Andrew Collins's Blog, page 30

October 19, 2012

The horror

Behold, the Collins family kids, in a row, holding their favourite present on Christmas Day, 1975. From left to right: Andrew, aged 10, holding Denis Gifford’s Pictorial History of Horror Movies, a large hardback book whose wraparound glossy dust jacket has long gone, but whose vivid painterly back-cover collage of images is captured in all its glory; Melissa, aged 5, wearing her nurse’s uniform; and Simon, aged 8, who seems already to have constructed an anti-tank gun from a khaki Meccano set. We didn’t want for much.

The reason I’m printing this seemingly random happy snap from the long-ago past is that I met and interviewed the extraordinary Mark Gatiss for Radio Times this week. It all happened very fast: BBC4 offered him up for interview on Monday, to promote Horror Europa, his personal, 90-minute documentary about European horror cinema – showing on the night before Halloween, and a direct follow-up to his well-received A History of Horror from 2010 – I arranged to meet him on Tuesday, over pasta during an hour’s break from “tech rehearsals” at the Hampstead Theatre for 55 Days by Howard Brenton, in which he plays Charles I to Douglas Henshall’s Oliver Cromwell (and which opened for previews on Thursday); I transcribed and wrote it up at 900 words on Wednesday; and the two-page layout was signed off yesterday.

The above still is from A History of Horror, when Mark was bearded. Although he is bearded as King Charles, it is a stick-on beard, and he was clean shaven over dinner. This was a labour of love for me – I jumped at the chance, even though I’m way too busy to write 900 words – which is apt, as these documentaries are a labour of love for him. He’s 46 – in fact, he turned 46 on Wednesday, so he was 45 when I dined with him – and we share the same boyhood obsession with horror movies, something that informed our discussion over calamari and chips (me) and salmon and spaghetti (he). In A History, he explicitly revealed how important the Gifford book was to him, and whether he likes it or not, I bonded with him forever.

I loved this book. To say it was my Bible sounds sacrilegious, but then, it was filled with evil and supernatural images. First published by Hamlyn in 1973, it was still a relatively new book when I got it for Christmas in 1975, and I’d had it in my sights for ages, thumbing through it in WHSmith’s in the Grosvenor Centre of a Saturday morning shopping trip. Its unofficial companion in my house – and, it transpires, in the Gatiss house in Country Durham – was Alan G Frank’s Horror Movies, published in hardback by Octopus in 1974 under the Movie Treasury imprint and subtitled Tales of Terror in the Cinema. (I had to wait until Christmas 1978 to own this.)

A copy, in its original dust jacket, appears on top of a prop telly in Horror Europa. Another touchstone. Of course, it would be easy to be jealous of Mark Gatiss, who gets to turn his childhood horror nerd obsession into television programmes – to exorcise it, if you like – but these programmes are so good, he fronts them with such urbane charm and enthusiasm, and he’s so true to his roots, we should all be grateful that he’s seemingly in charge of horror at the BBC.

There’s something glorious about finding common ground with people of your own age. You may remember that I was able to find an instant bond with JJ Abrams when I interviewed him about his film Super 8 last year. He, too, is 46. It’s no surprise to discover that he was a fanboy, as we weren’t called in the 1970s, but I was still over the moon to see the film’s chief protagonist Joe carefully painting an Aurora glow-in-the-dark model of the Hunchback of Notre Dame in an establishing scene (the film is set in 1979). Here’s my grab:

I was so mad about these kit models. I think I had them all, at various stages – the Hunchback, Phantom of the Opera, Godzilla, King Kong, the Wolfman, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the Salem Witch, Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, Dr Jekyll, the Mummy, the Forgotten Prisoner of Castel-Mare – as my Airfix-inclined friends and I would swap the finished items, and usually repaint them in new Humbrol colours to claim them as our own. At this age – and I got my first, the Hunchback, and my second, Dr Jekyll, for my ninth birthday in 1974 – I was utterly preoccupied with horror, especially the iconic monsters that Universal defined itself with in the 1930s, not that I really had any concept of the 1930s at that wide-eyed age.

I was so mad about these kit models. I think I had them all, at various stages – the Hunchback, Phantom of the Opera, Godzilla, King Kong, the Wolfman, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the Salem Witch, Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, Dr Jekyll, the Mummy, the Forgotten Prisoner of Castel-Mare – as my Airfix-inclined friends and I would swap the finished items, and usually repaint them in new Humbrol colours to claim them as our own. At this age – and I got my first, the Hunchback, and my second, Dr Jekyll, for my ninth birthday in 1974 – I was utterly preoccupied with horror, especially the iconic monsters that Universal defined itself with in the 1930s, not that I really had any concept of the 1930s at that wide-eyed age.

Ironically, when The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the 1939 classic starring Charles Laughton, was on television in June 1974, Simon and I were too scared to watch it! When BBC2 starting running their double-bills on a Saturday night around that time, we dared each other to watch what would be ultra-tame, fag-end stuff like House of Frankenstein, and The Mummy’s Ghost on the black-and-white portable, after dark. We weren’t the first boys to find something thrilling in being scared out of our wits, and I’m glad we had no prejudice about whether a horror film was old or new, cool or uncool, black-and-white or colour.

