to settle things. It's nice to have proof of what we already believed.

Of larger significance, this new evidence that Tolkien read at least one work on the Index has interesting implications of its own.

--John R.

--current viewing: House Judiciary Committee Hearings (in part)

--current music: "Why Don't You Love Me Like You Used to Do?" by Hank Williams (stuck in my head the last three days)

*I'm no longer sure which. Perhaps the Mythsoc list. At any rate, it seems not to have been on my blog, where I usually post such things, and so may have pre-dated the blog's commencement.--JDR

Oronzo Cilli, in TOLKIEN'S LIBRARY, assumes Tolkien owned or at least consulted a copy of this book on Shippey's authority (Cilli 95-96). Shippey makes a good case for Tolkien's first-hand knowledge of Gibbons largely through inherent probability (Shippey's Road 1992 edition p. 301). Now thanks to John Bowers' new TOLKIEN'S LOST CHAUCER, we have direct proof. Bowers reproduces a manuscript page that is part of the draft for JRRT's commentary on Chaucer's translation of Boethius (Bowers page 144) in which Tolkien cites Gibbon, directing the reader to a specific chapter of DECLINE AND FALL. Based upon this, Bowers concludes "Tolkien knew Gibbon from his own reading" and also believes that JRRT "shared the historian's sense of decline when writing about the 'long defeat' in Middle-earth." (Bowers 147).

So, that seems to settle things. It's nice to have proof of what we already believed.

Of larger significance, this new evidence that Tolkien read at least one work on the Index has interesting implications of its own.

--John R.

--current viewing: House Judiciary Committee Hearings (in part)

--current music: "Why Don't You Love Me Like You Used to Do?" by Hank Williams (stuck in my head the last three days)

*I'm no longer sure which. Perhaps the Mythsoc list. At any rate, it seems not to have been on my blog, where I usually post such things, and so may have pre-dated the blog's commencement.--JDR

Published on December 12, 2019 22:35

John D. Rateliff's Blog

- John D. Rateliff's profile

- 38 followers

John D. Rateliff isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.