One of the many things Mark Gatiss and I agreed upon on Tuesday was that it was the very unattainability and the mystery of the stills in our horror books that made them so alluring. What would The Student Of Prague or The Golem or The Cabinet of Dr Caligari actually be like to watch, moving about? I choose three silents because neither did we have any prejudice about silent movies at that age. How innocent and free from preconception we were!

So, this has been a hymn to childhood, or at least childhood in the pre-video age, when horror nerds had access to almost nothing but stills in books, plastic models and our imaginations to fire up our enthusiasm.

Horror Europa is on BBC4 on Tuesday 30 October at 9pm. My interview with Mark appears in next week’s Radio Times, out on Tuesday. And while we’re plugging, to go all BBC announcer for a moment, Mark Gatiss is currently appearing in 55 Days at the Hampstead Theatre … (nobody has asked me to do that link, which is why I’m happy doing it)

PS: My sister didn’t become a nurse; my brother did join the Army; I took my Pictorial History of Horror book to an Italian restaurant in Swiss Cottage when I was 47 to show it to a man, who whooped, “the green one!”

October 18, 2012

C.R.E.E.P.S.H.O.W.

I mention this only as a matter of record. In November 1973, when I was eight years old, our Friday afternoon art project at Abington Vale Primary School was to make a papier-mâché puppet. If I remember correctly, we moulded the head around a balloon with strips of newspapers and glue, let it harden, painted it, decorated it, then added the hand-puppet body using rudimentary dressmaking skills, which actually seem fairly sophisticated for an eight-year-old boy, especially the padded hands, although I suspect we had assistance in this.

This brief was fairly typical of the modern, co-educational thrust of comprehensive education in the early 70s: boys and girls mucking in and blurring the distinctions between gender-specific crafts and activities.

As noted in my 1973 diary on Friday November 16, “Today it was art and we are making puppets out of papier-mâché. I am making Jimmy Savile but I haven’t put his hair on yet!”

Thanks to my own adult predisposition to archiving (otherwise known as “hoarding”), I can present physical evidence of the completed Jimmy Savile puppet, with the trademark hair, fashioned from string. The key creative decision, aged eight, to make Jimmy Savile “evil” was, I have to admit, less a prescient appreciation of the darker side of the nation’s favourite kids’ TV host (as previously stated, we loved Jim’ll Fix It in our house), more a reflection of a general boyhood obsession with horror films, as filtered through Monster Fun comic, Aurora glow-in-the-dark kit models, Bobby “Boris” Pickett’s Monster Mash (a reissue of which 1962 novelty tune was a hit that October) and Denis Gifford’s Pictorial History of Horror Movies. I equated blood running out of nose and eye as “evil.”

Who knew? (That is the question.)

October 16, 2012

See you this Tuesday

This is confusing. The most recent Telly Addict went live on Friday afternoon. And here’s a new one? Already? Yes, the people upstairs at the Guardian have decided to spread out their video content across the week, so that it doesn’t bottleneck at the weekends. We negotiated Monday as a new write-and-record date, with a view to “publishing” on a Tuesday morning at around 10am. This will hopefully give us a better chance of being picked up and, even better, viewed. (User numbers predictably drop off at weekends.) Due to the “short week” (ie. the weekend), I have reviewed four comedies that are currently on – and the exquisite Hunderby on Sky Altantic, which has just finished – so, eyes down for the multi-award-winning Fresh Meat, which has returned for its second series to C4; Modern Family, whose fourth season has just started on Sky1; and Nurse Jackie, whose fourth season has just started on Sky Atlantic. If you are a Sky refusenik, then just enjoy the clips of some of the best comedy on telly at the moment, in my opinion. And put Tuesday in your diary. (The Great British Bake Off final will be reviewed then, safely after the event, so that I can actually name the winner and not enrage spoiler-alert whiners!)

This is confusing. The most recent Telly Addict went live on Friday afternoon. And here’s a new one? Already? Yes, the people upstairs at the Guardian have decided to spread out their video content across the week, so that it doesn’t bottleneck at the weekends. We negotiated Monday as a new write-and-record date, with a view to “publishing” on a Tuesday morning at around 10am. This will hopefully give us a better chance of being picked up and, even better, viewed. (User numbers predictably drop off at weekends.) Due to the “short week” (ie. the weekend), I have reviewed four comedies that are currently on – and the exquisite Hunderby on Sky Altantic, which has just finished – so, eyes down for the multi-award-winning Fresh Meat, which has returned for its second series to C4; Modern Family, whose fourth season has just started on Sky1; and Nurse Jackie, whose fourth season has just started on Sky Atlantic. If you are a Sky refusenik, then just enjoy the clips of some of the best comedy on telly at the moment, in my opinion. And put Tuesday in your diary. (The Great British Bake Off final will be reviewed then, safely after the event, so that I can actually name the winner and not enrage spoiler-alert whiners!)

October 15, 2012

The 834mph question

These are the facts. I offer no editorial on them at this stage. Yesterday, on Sunday October 14, the Austrian man Felix Baumgartner, a former paratrooper, jumped out of a balloon that was 23 miles above the earth, and, ten minutes later – four minutes and 19 seconds of those in freefall – landed on the earth – specifically, Roswell, New Mexico – having reached a speed of 834mph along the way, breaking three world records, including becoming the world’s first “supersonic skydiver” by breaking the sound barrier at Mach 1.24.

His jump was sponsored by the Austrian, ox-bile-based energy drink Red Bull, but its scientific impetus was NASA’s desire to create better pressurised survival suits for astronauts who might fall out of the stratosphere. (The one that kept Baumgartner’s body intact against the hugely varying pressures that marked his drop back to earth, prevented his blood boiling and his lungs exploding.)

A categorically brave man, Baumgartner has parachuted off buildings and mountains. He prepared for this record attempt by performing two practise freefalls, one from 71,000 feet in March and another from 97,000 feet in July. But this one was more like 128,000 feet, or 39km, if you prefer it in new money.

So, as I understand it, he’s now the first human to ever break the sound barrier in freefall; that was the highest freefall altitude jump and the highest manned balloon flight. I wish Roy Castle had been around to see it. Like most people, I saw the footage from which the iconic grab above is taken, and gasped as Baumgartner stepped out of the capsule and into … space. It was amazing. I was amazed that anyone would wish to do that, and that anyone could do that, and not retreat, bawling and sucking their thumb, into the capsule until somebody came and got them. Part of me thinks he is a nutcase. But I guess we need nutcases sometimes.

I do not follow television on Twitter, but had a little look afterwards and it was predictably awash with exclamations. (As we found during the Olympics, Twitter is the perfect medium for exclamations, and it can be quite sweet to see normally erudite people simply gasping in 140 characters.) I threw this question into the mix, partly out of mischief, but partly out of genuine inquiry. Making statements, or pronouncements, can sometimes seem a little arrogant; I quite like asking things instead. I Tweeted:

A man jumped 23 miles out of a balloon. And we have learned … what?

I was, within seconds, bombarded with responses. Most of them took my question literally and answered it. Some of them made jokes. I found this stimulating. Because it’s almost unarguably an amazing feat, and an amazing thing to have seen, I wasn’t actually looking for a fight. There’s little room for philosophical manoeuvre here: it’s amazing. But it’s a valid supplementary question: what have we learned from it?

The actual answer is that a man can do it. And that a man-made pressurised suit can withstand it. This is the research. More elliptically, we have learned that Red Bull has a phenomenal marketing department. We have also learned that the Space Race isn’t over, contrary to the Billy Bragg song The Space Race Is Over. I get the Space Race. It was all about global posturing during the Cold War, a show of military strength by the world’s two superpowers after the Second World War. In this brave new world, a super-sized democracy and a totalitarian state could afford to spend whatever it took to get a man on the moon, and get him there first (after a couple of dogs and monkeys). I also know that many technological advances were made during the Space Race that impacted on our earthbound lives, albeit mostly in kitchenware, dried fruit and sports gear, and, to be fair, satellites.

But you might ask the question, why are we still exploring space when there’s so much that’s going wrong with the planet we already own? Endeavour and exploration for endeavour and exploration’s sake is one thing, but it’s not as if we have finished with Earth, and it costs a lot of money to keep sending things up there. (Even, one assumes, the relatively austere sending up of a balloon to 128,000 feet and having a man jump out of it.)

There’s a Jerry Seinfeld routine, which I wish I could quote, in which he wryly suggests that the minute you have to invent a crash helmet to protect your skull while riding a motorcycle, you have to wonder why you invented something that could smash your skull in the first place. I go along with this. If we didn’t send people into space, we wouldn’t need to invent a pressurised protection suit for them to wear. We could spend the money on something that would help people on earth. No?

I realise that by even asking an innocent question about what we have learned from the amazing feat of Felix Baumgartner I risk upsetting the applecart of blanket adulation for him. I do not wish to subtract from his achievement, and his insane bravery. If you are not in awe of him, then you must think yourself as brave, or more brave. I am so much less brave than him, it would be weird to not be in awe of him. But surely we are allowed to question the point of the feat.

One person replied to my Tweet (“and we have learned … what?”): “That some people aren’t impressed by anything?” He was implying that I was not impressed by the skydive. But I was. I am impressed by big things, high things, tall things, far-away things, deep things … but impressing me isn’t enough. (Actually, I’m more impressed by selfless acts of charity or compassion than self-indulgent acts of bravery or endurance, but that’s just me.)

Another wit responded: “Man has opinions on music and films and telly. And we have learned … what?” Ouch. That’s me told. I’m not permitted a question, because I don’t do scientific feats.

Another asked, “Did we need to learn anything from it? It was a fantastic feat, just appreciate that.” Again, I’m being told to appreciate something. I do find a consensus issue like this one – and the Olympics, actually, although we’ve done those – slightly bullying. There’s only one verified reaction, and if you stray from that orthodoxy you are some kind of spoilsport.

And another: “That there’s pretty much nothing in this world that someone somewhere won’t be sniffy about?” And another: “If you are going to reduce everything to those sort of terms then almost all human endeavour is pointless.” Hmm, maybe he’s right. At least he didn’t say what so many people did, especially in the Guardian comments section under the story: “He’s got balls of steel.” Yep, because having balls is better than not having them, and having ones made of metal is better than having ones made of flesh. Are we still equating testicles with superiority? I do wonder often why women, on the whole, don’t tend to do things like jump out of things and climb up things and do things really fast just for its own sake. Why is that? (Women are great, aren’t they? I think so.)

It does not do to dwell 24 hours a day on poverty, injustice, corporate greed and cruelty to animals and people – like I do – you risk your brow becoming permanently furrowed, which is not a good look. But these issues require more immediate attention than space suits. So may I respectfully recommend that we look down with as much wonder as when we look up? And if someone questions something, do not ostracise them for doing so.

As Marge Simpson once said, “There’s no shame in being a pariah.”

October 14, 2012

Left to right

Two European films seen a few days apart, one French, one German, and how different. Untouchable, the one everybody’s heard of, is a feelgood French comedy and box office smasheroo with little time for thematic subtlety or narrative ellipse, the sort to break out of the arthouse ghetto and find an audience who wouldn’t normally touch subtitles with a bargepole; Barbara, less concerned with the quest for bums on seats but nonetheless honoured by the festival circuit and laurelled at Berlin, is a more demanding watch, although drew an impressive crowd at the Renoir two nights ago, and paid back in different ways.

I’m sure you’re abreast of Untouchable (or, to use the French, Intouchable): a quadriplegic rich man rediscovers his lust for life thanks to a Senegalese carer from the projects who refuses to stand on ceremony and speaks the truth while all around him tread carefully. Both parts are played with great spirit: François Cluzet – best known here for Tell No One (or Ne le dis à personne) – and Omar Sy – most recently seen in the irksome Micmacs – bring humanity to the frankly cut-out characters they have been given. Cluzet plays paralysed from the neck down with consummate dedication, and, in doing all the work with his face, proves his chops in a way that only playing the disabled can. Sy is the livewire, and certainly feels like he is riffing on the script, whether he is or not, and that’s terrific. It will make you feel good, in that it depicts hope out of hopelessness, and makes the optimistic prediction that upper-class French people can learn to rub along with African immigrants. It also knows how to push buttons.

Some might say that Driss, the character Sy plays, is a reductive stereotype, in that he’s poor, he’s initially workshy and, hey, he’s a great dancer. He also conforms to the “Magical Negro” achetype so beloved of Hollywood (an inevitable English-language Weinstein remake is already on the cards, in which the “Negro” may become even more “magical”). All that considered, Driss is the beating heart of the film – and it’s he who won last year’s Cesar for best actor, beating The Artist‘s Jean Dujardin. It could be argued that we should applaud the film for foregrounding an African character, and performer. He is employed to be the “arms and legs” of Cluzet’s depressed widowed millionaire in his big, lifeless mansion, and does this job with athletic aplomb, at one point cutting a rug to Earth, Wind & Fire in a showcase scene for his talents. But even here, I couldn’t help but think: really? All the white people who work in the mansion are, of course, rubbish dancers. Again: really?

This isn’t a spoiler, but at the very end, the filmmakers show home-movie footage of the real-life quadriplegic and his carer, Philippe Pozzo di Borgo and Abdel Sellou, who had previously been featured in a documentary (Sellou has also written a bestselling memoir You Changed My Life). Notice anything about the carer’s name? Yes, it’s Algerian. Not Senegalese. If you look him up online, he’s nothing like as black as Omar Sy. So why did the filmmakers change his nationality from North African to West African? Did they require Driss to look more black, more African, to help make their ebony-and-ivory point for the broadest audience possible?

Because Untouchable makes fairly blunt and sweeping – literally, black and white – drama from the thorny subject of racial difference and racial prejudice, and it’s based on a true story, I can’t help wondering why the race of a key character has been changed? I’m genuinely interested to know, particularly as we’re in a country like France, where race is a burning issue. Maybe it was simply so that they could cast the likeable Sy?

If you can shed any light on it, let me know. And I’d be interested to know how “good” it made you “feel”. I felt good about the performances, but less so about the film, which, despite its apparent roots in veracity, seemed more like a fairytale than anything else.

Barbara is being sold with this quote from, it says, MSN: “Anyone who loved The Lives Of Others should see this.” (I’ve searched MSN’s film reviews and can find no context for this quote, incidently.) Hey, you can’t blame them; The Lives Of Others is a German-language film that successfully crossed over, internationally, and won the Best Foreign Language Oscar, so if selling this is all about reassuring the potential audience, job done, I guess. And both films are set in the early 80s in East Germany, and show invasive, paranoid surveillance by the Stasi. The big difference between the first film and this one, is that it was a thriller, and this isn’t, despite initial appearances.

Directed by Christian Petzold, of the Berlin School – whose previous film, Yella, had a wider release than his previous work – it stars his muse, Nina Hoss as the titular doctor who is exiled from East Berlin to a small rural town on the Baltic coast after incarceration for some unmentioned crime against the state. (I’ve since read that it was simply to express a wish to leave the GDR, although I didn’t pick this us from the film, which does anything but spoon-feed, to its credit.)

She is understandably wary of those around her, assuming she’s being watched – which she is – and acting accordingly. She is an intelligent woman, and an excellent doctor, but she keeps herself to herself, constantly putting distance between herself and her seemingly benign boss, the bear-like Ronald Zehrfeld, who fancies her. Barbara moves at a slow, exacting pace, and gives little away at first, which actually reflects the general paranoia of the time and place. Even out in the country, people are wary of who’s listening. (Barbara’s nemesis is very real, Rainer Bock’s seemingly sadistic Stasi officer, so it’s not as if it’s all in her mind.) Like the decor of the run-down buildings – the hospital, her apartment with the fizzing wall socket and un-tuned piano – this is a spare, minimalist film, but against such an austere background, symbolic movement – the freedom of a bicycle ride, the coastal winds buffeting the trees – feel more significant.

I don’t know Petzold’s sork, and have not seen Yella, but I’ve a huge soft spot for the New German Cinema of the 60s and 70s, and the more recent revival of Germany’s output – including the obvious breakout likes of The Lives Of Others and Downfall – and this slots comfortably into that intellectual/historical renaissance. Many of the 70s films looked back at the war and Nazism, while the post-unification films use the fall of the Berlin Wall as their focal point.

I recommend Barbara. It works harder for its audience than Untouchable, and we must work harder for it. But there’s nothing wrong with hard work.

October 12, 2012

“H” bomb

Without any attempt at forcing the issue, Sesame Street or QI style, this week’s Telly Addict is brought to you by the letter “H”. Three dramas, each beginning with the same letter, and two of them beginning with the word “Home.” First, the return of Homeland to C4 for its make-or-break second season; second, a new one to ITV1, Homefront (which isn’t one word, but we’ll let it off as I liked it); and finally, Hunted on BBC1, the big-budget Transatlantic co-production that we previewed at the Edinburgh Television Festival. Oh, and a quick morsel of Bake Off, because it would be rude not to.

Without any attempt at forcing the issue, Sesame Street or QI style, this week’s Telly Addict is brought to you by the letter “H”. Three dramas, each beginning with the same letter, and two of them beginning with the word “Home.” First, the return of Homeland to C4 for its make-or-break second season; second, a new one to ITV1, Homefront (which isn’t one word, but we’ll let it off as I liked it); and finally, Hunted on BBC1, the big-budget Transatlantic co-production that we previewed at the Edinburgh Television Festival. Oh, and a quick morsel of Bake Off, because it would be rude not to.

October 5, 2012

Two feet in the past

There is a period drama theme to this week’s Telly Addict. Not my doing, really, but the overworked drama departments, whose current obsession with the past might well be due to a commissioner-led preference for the “theme park with safe rides” option, as persuasively discussed by Mark Lawson in, oh yes, the Guardian the other week. We catch up with BBC4′s Room At The Top (delayed by a mere 18 months due to rights issues); BBC1′s The Paradise; and Sky Atlantic’s Boardwalk Empire, back for its third season and as vital as ever. (Unless you don’t have Sky, in which case, it will be back for its third box set in the New Year.) Also, back in the real world, nods to Doctor Who and The Great British Bake Off, specifically, Cathryn and her old-fashioned, family-friendly exclamations while under teacake pressure.

There is a period drama theme to this week’s Telly Addict. Not my doing, really, but the overworked drama departments, whose current obsession with the past might well be due to a commissioner-led preference for the “theme park with safe rides” option, as persuasively discussed by Mark Lawson in, oh yes, the Guardian the other week. We catch up with BBC4′s Room At The Top (delayed by a mere 18 months due to rights issues); BBC1′s The Paradise; and Sky Atlantic’s Boardwalk Empire, back for its third season and as vital as ever. (Unless you don’t have Sky, in which case, it will be back for its third box set in the New Year.) Also, back in the real world, nods to Doctor Who and The Great British Bake Off, specifically, Cathryn and her old-fashioned, family-friendly exclamations while under teacake pressure.

Dear Jim

Diary entry: Saturday, 1 January, 1977

Made a Lego house in the morning. Watched Swap Shop. Watched Willy Wonka And The Chocolate Factory in the afternoon, after playing Monopoly. New series of Jim’ll Fix It and Dr Who. Watched Starsky And Hutch.

Jimmy Savile, or Sir Jimmy Savile as he officially remains for now, died less than a year ago, on October 29, 2011, two days before his 85th birthday. His body lay in state, in a gold coffin, at the Queens Hotel in Leeds, and 4,000 people lined up to pay their respects. When he died, his secrets died with him. Or at least, they did in theory. Unfortunately, since his death, a number of people have come forward to say that they were abused by him when they were children. Since ITV’s Exposure documentary aired on Wednesday, more have lined up to join them and add to the cacophony of complaint against his good name. I’m not a detective, but when such a broad catalogue of independent testimony corroborates itself in this way, it’s hard not to find the evidence compelling.

The disturbing picture emerging is of a depraved sexual predator with a penchant for girls of around 15 who used his power as a national treasure, a figure on the pop scene, and the host of television shows aimed at children to get what he wanted. By all accounts, he pulled the egregious trick of frightening his victims into keeping quiet, and filling them with shame for something he had perpetrated. By preying on troubled girls from an approved school in Surrey, he exploited a bond of trust between himself and the institution, in much the same way that paedophile Catholic priests use the sanctity of the church to have their way with altar boys.

I only ever sent one letter to Jim’ll Fix It. It was in 1976. I asked Jim – or “Jim’ll” as we jokily called him – to fix it for me to meet my hero, the Daily Express cartoonist Giles, so I could show him my own cartoons. (As related in my book, I even drew some Giles characters on my letter and used coloured pens on the envelope – as if no Jim wannabe had ever thought of that before.) It was all for nothing; I never got a sniff. But then neither did my brother Simon and he’d asked “Jim’ll” to fix it for him to visit the Action Man factory, which ought to have been right up the programme’s street with their appetite for subliminal advertising.

In later, more self-conscious years, I identified Jim as an establishment figure of whom I did not approve, when, after the video of the late Sid Vicious performing Something Else on Top of the Pops, Savile warned the nation not to ride a motorbike without proper protection.

It turns out that he was the one who we should have been warned about. The BBC is under fire, from the usual anti-BBC quarters, for its part in “turning a blind eye” to what Savile seems to have been doing on their premises, in dressing rooms at Television Centre when Jim’ll was the king of early evening BBC. No chatter about how different our attitudes to paedophilia were then, in the 60s and 70s, can lessen the gruesome impact of what we’re now learning. This does not mean anybody covered it up. Savile was a superstar in the 60s and 70s, his creepiness all part of the eccentric nature of his persona – which, if later documentaries about him, particularly Louis Theroux’s, present a realistic picture, were extensions of his actual character. He did an awful lot of work for charity, and this seems to have been his cloak of protection. It’s entirely possible that people he worked with simply couldn’t believe he’d put his hands where they weren’t wanted.

I never met him. But when I first worked at the BBC, in the early 90s, I heard “rumours” about him that were pretty ugly. Funnily enough – or not very funnily enough – the rumours I heard were different from the ones that are now coalescing into testimony and possibly fact. I wouldn’t say they’re worse, but they are equally repellent on an entirely different level. They don’t involve under-age girls. When people say it was “an open secret” that he was a bit of a pervert, this incriminates anyone who heard the whispers. The entertainment industry has its own folklore of dirty stories about well-loved celebrities; with the way the tabloids have worked for the last few decades, you do sort of think: well, if they’re true, they’d have come out by now, surely? I never heard the stories about Savile’s penchant for under-age girls.

If you can assassinate a dead man, that’s what happening right now. Savile’s legend has been rewritten. Those who always found him creepy – which is most of us – can now congratulate ourselves for having spotted that he was a wrong’un, and yet, how brilliant are we for doing that after hearing first-hand accounts of his wrongdoing? It’s interesting that Kenny Everett, another much-loved and wacky Radio 1 and Top Of The Pops DJ, has been celebrated this week, and depicted as a man haunted by the “shame” of his own homosexuality, although I assume that in liberal corners of entertainment, this was not condemned, but accepted. Concerning this “open secret”, we posthumously sympathise with and applaud Ken for battling on, because it was he who was damaged by Victorian attitudes to a legal lifestyle choice. (I say “we” applaud him; I’m sure a lot of purple-faced, Mail-reading colonels in the home counties still think being gay is an affront to nature, but who cares about them.)

If Savile was a serial molester of children, then he deserves to have his plaque and his statue taken down, for he died without ever being found out or punished for ruining so many lives. We didn’t even use the term paedophilia back in the crazy 60s and 70s, although I vividly remember Public Information Films about not talking to “strangers” who promised to show you puppies. Pop star Alvin Stardust and footballer Kevin Keegan, however, approached kids and showed them how to cross the road correctly in similar films. The moral being: if someone famous comes up to you, it’s fine. If Jimmy Savile had come up to them, it would have been fine.

It’s awkward having to readjust your view of the world. I have been thoroughly enjoying BBC4’s repeats of Top Of The Pops from 1977 and, currently, 1978. They are fascinating social documents, when shown in full. Will they still show the editions hosted by Savile, with his mating yodel and his hands all over the 15-year-olds? I suspect not. Although they did show one with Gary Glitter on earlier this year.

A final thought: when I was about 12, the same age as the diary entry above when Jim’ll Fix It was a fixture and Willy Wonka considered a benevolent bachelor proffering sweets, I made a papier maché Jimmy Savile puppet in art at school. Oddly, I made a “horror” version of Jim, with blood coming out of his mouth and eyes, and an evil face. That’s what childhood is about: innocent fun. I’m glad he never answered my letter.

October 2, 2012

Holy split!

[image error]

Not having time to review it here in full, two weeks ago I Tweeted about the hugely talented Australian director Andrew Dominick’s hyped hitmen caper Killing Them Softly, saying something pithy and eye-catching like, “Beware the four- and five-star reviews,” keen to posit a sincere counterbalance to the hype with a limb-balanced view that, beyond some smart dialogue, moodily derelict visuals and a nuanced turn by Brad Pitt, this is a fairly modest film that’s short and narratively underpowered, and perhaps not the dazzling, politically-charged Tarantino-esque epic-for-our-times it was being marketed as. You know, it’s a decent three-star movie. In my book. Which is the only book I’m writing.

At the end of the day, it’s just my opinion versus the opinions of most other critics, but I felt that anyone yet to pay good money to see it might, in fact, appreciate an alternative view. I was disappointed that it’s all over so fast, that so little actually happens, and that there isn’t much in the way of resolution. For all the newsreel that places it firmly in the US presidential election year of 2008, its ending is pretty facile, when it might have been profound. (When the credits suddenly rolled, I genuinely thought, “Is that it?”)

The reason I’m telling you this, is that one respondent on Twitter called me “conceited” for expressing my opinion. This seemed harsh. We are all entitled to an opinion, and everyone is a critic, albeit not necessarily a professional one. Since I had paid money to see Killing Them Softly at a cinema, as is my preference, I was not commenting as a critic, but as a punter. Nobody’s opinion is more important than anybody else’s, but to express your own is not conceited.

I am about to offer my opinion on another film that has picked up rave reviews from critics, Holy Motors. Peter Bradshaw, who I respect and like (and who gave Killing Them Softly five stars in the Guardian), gave Holy Motors five stars in the Guardian; Robbie Collin gave it five in the Telegraph; Nick de Semlyen gave it five in Empire, so that’s a broad waterfront. Now, it is a strange, oblique, difficult, experimental film, and was always going to divide opinion. My opinion is that it is preening, self-congrulatory rubbish. You may disagree with me.

I have no history with its writer-director Leos Carax, although I am aware that his Les Amants du Pont-Neuf was an artistic hit and commercial flop in the early 90s (“the French Heaven’s Gate“), and it nearly bankrupted him. (He has only made five features in just over 30 years, which lends his work a Malick-like cachet that it may, or may not, deserve. I don’t know.) I was all too aware that Holy Motors was a big splash at Cannes this year, and that it had Kylie Minogue in it, which – it being an art movie – seemed newsworthy.

Well, it does have Kylie in it. But it’s not vital that it does, other than she looks a bit like Jean Seberg with her Jean Seberg haircut, in the brief segment that she is in, and it seems that more than anything else Holy Motors is like a European Cinema exam. Those who have swooningly submitted to its admittedly colourful and stylish but unhinged charms seem to delight in its constant references to such giants of French cinema as Cocteau, Renoir, Buñuel, Godard and, most evidently, Leos Carax. I’m not enough of a scholar in any of these great auteurs to spot every nod and wink, but I get the picture. It’s a film about cinema, which also tips its hat to Chaplin, and Chaney … and to Georges Franju’s key 1960 horror film Les yeux sans visage (Eyes Without A Face), in which Edith Scob wore an eerie facemask, and who, 50 years on, wears one in Holy Motors to make the debt as subtle as a big flashing neon sign.

I’m not against cinematic indulgence, or reflexivity, or in-jokes for cinephiles, although there can be something dryly academic about this kind of point-scoring. Not always: think of Pedro Almodóvar’s own playful update of Les yeux sans visage in La Piel que Habito (The Skin I Live In). It’s just that, well, I found the style, and the central performance by Carax muse Denis Lavant, irksome in the extreme. It’s not that I’m not clever enough to “get it”, just that I couldn’t get into it. It made me fidget. It frustrated me. Its undoubted audacity wasn’t enough.

There are amazing visual moments, such as the bit where Lavant’s mysterious, limo-bound master of disguise leads a brass band through a church, or when he dons a motion-capture bodysuit and performs an erotic tango with a lady, their movements transformed before our eyes into an alien animation; even some of the bits I hated, like Lavant’s transformation into the grunting “Monsieur Merde” who kidnaps Eva Mendes’ supermodel and shows her his erect penis in the sewer like a priapic Phantom of the Opera, had evocative visual merit. But I didn’t feel these added up to much.

There’s a journey, physically, and a series of episodes, that sort of join up to each other, but I felt as exhausted as Lavant’s latex-weathered clown by the end of the day and night over which the action takes place. And I won’t mention the humorous ending. Even people who are captivated by Holy Motors think the ending is a bit shit. It’s certainly an evocative spin around Paris, mostly by car, occasionally on foot, but the imagery seemed fashioned by blunt instrument, and unless you are a member of Carax’s club, you weren’t really welcomed with open arms.

That’s my opinion. It is an opinion that is mine. And what it is, too.

And yes, I know Buñuel was Spanish, but he had two French periods.

October 1, 2012

Don’t speak!

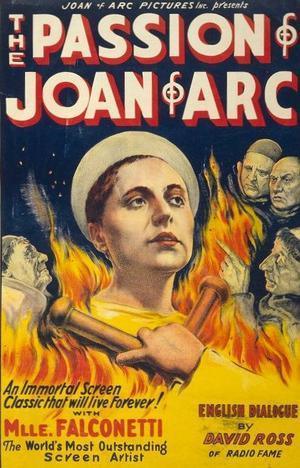

I was almost speechless after this rare cinematic treat at the weekend. We had tickets to see Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 silent classic La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc – or Jeanne d’Arc lidelse og død – on the big screen at the BFI Southbank in London, with live musical accompaniment and the original Danish intertitles to add to the authentic evocation of the 1920s experience. Not everyone’s idea of a big Saturday night out in the year 2012, I realise, although the auditorium at NFT1 was encouragingly packed.

This was showing as part of the BFI’s Sight & Sound Poll Winners season, as it was voted number 9 in the magazine’s most recent ten-year critics’ poll, as discussed here. Because it’s silent, and foreign, and black and white, it’s pushing against many prejudices to find a modern audience, but I’m lucky enough to have grown up at a time when silents – early Mack Sennett and Hal Roach comedies at any rate – were still shown on TV during the school holidays, so even though these curios were already 50 years old, I was exposed to them without prejudice.

That said, it’s unusual to be sat in a cinema watching one. I am coming relatively late to Dreyer (I’m never shy to admit my own latecomings – nothing worse than someone pretending to have seen something they haven’t), but was knocked out by Ordet, earlier this year, one of his later, sound films. My appreciation of his work has also been coloured by my growing love of modern Scandinavian cinema and TV, the ground laid by a longer-held love of Ingmar Bergman. Put it this way, I’m as used to hearing Danish speech these days as I am to hearing, say, French, or Spanish, or Italian, and that wasn’t always the case. Oddly, there is no Danish speech in Joan of Arc, as it’s a French film of a French story, featuring French actors, speaking in French. But with the intertitles in Danish, it retains the director’s origins. (The BFI notes state that this restoration is the closest yet to a replica of what the audience at the 1928 premiere in Copenhagen would have seen. Imagine!)

I wish I could credit the amazing pianist, but it wasn’t Neil Brand as listed in the BFI notes, as he was introduced as Steve something, and I can’t remember his surname. He also played flute while tickling the ivories at certain points, and made dramatic percussive noises on the piano strings too. Bravo! There is something uniquely thrilling about watching moving images soundtracked before your very ears. (I once saw Raymond Briggs’ The Snowman at the Cadogan Hall with a live orchestra and choir, and that was brought to life, in a completely different way.) La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc is an hypnotic experience; you’re watching predominantly close-ups of actors’ faces for most of the 96 minutes, arranged as if in monochrome Expressionist paintings.

It goes without saying that the actors in these early silent movies will have been stage-trained. And the demands of emoting onstage, at a distance from the audience, mean that silent movies often feel melodramatic, with actors over-emoting, and over-gesturing. As such, they can be an acquired taste. In silent movies, damsels in distress will often hold a fist up to their mouth and bite their knuckles, to convey fear and anxiety. There’s a lot of staring off camera, too. But Jeanne d’Arc is incredibly controlled, and restrained, and subtle. Renée Jeanne Falconetti, as the Maid of Orleans, is seen throughout, her amazing face filling the screen, usually at the same diagonal angle as the iconic image of Christ, but with tears streaming down her cheeks. Actually 35 at the time, although playing a 19-year-old, she reminded me of the Cocteau Twins’ Elizabeth Fraser, with her shorn hair and wide eyes.

The judges are grotesques; again, characterful old stage actors, one imagines, shot at Expressionistic angles, and, once again, filling the screen. (The famous playwright Antonin Artaud, he of the Theatre Of Cruelty, is also seen, as a monk.) The contrast between Falconetti’s smooth, wet skin and theirs – dry, wrinkled, fat, puffy – is stark. There is no doubt who’s the goodie, and who are the baddies in this film. The story concerns only her trial, and is based upon actual 15th century court documentation (which is shown at the beginning), and falls into three acts: the charges against her; the torture; and her execution at the stake. We all know the outcome, but – as with Mel Gibson’s heavy-handed, blood-soaked Passion Of The Christ – we are forced to endure the prologue to death right there with the accused. It’s powerful stuff.

Loaded with symbolism – much of it, to be fair, also sometimes heavy-handed – this is a sensory experience that pushes a lot of buttons. You’re swept along by the music: torrid, melancholy, sparing; by the imploring images: ugly, beautiful, exquisitely framed, the early tableaux giving way in the last act to crowd scenes and mayhem that you’re just not expecting; and by the sheer inevitability of the tragedy, postponed by administrative and legislative to-ing and fro-ing in the courtroom.

Sometimes, you watch a “classic” (or “an immortal screen classic”, as per the original poster), and you appreciate its historical importance, and are glad that you have seen it, but it’s a dry, academic, box-ticking exercise. With Dreyer, for me, it’s an experience to savour. There’s nothing antique about this film. It’s over 80 years old, and yet it moves and terrifies and manipulates with the same skill and artistic audacity as anything powered by digital technology or studio profligacy or – and here’s the point – endless dialogue.

More of this type of thing, please.

Mind you, can’t wait to see Looper.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers